The Communist Party of Great Britain

On 31st July, 1920, a group of revolutionary socialists attended a meeting at the Cannon Street Hotel in London. The men and women were members of various political groups including the British Socialist Party (BSP), the Socialist Labour Party (SLP), Prohibition and Reform Party (PRP) and the Workers' Socialist Federation (WSF). It was agreed to form the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB). Arthur McManus was elected as the party's first chairman and Tom Bell and Harry Pollitt became the party's first full-time workers. (1)

It later emerged that Lenin had provided at least £55,000 (over £1 million in today's money) to help fund the CPGB. Early members included Willie Paul, Rajani Palme Dutt, Helen Crawfurd, A. J. Cook, Albert Inkpin, J. T. Murphy, Arthur Horner, Rose Cohen, Tom Mann, Ralph Bates, Winifred Bates, Rose Kerrigan, Peter Kerrigan, Bert Overton, Hugh Slater, Ralph Fox, Dave Springhill, William Mellor, Robin Page Arnot, John Ross Campbell, Bob Stewart, Shapurji Saklatvala, Ellen Wilkinson, George Aitken, Dora Montefiore, Sylvia Pankhurst and Robin Page Arnot.

The first resolution passed at the Communist Unity Convention covered the main aims of the new party: "The Communists in Conference assembled declare for the Soviet (or Workers' Councils) system as a means whereby the working class shall achieve power and take control of the forces of production. Declare the dictatorship of the proletariat as a necessary means of combating counter-revolution during the transition period between capitalism and communism, and stand for the adoption of these measures as a step towards the establishment of a system of complete communism wherein the means of production shall be communally owned and controlled. This Conference therefore establishes itself the Communist Party on the foregoing basis and declares its adhesion to the Communist International." (2)

Affiliation to the Labour Party

On of the first major debates on policy concerned the possible affiliation to the Labour Party. At the Communist Unity Convention, the majority of the speakers argued strongly against the strategy suggested by Lenin that the CPGB should develop a close relationship with the Labour Party. Tom Bell argued passionately that in order to "rally together all the elements in the country in favour of Communism was to make it clear that we have no associations with and did not stand for the same policy as the Labour Party." (3)

Willie Paul admitted that Lenin was a great revolutionary leader but he was not infallible. On general principles and international developments we should follow Lenin, but on questions of tactics for Britain we know best: "There is not one in this audience to whom I yield in admiration for Lenin... but Lenin is no pope or god... on local circumstances, where we are on the spot, we are the people to decide." (4)

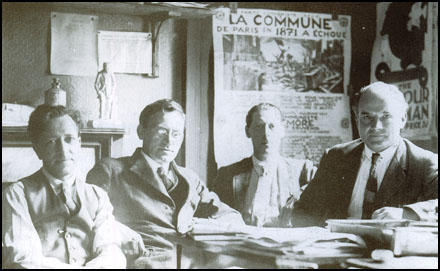

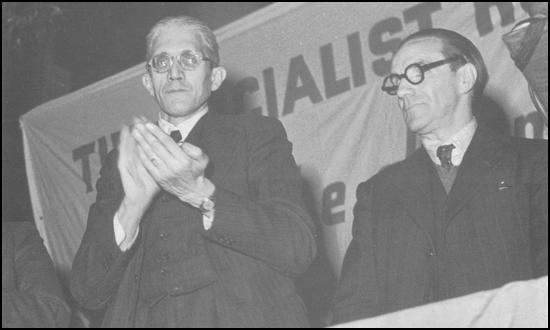

William Gallacher, Wal Hannington; (Middle Row): Harry Pollitt, Ernie Cant,

Tom Wintringham, Albert Inkpin; (Front Row): John R. Campbell,

Arthur McManus, William Rust, Robin Page Arnot, Tom Bell

J. F. Hodgson, a former member of the British Socialist Party, argued strongly that the Communist Party should be trying to recruit members from the trade unions. "May I remind you that you meet the same people in the Labour Party, and that you meet them on a much larger field than you do in the trade unions... It is truly said that the mission of our Party is to be the vanguard of the revolutionary working class. You cannot be the vanguard unless you are going to march with the working class." (5)

Another delegate, Robin Page Arnot, suggested that it was wrong to compare the Labour Party to other working-class parties in the rest of Europe. He emphasised the special character of the Labour Party, especially the loose federation, with socialist parties of different outlooks as members, and mass trade union affiliation, and showed how this demanded a different approach from that of say the German Social Democratic Party. (6)

Bob Stewart advocated the need to work closely with the Labour Party and other working-class organisations to obtain change: "Our job is to be where the laws are made." He was supported by Ellen Wilkinson, who delivered a revolutionary speech for parliamentary action, saying: "A revolution must mean discipline and obedience to working-class principles." Wilkinson eventually became a minister in a Labour government but as Stewart pointed out: "She certainly used parliament, but I am afraid not for the revolutionary principles she espoused that day." (7)

When the final vote was taken it showed a small majority of 100 to 85 for affiliation to the Labour Party. As James Klugmann, the author of the History of the Communist Party of Great Britain: Formation and Early Years (1969), had pointed out, "by previous agreement the minority was committed to the majority decision, but this did not, in fact, mean by any means that they had as yet been intellectually convinced." (8)

Every effort was made to cover up the split in the party. Willie Paul, who had led the campaign against affiliation, wrote in The Communist that if Lenin, Karl Radek and Nickolai Bukharin argued in favour of this measure, than maybe he was wrong: "We of the Communist Unity Group feel our defeat on the question of Labour Party affiliation very keenly. But we intend to loyally abide by the decision of the rank and file convention... The comrades who voted in favour of the Labour Party were undoubtedly influenced by the arguments put forth on this question by Lenin, Radek, and many other Russian Communists. We believe that these heroic comrades, in urging Labour Party affiliation, have erred on a question of tactics. But we frankly admit that the very fact that Lenin, Radek, Bukharin, and the others advise such a policy is a very good reason why a number of delegates thought we were perhaps in the wrong." (9)

William Gallacher was another revolutionary who was opposed to affiliation with the Labour Party. However, he changed his mind after meeting Lenin in Moscow. He later recalled: "It was on... the conception of the Party that the genius of Lenin had expressed itself... Before I left Moscow, I had an interview with Lenin during which he asked me three questions. Do you admit you were wrong on the question of Parliament and affiliation to the Labour Party? Will you join the CP when you return? Will you do your best to persuade your Scottish comrades to join it? To each of these questions I answered yes." (10)

Tom Bell also admitted he changed his mind on this issue when Lenin explained to him that it would be a useful weapon against Ramsay Macdonald, Arthur Henderson, Philip Snowden, and other right-wing leaders of the Labour Party. "Lenin's principal line was that by affiliating to the Labour Party, and on the assumption that it gave us freedom of criticism and we retained our independence as a party, we should be able to push the Labour Party forward in this period, thereby exposing the Hendersons, Snowdens and MacDonalds, and assisting to free the working class from traitors." (11)

On 10th August, 1920, the Communist Party applied to be affiliated to the Labour Party. However, when it was discussed at the Labour Party conference that year it received little support from the leaders of the party. Arthur Henderson made a speech where he quoted a Communist Party leaflet that had been distributed during a recent by-election where Ramsay Macdonald, was the candidate. Henderson quoted the leaflet as saying: "The Communist Party feels it cannot allow the decision to run Ramsay MacDonald to pass without comment... While the coalition candidate stands for capitalism in all its manifestations... the Labour Party candidate also stands for capitalism in all its manifestations." (12)

John R. Clynes, the leader of the Labour Party at the time, was also strongly opposed to working with the Communist Party: "In countries where no democratic weapon exists a class struggle for the enthronement of force by one class over other classes may be condoned, but in this country where the wage-earners possess 90 per cent of the voting power of the country agitation to use not the power which is possessed but some risky class dictatorship is a futile and dangerous doctrine." The conference voted 4,115,000 to 224,000 against allowing the Communist Party to affiliate. (13)

It is claimed that by 1921 the CPGB had 2,500 members. Albert Inkpin was elected as National Secretary of the CPGB. Later that year he was arrested and charged with printing and circulating Communist Party literature. He was found guilty and sentenced to six months in prison. Bob Stewart, the National Organiser for Scotland, was also arrested and charged with making seditious speeches. He was also found guilty and was sentenced to three months' hard labour in Cardiff Gaol. (14)

