Charles Trevelyan

Charles Trevelyan, the son of George Otto Trevelyan, the Liberal MP, was born in Park Lane, London, on 28th October 1870.

His mother, Caroline Philips, was the daughter of Robert Needham Philips, who was also a member of the House of Commons. Over the next few years he served under William Ewart Gladstone in several cabinet posts. (1)

Charles' brother, George Macaulay Trevelyan, later claimed that their childhood was very political. He described how "a sense of drama of English and Irish history was purveyed to me through daily sights and experiences, with my father as commentator and bard." (2)

His father was very wealthy and the family lived in three different houses. This included a large house in London, Welcombe House, a red-brick mansion in Straford-upon-Avon, and Wallington Hall in Morpeth. In 1880 he was sent to a preparatory school at Hoddesdon called The Grange. (3)

Charles was educated at Harrow and Trinity College where he became friends with Bertrand Russell. (4) He graduated from Cambridge University in 1892 with a second-class history degree. He was upset he did not get a first: "Things are past the point of redemption. Oh it is so horrible. All my courage is gone, all my strong self confidence, all my hope. The very brightness of my prospects as the world would say, is a curse on me! What can it lead to but the repetition of the same miserable story of inadequacy and inefficiency in the end?" (5)

Charles Trevelyan: House of Commons

Charles Trevelyan helped John Morley in his successful campaign to become MP for Newcastle. Morley arranged for him to become Lord Houghton's private secretary. Houghton was Lord Lieutenant of Ireland and the job involved Trevelyan working in Dublin. (6)

He was a supporter of Home Rule and disliked the way the administration spoke about the Irish people: "One of the men spoke of politics and Home Rule bitterly, in that high-handed, disdainful, superior way that only Tories can speak, spurning their hearer's opinions, getting the ruder and more blatant if they see he objects. He spoke of the Irish as ruffians, and used the worst sort of language towards them." (7)

In 1895 Charles Trevelyan joined the Fabian Society and developed a close relationship with Sidney Webb, Beatrice Webb, George Bernard Shaw, Bertrand Russell, H. G. Wells, Herbert Samuel and Graham Wallas. (8) During this period he developed socialistic views on social reform. He was especially impressed by the views of one of his new friends: "Shaw gives the best exposition of the state of things one could hope to hear." (9)

Members disagreed about Trevelyan's abilities. Beatrice Webb described him as "a man who had every endowment - social position, wealth, intelligence, an independent outlook, good looks, good manners". H. G. Wells was less impressed and argued that "undoubtedly high-minded, Trevelyan had little sense of humour or irony, and was only marginally less self-satisfied and unendurably boring than his youngest brother, George." Bertrand Russell thought he was less gifted than his two brothers. (10)

Charles Trevelyan was adopted as the Liberal Party parliamentary candidate for North Lambeth, but was narrowly defeated in the 1895 General Election. The following year he argued that he was attracted to the philosophy of socialism. "I have the greatest sympathy with the growth of the socialist party. I think they understand the evils that surround us and hammer them into people's minds better than we Liberals. I want to see the Liberal party throw its heart and soul fearlessly into reform so as to prevent a reaction from the present state of thugs and the violent revolution that would inevitably follow it." (11)

Trevelyan took a strong interest in education and in 1896 he was elected to the London School Board. Family influence enabled him to being adopted for the constituency of Elland, and entered parliament after a by-election in March 1899. Charles Trevelyan was a very independent member of the House of Commons and took his brother's advice: "It is a rule that no Trevelyan ever sucks up either to the press, or the chiefs, or the 'right people'. The world has given us money enough to enable us to do what we think is right. We thank it for that and ask no more of it, but to be allowed to serve it." (12)

Trevelyan met and fell in love with Mary Katharine Bell, the daughter of Sir Hugh Bell, a wealthy businessman. In a letter he sent on 20th December, 1903, he outlined his his career prospects. "I am constantly anxious that in your newness to affairs you should not make pretty dreams for yourself of great success for me... I have not the quickness, variety or imagination of outlook which can possibly enable me ever to deal with the complicated revolutions of our national politics. I can only do my duty. And so little do I think there is any good chance of rising to any high position with my mediocre store of knowledge and ability, that I shall try less and less to try for position and more and more to take a line I think right." (13) They married on 6th January 1904. Over the next few years they had three sons and four daughters. (14)

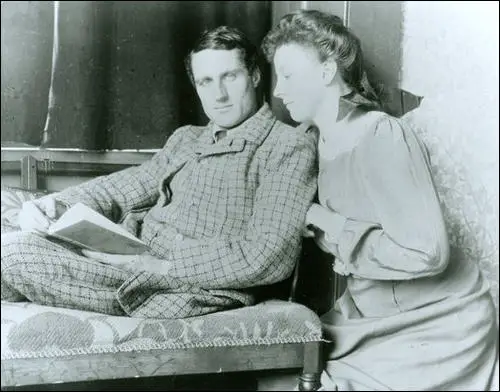

Photograph of Charles Trevelyan and Mary Katharine Bell in September 1903

Following the 1906 General Election, Trevelyan was disappointed not to be offered a post in the Liberal Government headed by Henry Campbell-Bannerman. It was generally believed that the reason for this was Trevelyan's left-wing political views. (15) His cousin, Morgan Philips Price, commented that "his sincerity often led him to be intolerant of other people's opinions, and with a greater degree of tact he could have accomplished much more of what he wanted." (16)

In the House of Commons Trevelyan advocated taxation of land values, Liberal–Labour co-operation on social legislation, and the ending of the House of Lords. As his biographer pointed out: "Trevelyan's comments upon his party's elders and leaders were often tactless, while his attacks upon policies he considered mistaken were intemperate. Not a trimmer by nature, his demeanour frequently suggested impatience and insensitivity." (17)

In October 1908, the new Prime Minister, Herbert Asquith, appointed Trevelyan to the junior post of parliamentary under-secretary at the Board of Education. In this post he argued passionately for the establishment of a completely secular system of national education. This made him unpopular with MPs who held strong religious beliefs.

