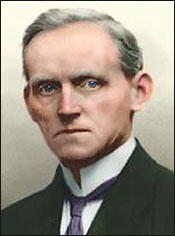

Philip Snowden

Philip Snowden, the only son and third child of John Snowden, weaver, of and his wife, Martha Snowden, also a weaver, was born in the village of Cowling, in the West Riding of Yorkshire on 18th July, 1864. His parents were devout followers of the religious ideas of John Wesley and as a boy he was brought up as a strict Methodist. (1) He was educated in the village school, where he became in course of time a pupil teacher. (2)

His father was an active Chartist and joined with a group of handloom weavers who together contributed a halfpenny a week to buy a copy of the weekly Leeds Mercury, which was then seven-pence."With these coppers he was sent to a village four miles away each week to get the paper; and then the subscribers to this newspaper met in a cottage and he read the news to them.... Those were times of great political and social excitement. The Chartist movement was affecting the industrial population, and the agitation was affecting the industrial population, and the agitation for the Repeal of the Corn Laws was at its height. They were dangerous times for those known to harbour Radical opinions. Throughout the West Riding, as well as other parts of England, men were being arrested and sentenced to long terms of imprisonment for alleged sedition and political conspiracy." (3)

John Snowden was a member of the Temperance Society and Philip followed his father's example and never drank alcohol. Philip did well at school and at the age of fifteen was able to work as a clerk in an insurance office. In 1879 the mill which employed Snowden's parents went bankrupt. The family moved to Nelson and Philip found employment as an insurance clerk in Burnley. After considering training to be a solicitor, he applied to enter the civil service and passed the examination with honours in 1886. (4)

Snowden entered the excise department of the Inland Revenue but in August 1891 he had an accident while riding his bicycle. It caused chronic inflammation of the spinal chord and paralysis from the waist down. (5) He returned to his mother's home in Ickornshaw. Two years later he was walking with the support of two sticks, but he never walked unaided again. He was deemed too weak for office work, despite his protestations to the contrary, and was discharged from the civil service. (6)

Philip Snowden and Socialism

Snowden joined the Keightley Liberal Club and he agreed to present a paper on the dangers of socialism. While researching this paper Snowden read books by Karl Marx, and Henry Hyndman. "I did not find these books so interesting and instructive as other volumes on the subject which I read." He was more impressed with the works of Robert Owen and Edward Carpenter: "I collected quite a library of old radical and socialist books and periodicals and pamphlets dating from the days of Hunt and Owen down to modern times." (7)

Snowden became converted to this new ideology. Snowden left the Liberal Party and joined the local branch of the Independent Labour Party (ILP). Snowden soon developed a reputation as a fine orator and for the next few years he travelled the country making speeches for the ILP. He drew large crowds and and was considered one of the ILP's best platform speakers. "Snowden established a reputation as a fierce critic of the establishment. He eloquently contrasted the evil conditions resulting from capitalism with the moral and economic utopia of socialism." (8)

In 1899 Snowden was elected to the Keightley Town Council and the School Board. He also served as editor of a local socialist newspaper. Snowden continued to travel the country and in 1903 was elected as the national chairman of the Independent Labour Party (ILP). Like Keir Hardie, Snowden was a Christian Socialist, and in 1903 the two men wrote a pamphlet together on their beliefs, The Christ that is to Be. (9)

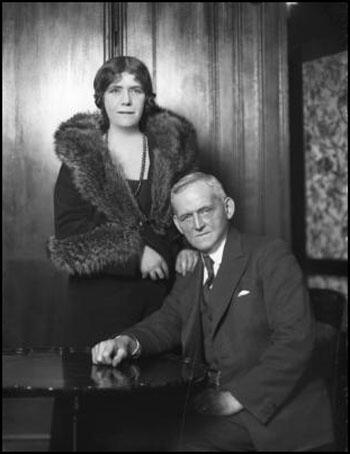

In 1904 Snowden met Ethel Annakin at a Fabian Society meeting in Leeds. Ethel was a schoolteacher who was also a member of the ILP where she met Mary Gawthorpe and Isabella Ford. In 1903 Annakin, Gawthorpe and Ford formed a local branch of the Nation Union of Women's Suffrage Societies. Snowden, who had not previously supported votes for women, was persuaded by Ethel's arguments. (10)

On 13th March 1905 Philip and Ethel married at Otley Register Office. The guests included Isabella Ford and Fred Jowett. Snowden made several attempts to enter the House of Commons. Snowden was defeated at Blackburn in the 1900 General Election. He also failed at the Wakefield by-election in 1902. Snowden was finally successful in the 1906 General Election when he was elected as the Labour MP for Blackburn. Snowden commented that after the declaration of the poll a woman forced herself to his side, and through her tears, joy and hope shone as she said, "Oh, Mr. Snowden, but you will fight for the poor, won't you?" (11)

At the time of her marriage Ethel Snowden was described by the ILP journal, The Labour Leader, as someone who could be compared with Annie Besant: "to her good gifts of dark eyes, golden brown hair and rich colour, Nature has added a sweet singing voice and musical ability of no mean order … she has won the affectionate regard of all those who have come into intimate acquaintance with her by her warm enthusiasm for the cause." (12)

Snowden played an active role in the women's suffrage campaign and joined the Men's League For Women's Suffrage. However, he was totally opposed to the militant campaign of the Women Social & Political Union. "So long as these women confined their activities to such ingenuous performances as tying themselves to street lamps and park railings, throwing leaflets from the Gallery of the House on the heads of members, or getting themselves arrested for causing obstruction, the public were more amused than angry, though the opponents of women suffrage never failed to point to these antics as proof of the unfitness of women to vote. When they began to destroy property and risk the lives of others than themselves the public began to turn against them. The National Union of Woman's Suffrage Societies, whose gallant educational and constitutional work for women's freedom had been carried on for more than fifty years, publicly dissociated themselves from these terrorist activities." (13)

Snowden added to his income by journalism. He wrote a regular column for the Daily Herald. Despite his puritanical background, he was willing to write populist copy. He disagreed with those activists who "regard it as inconsistent with their principles to give prominence to sensational news" (14) One of his critics, Bruce Glasier, commented: "Snowden does nothing but write for money. He has become an extinct volcano. His wife goes to rich parties". (15) James Middleton also disapproved of the way he criticised party leader, Ramsay MacDonald in the press "but does not come to Party meetings and thrash them out with his colleagues first. (16)

Ethel Snowden was also a talented writer. She wrote several pamphlets on the subject of women where she advocated co-operative child-minding and state benefits for mothers. Snowden also wrote two important books on politics, The Woman Socialist (1907) and The Feminist Movement (1913). June Hannam has argued: "She (Snowden) argued that the state should assume major responsibility for the costs of childcare, including state salaries for mothers and advocated co-operative housekeeping and easier divorce. Influenced by the ideas of eugenicists she called for state control of marriage, believing that the mentally ill and those aged under twenty-six should not be able to marry." (17)

During this period Snowden wrote a great deal about his views on Christian Socialism, the Temperance Movement and economics issues. This included The Socialist's Budget (1907), Old Age Pensions (1907), Socialism and the Drink Question (1908), Socialism and Teetotalism (1909) and the Living Wage (1909). In the House of Commons Snowden developed a reputation as an expert on economic issues and advised David Lloyd George on his 1909 People's Budget and other policies introduced by H. H. Asquith's Liberal government. (18) Bruce Glasier commented that Snowden " is under suspicion of having become a mere tuft on the tail of the Liberal party". (19)

First World War

Philip Snowden was a pacifist and refused to support Britain's involvement in the First World War. Philip and Ethel Snowden both joined the Union of Democratic Control (UDC). The UDC soon emerged at the most important of all the anti-war organizations in Britain and by 1915 had 300,000 members. Frederick Pethick-Lawrence explained the objectives of the UDC: "As its name implies, it was founded to insist that foreign policy should in future, equally with home policy, be subject to the popular will. The intention was that no commitments should be entered into without the peoples being fully informed and their approval obtained. By a natural transition, the objects of the Union came to include the formation of terms of a durable settlement, on the basis of which the war might be brought an an end." (20)

