David Lloyd George

David Lloyd George, the second child and the elder son of William George and Elizabeth Lloyd, was born in Chorlton-on-Medlock, on 17th January, 1863.

Lloyd George's father was the son of a farmer who had a desire to become a doctor or a lawyer. However, unable to afford the training, William George became a teacher. He wrote in his diary, "I cannot make up my mind to be a school master for life... I want to occupy higher ground somehow or other." (1)

William George married Elizabeth Lloyd, the daughter of a shoemaker, on 16th November 1859. He became a school teacher in Newchurch in Lancashire, but in 1863, he bought the lease of Bwlford, a smallholding of thirty acres near Haverfordwest. However, he died, from pneumonia aged forty-four, on 7th June, 1864. (2)

Elizabeth Lloyd, was only 36 years-old and as well as having two young children, Mary Ellen and David, she was also pregnant with a third child. Elizabeth sent a telegram to her unmarried brother, Richard Lloyd, who was a master-craftsman with a shoe workshop in Llanystumdwy, Caernarvonshire. He arranged for the family to live with him. According to Hugh Purcell: "Richard Lloyd... was an aoto-didact whose light burned long into the night as he sought self-improvement. He ran the local debating society and regarded politics as a public service to improve people's lives." (3)

The Lloyd family were staunch Nonconformists and worshipped at the Disciples of Christ Chapel in Criccieth. Richard Lloyd was Welsh-speaking and deeply resented English dominance over Wales. Richard was impressed by David's intelligence and encouraged him in everything he did. David's younger brother, William George, later recalled: "He (David) was the apple of Uncle Lloyd's eye, the king of the castle and, like the other king, could do no wrong... Whether this unrestrained admiration was wholly good for the lad upon whom it was lavished, and indeed for the man who evolved out of him, is a matter upon which opinions may differ." (4)

David Lloyd George acknowledged the help given to him by Richard Lloyd: "All that is best in life's struggle I owe to him first... I should not have succeeded even so far as I have were it not for the devotion and shrewdness with which he has without a day's flagging kept me up to the mark... How many times have I done things... entirely because I saw from his letters that he expected me to do them." (5)

Lloyd George was an intelligent boy and did very well at his local school. Lloyd George's headmaster, David Evans, was described as a "teacher superlative quality". His "outstanding gift was for holding the attention of the young and for arousing their enthusiasm". Lloyd George said that "no pupil ever had a finer teacher". Evans returned the compliment: "no teacher ever had a more apt pupil". (6)

In 1877 Lloyd George decided he wanted to be a lawyer. After passing his Law Preliminary Examination he found a post at a firm of solicitors in Portmadog. He started work soon after his sixteenth birthday. He passed his final law examination in 1884 with a third-class honours and established his own law practice in Criccieth. He soon developed a reputation as a solicitor who was willing to defend people against those in authority. (7)

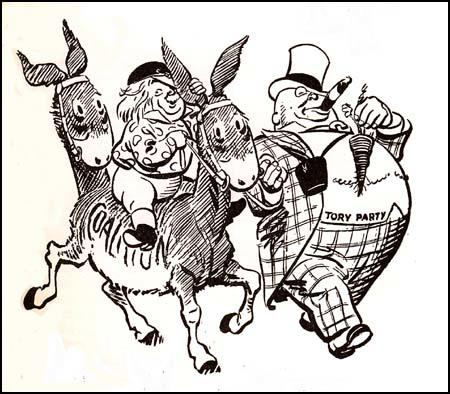

Lloyd George began getting involved in politics. His uncle was a member of the Liberal Party with a strong hatred of the Conservative Party. At the age of 18 he visited the House of Commons and noted in his diary: "I will not say that I eyed the assembly in a spirit similar to that in which William the Conqueror eyed England on his visit to Edward the Confessor, as the region of his future domain." (8)

In 1888 Lloyd George married Margaret Owen , the daughter of a prosperous farmer. He developed a "deserved reputation for promiscuity". One of his biographers has pointed out: "Not for nothing was his nickname the Goat. He had a high sex drive without the furtiveness that often goes with it. Although he knew that the fast life, as he called it, could ruin his career he took extraordinary risks. Only two years after his marriage he had an affair with an attractive widow of Caernavon, Mrs Jones... She gave birth to a son who grew up to look remarkably like Richard, Lloyd George's legitimate son who was born the previous year." (9)

Lloyd George joined the local Liberal Party and became an alderman on the Caernarvon County Council. He also took part in several political campaigns including one that attempted to bring an end to church tithes. Lloyd George was also a strong supporter of land reform. As a young man he had read books by Thomas Spence, John Stuart Mill and Henry George on the need to tackle this issue. He had also been impressed by pamphlets written by George Bernard Shaw and Sidney Webb of the Fabian Society on the need to tackle the issue of land ownership.

In 1890 Lloyd George was selected as the Liberal candidate for the Caernarvon Borough constituency. A by-election took place later that year when the sitting Conservative MP died. Lloyd George fought the election on a programme which called for religious equality in Wales, land reform, the local veto in granting licenses for the sale of alcohol, graduated taxation and free trade. Lloyd George won the seat by 18 votes and at twenty-seven became the youngest member of the House of Commons. (10)

The Boer War

The Boers (Dutch settlers in South Africa), under the leadership of Paul Kruger, resented the colonial policy of Joseph Chamberlain and Alfred Milner which they feared would deprive the Transvaal of its independence. After receiving military equipment from Germany, the Boers had a series of successes on the borders of Cape Colony and Natal between October 1899 and January 1900. Although the Boers only had 88,000 soldiers, led by the outstanding soldiers such as Louis Botha, and Jan Smuts, the Boers were able to successfully besiege the British garrisons at Ladysmith, Mafeking and Kimberley. On the outbreak of the Boer War, the conservative government announced a national emergency and sent in extra troops. (11)

Asquith called for support for the government and "an unbroken front" and became known as a "Liberal Imperialist". Campbell-Bannerman disagreed with Asquith and refused to to endorse the despatch of ten thousand troops to South Africa as he thought the move "dangerous when the the government did not know what it might lead to". David Lloyd George also disagreed with Asquith and complained that this was a war that had been started by Joseph Chamberlain, the Colonial Secretary. (12)

It has been claimed that Lloyd George "sympathised with the Boers, seeing them as a pastoral community like Welshmen before the industrial revolution". He supported their claim for independence under his slogan "Home Rule All Round" assuming "it would lead to a free association within the British Empire". He argued that the Boers "would only be subdued after much suffering, cruelty and cost." (13)

Lloyd George also saw this anti-war campaign as an opportunity to stop Asquith becoming the next leader of the Liberals. Lloyd George was on the left of the party and had been campaigning with little success for the introduction of old age pensions. The idea had been rejected by the Conservative government as being "too expensive". In one speech he made the point: "The war, I am told, has already cost £16,000,000 and I ask you to compare that sum with what it would cost to fund the old age pension schemes.... when a shell exploded it carried away an old age pension and the only satisfaction was that it killed 200 Boers - fathers of families, sons of mothers. Are you satisfied to give up your old age pension for that?" (14)

The overwhelmingly majority of the public remained fervently jingoistic. David Lloyd George came under increasing attack and after a speech at Bangor on 4th April 1900, he was interrupted throughout his speech, and after the meeting, as he was walking away, he was struck over the head with a bludgeon. His hat took the impact and although stunned, he was able to take refuge in a cafe, guarded by the police.

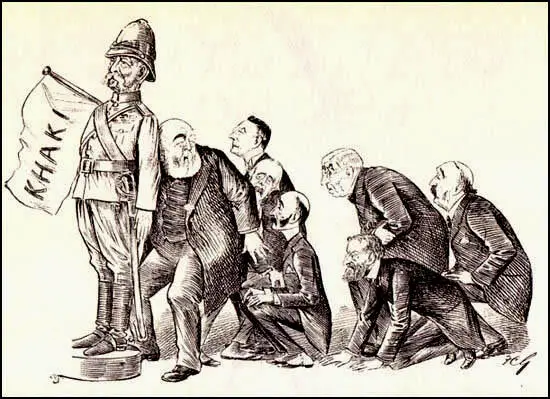

On 5th July, 1900, at a meeting addressed by Lloyd George in Liskeard ended in pandemonium. Around fifty "young roughs stormed the platform and occupied part of it, while a soldier in khaki was carried shoulder-high from end to end of the hall and ladies in the front seats escaped hurriedly by way of the platform door." Lloyd George tried to keep speaking and it was only when some members of the audience began throwing chairs at him that he left the hall. (15)

On 25th July, a motion on the Boer War, caused a three way split in the Liberal Party. A total of 40 "Liberal Imperialists" that included H. H. Asquith, Edward Grey, Richard Haldane and Archibald Primrose, Lord Rosebery, supported the government's policy in South Africa. Henry Campbell-Bannerman and 34 others abstained, whereas 31 Liberals, led by Lloyd George voted against the motion.

