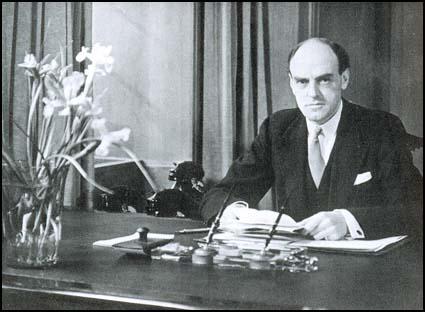

John Reith

John Reith was born Stonehaven, Scotland on 20th July, 1889. His father, Dr. George Reith, was a minister of the United Free Church of Scotland. After being educated at Glasgow Academy Reith served an engineering apprenticeship in London.

On the outbreak of the First World War Reith joined the British Army. He was appointed as a Transport Officer and sent to France in November 1914. He was soon in conflict with his Commanding Officer, Robert Douglas and the Adjutant, William Croft. He later recalled: "No bath water boiled more vehemently than did my indignation." As his biographer commented: "It was a lifelong characteristic of John Reith that he could not get on with other men, especially those in authority."

Colonel Robert Douglas eventually told Reith that he was being sent home. Before this could be arranged he drank water from a farm well and became violently ill. Suffering from dysentery he was sent to hospital in England.

In September 1915 Lieutenant Reith joined the Highland Field Company Royal Engineers. He arrived on the Western Front during the major offensive at Loos. His first task was to mark out a support trench seventy yards behind the new front line. He later wrote in his autobiography, Wearing Spurs: "I had never witnessed such sights before; this was indeed a battlefield. I had seen dead men and dead horses but never in these numbers."

On 7th October 1915 Reith was sent to repair a section of a front-line trench destroyed by a mine. While carrying out the work he was shot in the head by a German sniper. Some of the bone in his face had been shot away and he lost a lot of blood but he was not dangerously wounded.

Reith was sent to Scotland to recover and after he was released from hospital he joined the staff of a munitions factory in Gretna. In March 1916 he was sent by the Ministry of Munitions to the United States to buy rifles. On his return he was transferred to the Royal Marine Engineers.

At the end of the war, Reith returned to Glasgow to work in engineering. After working briefly for the Conservative Party, in December 1922 was appointed general manager of the British Broadcasting Company, an organization was set up by a group of executives from radio manufacturers.

During the 1926 General Strike Reith came into conflict with the government when he attempted to allow all parties the opportunity to comment on the radio. Eventually, he gave in to the Prime Minister, Stanley Baldwin, and imposed strict censorship and even turned down a direct request from the Labour Party leader Ramsay MacDonald to speak to the country.

In 1927 the government decided to establish the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) as a broadcasting monopoly operated by a board of governors and director general. The BBC was funded by a licence fee at a rate set by parliament. The fee was paid by all owners of radio sets. The BBC therefore became the world's first public-service broadcasting organization. Unlike in the United States, advertising on radio was banned.

Reith was appointed director-general of the BBC. Reith had a mission to educate and improve the audience and under his leadership the BBC developed a reputation for serious programmes. Reith also insisted that all radio announcers wore dinner jackets while they were on the air. In the 1930s the BBC began to introduce more sport and light entertainment on the radio.

It was later revealled that Reith was a great admirer of Adolf Hitler. On 9th March 1933 Reith wrote "I am certain that the Nazis will clean things up and put Germany on the way to being a real power in Europe again.... They are being ruthless and most determined". Later, when Prague was occupied, Reith wrote: "Hitler continues his magnificent efficiency."

Reith was also accused of acting like the Nazi Germany government. In the House of Commons, the Labour MP, Hastings Lees-Smith, argued: "The BBC is an autocracy which has outgrown the original autocrat... It has become despotism in decay... the nearest thing in this country to Nazi government that can be shown... If I talk to any employee of the Corporation, I am made to feel like a conspirator."