After the outbreak of the war two pacifists, Clifford Allen and Fenner Brockway, formed the No-Conscription Fellowship (NCF), an organisation that encouraged men to refuse war service. The NCF required its members to "refuse from conscientious motives to bear arms because they consider human life to be sacred." Philip Snowden became the NCF's chief spokesman in the House of Commons. His principled stance was unpopular with the public, but it helped his political career. He returned to the national council of the Independent Labour Party in 1915 and was its chairman from 1917. He wrote a weekly column for its main journal, The Labour Leader, from 1916 and championed its continuing role in the Labour Party. (21)

1923 Government

As a result of his opposition to the war Snowden was defeated at Blackburn in the 1918 General Election. However, Snowden was eventually forgiven and was elected to represent Colne Valley in the 1922 General Election. In the 1923 General Election, the Labour Party won 191 seats. David Marquand has pointed out that: "The new parliamentary Labour Party was a very different body from the old one. In 1918, 48 Labour M.P.s had been sponsored by trade unions, and only three by the ILP. Now about 100 members belonged to the ILP, while 32 had actually been sponsored by it, as against 85 who had been sponsored by trade unions.... In Parliament, it could present itself for the first time as the movement of opinion rather than of class." (22)

Although the Conservative Party had 258 seats, Herbert Asquith announced that the Liberal Party would not keep the Tories in office. If a Labour Government were ever to be tried in Britain, he declared, "it could hardly be tried under safer conditions". The Daily Mail warned about the dangers of a Labour government and the Daily Herald commented on the "Rothermere press as a frantic attempt to induce Mr Asquith to combine with the Tories to prevent a Labour Government assuming office". (23) John R. Clynes, the former leader of the Labour Party, argued: "Our enemies are not afraid we shall fail in relation to them. They are afraid that we shall succeed." (24)

On 22nd January, 1924 Stanley Baldwin resigned. At midday, the 57 year-old, Ramsay MacDonald went to Buckingham Palace to be appointed prime minister. He later recalled how George V complained about the singing of the Red Flag and the La Marseilles, at the Labour Party meeting in the Albert Hall a few days before. MacDonald apologized but claimed that there would have been a riot if he had tried to stop it. (25)

Robert Smillie, the Labour MP for Morpeth, believed that MacDonald had made a serious mistake in forming a government. "At last we had a Labour Government! I have to tell you that I did not share in that jubilation. In fact, had I had a voice in the matter which, as a mere back-bencher I did not, I would have strongly advised MacDonald not to touch the seals of office with the proverbial barge pole. Indeed, I was very doubtful indeed about the wisdom of forming a Government. Given the arithmetic of the situation, we could not possibly embark on a proper Socialist programme." (26)

G.D.H. Cole pointed out that MacDonald was in a difficult position. If he refused to form a government "it would have been widely misrepresented as showing Labour's fears of its own capacity, and it would have meant leaving the unemployed to their plight and - what weighed even more with many socialists - doing nothing to improve the state of international relations or to further European reconstruction and recovery." Left-wing members of the Labour Party suggested that MacDonald should accept office and invite defeat by putting forward a Socialist programme. The problem with that argument was the party could not financially afford another election, nor would they have been likely to win any more seats in the House of Commons. (27)

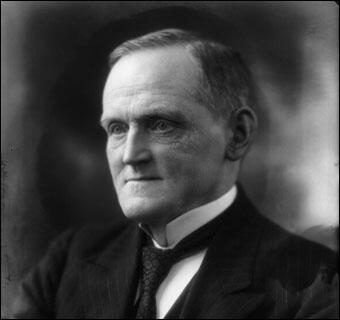

Ramsay MacDonald agreed to head a minority government, and therefore became the first member of the party to become prime minister. He had the problem of forming a Cabinet with colleagues who had little, or no administrative experience. MacDonald's appointments included Philip Snowden as Chancellor of the Exchequer. He took up office in January 1924. According to his biographer, Duncan Tanner: "His policy was cautious but constructive. He argued that progress could be sustained only if industries affected by excessive competition were modernized. A commission on trade and industry was set up to discuss industrial rationalization. Snowden himself stressed the modernization of electricity generation. Land taxation, a little-studied fixation of Snowden's, was planned but not implemented. He reduced expenditure on armaments, cut import duties on various staple foods, and expanded subsidies for building council houses, but shelved the idea of a capital levy. Moderates inside and outside the party welcomed his first budget - a remarkable achievement, given his limited economic training." (28)

John R. Clynes wrote in his Memoirs (1937): "An engine-driver rose to the rank of Colonial Secretary, a starveling clerk became Great Britain's Premier, a foundry-hand was charged to Foreign Secretary, the son of a Keighley weaver was created Chancellor of the Exchequer, one miner became Secretary for War and another Secretary of State for Scotland." (29)

It has been argued that Snowden established a relationship of mutual respect with the leading civil servants. His critics say that he simply adopted their views. One of his opponents in the House of Commons, the Conservative Party MP, Winston Churchill, commented: "We must imagine 'with what joy Mr Snowden was welcomed at the Treasury by the permanent officials... The Treasury mind and the Snowden mind embraced each other with the fervour of two long-separated lizards". (30)

Another one of his political opponents, Frederick Smith, stated: "Honest, visionary, implacable, a theorist in his very inconsistencies, he is a man who has fought a hard battle with life and health and won it - and in doing so has raised himself by his conspicuous courage and abilities to one of the highest places of a State in which he sees so much to disapprove." (31)

1924 General Election

The Daily Mail published the Zinoviev Letter on 25th October 1924, just four days before the 1924 General Election. Under the headline "Civil War Plot by Socialists Masters" it argued: "Moscow issues orders to the British Communists... the British Communists in turn give orders to the Socialist Government, which it tamely and humbly obeys... Now we can see why Mr MacDonald has done obeisance throughout the campaign to the Red Flag with its associations of murder and crime. He is a stalking horse for the Reds as Kerensky was... Everything is to be made ready for a great outbreak of the abominable class war which is civil war of the most savage kind." (32)

Dora Russell, whose husband, Bertrand Russell, was standing for the Labour Party in Chelsea, commented: "The Daily Mail carried the story of the Zinoviev letter. The whole thing was neatly timed to catch the Sunday papers and with polling day following hard on the weekend there was no chance of an effective rebuttal, unless some word came from MacDonald himself, and he was down in his constituency in Wales. Without hesitation I went on the platform and denounced the whole thing as a forgery, deliberately planted on, or by, the Foreign Office to discredit the Prime Minister." (33)

Ramsay MacDonald suggested he was a victim of a political conspiracy: "I am also informed that the Conservative Headquarters had been spreading abroad for some days that... a mine was going to be sprung under our feet, and that the name of Zinoviev was to be associated with mine. Another Guy Fawkes - a new Gunpowder Plot... The letter might have originated anywhere. The staff of the Foreign Office up to the end of the week thought it was authentic... I have not seen the evidence yet. All I say is this, that it is a most suspicious circumstance that a certain newspaper and the headquarters of the Conservative Association seem to have had copies of it at the same time as the Foreign Office, and if that is true how can I avoid the suspicion - I will not say the conclusion - that the whole thing is a political plot?" (34)

Bob Stewart claimed that the letter included several mistakes that made it clear it was a forgery. This included saying that Grigory Zinoviev was not the President of the Presidium of the Communist International. It also described the organisation as the "Third Communist International" whereas it was always called "Third International". Stewart argued that these "were such infantile mistakes that even a cursory examination would have shown the document to be a blatant forgery." (35)

The rest of the Tory owned newspapers ran the story of what became known as the Zinoviev Letter over the next few days and it was no surprise when the election was a disaster for the Labour Party. The Conservatives won 412 seats and formed the next government. Lord Beaverbrook, the owner of the Daily Express and Evening Standard, told Lord Rothermere, the owner of The Daily Mail and The Times, that the "Red Letter" campaign had won the election for the Conservatives. Rothermere replied that it was probably worth a hundred seats. (36)

1929-1931 Government

Until he achieved power Snowden was seen as someone on the left of the Labour Party. However, as Chancellor of the Exchequer, he was criticised for being too conservative. In 1927 Snowden resigned from the Independent Labour Party (ILP), complaining that it was "drifting more and more away from… evolutionary socialism into revolutionary socialism". (37) George Lansbury found him "stiff and difficult" to work with and someone who had lost interest in the idea of "redistributing wealth". (38)

