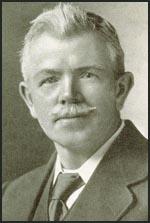

John Robert Clynes

John Robert Clynes, one of seven children of Patrick Clynes, an illiterate Irish farmworker, and his wife, Bridget Scanlan, was born in Oldham on 27th March 1869. His father had been evicted in 1851 and emigrated to Lancashire, where he gained employment as a gravedigger.

Clynes began work as a piecer at the local cotton mill when he was ten years old. He later recalled: "I remember no golden summers, no triumphs at games and sports, no tramps through dark woods or over shadow-racing hills. Only meals at which there never seemed to be enough food, dreary journeys through smoke-fouled streets, in mornings when I nodded with tiredness and in evenings when my legs trembled under me from exhaustion."

James Smith Middleton has pointed out: "Out of his early wages he bought a tattered dictionary for 6d. and Cobbett's Grammar for 8d. He received 3d. a week for reading regularly to three blind men, whose discussions of the political news aroused his interest. He paid 8d. for tuition on two nights a week from a former schoolmaster."At the age of sixteen, Clynes wrote a series of anonymous articles about life in a cotton mill. The articles illustrated the harsh way children were still being treated in textile factories. Clynes argued that the Spinners Union was not doing enough to protect child workers and in 1886 he helped form the Piercers' Union.

In 1892 Will Thorne recruited Clynes as organiser of the Lancashire Gasworkers' Union. Clynes joined the Fabian Society where he met George Bernard Shaw, Edward Carpenter and Sidney Webb. He also joined the Independent Labour Party and was one of the delegates at the conference in February, 1900 that established the Labour Representation Committee. A few months later Clynes was elected as one of the Trade Union representatives on the LRC executive.

Clynes was a talented writer and in the early 1900s became a regular contributor to socialist newspapers such as The Clarion. Clynes, the Secretary of Oldham's Trade Council, was asked to be the Labour Party candidate for North East Manchester in the 1906 General Election. Clynes won the seat soon established himself as one of the leaders of the party in Parliament. Like George Lansbury and Philip Snowden, Clynes was a strong supporter of votes for women.

A popular and well-respected member of the House of Commons, Clynes was elected as vice-chairman of the Labour Party in 1910. Ramsay MacDonald, the chairman of the party, was totally against Britain's involvement in the First World War. His views were shared by other senior figures such as James Keir Hardie, Philip Snowden, George Lansbury and Fred Jowett. Others in the party such as Clynes, Arthur Henderson, George Barnes, Will Thorne and Ben Tillett believed that the movement should give total support to the war effort.

On 5th August, 1914, the parliamentary party voted to support the government's request for war credits of £100,000,000. Ramsay MacDonald immediately resigned the chairmanship. He wrote in his diary: "I saw it was no use remaining as the Party was divided and nothing but futility could result. The Chairmanship was impossible. The men were not working, were not pulling together, there was enough jealously to spoil good feeling. The Party was no party in reality. It was sad, but glad to get out of harness." Arthur Henderson, once again, became the leader of the party.

In May 1915, Henderson became the first member of the Labour Party to hold a Cabinet post when Herbert Asquith invited him to join his coalition government. Bruce Glasier commented in his diary: "This is the first instance of a member of the Labour Party joining the government. Henderson is a clever, adroit, rather limited-minded man - domineering and a bit quarrelsome - vain and ambitious. He will prove a fairly capable official front-bench man, but will hardly command the support of organised Labour." Clynes initially opposed the entry of Labour into the Herbert Asquith coalition. However, he continued to support the war effort and in July 1917 the Prime Minister, David Lloyd George, rewarded Clynes by appointing him as Parliamentary Secretary of the Ministry of Food in his coalition government.

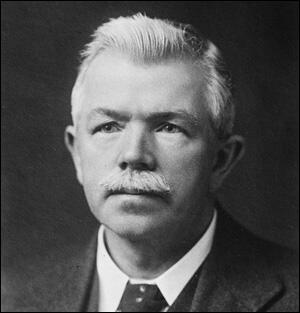

William Adamson replaced Arthur Henderson as chairman of the party in October 1917. In the 1918 General Election, a large number of the Labour leaders lost their seats. This included Henderson, Ramsay MacDonald, Philip Snowden, George Lansbury and Fred Jowett. Adamson held the post until February 1921 when he was replaced by Clynes. Snowden commented: "Clynes had considerable qualifications for Parliamentary leadership. He was an exceptionally able speaker, a keen and incisive debater, had wide experience of industrial questions, and a good knowledge of general political issues. In the Labour Party Conferences when the platform got into difficulties with the delegates, Mr. Clynes was usually put up to calm the storm."