Robert Cecil, the Marquess of Salisbury, decided to take advantage of the divided Liberal Party and on 25th September 1900, he dissolved Parliament and called a general election. Lloyd George, admitted in one speech he was in a minority but it was his duty as a member of the House of Commons to give his constituents honest advice. He went on to make an attack on Tory jingoism. "The man who tries to make the flag an object of a single party is a greater traitor to that flag than the man who fires upon it." (16)

Henry Campbell-Bannerman with a difficult task of holding together the strongly divided Liberal Party and they were unsurprisingly defeated in the 1900 General Election. The Conservative Party won 402 seats against the 183 achieved by Liberal Party. However, anti-war MPs did better than those who defended the war. David Lloyd George increased the size of his majority in Caernarvon Borough. Other anti-war MPs such as Henry Labouchere and John Burns both increased their majorities. In Wales, of ten Liberal candidates hostile to the war, nine were returned, while in Scotland every major critic was victorious.

John Grigg argues that it was not the anti-war Liberals who lost the party the election. "The Liberals were beaten because they were disunited and hopelessly disorganised. The war certainly added to their confusion, but this was already so flagrant that they were virtually bound to lose, war or no war. The government also had the advantage of improved trade since 1895, which the war, admittedly, turned into a boom. All things considered, the Liberals did remarkably well." (17)

Emily Hobhouse, formed the Relief Fund for South African Women and Children in 1900. It was an organisation set up: "To feed, clothe, harbour and save women and children - Boer, English and other - who were left destitute and ragged as a result of the destruction of property, the eviction of families or other incidents resulting from the military operations". Except for members of the Society of Friends, very few people were willing to contribute to this fund. (18)

Hobhouse arrived in South Africa on 27th December, 1900. Hobhouse argued that Lord Kitchener's "Scorched Earth" policy included the systematic destruction of crops and slaughtering of livestock, the burning down of homesteads and farms, and the poisoning of wells and salting of fields - to prevent the Boers from resupplying from a home base. Civilians were then forcibly moved into the concentration camps. Although this tactic had been used by Spain (Ten Years' War) and the United States (Philippine-American War), it was the first time that a whole nation had been systematically targeted. She pointed this out in a report that she sent to the government led by Robert Cecil, the Marquess of Salisbury. (19)

When she returned to England, Hobhouse campaigned against the British Army's scorched earth and concentration camp policy. William St John Fremantle Brodrick, the Secretary of State for War argued that the interned Boers were "contented and comfortable" and stated that everything possible was being done to ensure satisfactory conditions in the camps. David Lloyd George took up the case in the House of Commons and accused the government of "a policy of extermination" directed against the Boer population. (20)

After meeting Hobhouse, Henry Campbell-Bannerman, gave his support to Lloyd George against Asquith and the Liberal Imperialists on the subject of the Boer War. In a speech to the National Reform Union he provided a detailed account of Hobhouse's report. He asked "When is a war not a war?" and then provided his own answer "When it is carried on by methods of barbarism in South Africa". (21)

The British action in South Africa grew increasingly unpopular and anti-war Liberal MPs and the leaders of the Labour Party saw it as an example of the worst excesses of imperialism. The Boer War ended with the signing of the Treaty of Vereeniging in May 1902. The peace settlement brought to an end the Transvaal and the Orange Free State as Boer republics. However, the British granted the Boers £3 million for restocking and repairing farm lands and promised eventual self-government. David Lloyd George commented: "They are generous terms for the Boers. Much better than those we offered them 15 months ago - after spending £50,000 in the meantime". (22)

1902 Education Act

On 24th March 1902, Arthur Balfour presented to the House of Commons an Education Bill that attempted to overturn the 1870 Education Act that had been brought in by William Gladstone. It had been popular with radicals as they were elected by ratepayers in each district. This enabled nonconformists and socialists to obtain control over local schools.

The new legislation abolished all 2,568 school boards and handed over their duties to local borough or county councils. These new Local Education Authorities (LEAs) were given powers to establish new secondary and technical schools as well as developing the existing system of elementary schools. At the time more than half the elementary pupils in England and Wales. For the first time, as a result of this legislation, church schools were to receive public funds. (23)

Nonconformists and supporters of the Liberal and Labour parties campaigned against the proposed act. David Lloyd George led the campaign in the House of Commons as he resented the idea that Nonconformists contributing to the upkeep of Anglican schools. It was also argued that school boards had introduced more progressive methods of education. "The school boards are to be destroyed because they stand for enlightenment and progress." (24)

In July, 1902, a by-election at Leeds demonstrated what the education controversy was doing to party fortunes, when a Conservative Party majority of over 2,500 was turned into a Liberal majority of over 750. The following month a Baptist came near to capturing Sevenoaks from the Tories and in November, 1902, Orkney and Shetland fell to the Liberals. That month also saw a huge anti-Bill rally held in London, at Alexandra Palace. (25)

Despite the opposition the Education Act was passed in December, 1902. John Clifford, the leader of the Baptist World Alliance, wrote several pamphlets about the legislation that had a readership that ran into hundreds of thousands. Balfour accused him of being a victim of his own rhetoric: "Distortion and exaggeration are of its very essence. If he has to speak of our pending differences, acute no doubt, but not unprecedented, he must needs compare them to the great Civil War. If he has to describe a deputation of Nonconformist ministers presenting their case to the leader of the House of Commons, nothing less will serve him as a parallel than Luther's appearance before the Diet of Worms." (26)

Clifford formed the National Passive Resistance Committee and over the next four years 170 men went to prison for refusing to pay their school taxes. This included 60 Primitive Methodists, 48 Baptists, 40 Congregationalists and 15 Wesleyan Methodists. The father of Kingsley Martin, was one of those who refused to pay: "Each year father and the other resisters all over the country refused to pay their rates for the upkeep of Church Schools. The passive resistors thought the issue of principle paramount and annually surrendered their goods instead of paying their rates. I well remember how each year one or two of our chairs and a silver teapot and jug were put out on the hall table for the local officers to take away. They were auctioned in the Market Place and brought back to us." (27)

David Lloyd George made clear that this was a terrible way to try and change people's opinions: "There is no greater tactical mistake possible than to prosecute an agitation against an injustice in such a way as to alienate a large number of men who, whilst they resent that injustice as keenly as anyone, either from tradition or timidity to be associated with anything savouring of revolutionary action. Such action should always be the last desperate resort of reformers... The interests of a whole generation of children will be sacrificed. It is not too big a price to pay for freedom, if this is the only resource available to us. But is it? I think not. My advice is, let us capture the enemy's artillery and turn his guns against him." (28)

Free Trade

Arthur Balfour became prime minister in June 1902. With the Liberal Party divided over the issue of the British Empire, it appeared that their chances of regaining office in the foreseeable future seemed remote. Then on 15th May 1903, Joseph Chamberlain, the Colonial Secretary, exploded a political bombshell with a speech in Birmingham advocating a system of preferential colonial tariffs. Asquith was convinced that Chamberlain had made a serious political mistake and after reading a report of the speech in The Times he told his wife: "Wonderful news today and it is only a question of time when we shall sweep the country". (29)

Asquith saw his opportunity and pointed out in speech after speech that a system of "preferential colonial tariffs" would mean taxes on food imported from outside the British Empire. Colin Clifford has pointed out: "Chamberlain had picked the one issue guaranteed to split the Unionist and unite the Liberals in the defence of Free Trade. The topic was tailor-made for Asquith and the next few months he shadowed Chamberlain's every speech, systematically tearing his argument to shreds. The Liberals were on the march again." (30)

As well as uniting the Liberal Party it created a split in the Conservative Party as several members of the cabinet believed strongly in Free Trade, including Charles T. Richie, the Chancellor of the Exchequer. Leo Amery argued: "The Birmingham speech was a challenge to free trade as direct and provocative as the theses which Luther nailed to the church door at Wittenberg." (31)

Arthur Balfour now began to have second thoughts on this policy and warned Joseph Chamberlain about the impact on the electorate in the next general election: "The prejudice against a small tax on food is not the fad of a few imperfectly informed theorists, it is a deep rooted prejudice affecting a large mass of voters, especially the poorest class, which it will be a matter of extreme difficulty to overcome." (32)

Asquith made speeches that attempted to frighten the growing working-class electorate "to whom cheap food had been a much cherished boon for the last quarter of a century and it annoyed the middle class who saw the prospect of a reduction in the purchasing power of their fixed incomes." As well as splitting the Conservative Party it united "the Liberals who had been hitherto hopelessly divided on all the main political issues." (33)