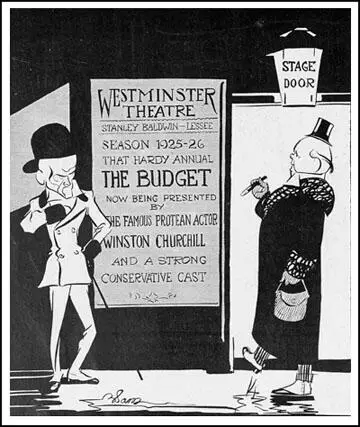

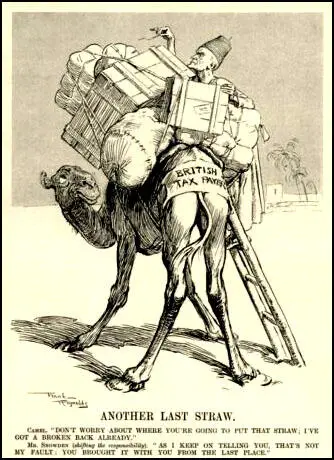

The Bystander (13th May, 1925)

Snowden thought he would make a better leader of the Labour Party than Ramsay MacDonald. He attacked MacDonald's "aloofness" and distance from the party, he claimed to be "expressing the feelings of all my colleagues who have talked with me on this subject". (39) Although these views were widely held, few thought that Snowden would make a good leader. Most of his parliamentary colleagues felt that he was no more approachable than MacDonald. He was now 63 and considered to be too old and MPs tended to prefer the economic ideas of people like Hugh Dalton. (40)

In January 1929, 1,433,000 people in Britain were out of work. Stanley Baldwin was urged to take measures that would protect the depressed iron and steel industry. Baldwin ruled this out owing to the pledge against protection which had been made at the 1924 election. Agriculture was in an even worse condition, and here again the government could offer little assistance without reopening the dangerous tariff issue. Baldwin was considered to be a popular prime minister and he fully expected to win the general election that was to take place on 30th May. (41)

In its manifesto the Conservative Party blamed the General Strike for the country's economic problems. "Trade suffered a severe set-back owing to the General Strike, and the industrial troubles of 1926. In the last two years it has made a remarkable recovery. In the insured industries, other than the coal mining industry, there are now 800,000 more people employed and 125,000 fewer unemployed than when we assumed office... This recovery has been achieved by the combined efforts of our people assisted by the Government's policy of helping industry to help itself. The establishment of stable conditions has given industry confidence and opportunity." (42)

The Labour Party attacked the record of Baldwin's government: "By its inaction during four critical years it has multiplied our difficulties and increased our dangers. Unemployment is more acute than when Labour left office.... The Government's further record is that it has helped its friends by remissions of taxation, whilst it has robbed the funds of the workers' National Health Insurance Societies, reduced Unemployment Benefits, and thrown thousands of workless men and women on to the Poor Law. The Tory Government has added £38,000,000 to indirect taxation, which is an increasing burden on the wage-earners, shop-keepers and lower middle classes." (43)

During the election campaign, David Lloyd George published a pamphlet, We Can Conquer Unemployment. Lloyd George pledged that if his party were returned to office, they would reduce levels of unemployment to normal within one year by utilising the stagnant labour force in vast schemes of national development. Lloyd George proposed a government scheme where 350,000 men were to be employed on road-building, 60,000 on housing, 60,000 on telephone development and 62,000 on electrical development. The cost would be £250 million, but the cumulative effect of all schemes would generate an annual saving of £30 million to the Unemployment Fund. (44)

Lloyd George was attacked by Tory politicians as they feared the proposals would appeal to the public. Neville Chamberlain, the Conservative MP for Ladywood argued that it cost £250 a year to find work for one man and only £60 to keep him in idleness. The government published a White Paper that "would reduce unemployment without bankrupting the nation". Baldwin suggested that "he (Lloyd George) has spent his whole life in platering together the true and the false and therefore manufacturing the plausible". William Joynson-Hicks, the Home Secretary, said he could not "understand how a man of Lloyd George's ability could put such a proposal before the people of this country". (45)

John Maynard Keynes and Hubert Henderson, who had helped Lloyd George to write the pamphlet, replied with another pamphlet, Can Lloyd George Do It? They concluded that it was possible for a government to successively introduce these methods to reduce unemployment. They then went on to satirise Baldwin's approach to the subject: "You must not do anything for that will only mean that you cannot do something else... We will not promise more than we can perform. We therefore promise nothing." (46)

A massive campaign in the Tory press against the proposal of increased public spending was very successful. In the 1929 General Election the Conservatives won 8,656,000 votes (38%), the Labour Party 8,309,000 (37%) and the Liberals 5,309,000 (23%). However, the bias of the system worked in Labour's favour, and in the House of Commons the party won 287 seats, the Conservatives 261 and the Liberals 59.

A. J. P. Taylor has argued that the idea of increasing public spending would be good for the economy, was difficult to grasp. "It seemed common sense that a reduction in taxes made the taxpayer richer... Again it was accepted doctrine that British exports lagged because costs of production were too high; and high taxation was blamed for this about as much as high wages." (47) John Maynard Keynes later commented: "The difficulty lies, not in the new ideas, but in escaping from the old ones, which ramify, for those brought up as most of us have been, into every corner of our minds." (48)

Philip Snowden was once again appointed as Chancellor of the Exchequer. In January 1930 unemployment in Britain reached 1,533,000. By March, the figure was 1,731,000. Oswald Mosley proposed a programme that he believed would help deal with the growing problem of unemployment in Britain. According to David Marquand: "It made three main assertions - that the machinery of government should be drastically overhauled, that unemployment could be radically reduced by a public-works programme on the lines advocated by Keynes and the Liberal Party, and that long-term economic reconstruction required a mobilisation of national resources on a larger scale than has yet been contemplated. The existing administrative structure, Mosley argued, was hopelessly inadequate. What was needed was a new department, under the direct control of the prime minister, consisting of an executive committee of ministers and a secretariat of civil servants, assisted by a permanent staff of economists and an advisory council of outside experts." (49)

Philip Snowden was a strong believer in laissez-faire economics and disliked the proposals. (50) MacDonald had doubts about Snowden's "hard dogmatism exposed in words and tones as hard as the ideas" but he also dismissed "all the humbug of curing unemployment by Exchequer grants." (51) MacDonald passed the Mosley Memorandum to a committee consisting of Snowden, Tom Shaw, Arthur Greenwood and Margaret Bondfield. The committee reported back on 1st May. Mosley's administrative proposals, the committee claimed "cut at the root of the individual responsibilities of Ministers, the special responsibility of the Chancellor of the Exchequer in the sphere of finance, and the collective responsibility of the Cabinet to Parliament". The Snowden Report went onto argue that state action to reduce unemployment was highly dangerous. To go further than current government policy "would be to plunge the country into ruin". (52)

MacDonald recorded in his diary what happened when Oswald Mosley heard the news about his proposals being rejected. "Mosley came to see me... had to see me urgently: informed me he was to resign. I reasoned with him and got him to hold his decision over till we had further conversations. Went down to Cabinet Room late for meeting. Soon in difficulties. Mosley would get away from practical work into speculative experiments. Very bad impression. Thomas light, inconsistent but pushful and resourceful; others overwhelmed and Mosley on the verge of being offensively vain in himself." (53)

Mosley was not trusted by most of his fellow MPs. He came from an aristocratic background and first entered the House of Commons as a representative of the Conservative Party. One Labour Party MP said Mosley had a habit of speaking to his colleagues "as though he were a feudal landlord abusing tenants who are in arrears with their rent". (54) John Bew described Mosley as "handsome... lithe and black and shiny... he looked like a panther but behaved like a hyena". (55)

At a meeting of Labour MPs took place on 21st May, Oswald Mosley outlined his proposals. This included the provision of old-age pensions at sixty, the raising of the school-leaving age and an expansion in the road programme. He gained support from George Lansbury and Tom Johnson, but Arthur Henderson, speaking on behalf of MacDonald, appealed to Mosley to withdraw his motion so that his proposals could be discussed in detail at later meetings. Mosley insisted on putting his motion to the vote and was beaten by 210 to 29. (56)