In the 1910 General Election Trevelyan suggested that it was important to reform Parliament: "I wish to make it clear from the onset that at the coming election I want support on no other understanding that the new Parliament is to destroy once and for ever, the power of the hereditary chamber to reverse the decisions of the representatives of the people. The power to delay or reject supplies must be abolished, and they must never again enjoy an absolute veto over ordinary legislation. They have rendered fruitless the most serious work of the present House of Commons." (18)

First World War

At the end of July, 1914, it became clear to the British government that the country was on the verge of war with Germany. Four senior members of the government, Charles Trevelyan, David Lloyd George, John Burns and John Morley, were opposed to the country becoming involved in a European war. They informed the Prime Minister, Herbert Asquith, that they intended to resign over the issue. When war was declared on 4th August, three of the men, Trevelyan, Burns and Morley, resigned, but Asquith managed to persuade Lloyd George, his Chancellor of the Exchequer, to change his mind.

The anti-war newspaper, The Daily News, commented: "Among the many reports which are current as to Ministerial resignations there seems to be little doubt in regard to three. They are those of Lord Morley, Mr. John Burns, and Mr. Charles Trevelyan. There will be widespread sympathy with the action they have taken. Whether men approve of that action or not it is a pleasant thing in this dark moment to have this witness to the sense of honour and to the loyalty to conscience which it indicates... Mr. Trevelyan will find abundant work in keeping vital those ideals which are at the root of liberty and which are never so much in danger as in times of war and social disruption." (19)

In a letter to his constituents Trevelyan explained his reasons for resignation: "However overwhelming the victory of our navy, our commerce will suffer terribly. In war too, the first productive energies of the whole people have to be devoted to armaments. Cannon are a poor industrial exchange for cotton. We shall suffer a steady impoverishment as the character of our work exchanges. All this I felt so strongly that I cannot count the cause adequate which is to lead to this misery. So I have resigned." (20)

However, Trevelyan's actions were extremely unpopular with most people. A. J. A. Morris has argued that it was clear to Trevelyan that "Britain was condemned to war for no better reason than sentimental attachment to France and hatred of Germany. Trevelyan resigned from the government in protest. By this action he found himself estranged from most of his family, condemned and vilified by a hysterical press, and rejected by his constituency association." (21)

George Lansbury, a senior figure in the Labour Party praised the actions of Charles Trevelyan and predicted it marked the end of his political career: "He must have known when he resigned that he was giving the death blow to his career, and the courage which compels such a step is not to be distinguished from the courage of a soldier who falls in battle". (22)

The journalist, Morgan Philips Price, went to see Charles Trevelyan and suggested that they formed an organisation against the First World War. Trevelyan now made contact with two pacifist members of the Liberal Party, Norman Angell and E. D. Morel, and Ramsay MacDonald, the leader of the Labour Party. They also had discussions with Bertrand Russell and Arthur Ponsonby, who had also spoken out against the war. (23)

A meeting was held and after considering names such as the Peoples' Emancipation Committee and the Peoples' Freedom League, they selected the Union of Democratic Control. Other members included J. A. Hobson, Charles Buxton, Ottoline Morrell, Philip Morrell, Frederick Pethick-Lawrence, Arnold Rowntree, George Cadbury, Helena Swanwick, Fred Jowett, Tom Johnston, Philip Snowden, Ethel Snowden, David Kirkwood, William Anderson, Mary Sheepshanks, Isabella Ford, H. H. Brailsford, Eileen Power, Israel Zangwill, Margaret Llewelyn Davies, Konni Zilliacus, Margaret Sackville, Hastings Lees-Smith and Olive Schreiner.

Members of the UDC agreed that one of the main reasons for the conflict was the secret diplomacy of people like Britain's foreign secretary, Sir Edward Grey. They decided that the Union of Democratic Control should have three main objectives: (i) that in future to prevent secret diplomacy there should be parliamentary control over foreign policy; (ii) there should be negotiations after the war with other democratic European countries in an attempt to form an organisation to help prevent future conflicts; (iii) that at the end of the war the peace terms should neither humiliate the defeated nation nor artificially rearrange frontiers as this might provide a cause for future wars. (24)

Over the next couple of years the UDC became the leading anti-war organisation in Britain. Trevelyan wrote articles for newspapers and gave a series of lectures on the need to negotiate a peace with Germany. As a result of this Trevelyan was condemned in the popular press as being a "pro-German, unpatriotic, scoundrel". He was also criticised for his stance on the war by his father, George Otto Trevelyan. (25) However, Trevelyan continued to campaign for a peace settlement with Germany. (26)

The Daily Sketch launched a personal attack on Trevelyan accusing him of being pro-German: "Trevelyan would then have a very congenial atmosphere - in the Reichstag. We have no time to listen to his foolish and pernicious talk. It is a scandal that he should be in Parliament when he continues to preach these pro-German and utterly impracticable pacifist doctrines. Trevelyan must go". (27)