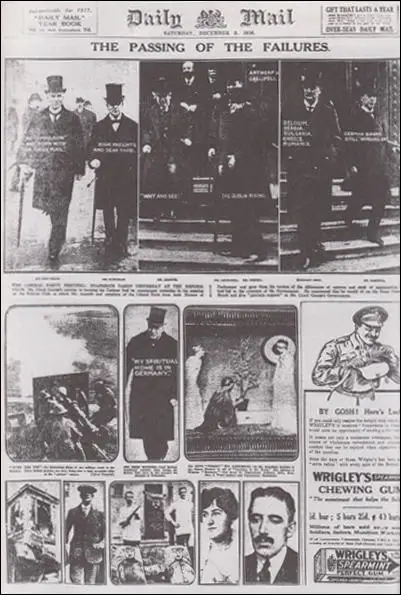

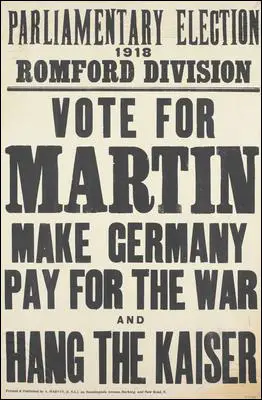

Arthur Balfour resigned on 4th December 1905. Henry Campbell-Bannerman refused to form a minority government and called a general election. On 21st December, 1905, Campbell-Bannerman made pledges to support Irish Home Rule, to cut defence spending, to repeal the 1902 Education Act, to oppose food taxes and slavery in South Africa. The Daily Mail reported that the Liberal Party intended to "attack capital, assail private enterprise, undo the Union, reverse the Education Act, cripple the one industry of South Africa, reduce the navy and weaken the army." It went on to say that if the Liberals won power it would bring a halt to the growth of the British Empire. (34)

1906 General Election

The 1906 General Election took place the following month. The Liberal Party won 397 seats (48.9%) compared to the Conservative Party's 156 seats (43.4%). The Labour Party, led by Keir Hardie did well, increasing their seats from 2 to 29. In the landslide victory Balfour lost his seat as did most of his cabinet ministers. Margot Asquith wrote: "When the final figures of the Elections were published everyone was stunned, and it certainly looks as if it were the end of the great Tory Party as we have known it." (35)

Henry Campbell-Bannerman appointed David Lloyd George as President of the Board of Trade. He was seen as a very effective minister. George Riddell commented. "I think his executive powers his strong point. His courage, patience, tenacity, energy, tact, industry, power of work, and eloquence combine to make him an administrator of the first order. And to these should be added his charm of manner, his power of observation, and his ruthless method of dismissing inefficients. These qualities are especially valuable at a time of emergency like the present. He sees something to be done, and he does it well and quickly. His schemes are another matter." (35a)

Campbell-Bannerman suffered a severe stroke in November, 1907. He returned to work following two months rest but it soon became clear that the 71 year-old prime minister was unable to continue. On 27th March, 1908, he asked to see H. H. Asquith. According to Margot Asquith: "Henry came into my room at 7.30 p.m. and told me that Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman had sent for him that day to tell him that he was dying... He began by telling him the text he had chosen out of the Psalms to put on his grave, and the manner of his funeral... Henry was deeply moved when he went on to tell me that Campbell-Bannerman had thanked him for being a wonderful colleague." (41)

Campbell-Bannerman suggested to Edward VII that Asquith should replace him as Prime Minister. However, the King with characteristic selfishness was reluctant to break his holiday in Biarritz and ordered him to continue. On 1st April, the dying Campbell-Bannerman, sent a letter to the King seeking his permission to give up office. He agreed as long as Asquith was willing to travel to France to "kiss hands". Colin Clifford has argued that "Campbell-Bannerman... for all his defects, was probably the most decent man ever to hold the office of Prime Minister. Childless and a widower since the death of his beloved wife the year before, he was now facing death bravely, with no family to comfort him." Cambell-Bannerman died later that month. (42)

H. H. Asquith appointed David Lloyd George as his Chancellor of the Exchequer. Other members of his team included Winston Churchill (Board of Trade), Herbert Gladstone (Home Secretary), Charles Trevelyan (Board of Education), Richard Haldane (Secretary of State for War), Reginald McKenna (First Lord of the Admiralty) and John Burns (President of the Local Government Board).

Asquith took a gamble when he appointed Lloyd George to such a senior position. He was far to the left of Asquith but he reasoned that a disgruntled Lloyd George would be less of a problem inside the government as out. Asquith wrote: "The offer which I make is a well-deserved tribute to your long and eminent service to our party and to the splendid capacity which you have shown in your administration of the Board of Trade." (43)

David Lloyd George in one speech had warned that if the Liberal Party did not pass radical legislation, at the next election, the working-class would vote for the Labour Party: "If at the end of our term of office it were found that the present Parliament had done nothing to cope seriously with the social condition of the people, to remove the national degradation of slums and widespread poverty and destitution in a land glittering with wealth, if they do not provide an honourable sustenance for deserving old age, if they tamely allow the House of Lords to extract all virtue out of their bills, so that when the Liberal statute book is produced it is simply a bundle of sapless legislative faggots fit only for the fire - then a new cry will arise for a land with a new party, and many of us will join in that cry." (44)

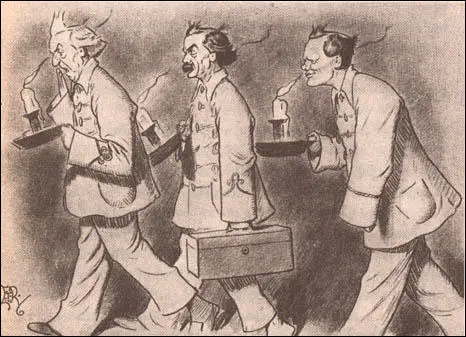

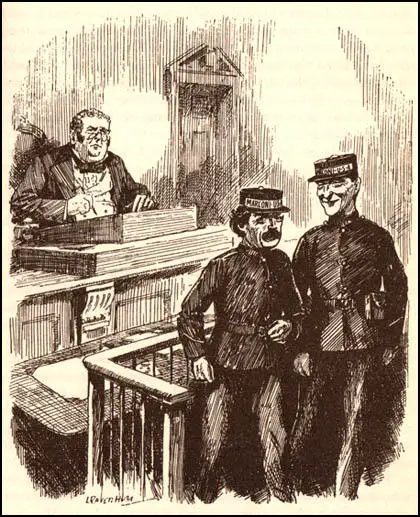

and Winston Churchill in their pyjamas working late at night in their

attempt to pass radical legislation to improve the life of the poor.

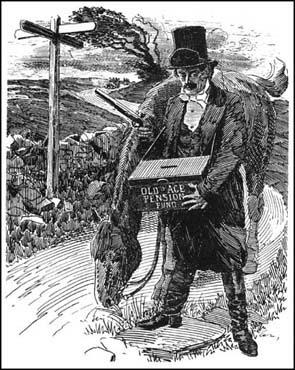

Lloyd George had been a long opponent of the Poor Law in Britain. He was determined to take action that in his words would "lift the shadow of the workhouse from the homes of the poor". He believed the best way of doing this was to guarantee an income to people who were to old to work. Based on the ideas of Tom Paine that first appeared in his book Rights of Man, Lloyd George's proposed the introduction of old age pensions.

In a speech on 15th June 1908, he pointed out: "You have never had a scheme of this kind tried in a great country like ours, with its thronging millions, with its rooted complexities... This is, therefore, a great experiment... We do not say that it deals with all the problem of unmerited destitution in this country. We do not even contend that it deals with the worst part of that problem. It might be held that many an old man dependent on the charity of the parish was better off than many a young man, broken down in health, or who cannot find a market for his labour." (45)

However, the Labour Party was disappointed by the proposal. Along with the Trade Union Congress they had demanded a pension of at least five shillings a week for everybody of sixty or over, Lloyd George's scheme gave five shillings a week to individuals over seventy; and for couples the pension was to be 7s. 6d. Moreover, even among the seventy-year-olds not everyone was to qualify; as well as criminals and lunatics, people with incomes of more than £26 a year (or £39 a year in the case of couples) and people who would have received poor relief during the year prior to the scheme's coming into effect, were also disqualified." (46)

The People's Budget

To pay for these pensions Lloyd George had to raise government revenues by an additional £16 million a year. In 1909 Lloyd George announced what became known as the People's Budget. This included increases in taxation. Whereas people on lower incomes were to pay 9d. in the pound, those on annual incomes of over £3,000 had to pay 1s. 2d. in the pound. Lloyd George also introduced a new super-tax of 6d. in the pound for those earning £5,000 a year. Other measures included an increase in death duties on the estates of the rich and heavy taxes on profits gained from the ownership and sale of property. Other innovations in Lloyd George's budget included labour exchanges and a children's allowance on income tax. (47)

David Lloyd George had based his ideas on the reforms introduced by Otto von Bismarck in the 1880s. As The Contemporary Review reported: "English progressives have decided to take a leaf out of the book of Bismarck who dealt the heaviest blow against German socialism not by laws of oppression... but by the great system of state insurance which now safeguards the German workmen at almost every point of his industrial career." (47a)

Archibald Primrose, Lord Rosebery, the former Liberal Party leader, stated that: "The Budget, was not a Budget, but a revolution: a social and political revolution of the first magnitude... To say this is not to judge it, still less to condemn it, for there have been several beneficent revolutions." However, he opposed the Budget because it was "pure socialism... and the end of all, the negation of faith, of family, of property, of Monarchy, of Empire." (48)

