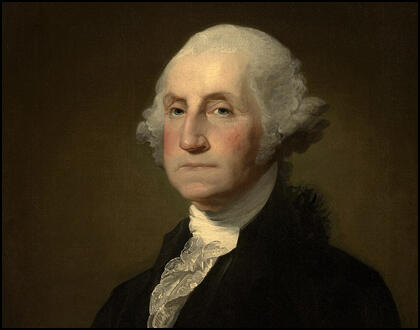

On this day on 22nd February

On this day in 1732 George Washington was born in Bridges Creek, Westmoreland County. After the death of his father, Augustine Washington, George went the live with his eldest half-brother, Lawrence.

Washington became a land surveying and in 1748 he found work with Lord Fairfax. After the death of Lawrence in 1752 Washington inherited the Mount Vernon estate. He also joined the local militia where he was involved in trying to keep the French out of the Ohio Valley. Washington was a highly successful soldier and by 1754 had been promoted to the rank of lieutenant-colonel.

In 1759 Washington married a rich young widow, Martha Custis. Washington now became one of the richest men in the country. This gave him the time to become involved in politics and was elected to the Virginia house of burgesses. He was also a member of the First and Second Continental Congresses in 1774 and 1775.

On 15th June, 1775, Washington was chosen as the Commander-in-Chief of the colonial army. Under his leadership the Americans were able to force the British Army out of Boston. He also inflicted defeats on the British at Trenton and Princeton. France entered the war on the American side in 1778 and Washington's army achieved the defeat and surrender of General Charles Cornwallis in Yorktown in 1781 which virtually brought an end to the American War of Independence.

Washington resigned his commission on 23rd December, 1783 and retired to his estate at Mount Vernon. He continued to be involved in politics and in 1787 presided over the convention of delegates from 12 states which formulated the American constitution. Washington was unanimously elected as the first President of the United States and was inaugurated on 30th April, 1789, in New York City. In government Washington worked closely with Thomas Jefferson (Secretary of State) and Alexander Hamilton (Treasury Secretary).

Washington was unanimously reelected in 1792 but by this time the government was not so united and there were serious disagreements between Jefferson's Democratic Republicans and Hamilton's Federalists. Washington tended to favour the Federalists and with the Democratic Republicans gaining increasing support, he decided not to seek a third term and retired from office on 3rd March, 1797.

George Washington was appointed as commander of the United States Army and served in this post until his death on 14th December, 1799.

On this day in 1735 Charles Lennox, the son of the Duke of Richmond, was born on 22nd February, 1735. After an education at Westminster School and entered the British army. Lennox served in several expeditions and distinguished himself in the Battle of Minden. He had reached the rank of colonel when he succeeded his father as the third Duke of Richmond on 6th August, 1750.He first took his seat in the House of Lords on 15th March 1756.

In 1760 the Duke of Richmond was was appointed a lord of the bedchamber, but shortly afterwards quarreled with George III and resigned from office. Richmond became lord-lieutenant of Sussex and in 1766 was appointed by the Marquis of Rockingham as Secretary of State for the Southern Department. Richmond retired from office when the Earl of Chatham replaced Rockingham as Prime Minister.

Richmond was a strong critic of Lord North's American policy. In December 1775, he declared in the House of Lords that the resistance of the colonists was "neither treason nor rebellion, but it is perfectly justifiable in every possible political and moral sense." It was during a speech made by Richmond in the House of Lords calling for the withdrawal of British troops from America that the Earl of Chatham collapsed and died.

Richmond also joined the campaign to remove the causes of Irish discontent. He opposed the Tory policy of an Act of Union and argued that he was in favour of an "union but not an union of legislature, but an union of hearts, hands, of affections and interests". Richmond retained his hostility to George III and in December 1779 he called for a reduction in the spending on the monarchy and described the civil list as "lavish and wasteful to a shameful degree".

In 1774 Richmond read a pamphlet that his friend, Granville Sharp, had written, called The Natural Right of People to Share in the Legislature (1774). This created an interest in parliamentary reform, and over the next few years Richmond read several pamphlets on the subject including The Nature of Civil Liberty (1776) by Richard Price and Take Your Choice (1777) by Major John Cartwright.

By the end of the 1770s most Whigs supported parliamentary reform. This included John Wilkes and Charles Fox. However, by this time, Richmond was the most radical in his party, supporting both annual parliaments and manhood suffrage. Richmond was now convinced that without parliamentary reform, revolution was inevitable.

On the 3rd June 1780 the Duke of Richmond decided to push the Whigs into action by introducing his own proposals for the reform of Parliament. His bill included plans for annual parliaments, manhood suffrage and 558 equally populous electoral districts. Richmond found very little support for his radical proposals and his bill was rejected without a vote.

The Marquis of Rockingham, the leader of the Whigs, died on 1st July 1782. Richmond attempted to become leader of the party, but his radical views on parliamentary reform ensured that he was defeated by the Duke of Portland. In April 1783 William Pitt invited Richmond to join his coalition ministry. He initially refused, but Richmond eventually joined the government and after that date showed little interest in the subject of parliamentary reform.

In 1794 Thomas Hardy and John Horne Tooke of the London Corresponding Society, were charged with high treason. Hardy and Tooke argued that were not guilty of treason as the Corresponding Society had been constituted solely to carry out the reforms proposed by the Duke of Richmond's Reform Bill of 1780. Richmond was called upon to testify at their trial where he was forced to admit that in 1780 he had supported the same measures that had resulted in Hardy and Tooke being charged with high treason. Richmond was severely embarrassed by having to publicly acknowledge the radical views he had held before becoming a member of the government. Tooke and Hardy were acquitted and two months later the Duke of Richmond was sacked from the cabinet.

This brought an end to the Richmond's involvement in government. He retired to Goodwood where he supervised the planning and construction of a race track near his home. From 1796 to 1800 Richmond only appeared in the House of Lords on two occasions. The Duke of Richmond spoke for the last time in the House of Lords on 25th June 1804. He died at Goodwood, Sussex, on 29th December, 1806 and afterwards was buried in Chichester Cathedral.

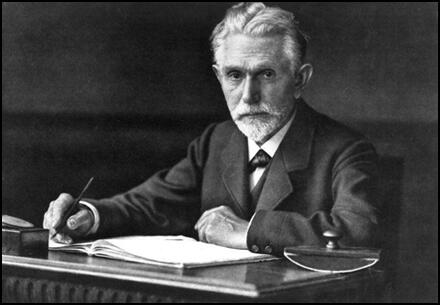

On this day in August Bebel, the son of a noncommissioned officer in the Prussian Army was born in Deutz on 22nd February, 1840. He later recalled: "The family of a Prussian petty-officer in those days lived in very penurious circumstances. The salary was more than scanty, and altogether the military and official world of Prussia lived poorly at that time.... My mother obtained permission to keep a sort of a canteen, in other words, she had license to sell sundry articles of daily use to the garrison. This was done in the only room at our disposal. I can still see mother before me as she stood in the light of a lamp fed by rape-oil and filled the earthen bowls of the soldiers with steaming potatoes in their jackets, at the rate of 6 Prussian pennies per bowl."

After leaving school he worked as a carpenter in Leipzig, Salzburg and Tyrol. In 1859 he attempted to join the army but was rejected as being physically unfit. Bebel became interested in politics and took part in trade union activities. He became a socialist after reading the work of Ferdinand Lassalle, which popularized the ideas of Karl Marx.

Bebel distributed copies of Lassalle's pamphlets to fellow workers. He admitted in his autobiography, Reminiscences (1911): "The open letter of Lassalle did not make at all such apt impression upon the world of labor as had been expected, in the first place, by Lassalle himself; in the second place, by the small circle of his followers. For my part, I distributed about two dozen copies in the Industrial Educational Club, in order to give the other side a chance. That the letter should have made so little impression upon the majority of the laborers in the movement of that time, may seem inexplicable today to some people. But it was quite natural. Not merely the economic, but also the political conditions were still very backward. Professional freedom, free migration, liberty to settle down, exemption from passports, liberty to wander, freedom of association and assembly, such were the demands that appealed more closely to the laborer of that time than productive associations subsidized by the state, of which he had no clear conception."

A group of trade unionists that became known collectively as the "junta" urged the establishment of an international organisation. This included Robert Applegarth, William Allan, George Odger and Johann Eccarius. "The aim of the Junta was to satisfy the new demands which were being voiced by the workers as an outcome of the economic crisis and the strike movement. They hoped to broaden the narrow outlook of British trade unionism, and to induce the unions to participate in the political struggle".

