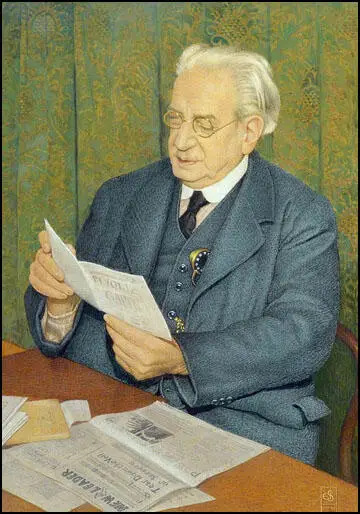

Frederick Jowett

Frederick William Jowett, the son of a textile worker, was born in Bradford on 31st January, 1864. One of eight children, he received little formal education and at the age of eight was working at the local textile mill.

On a Sunday his father, Nathaniel Jowett, would take his son out for long walks. A staunch radical, he took this opportunity to teach his son about politics.

His mother's family he was involved in the Chartist movement: "Occasionally she would reveal incidents of her early life in my hearing, and they sank deeply into my mind, although she was quite unaware of the fact. It seemed natural that she should tell me also of Chartist meetings, although she was so young at the time and so little that for safety against the crowd she crept under the wagon from which the speeches were delivered. Early impressions of this sort must surely have made me a potential democrat in my very early years."

Jowett became a power-loom overlooker at the age of nineteen and after attending evening classes in weaving and design at Bradford Technical College, was employed as a manager at the mill. On 19 July 1884 he married Emily Foster, the daughter of a Bradford wool waste dealer.

As a young man Jowett read the works of William Morris and John Ruskin and in 1886 he joined the Socialist League. This organisation ceased to exist after 1889 and so Jowett became involved with the Bradford Labour Union, a group formed to support strikers at the Manningham Mills in Bradford. Jowett was a Christian Socialist and was furious when local churchman criticised the strikers. Jowett responded by helping to form a Labour Church in the town.

According to J. A. Jowitt: "Out of that strike (at Manningham Mills) emerged a growing demand for independent working-class political activity, which, faced by locally a conservative Liberalism and a weak trade unionism, led to the formation in the spring of 1891 of the Bradford Labour Union". In 1892 Jowett became the first socialist to be elected to Bradford City Council. A few months later Jowett founded a branch of the Independent Labour Party in Bradford. As a member of the council Jowett instigated several important reforms that were eventually imitated by other authorities. as party Chairman.

In 1904 Bradford became the first local authority in Britain to provide free school meals. Jowett argued: "That it is the duty of the community to see that all children are sufficiently fed. That voluntary effort is not able to feed children who are regularly or temporarily in need of food. That when children attend school insufficiently fed, it shall be the duty of the education Committee, acting on information supplied by the teachers, to feed these children. It is not until the hunger-pangs are removed that people are able to think of something higher and to respond to the best impulses and appeals. Education on an empty stomach is a waste of money."

Another successful campaign was the clearing of a slum area and replacing it with new houses. Jowett was also a supporter of reforming the 1834 Poor Law. He was elected as a Poor Law Guardian and attempted to improve the quality of the food given to the children in the Bradford Workhouse.

Jonathan Priestley (father of J. B. Priestley), serving free school meals.

In the 1900 General Election Jowett was the Independent Labour Party candidate in West Bradford. His strong opposition to the Boer War probably cost him the election as he only lost by 41 votes. With the war over, Jowett comfortably won the seat in the 1906 General Election. In the House of Commons Jowett attempted to persuade the government to introduce legislation that he had pioneered in Bradford such as a school meals programme. While Jowett supported David Lloyd George in his attempts to introduce Old Age Pensions in 1908. However, he criticised the inadequate sums involved and the use of the Means Test. During this period Jowett established himself as one of the leading left-wing figures in Parliament and in 1909 was elected Chairman of the ILP.