Philip Snowden was once again appointed as Chancellor of the Exchequer. In January 1930 unemployment in Britain reached 1,533,000. By March, the figure was 1,731,000. Oswald Mosley proposed a programme that he believed would help deal with the growing problem of unemployment in Britain. According to David Marquand: "It made three main assertions - that the machinery of government should be drastically overhauled, that unemployment could be radically reduced by a public-works programme on the lines advocated by Keynes and the Liberal Party, and that long-term economic reconstruction required a mobilisation of national resources on a larger scale than has yet been contemplated. The existing administrative structure, Mosley argued, was hopelessly inadequate. What was needed was a new department, under the direct control of the prime minister, consisting of an executive committee of ministers and a secretariat of civil servants, assisted by a permanent staff of economists and an advisory council of outside experts." (49)

Philip Snowden, was a strong believer in laissez-faire economics and disliked the proposals. (50) MacDonald had doubts about Snowden's "hard dogmatism exposed in words and tones as hard as the ideas" but he also dismissed "all the humbug of curing unemployment by Exchequer grants." (51) MacDonald passed the Mosley Memorandum to a committee consisting of Snowden, Tom Shaw, Arthur Greenwood and Margaret Bondfield. The committee reported back on 1st May. Mosley's administrative proposals, the committee claimed "cut at the root of the individual responsibilities of Ministers, the special responsibility of the Chancellor of the Exchequer in the sphere of finance, and the collective responsibility of the Cabinet to Parliament". The Snowden Report went onto argue that state action to reduce unemployment was highly dangerous. To go further than current government policy "would be to plunge the country into ruin". (52)

MacDonald recorded in his diary what happened when Oswald Mosley heard the news about his proposals being rejected. "Mosley came to see me... had to see me urgently: informed me he was to resign. I reasoned with him and got him to hold his decision over till we had further conversations. Went down to Cabinet Room late for meeting. Soon in difficulties. Mosley would get away from practical work into speculative experiments. Very bad impression. Thomas light, inconsistent but pushful and resourceful; others overwhelmed and Mosley on the verge of being offensively vain in himself." (53)

Mosley was not trusted by most of his fellow MPs. He came from an aristocratic background and first entered the House of Commons as a representative of the Conservative Party. One Labour Party MP said Mosley had a habit of speaking to his colleagues "as though he were a feudal landlord abusing tenants who are in arrears with their rent". (54) John Bew described Mosley as "handsome... lithe and black and shiny... he looked like a panther but behaved like a hyena". (55)

At a meeting of Labour MPs took place on 21st May, Oswald Mosley outlined his proposals. This included the provision of old-age pensions at sixty, the raising of the school-leaving age and an expansion in the road programme. He gained support from George Lansbury and Tom Johnson, but Arthur Henderson, speaking on behalf of MacDonald, appealed to Mosley to withdraw his motion so that his proposals could be discussed in detail at later meetings. Mosley insisted on putting his motion to the vote and was beaten by 210 to 29. (56)

Mosley now resigned from the government and was replaced by Clement Attlee. It has been claimed that MacDonald was so fed up with Mosley that he looked around him and choose the "most uninteresting, unimaginative but most reliable among his backbenchers to replace the fallen angel". Winston Churchill said he was "a modest little man, with plenty to be modest about". Mosley was more generous as he accepted that he had "a clear, incisive and honest mind within the limits of his range". However, he added, in agreeing to take his job, Attlee "must be reckoned as content to join a government visibly breaking the pledges on which he was elected." (57)

In a debate in the House of Commons on 28th May 1930, MacDonald argued that the rise in unemployment was caused by factors outside the government's control. The following month unemployment in Britain was 1,946,000 and by the end of the year it reached a staggering 2,725,000. MacDonald responded to the crisis by asking John Maynard Keynes to become a chairman of the Economic Advisory Council to "advise His Majesty's Government in economic matters". Members of the committee included J. A. Hobson, George Douglas Cole, Walter Citrine, Hubert Henderson, Hugh Macmillan, Walter Layton, William Weir and Andrew Rae Duncan. However, Keynes was disappointed by MacDonald's reaction to his advice: "Politicians rarely look to economists to tell them what to do: mainly to give them arguments for doing things they want to do, or for not doing things they don't want to do." (58)

Cole later recalled: "Philip Snowden held a strong position in the Party as its one recognised financial expert... MacDonald nor most of the other members of the Cabinet had any understanding of finance, or even thought they had... The Economic Advisory Council, of which I was a member, discussed the situation again and again; and some of us, including Keynes, tried to get MacDonald to understand the sheer necessity of adopting some definite policy for stopping the rot. Snowden was inflexible; and MacDonald could not make up his mind, with the consequence that Great Britain drifted steadily towards a disaster." (59)

MacDonald did give approval for several public-works projects. By June 1930 the projects were valued at £44 million. Vernon Hartshorn, who had been put in charge of these projects, estimated that the total number employed directly and indirectly as a result of this investment, would be about 150,000. The prime minister admitted in his diary on 24th June that this was not enough: "Unemployment is baffling us for the moment. Up 110,000 in a fortnight. Nothing can dam the flow at the moment." (60)

John Maynard Keynes wrote several articles for The Nation on the economic crisis. On 13th December he praised the manifesto published by Oswald Mosley and signed by seventeen Labour Party MPs as "offering a starting point for thought and action". The following week he asked: "Is the man in the street now awakening from a pleasant dream to face the darkness of facts? Or dropping off into a nightmare that will pass away?" He then answered his own question: "This is not a dream. This is a nightmare. For the resources of nature and men's devices are just as fertile and productive as they ever were." (61)

Philip Snowden wrote in his notebook on 14th August that "the trade of the world has come near to collapse and nothing we can do will stop the increase in unemployment." He was growing increasingly concerned about the impact of the increase in public-spending. At a cabinet meeting in January 1931, he estimated that the budget deficit for 1930-31 would be £40 million. Snowden argued that it might be necessary to cut unemployment benefit. Margaret Bondfield looked into this suggestion and claimed that the government could save £6 million a year if they cut benefit rates by 2s. a week and to restrict the benefit rights of married women, seasonal workers and short-time workers. (62)

Unemployment continued to rise and the national fund was now in deficit. Austen Morgan, has argued that when Ramsay MacDonald refused to become master of events, they began to take control of the Labour government: "With the unemployed the principal sufferers of the world recession, he allowed middle-class opinion to target unemployment benefit as a problem... With Snowden at the Treasury, it was only a matter of time before the economic issue was being defined as an unbalanced budget." (63)

The George May Report

In February 1931, on the advice of Philip Snowden, MacDonald asked George May, the Secretary of the Prudential Assurance Company, to form a committee to look into Britain's economic problems. Other members of the committee included Arthur Pugh (trade unionist), Charles Latham (trade unionist), Patrick Ashley Cooper (Governor of the Hudson's Bay Company), Mark Webster Jenkinson (Vickers Armstrong Shipbuilders), William Plender (President of the Institute of Chartered Accountants) and Thomas Royden (Thomas Royden & Sons Shipping Company). (64)

A. J. P. Taylor has pointed out that four of the May Committee were leading capitalists, whereas only two represented the labour movement: "Snowden calculated that a fearsome report from this committee would terrify Labour into accepting economy, and the Conservatives into accepting increased taxation. Meanwhile he produced a stop-gap budget in April, intending to produce a second, more severe budget in the autumn." Snowden made speeches in favour of "national unity" hoping that he would get help from the other political parties to push through harsh measures. (65)

Fenner Brockway claimed that in June, 1931, he heard that MacDonald was "entering into secret conversations with representatives of of the Conservative and Liberal Parties to scuttle the Labour Government and to form a National Government." Brockway wrote an article about this in the Labour Leader. The charge was denied by Arthur Henderson, the Foreign Secretary, but not by MacDonald and Snowden. "Later we learned that MacDonald and Snowden had been conferring without the knowledge of their Cabinet colleagues." (66)

Snowden came increasing under attack from England's leading economists. John Maynard Keynes criticised Snowden's belief in free-trade and urged the introduction of an import tax in order that Britain might resume the vacant financial leadership of the world, which no one else had the experience or the public spirit to occupy. Keynes believed this measure would create a budget surplus. (67) Others questioned the wisdom of devoting £60m to paying off the national debt. (68)