On September 28, 1864, an international meeting for the reception of the French delegates took place in St. Martin’s Hall in London. The meeting was organised by George Howell and attended by a wide array of radicals, including August Bebel, Karl Marx, Friedrich Engels, Élisée Reclus, Ferdinand Lassalle, William Greene, Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, Friedrich Sorge and Louis Auguste Blanqui. The historian Edward Spencer Beesly was in the chair and he advocated "a union of the workers of the world for the realisation of justice on earth".

In his speech, Beesly "pilloried the violent proceedings of the governments and referred to their flagrant breaches of international law. As an internationalist he showed the same energy in denouncing the crimes of all the governments, Russian, French, and British, alike. He summoned the workers to the struggle against the prejudices of patriotism, and advocated a union of the toilers of all lands for the realisation of justice on earth."

The new organisation was called the International Workingmen's Association. Karl Marx was asked to become a member of the General Council that consisted of two Germans, two Italians, three Frenchmen and twenty-seven Englishmen (eleven of them from the building trade). Marx was proposed as President but as he later explained: "I declared that under no circumstances could I accept such a thing, and proposed Odger in my turn, who was then in fact re-elected, although some people voted for me despite my declaration."

In 1865 he met Wilhelm Liebknecht. Bebel later recalled: "Liebknecht’s genuine fighter’s nature was keyed up by an impregnable optimism, without which no great aim can be accomplished. No blow that struck him, personally or the party, could rob him for a minute of his courage or of his composure. Nothing took him unawares; he always knew a way out. Against the attacks of his antagonists his watchword was: Meet one rascal by one and a half. He was harsh and ruthless against our opponents, but always a good comrade to his friends and associates, ever trying to smooth over existing difficulties."

Over the next few years the worked together in an effort to spread the ideas of Karl Marx. In 1868 he won a seat in the Reichstag. The following year Bebel and Liebknecht formed the Social Democratic Workers' Party of Germany (SDAP) together. Bebel and Liebknecht also established a newspaper, Der Volksstaat. In 1870 the two men used the newspaper to promote the idea that Otto von Bismarck had provoked France into war and called on workers from both countries to unite in overthrowing the ruling class. As a result, Bebel and Liebknecht were arrested and charged with high treason. In 1872, both men were convicted and sentenced to two years in the Königstein Fortress.

On his release in 1874 Bebel was elected to the Reichstag. The following year he helped the SDAP merge with the General German Workers' Association (ADAV), an organisation led by Ferdinand Lassalle, to form the Social Democratic Party (SDP). In the 1877 General Election in Germany the SDP won 12 seats. This worried Otto von Bismarck, and in 1878 he introduced an anti-socialist law which banned Social Democratic Party meetings and publications.

In 1879 August Bebel published Woman and Socialism. In the book Bebel argued that it was the goal of socialists "not only to achieve equality of men and women under the present social order, which constitutes the sole aim of the bourgeois women's movement, but to go far beyond this and to remove all barriers that make one human being dependent upon another, which includes the dependence of one sex upon another."

The book had a tremendous influence on fellow members of the Social Democratic Party. This included Karl Schmidt who gave it to his daughter, Käthe Kollwitz to read. She was particularly impressed with one passage of the book that stated: "In the new society women will be entirely independent, both socially and economically... The development of our social life demands the release of woman from her narrow sphere of domestic life, and her full participation in public life and the missions of civilisation." Bebel also predicted the dissolution of marriage, believing that socialism would free women from their second-class status.

After the anti-socialist law ceased to operate in 1890, the SDP grew rapidly. However, Bebel had problems with divisions in the party. Eduard Bernstein, a member of the SDP, who had been living in London, became convinced that the best way to obtain socialism in an industrialized country was through trade union activity and parliamentary politics. He published a series of articles where he argued that the predictions made by Karl Marx about the development of capitalism had not come true. He pointed out that the real wages of workers had risen and the polarization of classes between an oppressed proletariat and capitalist, had not materialized. Nor had capital become concentrated in fewer hands. Bernstein's revisionist views appeared in his extremely influential book Evolutionary Socialism (1899). His analysis of modern capitalism undermined the claims that Marxism was a science and upset leading revolutionaries such as Vladimir Lenin and Leon Trotsky.

In 1901 Bernstein returned to Germany. This brought him into conflict with left-wing of the Social Democrat Party that rejected his revisionist views on how socialism could be achieved. This included those like Bebel, Karl Kautsky, Clara Zetkin, Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg, who still believed that a Marxist revolution was still possible.

During the 1905 Revolution Luxemburg and Leo Jogiches returned to Warsaw where they were soon arrested. Luxemburg's experiences during the failed revolution changed her views on international politics. Until then, Luxemburgbelieved that a socialist revolution was most likely to take place in an advanced industrialized country such as Germany or France. She now argued it could happen in an underdeveloped country like Russia.

At the Social Democratic Party Congress in September 1905, Rosa Luxemburg called for party members to be inspired by the attempted revolution in Russia. "Previous revolutions, especially the one in 1848, have shown that in revolutionary situations it is not the masses who have to be held in check, but the parliamentarians and lawyers, so that they do not betray the masses and the revolution." She then went onto quote from The Communist Manifesto: "The workers have nothing to lose but their chains; they had a world to win."

Bebel did not share Luxemburg's views that now was the right time for revolution. He later recalled: "Listening to all that, I could not help glancing a couple of times at the toes of my boots to see if they weren't already wading in blood." However, he preferred Luxemburg to Eduard Bernstein and he appointed her to the editorial board of the SPD newspaper, Vorwarts (Forward). In a letter to Leo Jogiches she wrote: "The editorial board will consist of mediocre writers, but at least they'll be kosher... Now the Leftists have got to show that they are capable of governing."

In 1906 Rosa Luxemburg published her thoughts on revolution in The Mass Strike, the Political Party and the Trade Unions. She argued that a general strike had the power to radicalize the workers and bring about a socialist revolution. "The mass strike is the first natural, impulsive form of every great revolutionary struggle of the proletariat and the more highly developed the antagonism is between capital and labour, the more effective and decisive must mass strikes become. The chief form of previous bourgeois revolutions, the fight at the barricades, the open conflict with the armed power of the state, is in the revolution today only the culminating point, only a moment on the process of the proletarian mass struggle."

These views were not well received by Bebel and other party leaders. Luxemburg wrote to Clara Zetkin: "The situation is simply this: August Bebel, and still more so the others, have completely spent themselves on behalf of parliamentarism and in parliamentary struggles. Whenever anything happens which transcends the limits of parliamentarism, they are completely hopeless - no, even worse than that, they try their best to force everything back into the parliamentary mould, and they will furiously attack as an enemy of the people anyone who wants to go beyond these limits."

Despite these conflicts between the left, headed by Rosa Luxemburg, and right led by Eduard Bernstein, the S won 110 seats in the Reichstag in the election of 1912. The Social Democratic Party (SDP) was now the largest political party in Germany.

August Bebel died following a heart attack on 13th August, 1913 during a visit to a sanatorium in Graubünden, Switzerland. He was 73 years old at the time of his death. His body was buried in Zürich.

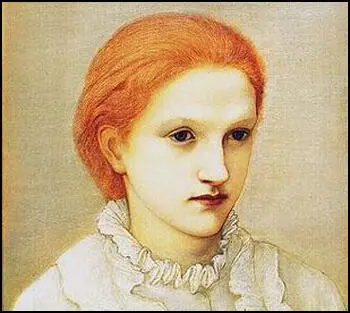

On this day in 1858 Frances Balfour, the daughter of George Douglas Campbell, eighth duke of Argyll (1823–1900), was born . The tenth of twelve children, Frances had a hip-joint disease and from early childhood was constantly in pain and walked with a limp.

Her biographer, Joan B. Huffman, has pointed out: " Her formal education was provided by an English governess. However, the main method by which she learned throughout her life was by listening to and participating in the conversations, particularly at the dinner table, of her parents, in-laws, and male acquaintances, especially ministers and politicians, whose company and friendship she preferred."

The Duke and Duchess of Argyll were both supporters the Liberal Party in Parliament and were involved in several different campaigns for social reform. Frances also helped with these campaigns as a child and one way she contributed was to knit garments to be sent to the children of ex-slaves.

