British Broadcasting Corporation

The British Broadcasting Company was set up by a group of executives from radio manufacturers in December 1922. John Reith became general manager of the organization.

In 1927 the government decided to establish the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) as a broadcasting monopoly operated by a board of governors and director general. The BBC was funded by a licence fee at a rate set by parliament. The fee was paid by all owners of radio sets. The BBC therefore became the world's first public-service broadcasting organization. Unlike in the United States, advertising on radio was banned.

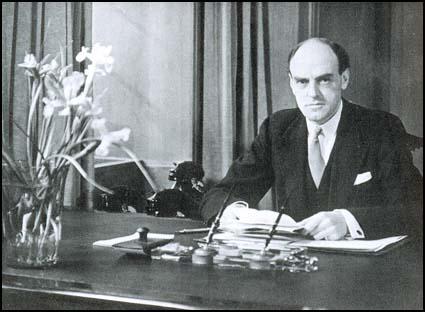

John Reith was appointed director-general of the BBC. Reith had a mission to educate and improve the audience and under his leadership the BBC developed a reputation for serious programmes. Reith also insisted that all radio announcers wore dinner jackets while they were on the air. In the 1930s the BBC began to introduce more sport and light entertainment on the radio.

The BBC began the world's first regular television service in 1936. This service was halted during the Second World War and all BBC's efforts were concentrated on radio broadcasting. In 1940 John Reith was appointed as Minister of Information

Writers such as J. B. Priestley, George Orwell, Charlotte Haldane, T. S. Eliot and William Empson were recruited by the BBC and radio was used for internal and external propaganda. This included broadcasting radio programmes to countries under the control of Nazi Germany. These radio programmes went out in 40 different languages

The BBC television service was resumed in 1946 and by the early 1950s it became the dominant part of its activities. Its broadcasting monopoly came to an end with the introduction of commercial television under the Independent Television Authority in 1954. This was followed by the introduction of commercial radio stations in 1972.

It has been claimed that BBC is the most universally recognizable set of initials in the world. For example, by the end of the 20th century an estimated 150 million people were listening to BBC World Service radio.

Primary Sources

(1) J. B. Priestley, Postscripts, BBC radio broadcast (5th June, 1940)

I wonder how many of you feel as I do about this great Battle and evacuation of Dunkirk. The news of it came as a series of surprises and shocks, followed by equally astonishing new waves of hope. What strikes me about it is how typically English it is. Nothing, I feel, could be more English both in its beginning and its end, its folly and its grandeur. We have gone sadly wrong like this before, and here and now we must resolve never, never to do it again. What began as a miserable blunder, a catalogue of misfortunes ended as an epic of gallantry. We have a queer habit - and you can see it running through our history - of conjuring up such transformations. And to my mind what was most characteristically English about it was the part played not by the warships but by the little pleasure-steamers. We've known them and laughed at them, these fussy little steamers, all our lives. These 'Brighton Belles' and 'Brighton Queens' left that innocent foolish world of theirs to sail into the inferno, to defy bombs, shells, magnetic mines, torpedoes, machine-gun fire - to rescue our soldiers.

(2) J. B. Priestley, Postscripts, BBC radio broadcast (21st July, 1940)

We cannot go forward and build up this new world order, and this is our war aim, unless we begin to think differently one must stop thinking in terms of property and power and begin thinking in terms of community and creation. Take the change from property to community. Property is the old-fashioned way of thinking of a country as a thing, and a collection of things in that thing, all owned by certain people and constituting property; instead of thinking of a country as the home of a living society with the community itself as the first test.

(3) Graham Greene, The Spectator (13th December 1940)

Priestley became in the months after Dunkirk a leader second only in importance to Mr Churchill. And he gave us what our other leaders have always failed to give us - an ideology.

(4) George Orwell, BBC radio broadcast (20th December 1941)

The Japanese successes are still very serious for us. At present the pressure of Japanese troops has died down in Malaya, where heavy casualties have been inflicted upon them. Large Indian reinforcements have been landed in Rangoon. The Governor of Hong Kong states that heavy fighting is in progress, on the island itself.