On 14th July, the Economic Advisory Council published its report on the state of the economy. Chaired by Hugh Macmillan, committee members included John Maynard Keynes, J. A. Hobson, George Douglas Cole, Walter Citrine, Hubert Henderson, Walter Layton, William Weir and Andrew Rae Duncan. The report drew attention to Britain's balance of payments. "The export of manufactured goods had not paid for the import of food and raw materials for over a hundred years but this had been made up by so-called 'invisible' earnings, such as banking, shipping and the interest on foreign income. These had declined with the recession. Crude estimates a new economic indicator - suggested that Britain was about enter into a balance of payments deficit... By way of solution, they proposed a revenue tariff." (69)

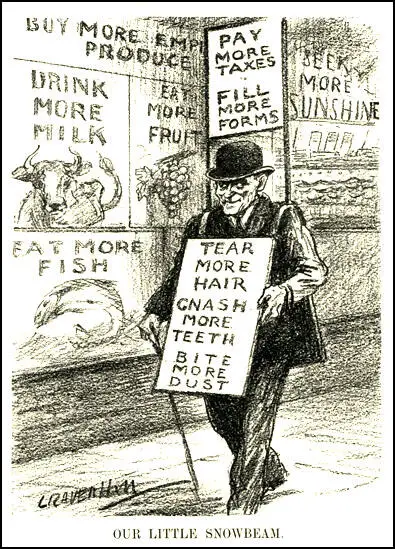

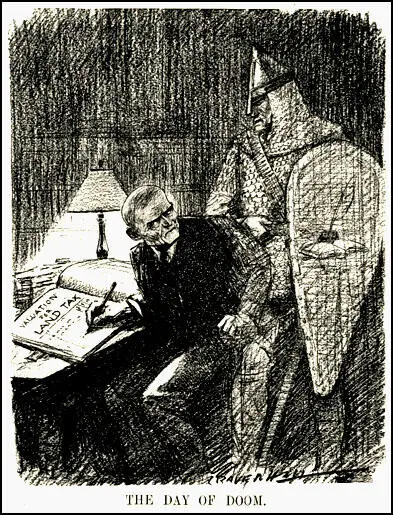

Philip Snowden: "Yes, and it is not such a soft job as yours. You were not troubled with by-elections.

Leonard Raven-Hill, The Day of Doom (17th June, 1931)

The George May Committee produced (the two trade unionists refused to sign the document) its report that presented a picture of Great Britain on the verge of financial disaster. It proposed cutting £96,000,000 off the national expenditure. Of this total £66,500,000 was to be saved by cutting unemployment benefits by 20 per cent and imposing a means test on applicants for transitional benefit. Another £13,000,000 was to be saved by cutting teachers' salaries and grants in aid of them, another £3,500,000 by cutting service and police pay, another £8,000,000 by reducing public works expenditure for the maintenance of employment. "Apart from the direct effects of these proposed cuts, they would of course have given the signal for a general campaign to reduce wages; and this was doubtless a part of the Committee's intention." (70)

The five rich men on the committee recommended, not surprisingly, that only £24 million of this deficit should be met by increased taxation. As David W. Howell has pointed out: "A committee majority of actuaries, accountants, and bankers produced a report urging drastic economies; Latham and Pugh wrote a minority report that largely reflected the thinking of the TUC and its research department. Although they accepted the majority's contentious estimate of the budget deficit as £120 million and endorsed some economies, they considered the underlying economic difficulties not to be the result of excessive public expenditure, but of post-war deflation, the return to the gold standard, and the fall in world prices. An equitable solution should include taxation of holders of fixed-interest securities who had benefited from the fall in prices." (71)

William Ashworth, the author of An Economic History of England 1870-1939 (1960) has argued: "The report presented an overdrawn picture of the existing financial position; its diagnosis of the causes underlying it was inaccurate; and many of its proposals (including the biggest of them) were not only harsh but were likely to make the economic situation worse, not better." (72) Keynes reacted with great anger as it was the complete opposite of what he had been telling the government to do and called the May Report "the most foolish document I ever had the misfortune to read". (73)

The May Report had been intended to be used as a weapon to use against those Labour MPs calling for increased public expenditure. What it did in fact was to create abroad a belief in the insolvency of Britain and in the insecurity of the British currency, and thus to start a run on sterling, vast amounts of which were held by foreigners who had exchanged their own currencies for it in the belief that it was "as good as gold". This foreign-owned sterling was now exchanged into gold or dollars and soon began to threaten the stability of the pound. (74)

The Labour government officially rejected the report because MacDonald and Snowden could not persuade their Cabinet colleagues to accept May's recommendations. MacDonald and Snowden now formed a small committee, made up of themselves and Arthur Henderson, Jimmy Thomas and William Graham, three people they thought they could persuade to accept public spending cuts. Their report was published on 31st July, the last day of parliament sitting. It was a bland document that made no statement on May's recommendations. (75)

On 5th August, John Maynard Keynes wrote to Ramsay MacDonald, arguing that the committee's recommendations clearly represented "an effort to make the existing deflation effective by bringing incomes down to the level of prices" and if adopted in isolation, they would result in "a most gross perversion of social justice". Keynes suggested that the best way to deal with the crisis was to leave the gold standard and devalue sterling. (76)

Philip Snowden presented his recommendations to the Cabinet on 20th August. It included the plan to raise approximately £90 million from increased taxation and to cut expenditure by £99 million. £67 million was to come from unemployment insurance, £12 million from education and the rest from the armed services, roads and a variety of smaller programmes. Most members of the Cabinet rejected the idea of the proposed cut in unemployment benefit and the meeting ended without any decisions being made. Clement Attlee, who was a supporter of Keynes, condemned Snowden for his "misplaced fidelity to laissez-faire economics". (77)

Frederick Pethick-Lawrence and Susan Lawrence both decided to resign from the government if the cuts to the unemployment benefit went ahead: Pethick-Lawrence wrote: "Susan Lawrence came to see me. As Parliamentary Secretary to the Ministry of Health, she was concerned with the proposed cuts in unemployment relief, which she regarded as dreadful. We discussed the whole situation and agreed that, if the Cabinet decided to accept the cuts in their entirety, we would both resign from the Government." (78)

Arthur Henderson argued that rather do what the bankers wanted, Labour should had over responsibility to the Conservatives and Liberals and leave office as a united party. The following day MacDonald and Snowden had a private meeting with Neville Chamberlain, Samuel Hoare, Herbert Samuel and Donald MacLean to discuss the plans to cut government expenditure. Chamberlain argued against the increase in taxation and called for further cuts in unemployment benefit. MacDonald also had meetings with trade union leaders, including Walter Citrine and Ernest Bevin. They made it clear they would resist any attempts to put "new burdens on the unemployed". Sidney Webb later told his wife Beatrice Webb that the trade union leaders were "pigs" as they "won't agree to any cuts of unemployment insurance benefits or salaries or wages". (79)

At another meeting on 23rd August, 1931, nine members (Arthur Henderson, George Lansbury, John R. Clynes, William Graham, Albert Alexander, Arthur Greenwood, Tom Johnson, William Adamson and Christopher Addison) of the Cabinet stated that they would resign rather than accept the unemployment cuts. A. J. P. Taylor has argued: "The other eleven were presumably ready to go along with MacDonald. Six of these had a middle-class or upper-class background; of the minority only one (Addison)... Clearly the government could not go on. Nine members were too many to lose." (80)

That night MacDonald went to see George V about the economic crisis. He warned the King that several Cabinet ministers were likely to resign if he tried to cut unemployment benefit. MacDonald wrote in his diary: "King most friendly and expressed thanks and confidence. I then reported situation and at end I told him that after tonight I might be of no further use, and should resign with the whole Cabinet.... He said that he believed I was the only person who could carry the country through." (81)

MacDonald told his son, Malcolm MacDonald, about what happened at the meeting: "The King has implored J.R.M. to form a National Government. Baldwin and Samuel are both willing to serve under him. This Government would last about five weeks, to tide over the crisis. It would be the end, in his own opinion, of J.R.M.'s political career. (Though personally I think he would come back after two or three years, though never again to the Premiership. This is an awful decision for the P.M. to make. To break so with the Labour Party would be painful in the extreme. Yet J.R.M. knows what the country needs and wants in this crisis, and it is a question whether it is not his duty to form a Government representative of all three parties to tide over a few weeks, till the danger of financial crash is past - and damn the consequences to himself after that." (82)