Albert Inkpin, Rajani Palme Dutt and Harry Pollitt were charged with the task of implementing the organisational theses of the Comintern. As Jim Higgins has pointed out: "In the streamlined “bolshevised” party that came out of the re-organisation, all three signatories reaped the reward of their work. Inkpin was elected chairman of the Central Control Commission Dutt and Pollitt were elected to the party executive. Thus started the long and close association between Dutt and Pollitt. Palme Dutt, the cool intellectual with a facility for theoretical exposition, with friends in the Kremlin and Pollitt the talented mass agitator and organiser." (15)

Shapurji Saklatvala became the party's candidate in North Battersea. His chances of victory increased significantly when his election agent, John Archer, persuaded the local Labour Party not to oppose Saklatvala. With the support of the Battersea Trades Council, Saklatvala won the seat in the 1922 General Election. However, in the election the following year, Saklatvala lost the seat to the Liberal Party candidate by 186 votes. (16)

The Labour Government and the Soviet Union

In the 1923 General Election, the Labour Party won 191 seats. David Marquand has pointed out that: "The new parliamentary Labour Party was a very different body from the old one. In 1918, 48 Labour M.P.s had been sponsored by trade unions, and only three by the ILP. Now about 100 members belonged to the ILP, while 32 had actually been sponsored by it, as against 85 who had been sponsored by trade unions.... In Parliament, it could present itself for the first time as the movement of opinion rather than of class." (17)

Although the Conservative Party had 258 seats, Herbert Asquith announced that the Liberal Party would not keep the Tories in office. If a Labour Government were ever to be tried in Britain, he declared, "it could hardly be tried under safer conditions". The Daily Mail warned about the dangers of a Labour government and the Daily Herald commented on the "Rothermere press as a frantic attempt to induce Mr Asquith to combine with the Tories to prevent a Labour Government assuming office". (18) John R. Clynes, the former leader of the Labour Party, argued: "Our enemies are not afraid we shall fail in relation to them. They are afraid that we shall succeed." (19)

On 22nd January, 1924 Stanley Baldwin resigned. At midday, the 57 year-old, Ramsay MacDonald went to Buckingham Palace to be appointed prime minister. He later recalled how George V complained about the singing of the Red Flag and the La Marseilles, at the Labour Party meeting in the Albert Hall a few days before. MacDonald apologized but claimed that there would have been a riot if he had tried to stop it. (20)

The Labour government received constant criticism from the newspapers that were controlled by a group of wealthy individuals who strongly supported the Conservative Party. In return they had been given titles and places in the House of Lords. This included Alfred Harmsworth, Lord Northcliffe (The Daily Mail and The Times), Harold Harmsworth, Lord Rothermere (The Daily Mirror), Harry Levy-Lawson, Lord Burnham (The Daily Telegraph) and William Maxwell Aitken, Lord Beaverbrook (The Daily Express). (21)

The most hostile response to the new Labour government was Lord Northcliffe, the owner of several Conservative Party supporting newspapers. The Daily Mail claimed during the election campaign that it was under the control of the Bolshevik government in the Soviet Union: "The British Labour Party, as it impudently calls itself, is not British at all. It has no right whatever to its name. By its humble acceptance of the domination of the Sozialistische Arbeiter Internationale's authority at Hamburg in May it has become a mere wing of the Bolshevist and Communist organisation on the Continent. It cannot act or think for itself." (22)

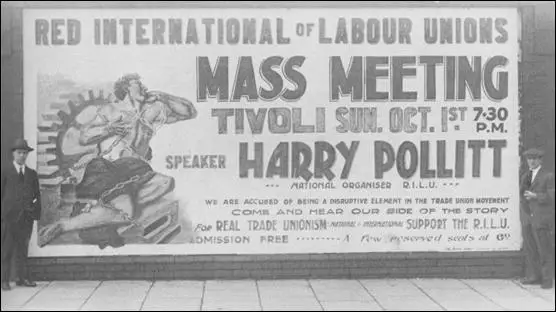

On 25th July 1925, the Worker's Weekly, a newspaper controlled by the Communist Party of Great Britain, published an "Open Letter to the Fighting Forces" that had been written anonymously by Harry Pollitt. The article called on soldiers to "let it be known that, neither in the class war nor in a military war, will you turn your guns on your fellow workers, but instead will line up with your fellow workers in an attack upon the exploiters and capitalists and will use your arms on the side of your own class." (23)

After consultations with the Director of Public Prosecutions and the Attorney General, Sir Patrick Hastings, it was decided to arrest and charge, John Ross Campbell, the editor of the newspaper, with incitement to mutiny. The following day, Hastings had to answer questions in the House of Commons on the case. However, after investigating Campbell in more detail he discovered that he was only acting editor at the time the article was published, he began to have doubts about the success of a prosecution. (24)

The matter was further complicated when James Maxton informed Hastings about Campbell's war record. In 1914, Campbell was posted to the Clydeside section of the Royal Naval division and served throughout the war. Wounded at Gallipoli, he was permanently disabled at the battle of the Somme, where he was awarded the Military Medal for conspicuous bravery. Hastings was warned about the possible reaction to the idea of a war hero being prosecuted for an article published in a small circulation newspaper. (25)

At a meeting on the morning of the 6th August, Hastings told MacDonald that he thought that "the whole matter could be dropped". MacDonald replied that prosecutions, once entered into, should not be dropped under political pressure". At a Cabinet meeting that evening Hastings revealed that he had a letter from Campbell confirming his temporary editorship. Hastings also added that the case should be withdrawn on the grounds that the article merely commented on the use of troops in industrial disputes. MacDonald agreed with this assessment and agreed the prosecution should be dropped. (26)

On 13th August, 1924, the case was withdrawn. This created a great deal of controversy and MacDonald was accused of being soft on communism. MacDonald, who had a long record of being a strong anti-communist, told King George V: "Nothing would have pleased me better than to have appeared in the witness box, when I might have said some things that might have added a month or two to the sentence." (27)

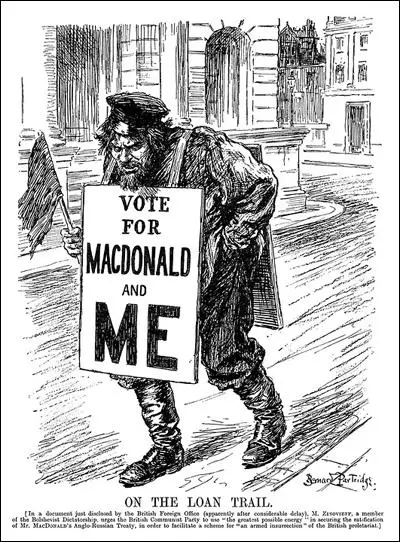

On 10th October 1924, MI5 received a copy of a letter, dated 15th September, sent by Grigory Zinoviev, chairman of the Comintern in the Soviet Union, to Arthur McManus, the British representative on the committee. In the letter British communists were asked to take all possible action to ensure the ratification of the Anglo-Soviet Treaties. It then went on to advocate preparation for military insurrection in working-class areas of Britain and for subverting the allegiance in the army and navy. (28)

Hugh Sinclair, head of MI6, provided "five very good reasons" why he believed the letter was genuine. However, one of these reasons, that the letter came "direct from an agent in Moscow for a long time in our service, and of proved reliability" was incorrect. (29) Vernon Kell, the head of MI5 and Sir Basil Thomson the head of Special Branch, were also convinced that the Zinoviev Letter was genuine. Desmond Morton, who worked for MI6, told Sir Eyre Crowe, at the Foreign Office, that an agent, Jim Finney, who worked for George Makgill, the head of the Industrial Intelligence Bureau (IIB), had penetrated Comintern and the Communist Party of Great Britain. Morton told Crowe that Finney "had reported that a recent meeting of the Party Central Committee had considered a letter from Moscow whose instructions corresponded to those in the Zinoviev letter". However, Christopher Andrew, who examined all the files concerning the matter, claims that Finney's report of the meeting does not include this information. (30)

Kell showed the letter to Ramsay MacDonald, the Labour Prime Minister. It was agreed that the letter should be kept secret until it was discovered to be genuine. (31) Thomas Marlowe, who worked for the press baron, Alfred Harmsworth, Lord Rothermere, had a good relationship with Reginald Hall, the Conservative Party MP, for Liverpool West Derby. During the First World War he was director of Naval Intelligence Division of the Royal Navy (NID) and he leaked the letter to Marlowe, in an effort to bring an end to the Labour government. (32)