The BBC began the world's first regular television service in 1936. Two years later Reith was forced to resign his post at the BBC by Neville Chamberlain. Reith now became chairman of Imperial Airways.

On the outbreak of the Second World War Reith was invited to join the government. Elected to the House of Commons for Southampton, Reith was appointed as Minister of Information in January 1940. When Winston Churchill replaced Chamberlain in May 1940 he appointed Reith to the post of Minister of Transport. Five months later he was given a peerage and given the job of Minister of Works and Buildings. However, the two men did not get on and Churchill eventually dismissed him from his government post as being too difficult to work with. He was however, granted a peerage and he became Baron Reith of Stonehaven.

After the war Reith served as chairman of the Commonwealth Telecommunications Board (1946-50). He also wrote two volumes of autobiography, Into the Wind (1949) and Wearing Spurs (1966).

The Independent Television Authority was created on 30 July 1954 ending the BBC's existing broadcasting monopoly. In the House of Lords Lord Reith complained: "Somebody introduced Christianity into England and somebody introduced smallpox, bubonic plague and the Black Death. Somebody is minded now to introduce sponsored broadcasting ... Need we be ashamed of moral values, or of intellectual and ethical objectives? It is these that are here and now at stake."

John Reith died in 1971.

Primary Sources

(1) John Reith, Wearing Spurs (1966)

In a sense I had been looking forward to war, and for years; now it was coming. It was an entirely personal affair; no thought of what it might mean to home, or country, or civilisation.

I was a week over twenty-five, and in a thoroughly unsettled state anyhow. My family had decided that I should be an engineer; and, though I knew it was all wrong, I had no reasonable alternative to advance. Having begun the long apprenticeship, however unattractive and even distasteful the prospect, I was determined to see it through; and did. And then, having acquired the recognised qualifications theoretical and practical of an engineer, despite strong family discouragement, but because I was sure there was nothing for me in Glasgow, I had made for London. There, six months earlier, I had joined the great Pearson contracting firm, or rather had gotten a job from them. But the future was displeasing. That very week the discovery that my chief, the sub-agent, with fifteen years' service, was drawing only £250 per annum had numbered my days with Pearson's; new arrangements were well in hand. War. The problem for the time being was otherwise solved.

(2) Reverend George Reith, letter to John Reith (14th November, 1914)

It is rather a shock to your mother and me to find that you are off to the Front; and we can only pray God to be with you every moment; to give you strength and comfort and confidence in every duty to be laid upon you; and to let the assurance of Christ's presence sustain you in every hour of danger. You are doing a great work in defending your country - the greatest honour that can come to men in this world, or one of them at least. Our country's glory and good name are committed to your care for the time; and the mere thought of that should inspire you with high resolve to do all you can do. And then the cause is a righteous one if ever there were a righteous cause. God is and must be on our side as we contend for honour and faithfulness among nations; and we shall be on His side if in our own hearts we repent of all our national sins and seek that this terrible business be overruled for our spiritual welfare as a people. Keep close to Christ, dear boy. Make sure that your heart is His; that whatever happens you are fighting under Him as captain; no ill can befall you then.

(3) John Reith, Wearing Spurs (1966)

I did not envy the companies the regular trench duty on which they were soon to embark; Transport felt well out of all that. I had by now a fairly clear idea of the respective duties and dangers of an ordinary regimental officer vis-a-vis an out-of-trench specialist such as the Transport Officer. As to danger there was little to choose. At the time of the regular evening "hates" the Transport Officer was pretty sure to be around in spots most likely to engage the enemy's attention by gun and hand gun, his colleagues being "safe in the trenches". Ration dumps were usually unhealthy; traffic to and fro the trenches always liable to unpleasant interferences. But he did not have the ghastly boredom and discomfort of trench life; the incessant danger of snipers, trench mortars and direct hits by high explosive with none of the interests of behind-the-line life. The Transport Officer could make himself tolerably comfortable in a billet, hot baths, proper meals, and a bed to sleep in; could mount his horse and ride round the countryside from one place of business to another; had wagons and carts to dispatch for this duty and that; had interesting work to do, room to move about, new people to meet; a job, and a very good one. When I left Transport for trench work I was, in official parlance, "returned to duty" forsooth. And if there were little doubt, in the days of entrenched stalemate, which were the better occupation there was none in aggressive war or in movement of any kind. The Transport Officer and his section might be shelled to extinction but they would not be required to thread their way through barbed wire entanglements in the sweep of machine-gun fire.