After another Cabinet meeting where no agreement about how to deal with the economic crisis could be achieved, Ramsay MacDonald went to Buckingham Palace to resign. Sir Clive Wigram, the King's private secretary, later recalled that George V "impressed upon the Prime Minister that he was the only man to lead the country through the crisis and hoped that he would reconsider the situation." At a meeting with Stanley Baldwin, Neville Chamberlain and Herbert Samuel, MacDonald told them that if he joined a National Government it "meant his death warrant". According to Chamberlain he said "he would be a ridiculous figure unable to command support and would bring odium on us as well as himself." (83)

The National Government

On 24th August 1931 Ramsay MacDonald returned to the palace and told the King that he had the Cabinet's resignation in his pocket. The King replied that he hoped that MacDonald "would help in the formation of a National Government." He added that by "remaining at his post, his position and reputation would be much more enhanced than if he surrendered the Government of the country at such a crisis." Eventually, he agreed to form a National Government. Later that day the King had a meeting with the leaders of the Conservative and Liberal parties. Herbert Samuel later recorded that he told the king that MacDonald should be maintained in office "in view of the fact that the necessary economies would prove most unpalatable to the working class". He added that MacDonald was "the ruling class's ideal candidate for imposing a balanced budget at the expense of the working class." (84)

Later that day MacDonald returned to the palace and had another meeting with the King. MacDonald told the King that he had the Cabinet's resignation in his pocket. The King replied that he hoped that MacDonald "would help in the formation of a National Government." He added that by "remaining at his post, his position and reputation would be much more enhanced than if he surrendered the Government of the country at such a crisis." Eventually, he agreed to continue to serve as Prime Minister. George V congratulated all three men "for ensuring that the country would not be left governless." (85)

Ramsay MacDonald was only able to persuade three other members of the Labour Party to serve in the National Government: Philip Snowden (Chancellor of the Exchequer) Jimmy Thomas (Colonial Secretary) and John Sankey (Lord Chancellor). The Conservatives had four places and the Liberals two: Stanley Baldwin (Lord President), Samuel Hoare (Secretary for India), Neville Chamberlain (Minister of Health), Herbert Samuel (Home Secretary), Lord Reading (Foreign Secretary) and Philip Cunliffe-Lister (President of the Board of Trade). (86)

Beatrice Webb wrote in her diary: "Just heard over the wireless what I wished to hear, the the Cabinet as a whole has resigned, J.R.M. accepting office as Prime Minister in order to form a National Emergency government including Tories and Liberals; it being also stated that Snowden, Thomas and alas! Sankey will take office under him. I regret Sankey, but I am glad the other three will disappear from the Labour world; they were rotten stuff... A startling sensation it will be for those faithful followers throughout the country who were unaware of J.R.M.'s and Snowden's gradual conversation to the outlook of the City and London society... So ends, ingloriously, the Labour Cabinet of 1929-1931. (87)

MacDonald's former cabinet colleagues were furious about what he had done. Clement Attlee asked why the workers and the unemployed were to bear the brunt again and not those who sat on profits and grew rich on investments? He complained that MacDonald was a man who had "shed every tag of political convictions he ever had". His so-called National Government was a "shop-soiled pack of cards shuffled and reshuffled". This was "the greatest betrayal in the political history of this country". (88)

The Labour Party's governing national executive, the general council of the TUC and the parliamentary party's consultative committee met and issued a joint manifesto, which declared that the new National Government was "determined to attack the standard of living of the workers in order to meet a situation caused by a policy pursued by private banking interests in the control of which the party has no part." (89)

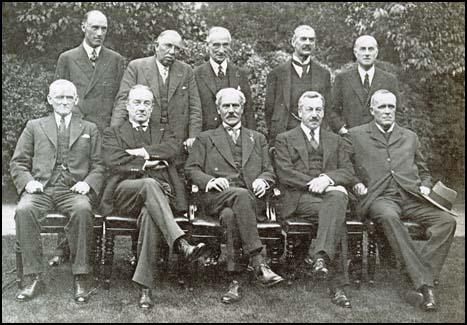

Lord Reading, Neville Chamberlain, Samuel Hoare. Seated, left to right: Philip Snowden,

Stanley Baldwin, Ramsay MacDonald, Herbert Samuel and John Sankey.

Some members of the Labour Party were pleased by the formation of the National Government. Morgan Philips Price commented: "I found Members delighted that Ramsay Macdonald, Philip Snowden and J. H. Thomas had severed themselves from us by their action. We had got rid of the Right Wing without any effort on our part. No one trusted Mr Thomas and Philip Snowden was recognized to be a nineteenth-century Liberal with no longer any place amongst us. State action to remedy the economic crisis was anathema to him. As for Ramsay Macdonald, he was obviously losing his grip on affairs. He had no background of knowledge of economic and financial questions and was hopelessly at sea in a crisis like this. But many, if not most, of the Labour M.P.s thought that at an election we should win hands down." (90)

The Labour Party was appalled by what they considered to be MacDonald's act of treachery. Arthur Henderson commented that MacDonald had never looked into the faces of those who had made it possible for him to be Prime Minister. His close friend, Mary Hamilton, wrote on 28th August: "But greatly as I admire your courage, and ready as I am to believe your gesture may have saved us all, I could not, as I thought the whole situation out on my long journey home, find it possible to support this Government or believe in its policy. It is a very hard decision to make; and this afternoon's party meeting does not make it agreeable to act on - but, there it is. I felt I must write this line to express the deep regret I feel about this, temporary severance between you and the party." (91)

Ramsay MacDonald replied: "Whether you believe it or not, I have saved you, whatever the cost may be to me, but you are all quietly going on drafting manifestoes, talking about opposing cuts in unemployment pay and so on, because I faced the facts a week ago and damned the consequences... If I had agreed to stay in, defied the bankers and a perfect torrent of credit that had been leaving the country day by day, you would all have been overwhelmed and the day you met Parliament you would have been swept out of existence... Still I have always said that the rank and file have not always the same duty as the leaders, and I am willing to apply that now. I dare say you know, however, that for some time I have been very disturbed by the drift in the mind of the Party. I am afraid I am not a machine-made politician, and never will be, and it is far better for me to drop out before it will be impossible for me to make a decent living whilst out of public life." (92)

On 8th September 1931, the National Government's programme of £70 million economy programme was debated in the House of Commons. This included a £13 million cut in unemployment benefit. All those paid by the state, from cabinet ministers and judges down to the armed services and the unemployed, were cut 10 per cent. Teachers, however, were treated as a special case, lost 15 per cent. Tom Johnson, who wound up the debate for the Labour Party, declared that these policies were "not of a National Government but of a Wall Street Government". In the end the Government won by 309 votes to 249. (93)

John Maynard Keynes spoke out against the morality of cutting benefits and public sector pay. He claimed that the plans to reduce the spending on "housing, roads, telephone expansion" was "simply insane". Keynes went on to say the government had been ignoring his advice: "During the last 12 years I have had very little influence, if any, on policy. But in the role of Cassandra, I have had considerable success as a prophet. I declare to you, and I will stake on it any reputation I have, that we have been making in the last few weeks as dreadful errors of policy as deluded statesmen have ever been guilty of." (94)

The cuts in public expenditure did not satisfy the markets. The withdrawals of gold and foreign exchange continued. John Maynard Keynes published an article in the Evening Standard on 10th September, urging import controls and the leaving of the Gold Standard. (95) Two days later he argued in the New Statesman that the government policy "can only delay, it cannot prevent, a recurrence of another crisis similar to that through which we have just passed." (96)

A mutiny of naval ratings at Invergordon on 16th September, led to another run on the pound. That day the Bank of England lost £5 million in defending the currency. This was followed by losing over 10 million on 17th and over 16 million on the 18th. The governor of the Bank of England told the government that it had lost most of its original gold and foreign exchange. On the 20th September, the Cabinet agreed to leave the Gold Standard, something that Keynes had been telling the government to do for several years. (97)

The pound sterling was allowed to float in the international markets and was to fall by more than a quarter. Therefore, devaluation, which the Labour government had destroyed itself in its resistance to this policy, came four weeks after the formation on the National government. The advice of the Bank of England, which had been taken as absolute gospel, was proved to be worthless. Sidney Webb, the former Secretary of State for the Colonies in MacDonald's government, commented: "Nobody told us we could do this." (98)