Clynes was strongly opposed to working with the Communist Party of Great Britain: "In countries where no democratic weapon exists a class struggle for the enthronement of force by one class over other classes may be condoned, but in this country where the wage-earners possess 90 per cent of the voting power of the country agitation to use not the power which is possessed but some risky class dictatorship is a futile and dangerous doctrine."

In the 1922 General Election the Labour Party won 142 seats, making it the second largest political group in the House of Commons after the Conservative Party (347). David Marquand has pointed out that: "The new parliamentary Labour Party was a very different body from the old one. In 1918, 48 Labour M.P.s had been sponsored by trade unions, and only three by the ILP. Now about 100 members belonged to the ILP, while 32 had actually been sponsored by it, as against 85 who had been sponsored by trade unions.... In Parliament, it could present itself for the first time as the movement of opinion rather than of class."

At a meeting of the Parliamentary Labour Party on 21st November, 1922, Emanuel Shinwell proposed Ramsay MacDonald should become chairman. David Kirkwood, a fellow Labour MP, commented: "Nature had dealt unevenly with them. She had endowed MacDonald with a magnificent presence, a full resonant voice, and a splendid dignity. Clynes was small, unassuming, of uneven features, and voice without colour." After much discussion, Clynes received 56 votes to MacDonald's 61. Clynes, with characteristic generosity, declared that the whole party was determined to support the new leader.

In the 1923 General Election, the Labour Party won 191 seats. Although the Conservatives had 258, MacDonald agreed to head a minority government, and therefore became the first member of the party to become Prime Minister. MacDonald had the problem of forming a Cabinet with colleagues who had little, or no administrative experience. As MacDonald had to reply on the support of the Liberal Party, he was unable to get any socialist legislation passed by the House of Commons. Clynes was appointed lord privy seal and deputy leader of the House of Commons.

When MacDonald became Prime Minister again after the 1929 General Election, he appointed Joseph Clynes as his Home Secretary. Clynes was active in the area of prison reform and also ordered an inquiry into the cotton trade. However, he caused some controversy when he refused permission for Leon Trotsky to settle in England. As James Smith Middleton has pointed out: "In 1931 Clynes introduced an electoral reform bill providing for the alternative vote, and also abolishing university representation, a clause which was deleted by four votes in the committee stage in the House of Commons."

The election of the Labour Government coincided with an economic depression and MacDonald was faced with the problem of growing unemployment. MacDonald asked Sir George May, to form a committee to look into Britain's economic problem. When the May Committee produced its report in July, 1931, it suggested that the government should reduce its expenditure by £97,000,000, including a £67,000,000 cut in unemployment benefits. MacDonald, and his Chancellor of the Exchequer, Philip Snowden, accepted the report but when the matter was discussed by the Cabinet, the majority, including Clynes, George Lansbury and Arthur Henderson voted against the measures suggested by the May Committee.

Ramsay MacDonald was angry that his Cabinet had voted against him and decided to resign. When he saw George V that night, he was persuaded to head a new coalition government that would include Conservative and Liberal leaders as well as Labour ministers. Most of the Labour Cabinet totally rejected the idea and only three, Philip Snowden, Jimmy Thomas and John Sankey agreed to join the new government.

In October, MacDonald called an election. The 1931 General Election was a disaster for the Labour Party with only 46 members winning their seats. Clynes lost his seat at North East Manchester. He now devoted himself to the work of his union, the National Union of General and Municipal Workers, it covered nearly half a million members in a wide range of industries.

Clynes returned to the House of Commons at the 1935 General Election. Now sixty-years old he was considered an elder statesman of the labour movement. In 1945 he retired on reaching the parliamentary age limit set by his union and lived quietly on the pension which it gave him, in his Putney home. In 1947 he complained to The Times about his insufficient pension" and a fund was raised by his former parliamentary colleagues.

John Robert Clynes died at his home, 41 St John's Avenue, Putney Hill, on 23rd October, 1949.

Primary Sources

(1) J. R. Clynes, Memoirs (1937)

In 1851, when he was a quiet farm worker in Ireland, a Parliamentary Act which he did not understand was passed, like a divine decree, and Patrick Clynes, with hundreds of others, suffered the cruelties of eviction, and was left to find a new way of living. He could not find it in Ireland; but the cotton boom in Lancashire was attracting thousands of machine-minders, and he went to Oldham, where he worked in a mill.