We were soon to become accustomed, some of us anyhow, to shelling. When one hears the vicious snap of a bullet the danger is past. The whine of a shell, pitch and volume according to nature and size, heralds its coming. Coming where? "Most thrilling to hear the shells whistling through the air and to wonder how near they're going to land. Much experience of them now" - so I wrote in a letter home; and it was genuine. On the 27th it seemed that enemy gunners were searching for our Transport park, so I took the section out for route march. Nearing home again we were warned by a gunner officer to go by a detour as the enemy was sighting on a field on our route. The Boche, he said, thought there was a battery behind the hedge. "Is it shrapnel or high explosive?" I asked. Shrapnel mostly, was the reply. This certainly was inconvenient in open country as the bullets cover so wide an area when the shell bursts overhead; but a detour would have taken at least half an hour and it was getting near lunch time. While we were talking we heard a shell coming. It was high explosive and struck the field a hundred yards away. It was worth risking; it would be good experience for the section. Each cart and wagon went by singly at the gallop-a funny sight. The Doctor's cart came last-a tiny affair drawn on this occasion by a large horse and driven by a large man. His seat had collapsed and he was sprawled on the floor one hand on the reins the other clutching his glengarry.

(4) John Reith, Wearing Spurs (1966)

Christmas morning was bright and everything in the garden white with hoar frost. I did not propose to wage any war today. Whitelaw and I set ourselves to prepare a cellar for the Christmas dinner. We took two tables down and set them T shape. The maids exhumed tablecloths, cutlery, crockery, flower vases, bob-bon dishes and four massive silver candelabra holding four candles each. They were much excited about it all. When we had finished it seemed to me that the tables would have done credit to any establishment. There were nine of us-the Transport "staff". Opposite me at the end of the T was the sergeant; the others were Wallace, Whitelaw and Anderson (corporals), Annan (cyclist orderly), MacLelland (groom), Tudhope (batman), Ferguson (NCOs' orderly). We sat down at 7.30 pm and broke up at 12.30 am. Instead of turkey we had four chickens but everything else was according to custom. How surprised our friends at home would have been had they seen us. One of the maids kept to the kitchen, but the third sister had been impounded from No 82 so we had two to wait at table. They had rigged themselves in proper uniform for the occasion.

(5) John Reith, Wearing Spurs (1966)

We had been more than usually free from the attention of German gunners recently but now they were on to us again; at 8.15 on the morning of February 27th I was going through the usual mental exercises preparatory to getting out of bed when a shell landed close by. This was unusual and rather annoying; shells might be expected any time after dusk, but not with the morning milk. Thirty seconds later another arrived and burst properly in a house immediately on the opposite side of the road, several of our windows being broken. I went into the road in my pyjamas. Wallace, also in pyjamas, was hanging out of a shattered upper storey window a broad grin on his face. He had been wakened, he said, by bits of glass falling on his bed; apparently he had not heard the first shell. I was about to shout to him to come down at once and take cover or he would have worse than glass falling on him. But I was lost in a sort of philosophic contemplation of his indifference to danger; he was seeing something funny in it. And it was funny. So, feeling rebuked but glad I had said nothing, I returned to my room to dress.