Ramsay MacDonald still feared for the future, he wrote to a friend that "although we cannot say it in public, the unsettlement regarding sterling and the uncertainty regarding the position of the Government may, at any moment, bring a new crisis, the results of which may well be starvation for great sections of our people, ruin to everybody except a lot of dastardly profiteers and speculators, and the end of our influence in the world." (99)

On 26th September, the Labour Party National Executive decided to expel all Labour Party MPs who had supported the National Government budget, including Philip Snowden, Ramsay MacDonald, Jimmy Thomas, John Sankey. Malcolm MacDonald, William Jowitt, George Gillett, Ernest Bennett, Holford Knight, James Lovat-Fraser, Craigie Aitchison, Samuel Rosbotham, Archibald Church, Richard Denman, Frank Markham and Derwent Hall Caine. As David Marquand has pointed out: "In the circumstances, its decision was understandable, perhaps inevitable. The Labour movement had been built on the trade-union ethic of loyalty to majority decisions. MacDonald had defied that ethic; to many Labour activists, he was now a kind of political blackleg, who deserved to be treated accordingly." (100)

House of Lords

The 1931 General Election was held on 27th October, 1931. MacDonald led an anti-Labour alliance made up of Conservatives and National Liberals. It was a disaster for the Labour Party with several leading Labour figures, including Arthur Henderson, John R. Clynes, Arthur Greenwood, Charles Trevelyan, Herbert Morrison, Emanuel Shinwell, Frederick Pethick-Lawrence, Hastings Lees-Smith, Hugh Dalton, Susan Lawrence, William Wedgwood Benn, Tom Shaw and Margaret Bondfield losing their seats.

Beatrice Webb wrote: "MacDonald... had been aided and abetted with acid malignity by Philip Snowden... The Parliamentary Labour Party had not been defeated but annihilated, largely, we think, by the women's vote... Whether new leaders will spring up with sufficient faith, will-power and knowledge to break through the tough and massive defence of British profit-making capitalism... I cannot foresee...What undid the two Labour governments was not merely their lack of knowledge and the will to apply what knowledge they had, but also their acceptance, as individuals, of the way of life of men of property and men of rank. It is a hard saying and one that condemns ourselves as well as others of the Labour government. You cannot engineer an equalitarian state if you yourself are enjoying the pomp and circumstances of the city of the rich surrounded by the city of the poor." (101)

Philip Snowden did not stand in the 1931 General Election but did take part in the campaign. Snowden contributed a bitter election broadcast, which attacked his old colleagues and described Labour's new policy as "Bolshevism run mad". He also attacked Labour's "capitulation" to the TUC during the crisis, and his colleagues' "dishonest" accounts of cabinet discussions during this period. In November 1931 he was appointed to the House of Lords. (102)

In retirement Snowden turned on Ramsay MacDonald. Discussing MacDonald's repudiation of land taxation following pressure from Conservatives in the government. He pointed out the "nauseating hypocrisy" of MacDonald's comments, continuing "there is no humiliation to which he will not submit if they only will allow him still to be called Prime Minister". (103) He also claimed that MacDonald's unemployment policy suggested that "the unemployed may be dealt with by teaching men… to make mats out of bits of old rope for a few pence". (104)

The attack on MacDonald was intensified in Snowden's An Autobiography (1934). Snowden claimed that MacDonald had consciously misled his cabinet in 1931; that he formed the National Government with unnecessary haste because he found the Tories politically and socially more congenial. He also claimed that following the formation of the National Government, MacDonald "gleefully" rubbed his hands together, commenting "tomorrow every duchess in London will want to kiss me". (105)

In 1935 Snowden advised voters to support the Liberal Party, where it put forward a candidate. He supported David Lloyd George in his campaign for policies similar to those being implemented by Franklin D. Roosevelt. As Duncan Tanner has pointed out: "Lloyd George's ‘new deal' was an updated version of the Keynesian proposals advanced by the Liberals, and derided by Snowden, in 1929. (106) Snowden explained his enthusiasm for this programme as a return to his long-standing economic principles. (107)

Philip Snowden died of a heart-attack on 15th May, 1937, at his home, Eden Lodge, Tilford in Surrey, and was cremated at Woking. He left £3,366. 13s. 11d. to his widow, Ethel Snowden. (108)

Primary Sources

(1) In his book An Autobiography, Philip Snowden described what Cowling was like in the 1860s.

The industrial revolution was late in penetrating this parish. It was not until about twenty years before my birth that handloom weaving disappeared. In my boyhood all the older people had been handloom weavers. The industry had been carried on mainly in the cottages in which the families lived. It was quite common thing for the bedroom of the cottage to contain five or six handlooms, and in this room the weaving was done; and in this room the whole family, which was often very large, had to sleep.

(2) Philip Snowden's father was a Chartist in the 1840s.

I have heard my father relate how a number of handloom weavers contributed a halfpenny a week to buy a copy of the weekly Leeds Mercury, which was then sevenpence, and with these coppers he was sent to a village four miles away each week to get the paper; and then the subscribers to this newspaper met in a cottage and he read the news to them.

The Leeds Mercury in those days was a Radical journal. Those were times of great political and social excitement. The Chartist movement was affecting the industrial population, and the agitation was affecting the industrial population, and the agitation for the Repeal of the Corn Laws was at its height. They were dangerous times for those known to harbour Radical opinions. Throughout the West Riding, as well as other parts of England, men were being arrested and sentenced to long terms of imprisonment for alleged sedition and political conspiracy.

This group of Radical-Chartists in Cowling had to take precautions against the attentions of the constable, and when they gathered together to discuss politics and hear my father read the paper for them they shuttered the window and sometimes placed a scout outside to watch for the constable.

(3) As a child Philip Snowden signed the pledge that he would never drink alcohol.

The vicar of the parish was the Reverend George Bayldon. He was the vicar of the parish for forty years. The only active part he took in the life of the village was in connection with the Temperance Movement. He was the man to whom the boys went when they wanted "to sign teetotal". Mr. Bayldon was the only person in the village who took a daily newspaper, and when the boys wanted paper for their kites it was to Mr. Bayldon they went on the pretext of signing teetotal, but really to beg for old newspapers.

(4) Philip Snowden, An Autobiography (1934)

After the passing of Mr. Forster's Education Act, a few progressive persons in the village started an agitation for the adoption of the Act. The Act was adopted, and the school I attended was taken over by the newly formed School Board. Steps were taken at once to build new school premises. A trained master was appointed, and a new era in child education in the village was opened up. I was between ten and eleven years old when this change took place. It brought me into a new world of learning. We were taught in a new schoolroom, which by comparison with the dingy old place we left seemed like a palace to us. The walls were covered with maps and pictures. Our curriculum was extended to include grammar, geography, history, elementary mathematics, and the simple sciences. We were not troubled with the religious question, for, in order to avoid all controversy, the Board from the beginning banished the Bible from the school, not because they were irreligious, but because they believed that the teaching of religion was best carried out by the sects in their own Sunday Schools.

(5) Philip Snowden, An Autobiography (1934)

In my youth there still survived a few men who had been leaders in the Chartist movement. One of these was George Lomax, a Manchester man, who was a very popular Temperance and Radical speaker. I often heard him. As a young man he had been an eye-witness of the massacre of Peterloo. I heard him tell the story, and he finished a graphic description of the affair by saying: "As I saw the cavalry striking down unarmed and peaceful people I swore eternal enmity to Toryism and all its ways."

Another of the Chartist leaders I heard was Thomas Cooper, who had been a prominent figure in the movement in the forties. He was a very old man when I heard him. He had gone quite blind. His hair fell upon his shoulders, and he looked a patriarchal figure.

(6) Philip Snowden, An Autobiography (1934)

The Trades Unions were very dissatisfied with the attitude of the Liberal Government to the legal position of Trade Unionism. In 1869, at the instigation of John Stuart Mill, an organisation was formed under the name of the Labour Representation League to carry out a national campaign to secure the return of working men to Parliament. It does not appear to have been the intention of this League to form a party which could be permanently in opposition to the Liberal Party. Mills' idea was that, if the working classes put forward working-men candidates and threatened the Liberal majority, the Liberals would be glad to come to terms and provide opportunities for the return of working men. After the election of 1874 the League placed twelve working men in the field, and of these Thomas Burt and Alexander MacDonald were elected at Morpeth and Stafford respectively.