Charles was especially upset by the criticism of his older brother, George Macaulay Trevelyan. "I know that wisdom may begin to come to poor human beings through misery. But even I doubt when I see people like George carried away by shallow fears and ill-informed hatreds... It shows how absurdly far we are from brotherly feeling to foreigners when even in him it is a shallow veneer. He like all the rest wants to hate the Germans... I am more discouraged by it than anything else because it shows the helplessness of intellect before national passion." (28)

The Daily Express listed details of future UDC meetings and encouraged its readers to go and break-up them up. Although the UDC complained to the Home Secretary about what it called "an incitement to violence" by the newspaper, he refused to take any action. Over the next few months the police refuse to protect UDC speakers and they were often attacked by angry crowds. After one particularly violent event on 29th November, 1915, the newspaper proudly reported the "utter rout of the pro-Germans". (29)

The government saw Union of Democratic Control as an extremely dangerous organisation. Basil Thompson, head of the Criminal Investigation Division of Scotland Yard, and future head of Special Branch, was asked to investigate the UDC. Thompson reported that the UDC "is not a revolutionary body, and it has been appealing, at any rate in the early days of the war, more to the intellectual classes than to the working class". He went on to argue that its funds came from the Society of Friends and "Messrs. Cadbury, Fry and Rowntree". (30)

George Bernard Shaw urged Trevelyan to become the leader of the progressive forces in the House of Commons: "You have great advantages: you have an unassailable social and financial position, intellectual integrity and historical consciousness, character, personality, good looks, style, conviction, everything they lack except cinema sentiment and vulgarity. If you feel equal to a deliberate assumption of responsibility it is clear to me that you... can very soon become the visible alternative nucleus to the George gang and the Asquith ruin." (31)

On 2nd February 1918 Trevelyan published in the radical weekly The Nation the assertion that the Labour Party, and not the Liberal Party, was now best fitted to root out the evils of social and economic privilege. "Our lives have been spoilt by compromise, because we tolerated armament firms and secret diplomacy and the rule of wealth. The world war has revealed the real meaning of our social system. As imperialism, militarism and irresponsible wealth are everywhere trying to crush democracy today, so democracy must treat these forces without mercy. The root of all evil is economic privilege... Where shall we find the political combination which will offer us resource in its strategy, coherence in its policy, and fearlessness in its proposals?" (32)

Charles Trevelyan's parents were upset when he told them he was going to join the Labour Party. His mother wrote: "Your decision to join the Labour party is, of course, a trouble to us. I hope you will get on with your new friends and not let them lead you into deep waters. It will make a considerable difference to you and your family but you have doubtless considered everything. I had hoped that after the war we might find ourselves all more in sympathy on public affairs." (33)

Charles replied that the Labour Party in the future would become the main force of progressive change: "I think from your letter you are looking from the wrong angle at my action in joining the Labour party. I of course knew that you would regret my leaving the Liberal party, but there is nothing unnatural, sudden or surprising about it. You talk of 'my new friends'. In the first place I have worked in close comradeship with several of the leaders of the Labour party for four years. There is nothing to choose in personality, ability, or character between them and the pick of the Liberal Cabinet, with whom I previously associated in politics. But beyond that at least half my Liberal friends are either joining the Labour party now or are on the verge of joining it... Any amount of my private friends of the same education, and, if that matters, social position, are joining now. I don't want to make you realise this in order to make you uncomfortable about the Liberal party, but in order that you may be comfortable about me." (34)

In the 1918 General Election all the leading members of the Union of Democratic Control lost their seats in Parliament. This included Charles Trevelyan, who suffered a crushing defeat at Elland. On the surface it seemed that the UDC had achieved very little. However, as A.J.P. Taylor has pointed out: "It launched a version of international relations which gradually won general acceptance far beyond the circle of those who knew they were being influenced by the UDC." (35)

1924 Labour Government

Charles Trevelyan was a strong critic of the Versailles Treaty. In his book, From Liberalism to Labour (1921), he argued: "Historians and philosophers, like catch-penny Daily Mail scrawlers, proclaimed the sole guilt of Germany, or raved at the brutalities in Belgium as proof of superhuman devilry in the Germans. But when offences against humanity were committed by the Allied Governments, they showed the same want of courage or the same narrowness of vision as the German professors whom they were always denouncing. What collective protest of Liberal intellectuals was there against the slaughter of the children at Karlsruhe, against the looting of Hungary, or against the supreme atrocity of the starvation of Central Europe?" (36)

In the 1922 General Election Trevelyan was elected to represent the Labour Party at Newcastle Upon Tyne Central. When Ramsay MacDonald became Prime Minister in January 1924 he appointed Trevelyan as his President of the Board of Education. He told his wife that "I no longer have six children - I have six million." (37)

In the short-lived Labour Government Trevelyan argued for a reduction in educational inequalities. "During his term of office, approval was given to forty new secondary schools; a survey was instituted in order to provide for the replacement of as many as possible of the more insanitary or obsolete elementary schools; the proportion of free places in secondary schools was increased; state scholarships, which had been in suspense, were restored, and maintenance allowances for young people in secondary schools were increased; the adult education grant was tripled; and local authorities were empowered, where they wished, to raise the school-leaving age to fifteen." (38)