Ramsay MacDonald argued that the Labour Party should fully support the budget. "Mr. Lloyd George's Budget, classified property into individual and social, incomes into earned and unearned, and followers more closely the theoretical contentions of Socialism and sound economics than any previous Budget has done." MacDonald went on to argue that the House of Lords should not attempt to block this measure. "The aristocracy... do not command the moral respect which tones down class hatreds, nor the intellectual respect which preserves a sense of equality under a regime of considerable social differences." (49)

David Lloyd George admitted that he would never have got his proposals through the Cabinet without the strong support of Asquith. He told his brother: "Budgeting all day... the Cabinet was very divided... Prime Minister decided in my favour to my delight". He told a friend: "The Prime Minister has backed me up through thick and thin with splendid loyalty. I have the deepest respect for him and he has real sympathy for the ordinary and the poor." (50)

His other main supporter in the Cabinet was Winston Churchill. He spoke at a large number of public meetings of the pressure group he formed, the Budget League. Churchill rarely missed a debate on the issue and one newspaper report suggested that he had attended one late night debate in the House of Commons in his pajamas. Some historians have claimed that both men were using the measure to further their political careers. Lloyd George admitted that he would never have got his proposals through the Cabinet without the strong support of Herbert Asquith and Winston Churchill. He spoke at a large number of public meetings of the pressure group he formed, the Budget League. Churchill rarely missed a debate on the issue and one newspaper report suggested that he had attended one late night debate in the House of Commons in his pajamas. Lloyd George told a close friend: "I should say that I have Winston Churchill with me in the Cabinet, and above all the Prime Minister has backed me up through thick and thin with splendid loyalty." (50a)

Robert Lloyd George, the author of David & Winston: How a Friendship Changed History (2005) has suggested that their main motive was to prevent socialism in Britain: "Churchill and Lloyd George intuitively saw the real danger of socialism in the global situation of that time, when economic classes were so divided. In other European countries, revolution would indeed sweep away monarchs and landlords within the next ten years. But thanks to the reforming programme of the pre-war Liberal government, Britain evolved peacefully towards a more egalitarian society. It is arguable that the peaceful revolution of the People's Budget prevented a much more bloody revolution." (51)

The Conservatives, who had a large majority in the House of Lords, objected to this attempt to redistribute wealth, and made it clear that they intended to block these proposals. Lloyd George reacted by touring the country making speeches in working-class areas on behalf of the budget and portraying the nobility as men who were using their privileged position to stop the poor from receiving their old age pensions. The historian, George Dangerfield, has argued that Lloyd George had created a budget that would destroy the House of Lords if they tried to block the legislation: "It was like a kid, which sportsmen tie up to a tree in order to persuade a tiger to its death." (52)

Charles Hobhouse helped Lloyd George to get his People's Budget though Parliament. He recorded in his diary: "I asked Lloyd George what he really wanted, the Budget to pass, or be rejected, and suggested that the author of a successful financial scheme such as his was far more likely to go down to posterity than one who was Chancellor of the Exchequer merely... He agreed but added that he might be remembered even better as one who had upset the hereditary House of Lords." (52a)

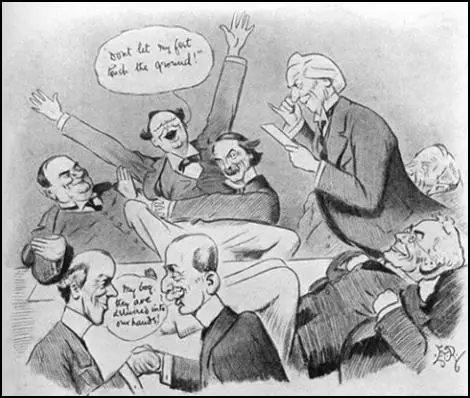

House of Lords: from top left, clockwise: Richard Haldane, Winston Churchill,

David Lloyd George, H. H. Asquith, John Morley, Augustine Birrell,

Robert Crewe-Milnes and Reginald McKenna. (1909)

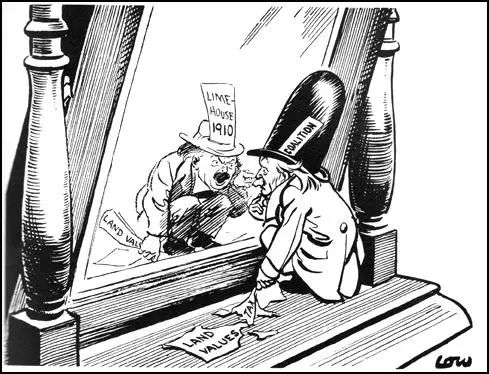

Asquith's strategy was to offer the peers the minimum of provocation and hope to finesse them into passing the legislation. Lloyd George had a different style and in a speech on 30th July, 1909, in the working-class district of Limehouse in London on the selfishness of rich men unwilling "to provide for the sick and the widows and orphans". He concluded his speech with the threat that if the peers resisted, they would be brushed aside "like chaff before us". (53)

Edward VII was furious and suggested to Asquith that Lloyd George was a "revolutionary" and a "socialist". Asquith explained that the support of the King was vital if the House of Lords was to be outmanoeuvred. Asquith explained to Lloyd George that the King "sees in the general tone, and especially in the concluding parts, of your speech, a menace to property and a Socialistic spirit". He added it was important "to avoid alienating the King's goodwill... and... what is needed is reasoned appeal to moderate and reasonable men" and not to "rouse the suspicions and fears of the middle class". (54)

David Lloyd George made another speech attacking the House of Lords on 9th October, 1909: "Let them realize what they are doing. They are forcing a Revolution. The Peers may decree a Revolution, but the People will direct it. If they begin, issues will be raised that they little dream of. Questions will be asked which are now whispered in humble voice, and answers will be demanded with authority. It will be asked why 500 ordinary men, chosen accidentally from among the unemployed, should override the judgment - the deliberate judgment - of millions of people who are engaged in the industry which makes the wealth of the country. It will be asked who ordained a few should have the land of Britain as a perquisite? Who made ten thousand people owners of the soil, and the rest of us trespassers in the land of our birth? Where did that Table of the law come from? Whose finger inscribed it? These are questions that will be asked. The answers are charged with peril for the order of things that the Peers represent. But they are fraught with rare and refreshing fruit for the parched lips of the multitude, who have been treading along the dusty road which the People have marked through the Dark Ages, that are now emerging into the light." (55)

It was clear that the House of Lords would block the budget. Asquith asked the King to create a large number of Peers that would give the Liberals a majority. Edward VII refused and his private secretary, Francis Knollys, wrote to Asquith that "to create 570 new Peers, which I am told would be the number required... would practically be almost an impossibility, and if asked for would place the King in an awkward position". (56)

On 30th November, 1909, the Peers rejected the Finance Bill by 350 votes to 75. Asquith had no option but to call a general election. In January 1910, the Liberals lost votes and was forced to rely on the support of the 42 Labour Party MPs to govern. Asquith increased his own majority in East Fife but he was prevented from delivering his acceptance speech by members of the Women Social & Political Union who were demanding "Votes for Women". (57)

John Grigg, the author of The People's Champion (1978) argues that the reason why the "people failed to give a sweeping, massive endorsement to the People's Budget" was that the electorate in 1910 was "by no means representative of the whole British nation". He points out that "only 58 per cent of adult males had the vote, and it is a fair assumption that the remaining 42 per cent would, if enfranchised, have voted in very large numbers for Liberal or Labour candidates. In what was still a disproportionately middle-class electorate the fear of Socialism was strong, and many voters were susceptible to the argument that the Budget was a first installment of Socialism." (58)

Some of his critics on the left of the party believed that Asquith had not mounted a more aggressive campaign against the House of Lords. It was argued that instead of threatening its power to veto legislation, he should have advocated making it a directly elected second chamber. Asquith felt this was a step to far and was more interested in a negotiated settlement. However, to Colin Clifford, this made Asquith look "weak and indecisive". (59)

In a speech on 21st February, 1910, Asquith outlined his plans for reform: "Recent experience has disclosed serious difficulties due to recurring differences of strong opinion between the two branches of the Legislature. Proposals will be laid before you, with convenient speed, to define the relations between the Houses of Parliament, so as to secure the undivided authority of the House of Commons over finance and its predominance in legislation." (60)

The Parliament Bill was introduced later that month. "Any measure passed three times by the House of Commons would be treated as if it had been passed by both Houses, and would receive the Royal Assent... The House of Lords was to be shorn absolutely of power to delay the passage of any measure certified by the Speaker of the House of Commons as a money bill, but was to retain the power to delay any other measure for a period of not less than two years." (61)

Edward VII died in his sleep on 6th May 1910. His son, George V, now had the responsibility of dealing with this difficult constitutional question. David Lloyd George had a meeting with the new king and had an "exceedingly frank and satisfactory talk about the political crisis". He told his wife that he was not very intelligent as "there's not much in his head". However, he "expressed the desire to try his hand at conciliation... whether he will succeed is somewhat doubtful." (62)