Frances married Eustace Balfour in 1879. At first the Duke of Argyll had opposed the relationship because he came from a well-known Tory family. Eustace's uncle, the Marquis of Salisbury, had three spells as Prime Minister. Eustace's elder brother, Arthur Balfour, was also a Conservative politician and was later to become Britain's Prime Minister (1902-1905). Unlike his brother and uncle, Eustace did not take an active role in politics. However, he shared his family's Tory views and this caused conflict between him and his wife. Frances was a passionate Liberal and was a loyal supporter of William Gladstone and his government. The couple never overcame these political differences and spent less and less time together. Eustace was a heavy drinker and eventually became an alcoholic. Eustace died in 1911.

Membership of the Women's Liberal Unionist Association brought her into contact with feminists such as Marie Corbett and Eva Maclaren. In 1887 Balfour joined with Corbett and Maclaren in the recently formed Liberal Women's Suffrage Society. Frances Balfour wrote in her journal: "I don't remember any date, in which I was not a passive believer in the rights of women to be recognised as full citizens in this country. No one ever spoke to me on the subject except as shocking or ridiculous, more often as an idea that was wicked, immodest and unwomanly."

Her biographer, Joan B. Huffman has argued: "Lady Frances began her political work when she joined the campaign to secure the enfranchisement of British women. Indeed, she was one of the highest ranking members of the aristocracy to assume a leadership role in the women's suffrage movement. One of the few women of her class to agitate for votes for women from the 1880s onwards, she became a leader of the constitutional suffragists. Her feminism, like much of the rest of her political philosophy, derived from her personal experiences. In her youth and adolescence she heard the arguments against slavery advanced by members of her family (her mother and grandmother, Harriet, duchess of Sutherland, were ardent abolitionists). As a young woman she was thwarted in her desire to become a nurse and frustrated because she could observe, but not aspire to a seat in, parliament. Thus, as a feminist, Lady Frances espoused equal rights for women and was absolutely convinced that women should be permitted to study and train for careers in all the professions on the same terms as men."

In 1896 Frances Balfour became president of the Central Society for Women's Suffrage. A position she was to hold for the next eighteen years. She was a good speaker and often appeared at suffragist public meetings. She was also well-placed to try and influence leading members of the House of Commons. Frances and her sister-in-law, Betty Balfour, tried hard to persuade Arthur Balfour, to support women's suffrage. Although Balfour accepted the justice of women's rights, his lack of enthusiasm meant that he was unwilling to fight for the cause inside the largely unsympathetic Conservative Party.

Balfour was a completely non-violent suffragist and was totally opposed to the militant actions of the Women's Political and Social Union (WSPU). Francis disagreed with her sister-in-law, Constance Lytton, who joined the WSPU and had to endure several periods of imprisonment. Frances was also opposed to socialism and was very unhappy with the decision of the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies in 1912 to support the Labour Party.

After women were granted the vote, Balfour spent her time writing books and articles. This included five biographies: Lady Victoria Campbell (1911), The Life and Letters of the Reverend James MacGregor (1912), Dr Elsie Inglis (1918), The Life of George, Fourth Earl of Aberdeen (1923), and A Memoir of Lord Balfour of Burleigh (1925) and an autobiography, Me Obliviscaris (1930), where she recalled: "My gifts, such as they were, lay in being a sort of liaison officer between Suffrage and the Houses of Parliament, and being possessed of a good platform voice.

Lady Frances Balfour died at her London home, 32 Addison Road, Kensington, on 25th February 1931 from pneumonia and heart failure. She was buried at Whittingehame, the Balfour family home in East Lothian.

On this day in 1892 Edna St Vincent Millay was born in Rockland, Maine on 22nd February, 1892. Cora St Vincent Millay raised Edna and her three sisters on her own after her husband left the family home. When Edna was twenty her poem, Renascence , was published in The Lyric Year . A wealthy woman named Caroline B. Dow heard Millay reciting her poetry and offered to pay for Millay’s education at Vassar College.

In 1917, the year of her graduation, Millay published her first book, Renascence and Other Poems. After leaving Vassar she moved to Greenwich Village where she befriended writers such as Floyd Dell, John Reed and Max Eastman. The three men were all involved in the left-wing journal, The Masses, and she joined in their campaign against USA involvement in the First World War.

Millay also joined the Provincetown Theatre Group. A shack at the end of the fisherman's wharf at the seaport of Provincetown was turned into a theatre. Others who wrote or acted for the group included Floyd Dell, Eugene O'Neill, John Reed, George Gig Cook, Mary Heaton Vorse, Susan Glaspell, Hutchins Hapgood, Neith Boyce and Louise Bryant. Millay was considered a great success as Annabelle in Floyd Dell's The Angel Intrudes. In 1918 Millay directed and took the lead in her own play, The Princess Marries the Page. Later she directed her morality play, Two Slatterns and the King at Provincetown.

In 1920 Millay published a new volume of poems, A Few Figs from Thistles. This created considerable controversy as the poems dealt with issues such as female sexuality and feminism. Her next volume of poems, The Harp Weaver (1923), was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry. The writer, Dorothy Parker wrote: "Like everybody else was then, I was following in the footsteps of Edna St Vincent Millay, unhappily in my own horrible sneakers.... We were all being dashing and gallant, declaring that we weren't virgins, whether we were or not. Beautiful as she was, Miss Millay did a great deal of harm with her double-burning candles. She made poetry seem so easy that we could all do it. But, of course, we couldn't."

Floyd Dell recalls how he was attending a party at the home of Dudley Field Malone and Doris Stevens, when he saw Edna meet Eugen Boissevain, the widower of Inez Milholland: "We were all playing charades at Dudley Malone's and Doris Stevens's house. Edna Millay was just back from a year in Europe. Eugene and Edna had the part of two lovers in a delicious farcical invention, at once Rabelaisian and romantic. They acted their parts wonderfully-so remarkably, indeed, that it was apparent to us all that it wasn't just acting. We were having the unusual privilege of seeing a man and a girl fall in love with each other violently and in public, and telling each other so, and doing it very beautifully."

The couple married in 1923. They lived at a farmhouse they named Steepletop, near Austerlitz. Both were believers in free-love and it was agreed they should have an open marriage. Boissevain managed Millay's literary career and this included the highly popular readings of her work. In his autobiography, Homecoming (1933), Floyd Dell commented that he had "never heard poetry read so beautifully".

In 1927 she joined with other radicals such as John Dos Passos, Alice Hamilton, Paul Kellog, Jane Addams, Heywood Broun, William Patterson, Upton Sinclair, Dorothy Parker, Ben Shahn, Felix Frankfurter, John Howard Lawson, Freda Kirchway, Floyd Dell, Bertrand Russell, John Galsworthy, Arnold Bennett, George Bernard Shaw and H. G. Wells in the campaign against the proposed execution of Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti. The day before the execution Millay was arrested at a demonstration in Boston for "sauntering and loitering" and carrying the placard "If These Men Are Executed, Justice is Dead in Massachusetts".

Later Millay was to write several poems about the the Sacco-Vanzetti Case. The most famous of these was Justice Denied in Massachusetts . Her next volume of poems, The Buck and the Snow (1928) included several others including Hangman's Oak , The Anguish , Wine from These Grapes and To Those Without Pity . Floyd Dell, a long-term friend, said of her: "Edna St. Vincent Millay was a person of such many-sided charm that to know her was to have a tremendous enrichment of one's life, and new horizons... Edna Millay was to become a lover's poet. But with some of her poems she was also to give dignity and sweetness to those passionate friendships between girls in adolescence, where they stand terrified at the bogeys which haunt the realm of grown-up man-and-woman love, and turn back for a while to linger in the enchanted garden of childhood. She had a gift for friendship. People try to draw a distinction between friendship and love; but friendship had for her all the candor and fearlessness of love, as love had for her the gaiety and generosity of friendship."

In 1931 Millay published, Fatal Interview (1931) a volume of 52 sonnets in celebration of a recent love affair. Edmund Wilson claimed the book contained some of the greatest poems of the 20th century. Others were more critical preferring the more political material that had appeared in The Buck and the Snow.

In 1934 Arthur Ficke, asked Edna St. Vincent Millay to write down the "five requisites for the happiness of the human race". She replied: " A job - something at which you must work for a few hours every day; An assurance that you will have at least one meal a day for at least the next week; An opportunity to visit all the countries of the world, to acquaint yourself with the customs and their culture; Freedom in religion, or freedom from all religions, as you prefer; An assurance that no door is closed to you, - that you may climb as high as you can build your ladder."

Millay's next volume of poems, Wine From These Grapes (1934) included the remarkable Conscientious Objector , a poem that expressed her strong views on pacifism. Huntsman, What Quarry? (1939) also dealt with political issues such as the Spanish Civil War and the growth of fascism.