(7) Philip Snowden, An Autobiography (1934)

By the end of 1892 it was felt that the various Labour Unions should be merged into a National Party. So steps were taken to call a Conference, which met at Bradford in January 1893. To this Conference delegates from the local unions, the Fabian Society (which at the time was doing considerable propaganda work among the Radical Clubs), and the Social Democratic Federation, were invited. There were 115 delegates present at this conference, and among them was Mr. George Bernard Shaw, representing the Fabian Society. He played a conspicuous part in the Conference. Mr. Keir Hardie, fresh from his success at West Ham, was elected Chairman of the Conference.

(8) Philip Snowden, An Autobiography (1934)

I brought and carefully studied, among other works, Hyndman's England for All and his Historical Basis of Socialism, which he claimed were the first works on scientific socialism published in English. They were based on Marx's Capital. I did not find these books so interesting and instructive as other volumes on the subject which I read. I derived much help and information from the Fabian Essays and the Fabian Tracts, and from the books of Edward Carpenter - England's Ideal and Civilisation, its Causes and Cure. I collected quite a library of old radical and socialist books and periodicals and pamphlets dating from the days of Hunt and Owen down to modern times.

I have never read Karl Marx. I have read many synopses of his teaching, and that has been quite enough for me. I have met a few men who claim to have read and studied the three huge volumes of Das Kapital, but the fact that they were still alive makes one inclined to cast some doubt about their claim. Neither Keir Hardie nor William Morris derived their socialism from Karl Marx.

(9) Philip Snowden, An Autobiography (1934)

Under capitalism it was greatly to the benefit of the individual to spend his wages on useful things instead of upon drink, though temperance alone would not touch the rot causes of low wages and poverty. The way I put the case in after years, when I often publicly discussed this question, was that drink is an aggravation of every social evil, and, in a great many cases, the prime cause of industrial misery and degradation. The economic waste of expenditure on drink lowers the standard of living and reduces a great many families to destitution, who, if their incomes were usefully spent, would enjoy a reasonable degree of comfort. Universal temperance would undoubtedly bring incalculable benefits and blessings, but so long as the social system is based upon exploitation the mass of the people will remain comparatively poor.

(10) The Weekly Sun (July, 1907)

Philip Snowden is small of stature and frail of frame, with a limp that compels him to lean heavily on a stick as he walks, he regards the world unblinkingly out of a pair of piercing eyes deep-sunken beneath an overhanging brow, across which wisps of lank hair are drawn. The skin is pallid, the cheeks hollow, giving an additional sharpness to the hawk-like nose and the tight-drawn inscrutable lips. and then the hands! Long, thin, and nervous, their fingers twist and writhe and contort themselves like the serpents on the head of Medusa, till shudderingly one draws back instinctively out of their reach.

(11) In his book An Autobiography, Philip Snowden criticised the WSPU.

So long as these women confined their activities to such ingenuous performances as tying themselves to street lamps and park railings, throwing leaflets from the Gallery of the House on the heads of members, or getting themselves arrested for causing obstruction, the public were more amused than angry, though the opponents of women suffrage never failed to point to these antics as proof of the unfitness of women to vote. When they began to destroy property and risk the lives of others than themselves the public began to turn against them. The National Union of Woman's Suffrage Societies, whose gallant educational and constitutional work for women's freedom had been carried on for more than fifty years, publicly dissociated themselves from these terrorist activities.

(8) Philip Snowden, An Autobiography (1934)

I have always been an advocate of what is called "Gradualism" in social progress. "Gradualism" does not mean that progress must necessarily be slow. The rate of advance must depend upon the intelligence of the democracy. But I do insist, and have done so from my earliest days of my Socialist teaching, that every step forward must carry with it the approval of public opinion, and that every change must be consolidated before the next step is taken.

(9) Philip Snowden, An Autobiography (1934)

During the nine days of the strike I remained silent. From one point of view I was not sorry that this experiment had been tried. The Trade Unions needed a lesson of the futility and foolishness of such a trial of strength. A general strike could in no circumstances be successful. A general strike is an attempt to hold up the community, and against such an attempt the community will mobilize all its resources. There is no country in the world which has proportionally such a large middle-class population as Great Britain. They with the help of governmental organisation, with a million motor-cars at their service, could defeat any strike on a large scale which threatened the vital services.

(14) Ramsay MacDonald appointed Clement Attlee as Postmaster General in 1929. He wrote about MacDonald's government in his autobiography, As It Happened (1954)

In the old days I had looked up to MacDonald as a great leader. He had a fine presence and great oratorical power. The unpopular line which he took during the First World War seemed to mark him as a man of character. Despite his mishandling of the Red Letter episode, I had not appreciated his defects until he took office a second time. I then realised his reluctance to take positive action and noted with dismay his increasing vanity and snobbery, while his habit of telling me, a junior Minister, the poor opinion he had of all his Cabinet colleagues made an unpleasant impression. I had not, however, expected that he would perpetrate the greatest betrayal in the political history of this country. I had realised that Snowden had become a docile disciple of orthodox finance, but I had not thought him capable of such virulent hatred of those who had served him loyally. The shock to the Party was very great, especially to the loyal workers of the rank-and-file who had made great sacrifices for these men.

Instead of deciding on a policy and standing or falling by it, MacDonald and Snowden persuaded the Cabinet to agree to the appointment of an Economy Committee, under the chairmanship of Sir George May of the Prudential Insurance Company, with a majority of opponents of Labour on it. The result might have been anticipated. The proposals were directed to cutting the social services and particularly unemployment benefit. Their remedy for an economic crisis, one of the chief features of which was excess of commodities over effective demand, was to cut down the purchasing power of the masses. The majority of the Government refused to accept the cuts and it was on this issue that the Government broke up. Instead of resigning, MacDonald accepted a commission from the King to form a so-called 'National' Government.

(15) Morgan Philips Price, My Three Revolutions (1969)

In February 1931, Philip Snowden made a speech in the House which created a sensation. He hinted at large economy measures, including cuts in the social services and unemployment benefit, in order to balance the coming Budget and maintain the gold standard. Meanwhile wholesale prices continued to fall on a world scale, businesses were losing money in some cases and making very little in others, so that revenue from taxes was declining. A big budget deficit was foreseen. In this debate I remember Lloyd George spoke and referred to the Chancellor sitting on ice surrounded by 'the penguins of the City'. Having received Snowden's speech with stony silence, we on the Labour benches roundly cheered Lloyd George.

The next day there was a meeting of the Parliamentary Labour Party. Snowden soundly rated us like naughty schoolboys for having done this. I remember many of us, including myself, replied that we would applaud anyone who talked sense, but we did not get that from some of our leaders.

(16) In his autobiography Philip Snowden described telling the Trade Union Congress about his plans in 1931 to cut wages and unemployment benefits (1934)

The spokesman of the Trade Unions was Mr. Bevin and Mr. Citrine, the Secretary of the Trade Union Committee. This deputation took up the attitude of opposition to practically all the economy proposals which had been explained to them. They opposed any interference with the existing terms and conditions of the Unemployment Insurance Scheme, including the limitation of statutory benefit to 26 weeks. We were told the Trade Unions would oppose the suggested economies on teachers' salaries and pay of the men in the Fighting Services, and any suggestions for reducing expenditure on works in relief of unemployment. The only proposal to which the General Council were not completely opposed was that the salaries of Ministers and Judges should be subjected to a cut!

(17) David Kirkwood, My Life of Revolt (1935)

On August 1, 1931, a National Government was formed. In November the country was thrown into the turmoil of a general election. What an election! I was terribly upset, more than tongue can tell, at the attack made upon the Labour Party by its former leaders.

Admitting that the Party had failed as a Government, it was Ramsay MacDonald, Philip Snowden, and J. H. Thomas who had been the three strongest leaders. But they blamed the rank and file. Some of us were worthy of blame. Our attitude had undoubtedly weakened the Government. But to attack the whole Party and the whole Movement was unjust.

The speeches of Philip Snowden made me think of a case in Glasgow where a man threw vitriol in the face of the girl he had jilted. It was inexcusable.