According to his biographer, Trevelyan was "a sound administrator, he was not overawed, as were many of his colleagues, by his civil servants... his performances at the dispatch box won back his father's approval." (39) Trevelyan's main objective was to provide "the children of of the workers to have the same opportunities as those of the wealthy". He proposed to do so by expanding secondary education and raising the school-leaving age. He reversed the cuts in education spending imposed in 1922, increased the number of free places at grammar schools, and encouraged (but could not require) local authorities to raise the school leaving age to fifteen. He also declared that there would be a break between primary and secondary education at the age of 11. (40)

H. G. Wells wrote to Trevelyan: "I think your work for education has been of outstanding value and that everyone who hopes for a happier, more civilised England should vote for all, irrespective of party association. I have watched your proceedings with close interest and I am convinced that there has never been a better, more far sighted, harder working, and more unselfishly devoted Minister of Education than yourself." (41)

On 8th October, 1924, MacDonald lost a motion of no confidence in the House of Commons over the way he had dealt with the John Ross Campbell case. Just before the 1924 General Election, someone leaked news of the Zinoviev Letter to the Times and the Daily Mail. The letter was published in these newspapers and contributed to the defeat of MacDonald. The Conservatives won 412 seats and formed the next government. With his 151 Labour MPs, MacDonald became leader of the opposition in the House of Commons. (42)

Trevelyan now became the opposition spokesman on education. He also began to develop plans for a educational policy that could be implemented by the next Labour government. Trevelyan's plans included raising the school-leaving age to fifteen and increased public expenditure on education. Trevelyan also wanted a reduction in church control over education. He suggested that the government should provide finance to Anglican and Catholic schools in return for local managers giving control over their teachers to the local authorities.

Charles Trevelyan and Ramsay MacDonald

Following the 1929 General Election he was once again appointed as President of the Board of Education. However, Trevelyan's Education Bill, that included the measure of raising the school-leaving age to fifteen, ran into difficulties with Roman Catholic MPs on the Labour backbenches. Catholic bishops persuaded their MPs to insist on increased funding for Church schools. Trevelyan, "an atheist wary of the power of Church schools, was prepared to go some way towards meeting these concerns, but did not want to entrench the power of the Catholic lobby". (43)

Trevelyan wrote a letter to his old friend, Bertrand Russell, about the problem he faced: "I represent a constituency swarming with Irish Catholics. I would rather lose my seat than give the priesthood a bigger power in the schools. I am absolutely determined that the Labour Party shall not get into the hands of any religion, least of all Catholic.... Scotland has dealt with the question as well and tolerably as it probably can be. The schools are wholly in the hands of the people and teachers are appointed by the local authority. The task is tougher in England with the old Church of England on our back and the 6,000 single school areas." (44)

Jennie Lee was one of those MPs who came under considerable pressure from the Catholic lobby group over this bill. Even left-wing MPs such as James Maxton urged her to vote against the legislation. He told her that in "the West of Scotland I could challenge the authority of the Labour Party and still survive, but if I also antagonised the Catholic vote, there was not the slightest hope I could hold my seat." (45)

Trevelyan agreed to give extra money to schools but only if they agreed to come under the control of the local authorities. The bill raised the school-leaving age by one year and gave grants to the parents of children in their last year of school. (46) The bill was undermined in January 1931 by an amendment carried by John Scurr on behalf of Roman Catholic schools, which sought grants to accommodate increased pupil numbers, and was defeated in the House of Lords, largely because of the unfavourable financial climate, in February 1931. (47)

Trevelyan blamed Ramsay MacDonald for the failure to get his Education Bill through Parliament. He wrote to his wife that the prime minister undermined his attempts at educational reform: "MacDonald detests me because I am always quite definite and won't shirk things in the approved style. He will let me down if he possibly can, the real wrecker (is not the House of Lords) it is MacDonald with his timidity." (48)

Charles Trevelyan

On 19th February, 1931, Trevelyan resigned from the government. In a letter to the prime minister he explained his actions: "For some time I have realised that I am very much out of sympathy with the general method of Government policy. In the present disastrous condition of trade it seems to me that the crisis requires big Socialist measures. We ought to be demonstrating to the country the alternatives to economy and protection. Our value as a Government today should be to make people realise that Socialism is that alternative." (49)

Trevelyan told a meeting of the Parliamentary Labour Party that the main reason he had resigned: "I have for some time been painfully aware that I am utterly dissatisfied with the main strategy of the leaders of the party. But I thought it my duty to hold on as long as I had a definite job in trying to pass the Education Bill. I never expected a complete breakthrough to Socialism in this Parliament. But I did expect it to prepare the way by a Government which in spirit and vigour made such a contrast with the Tories and Liberals that we should be sure of conclusive victory next time."

He attacked the government for refusing to introduce socialist measures to deal with the economic crisis. He was also a supporter of the economist John Maynard Keynes: "Now we are plunged into an exampled trade depression and suffering the appalling record of unemployment. It is a crisis almost as terrible as war. The people are in just the mood to accept a new and bold attempt to deal with radical evils. But all we have got is a declaration of economy from the Chancellor of the Exchequer. We apparently have opted, almost without discussion, the policy of economy. It implies a faith, a faith that reduction of expenditure is the way to salvation. No comrades. It is not good enough for a Socialist party to meet this crisis with economy. The very root of our faith is the prosperity comes from the high spending power of the people, and that public expenditure on the social services is always remunerative." (50)

On 24th August 1931, MacDonald formed a National Government. Only three members of the Labour administration, Philip Snowden, Jimmy Thomas and John Sankey agreed to join the government. Other appointments included Stanley Baldwin (Lord President of the Council), Neville Chamberlain (Health), Samuel Hoare (Secretary of State for India), Herbert Samuel (Home Office), Philip Cunliffe-Lister (Board of Trade) and Lord Reading (Foreign Office).