(6) John Reith, Wearing Spurs (1966)

Next day, April 13th, came my first spell of trench duty. A and B companies were still doing an in-and-out routine with C and D, three or four days in, the same number out. As Kennedy was in charge of the half Battalion in trenches, I, though not to be promoted captain, was OC company. In letters home, in whatever fulminations I had indulged against the CO and Adjutant, whatever sorrow expressed at leaving Transport and distaste for ordinary infantry work, I had made it clear that I had no qualms, on the score of danger, about trench life. Of course at 6 ft 6 in I was inconveniently tall; parapets would be too low and I should probably be caught. But I did not greatly care though I wanted a run for the money, and in my Diary I wrote that I was "looking forward tremendously to going into trenches"; there at any rate we should see very little of CO or Adjutant.

At 9.00 pin Kennedy and the OC of B company and I set off ahead of the men to take over from our colleagues of the other half Battalion. The OC of C company took me along his front which now passed to my company, along the wire outside, telling me what he had been doing and what needed to be done. As I knew next to nothing about hours of watch and stand-to and suchlike Begg made out a list of duties. Officers did two hours each and then as many as possible off before their turn came again; during stand-to all officers were on duty. Morning stand-to was ordered as soon as day began to break, and the night sentries who had hitherto stood on the firing step with head and shoulders above the parapet now crouched below it, periodically looking over night sentries peeping. Halfway through the morning twilight, night sentries would be relieved by day sentries-about an eighth of the number-day sentries peeping. The rest of the men were standing-to in the trench throughout, this being the time when an attack might be expected. Finally with full day light, stand-down and day sentries. By day the sentries stood in the trench watching for signs of the enemy (when they had nothing better to do) through periscopes. The same sort of routine was carried out in the evening. Day sentries became at stand-to, day sentries peeping; changed to night sentries peeping, and these at stand-down to night sentries.

There was often a difference of opinion between Kennedy and the rest of us as to when stand-to should be given. He never liked taking risks. Most of us were inclined to wait till the last minute and keep the stand-to period as short as possible. It was an infernal nuisance, especially to those who had only come off watch an hour or two earlier.

I was up all this first night learning the ropes. Kennedy told me to sleep in the HQ hut and this suited me as it was more commodious then A company officers' one. It was about six foot square by five foot high but under the parapet was a bunk seven foot long. The B company OC fed in this dug-out but slept elsewhere. The parapet was indeed far too low for me ; the other A company subalterns obviously expected me to be jumpy, and they were solicitous and kindly. Before the night was out I think that they and most of the men had realised that the ex-Transport Officer was not afraid of his new job. I was lucky in having no nerves to speak of - not that sort anyhow.

(7) John Reith, Wearing Spurs (1966)

I did my best to take an interest in the members of my platoon personally. In manual exercises and in extended order drill in a field I could take none; and they knew it. I was supposed to censor their letters home, but I informed them that they were on their honour not to say things they should not say, and I handed over the censor's stamp to the sergeant. I was thankful when our three days in billets were over and we were back in trenches again. I was still dreaming about Sailaway and Transport, still bewildered almost every time I woke, but there was at least a chance of something happening in the trenches and one was clear of CO and Adjutant.

(8) John Reith, Wearing Spurs (1966)