The newspaper now contacted the Foreign Office and asked if it was a forgery. Without reference to MacDonald, a senior official told Marlowe it was genuine. The newspaper also received a copy of the letter of protest sent by the British government to the Russian ambassador, denouncing it as a "flagrant breach of undertakings given by the Soviet Government in the course of the negotiations for the Anglo-Soviet Treaties". It was decided not to use this information until closer to the election. (33)

David Lloyd George signed a trade agreement with Russia in 1921, but never recognised the Soviet government. On taking office the Labour government entered into talks with Russian officials and eventually recognised the Soviet Union as the de jure government of Russia, in return for the promise that Britain would get payment of money that Tsar Nicholas II had borrowed when he had been in power. (34)

Edmund D. Morel, the Labour Party MP for Dundee, was involved in these negotiations. He told his friend, Bob Stewart, that it was very difficult to reach a negotiated agreement with the Soviet representatives because of the demands being made by the Conservative Party: "The Tories vehemently against. They demanded compensation for British property in the Soviet Union which had been nationalised by the Soviet government, and also trading rights for British firms on Soviet territory. The first was realisable, but naturally the Soviet government would not entertain the latter." (35)

A conference was held in London to discuss these matters. Most newspapers reacted with hostility to these negotiations and warned of the danger of dealing with what they considered to be an "evil regime". in August 1924 a wide-ranging series of treaties was agreed between Britain and Russia. "The most-favoured-nation status was given to the Soviet Union in exchange for concessions to British holders of Czarist bonds, and Britain agreed to recommend a loan to the Soviet government." (36)

Stanley Baldwin, the leader of the Conservative Party, and H. H. Asquith, the leader of the Liberal Party, decided to being the Labour government down over the issue of its relationship with the Soviet Union. On 30th September, the Liberals condemned the recently agreed trade deal. They claimed, unjustly, that Britain had given the Russians what they wanted without resolving the claims of British bondholders who had suffered in the revolution. "MacDonald reacted peevishly to this, accusing them of being unscrupulous and dishonest." (37)

The following day, Conservatives put down a censure motion on the decision to drop the case against John Ross Campbell. The debate took place on 8th October. MacDonald lost the vote by 364 votes to 198. "Labour was brought down, on the Campbell case, by the combined ranks of Conservatives and Liberals... The Labour government had lasted 259 days. On six occasions the Conservatives had saved MacDonald from defeat in the 1923 parliament, but it was the Liberals who pulled the political rung from under him." (38)

1924 General Election

The Daily Mail published the Zinoviev Letter on 25th October 1924, just four days before the 1924 General Election. Under the headline "Civil War Plot by Socialists Masters" it argued: "Moscow issues orders to the British Communists... the British Communists in turn give orders to the Socialist Government, which it tamely and humbly obeys... Now we can see why Mr MacDonald has done obeisance throughout the campaign to the Red Flag with its associations of murder and crime. He is a stalking horse for the Reds as Kerensky was... Everything is to be made ready for a great outbreak of the abominable class war which is civil war of the most savage kind." (39)

Dora Russell, whose husband, Bertrand Russell, was standing for the Labour Party in Chelsea, commented: "The Daily Mail carried the story of the Zinoviev letter. The whole thing was neatly timed to catch the Sunday papers and with polling day following hard on the weekend there was no chance of an effective rebuttal, unless some word came from MacDonald himself, and he was down in his constituency in Wales. Without hesitation I went on the platform and denounced the whole thing as a forgery, deliberately planted on, or by, the Foreign Office to discredit the Prime Minister." (40)

Ramsay MacDonald suggested he was a victim of a political conspiracy: "I am also informed that the Conservative Headquarters had been spreading abroad for some days that... a mine was going to be sprung under our feet, and that the name of Zinoviev was to be associated with mine. Another Guy Fawkes - a new Gunpowder Plot... The letter might have originated anywhere. The staff of the Foreign Office up to the end of the week thought it was authentic... I have not seen the evidence yet. All I say is this, that it is a most suspicious circumstance that a certain newspaper and the headquarters of the Conservative Association seem to have had copies of it at the same time as the Foreign Office, and if that is true how can I avoid the suspicion - I will not say the conclusion - that the whole thing is a political plot?" (41)

Bob Stewart, a senior figure in the Communist Party, claimed that the letter included several mistakes that made it clear it was a forgery. This included saying that Grigory Zinoviev was not the President of the Presidium of the Communist International. It also described the organisation as the "Third Communist International" whereas it was always called "Third International". Stewart argued that these "were such infantile mistakes that even a cursory examination would have shown the document to be a blatant forgery." (42)

The rest of the Tory owned newspapers ran the story of what became known as the Zinoviev Letter over the next few days and it was no surprise when the election was a disaster for the Labour Party. The Conservatives won 412 seats and formed the next government. Lord Beaverbrook, the owner of the Daily Express and Evening Standard, told Lord Rothermere, the owner of The Daily Mail and The Times, that the "Red Letter" campaign had won the election for the Conservatives. Rothermere replied that it was probably worth a hundred seats. (43)

Imprisonment of Communist Leaders

After the poor general election result, it has been argued that Ramsay MacDonald and other right-wing members of the Labour Party, decided that they wanted scapegoats, and who better than the communists? At the Labour Party conference following the election it was decided to exclude, not only the Communist Party as an organization, but also individual members. At this time the Communist Party had 10,730 members. (44)

On 4th August 1925, 12 party activists, John Ross Campbell, Jack Murphy, Wal Hannington, Ernie Cant, Tom Wintringham, Harry Pollitt, Hubert Inkpin, Arthur McManus, William Rust, Robin Page Arnot, William Gallacher and Tom Bell were arrested for being members of the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB) and were charged with violation of the Mutiny Act of 1797. The hearing at Bow Street was before Sir Chartres Biron, described by Gallacher as "an ideal subject for Dickens, majestic, pompous, fully convinced of his high responsibility as custodian of the law and safety of the realm." (45)

While the men were on remand the CPGB had a secret meeting. Bob Stewart later recalled what happened: "After discussion it was decided to elect an acting executive and officials, and that no publicity would be given to this, because naturally the new leaders could easily follow the twelve into prison, so an entire silence was maintained. To my astonishment I was elected acting general secretary . This was a new role for me, and also in new conditions. Before, I was always one of those in jail looking out at the fight. Now I was outside and with a heavy responsibility." (46)

Claims that it was a political trial was reinforced when Rigby Swift was appointed as judge. He was a member of the Conservative Party and was elected to represent St Helens in December 1910 but was easily beaten by James Sexton in the general election that followed the end of the First World War. In June 1920 he was appointed by his friend, Frederick Smith, Lord Birkenhead, the Lord Chancellor, as judge of the High Court of Justice. The decision was welcomed by the right-wing press. The Daily Mail wrote that "Mr. Rigby Swift has long been marked out for judgeship" and The Times added that "no appointment could be met with greater approval". (47)

Tom Bell, the author of British Communist Party (1937), the CPGB responded as if it was a political trial. "The Political Bureau discussed the procedure of the trial and decided that Campbell, Gallacher and Pollitt should defend themselves; their speeches were prepared, and approved by the Political Bureau." (48) Their three speeches "made an exposition of Communist politics, theory and practice which thousands of workers read with appreciation." (49)

Pollitt's 15,000 word speech took three hours. He argued that the political motivation behind the prosecution was the proposed General Strike as the "government sought to remove from the political arena the most effective exponents of united action by the working class to aid the miners". He then warned the jury against the newspaper build-up of prejudice against the Communists. Pollitt went on to say that "the destruction of Monarchies, of Tsarism, not as the result of Communist propaganda, but as the result of conditions created by capitalism." (50)

To challenge the legality of the proceedings Sir Henry Slesser was engaged to defend the others. During the trial Judge Rigby Swift declared that it was "no crime to be a Communist or hold communist opinions, but it was a crime to belong to this Communist Party." It was argued that the Soviet Union had given the CPGB £14,000. During the trial Gallacher showed this money was the income from the sale of newspapers and fees paid by the 5,000 members. (51)

After a trial that lasted eight days, the twelve defendants were found guilty on all charges. Judge Swift told the men: "The jury have found you twelve men guilty of the serious offence of conspiracy to publish seditious libels and to incite people to induce soldiers and sailors to break their oaths of allegiance. It is obvious from the evidence that you are members of an illegal party carrying on illegal work in this country. Five of you, Inkpin, Gallacher, Pollitt, Hannington and Rust will go to prison for twelve months."