Jowett was re-elected in the 1910 General Election. In the Socialist Review, a journal edited by John Bruce Glasier, Jowett suggested a new system of government. He argued that the Cabinet system should be abolished and replaced with committees representing all political parties. Jowett believed this would give more power to individual MPs. This proposal was unpopular with the leaders who felt it would undermine their power if the Labour Party formed the next government. This controversy brought Jowett into conflict with the party leader, Ramsay MacDonald. In an attempt to maintain party unity, Jowett agreed to resign as party Chairman.

Like many socialists Jowett opposed Britain's involvement in the First World War. He supported those who resisted conscription and demanded heavy taxation on wartime profits. Jowett also called on the British government to assume total control of the economy during the conflict. As Herbert Tracey pointed out: "That this would mean sacrificing his public position on the altar of popular passion and prejudice he was fully aware, but, believing in the ultimate righteousness of his attitude, he dared to pay the price, and, like the other few who thought with him when the view he took was to say the least unfashionable." In the 1918 General Election all those Labour MPs who opposed the war, including Jowett, Ramsay MacDonald, George Lansbury and Philip Snowden lost their seats.

Out of the House of Commons, Fred Jowett represented the Labour Party at several international conferences including the International Socialist Conference (Second International) in Switzerland in 1919 and the World Labour Conference in Poland in 1921.

In the 1922 General Election Jowlett was elected for East Bradford. In the 1923 General Election, the Labour Party won 191 seats. Although the Conservative Party had 258 seats, Herbert Asquith announced that the Liberal Party would not keep the Tories in office. If a Labour Government were ever to be tried in Britain, he declared, "it could hardly be tried under safer conditions". Ramsay MacDonald agreed to head a minority government, and therefore became the first member of the party to become Prime Minister. MacDonald appointed Jowett as his Commissioner of Works. One of his major achievements as a minister was to obtain the money needed to repair and modernize 60,000 government built houses.

In October 1924 MI5 intercepted a letter written by Grigory Zinoviev, chairman of the Comintern in the Soviet Union. The Zinoviev Letter urged British communists to promote revolution through acts of sedition. Vernon Kell, head of MI5 and Sir Basil Thomson head of Special Branch, told MacDonald that they were convinced that the letter was genuine. It was agreed that the letter should be kept secret but someone leaked news of the letter to the Times and the Daily Mail. The letter was published in these newspapers four days before the 1924 General Election and contributed to the defeat of MacDonald. The Conservatives won 412 seats and formed the next government.

Jowett lost his seat at East Bradford and while out of the House of Commons he took the opportunity to consider the future policies of the Independent Labour Party. In 1926 he produced a report Socialism in Our Time which argued for a national minimum income with full socialism as a long-term objective. Ramsay MacDonald refused to endorse the report and now out of line with the ILP decided to resign from the party.

Jowett returned to the House of Commons after the 1929 General Election but MacDonald did not offer him a place in his government. Jowett opposed the formation of the National Government and as a result lost his seat in the 1931 General Election. The following year Jowett and the Independent Labour Party disaffiliated from the Labour Party. It has been argued by J. A. Jowitt that: "He did not share some ILP members' beliefs that disaffiliation in a context of capitalist crisis would permit the party to become an effective revolutionary alternative to both the Communist and Labour parties... Politically, he remained committed to the parliamentary road to socialism, and was appalled by the ILP's subsequent flirtation with ultra-left tendencies and willingness to co-operate with communists."

The Independent Labour Party opposed Britain's involvement in the Second World War. He was very critical of the way the government ran the country during the conflict. Jowett claimed that the government's Equality of Sacrifice policy was just propaganda and pointed out that workers' wages were falling well behind increasing prices.

Frederick Jowett died at his home, 10 Grantham Terrace, Bradford, on 1st February 1944. He was survived by two daughters, a son, and five grandchildren.