James Garvin, the editor of The Observer, argued it was time that the government reached a negotiated settlement with the House of Lords: "If King Edward upon his deathbed could have sent a last message to his people, he would have asked us to lay party passion aside, to sign a truce of God over his grave, to seek... some fair means of making a common effort for our common country... Let conference take place before conflict is irrevocably joined." (63)

A Constitutional Conference was established with eight members, four cabinet ministers and four representatives from the Conservative Party. Over the next six months the men met on twenty-one occasions. However, they never came close to an agreement and the last meeting took place in November. George Barnes, the Labour Party MP, called for an immediate creation of left-wing peers. However, when a by-election at Walthamstow suggested a slight swing to the Liberals, Asquith decided to call another General Election. (64)

David Lloyd George called on the British people to vote for a change in the parliamentary system: "How could anyone defend the Constitution in its present form? No country in the world would look at our system - no free country, I mean... France has a Senate, the United States has a Senate, the Colonies have Senates, but they are all chosen either directly or indirectly by the people." (65)

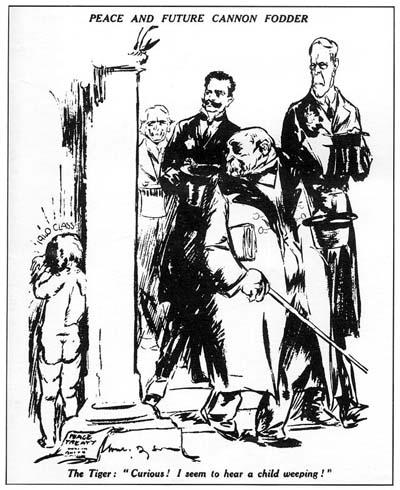

The general election of December, 1910, produced a House of Commons which was almost identical to the one that had been elected in January. The Liberals won 272 seats and the Conservatives 271, but the Labour Party (42) and the Irish (a combined total of 84) ensured the government's survival as long as it proceeded with constitutional reform and Home Rule. (66)

The Parliament Bill, which removed the peers' right to amend or defeat finance bills and reduced their powers from the defeat to the delay of other legislation, was introduced into the House of Commons on 21st February 1911. It completed its passage through the Commons on 15th May. A committee of the House of Lords then amended the bill out of all recognition. (67)

It now looked like that H. H. Asquith would now persuade George V to appoint a large number of Liberal peers. Lord Northcliffe, who had used his newspaper empire, to support the House of Lords, wrote that he was frightened that the King was about to turn the Lords into a "Radical body". He added: "I do not think the House of Lords is particularly popular with anybody and there certainly are lots of people in the lower middle class who would like to see it smashed - quite forgetting it is the only barrier they have against the growth of socialist taxation." (68)

According to Lucy Masterman, the wife of Charles Masterman, the Liberal MP for West Ham North, that David Lloyd George had a secret meeting with Arthur Balfour, the leader of the Conservative Party. Lloyd George had bluffed Balfour into believing that George V had agreed to create enough Liberal supporting peers to pass a new Parliament Bill. (69)

Although a list of 249 candidates for ennoblement, including Thomas Hardy, Bertrand Russell, Gilbert Murray and J. M. Barrie, had been drawn up, they had not yet been presented to the King. After the meeting Balfour told Conservative peers that to prevent the Liberals having a permanent majority in the House of Lords, they must pass the bill. On 10th August 1911, the Parliament Act was passed by 131 votes to 114 in the Lords. (70)

National Insurance Act

During his speech on the People's Budget, David Lloyd George, pointed out that Germany had a compulsory national insurance against sickness since 1884. He argued that he intended to introduce a similar system in Britain. With a reference to the arms race between Britain and Germany he commented: "We should not emulate them only in armaments." (71)

In December 1910 Lloyd George sent one of his Treasury civil servants, William J. Braithwaite, to Germany to make an up-to-date study of its State insurance system. On his return he had a meeting with Charles Masterman, Rufus Isaacs and John S. Bradbury. Braithwaite argued strongly that the scheme should be paid for by the individual, the state and the employer: "Working people ought to pay something. It gives them a feeling of self respect and what costs nothing is not valued." (72)

One of the questions that arose during this meeting was whether British national insurance should work, like the German system, on the "dividing-out" principle, or should follow the example of private insurance in accumulating a large reserve. Lloyd George favoured the first method, but Braithwaite fully supported the alternative system. (73) He argued: "If a fund divides out, it is a state club, and not an insurance. It has no continuity - no scientific basis - it lives from day to day. It is all very well when it is young and sickness is low. But as its age increases sickness increases, and the young men can go elsewhere for a cheaper insurance." (74)

The debate between the two men continued over the next two months. Lloyd George argued: "The State could not manage property or invest with wisdom. It would be very bad for politics if the State owned a huge fund. The proper course for the Chancellor of the Exchequer was to let money fructify in the pockets of the people and take it only when he wanted it." (75)

Eventually, in March, 1911, Braithwaite produced a detailed paper on the subject, where he explained that the advantage of a state system was the effect of interest on accumulative insurance. Lloyd George told Braithwaite that he had read his paper but admitted he did not understand it and asked him to explain the economics of his health insurance system. (76)

"I managed to convince him that one way or another it (interest) was, and had to be paid. It was at any rate an extra payment which young contributors could properly demand, and the State contribution must at least make it up to them if their contributions were to be taken off and used by the older people. After about half an hour's talk he went upstairs to dress for dinner." Later that night Lloyd George told Braithwaite that he was now convinced by his proposals. "Dividing-out was dead!" (77)

Braithwaite explained that the advantages of an accumulative state fund was the ability to use the insurance reserve to underwrite other social programmes. Lloyd George presented his national insurance proposal to the Cabinet at the beginning of April. "Insurance was to be made compulsory for all regularly employed workers over the age of sixteen and with incomes below the level - £160 a year - of liability for income tax; also for all manual labourers, whatever their income. The rates of contribution would be 4d. a week from a man, and 3d. a week from a woman; 3d. a week from his or her employer; and 2d. a week from the State." (78)

The slogan adopted by Lloyd George to promote the scheme was "9d for 4d". In return for a payment which covered less than half the cost, contributors were entitled to free medical attention, including the cost of medicine. Those workers who contributed were also guaranteed 10s. a week for thirteen weeks of sickness and 5s a week indefinitely for the chronically sick.

Braithwaite later argued that he was impressed by the way Lloyd George developed his policy on health insurance: "Looking back on these three and a half months I am more and more impressed with the Chancellor's curious genius, his capacity to listen, judge if a thing is practicable, deal with the immediate point, deferring all unnecessary decision and keeping every road open till he sees which is really the best. Working for any other man I must inevitably have acquiesced in some scheme which would not have been as good as this one, and I am very glad now that he tore up so many proposals of my own and other people which were put forward as solutions, and which at the time we had persuaded ourselves into thinking possible. It will be an enormous misfortune if this man by any accident should be lost to politics." (79)

The large insurance companies were worried that this measure would reduce the popularity of their own private health schemes. Lloyd George, arranged a meeting with the association that represented the twelve largest companies. Their chief negotiator was Kingsley Wood, who told Lloyd George, that in the past he had been able to muster enough support in the House of Commons to defeat any attempt to introduce a state system of widows' and orphans' benefits and so the government "would be wise to abandon the scheme at once." (80)

David Lloyd George was able to persuade the government to back his proposal of health insurance: "After searching examination, the Cabinet expressed warm and unanimously approval of the main and government principles of the scheme which they believed to be more comprehensive in its scope and more provident and statesmanlike in its machinery than anything that had hitherto been attempted or proposed." (81)

The National Insurance Bill was introduced into the House of Commons on 4th May, 1911. Lloyd George argued: "It is no use shirking the fact that a proportion of workmen with good wages spend them in other ways, and therefore have nothing to spare with which to pay premiums to friendly societies. It has come to my notice, in many of these cases, that the women of the family make most heroic efforts to keep up the premiums to the friendly societies, and the officers of friendly societies, whom I have seen, have amazed me by telling the proportion of premiums of this kind paid by women out of the very wretched allowance given them to keep the household together."

Lloyd George went on to explain: "When a workman falls ill, if he has no provision made for him, he hangs on as long as he can and until he gets very much worse. Then he goes to another doctor (i.e. not to the Poor Law doctor) and runs up a bill, and when he gets well he does his very best to pay that and the other bills. He very often fails to do so. I have met many doctors who have told me that they have hundreds of pounds of bad debts of this kind which they could not think of pressing for payment of, and what really is done now is that hundreds of thousands - I am not sure that I am not right in saying millions - of men, women and children get the services of such doctors. The heads of families get those services at the expense of the food of their children, or at the expense of good-natured doctors."