During the Second World War Millay abandoned her pacifists views and wrote patriotic poems such as Not to be Spattered by His Blood (1941), Murder at Lidice (1942) and Poem and Prayer for the volume entitled Invading Army (1944).

Eugen Boissevain died in Boston on 29th August, 1949 of lung cancer. Edna St Vincent Millay was found dead at the bottom of the stairs in Steepletop on 19th October 1950.

On this day in 1911 Frances Harper died. Frances was born in Baltimore on 24th September, 1825. Her mother died three years later and she was looked after by relatives. Frances was educated at a school run by her uncle, Rev. William Watkins until the age of thirteen when she found work as a seamstress.

Harper wrote poetry and her first volume of verse, Forest Leaves, was published in 1845. The book was extremely popular and over the next few years went through 20 editions.

In 1850 Harper obtained employment as a teacher in Columbus, Ohio, but in 1853 became a travelling lecturer for the American Anti-Slavery Society. She was also a strong supporter of prohibition and woman's suffrage. She often read her poetry at these public meetings, including the extremely popular Bury Me in a Free Land.

Other volumes of poetry published by Harper include Poems on Miscellaneous Subjects (1854), Moses: A Story of the Nile (1869) and Sketches of Southern Life (1872). Harper was a strong supporter of women's suffrage and was a member of the American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA).

Her first novel, Iloa Leroy, a story about a rescued black slave, appeared in 1892. This was followed by Minnie's Sacrifice, Sowing and Reaping and Trial and Triumph.

On this day in 1932 Edward (Ted) Kennedy, the youngest son of Joseph Patrick Kennedy and Rose Fitzgerald, was born in Brookline, Massachusetts. His great grandfather, Patrick Kennedy, had emigrated from Ireland in 1849 and his grandfathers, Patrick Joseph Kennedy and John Francis Fitzgerald, were important political figures in Boston.

Kennedy later admitted that as the youngest child he was treated with the utmost indulgence by his mother and sisters. He commented in later life that it was like "having a whole army of mothers around me."

Kennedy's father was a highly successful businessman and supporter of the Democratic Party. In 1937 Franklin D. Roosevelt appointed him as ambassador to Great Britain. Ted lived in London during this period and by the end of the Second World War when he was 13, he had attended 10 different schools. His eldest brother, Joseph Patrick Kennedy, was killed in action in France in 1944.

In 1950 Kennedy won a place at Harvard University. He was an outstanding sportsman but had difficulty with his academic studies. As one of his biographers has pointed out: "Faced with a Spanish examination he was sure he would fail, Kennedy paid a more adept friend to take it for him. To the chagrin of his family, the plot was discovered and he was expelled, though the incident was covered up for more than a decade. With his exemption from military service now void, he was conscripted into the army from 1951 to 1953. The family appeared to regard his brief service career as a form of punishment and made no effort to ease his lot."

After two years in the US Army Kennedy was allowed to return to Harvard. He got a BA in government in 1956 but failed to qualify for its law school and after a period at the Hague Academy of International Law he enrolled at the University of Virginia. While a student he married the former model, Joan Bennett in 1958.

A member of the Democratic Party Kennedy became involved in politics and in 1958 managed the Senate election campain of his brother, John Fitzgerald Kennedy. He graduated as a bachelor of law in 1959 and was admitted to the Massachusetts bar.

In 1960 Edward Kennedy helped his brother, Robert Kennedy, manage John Kennedy's successful presidential campaign against Richard Nixon. However, as John M. Broder pointed out in the New York Times: "In 1960, when John Kennedy ran for president, Edward was assigned a relatively minor role, rustling up votes in Western states that usually voted Republican. He was so enthusiastic about his task that he rode a bronco at a Montana rodeo and daringly took a ski jump at a winter sports tournament in Wisconsin to impress a crowd. The episodes were evidence of a reckless streak that repeatedly threatened his life and career."

In 1962 Kennedy entered the Senate as a representative of Massachusetts.When his brother was assassinated in 1963 he flew to the family home in Hyannis Port where he had the task of telling his father, Joseph Patrick Kennedy, now frail and bedridden, the news. As Evan Thomas has pointed out: "When the president was assassinated in November 1963, it fell to Teddy to tell their stroke-ridden father. His clumsy wording suggests the pain. There's been a bad accident, Ted began. The president has been hurt very badly. As a matter of fact, he died. Then the son dropped to his knees and wept into the outstretched hands of his father."

On 19th June, 1964, Edward Kennedy was a passenger in a private plane from Washington to Massachusetts that crashed into an apple orchard in bad weather, in the town of Southampton. The pilot and Edward Moss, one of Kennedy's aides, were killed. Kennedy suffered six spinal fractures and two broken ribs. He spent six months in hospital and suffered chronic back pain from the landing for the rest of his life.

Kennedy returned to the Senate in 1965 and along with Robert Kennedy he joined the campaign for the 1965 Voting Rights Act. He tried to strengthen it with an amendment that would have outlawed poll taxes. He lost by only four votes, and showed for the first time his committment to liberal causes.

Initially, Edward Kennedy gave his support to Lyndon B. Johnson when he expanded the U.S. role in the Vietnam War. However, he grew increasingly concerned about the large number of American deaths and after a trip to the country in January 1968 he argued that the president should tell South Vietnam, "Shape up or we're going to ship out." Later he called the war a “monstrous outrage.”

On 16th March, Robert Kennedy declared his candidacy for the presidency, stating, "I am today announcing my candidacy for the presidency of the United States. I do not run for the Presidency merely to oppose any man, but to propose new policies. I run because I am convinced that this country is on a perilous course and because I have such strong feelings about what must be done, and I feel that I'm obliged to do all I can." Edward Kennedy became his brother's leading campaigner.

Soon afterwards Lyndon B. Johnson withdrew from the contest and Robert Kennedy looked certain to be the party's candidate. He had just won his sixth primary in California when he was assassinated. Frank Mankiewicz said of seeing Edward at the hospital where Robert lay mortally wounded: "I have never, ever, nor do I expect ever, to see a face more in grief."

At his brother's funeral, Edward Kennedy gave a speech that included: "Few are willing to brave the disapproval of their fellows, the censure of their colleagues, the wrath of their society. Moral courage is a rarer commodity than bravery in battle or great intelligence. Yet it is the one essential, vital quality for those who seek to change a world that yields most painfully to change." He then went onto quote his brother: "Some men see things as they are and say why. I dream things that never were and say why not."

Edward Kennedy developed a drink problem after the death of Robert Kennedy. One of his biographers has pointed out: "The strain began to show on Kennedy, notably in his increased consumption of alcohol. It surfaced publicly when he went on a Senate fact-finding trip to Alaska the following spring. His staff and the accompanying journalists noticed him taking constant drags from a hip flask on the flights and then searching out bars at each stop. On the homeward flight he repeatedly teetered down the aisle, spilling his drinks on other passengers. He was also having difficulties with his marriage. Like his father and brother John, he had a voracious sexual appetite."

After Richard Nixon was elected in 1968 Edward Kennedy was widely assumed to be the front-runner for the 1972 Democratic nomination. In January 1969, Kennedy was elected as Senate Majority Whip, the youngest person to attain that position. In this role he made determined efforts to stop Nixon's plans to cut back on welfare and other federal programmes for the poor.

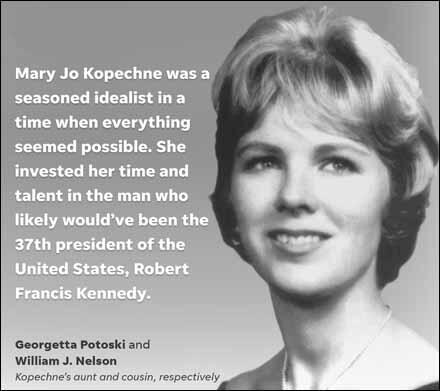

On 17th July, 1969, Mary Jo Kopechne joined several other women who had worked for the Kennedy family at the Edgartown Regatta. She stayed at the Katama Shores Motor Inn on the southern tip of Martha's Vineyard. The following day the women travelled across to Chappaquiddick Island. They were joined by Ted Kennedy and that night they held a party at Lawrence Cottage. At the party was Kennedy, Kopechne, Susan Tannenbaum, Maryellen Lyons, Ann Lyons, Rosemary Keough, Esther Newburgh, Joe Gargan, Paul Markham, Charles Tretter, Raymond La Rosa and John Crimmins.