There was a good deal of uneasiness about the line that night. The Germans were continually sending up star shells and they had a second searchlight working. Next day there were tales of unusual activity on their side; an attack was to be expected. Gas might be used, we heard, and so goggles and primitive respirators and a supply of bicarbonate of soda were coming up. Some of us wanted to patrol up to the enemy's lines and see if we could find anything interesting, but Kennedy vetoed the idea. As a matter of fact he stopped two or three stunts which one or other of us conceived. We were annoyed with him at the time but perhaps owed him our lives. Next night things were jumpier than ever. I went beyond the sapheads and lay for some time anxious to hear and see if the Germans were cutting their wire, as this would definitely have portended an attack. There was nothing unusual except that the German parapet was more strongly manned than before. In the morning we were told that their wire had been cut but I knew it was not so not on our immediate front. However, an attack was expected, and in the afternoon our guns put some shells along the enemy line. We took special precautions that night but apart from a salvo or two about midnight nothing happened. We were told that the reserve breastworks behind us were manned by one of the other battalions of the Brigade and it was a comforting thought. In the early morning it came on to rain and things were soon in a horrid mess - my first experience of wet trenches. One of our best sergeants was killed-one of my old Larbert viaduct men. He had spent a good part of the night rigging up a new sniping hole for himself and had been looking forward to an interesting and satisfactory day. They got him before he had time to get one of them. We were to be relieved that evening and, being anxious to give the C company OC a proper report on the condition of the wire, I went out just after dusk and was able for the first time to see the whole length of it properly. The German trench was about three hundred yards away from ours and as their parapet was visible I was surprised that there was no sniping. Later, back in the trench I reflected on the unevenness of my experience and that of the unfortunate sergeant earlier in the day. I wondered if the explanation were that whereas I was on a lawful routine occasion, the harmlessness of which the enemy recognised, he, on the other hand, had been making a nuisance of himself and therefore had to be dealt with - in fact disposed of. No-too fancy that would be.

(9) John Reith, Wearing Spurs (1966)

No lice had so far come my way, but I was always in fear of them. On going into trenches I used to spray about a gallon of lysol over my bunk below the parapet and generally about the hut; now, with the receipt from home of a box of mercurial ointment, I took for the first time to wearing my identity disc, drawing the string through the ointment. I had heard that this was a louse deterrent. It made one's neck dirty but there was never a louse found.

(10) John Reith, Wearing Spurs (1966)

Trenches again on the 15th and next afternoon between forty and fifty shells came over in three quarters of an hour. The first one struck the parapet just beside the hut where I was writing up my Diary and a shower of sand and earth was blown on to me. I noted afterwards that my hand had not moved off the letter which at the moment had been in the process of formation. Later that evening, just after stand-to had been given, I was sitting in the HQ hut when the Adjutant arrived. Kennedy was there and two other officers; I was furthest inboard and could not easily remove myself. He started off about the wire and advanced posts, and this irritated us as he had never been out in front as far as we had seen. When he had finished his remarks there was a pause. I am sure we all, even Kennedy, would have liked to tell him to go to hell. It was I who came nearest doing so. "Wouldn't you like to go out in front, Captain X?" And I said it just so-quietly; but I do not think I had ever put such concentrated venom into a question; and some of it, anyhow, was apparent. There was a tense silence but only for about two seconds. "I should love to," he replied. I suppose I hoped I was taking him to the slaughter and I did not object to being slaughtered myself in the process. What a dramatic end to the feud, I thought, as I pushed my way from the dug-out.

Twenty or thirty yards along the trench was the entrance to the nearest sap. Here was a tunnel under the parapet large enough for a man to crawl through; then the sap-a shallow trench, stretched ahead for twenty-five yards, passing under the main wire, though it was also possible to walk through the wire. The hole in the parapet was blocked by a big chevaux de frise of barbed wire. We hardly ever used the hole, our normal exit being over the top of the parapet - expeditiously over, of course. Pointing to the hole I said : "That is one way of getting into the sap. We usually go this way." I climbed up on the parapet and stood there full height. It was a silly bit of bravado for the German trench was still visible. The Adjutant said he preferred to go "the proper way' and proceeded to pull the chevaux de frise from the hole. Arms akimbo, I stood watching him disappear underneath and when he emerged on the other side I jumped down. While he crawled along the sap to its head I walked on the open ground above him. He glanced round at the saphead and we returned the way we had come - he under the parapet when we reached it, I over. There had been no sniping at us. By the time he had come through the tunnel I had made off. If I had had better luck than I deserved, so, I thought, had he. But I had never taken quite such a risk before.