In all this we must remember that the Japanese power, though great, can only aim at a rapid outright victory. The three Axis powers together can produce 60 million tons of steel every year, whereas the USA alone can produce about 88 million. This in itself is not a striking difference. But Japan cannot send help to Germany, and Germany cannot send help to Japan. For the Japanese only produce 7 million tons of steel a year. For steel, as for many other things, they must depend on the stores they have ready.

If the Japanese seem to be making a wild attempt, we must remember that many of them think it their duty to their Emperor, who is their God, to conquer the whole world. This is not a new idea in Japan. Hideyoshi when he died in 1598 was trying to conquer the whole world known to him, and he knew about India and Persia. It was because he failed that Japan closed the country to all foreigners.

In January of this year, to take a recent example, a manifesto appeared in the Japanese press signed by Japanese Admirals and Generals stating that it was Japan's mission to set Burma and India free. Japan was of course to do this by conquering them. What it would be like to be free under the heel of Japan the Chinese can tell us, and the Koreans.

(5) George Orwell, BBC radio broadcast (6th June 1942)

On two days of this week, two air raids, far greater in scale than anything yet seen in the history of the world, have been made on Germany. On the night of the 30th May over a thousand planes raided Cologne, and on the night of the 1st June, over a thousand planes raided Essen, in the Ruhr district. These have since been followed up by two further raids, also on a big scale, though not quite so big as the first two. To realise the significance of these figures, one has got to remember the scale of the air raids made hitherto. During the autumn and winter of 1940, Britain suffered a long series of raids which at that time were quite unprecedented. Tremendous havoc was worked on London, Coventry, Bristol and various other English cities. Nevertheless, there is no reason to think that in even the biggest of these raids more than 500 planes took part. In addition, the big bombers now being used by the RAF carry a far heavier load of bombs than anything that could be managed two years ago. In sum, the amount of bombs dropped on either Cologne or Essen would be quite three times as much as the Germans ever dropped in any one of their heaviest raids on Britain. (Censored: We in this country know what destruction those raids accomplished and have therefore some picture of what has happened in Germany.) Two days after the Cologne raid, the British reconnaissance planes were sent over as usual to take photographs of the damage which the bombers had done, but even after that period, were unable to get any photographs because of the pall of smoke which still hung over the city. It should be noticed that these 1000-plane raids were carried out solely by the RAF with planes manufactured in Britain. Later in the year, when the American airforce begins to take a hand, it is believed that it will be possible to carry out raids with as many as 2,000 planes at a time. One German city after another will be attacked in this manner. These attacks, however, are not wanton and are not delivered against the civilian population, although non-combatants are inevitably killed in them.

Cologne was attacked because it is a great railway junction in which the main German railroads cross each other and also an important manufacturing centre. Essen was attacked because it is the centre of the German armaments industry and contains the huge factories of Krupp, supposed to be the largest armaments works in the world. In 1940, when the Germans were bombing Britain, they did not expect retaliation on a very heavy scale, and therefore were not afraid to boast in their propaganda about the slaughter of civilians which they were bringing about and the terror which their raids aroused. Now, when the tables are turned, they are beginning to cry out against the whole business of aerial bombing, which they declare to be both cruel and useless. The people of this country are not revengeful, but they remember what happened to themselves two years ago, and they remember how the Germans talked when they thought themselves safe from retaliation. That they did think themselves safe there can be little doubt. Here, for example, are some extracts from the speeches of Marshal Goering, the Chief of the German Air Force. "I have personally looked into the air-raid defences of the Ruhr. No bombing planes could get there. Not as much as a single bomb could be dropped from an enemy plane', August 9th, 1939. "No hostile aircraft can penetrate the defences of the German air force", September 7th, 1939. Many similar statements by the German leaders could be quoted.