Judge Swift then went on to say: "You remaining seven have heard what I have had to say about the society to which you belong. You have heard me say it must be stopped.... Those of you who will promise me that you will have nothing more to do with this association or the doctrine it preaches, I will bind over to be of good behaviour in the future. Those of you who do not promise will go to prison." (52)

Jack Murphy, Ernie Cant, Tom Wintringham, Arthur McManus, Robin Page Arnot, and Tom Bell all refused and were each sentenced to six months. (53) As one commentator pointed out: "And there it was, men supposedly found guilty of the worst charges in the crime calendar were to be let off all they had to do was to cease being Communists. Very touching, but it gave away the aim of the whole trial, which was to try and destroy the Communist Party and so behead the working-class movement." (54)

Campbell later wrote: "The Government was wise enough not to rest its case on the activity of the accused in organising resistance to wage cuts, but on their dissemination of 'seditious' communist literature, (particularly the resolutions of the Communist International), their speeches, and occasional articles". The idea of a "an ex-Tory M.P. sitting in judgement upon the Communists and offering them liberty at the price of apostasy" aroused considerable criticism. Walter Citrine, Secretary of the TUC said: "In my view a most unsuitable judge was selected" and the Liberal Party MP, William Wedgwood Benn argued that "the sentences are perfectly iniquitous". (55) Judge Swift's biographer rejected these criticisms claiming that "the plain fact is that when a barrister who has been a party politician ascends to the Bench he sheds his politics completely". (56)

The Daily Worker

In 1929, Albert Inkpin and Andrew Rothstein were removed from the leadership of the CPGB. "Rothstein, in particular, was disliked for his elitist, arrogant manner and his lack of contact with the rank and file. He was banished to Moscow, leaving behind a wife and two children without means of support. The eponymous Albert Inkpin was a clear scapegoat. Thin, pale and hardworking, the chief administrator of the Party since its inception, he had served two prison terms on its behalf. Now he was accused, maliciously and completely falsely, of running a pub on the side and helping himself to some of the 'Moscow Gold' that he had husbanded for many years on the Party's behalf." (57)

This period saw the CPGB at its lowest ebb. Despite the Great Depression, membership was down to 3,500. In the 1929 General Election the Labour Party obtained 8,370,417 votes and won 287 seats, enabling Ramsay MacDonald to form a minority government. Harry Pollitt, the general secretary, realised the CPGB had serious problems and he admitted that "the transmission belts were turning no wheels" and that "the bridge to the masses has become only the same faithful few going over in every case". (58)

Pollitt recruited Tom Wintringham to help establish a new CPGB newspaper. Wintringham found premises at 41 Tabernacle Street, London EC2. On 1st January 1930, launched The Daily Worker. Wintringham later commented: "So we got it out on time with antiquated machinery, makeshift organisation, candles lighting the grim warehouse that was our office, the newspaper trains closed to us." (59)

William Rust became the first editor of the newspaper. Rust was described by a colleague at this time as "round and pink and cold as ice." Another friend said that he rarely saw him smile. His biographer, Kevin Morgan, pointed out that he was chosen because it was claimed that "even among his fellow communists for his quite exceptional devotion to Moscow." (60)

Rust made it clear from the beginning that the newspaper was going to be an organ of agitation. "There was little news in the Daily Worker in the early days, unless you wanted to read very politically slanted articles about unemployment, strikes and the Soviet Union, or absurd sectarian propaganda". (61) Lenin was quoted in the first edition as saying: "without a political organ, a movement deserving to be called a political movement is impossible in modern Europe." (62)

On 25th January 1930, Rajani Palme Dutt, wrote an article in the newspaper condemning the inclusion of sports news: "Capitalist sport is subordinate to bourgeois politics, run under bourgeois patronage and breathing the spirit of patriotism and class unity; and often of militarism, fascism and strike breaking. Sport is a hotbed of propaganda and recruiting for the enemy. Spectator sports (horse racing and football) are profit run professional spectacles thick with corruption. They are dope; to distract the workers from the bad conditions of their lives, to stop thinking, to make passive wage slaves. You cannot reconcile revolutionary politics with capitalist sport!" (63)

It was decided to stop covering sport. This was unpopular and Wintringham later recalled: "I had to pay printers with I.O.U.s, stave off landlord and business, keep the paper going in spite of a mountain of debts for paper and machinery." After only a few weeks the circulation had dropped from 45,000 to 39,000 and the newspaper was losing £500 a week. Pollitt wrote to John Ross Campbell in Moscow and told him about "a financial problem that I do not know how to face". Eventually it was arranged for the Soviet Union to fund the venture. However, "Pollitt knew that the money he got to run the Daily Worker depended on Moscow's approval of its contents." (64)

The 1931 General Election was held on 27th October, 1931. Ramsay MacDonald led an anti-Labour alliance made up of Conservatives and National Liberals. It was a disaster for the Labour Party with only 46 members winning their seats. The Government parties polled 14,500,000 votes to Labour's 6,600,000. It was also a disaster for the Communist Party of Great Britain winning only 74,824 votes. Shapurji Saklatvala, the former MP for North Battersea, failed to regain his seat. Membership of the party now fell to 6,000. (65)

However, unemployment continued to grow under MacDonald's National Government and the Communist Party was able to recruit new members. Fred Copeman joined after being impressed with the work done in Deptford: "Kath and Sandy Duncan were both leading members of the Communist Party... Both were school teachers, and both gave unstinted service to the Party and to the working people. Their enthusiasm and integrity were infectious which quickly had its effect on me and I joined the Communist Party." (66)

Stalinism and the Communist Party

On 1st December, 1934, Sergey Kirov was assassinated by a young party member, Leonid Nikolayev. It was argued that the conspiracy was led by Leon Trotsky. This resulted in the arrest of Lev Kamenev, Gregory Zinoviev, Nikolay Bukharin, Ivan Smirnov, Mikhail Tomsky and Alexei Rykov and other party members who had been critical of Joseph Stalin. (67) In the Daily Worker, Pollitt argued that the proposed trial represented "a new triumph in the history of progress". (68)

The first ever show show trial took place in August, 1936, of sixteen party members. Yuri Piatakov accepted the post of chief witness "with all my heart." Max Shachtman pointed out: "The official indictment charges a widespread assassination conspiracy, carried on these five years or more, directed against the head of the Communist party and the government, organized with the direct connivance of the Hitler regime, and aimed at the establishment of a Fascist dictatorship in Russia. And who are included in these stupefying charges, either as direct participants or, what would be no less reprehensible, as persons with knowledge of the conspiracy who failed to disclose it?" (69)

The men made confessions of their guilt. Lev Kamenev said: "I Kamenev, together with Zinoviev and Trotsky, organised and guided this conspiracy. My motives? I had become convinced that the party's - Stalin's policy - was successful and victorious. We, the opposition, had banked on a split in the party; but this hope proved groundless. We could no longer count on any serious domestic difficulties to allow us to overthrow. Stalin's leadership we were actuated by boundless hatred and by lust of power." (70)

Gregory Zinoviev also confessed: "I would like to repeat that I am fully and utterly guilty. I am guilty of having been the organizer, second only to Trotsky, of that block whose chosen task was the killing of Stalin. I was the principal organizer of Kirov's assassination. The party saw where we were going, and warned us; Stalin warned as scores of times; but we did not heed these warnings. We entered into an alliance with Trotsky." (71)

On 24th August, 1936, Vasily Ulrikh announced that all sixteen defendants were sentenced to death by shooting. The following day Soviet newspapers carried the announcement that all sixteen defendants had been put to death. This included the NKVD agents who had provided false confessions. Joseph Stalin could not afford for any witnesses to the conspiracy to remain alive. Edvard Radzinsky, the author of Stalin (1996), has pointed out that Stalin did not even keep his promise to Kamenev's sons and later both men were shot. (72)

Most journalists covering the trial were convinced that the confessions were statements of truth. The Observer reported: "It is futile to think the trial was staged and the charges trumped up. The government's case against the defendants (Zinoviev and Kamenev) is genuine." (73) The The New Statesman commented: "Very likely there was a plot. We complain because, in the absence of independent witnesses, there is no way of knowing. It is their (Zinoviev and Kamenev) confession and decision to demand the death sentence for themselves that constitutes the mystery. If they had a hope of acquittal, why confess? If they were guilty of trying to murder Stalin and knew they would be shot in any case, why cringe and crawl instead of defiantly justifying their plot on revolutionary grounds? We would be glad to hear the explanation." (74)