(11) Harold Laski on John Reith, The Daily Herald (31st March, 1931)

His deep-set eyes look as though, at any moment, they may let loose a tempest. He is vehement, determined, aggressive, masterful. He works easily with you while you agree with him. When you disagree, no one can quite tell, least of all he, what will be the outcome ... There is a fanatic in him. It is one of his gifts and one of his limitations. It explains his power of work, his energy and his drive. But it means also that he carries about with him a bundle of dogmas - social, religious, ethical, political - and he has a tendency to make them the measure of all things and all men.

(12) John Reith, diary (24th November 1932)

An anxious afternoon for all concerned in the BBC. So many things that might go wrong. The complications and the delicacies of timing and switching and relaying from one part of the world to another. Nothing went wrong; all excelled. The King's message impressive and moving beyond expectation. It was a triumph for him and for BBC engineers and programme planners. Reports were received with extraordinary rapidity from all over the world and two thousand leading articles were counted in Broadcasting House. A selection of letters, received from all over the world, were bound into a volume and sent to the King, who was said to be much moved.

(13) John Reith, diary (9th March 1933)

Dr. Wanner (head of broadcasting for southern Germany) to see me in much depression. He said he would like to leave his country and never return. I am pretty certain, however, that the Nazis will clean things up and put Germany on the way to being a real power in Europe again. They are being ruthless and most determined. It is mostly the fault of France that there should be such manifestations of national spirit.

(14) Marista Leishman, My Father: Reith of the BBC (2008)

Over lunch at the Carlton in 1935, he (John Reith) told Marconi, who was a little surprised, how much he had always admired Mussolini for having achieved "high democratic purpose by means which, though not democratic, were the only possible ones". Again, restless and dissatisfied with the BBC, and remarking how much he admired Hitler for his magnificent efficiency, he mused that his real calling was for dictatorship.

Professor Asa Briggs could not help noting that John's notions of social and industrial regimentation inclined towards fascism: John made no apology for announcing that he really admired the drastic action taken by Hitler. At home, he liked to draw Muriel's attention to the way in which some of her relatives looked Jewish - with the implication that she did too - as though that were a black mark. I began to think that, in many ways, my father must be a rather terrible person. When he made his loud and public confessions, he was certainly not taking responsibility for them, any more than in showing his emotional nakedness he minded, or was embarrassed about, others being emotionally bullied or themselves embarrassed. I thought he ought to mind - or, at the very least, notice.

(15) Hastings Lees-Smith, House of Commons (17th December, 1936)

The BBC is an autocracy which has outgrown the original autocrat ... It has become despotism in decay ... the nearest thing in this country to Nazi government that can be shown... If I talk to any employee of the Corporation, I am made to feel like a conspirator.

(16) Marista Leishman, My Father: Reith of the BBC (2008)

Even when Dr Wanner was later "too terrified to say much about conditions in Germany and said he would be shot if he did", John was reluctant to acknowledge the truth about the Nazis, actually arguing in their favour with another German contact in November 1933. It was not until 1936 that he accepted Dr Wanner's tale of the "awful happenings in Germany", eventually passing private information to the Foreign Office. But still he did not reject the Nazi regime; and, even in March 1939, when Prague was occupied, he wrote: "Hitler continues his magnificent efficiency".

(17) John Reith, Into the Wind (1949)

The car passed, recognised and unchallenged, through the Castle archway, up and round to the door of the private apartments. A footman, scarlet-coated, opened without summons; within stood the superintendent and housekeeper. I asked to be taken to the room where the broadcast would be made. A corridor with three rooms in the Augusta Tower - the modest suite which the former King had always himself used. In a little sitting room the microphones had been installed; next door the engineers had their apparatus; at the end of the corridor was the bedroom. Everything was in order, as of course I knew it would be; nothing for me to do but wait; time 9:45.