Lloyd George stated this measure was just the start to government involvement in protecting people from social evils: "I do not pretend that this is a complete remedy. Before you get a complete remedy for these social evils you will have to cut in deeper. But I think it is partly a remedy. I think it does more. It lays bare a good many of those social evils, and forces the State, as a State, to pay attention to them. It does more than that... till the advent of a complete remedy, this scheme does alleviate an immense mass of human suffering, and I am going to appeal, not merely to those who support the Government in this House, but to the House as a whole, to the men of all parties, to assist us." (82)

The Observer welcomed the legislation as "by far the largest and best project of social reform ever yet proposed by a nation. It is magnificent in temper and design". (83) The British Medical Journal described the proposed bill as "one of the greatest attempts at social legislation which the present generation has known" and it seemed that it was "destined to have a profound influence on social welfare." (84)

Ramsay MacDonald promised the support of the Labour Party in passing the legislation, but some MPs, including Fred Jowett, George Lansbury and Philip Snowden denounced it as a poll tax on the poor. Along with Keir Hardie, they wanted free sickness and unemployment benefit to be paid for by progressive taxation. Hardie commented that the attitude of the government was "we shall not uproot the cause of poverty, but we will give you a porous plaster to cover the disease that poverty causes." (85)

Lloyd George's reforms were strongly criticised and some Conservatives accused him of being a socialist. There was no doubt that he had been heavily influenced by Fabian Society pamphlets on social reform that had been written by Beatrice Webb, Sidney Webb and George Bernard Shaw. However, some Fabians "feared that the Trade Unions might now be turned into Insurance Societies, and that their leaders would be further distracted from their industrial work." (86)

Lloyd George pointed out that the labour movement in Germany had initially opposed national insurance: "In Germany, the trade union movement was a poor, miserable, wretched thing some years ago. Insurance has done more to teach the working class the virtue of organisation than any single thing. You cannot get a socialist leader in Germany today to do anything to get rid of that Bill... Many socialist leaders in Germany will say that they would rather have our Bill than their own." (87)

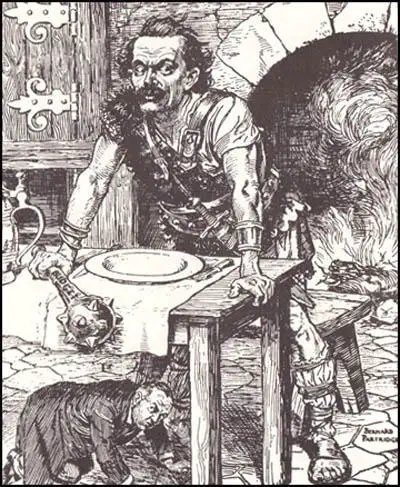

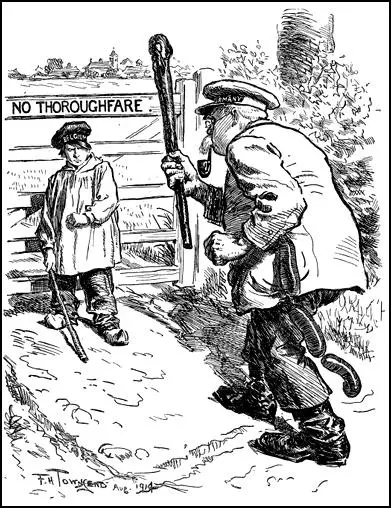

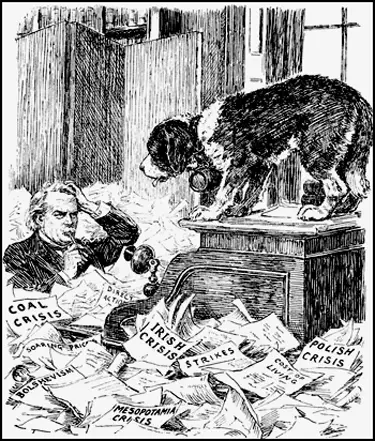

Patent Medicine: "Never mind, dear fellow, I'll stand by you - to the death!"

Alfred Harmsworth, Lord Northcliffe, launched a propaganda campaign against the bill on the grounds that the scheme would be too expensive for small employers. The climax of the campaign was a rally in the Albert Hall on 29th November, 1911. As Lord Northcliffe, controlled 40 per cent of the morning newspaper circulation in Britain, 45 per cent of the evening and 15 per cent of the Sunday circulation, his views on the subject was very important.

H. H. Asquith was very concerned about the impact of the The Daily Mail involvement in this issue: "The Daily Mail has been engineering a particularly unscrupulous campaign on behalf of mistresses and maids and one hears from all constituencies of defections from our party of the small class of employers. There can be no doubt that the Insurance Bill is (to say the least) not an electioneering asset." (88)

Frank Owen, the author of Tempestuous Journey: Lloyd George and his Life and Times (1954) suggested that it was those who employed servants who were the most hostile to the legislation: "Their tempers were inflamed afresh each morning by Northcliffe's Daily Mail, which alleged that inspectors would invade their drawing-rooms to check if servants' cards were stamped, while it warned the servants that their mistresses would sack them the moment they became liable for sickness benefit." (89)

The National Insurance Bill spent 29 days in committee and grew in length and complexity from 87 to 115 clauses. These amendments were the result of pressure from insurance companies, Friendly Societies, the medical profession and the trade unions, which insisted on becoming "approved" administers of the scheme. The bill was passed by the House of Commons on 6th December and received royal assent on 16th December 1911. (90)

Lloyd George admitted that he had severe doubts about the amendments: "I have been beaten sometimes, but I have sometimes beaten off the attack. That is the fortune of war and I am quite ready to take it. Honourable Members are entitled to say that they have wrung considerable concessions out of an obstinate, stubborn, hard-hearted Treasury. They cannot have it all their own way in this world. Let them be satisfied with what they have got. They are entitled to say this is not a perfect Bill, but then this is not a perfect world. Do let them be fair. It is £15,000,000 of money which is not wrung out of the workmen's pockets, but which goes, every penny of it, into the workmen's pocket. Let them bear that in mind. I think they are right in fighting for organisations which have achieved great things for the working classes. I am not at all surprised that they regard them with reverence. I would not do anything which would impair their position. Because in my heart I believe that the Bill will strengthen their power is one of the reasons why I am in favour of this Bill." (91)

The Daily Mail and The Times, both owned by Lord Northcliffe, continued its campaign against the National Insurance Act and urged its readers who were employers not to pay their national health contributions. David Lloyd George asked: "Were there now to be two classes of citizens in the land - one class which could obey the laws if they liked; the other, which must obey whether they liked it or not? Some people seemed to think that the Law was an institution devised for the protection of their property, their lives, their privileges and their sport it was purely a weapon to keep the working classes in order. This Law was to be enforced. But a Law to ensure people against poverty and misery and the breaking-up of home through sickness or unemployment was to be optional." (92)

Lloyd George attacked the newspaper baron for encouraging people to break the law and compared the issue to the foot-and-mouth plague rampant in the countryside at the time: "Defiance of the law is like the cattle plague. It is very difficult to isolate it and confine it to the farm where it has broken out. Although this defiance of the Insurance Act has broken out first among the Harmsworth herd, it has travelled to the office of The Times. Why? Because they belong to the same cattle farm. The Times, I want you to remember, is just a twopenny-halfpenny edition of The Daily Mail." (93)

Despite the opposition from newspapers and and the British Medical Association, the business of collecting contributions began in July 1912, and the payment of benefits on 15th January 1913. Lloyd George appointed Sir Robert Morant as chief executive of the health insurance system. William J. Braithwaite was made secretary to the joint committee responsible for initial implementation, but his relations with Morant were deeply strained. "Overworked and on the verge of a breakdown, he was persuaded to take a holiday, and on his return he was induced to take the post of special commissioner of income tax in 1913." (94)

Marconi Scandal

David Lloyd George, unlike most Liberal and Conservative MPs, "had no capital resources, whether self-made or derived from the money-making activities of ancestors... As a young M.P. he had to live off a share, perhaps unduly large, of the profits from the solicitors' firm in which he and his brother William were the founder-partners, supplemented by whatever fees he could earn from casual journalism and lecturing." John Grigg has argued that Lloyd George resented this, "not because he cared about money for its own sake, but because he could see that private wealth was a key to political independence". (95)

After becoming Chancellor of the Exchequer he received a salary of £5,000. Although he could live on this income he worried about what would happen if he lost office. He decided to use his contacts with businessmen to provide him with information that would enable to invest wisely in stocks and shares. His good friend and political supporter, George Cadbury, heard about these financial dealings and warned him that if the Conservative press found out about this it could bring an end to his political career. Cadbury was the owner of the Daily News and might have heard about this from journalists he employed.