On 8th September 1931, the National Government's programme of £70 million economy programme was debated in the House of Commons. This included a £13 million cut in unemployment benefit. Tom Johnson, who wound up the debate for the Labour Party, declared that these policies were "not of a National Government but of a Wall Street Government". In the end the Government won by 309 votes to 249, but only 12 Labour M.P.s voted for the measures. (51)

The cuts in public expenditure did not satisfy the markets. The withdrawals of gold and foreign exchange continued. On September 16th, the Bank of England lost £5 million; on the 17th, £10 million; and on the 18th, nearly £18 million. On the 20th September, the Cabinet agreed to leave the Gold Standard, something that John Maynard Keynes had advised the government to do on 5th August.

On 26th September, the Labour Party National Executive decided to expel all members of the National Government including Ramsay MacDonald, Philip Snowden, Jimmy Thomas and John Sankey. As David Marquand has pointed out: "In the circumstances, its decision was understandable, perhaps inevitable. The Labour movement had been built on the trade-union ethic of loyalty to majority decisions. MacDonald had defied that ethic; to many Labour activists, he was now a kind of political blackleg, who deserved to be treated accordingly." (52)

The 1931 General Election was held on 27th October, 1931. MacDonald led an anti-Labour alliance made up of Conservatives and National Liberals. It was a disaster for the Labour Party with only 46 members winning their seats. Several leading Labour figures, including Charles Trevelyan, Arthur Henderson, John R. Clynes, Arthur Greenwood, Jennie Lee, Herbert Morrison, Emanuel Shinwell, Frederick Pethick-Lawrence, Hugh Dalton, Susan Lawrence, William Wedgwood Benn, and Margaret Bondfield lost their seats.

The Socialist League

Following the election G.D.H. Cole created the Society for Socialist Inquiry and Propaganda (SSIP). This was later renamed the Socialist League. Charles Trevelyan joined the organization. Other members included William Mellor, Stafford Cripps, H. N. Brailsford, D. N. Pritt, R. H. Tawney, Frank Wise, David Kirkwood, Clement Attlee, Neil Maclean, Frederick Pethick-Lawrence, Alfred Salter, Jennie Lee, Gilbert Mitchison, Harold Laski, Frank Horrabin, Ellen Wilkinson, Aneurin Bevan, Ernest Bevin, Arthur Pugh, Michael Foot and Barbara Betts. J. T. Murphy became its secretary. Murphy saw the Socialist League as "the organization of revolutionary socialists who are an integral part of the Labour movement for the purpose of winning it completely for revolutionary socialism". (53)

In the 1932 Labour Conference the Socialist League defeated the platform with the proposal to go beyond nationalisation of the Bank of England to to take other banks into public ownership on the grounds that control of them would be essential for real socialist planning. Another successful Socialist League resolution laid down "that the leaders of the next Labour Government and the Parliamentary Labour Party be instructed by the National Conference that, on assuming office... definite Socialist legislation must be immediately promulgated... we must have Socialism in deed as well as in words". (54)

A. J. A. Morris, pointed out: "Trevelyan encouraged the Socialist League, gave help both political and material to a number of aspiring and established left-wingers, and seemed quite convinced that the Labour Party was at last committed to socialism. There was a brief moment of personal triumph at the annual party conference in 1933. He successfully introduced a resolution that, if there were even a threat of war, the Labour Party would call a general strike." (55)

George Bernard Shaw, Edith Bulmer and Charles Trevelyan (1936)

The United Front agreement won only narrow majority at a Socialist League delegate conference in January, 1937 - 56 in favour, 38 against, with 23 abstentions. The United Front campaign opened officially with a large meeting at the Free Trade Hall in Manchester on 24th January. Three days later the Executive of the Labour Party decided to disaffiliated the Socialist League. They also began considering expelling members of the League. G.D.H. Cole and George Lansbury responded by urging the party not to start a "heresy hunt".

Arthur Greenwood was one of those who argued that the rebel leader, Stafford Cripps, should be immediately expelled. Cripps was expelled by the National Executive Committee by eighteen to one. He was followed by Charles Trevelyan, Aneurin Bevan and George Strauss in February. On 24th March, 1937, the National Executive Committee declared that members of the Socialist League would be ineligible for Labour Party membership from 1st June. Over the next few weeks membership fell from 3,000 to 1,600. In May, G.D.H. Cole and other leading members decided to dissolve the Socialist League. (56)

Retirement

Trevelyan now decided to retire from politics. In 1937 he made a new will where he left Wallington Hall, not to his eldest son George, but to the National Trust. He explained his decision in a radio broadcast: "To most owners it would be a terrible wrench to consider alienating their family houses and estates. To me, it is natural and reasonable that a place such as this should come into public ownership, so that the right to use and enjoy it may be forever secured to the community. As a socialist, I am not hampered by any sentiment that the place I love will be held in perpetuity for the people of my country." (57)