The housekeeper was lighting a fire in the bedroom: I would sit there and watch it grow. The superintendent appeared in agitation. His Majesty, he said - and what else could he have called him - was already on his way from Royal Lodge. I knew he was to dine there with his mother and the members of his family. Well that was all right, I said, continuing to sit. But apparently it was not all right by the superintendent; His Majesty would arrive any moment. Well, that was still all right by me. The agitation increased, and, since time was pressing, tactful insinuation had to give place to direct suggestion; would I not receive His Majesty on the doorstep. Apparently he felt himself, with or without housekeeper, inadequate for the purpose. I was minded to tell the superintendent that it was no lack of imaginative courtesy that had set me down by the bedroom fire; that it seemed off, if not improper, that I should receive on the doorstep him who a few hours earlier was the owner; that I was in no sense the host of the occasion. But I let it go; perhaps he was right. At speed, therefore, I returned to the entrance hall - just in time. I wondered, naturally, what sort of mood the former King would be in; how he would behave. He had had some weeks of torturing indecision and suspense; now he had taken unprecedented, shattering action. Was I to adjust face and manner accordingly? In the hurried progress from the Augusta Tower, pursued at increasing remove by the superintendent, I had realised that the question must now be settled. The car was drawing up by the open door. I would behave absolutely normally, as if nothing untoward or exceptional were afoot - just as in Broadcasting House.

He was wearing a fur coat over a light suit, smoking a cigar. A dog emerged next; it went about its own business; I do not remember to have seen it again; have since wondered what became of it; have even forgotten what kind of dog it was - a Cairn or something of that sort. Someone else was getting out of the car now. No one had been able to tell me who, if anyone, would be accompanying. It might be the new King, in which case my position on the doorstep would be odder than ever. It was a man I had never seen before. The former King seemed to be in no different mood from usual. "Good evening, Reith", he said. "Very nice of you to make all these arrangements and to come over yourself." He introduced his companion - Walter Monckton. I knew how much he had meant to his master of recent weeks.

On the way upstairs he asked if all were in order. Yes, I said, and no chance of anything going wrong; everything had been duplicated; and the civil war in Spain had not prevented Madrid ringing up that afternoon to ask permission to relay his talk. That amused him. Some of the furniture in a corner was covered with dust sheets; he was surprised; then said he remembered that some structural alterations had to be made. Presumably he had ordered them himself...

On other occasions he used to have the sheets of his manuscript mounted neatly on bits of cardboard; he had told me that he did this himself. Tonight there was no mounting; ever so many alterations in the script. It seemed he still had some to make, so I went out, leaving him and Monckton at work together. In the corridor I found Clive Wigram, Deputy-Constable and Lieutenant-Governor of the Castle; he said he had thought he would just come across. He would not go into the sitting room, so I told him there was a fire and a wireless set in the bedroom; he might like to listen there. It was nearly ten o'clock, I left Wigram in the bedroom and I returned to the sitting room.

At half a minute to ten I sat before the microphones at the table waiting for the signal - the tiny red light that would bring the ears of the whole world into that little room. My voice would carry to the ends of the earth. A thousand million people were there to hear what the man standing beside me was about to say. I thought with quiet satisfaction of the vast and flawless efficiency of the organisation behind the now dull circle of glass. The engineers next door. The control room at headquarters with its innumerable circuits, panels, distributing boards, switches, plugs and lights. All the regional and Empire control rooms and transmitters; all the aerials with their carrier waves vibrating through the infinities of ether. All the links with control rooms and transmitters in a thousand centres overseas. Especially the BBC engineers, in utter competence at their posts. All the... "This is Windsor Castle. His Royal Highness the Prince Edward."

I slipped out of the chair to the left; he was to slip into it from the right. So slipping, he gave an almighty kick to the table leg. And that was inevitably and faithfully transmitted to the attendant multitudes. Some days afterwards I was invited to confirm or deny a report that, having made the announcement, I had left the room, slamming the door. It was even suggested that, by doing so, I was not just forgetful of microphone sensitivity, but was indicating disapproval of what was to follow. I had left the room, but no microphone would have noted it.