In January, 1937, Yuri Piatakov, Karl Radek, Grigori Sokolnikov, and fifteen other leading members of the Communist Party were put on trial. They were accused of working with Leon Trotsky in an attempt to overthrow the Soviet government with the objective of restoring capitalism. Piatakov had been the main witness against Lev Kamenev and Gregory Zinoviev in 1936: "After they saw that Piatakov was ready to collaborate in any way required, they gave him a more complicated role. In the 1937 trials he joined the defendants, those whom he had meant to blacken. He was arrested, but was at first recalcitrant. Ordzhonikidze in person urged him to accept the role assigned to him in exchange for his life. No one was so well qualified as Piatakov to destroy Trotsky, his former god and now the Party's worst enemy, in the eyes of the country and the whole world. He finally agreed I to do it as a matter of 'the highest expediency,' and began rehearsals with the interrogators." (75)

Yuri Piatakov and twelve of the accused were found guilty and sentenced to death. Maria Svanidze, who was later herself to be purged by Stalin wrote in her diary: "They arrested Radek and others whom I knew, people I used to talk to, and always trusted.... But what transpired surpassed all my expectations of human baseness. It was all there, terrorism, intervention, the Gestapo, theft, sabotage, subversion.... All out of careerism, greed, and the love of pleasure, the desire to have mistresses, to travel abroad, together with some sort of nebulous prospect of seizing power by a palace revolution. Where was their elementary feeling of patriotism, of love for their motherland? These moral freaks deserved their fate.... My soul is ablaze with anger and hatred. Their execution will not satisfy me. I should like to torture them, break them on the wheel, burn them alive for all the vile things they have done." (76)

These convictions were criticised by Leon Trotsky, who was living in exile in Mexico City. In his article The Trial of the Seventeen, he asked: "How could these old Bolsheviks who went through the jails and exiles of Czarism, who were the heroes of the civil war, the leaders of industry, the builders of the party, diplomats, turn out at the moment of 'the complete victory of socialism' to be saboteurs, allies of fascism, organizer of espionage, agents of capitalist restoration? Who can believe such accusations? How can anyone be made to believe them. And why is Stalin compelled to tie up the fate of his personal rule with these monstrous, impossible, nightmarish juridical trials?" (77)

William Gallacher went to Moscow to express his concerns about the Great Purge. He went to see Georgi Dimitrov who told him: "Comrade Gallacher, it is best that you do not pursue these matters." Gallacher took this advice and remained a staunch Stalinist. He told his family that "not speaking the language and being shepherded about everywhere, it was hard to know what was really going on." The Comintern laid down the correct line for the CPGB to take. Trotsky's supporters were "mean degenerates" and "abominable traitors". (78)

Left Book Club and the Show Trials

In 1936, Victor Gollancz, formed the Left Book Club. It had over 45,000 and 730 local discussion groups, and it estimated that these were attended by an average total of 12,000 people every fortnight. The Left Book Club published several books written by members of the Communist Party of Great Britain. This included the defence of the Soviet Show Trials. This included the "suppression of some of his (Gollancz) most fundamental instincts and cherished beliefs" and included his "ready acceptance of Stalinist propaganda concerning the Moscow trials, despite the disquiet widely evident among socialists". (79)

Gollancz worked very closely with Harry Pollitt, the general secretary of the CPGB. At the Royal Albert Hall in February 1937, Pollitt made clear that while the Club was not a communist organisation, "its publications and discussions revealed for the first time in Britain a hunger for Marxism." It brought forward new writers who "expressed in their creative writing an understanding of what Marxism means and are influencing sections to whom a short time ago the name of Marx was a bogey." (80)

Gollancz was vice-president of the National Committee for the Abolition of the Death Penalty but he agreed to Pollitt's suggestion that he published a defence of the prosecution and execution of former members of the Soviet government. Dudley Collard was approached to write a book on the legality of the Soviet Show Trials. The book was entitled Soviet Justice and the Trial of Radek and Others. (81)

Published in May, 1937, the book praised Andrey Vyshinsky, the state prosecutor in the show trials. "Vyshinsky handled the case admirably. He was single-handed, without a junior or a solicitor to assist him and he obviously had a complete mastery of all the details of the activities of each of the seventeen defendants, activities which spread in many cases over five or six years. It was a considerable feat to conduct the prosecution, as he did, without once hesitating or faltering for seven days. He never once lost his temper or bullied a defendant, although his examination was skilful and searching. He invariably behaved with restraint and courtesy". (82)

Dudley Collard blamed the conflict in the Soviet government on Leon Trotsky and his belief in permanent revolution. "Trotsky and his supporters.... had no confidence in the ability of the Soviet people to build socialism in one country, surrounded as it was by hostile capitalist states. They took the view that to attempt to do so was to invite an armed attack and to suffer inevitable defeat." In the summer of 1931, on the orders of Trotsky, a group of senior figures in the party, including Lev Kamenev, Gregory Zinoviev, Nikolay Bukharin, Ivan Smirnov, Mikhail Tomsky, Alexei Rykov, Yuri Piatakov, and Karl Radek, took the view that it was "necessary to overthrow the Soviet Government". (83)

Collard claimed that Trotsky and his group decided they "would actively help the Germans and Japanese by collecting information and co-operating with their secret service, and by carrying out sabotage at important military factories and on strategic railways and that "when the war broke out they would redouble their sabotage". At the end of the war "the Germans and Japanese would place them in power" and in return "they would cede the Manchuria provinces to Japan.... The Germans could also have economic concessions for gold mines, oil, manganese, timber, apatites, and the Japanese the oil of Sakhalin Island." (84)

The CPGB put out a "War on Two Fronts" policy statement. It called for a real war against fascism and a political war against the government. It also demanded nationalisation of the arms industry and greater democracy in the armed forces. Tom Wintringham, who had expressed severe doubts about the Show Trials was expelled by the CPGB because he was living with Kitty Bowler, a non-party member who had been friendly with supporters of Leon Trotsky. "The Control Commission of the Communist Party had recommended the exclusion of Tom Wintringham for refusual to accept a decision of the Party to break off personal relations with elements considered undesirable by the Party. (85)

John Ross Campbell was the foreign correspondent of the Daily Worker in the Soviet Union and became a loyal supporter of Joseph Stalin in his attempts to purge the followers of Leon Trotsky. As Campbell was the CPGB representative in the Soviet Union, it is unlikely that he was unaware of what was really going on. (86) Along with Rajani Palme Dutt and Denis Nowell Pritt, Campbell were "enthusiastic apologists for the Moscow frame-up trials". (87)

Campbell wrote on 5th March 1938: "Every weak, corrupt or ambitious enemy of socialism within the Soviet Union has been hired to do dirty, evil work. In the forefront of all the wrecking, sabotage and assassination is Fascist agent Trotsky. But the defences of the Soviet Union are strong. The nest of wreckers and spies has been exposed before the world and brought before the judgement of the Soviet Court. We know that Soviet justice will be fearlessly administered to those who have been guilty of unspeakable crimes against Soviet people. We express full confidence in our Brother Party." (88)

In 1939 the Left Book Club published Campbell's Soviet Policy and its Critics, in defence of the Great Purge in the Soviet Union. He agreed with Dudley Collard that the main issue between Trotsky and Stalin was over the issue of "socialism in one country". He quoted Stalin as saying: "Our Soviet society has already, in the main, succeeded in achieving Socialism... It has created a socialist system; i.e., it has brought about what Marxists in other words call the first, or lower phase of Communism. Hence, in the main, we have already achieved the first phase of Communism, Socialism." (89)

Campbell explained that in his book, The Revolution Betrayed (1937) Trotsky pointed out that what had been achieved in the Soviet Union was merely a "preparatory regime transitional from capitalism to socialism". He went on to say that this preparatory regime is engendering growing inequalities between the members of society and that it is being controlled by a growing bureaucracy. Before this transitional society can develop towards Socialism, Trotsky asserts, it is imperative that there should be "a second supplementary revolution - against bureaucratic absolutism" and this "bureaucracy can be removed only by a revolutionary force. And, as always, there wall be fewer victims the more bold and decisive is the attack". (90)

Campbell argued that the opponents of the Show Trials had failed to understand the political development of Trotsky: "Most of the critics of the Moscow Trials disqualify themselves straight away by ignoring the historical development of Trotskyism. They learnedly discuss the 'mystery' of why the Trotskyists turned against the Soviet Government when the key to the mystery is partially disclosed in the earlier public writings of Trotsky himself. They assert the improbability of Trotsky organising the assassination of Stalin, at the very moment when Trotsky in his published work is describing how all power is being concentrated in Stalin's hands and is demanding the removal of Stalin by armed revolution. But if the armed revolution is slow in coming, would not the assassination of the man who has concentrated so much power in his hands accelerate the process?" (91)