"Those who hate you and your measures make themselves heard, but the millions who rejoice in your work and in the courage you have shown on behalf of labour, like myself, have no means of expressing their gratitude for what you have done - this must be my apology for writing to a man whose every moment is full of important business, but even now I would not write if I did not feel that I had a definite duty to convey to you my own desire which I believe represents that of millions, that you should hold fast your integrity." (96)

One of the reasons for this letter was the rumour that David Lloyd George had made £100,000 by buying and selling Surrey Commercial Dock shares. Surrey Commercial was one of the three London dock companies which had been created when the Port of London was being established, in 1908, under a scheme prepared by Lloyd George but enacted by his successor at the Board of Trade, Winston Churchill. (97)

Lloyd George wrote to his wife about his share dealings. "So you have only £50 to spare. Very well, I will invest it for you. Sorry you have no more available as I think it is quite a good thing I have got." (98) Four days later he told her about the success of his investments: "I got my cheque from my last Argentina Railway deal today. I have made £567. But the thing I have been talking to you about is a new thing." (99)

H. H. Asquith had been urged by senior members of the military to set up an British Empire chain of wireless telegraphy. Herbert Samuel, the Postmaster-General, began negotiating with several companies who could provide this service. This included the English Marconi Company, whose managing director was Godfrey Isaacs, the brother of Rufus Isaacs, the Attorney General.

Godfrey Isaacs, was also on the board of the Marconi Wireless Telegraph Company of America, that controlled the company operating in London. Isaacs had been given responsibility for selling 50,000 shares in the company to English investors before they became available to the general public. He advised his brother, Rufus Isaacs, to buy 10,000 of these shares at £2 apiece. He shared this information with Lloyd George and Alexander Murray, the Chief Whip, and they both purchased 1,000 shares at the same price. On 18th April 1912 Murray also bought 2,000 shares for the Liberal Party. (100)

These shares were not available on the British stock market. On 19th April, the first day that shares in the Marconi Company of America were available in London, the shares opened at £3 and ended the day at £4. The main reason for this was the news that Herbert Samuel was in negotiations with the English Marconi Company to provide a wireless-telegraphy system for the British Empire. Rufus Isaacs now sold all his shares for a profit of £20,000. Whereas his fellow government ministers, Lloyd George and Alexander Murray, sold half their shares and therefore got the other half for free. Lloyd George then used this money to buy another 1,500 shares in the company. (101)

Cecil Chesterton, G. K. Chesterton and Hilaire Belloc were involved with a new journal called The Eye-Witness. It was later pointed out that "the object of the Eye-Witness was to make the English public know and care about the perils of political corruption". The editor wrote to his mother, Lloyd George has been dealing on the Stock Exchange heavily to his advantage with private political information". They immediately began to investigate the case. (102)

On 19th July, 1912, Herbert Samuel announced that a contract had been agreed with the English Marconi Company. A couple of days later, W. R. Lawson, wrote in the weekly Outlook Magazine: "The Marconi Company has from its birth been a child of darkness... Its relations with certain Ministers have not always been purely official or political." (103)

Whereas the rest of the mainstream media ignored the story, over the next few weeks The Eye-Witness produced a series of articles on the subject. It suggested that Rufus Isaacs had made £160,000 out of the deal. It was also claimed that David Lloyd George, Godfrey Isaacs, Alexander Murray and Herbert Samuel had profited by buying shares based on knowledge of the government contract. (104)

The defenders of Lloyd George, Isaacs, Murray and Samuel, accused the magazine of anti-semitism, pointing out that three of the men named were Jewish. "They were all victims of the disease of the heart known as anti-semitism. It was a gift to them that the Attorney-General and his brother had the name of Isaacs, and the added bonus that the Postmaster General, who had negotiated the contract, was called Samuel." (105)

H. H. Asquith called a meeting with the accused men and discussed the possibility of legal action against the magazine. It was Asquith who eventually advised against this: "I suspect that Eyewitness has a very meagre circulation. I notice only one page of advertisements and then by Belloc's publishers. Prosecution would secure it notoriety which might yield subscribers." (106)

A debate on the Marconi contract took place on 11th October, 1912. Herbert Samuel explained that Marconi was the company best qualified to do the job and several Conservative MPs made speeches where they agreed with the government over this issue. The only dissenting voice was George Lansbury, the Labour MP, who argued that there had been "scandalous gambling in Marconi shares." (107)

David Lloyd George responded by attacking those who had spread untrue stories about his share dealings: "The Honourable Member (George Lansbury) said something about the Government and he has talked about rumours. If the Honourable Member has any charge to make against the Government as a whole or against individual Members of it, I think it ought to be stated openly. The reason why the government wanted a frank discussion before going to Committee was because we wanted to bring here these rumours, these sinister rumours that have been passed from one foul lip to another behind the backs of the House." (108)

Later that day, Rufus Isaacs issued a statement about his share-dealings. "Never from the beginning... have I had one single transaction with the shares of that company. I am not only speaking for myself but also speaking on behalf, I know, of both my Right Honourable Friends the Postmaster General and the Chancellor of the Exchequer who, in some way or another, in some of the articles, have been brought into this matter". (109)

Leopold Maxse, the editor of The National Review, pointed out that Isaacs had been careful in his use of words. He speculated why he said that he had not purchased shares in "that company" rather than the "Marconi company". Maxse pointed out: "One might have conceived that (the Ministers) might have appeared at the first sitting clamouring to state in the most categorical and emphatic manner that neither directly nor indirectly, in their names or other people's names, have they had any transactions whatsoever... In any Marconi company throughout thc negotiations with the Government". (110)

Asquith announced that he would set-up a committee to look into the possibility of insider dealings. The committee had six Liberals (including the chairman, Albert Spicer), two Irish Nationalists and one Labour MP, which provided a majority over six Conservatives. The committee took evidence from witnesses for the next six months and caused the Government a great deal of embarrassment. (111)

On 14th February, 1913, the French newspaper, Le Matin, reported that Herbert Samuel, David Lloyd George and Rufus Isaacs, had purchased Marconi shares at £2 and sold them when they reached the value of £8. When it was pointed out that this was not true, the newspaper published a retraction and an apology. However, on the advice of Winston Churchill, they decided to take legal action against the newspaper.

Churchill argued that this would provide an opportunity to shape the consciousness of the general public. He suggested that the men should employ two barristers, Frederick Smith and Edward Carson, who were members of the Conservative Party: "The public was bound to notice that the integrity of two Liberal ministers was being defended by normally partisan members of the Conservative Party, and their appearance on behalf of Isaacs and Samuel would make it impossible for them to attack either man in the House of Commons debate which would surely follow." (112)

Churchill also had a meeting with Alfred Harmsworth, Lord Northcliffe, the owner of The Times and The Daily Mail and persuaded him to treat the accused men "gently" in his newspapers. (113) However, other newspapers were less kind and gave a great deal of coverage to the critics of the government. For example, The Spectator, reported a speech made by Robert Cecil, where he argued: "It was his duty to express his honest and impartial opinion on the conduct of Mr. Lloyd George in the Marconi transaction. He had never said or suggested that the transaction was corrupt; but he did say that, if it was to be approved and recognized as the common practice among Government officials, then one of our greatest safeguards against corruption was absolutely destroyed. The transaction was bad and grossly improper, and it was made far worse by the fact that Mr. Lloyd George went about posing as an injured innocent. For a man in his position to defend that transaction was even worse than entering into it." (114)

During the House of Commons investigation the three accused Liberal MPs admitted they had purchased shares in the Marconi Company of America. However, as David Lloyd George pointed out, he had held no shares in any company which did business with the government and that he had never made improper use of official information. He ridiculed the charges which were made against him - some of which he invented, for example, the claim that he had made a profit of £60,000 on a speculative investment or that owned a villa in France. (115)

Alexander Murray was unable to appear before the Marconi Enquiry because he had resigned from the government and was working in Bogotá in Columbia. However, during the investigation, Murray's stockbroker was declared bankrupt and, in consequence, his account books and business papers were open to public examination. They revealed that Murray had not only purchased 2,500 shares in the American Marconi Company, but had invested £9,000 in the company on behalf of the Liberal Party. (116)

H. H. Asquith and Percy Illingworth, the new Chief Whip, denied knowledge of these shares. According to George Riddell, a close friend of both men, Asquith and Illingworth had known about this "for some time". (117) John Grigg, the author of Lloyd George, From Peace To War 1912-1916 (1985), has argued that Asquith was also aware of these shares and this explains why he was so keen to cover-up the story. "If he had shown any sign of abandoning them, they might have contemplating abandoning him, and vice versa... there was probably a mutual recognition of the need for solidarity in a situation where the abandonment of one might well have led to the ruin of all." (118)

On 30th June, 1913, the Select Committee provided three reports on the Marconi case. The majority (government) report claimed that no Minister had been influenced in the discharge of his public duties by any interest he might have had in any of the Marconi or other undertakings, or had utilized information coming to him from official sources for private investment or speculation.

The Minority (opposition) report criticised the whole handling of the share issue and found "grave impropriety" in the conduct of David Lloyd George, Rufus Isaacs and Alexander Murray, both in acquiring the shares at the advantageous price and in subsequent dealings in them. It also censored them for their lack of candour, especially Murray, who had refused to return to England to testify.