After the broadcast I walked with Wigram for a little; he was going back to work for a few months to help the new King. Fortunate, I thought, the King and any king who could command such wisdom and devotion of service as Clive Wigram had given. Then, with an "all-world OK!" from the engineers, I returned to the sitting room, where Monckton had stayed during the broadcast; gave the report to the Prince....

The Prince came to the head of the stairs with me. He referred to his visits to Broadcasting House; he had always enjoyed coming there. He had made great use of broadcasting; it had helped him in many ways; he hoped he would be able to use it again. I could only say I hoped so too. "Good Luck, sir", I said, coming to attention; bowed, shook hands. He looked up at me and smiled; seemed to be going to say something more. For two or three seconds no movement; then I bowed again; turned and went down the stairs. I felt there was something I ought to have said; wanted to say; could not.

So ended this reign of only one year's length.

(18) Tom Hopkinson, Of This Our Time (1982)

Our struggle over post-war planning led to one further skirmish before the Second World War ended and the future turned into the present. This involved the awe-inspiring figure of John Reith. Following his long spell at the BBC and the later task of transforming Imperial Airways into a state-run corporation, Reith had been brought into politics by Chamberlain, who made him Minister of Information in January 1940. When Churchill took over in May, he gave Reith the post of Minister of Transport to which he applied himself with his habitual energy. He was also just starting to feel at home in the House of Commons when in October 1940 he was shifted again, this time to the Ministry of Works, with a peerage which carried him out of the Commons and into the Lords.

Churchill disliked Reith, whom he blamed for having kept him off the air during the crucial years of the thirties, and may have imagined that, shoved into the Lords, in a post that had little to do with the conduct of the war, he would fade into obscurity. Instead Reith set to work, with determination and efficiency, to make the most of this new opportunity and in particular to extend the powers of his office. One aspect of his work was concerned with repairing bomb-damaged buildings, but another involved the planning and rebuilding of cities after the war ended, thus opening up the whole field of postwar reconstruction. It did not take Reith long to draw up an imposing list of objectives which included a central planning authority: "controlled development of all areas and utilization of land to the best advantage; limitation of urban expansion; redevelopment of congested areas; correlation of transport and all services; amenities; improved architectural treatment; preservation of places of historic interest, national parks and coastal areas." Followed, inevitably, by his recommendations for immediate action.

(19) Herbert Morrison, An Autobiography (1960)

His (Lord Reith) wonderful work in forming the British Broadcasting Company and later organizing and running the BBC proved his capabilities, but as a minister he was not happy even if he did his best to be a success.

At the outset he was Minister of Transport, with which was merged Shipping. By October, 1940, he was given a peerage and made Minister of Works. In most of his career he had had a free hand - it is, of course, a byword that he ran like an autocrat the motley and varied entity of the BBC, with its technicians, semi-civil service officials and temperamental artists somehow having to get on together. He found irksome the cooperation and compromise necessary in ministerial life.

I think he felt circumscribed and he was always looking for something more to tackle. Often at ministerial meetings a problem would arise which could not be clearly defined as the task of a particular department. Before the right niche could be discussed Reith would be saying "I'll do it, I'll do it. My department can handle that."

Some of his colleagues were happy enough that an awkward job should be taken off their shoulders, but others were reasonably apprehensive and annoyed.

I told him when we were waiting at No. 10 one day that there would be jealousies and frictions if he didn't watch out. "Sometimes it almost sounds as if you're canvassing for orders," I said.

His rather dour Scottish mind could not really see the implication. "There's no harm in it," he protested. "A problem comes up and I'm willing to solve it by taking it on."

The touchiness of some otherwise intelligent and dispassionate men, and the subtleties of cooperation in ministerial work escaped him.