It was later argued that Campbell had good reason to be uncritical of the Soviet government. He married Sarah Marie Carlin in 1920. He acted as father to five children from a previous marriage. Sarah encouraged her oldest son, William, to go to the Soviet Union and help build socialism. According to Francis Beckett, the author of Stalin's British Victims (2004), "with his stepson as a sort of hostage in the Soviet Union" he was not in a position to tell the truth of the way that loyal Bolsheviks were being persecuted. (92)

Rajani Palme Dutt used his journal, The Labour Monthly, to defend the Great Purge. "Together with D.N. Pritt he was an enthusiastic apologist for the Moscow frame-up trials. Russian communists he had known, some as friends, disappeared in the horror of the great purge, not a words, not a whisper escaped Dutt’s lips or his pen to indicate anything but peace and socialist construction were going on in Russia under the avuncular beneficence of Joe Stalin." (93) As Duncan Hallas pointed out: "He repeated every vile slander against Trotsky and his followers and against the old Bolsheviks murdered by Stalin through the 1930s, praising the obscene parodies of trials that condemned them as Soviet justice". (94)

The Percy Glading Case

Maxwell Knight was the head of B5b, a unit at MI5 that conducted the monitoring of political subversion. One of Knight's spies, Olga Grey joined the Friends of the Soviet Union. She soon gained the confidence of Percy Glading, the CPGB national organizer. According to Francis Beckett, the author of The Enemy Within (1995): "Olga Gray worked for the CP for six years, from 1931 to 1937, first as a volunteer and then full time at King Street. She was surprised to find herself growing to like these Bolsheviks of whom she had heard such hair-raising things. When she began to help Percy Glading with a scheme to convey plans of a British gun to the Soviet Union, she found herself liking the man. Although Olga wanted to give up her job with MI5 Knight managed to persuade her to stay on until Glading was in the net." (95)

Olga Grey accumulated proof that Glading had been recruiting sources inside the Woolwich Arsenal, and this was passed onto MI5. Glading, George Whomack and Charles Munday were arrested on 14th May, 1938. Glading was defended in court by Dudley Collard and Denis Nowell Pritt. (96) Evidence at their trial at the old Bailey including a mass of incriminating documents and photographic material found at the homes of both Glading and Williams. All three men were found guilty and Glading was given six years' imprisonment, Williams four and Whomack three. (97)

The Second World War

The leadership of the Communist Party of Great Britain was involved in the creation of the International Brigades during the Spanish Civil War. All the commanders of the British Battalion were party members. This included Wilfred Macartney, Tom Wintringham, George Aitken, Fred Copeman, Harry Fry, Bill Alexander and Sam Wild. The party also kept political control of the volunteers by appointing party members as political commissars. This included Wally Tapsell, Harry Dobson and Dave Springhill. (98)

The rise of fascism in Germany and Italy increased support for the Communist Party and after the signing of the Munich Agreement, membership reached 15,570. Members included Mary Valentine Ackland, Felicia Browne, Christopher Caudwell, James Friell, Claude Cockburn, John Cornford, Patience Darton, Len Crome, Ralph Fox, Nan Green, Charlotte Haldane, John Haldane, Christopher Hill, Rodney Hilton, Eric Hobsbawn, Lou Kenton, David Marshall, Jessica Mitford, A. L. Morton, Esmond Romilly, George Rudé, Raphael Samuel, Alfred Sherman, Thora Silverthorne and E. P. Thompson.

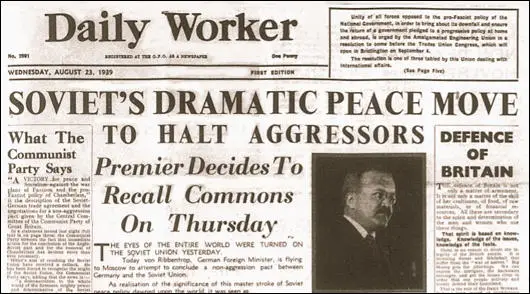

On 23rd August, 1939, Joseph Stalin signed the Soviet-Nazi Pact with Adolf Hitler. However, long-time loyalist, John Ross Campbell, felt he could no longer support this policy. "We started by saying we had an interest in the defeat of the Nazis, we must now recognise that our prime interest in the defeat of France and Great Britain... We have to eat everything we have said." Other leaders of the CPGB agreed with Campbell a statement was issued that "declared its support of all measures necessary to secure the victory of democracy over fascism". (99)

Harry Pollitt, the General Secretary of the CPGB, published a 32-page pamphlet, How to Win the War (1939): "The Communist Party supports the war, believing it to be a just war. To stand aside from this conflict, to contribute only revolutionary-sounding phrases while the fascist beasts ride roughshod over Europe, would be a betrayal of everything our forebears have fought to achieve in the course of long years of struggle against capitalism.... The prosecution of this war necessitates a struggle on two fronts. First to secure the military victory over fascism, and second, to achieve this, the political victory over the enemies of democracy in Britain." (100)

On 24th September, Dave Springhall, a CPGB member who had been working in Moscow, returned with the information that the Communist International characterised the war as an "out and out imperialist war to which the working class in no country could give any support". He added that "Germany aimed at European and world domination. Britain at preserving her imperialist interests and European domination against her chief rival, Germany." (101)

At a meeting of the Central Committee on 2nd October 1939, Rajani Palme Dutt demanded "acceptance of the (new Soviet line) by the members of the Central Committee on the basis of conviction". He added: "Every responsible position in the Party must be occupied by a determined fighter for the line." Bob Stewart disagreed and mocked "these sledgehammer demands for whole-hearted convictions and solid and hardened, tempered Bolshevism and all this bloody kind of stuff."

William Gallacher agreed with Stewart: "I have never... at this Central Committee listened to a more unscrupulous and opportunist speech than has been made by Comrade Dutt... and I have never had in all my experience in the Party such evidence of mean, despicable disloyalty to comrades." Harry Pollitt joined in the attack: "Please remember, Comrade Dutt, you won't intimidate me by that language. I was in the movement practically before you were born, and will be in the revolutionary movement a long time after some of you are forgotten."

Harry Pollitt then made a passionate speech about his unwillingness to change his views on the invasion of Poland: "I believe in the long run it will do this Party very great harm... I don't envy the comrades who can so lightly in the space of a week... go from one political conviction to another... I am ashamed of the lack of feeling, the lack of response that this struggle of the Polish people has aroused in our leadership." (102)

However, when the vote was taken, only John Ross Campbell, Harry Pollitt, and William Gallacher voted against. Pollitt was forced to resign as General Secretary and he was replaced by Rajani Palme Dutt and William Rust took over Campbell's job as editor of the Daily Worker. Pollitt, then agreed to disguise this conflict and issued a statement saying it was "nonsense and wishful thinking the attempts in the press to create the impression of a crisis in the Party". (103)

Over the next few weeks the newspaper demanded that Neville Chamberlain respond to Hitler's peace overtures. Palme Dutt also published a new pamphlet, Why This War? explaining the new policy of the CPGB. Campbell and Pollitt were both removed from the Politburo. (104) Campbell also "subsequently rationalized the Comintern's position and publicly confessed to error in having opposed it." (105) Douglas Hyde claims that Palme Dutt was clearly the "most powerful man in the Party". (106)

Fred Copeman was one of those who resigned from the Communist Party over this issue: "It has yearly become harder to make excuses to my conscience each time an action of the Soviet Government or the Communist Party has cut across my interpretation of personal freedom. The decision of the Russian Government to withhold arms to the Spanish Republic, in order that the Spanish Communist Party could gain a political point, needed some understanding. The trials of old Bolsheviks were even harder to swallow. The Soviet attack on Finland I found hard to accept, but was unable to prove completely wrong. Their alliance with the Nazis in 1939, aligned with the complete reversal of policy by our own Communist Party, forced me to begin to look elsewhere for an ideology and philosophy so fundamentally true that it would be possible for me to find real happiness in giving my all in the struggle for its acceptance by mankind." (107)

William Rust, John Ross Campbell and Douglas Hyde (1939)

On 22nd June 1941 Germany invaded the Soviet Union. That night Winston Churchill said: "We shall give whatever help we can to Russia." The CPGB immediately announced full support for the war and brought back Harry Pollitt as general secretary. As Jim Higgins has pointed out Palme Dutt's attitude towards the war was "immediately transformed into an anti-fascist crusade." (108)