Mary Jo Kopechne and Kennedy left the party at 11.15pm. Kennedy had offered to take Kopechne back to her hotel. He later explained what happened: "I was unfamiliar with the road and turned onto Dyke Road instead of bearing left on Main Street. After proceeding for approximately a half mile on Dyke Road I descended a hill and came upon a narrow bridge. The car went off the side of the bridge.... The car turned over and sank into the water and landed with the roof resting on the bottom. I attempted to open the door and window of the car but have no recollection of how I got out of the car. I came to the surface and then repeatedly dove down to the car in an attempt to see if the passenger was still in the car. I was unsuccessful in the attempt."

Instead of reporting the accident Edward Kennedy returned to the party. According to a statement issued by Kennedy on 25th July, 1969: "instead of looking directly for a telephone number after lying exhausted in the grass for an undetermined time, walked back to the cottage where the party was being held and requested the help of two friends, my cousin Joseph Gargan and Paul Markham, and directed them to return immediately to the scene with me - this was some time after midnight - in order to undertake a new effort to dive."

When this effort to rescue Mary Jo Kopechne ended in failure, Kennedy decided to return to his hotel. As the ferry had shut down for the night Kennedy, swam back to Edgartown. It was not until the following morning that Kennedy reported the accident to the police. By this time the police had found Mary Jo Kopechne's body in Kennedy's car.

Edward Kennedy was found guilty of leaving the scene of the accident and received a suspended two-month jail term and one-year driving ban. That night he appeared on television to explain what had happened. He explained: "My conduct and conversations during the next several hours to the extent that I can remember them make no sense to me at all. Although my doctors informed me that I suffered a cerebral concussion as well as shock, I do not seek to escape responsibility for my actions by placing the blame either on the physical, emotional trauma brought on by the accident or on anyone else. I regard as indefensible the fact that I did not report the accident to the police immediately."

At the inquest Judge James Boyle raised doubts about Kennedy's testimony. He pointed out that as Kennedy had a good knowledge of Chappaquiddick Island he could not understand how he managed to drive down Dyke Road by mistake. For example, on the day of the accident, Kennedy had twice had driven on Dyke Road to go to the beach for a swim. To get to Dyke Road involved a 90-degree turn off a metalled road onto the rough, bumpy dirt-track.

An investigation at the scene of the accident by Raymond R. McHenry, suggested that Kennedy approached the bridge at an estimated 34 miles (55 kilometres) per hour. At around 5 metres (17 feet) from the bridge, Kennedy braked violently. This locked the front wheels. According to McHenry: "The car skidded 5 metres (17 feet) along the road, 8 metres (25 feet) up the humpback bridge, jumped a 14 centimetre barrier, somersaulted through the air for about 10 metres (35 feet) into the water and landed upside-down."

Investigators found it difficult to understand why he was crossing Dyke Bridge when he said he was attempting to reach Edgartown which was in the opposite direction. They also could not understand why he was driving so fast on this unlit, uneven, road. They also could not work out how Kennedy escaped from the car. When it was recovered from the water all the doors were locked. Three of the windows were either open or smashed in. If Kennedy, a large-framed 6 foot 2 inches tall man could manage to get out of the car, why was it impossible for Kopechne, a slender 5 foot 2 inches tall, not do the same?

Local experts could not understand why Kennedy (and later, Markham and Gargan) could not rescue Kopechne from the car. It also surprised investigators that Kennedy did not seek help from Pierre Malm, who only lived 135 metres from the bridge. At the inquest Kennedy was unable to answer this question.

There were also doubts about the way Mary Jo Kopechne died. Dr. Donald Mills of Edgartown, wrote on the death certificate: "death by drowning". However, Gene Frieh, the undertaker, told reporters that death "was due to suffocation rather than drowning". John Farrar, the diver who removed Kopechne from the car, claimed she was "too buoyant to be full of water". It is assumed that she died from drowning, although her parents filed a petition preventing an autopsy.

Other questions were asked about Kennedy's decision to swim back to Edgartown. The 150 metre channel had strong currents and only the strongest of swimmers would have been able to make the journey safely. Also no one saw Kennedy arrive back at the Shiretown Inn in wet clothes. Ross Richards, who had a conversation with Kennedy the following morning at the hotel described him as casual and at ease.

Kennedy did not inform the police of the accident while he was at the hotel. Instead at 9am he joined Gargan and Markham on the ferry back to Chappaquiddick Island. Steve Ewing, the ferry operator, reported Kennedy in a jovial mood. It was only when Kennedy reached the island that he phoned the authorities about the accident that had taken place the previous night.

Dr. Robert Watt, Kennedy's family doctor, explained his patient's strange behaviour by claiming he was in a state of shock and confusion and "possible concussion."

President Richard Nixon told his White House chief of staff, H.R. Haldeman that this was "the end of Teddy" and that it "will be around his neck forever." Max Lerner wrote in Ted and the Kennedy Legend: A Study in Character and Destiny (1980), this self-inflicted wound, more than any other event, "blocked his path to the White House, called his credibility into question and damaged the Kennedy legend."

The Chappaquiddick incident continued to haunt Kennedy and in January 1971, he lost his position as Senate Majority Whip when he was defeated by Senator Robert Byrd, 31–24. Kennedy now concentrated on wider political issues. This included becoming chair of the Senate subcommittee on health care. Over the next few years Edward Kennedy developed a well-deserved reputation in Capitol Hill as a diligent and effective legislator.

As Evan Thomas pointed out in Newsweek: "Edward Kennedy, perhaps more than any United States senator in the past half century, cared about the poor and dispossessed. Though he was relentlessly mocked by the right as a tax-and-spend liberal, he kept the faith.... He was hardly the first rich person to care. Oblige has gone with noblesse for ages; Franklin Roosevelt, creator of the New Deal, was a rich aristocrat. But there was a seriousness, a doggedness, to Kennedy. He was no dilettante, no limousine liberal. He was a prodigious worker, the strongest force in the government for women's rights and health care, civil rights and immigration, the rights of the disabled and education. He was effective: in the Senate, to get something done, you went to Ted Kennedy."

Kennedy was also an outspoken critic of President Richard Nixon. He made several speeches attacking Nixon's policies in Vietnam. He called it "a policy of violence that means more and more war". Kennedy also strongly criticized the Nixon administration's support for Pakistan and its ignoring of "the brutal and systematic repression of East Bengal by the Pakistani army".

However, because of the death of Mary Jo Kopechne, Kennedy was not in a position to obtain the nomination to take on Nixon in the 1972 presidential election. As one commentator has pointed out: "The judge ruled that Kennedy was probably guilty of criminal conduct but made no move to indict him. This obvious manipulation of the local judiciary by the state's most powerful family was probably more damaging in the long term than the tragedy itself."

Edward Kennedy and Joan Bennett Kennedy had three children: Kara Anne (27th February, 1960), Edward Moore Kennedy, Jr. (26th September, 1961) and Patrick Joseph Kennedy (14th July, 1967). The children encountered several health problems. Patrick suffered from severe asthma attacks and in 1973 Edward was discovered to have bone cancer and had to have his right leg amputated. Joan has also had three miscarriages and this contributed to her developing a serious drink problem. In 1978, the couple separated and shortly afterwards she gave an interview to McCall's Magazine where she admitted to being an alcoholic.

In 1979 Kennedy made another attempt to become the Democratic Party presidential candidate when he took on the sitting president, Jimmy Carter, a member of his own party. Kennedy won 10 presidential primaries but he eventually withdrew from the race when it became clear that the public was still concerned about the events on Chappaquiddick Island. When he withdrew from the campaign he made a speech where he argued: "For me, a few hours ago, this campaign came to an end. For all those whose cares have been our concern, the work goes on, the cause endures, the hope still lives, and the dream shall never die."

Edward Kennedy and Joan Bennett Kennedy divorced in 1982. Kennedy easily defeated Republican businessman Ray Shamie to win re-election in 1982. He was already the ranking member of the Labor and Public Welfare Committee but Senate leaders also granted him a seat on the Armed Services Committee. Kennedy now became an outspoken critic of the foreign policy of President Ronald Reagan. This included intervention in the Salvadoran Civil War and the support for the Contras in Nicaragua.

Kennedy also objected to the support President Reagan gave to apartheid government in South Africa. In January 1985 he visited the country and spent a night in the Soweto home of Bishop Desmond Tutu and also visited Winnie Mandela, wife of imprisoned black leader Nelson Mandela. On his return to the United States he campaigned for economic sanctions against South Africa and was mainly responsible for the Comprehensive Anti-Apartheid Act of 1986. President Reagan attempted to veto the legislation but was overridden by the United States Congress (by the Senate 78 to 21, the House by 313 to 83). This was the first time in the 20th century that a president had a foreign policy veto overridden. Later that year he travelled to the Soviet Union where he had talks with Mikhail Gorbachev. This led to the release of several political prisoners, including Anatoly Shcharansky.