He retained his socialist views to the end of his life and this made him plenty of enemies: "My well to do neighbours in the county and Newcastle are from their point of view right in detesting my attitude. I am very dangerous to their way of life because I know only too well what I am aiming at. It is a much more serious thing to the existing order when not only are pious opinions expressed that it is an unsocial thing for private people to own country houses and castles and thousands of acres, but when they are actually surrendered as a matter of principle. I am not troubled in their thinking me a traitor. Indeed I hate their loyalties. I am much more concerned that the masses understand what I am doing, and feel that the world is changing in the direction they never really hoped to see twenty years ago." (58)

Trevelyan carried on a long-term relationship with Edith Bulmer. In 1943, Edith, aged 39, gave birth to Martin Bulmer. Charles had fathered an illegitimate child at the age of 72. His wife was furious and she wrote to her friend about her feelings: "If he were an obscure person living in a small street, it would not matter. But he is a very prominent person, living in a great house and in the public eye. His good name will suffer... The curious thing about the whole story is that he is devoted to me. Of that I am absolutely certain. He has the greatest concern for my happiness, and is deeply distressed if I am not happy." (59)

According to Laura Trevelyan, "Charles was physically and intellectually vigorous to the last, commanding, interested and questioning what was going on in the world." (60) At the age of 79, Trevelyan wrote to Jennie Lee about his achievements in politics: "I have nothing to grumble about in regard to my life as a whole. I have done better than than I deserve by a long way." (61)

In another letter he recalled: "What made me any use in the world was having to stand nearly alone in the first war. Since then I have never found it hard to take my own line and have found out the way to do it. I discovered that if you believe a thing sufficiently strongly there is no need to fear isolation or unpopularity... If you see what you think is right clearly enough, there is really no difficulty. Most people's minds are rather mixed and foggy." (62)

Charles Trevelyan died aged 87 on 24th January 1958.

Primary Sources

(1) In 1895 Charles Trevelyan joined the Fabian Society. In a letter that he wrote to his parents, Trevelyan described a Fabian outing to Eastbourne (12th April, 1895)

We (Beatrice Webb, Sidney Webb, George Bernard Shaw, Herbert Samuel and Graham Wallas) travelled down together yesterday. At Eastbourne, a bus came to meet us with red wheels and a coachman in livery. Here we have monopolized the Hotel, except the bar, which is filled with tourists and fly men during the middle of the day. Till eleven and after five we have the whole of Beach Head to ourselves. It is glorious weather, and Mrs. Webb had had to borrow glycerin for her sunburn. I am teaching the whole party to bicycle. Mrs. Webb will soon be proficient. Mr. Webb is hopeless. Bernard Shaw is at the moment industriously tumbling about outside.

(2) Charles Trevelyan, letter to Caroline Trevelyan (12th April, 1895)

George Bernard Shaw is very much what I hoped and expected, excessively talkative, genial and amusing, and not unduly aggressive or cynical. He is not full of praise for anything or anybody - but is the perfection of real good nature.

(3) Charles Trevelyan, speech in Boston (1896)

I have the greatest sympathy with the growth of the socialist party. I think they understand the evils that surround us and hammer them into people's minds better than we Liberals. I want to see the Liberal party throw its heart and soul fearlessly into reform so as to prevent a reaction from the present state of things and the violent revolution that would inevitably follow it.

(4) Charles Trevelyan, speech (10th December, 1909)

I wish to make it clear from the onset that at the coming election I want support on no other understanding that the new Parliament is to destroy once and for ever, the power of the hereditary chamber to reverse the decisions of the representatives of the people. The power to delay or reject supplies must be abolished, and they must never again enjoy an absolute veto over ordinary legislation. They have rendered fruitless the most serious work of the present House of Commons.

(5) The Daily News (5th August, 1914)

Among the many reports which are current as to Ministerial resignations there seems to be little doubt in regard to three. They are those of Lord Morley, Mr. John Burns, and Mr. Charles Trevelyan. There will be widespread sympathy with the action they have taken.

Whether men approve of that action or not it is a pleasant thing in this dark moment to have this witness to the sense of honour and to the loyalty to conscience which it indicates... Mr. Trevelyan will find abundant work in keeping vital those ideals which are at the root of liberty and which are never so much in danger as in times of war and social disruption.

(6) Charles Trevelyan, letter to his constituents explaining why he had resigned on the decision of the Liberal Government to declare war on Germany (5th August 1914)

However overwhelming the victory of our navy, our commerce will suffer terribly. In war too, the first productive energies of the whole people have to be devoted to armaments. Cannon are a poor industrial exchange for cotton. We shall suffer a steady impoverishment as the character of our work exchanges. All this I felt so strongly that I cannot count the cause adequate which is to lead to this misery. So I have resigned.

(7) C. P. Scott, editor of the Manchester Guardian, wrote a letter to Charles Trevelyan suggesting that he should not publish a pamphlet he had written that raised doubts about the reported atrocities being committed by the Germans in Belgium (5th September, 1914)

It would be expedient to hold back the pamphlet. The war is at present going badly against us and any day may bring more serious news. I suppose that as soon as the Germans have time to turn their attention to us we may expect to see their big guns mounted on the other side of the Channel and their Zeppelins flying over Dover and perhaps London. People will be wholly impatient of any sort of criticism of policy at such a time and I am afraid that premature action now might destroy any hope of usefulness for your organisation (Union of Democratic Control) later. I saw Angell and Ramsay MacDonald yesterday afternoon and found that they had come to the same conclusion.

