The Western Front

On 3rd August, 1914, German troops crossed the Belgian border in the narrow gap between Holland and France. The German First and Second Armies swept aside the small Belgian Army and by 20th August had occupied Brussels.

The French commander-in-chief, Joseph Joffre, ordered his Fifth Army and the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) to meet the German advance. The German defeated the French at the battles of Sambre (22nd August) and Mons (23rd August). By the end of August the Allied armies were in retreat and General Alexander von Kluck and the German First Army began to head for Paris. What was left of the French Army and the BEF crossed the River Marne on 2nd September.

Joffre ordered a counter-attack which resulted in the Battle of the Marne (4th to 10th September). Unable to break through to Paris, the German army was given orders to retreat to the River Aisne. The German commander, General Erich von Falkenhayn, decided that his troops must hold onto those parts of France and Belgium that Germany still occupied. Falkenhayn ordered his men to dig trenches that would provide them with protection from the advancing French and British troops.

The Allies soon realised that they could not break through this line and they also began to dig trenches. After a few months these trenches had spread from the North Sea to the Swiss Frontier. For the next three years neither side advanced more than a few miles along this line that became known as the Western Front.

Primary Sources

(1) Sergeant William Edgington was a member of the British Expeditionary Force attempting to stop the German advancing into France. He described his experiences in his diary.

Monday 24th August: Retired further back and took up position at the edge of a cornfield and got heavily shelled, difficulty in getting out of the action. Big fight this day having to assist 5th Division who were in difficulties.

Tuesday 25th August: A very hot trying day. Germans seemed to be all around us. We came into action at 8.00 against Infantry and drove them back, my gun jammed.

Wednesday 26th August: Inhabitants fleeing from Germans. Marched early in the morning without orders but were en route to Ligny when we found we were on the flank of a big fight.

(2) Sergeant Albert George, of the British Expeditionary Force, later wrote about his experiences in France on 26th August, 1914.

The Germans were advancing upon us so rapidly that the General Staff could see it was useless trying to stop the furious advance, so a general retirement was ordered and it was every man for himself. In our hurry to get away guns, wagons, horses, wounded men were left to the victorious Germans and even our British infantrymen were throwing away their rifles, ammunition, equipment and running like hell for their lives, mind you not one infantryman was doing this, but thousands, and not one Battery running away, but the whole of the British Expeditionary Force.

(3) After the Battle of the Marne, the British Expeditionary Force was able to advance again as the Germans retreated to the River Aisne. Captain James Paterson, who was to be killed at Ypres three months later, described the advance in his diary.

Wednesday 9th September: Advance again north. All the villages are broken and signs of the retreating enemy are met everywhere. Dead horses, graves, etc. Nasty sights. An occasional hole where a shell has dropped with perhaps some blood about it. Ugh!

Thursday 10th September: Get off at 8 a.m., raining, very nasty. Get news at 10.30 that the Germans, who are retiring from West to North East, are crossing our front. We push on. We are shelled at 1,000 yards. Several killed and wounded. General Findlay, hit on the head by shrapnel bullet. Push on and come nasty close to high explosive German shells at the village of Priez, where we halt. Just before turning in comes news of General Findlay's death.

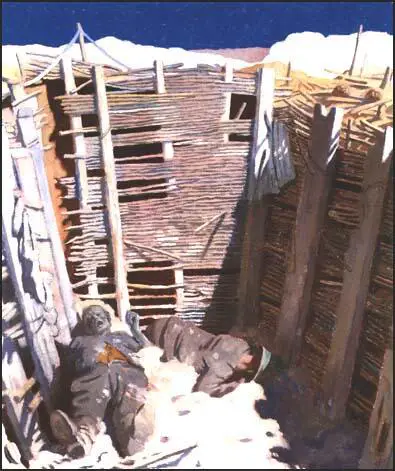

(4) William Orpen, letter to Grace Orpen (15th April 1917)

I cannot describe the impression I have formed from what I have already seen - that such a machine has been going on in over 2 years and growing bigger everyday is past comprehension, it makes one look on human beings as a different breed than one had ever imagined them before, the nobility and self sacrifice are beyond understanding. The whole thing is fine noble and bold.

Of course there is the other side, today when I had finished work, I went over some country that was really terrible, it was fought over last about 3 weeks ago, everything is left practically as it was, they have now started to bury the dead in some parts of it Germans and English mixed, this consists of throwing some mud over the bodies as they lie, they don't even worry to cover them altogether arms and feet showing in lots of cases.

The whole country is obliterated. In miles and miles nothing left at all except shell holes full of water you pick your way between them or jump at times, miles and miles of shell holes bodies rifles steel helmets gas helmets and all kinds of battered clothes, German and English, dud shells and wire, all and everything white with mud, and one feels the horrors the water in the shell holes is covering - and not a living soul anywhere near, a truly terrible peace in the new and terribly modern desert - it was a relief to get back to the road and people.

The roads behind the line are wonderful one moving mass of men, horses, mules, ammunition, guns food, fodder, pontoons and every imaginable kind of war material all struggling in one steady stream up these battered thoroughfares, all white with mud halting and struggling on again at regular intervals it is a wonderful sight full of grim determination.