In 1991, Kennedy was involved in another scandal when his nephew William Kennedy Smith was accused of sexual offences against Patricia Bowman while at a party at the family's Palm Beach, Florida estate. Smith was eventually acquitted and even though he was not directly implicated in the case he issued a public statement about his life: " "I am painfully aware of the disappointment of friends and many others who rely on me to fight the good fight. I recognise my own shortcomings, the faults in the conduct of my private life."

Ted Kennedy met Victoria Reggie, a Washington lawyer at Keck, Mahin & Cate, on 17th June 1991. They were married on 3rd July, 1992, in a civil ceremony at Kennedy's home in McLean, Virginia.

Kennedy remained on the left of the party and has been identified with various progressive causes. He was achairman of the United States Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions. In 2007 he helped pass the Fair Minimum Wage Act, which incrementally raises the minimum wage by $2.10 to $7.25 over a two year period. The bill also included higher taxes for many $1 million-plus executives. Kennedy was quoted as saying, "Passing this wage hike represents a small, but necessary step to help lift America's working poor out of the ditches of poverty and onto the road toward economic prosperity."

On May 20, 2008, doctors announced that Kennedy has a malignant brain tumor, diagnosed after he experienced a seizure at Hyannisport. The following month Kennedy underwent brain surgery at Duke University Hospital.

During his last months Kennedy, who was chairman of the Senate health committee, used what energy he had left to try and get the proposal by Barack Obama, to extend insurance coverage to 46 million people. Kennedy described health reform as the "cause of my life". As The Washington Post pointed out: "His measures gave access to care for millions and funded treatment around the world. He was a longtime advocate for universal health care and promoted biomedical research, as well as AIDS research and treatment."

Edward Kennedy died on 26th August 2009. Nancy Pelosi, in a statement on Kennedy's death, vowed that a health reform bill would reach the statute book this year. "Ted Kennedy's dream of quality healthcare for all Americans will be made real this year because of his leadership and his inspiration." Marc R. Stanley, chairman of the National Jewish Democratic Council, said: "Kennedy dedicated much of his life to ensuring that affordable healthcare is available for all Americans. The greatest tribute that we can bestow is to thoughtfully, but urgently, enact comprehensive health insurance reform."

On this day in 1943 Sophie Scholl, Hans Scholl and Christoph Probst are executed for anti-Nazi activities.

On 13th January, 1943, the Gauleiter of Bavaria, Paul Giesler, addressed the students of University of Munich in the Main Auditorium of the Deutsche Museum. He argued that universities should not produce students with "twisted intellects" and "falsely clever minds". Giesler went on to state that "real life is transmitted to us only by Adolf Hitler, with his light, joyful and life-affirming teachings!" He went on to attack "well-bred daughters" who were shirking their war duties. Some women in the audience began calling out angry comments. He responded by arguing that "the natural place for a woman is not at the university, but with her family, at the side of her husband." The female students at the university should fulfill their duties as mothers instead of studying. He then added that "for those women students not pretty enough to catch a man, I'd be happy to lend them one of my adjutants".

Women students began shouting abuse at Giesler. He then ordered their arrest by his SS guards. Male students came to their aid and fights began all over the auditorium. Those who managed to escape ran out of the museum and after forming themselves in a large group, began marching in a procession in the direction of the university. They linked arms as they marched singing songs of solidarity. However, before they got to the university armed police forced them to disperse.

The White Rose group believed there was a direct connection between their leaflets and the student unrest. They decided therefore to print another 1,300 leaflets and to distribute them around the university. On 18th February, 1943, Sophie and Hans Scholl arrived at the University of Munich with a suitcase packed with leaflets. According to Inge Scholl: "They arrived at the university, and since the lecture rooms were to open in a few minutes, they quickly decided to deposit the leaflets in the corridors. Then they disposed of the remainder by letting the sheets fall from the top level of the staircase down into the entrance hall. Relieved, they were about to go, but a pair of eyes had spotted them. It was as if these eyes (they belonged to the building superintendent) had been detached from the being of their owner and turned into automatic spyglasses of the dictatorship. The doors of the building were immediately locked, and the fate of brother and sister was sealed."

Jakob Schmid, a member of the Nazi Party, saw them at the University of Munich, throwing leaflets from a window of the third floor into the courtyard below. He immediately told the Gestapo and they were both arrested. They were searched and the police found a handwritten draft of another leaflet. This they matched to a letter in Scholl's flat that had been signed by Christoph Probst. Following interrogation, they were all charged with treason.

Sophie, Hans and Christoph were not allowed to select a defence lawyer. Inge Scholl claimed that the lawyer assigned by the authorities "was little more than a helpless puppet". Sophie told him: "If my brother is sentenced to die, you musn't let them give me a lighter sentence, for I am exactly as guilty as he."

Sophie Scholl was interrogated all night long. She told her cell-mate, Else Gebel, that she denied her "complicity for a long time". But when she was told that the Gestapo had found evidence in her brother's room that proved she was guilty of drafting the leaflet. "Then the two of you knew that all was lost... We will take the blame for everything, so that no other person is put in danger." Sophie made a confession about her own activities but refused to give information about the rest of the group.

Friends of Hans and Sophie had immediately telephoned Robert Scholl with news of the arrests. Robert and Magdalena went to Gestapo headquarters but they were told they were not allowed to visit them in prison over the weekend. They were not told that there trial was to begin on the Monday morning. However, another friend, Otl Aicher, telephoned them with the news. They were met by Jugen Wittenstein at the railway station: "We have very little time. The People's Court is in session, and the hearing is already under way. We must prepare ourselves for the worst."

Sophie's parents tried to attend the trial and Magdalene told a guard: "I’m the mother of two of the accused." He responded: "You should have brought them up better." Robert Scholl was forced his way past the guards at the door and managed to get to his children's defence attorney. "Go to the president of the court and tell him that the father is here and he wants to defend his children!" He spoke to Judge Roland Freisler who responded by ordering the Scholl family from the court. The guards dragged them out but at the door Robert was able to shout: "There is a higher justice! They will go down in history!"

Later that day Sophie Scholl, Hans Scholl and Christoph Probst were all found guilty. Judge Freisler told the court: "The accused have by means of leaflets in a time of war called for the sabotage of the war effort and armaments and for the overthrow of the National Socialist way of life of our people, have propagated defeatist ideas, and have most vulgarly defamed the Führer, thereby giving aid to the enemy of the Reich and weakening the armed security of the nation. On this account they are to be punished by death. Their honour and rights as citizens are forfeited for all time."

Werner Scholl was in court in his German Army uniform. He managed to get to his brother and sister. "He shook hands with them, tears filling his eyes. Hans was able to reach out and touch him, saying quickly, Stay strong, no compromises."

Robert and Magdalena managed to see their children before they were executed. Their daughter, Inge Scholl, later explained what happened: "First Hans was brought out. He wore a prison uniform, he walked upright and briskly, and he allowed nothing in the circumstances to becloud his spirit. His face was thin and drawn, as if after a difficult struggle, but now it beamed radiantly. He bent lovingly over the barrier and took his parents' hands... Then Hans asked them to take his greetings to all his friends. When at the end he mentioned one further name, a tear ran down his face; he bent low so that no one would see. And then he went out, without the slightest show of fear, borne along by a profound inner strength."

Magdalena Scholl said to her 22 year-old daughter: "I'll never see you come through the door again." Sophie replied, "Oh mother, after all, it's only a few years' more life I'll miss." Sophie told her parents she and Hans were pleased and proud that they had betrayed no one, that they had taken all the responsibility on themselves.

Else Gebel shared Sophie Scholl's cell and recorded her last words before being taken away to be executed. "How can we expect righteousness to prevail when there is hardly anyone willing to give himself up individually to a righteous cause.... It is such a splendid sunny day, and I have to go. But how many have to die on the battlefield in these days, how many young, promising lives. What does my death matter if by our acts thousands are warned and alerted. Among the student body there will certainly be a revolt."

They were all beheaded by guillotine in Stadelheim Prison only a few hours after being found guilty. A prison guard later reported: "They bore themselves with marvelous bravery. The whole prison was impressed by them. That is why we risked bringing the three of them together once more-at the last moment before the execution. If our action had become known, the consequences for us would have been serious. We wanted to let them have a cigarette together before the end. It was just a few minutes that they had, but I believe that it meant a great deal to them."