Although the chairman on the enquiry, Albert Spicer, signed the majority report, he also published his own report where he heavily criticised Rufus Isaacs for not disclosing at the beginning that he had bought shares in the Marconi Company. Spicer claimed that it was this lack of candour that resulted in the large number of rumours about the corrupt actions of the government ministers. (119)

In October, 1913, Rufus Isaacs, was appointed Lord Chief Justice of England. Newspapers complained that it appeared that he had been promoted as a reward for not disclosing the full truth about his share-dealings. However, it was reported by Lord Northcliffe that only five people had sent letters to his newspapers on the subject and "the whole Marconi business looms much larger in Downing Street than among the mass of the people". (120)

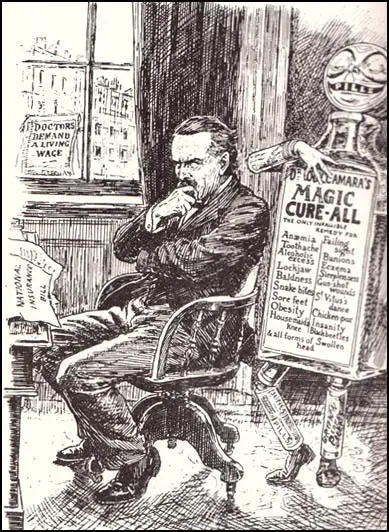

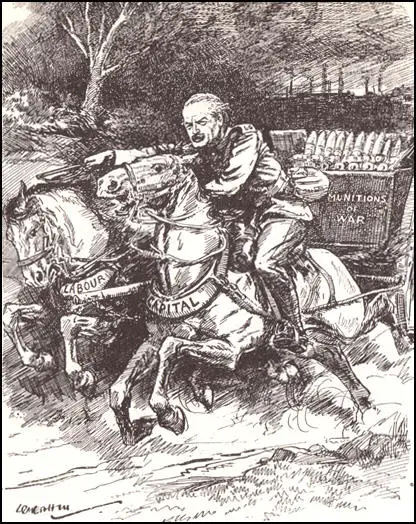

Leonard Raven-Hill, Blameless Telegraphy (25th June, 1913)

C. K. Chesterton, one of the men who exposed the scandal, agreed: "The object of the Eye-Witness was to make the English public know and care about the perils of political corruption. It is now certain that the public does know. It is not so certain that the public does care." However, he did go on to argue that it did have a long-term impact on the British public: "It is the fashion to divide recent history into Pre-War and Post-War conditions. I believe it is almost as essential to divide them into Pre-Marconi and Post-Marconi days. It was during the agitations upon that affair that the ordinary English citizen lost his invincible ignorance; or, in ordinary language, his innocence". (121)

In a speech at the National Liberal Club, David Lloyd George, attempted to defend the politicians involved in the Marconi case: "I should like to say one word about politicians generally. I think that they are a much-maligned race. Those who think that politicians are moved by sordid, pecuniary considerations know nothing ofeither politics or politicians. These are not the things that move us...The men who go into politics to make money are not politicians... We all have ambitions. I am not ashamed to say so. I speak as one who boasts: I have an ambition. I should like to be remembered amongst those who, in their day and generation, had at least done something to lift the poor out of the mire."

Lloyd George went on to argue that it was politicians like him who were protecting the public from other powerful forces: "The real peril in politics is not that individual politicians ofhigh rank will attempt to make a packet for themselves. Read the history of England for the past fifty years. The real peril is that powerful interests will dominate the Legislature, will dominate the Executive, in order to carry through proposals which will prey upon the community. That is where tariffs - the landlord endowment - will come in." (122)

Outbreak of the First World War

Alfred Harmsworth, Lord Northcliffe, used his newspapers to urge an increase in defence spending and a reduction in the amount of money being spent on social insurance schemes. In one letter to Lloyd George he suggested that the Liberal government was Pro-German. Lloyd George replied: "The only real pro-German whom I know of on the Liberal side of politics is Rosebery, and I sometimes wonder whether he is even a Liberal at all! Haldane, of course, from education and intellectual bent, is in sympathy with German ideas, but there is really nothing else on which to base a suspicion that we are inclined to a pro-German policy at the expense of the entente with France." (123)

Lloyd George complained bitterly to H. H. Asquith about the demands being made by Reginald McKenna, First Lord of the Admiralty, to spend more money on the navy. He reminded Asquith of "the emphatic pledges given by us before and during the general election campaign to reduce the gigantic expediture on armaments built up by our predecessors... but if Tory extravagance on armaments is seen to be exceeded, Liberals... will hardly think it worth their while to make any effort to keep in office a Liberal ministry... the Admiralty's proposals were a poor compromise between two scares - fear of the German navy abroad and fear of the Radical majority at home... You alone can save us from the prospect of squalid and sterile destruction." (124)

Lloyd George was constantly in conflict with McKenna and suggested that his friend, Winston Churchill, should become First Lord of the Admiralty. Asquith took this advice and Churchill was appointed to the post on 24th October, 1911. McKenna, with the greatest reluctance, replaced him at the Home Office. This move backfired on Lloyd George as the Admiralty cured Churchill's passion for "economy". The "new ruler of the King's navy demanded an expenditure on new battleships which made McKenna's claims seem modest". (125)

The Admiralty reported to the British government that by 1912 Germany would have 17 dreadnoughts, three-fourths the number planned by Britain for that date. At a cabinet meeting David Lloyd George and Winston Churchill both expressed doubts about the veracity of the Admiralty intelligence. Churchill even accused Admiral John Fisher, who had provided this information, of applying pressure on naval attachés in Europe to provide any sort of data he needed. (126)

Admiral Fisher refused to be beaten and contacted King Edward VII about his fears. He in turn discussed the issue with H. H. Asquith. Lloyd George wrote to Churchill explaining how Asquith had now given approval to Fisher's proposals: "I feared all along this would happen. Fisher is a very clever person and when he found his programme in danger he wired Davidson (assistant private secretary to the King) for something more panicky - and of course he got it." (127)

The assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand did not immediately cause a reaction in Britain. David Lloyd George admitted that he heard the news he suspected that it would result in a war in the Balkans but did not believe such a conflict would involve Britain. He also pointed out that the Cabinet, although it was meeting twice a day, because of the crisis in Ireland, they did not even discuss the issue of Serbia and the assassination for another three weeks. (128)

Lloyd George told C. P. Scott that there is "no question of our taking part in any war in the first instance... and knew of no minister who would be in favour of it". In a letter a few days later to King George V he described the impending conflict as "the greatest event for many years past" but he added "happily there seems no reason why we should be anything other than a spectator". H. H. Asquith, instructed Sir Edward Grey, the Foreign Secretary, to "inform the French and German ambassadors that, at this stage, we were unable to pledge ourselves in advance either under all conditions to stand aside or in any conditions to join in." (129)

On 23rd July, 1914, George Buchanan, the British ambassador to Russia, wrote to Sir Edward Grey, about the discussions he had following the assassination: "As they both continued to press me to declare our complete solidarity with them, I said that I thought you might be prepared to represent strongly at Vienna and Berlin danger to European peace of an Austrian attack on Serbia. You might perhaps point out that it would in all probability force Russia to intervene, that this would bring Germany and France into the field, and that if war became general, it would be difficult for England to remain neutral. Minister for Foreign Affairs said that he hoped that we would in any case express strong reprobation of Austria's action. If war did break out, we would sooner or later be dragged into it, but if we did not make common cause with France and Russia from the outset we should have rendered war more likely." (130)

Grey replied to Buchanan on the 25th July: "I said to the German Ambassador that, as long as there was only a dispute between Austria and Serbia alone, I did not feel entitled to intervene; but that, directly it was a matter between Austria and Russia, it became a question of the peace of Europe, which concerned us all. I had furthermore spoken on the assumption that Russia would mobilize, whereas the assumption of the German Government had hitherto been, officially, that Serbia would receive no support; and what I had said must influence the German Government to take the matter seriously. In effect, I was asking that if Russia mobilized against Austria, the German Government, who had been supporting the Austrian demand on Serbia, should ask Austria to consider some modification of her demands, under the threat of Russian mobilization." (131)

Several members of the Black Hand group interrogated by the Austrian authorities claimed that three men from Serbia, Dragutin Dimitrijevic, Milan Ciganovic, and Major Voja Tankosic, had organised the plot to kill Archduke Ferdinand. On 25th July, 1914, the Austro-Hungarian government demanded that the Serbian government arrest the men and send them to face trial in Vienna. Nikola Pasic, the prime minister of Serbia, told the Austro-Hungarian government that he was unable to hand over these three men as it "would be a violation of Serbia's Constitution and criminal in law". Three days later Austro-Hungarian declared war on Serbia. (132)

Despite these events, Sir Edward Grey was still confident that war could be avoided and departed for a fishing holiday in Hampshire. On 26th July, 1914, Prince Henry of Prussia, had another meeting with King George V. Later that day he wrote a letter to his brother of Kaiser Wilhelm II, that George had told him: "We shall try all we can to keep out of this, and shall remain neutral." Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz, the Commander of the German Navy, doubted the value of such a remark, however, the Kaiser replied: "I have the word of the a King, and that is enough for me." (133)