(8) The Daily Sketch (4th March, 1915)

Trevelyan would then have a very congenial atmosphere - in the Reichstag. We have no time to listen to his foolish and pernicious talk. It is a scandal that he should be in Parliament when he continues to preach these pro-German and utterly impracticable pacifist doctrines. Trevelyan must go.

(9) In August 1914, George Lansbury commented on Trevelyan's decision to resign from the government.

He must have known when he resigned that he was giving the death blow to his career, and the courage which compels such a step is not to be distinguished from the courage of a soldier who falls in battle.

(10) In 1915 leading members of the Union of Democratic Control, Charles Trevelyan, E. D. Morel and Arthur Ponsonby considered the possibility of joining the Independent Labour Party. Trevelyan wrote about it to Morel on 9th July, 1915.

I am inclined that I can be more useful to the UDC by being identified with no political party. I am clear that it would be fatal to any progress with Liberals for anyone to take a definite step towards political change of allegiance who is in a prominent position among us. We cannot yet tell at all how the political situation will develop. There is no hurry.

(11) Charles Trevelyan, speech (October 1915)

The ruling classes today nourish the conviction that national hatreds and rivalries are inevitable. I turn for hope away from the great and learned and rich who have had the making of the war, to the common men and women whose only responsibility is that they left the war to others to settle. It is only by democracy beginning to think for itself by the putting into operation of the principles of human brotherhood that anything can be made out of the present deplorable embroilment but unutterable and permanent human disaster.

(12) George Bernard Shaw, letter to Charles Trevelyan (28th February, 1918)

You have great advantages: you have an unassailable social and financial position, intellectual integrity and historical consciousness, character, personality, good looks, style, conviction, everything they lack except cinema sentiment and vulgarity. If you feel equal to a deliberate assumption of responsibility it is clear to me that you... can very soon become the visible alternative nucleus to the George gang and the Asquith ruin... I have been lately saying on occasion, "What about Trevelyan" and the only objection is that you seem to have specialised too much as a Pacifist.

(13) Charles Trevelyan, The Nation (2nd February, 1918)

Our lives have been spoilt by compromise, because we tolerated armament firms and secret diplomacy and the rule of wealth. The world war has revealed the real meaning of our social system. As imperialism, militarism and irresponsible wealth are everywhere trying to crush democracy today, so democracy must treat these forces without mercy. The root of all evil is economic privilege... Where shall we find the political combination which will offer us resource in its strategy, coherence in its policy, and fearlessness in its proposals?

(14) In a letter to his parents, Charles Trevelyan explained why he had joined the Labour Party (30th November 1918)

I have worked in close comradeship with several of the leaders of the Labour Party for four years. But beyond that at least half of my Liberal friends are either joining the Labour Party now or are on the verge of joining it. At least thirty Liberal members have been discussing the pros and cons of it for the last eighteen months. Any amount of my private friends of the same education, and, if that matters, social position as myself, are joining now.

(14) Letter to Charles Trevelyan from J. Pollack McCale, an old friend from Harrow School (3rd February, 1918)

Do you in the utter tosh you write at a time critical for our country, wish to turn Europe into a commune with Lenin as Prime Minister and Ramsay MacDonald as deputy? Do you wish to introduce us to the luxuries of Bolshevism, murder, rapine and pillage, or do you merely wish to see you own country ruined.

(15) Charles Trevelyan, From Liberalism to Labour (1921)

Historians and philosophers, like catch-penny Daily Mail scrawlers, proclaimed the sole guilt of Germany, or raved at the brutalities in Belgium as proof of superhuman devilry in the Germans. But when offences against humanity were committed by the Allied Governments, they showed the same want of courage or the same narrowness of vision as the German professors whom they were always denouncing. What collective protest of Liberal intellectuals was there against the slaughter of the children at Karlsruhe, against the looting of Hungary, or against the supreme atrocity of the starvation of Central Europe? The one clear note which they tried to strike early in the war was the right of all peoples to self-determination. They called for sympathy for Croats and Czecho-Slovaks and Italians under Austrian rule. They demanded the independence of Poland. But when Europe began to be repartitioned at Paris, and a dozen new oppressions were substituted for the old ones, there was no protest in the name of principle or justice or Liberalism against the fate of Germans annexed to Poland, Austrians to Italy and Czecho-Slovakia, Serbs and Hungarians to Roumania, Bulgarians to Serbia, and the other patent outrages to national feeling created by the new settlement. Liberalism did not even insist on the application of the full principle of nationalism on which it had staked everything in the war. It marched behind the triumphal car of the reactionaries and accepted the old interpretation of nationalism, which is justice for the victors. No great leading light for a torn and distracted world shone from learned and cultivated Liberal England.

This, then, is the first great factor in the present situation, that as a bulwark against the tide of reaction and militarism which has swept the governing classes of the victorious nations along, the Liberals are useless. Their Liberal "war to end war" has closed with an imperialist peace to perpetuate national injustice and armaments. And they have acquiesced.

(15) George Trevelyan wrote to his son when he heard he had been appointed Minister of Education (23rd January, 1924)

It is a great advantage indeed in any genuine and important office, to go to a department the working of which you familiarly know. To be the one man in a great office who knows nothing about the processes and the one man who has to make the decisions, is a most bewildering business. My father, even, felt it, and said that in his first fortnight at the Treasury he saw the snakes coming out of the papers in his dreams at night. Well, you have as long a family tradition of official work to keep up as George has of book-writing, and I have no doubt you will do it worthily.