My father, from his twenty-four shillings, paid a penny or two a week each for myself and my brother and five sisters, so that we should receive the education he had missed. My school master taught me nothing except a fear of birching and a hatred of formal education. My school days have no pleasant memories.

When I achieved the manly age of ten I obtained half-time employment at Dowry Mill as a "little piecer." My hours were from six in the morning each day to noon; then a brief time off for dinner; then on to school for the afternoons; and I was to receive half a crown a week in return.

The noise was what impressed me most. Clatter, rattle, bang, the swish of thrusting levers and the crowding of hundreds of men, women and children at their work. Long rows of huge spinning-frames, with thousands of whirling spindles, slid forward several feet, paused and then slid smoothly back again, continuing the process unceasingly hour after hour while cotton became yarn and yarn changed to weaving material.

Often the threads on the spindles broke as they were stretched and twisted and spun. These broken ends had to be instantly repaired; the piecer ran forward and joined them swiftly, with a deft touch that is an art of its own.

I remember no golden summers, no triumphs at games and sports, no tramps through dark woods or over shadow-racing hills. Only meals at which there never seemed to be enough food, dreary journeys through smoke-fouled streets, in mornings when I nodded with tiredness and in evenings when my legs trembled under me from exhaustion.

(2) J. R. Clynes, Memoirs (1937)

In advocating wider universal education I received much bitter opposition. Elderly spinners claimed bitterly that "learning" only made the youngsters discontented, and taught them to cry for the moon. "What was good enough for me ought to be good enough for my children" was the basis of their belief. The mill owners, too, threw their weight solidly against the unsettling influence of education. They wanted steady workers; it did not suit their ends that the workers should know too much.

(3) J. R. Clynes, Memoirs (1937)

I bought a copy of John Mitchell's Jail Journal in an Oldham junk-shop in 1888, and the author's patriotism, courage and loyalty to his country affected my feelings in a way I have not yet forgotten. But books of my own were rare luxuries. Most of my reading was done in the Oldham Equitable Co-operative Society's library. I sat at the table reading Shakespeare, Ruskin and Dickens, or whatever else I could get hold of. I remember my discovery of Julius Caesar, and how the realization came suddenly to me that it was a mighty political drama, not just an entertainment.

(4) James Haslam, the Secretary of the Piercers Union in Oldham described a meeting that too place in 1888.

The turn of Clynes came about nine o'clock. He was nothing to look at - a frail lad, pale and serious in ungainly clothes. For three-quarters of an hour the piecer-orator spoke with well-measured sentences of sincerity and grammatical precision. The audience, which had not been easy to control, laughed with him, and were sad with him.

Afterwards the chairman of the committee said to me: "Where did you get that lad from? This country will know summat about him - if he lives!"

(5) J. R. Clynes, Memoirs (1937)

Looking back I am awed at the task we undertook. That Labour should have progressed so much in less than a hundred years is very short of a miracle. It has been said that faith can make mountains move from their appointed places. Faith was the only thing that upheld us in the early days. Collarless, moneyless, almost wordless, we earnestly believed that it was wrong for the ill-educated to be exploited for the benefit of the aristocrats. We were prepared to die for our faith, knowing that others would come after us to whom our failing hands could throw the torch.

(6) In 1892 Clynes was employed by the Gasworkers Union. This resulted in him taking his first journey away from Oldham.

Millions of men and women died in their own towns and villages without ever having travelled five miles from the spot where they were born. How vividly I remember my first long journey away from Oldham. I had to attend a conference of the Gasworkers Union at Plymouth. To get there entailed a railway journey down the length of England.

Men of my own class were driving the engine and acting as porters. I remember a sensation of power as I glimpsed a future in which all these men would be teamed up together with mill-hands, seamen, gas-workers - in fact, Labour everywhere - for the benefit of our own people.

The least change of accent in speech, as we stopped at various towns, fascinated me, and I noted varieties of face, dress and manner. That was a wonderful journey for me, who had never before been out of the Lancashire murk. To look through the carriage windows and see grass and bushes that were really green instead of olive, trees that reached confidently up to the sun instead of our stunted things, houses that were mellow red and white and yellow, with warm red roofs, instead of the Lancashire soot and slates, and stretches of landscape in which the eye could not find a single factory chimney belching - this was sheer magic!

I began to experience an inexhaustible wonder at the gracious beauties of the world outside factory-land, and this sensation has never wholly left me. That first long railway journey was as wonderful to me as if I had been riding upon the magic carpet in the Arabian Nights.