On this day in 1951 women's rights campaigner, Ethel Snowden suffered a stroke and died at 28 Lingfield Road, Wimbledon.

Ethel Annakin was born on 8th September 1881 at Pannal, near Harrogate, the daughter of Richard Annakin, a nonconformist building contractor, and his wife, Hannah Hymas.

Ethel went to Edge Hill College in Liverpool, to train as a teacher, where a radical preacher, Rev. C. F. Aked, converted her to Christian Socialism. In 1903 she moved to Leeds to take up a post as a schoolteacher and became a member of the Independent Labour Party (ILP) she was also active in the Temperance Society. At the ILP she met Mary Gawthorpe and Isabella Ford, and the three women formed a local branch of the Nation Union of Women's Suffrage Societies.

In 1904 Ethel met Philip Snowden at a Fabian Society meeting in Leeds. The couple were married the following year at Otley Register Office. The guests included Isabella Ford and Fred Jowett. Snowden, who had not previously supported votes for women, was persuaded by his wife's arguments, and over the next few years played an active role in the women's suffrage campaign.

As her biographer, June Hannam, has pointed out: "After her marriage Ethel Snowden resigned from teaching to concentrate on helping her husband's political career. She also continued to carry out propaganda for socialism and feminism, although the suffrage campaign increasingly became her main concern." As a member of the executive committee of the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies Ethel Snowden lectured all over the country and also attended conferences in Europe organized by the International Women's Suffrage Alliance.

The Labour Leader described Ethel Snowden as a "second Annie Besant … to her good gifts of dark eyes, golden brown hair and rich colour, nature has added a sweet singing voice and musical ability of no mean order … she has won the affectionate regard of all those who have come into intimate acquaintance with her by her warm enthusiasm for the cause."

Philip Snowden, who had been trying to enter the House of Commons, was finally successful in the 1906 General Election when he was elected as the member for Blackburn. Over the next ten years, Snowden, who was a member of the Men's League For Women's Suffrage gave considerable support to the campaign for equal rights.

Ethel Snowden wrote several pamphlets on the subject of women where she advocated co-operative child-minding and state benefits for mothers. Snowden also wrote two important books on politics, The Woman Socialist (1907) and The Feminist Movement (1913). June Hannam has argued: "She (Snowden) argued that the state should assume major responsibility for the costs of childcare, including state salaries for mothers and advocated co-operative housekeeping and easier divorce. Influenced by the ideas of eugenicists she called for state control of marriage, believing that the mentally ill and those aged under twenty-six should not be able to marry."

Like her husband, Ethel was a pacifist and refused to support Britain's involvement in the First World War. They both joined the Union of Democratic Control (UDC). Other members included Arthur Ponsonby, J. A. Hobson, Charles Buxton, Frederick Pethick-Lawrence, Norman Angell, Arnold Rowntree, Philip Morrel, Morgan Philips Price, George Cadbury, Helena Swanwick, Fred Jowett, Ramsay MacDonald, Tom Johnston, Philip Snowden, Ethel Snowden, Arthur Henderson, David Kirkwood, William Anderson, Isabella Ford, H. H. Brailsford, Israel Zangwill, Bertrand Russell, Margaret Llewelyn Davies, Konni Zilliacus, Margaret Sackville, Olive Schreiner and Morgan Philips Price.

The Union of Democratic Control soon emerged at the most important of all the anti-war organizations in Britain and by 1915 had 300,000 members. Frederick Pethick-Lawrence explained the objectives of the UDC: "As its name implies, it was founded to insist that foreign policy should in future, equally with home policy, be subject to the popular will. The intention was that no commitments should be entered into without the peoples being fully informed and their approval obtained. By a natural transition, the objects of the Union came to include the formation of terms of a durable settlement, on the basis of which the war might be brought an an end."

In 1915 and Ethel Snowden became a member of the executive of the Women's International League. She made speeches all over Britain where she called for an early and just peace settlement. Inspired by the Russian Revolution Snowden joined with other socialists to establish the Women's Peace Crusade. She was both secretary and treasurer of the organization.

After the war Snowden continued in her campaign to achieve a successful peace settlement. She attended the International Congress of Women in Zürich in 1919. She was also a delegate to the Labour International at Bern in February and to the League of Nations conference in March 1919.

Ethel Snowden made many enemies in the Labour Party. She had been very critical of those members who were unwilling to give their full support to women's suffrage. Snowden visited Russia and upset a large number of party members with her report entitled Through Bolshevik Russia (1920) that was highly critical of Lenin and the Bolshevik government. This especially upset Beatrice Webb, who had welcomed the Russian Revolution. She claimed that Snowden was no longer a socialist and was upset when she was elected to the National Executive. Webb wrote in her diary that "she (Ethel Snowden) is a climber of the worst description, refusing to associate with the rank-and-file and plebeian elements in the Labour Party."

Ethel Snowden was invited to stand for one the Leicester constituencies in the 1922 General Election, but she decided to devote her energies to help Philip Snowden win his seat at Colne Valley and to concentrate on her work for world peace.

In 1926 Ethel was made a member of the BBC Board of Governors where she clashed with the Director General, John Reith, who wrote in his diary: "What a poisonous creature she is". Reith's biographer, Ian McIntyre argues in The Expense of Glory: Life of John Reith (1993) that she was "fearsome when crossed, with an unerring knack of squeezing the last drop of drama out of the most trivial incident". In 1932 Ethel was not reappointed to the BBC and this marked the end of her public career.

In 1947 Ethel Snowden suffered a stroke and was confined to a nursing home, and she died of a second stroke on 22nd February 1951 at 28 Lingfield Road, Wimbledon.

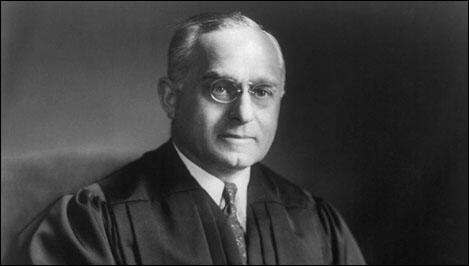

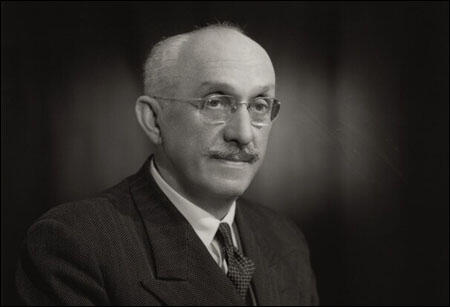

On this day in 1965 Felix Frankfurter, the son of a Jewish merchant, was born in Vienna, Austria. Twelve years later the family emigrated to the United States. After graduating from New York City College in 1902, Frankfurter entered Harvard Law School. He studying for his degree he also edited the Harvard Law Review.

In 1906 Henry Stimson, a New York City attorney, recruited Frankfurter as his assistant. When President William Howard Taft appointed Stimson as his secretary of war in 1911, he took Frankfurter along as law officer of the Bureau of Insular Affairs.

Frankfurter also became involved in the Tom Mooney case. According to Robert Lovett: "Felix Frankfurter, on a mission to examine and report to President Wilson on labor difficulties in the West, saw through the plot and warned the president of the danger in the execution of an innocent man whose fate was exciting workers all over the world. After commutation of the sentence to imprisonment for life, the long struggle began. One by one the folds of perjury were peeled away until the nucleus of the noxious growth was reached."

When Stimson lost office in 1914, Frankfurter returned to the Harvard Law School as professor of administrative law. In 1918 he decided to spend time in London. His friend, Graham Wallas, a tutor at the London School of Economics, asked one of his students, Ella Winter, if she wanted to work for him: "A good friend of mine has come to London on a highly confidential mission and asks me to suggest someone to help him... Felix Frankfurter is a professor at the Harvard Law School and Chairman of the War Labour Policies Board in America, and is here to learn what he can from England's experience. Would you like to work for him."

Winter met Frankfurter at Claridge's Hotel and wrote about it in her autobiography, And Not to Yield (1963): "He was a short, mercurial man, with glasses and a cleft chin, who smiled, talked in quick staccato phrases, flung questions at one, while attending to twenty other matters at the same time. His smile showed a row of dazzling teeth. Even at rest he seemed in motion. He was warm, friendly, trusting, and assumed so immediately and unquestionably that I would do this job, indeed that I could do anything, that doubt, fear, hesitation vanished."