(16) H. G. Wells, letter to Charles Trevelyan (21st October, 1924)

I think your work for education has been of outstanding value and that everyone who hopes for a happier, more civilised England should vote for all, irrespective of party association. I have watched your proceedings with close interest and I am convinced that there has never been a better, more far sighted, harder working, and more unselfishly devoted Minister of Education than yourself.

(17) Charles Trevelyan believed that the Zinoviev letter was responsible for Labour's defeat in the 1924 General Election. His friend, Francis Hirst, wrote about the matter to him on 3rd November 1924.

I will be utterly disgusted it the Labour Cabinet timidly resign with probing the mystery (of the Zinoviev letter) and explaining it to Parliament. It's the biggest electoral swindle. I personally believe you were right in denouncing it boldly as a forgery.

(18) Charles Trevelyan, letter to Bertrand Russell (May, 1929)

I represent a constituency swarming with Irish Catholics. I would rather lose my seat than give the priesthood a bigger power in the schools. I am absolutely determined that the Labour Party shall not get into the hands of any religion, least of all Catholic.

My anchor is the appointment of teachers. If I could get that into the hands of the public I would concede a great deal in other directions. Scotland has dealt with the question as well and tolerably as it probably can be. The schools are wholly in the hands of the people and teachers are appointed by the local authority. The task is tougher in England with the old Church of England on our back and the 6000 single school areas.

(19) Trevelyan believed Ramsay MacDonald did not give him enough support in his efforts to persuade the House of Lords to pass his 1930 Education Act. He wrote a letter to his wife about this issue on 16th November 1930.

MacDonald detests me because I am always quite definite and won't shirk things in the approved style. He will let me down if he possibly can, the real wrecker (is not the House of Lords) it is MacDonald with his timidity.

(20) Charles Trevelyan, letter of resignation to Ramsay MacDonald (19th February, 1931)

For some time I have realised that I am very much out of sympathy with the general method of Government policy. In the present disastrous condition of trade it seems to me that the crisis requires big Socialist measures. We ought to be demonstrating to the country the alternatives to economy and protection. Our value as a Government today should be to make people realise that Socialism is that alternative.

(21) Charles Trevelyan, speech to the Parliamentary Labour Party (19th February, 1931)

I have for some time been painfully aware that I am utterly dissatisfied with the main strategy of the leaders of the party. But I thought it my duty to hold on as long as I had a definite job in trying to pass the Education Bill. I never expected a complete breakthrough to Socialism in this Parliament. But I did expect it to prepare the way by a Government which in spirit and vigour made such a contrast with the Tories and Liberals that we should be sure of conclusive victory next time.

But the first session was a bitter disappointment. Now we are plunged into an exampled trade depression and suffering the appalling record of unemployment. It is a crisis almost as terrible as war. The people are in just the mood to accept a new and bold attempt to deal with radical evils. But all we have got is a declaration of economy from the Chancellor of the Exchequer. We apparently have opted, almost without discussion, the policy of economy. It implies a faith, a faith that reduction of expenditure is the way to salvation. No comrades. It is not good enough for a Socialist party to meet this crisis with economy. The very root of our faith is the prosperity comes from the high spending power of the people, and that public expenditure on the social services is always remunerative.

Though I differ profoundly with the present leadership I have not the slightest sympathy with the action of men like Mosley. The Labour Party is going to be the power of the future however long it takes to evolve leaders who know how to act. But it is as in an army. The leaders for the time must settle the strategy. The officers who command the battalions can retire, but they must not rebel. I have taken the one step of protest open to me. I resign my position as an officer and become a private soldier.

(22) Morgan Philips Price, My Three Revolutions (1969)

The May Economy Committee was appointed by the Government to recommend a general cutting down on all public expenditure. The Committee reported on these lines during the summer of 1931 and a general sacrifice of public works schemes was the result. In the holocaust my cousin Sir Charles Trevelyan's Education Bill was dropped. This Bill raised the school-leaving age by one year and gave grants to the parents of children in their last year at school. Owing to what happened to his Education Bill, Sir Charles resigned his office.

Student Activities

The Outbreak of the General Strike (Answer Commentary)

The 1926 General Strike and the Defeat of the Miners (Answer Commentary)

The Coal Industry: 1600-1925 (Answer Commentary)

Women in the Coalmines (Answer Commentary)

Child Labour in the Collieries (Answer Commentary)

Child Labour Simulation (Teacher Notes)

1832 Reform Act and the House of Lords (Answer Commentary)

The Chartists (Answer Commentary)

Women and the Chartist Movement (Answer Commentary)

Benjamin Disraeli and the 1867 Reform Act (Answer Commentary)

William Gladstone and the 1884 Reform Act (Answer Commentary)

Richard Arkwright and the Factory System (Answer Commentary)

Robert Owen and New Lanark (Answer Commentary)

James Watt and Steam Power (Answer Commentary)

Road Transport and the Industrial Revolution (Answer Commentary)

Canal Mania (Answer Commentary)

Early Development of the Railways (Answer Commentary)

The Domestic System (Answer Commentary)

The Luddites: 1775-1825 (Answer Commentary)

The Plight of the Handloom Weavers (Answer Commentary)

Health Problems in Industrial Towns (Answer Commentary)

Public Health Reform in the 19th century (Answer Commentary)

Classroom Activities by Subject