And more and more strongly as I gazed, I felt a sense of indignation that the world should be so generous and so lovely, and yet that men, women and children should be cooped up in a black and exhausted industrial areas like Oldham, merely so that richer men could own thousands of acres of sunlit countryside of whose experience many of the mill-workers hardly ever dreamed.

(7) J. R. Clynes, Memoirs (1937)

George Bernard Shaw agreed to take the chair for me at a Fabian Society meeting. The meeting was a great success. Shaw has always been a brilliant speaker as well as a provocative writer. During the early years of the Fabian Society he spoke constantly at public meetings, drawing crowded audiences. He always gave of his best, whether there were two thousand listeners or only twenty. That is the hallmark of the true artist.

(8) J. R. Clynes, Memoirs (1937)

In the 1906 General Election Labour victories were recorded from towns as far apart as Bolton, Newcastle, Bradford, Leicester, Leeds, Halifax, Norwich and Dundee. When the last results were published we found that we had won a stupendous victory. In the previous Parliament the Labour Party had been represented by 4 members; now, out of 50 candidates, we has 29 successful returns.

(9) J. R. Clynes, Memoirs (1937)

The Old Age Pensions Act was brought in by Mr. Lloyd George, and provided pensions for some half a million men and women over seventy years of age. But it was a well-recognised fact that the Liberals would never have supported these Bills in their final form, save for the pressure of Labour behind them, which made them fearful of losing their position as the professedly reformist Party in Parliament.

(10) J. R. Clynes, Memoirs (1937)

Hardie died of a broken heart. He had always been a pacifist, and had fiercely opposed the South African War, being nearly killed in Glasgow during a riot caused by one of his speeches there against it. Between the end of the South African War and 1914 he burned himself out working to try and prepare a tremendous international general strike, to be declared when the European War, which he could see was coming, broke out. This strike he hoped would paralyze hostilities and bring immediate peace.

When August, 1914, showed him that his hopes were vain, that the workers' leaders he had painfully taught were marching to war and singing their respective patriotic songs, and when British Labour refused to inaugurate a great strike on behalf of peace, Hardie became a broken man. For the next twelve months the old dominant figure we had known was seen no more in the corridors of the House of Commons; he shrank into a travesty of his former self, never spoke in debates and said little to anyone. The great leader of Labour was dying on his feet. We all loved and respected him; it was a great grief to us that our attitude to war was driving the sword into his heart; but between our conscience and our friend there was only one choice.

(11) J. R. Clynes, Memoirs (1937)

Much of the delay in our production of war supplies was due to sheer incompetence, but more of it was attributable to the will of the profiteers, who constantly deliberately kept the Government short in order that famine prices should be offered to stimulate their output. Thousands of the shells supplied in 1914 and 1915 were more dangerous to their users than to the Germans, and hundreds of our own artillerymen and many guns were blown up in trying to fire them. Meanwhile, men at the heads of great British armament firms were speedily becoming millionaires by betraying the common soldiers who were dying for them at the front.

(12) David Kirkwood wrote about the election for the leadership of the Labour Party in 1922 in his autobiography My Life of Revolt (1935)

Ramsay MacDonald was the son of a Lossiemouth farm-servant. He started as a pupil teacher, had come to London and earned a scanty living with the Cyclists' Touring Club, later as Secretary of the Scottish Home Rule Association, and thereafter as a journalist. He had been Secretary of the Labour Party from 1900 to 1912, and Chairman from 1912 to 1914.

John Clynes was a poor boy in Oldham who started work in a cotton factory and entered Parliament in 1906. For his services during the War he had been made a Privy Councillor and had been honoured by the Universities of Durham and Oxford, both of which conferred upon him the degree of D.C.L.

Nature had dealt unevenly with them. She had endowed MacDonald with a magnificent presence, a full resonant voice, and a splendid dignity. Clynes was small, unassuming, of uneven features, and voice without colour.

(13) Philip Snowden, An Autobiography (1934)

Joseph Clynes had considerable qualifications for Parliamentary leadership. He was an exceptionally able speaker, a keen and incisive debater, had wide experience of industrial questions, and a good knowledge of general political issues. In the Labour Party Conferences when "the platform" got into difficulties with the delegates, Mr. Clynes was usually put up to calm the storm.

Student Activities

Walter Tull: Britain's First Black Officer (Answer Commentary)

Football and the First World War (Answer Commentary)

Football on the Western Front (Answer Commentary)

Käthe Kollwitz: German Artist in the First World War (Answer Commentary)

American Artists and the First World War (Answer Commentary)