As a research assistant and secretary for Frankfurter, she attended the Versailles Peace Conference in 1919. Frankfurter asked her to take a message to Lincoln Steffens. "He's a great wit, Steffens is, fond of saying things differently. He's an American newspaperman, much older than you, in his early fifties; he muckraked our cities, knows a lot about politics. You can learn from him, he'll give you a different picture than you got at the London School of Economics." Ella Winter later recalled: "The man was not tall, but he had a striking face, narrow, with a fringe of blond hair, a small goatee, and very blue eyes, and he stood there smiling. The face had wonderful lines... There was something devilish - or was it impish? - in the way this figure stood grinning at me." Winter and Steffens married in 1924.

Frankfurther acquired a reputation for holding progressive political views. A founder member of the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) he criticised the Tennessee Anti-Evolution Law. He also joined forces with John Dos Passos, Alice Hamilton, Paul Kellog, Jane Addams, Heywood Broun, Eugene Lyons, William Patterson, Upton Sinclair, Dorothy Parker, Ruth Hale, Ben Shahn, Edna St. Vincent Millay, Susan Gaspell, Mary Heaton Vorse, John Howard Lawson, Freda Kirchway, Floyd Dell, Katherine Anne Porter, Michael Gold, Bertrand Russell, John Galsworthy, Arnold Bennett, George Bernard Shaw and H. G. Wells in the campaign to overturn the death sentence imposed on Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti.

Isaiah Berlin saw Frankfurter give a lecture when he was a student at Corpus Christi College: "He talked copiously, with an overflowing gaiety and spontaneity which conveyed the impression of great natural sweetness; his manner contrasted almost too sharply with the reserve, solemnity and, in places, vanity and self-importance of some of the highly placed persons who seated themselves round him and engaged his attention. He spoke easily, made his points sharply, stuck to all his guns, large and small, and showed no tendency to retreat from views and political verdicts some of which were plainly too radical for the more conservative of the public personages present".

Frankfurter gave legal advice to Franklin D. Roosevelt when he served as governor of New York (1929-1932). When Roosevelt became president he often consulted Frankfurter about the legal implication of his New Deal legislation. He also arranged for some of his former talented students, including Thomas Corcoran and Ben Cohen to help draft legislation. Hugh Johnson described Frankfurter as "the most influential single individual in the United States". Frances Perkins, the Secretary of Labor, admitted in her autobiography, that she often asked Frankfurter for advice on drafting legislation.

Frankfurter explained in a letter to Walter Lippmann that he supported Roosevelt's gradualism: "Mine being a pragmatic temperament, all my scepticism and discontent with the present order and tendencies have not carried me over to a new scheme of society, whether socialism or communism... Those of us who, by temperament or habit of conviction, believe that we do not have to make a sudden and drastic break with the past but by gradual, successive, although large, modifications may slowly evolve out of this profit-mad society, may find all our hopes and strivings indeed reduced to a house of cards."

William E. Leuchtenburg, the author of The FDR Years: Roosevelt and his Legacy (1995), has pointed out that Roosevelt was criticised for his relationship with people like Frankfurter: "In the New Deal years, the seats of power were no longer monopolized by white Anglo-Saxon Protestants. Commentators made much of the closeness to FDR of Jews such as his counselor and subsequently Supreme Court Justice Felix Frankfurter and his chief speechwriter Samuel Rosenman."

In 1939 Franklin D. Roosevelt appointed Frankfurter as a Supreme Court justice. Frankfurter took a strong stand on individual civil rights and this led to him being condemned as an "extreme liberal". However he upset many radicals by refusing to protect socialists and communists blacklisted during what became known as McCarthyism. His long-term friend, Alice Hamilton, asked him: "Why are we the only western country that lives in terror of native Communists. All the European countries have open and above-board political Communist parties some even have members of Parliament or whatever, and they do not have Un-Dutch Activities Committee. Look at the contrast between the English treatment of Klaus Fuchs and our treatment of the Rosenbergs. Fuchs is a scientist (which Rosenberg was not) he gave valuable atomic secrets to the Russians (Urey testified that Rosenberg did not know enough to do that) he confessed (the Rosenbergs refused to, though offered their lives as reward) Fuchs acted during the war, the Rosenbergs during peace."

Frankfurter wrote several books including The Business of the Supreme Court (1927), Justice Holmes and the Supreme Court (1938), The Case of Sacco and Vanzetti (1954) and Felix Frankfurter Reminisces (1960).

Felix Frankfurter died in Washington on 22nd February, 1965.

On this day in 1978 Marcus Lipton died.

Marcus Lipton was born on 29th October, 1900. After being educated at Bede Grammar School and Merton College, Oxford, Lipton became a barrister.

A member of the Labour Party he was elected to Stepney Borough Council (1934-37) and Lambeth Borough Council (1937-56). During the Second World War Lipton served in the British Army and reached the rank of Lieutenant Colonel.

Lipton was elected to the House of Commons in the 1945 General Election. He took a keen interest in international affairs and was a member of parliamentary delegations to several European countries.

On 23rd October, 1955, the newspaper, New York Sunday News, reported that Kim Philby was a Soviet spy. Two days later Lipton asked Anthony Eden in the House of Commons: "Has the prime minister made up his mind to cover up at all costs the dubious third-man activities of Mr. Harold Philby". Eden refused to reply but, Harold Macmillan, the foreign secretary, issued a statement a couple of days later: "While in government service he (Philby) carried out his duties ably and conscientiously, and I have no reason to conclude that Mr Philby has at any time betrayed the interests of his country, or to identify him with the so-called 'Third Man', if indeed there was one."

Kim Philby now called a press conference where he denied he was a spy. He added that "I have never been a communist and the last time I spoke to a communist knowing he was one, was in 1934". Philby accused Lipton of lying and challenged him to repeat his claims outside the protection of the House of Commons. Lipton was forced to issue a statement where he withdrew his comments about Philby.

On 23rd January, 1963, Philby fled to the Soviet Union. In his book, My Silent War (1968), Philby admitted that he had been a Soviet spy for over thirty years.

Marcus Lipton remained in Parliament until his death on 22nd February, 1978.

On this day in 1985 Florence Tunks, who never married, died in Glindon Nursing Home on Lewes Road in Eastbourne, East Sussex, aged 93.

Florence Tunks, the eldest of four daughters of Gilbert Samuel Tunks (1863–1933) and Elizabeth Hall Tunks (1866–1947) was born in Newport on 19th July 1891. The family moved to Cardiff in 1894 where Gilbert ran a mechanical and electric engineers and oven builders.

Florence became a bookkeeper and in 1913 she joined the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU). Soon afterwards she became a member of a secret group called the Young Hot Bloods that carried out acts of arson. No married women were eligible for membership. The existence of the group remained a closely guarded secret until May 1913, when it was uncovered as a result of a conspiracy trial of eight members of the suffragette leadership, including Flora Drummond, Annie Kenney and Rachel Barrett.

Tunks joined the Young Hot Bloods. It has argued that this group probably included Helen Craggs, Olive Hockin, Kitty Marion, Lilian Lenton, Miriam Pratt, Norah Smyth, Clara Giveen, Hilda Burkitt and Olive Wharry.

Florence was paired with an experienced fire-bomber, Hilda Burkitt, who was on the run at the time after working with Clara Giveen in Yorkshire. On 25th November 1913 Burkitt was arrested with Giveen for attempting to set fire to the grandstand at the Headingley Football Ground the property of The Leeds Cricket, Football and Athletic Company. However, both women managed to escape and went into hiding.

On 11th April 1914 Tunks and Burkitt arrived in Suffolk for two weeks of arson. "They then moved through Suffolk, riding bicycles across the countryside and leaving phosphorus in haystacks, which would combust a day or so after they had left."

On 17th April they bombed the Britannia Pavilion on the pier in Great Yarmouth had been reduced to "a shapeless mass of twisted girders and charred woodwork." The owner of the Pavilion received a letter bearing one word, "Retribution", and a "Votes for Women" postcard was found on the sands with comments about Reginald McKenna, the Home Secretary: "Mr McKenna has nearly killed Mrs Pankhurst. We can show no mercy until women are enfranchised."

Tunks and Burkitt then travelled to Felixstowe where they took a room at Mayflower Cottage, the home of Daisy Meadows, whose father, George Meadows, was a bathing-machine proprietor. Daisy remembered the woman arriving with six cases of luggage and a bicycle. Two days later they said they were going to the theatre in Ipswich. Daisy said in court: "I didn't see them go out and didn't see them again until about five minutes to nine next morning."