In the early stages of the Second World War, the Home Secretary, Herbert Morrison, banned the Daily Worker. Following the German army's invasion of the Soviet Union in Operation Barbarossa, in June 1941, a campaign supported by Professor John Haldane and Hewlett Johnson, the Dean of Canterbury, began to allow the newspaper to be published. On 26th May 1942, after a heated debate, the Labour Party carried a resolution declaring the Government must lift the ban on the newspaper. The ban was lifted in August 1942. (109)

As Francis Beckett has pointed out: "Suddenly the Communist Party was popular and respectable, because Stalin's Russia was popular and respectable, and because at a time of war, Communists were able to wave the Union Jack with the best of them. Party leaders appeared on platforms with the great and the good. Membership soared: from 15,570 in 1938 to 56,000 in 1942." (110)

In 1943 Dave Springhill was arrested and charged with obtaining secret information from an Air Ministry employee and an army officer and passing it to the Soviet Union. He was sentenced to seven years penal servitude. As Christopher Andrew points out in his book, The Defence of the Realm (2009): "The CPGB leadership reacted with shocked surprise to Springhall's conviction, expelling him from the Party and publicly distancing itself from any involvement in espionage... In order to emphasize its British identity, at the Sixteenth Party Congress in July 1943 the Party decided to call itself the British Communist Party." (111)

The Cold War

William Gallacher was elected to represent East Fife in the 1945 General Election. Another member of the Communist Party, Phil Piratin, was elected to represent Mile End. In the House of Commons Gallacher and Piratin associated with a group of left-wing members that included John Platts-Mills, Konni Zilliacus, Lester Hutchinson, Ian Mikardo, Barbara Castle, Sydney Silverman, Geoffrey Bing, Emrys Hughes, D. N. Pritt, Leslie Solley and William Warbey. Piratin later recalled: "Gallacher was the straightest man in the world, we were like father and son." He was asked how the relationship worked: "It's quite simple: there are two of us and Gallacher is the elder, and therefore I automatically moved and he seconded that he should be the leader. He then appointed me as Chief Whip. Comrade Gallacher decides the policy and I make sure he carries it out." (112)

Officially, William Rust, the editor of the Daily Worker, remained in charge of the newspaper, however, Douglas Hyde, the news editor, later recalled: "We would sit in a room, just half a dozen of us, and talk about the political issues of the day." However, it was Rajani Palme Dutt who decided on the newspaper's policy. "When we had all had our say, Dutt would drape his arm over the arm of his chair - he had the longest arms I have ever seen - bang his pipe out on the sole of his shoe, and sum up. Often the summing up was entirely different from the conclusions we were all reaching, but no one ever argued." (113)

Rust attempted to turn the Daily Worker into a popular mass paper. According to Francis Beckett: "He was a fine editor: a cynical boss who thumped the table in his furious rages, he nonetheless inspired journalists' best work. A tall and by now heavily built man, Rust was one of the Party's most able people, and one of the least likeable." Sales of the newspaper reached 120,000 in 1948. (114)

Alison Macleod worked for the newspaper after the war. In her book, The Death of Uncle Joe (1997), she claimed that in private John Ross Campbell, the assistant editor, was highly critical of the actions of Joseph Stalin. He agreed with Tito in his dispute in June 1948 but in his articles he "refused to say that the Soviet Government was right, stopped short of making any public protest". Campbell argued that if you "were serious about wanting Socialism or you weren't. If you were serious, you couldn't attack the one country which had achieved it." (115)

William Rust, aged 46, died of a massive heart-attack on 3rd February 1949. John Ross Campbell once again became the editor of the Daily Worker. (116) According to one source he was an excellent journalist: "Johnny Campbell, who took over as editor after Rust's death in 1949, was in the great Scottish Communist tradition of worker intellectuals, a man". (117)

Campbell was liked and respected by his staff. One of his young sub-editors wrote: "Since then I have met several editors who put on matey airs. They imagine (as they lunch at the Savoy Grill) that the reporters lunching at the Wimpy Bar adore them. Campbell's matiness was real. He was interested in people. He would sit in the canteen we all used, and talk to compositors, tape boys or the latest recruit to the staff. Nobody could be better suited to keep the loyalty of a temperamental team, and hold it together amid external attacks." (118)

| The Performance of the Communist Party of Great Britain in British General Elections: 1922-1951 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

Year | Total Votes | % | MPs |

33,637 | 0.2 | 1 | |

39,448 | 0.2 | 0 | |

55,346 | 0.3 | 1 | |

50,634 | 0.2 | 0 | |

74,824 | 0.3 | 0 | |

27,177 | 0.1 | 1 | |

102,780 | 0.4 | 2 | |

91,765 | 0.3 | 0 | |

21,640 | 0.1 | 0 | |

Sam Russell became diplomatic correspondent of the Daily Worker. In 1952 he covered show-trial of Czechoslovakian Communist Party general secretary Rudolf Slansky and 13 other party leaders. At the time he considered the evidence as genuine but according to Roger Bagley it was an experience which left a deep scar." In 1955 Russell was sent to Moscow. During this period he became friendly with Guy Burgess and Donald Maclean. According to Colin Chambers, "Russell found his attempts to report the experience of everyday life an irritant both to the Soviet authorities and his editor in London. The Soviet Communist party even asked for Russell to be withdrawn, but the British Communist party refused." (119)

Communist Party Historians' Group

In 1946 several historians who were members of the Communist Party of Great Britain, that included Christopher Hill, E. P. Thompson, Raphael Samuel, Eric Hobsbawm, A. L. Morton, John Saville, George Rudé, Rodney Hilton, Dorothy Thompson, Dona Torr, Edmund Dell, Victor Kiernan and Maurice Dobb formed the Communist Party Historians' Group. (120) Francis Beckett pointed out that these "were historians of a new type - socialists to whom history was not so much the doings of kings, queens and prime ministers, as those of the people." (121)

The group had been inspired by A. L. Morton's People's History of England (1938). Christopher Hill, the group's chairman, argued that the book provided a "broad framework" for the group's subsequent work in posing "an infinity of questions to think about"; for Eric Hobsbawm, it would become a model in how to write searching but accessible history, whereas for Raphael Samuel, who first encountered the book as a schoolboy, it was an antidote to "reactionary" history from above. According to Ben Harker: "Morton was an inspiration for a rising generation of Marxist historians who would come to dominate their respective fields." (122)

Eric Hobsbawm has argued that: "The main pillars of the Group thus consisted initially of people who had graduated sufficiently early in the 1930s to have done some research, to have begun to publish and, in very exceptional cases, to have begun to teach. Among these Christopher Hill already occupied a special position as the author of a major interpretation of the English Revolution and a link with Soviet economic historians." (123)

John Saville later recalled: "The Historian's Group had a considerable long-term influence upon most of its members. It was an interesting moment in time, this coming together of such a lively assembly of young intellectuals, and their influence upon the analysis of certain periods and subjects of British history was to be far-reaching. For me, it was a privilege I have always recognised and appreciated." (124)

In 1952 members of the group founded the journal, Past and Present. Over the next few years the journal pioneered the study of working-class history and is "now widely regarded as one of the most important historical journals published in Britain today." (125)

As Christos Efstathiou has explained: "Most of the members of the Group had common aspirations as well as common past experiences. The majority of them grew up in the inter-war period and were Oxbridge undergraduates who felt that the path to socialism was the solution to militarism and fascism. It was this common cause that united them as a team of young revolutionaries, who saw themselves as the heir of old radical." (126)

Khrushchev's de-Stalinzation Policy

During the 20th Party Congress in February, 1956, Nikita Khrushchev launched an attack on the rule of Joseph Stalin. He condemned the Great Purge and accused Stalin of abusing his power. He argued: "Stalin acted not through persuasion, explanation and patient co-operation with people, but by imposing his concepts and demanding absolute submission to his opinion. Whoever opposed this concept or tried to prove his viewpoint, and the correctness of his position, was doomed to removal from the leading collective and to subsequent moral and physical annihilation. This was especially true during the period following the 17th Party Congress, when many prominent Party leaders and rank-and-file Party workers, honest and dedicated to the cause of communism, fell victim to Stalin's despotism." (127)

Harry Pollitt found it difficult to accept these criticisms of Stalin and said of a portrait of his hero that hung in his living room: "He's staying there as long as I'm alive". Francis Beckett pointed out: "Pollitt believed, as did many in the 1930s, that only the Soviet Union stood between the world and universal Fascist dictatorship. On balance, he reckoned Stalin was doing more good than harm; he liked and admired the Soviet leader; and persuaded himself that Stalin's crimes were largely mistakes made by subordinates. Seldom can a man have thrown away his personal integrity for such good motives." (128)

However, according to his biographer, John Mahon, Pollitt found Khrushchev's speech upsetting: "Pollitt was far too human a person to regard the Stalin disclosures with personal detachment, they were as painful for him as far for thousands of other responsible Communists, and he was fully aware that they were giving rise to new and complex problems for the Party. Immediately following the Congress, he showed visible signs of physical exhaustion." On 25th April, 1956, he experienced a loss of ability to read following a haemorrhage behind the eyes. Unable to do his job properly he resigned as general secretary of the Communist Party. (129)

James Friell (Gabriel), the political cartoonist on the Daily Worker, argued that the newspaper should play its part in condemning Stalinism. Gabriel drew a cartoon that showed two worried people reading the Khrushchev speech. Behind them loomed two symbolic figures labelled "humanity" and "justice". He added the caption: "Whatever road we take we must never leave them behind." As a fellow worker at the newspaper, Alison Macleod, pointed out in her book, The Death of Uncle Joe (1997): "This brought some furious letters from our readers. One of them called the cartoon the most disgusting example of the non-Marxist, anti-working class outbursts." However, Macleod went on to point out that a large number of party members shared Friell's sentiments. (130)

Khrushchev's de-Stalinzation policy encouraged people living in Eastern Europe to believe that he was willing to give them more independence from the Soviet Union. In Hungary the prime minister Imre Nagy removed state control of the mass media and encouraged public discussion on political and economic reform. Nagy also released anti-communists from prison and talked about holding free elections and withdrawing Hungary from the Warsaw Pact. Khrushchev became increasingly concerned about these developments and on 4th November 1956 he sent the Red Army into Hungary. (131)

Peter Fryer, the Daily Worker journalist in Budapest was highly critical of the actions of the Soviet Union, and was furious when he discovered his reports were censored. Fryer responded by having the material published in the New Statesman. As a result he was suspended from the party for "publishing in the capitalist press attacks on the Communist Party." Campbell now sent the loyal Sam Russell to report on the uprising. (132)

Malcolm MacEwen, one of the journalists drafted a petition on the reporting of the uprising and persuaded nineteen out of the thirty-one staff of the newspaper to sign it. MacEwen made reference to Edith Bone, a journalist from the Daily Worker who had been in a Budapest prison since 1949. "The imprisonment of Edith Bone in solitary confinement without trial for seven years, without any public inquiry or protest from our Party even after the exposure of the Rajk trial had shown that such injustices were taking place, not only exposes the character of the regime but involves us in its crimes. It is now clear that what took place was a national uprising against an infamous police dictatorship." (133)

Campbell turned on MacEwen. He later commented: "I don't think I've ever loved anybody more than I loved Johnnie Campbell". He was shocked when his best friend was suddenly transformed into his worst enemy, denouncing him so venomously that he knew what Laszlo Rajk and Rudolf Slánský must have felt. He felt he could not carrying on like this and he resigned from both the newspaper and the Communist Party. (134)

Fryer told Campbell he must resign from the newspaper. Campbell pleaded with him to stay. He told Fryer that he had been in Moscow during the purges of the 1930s; he had known what was going on. But what could he do? How could he say anything in public, when the war was coming and the Soviet Union was going to be attacked. Alison Macleod, who watched this debate going on later commented: "This might have been some excuse for silence. However, Campbell was not silent in the 1930s. He wrote a book: Soviet Policy and its Critics, which was published by Gollancz in 1939. In this he defended every action of Stalin and argued the purge trials were genuine." (135)

James Friell condemned John Ross Campbell for supporting the invasion. He told Campbell: "How could the Daily Worker keep talking about a counter-revolution when they have to call in Soviet troops? Can you defend the right of a government to exist with the help of Soviet troops? Gomulka said that a government which has lost the confidence of the people has no right to govern." When Campbell refused to publish a cartoon by Friell on the Hungarian Uprising he left the newspaper. "I couldn't conceive carrying on cartooning about the evils of capitalism and imperialism," he wrote, "and ignoring the acknowledged evils of Russian communism." (136)

Campbell pleaded with the other journalists who were considering leaving the newspaper: "I am one of those who detest any possibility of a return to Stalinism. I have a very simple request to make to any comrades planning to leave the paper. Think it over for 24 hours! Do not do it in a way which will inflict the maximum injury on our paper... If a leading member of the staff leaves the paper at this moment it is not an ordinary act but a deadly blow." (137)

Over 7,000 members of the Communist Party of Great Britain resigned over what happened in Hungary. One of them later recalled: "The crisis within the British Communist Party, which is now officially admitted to exist, is merely part of the crisis within the entire world Communist movement. The central issue is the elimination of what has come to be known as Stalinism. Stalin is dead, but the men he trained in methods of odious political immorality still control the destinies of States and Communist Parties. The Soviet aggression in Hungary marked the obstinate re-emergence of Stalinism in Soviet policy, and undid much of the good work towards easing international tension that had been done in the preceding three years. By supporting this aggression the leaders of the British Party proved themselves unrepentant Stalinists, hostile in the main to the process of democratisation in Eastern Europe. They must be fought as such." (138)

Arnold Wesker had joined the Communist Party a few years earlier, had little difficulty resigning: "The Communist Parties of the world and especially of Britain suddenly found that Stalin and his policy which they once praised was now in disgrace; that the men they once criticised as reactionaries and traitors were not so; that the men whose deaths they once condoned were in fact innocent. There has been a fantastic spate of letters in the Daily Worker from Party members who are virtually in tears that they had ever been so lacking in courage.... It is as though they had all gone to a mass confessional and with terrible secrets in their heart now out in the open they feel new people."

His mother, Leah Wesker, who had joined in the early days of the movement found the speech made by Nikita Khrushchev very distressing. "Leah, my mother... does not know what has happened, what to say or feel or think. She is at once defensive and doubtful. She does not know who is right. To her the people who once criticised the party and were called traitors are still traitors despite that the new attitude suggests this is not the case. And this is Leah. To her there was either black or white, communists or fascists. There were no shades... If she admits that the party has been wrong, that Stalin committed grave offences, then she must admit that she has been wrong. All the people she so mistrusted and hated she must now have second thoughts about, and this she cannot do - because having bound her politics so closely to her personality she must then confess a weakness in her personality. You can admit the error of an idea but not the conduct of a whole life." (139)

In 1959 George Matthews became the new editor of the Daily Worker. According to Mike Power: "Matthews... became aware of a need to expand the paper's appeal beyond the largely male, industrial, working-class readership implied by its title, and, in April 1966, led its relaunch as the Morning Star. Increasing its interest for women, students and professional people - achieved by covering a wider range of topics and better use of pictures and cartoons - resulted in an immediate circulation increase to 100,000, though a substantial part of that figure represented subsidised sales to Soviet-bloc countries." (140)

In January 1968 the Czechoslovak Party Central Committee passed a vote of no confidence in Antonin Novotny and he was replaced by Alexander Dubcek as party secretary. Soon afterwards Dubcek made a speech where he stated: "We shall have to remove everything that strangles artistic and scientific creativeness." During the next few weeks Dubcek announced a series of reforms. This included the abolition of censorship and the right of citizens to criticize the government. Dubcek described this as "socialism with a human face". (141)

Newspapers began publishing revelations about corruption in high places. This included stories about Novotny and his son. On 22nd March 1968, Novotny resigned as president of Czechoslovakia. He was now replaced by a Dubcek supporter, Ludvik Svoboda. The following month the Communist Party Central Committee published a detailed attack on Novotny's government. This included its poor record concerning housing, living standards and transport. It also announced a complete change in the role of the party member. It criticized the traditional view of members being forced to provide unconditional obedience to party policy. Instead it declared that each member "has not only the right, but the duty to act according to his conscience." The new reform programme included the creation of works councils in industry, increased rights for trade unions to bargain on behalf of its members and the right of farmers to form independent co-operatives. (142)

In July 1968 the Soviet leadership announced that it had evidence that the Federal Republic of Germany was planning an invasion of the Sudetenland and asked permission to send in the Red Army to protect Czechoslovakia. Alexander Dubcek, aware that the Soviet forces could be used to bring an end to Prague Spring, declined the offer. On 21st August, 1968, Czechoslovakia was invaded by members of the Warsaw Pact countries. In order to avoid bloodshed, the Czech government ordered its armed forces not to resist the invasion. Dubcek and Svoboda were taken to Moscow and soon afterwards they announced that after "free comradely discussion" that Czechoslovakia would be abandoning its reform programme. (143)