Primary Sources

(1) Frederick Jowett, What Made Me a Socialist (1925)

My mother came from Derbyshire. Occasionally she would reveal incidents of her early life in my hearing, and they sank deeply into my mind, although she was quite unaware of the fact. It seemed natural that she should tell me also of Chartist meetings, although she was so young at the time and so little that for safety against the crowd she crept under the wagon from which the speeches were delivered. Early impressions of this sort must surely have made me a potential democrat in my very early years.

(2) In The Labour Leader newspaper, Katharine Glasier described meeting Fred Jowett as a young man (May, 1906).

Fred Jowett rose from his chair to greet me. This quiet-voiced, slightly-built, demurely-dressed (grey and black tie, starched collar), pale young man, with smooth black hair, correctly parted. Why - I told myself - he might have been a college student preparing for the Nonconformist ministry!

(3) Fenner Brockway, a member of the Independent Labour Party, later wrote about Jowett's achievements in Bradford.

In the winter of 1903-1904, following the Boer War, there was a severe depression in Bradford, and destitution was widespread. The school teachers in the poorer districts were in despair as they faced children pinched and emaciated through want of food. They asked the Education Committee to receive a deputation, and one after another told of the sorrowful condition of those in their charge. Moved by these stories, it was agreed, on the initiative of Jowett to appoint a Poor Children's special sub-committee with power to investigate and act. This investigation revealed 2,574 cases of underfed children in the schools. Of these 329 were stated to attend school without breakfasts. The Poor Children's sub-committee, impressed by the evidence of hunger, decided to provide school meals. This was the first decision by any local authority in Britain to assume public responsibility for feeding school children. Though he probably did not realise it at the time, this young Bradford Councillor was starting a movement destined to give food and health to millions. His action was hailed by Socialists throughout the country as a precedent and triumph. Keir Hardie sent him a prophetic message of congratulation, expressing the opinion that the Bradford decision would be historic, foreshadowing a time when the provision of school meals would pass into the common life of the people.

(4) In 1904 Fred Jowett persuaded Bradford Council to become the first in the country to assume responsibility for feeding school children. He explained in the council chamber why this measure was necessary.

That it is the duty of the community to see that all children are sufficiently fed. That voluntary effort is not able to feed children who are regularly or temporarily in need of food. That when children attend school insufficiently fed, it shall be the duty of the education Committee, acting on information supplied by the teachers, to feed these children.

It is not until the hunger-pangs are removed that people are able to think of something higher and to respond to the best impulses and appeals. Education on an empty stomach is a waste of money.

(5) The Daily News (20th April, 1911)

Mr. Jowett, the Labour Member, in a delightful little speech, very simple and human, introduced a Bill to enable local authorities to provide feeding for school children during holidays. Mr. Jowett showed a chart which illustrated how the weight of children at Bradford increases during term, but dwindles during holidays - a pathetic comment upon home life, when the wage fund only furnishes 1s. 9d. a week for food per child.

(6) Herbert Tracey, The Book of the Labour Party (1925)

An indefatigable worker where any deserving object is concerned, and a man of broad vision and high ideals, he has often been impelled by the dictates of his conscience to tread the lonely and unpopular path of the pioneer, in circumstances where a less steadfast man might have faltered. For him, however, the promptings of expediency and the temptation to compromise have held no attraction. Deep down in his heart, and clearly in his mind, was visualised quite early in his life the ultimate goal that emerged from his close study of social problems, and with all the zeal of the missionary he has kept his eyes resolutely trained on the objective ever since. A more comfortable passage through life he might easily have chosen-but that would have been at the sacrifice of his principles - a course he would never consider for a moment. Accordingly, as a young man, he relinquished an important commercial position in order that his mission of spreading the gospel of Socialism might be the more effectively pursued. From a similar motive he twice brought upon himself defeat in Parliamentary elections, when by trimming his sails he could have gained and retained his seat on those occasions. As a man of peace, he took his stand determinedly against both the Boer War and the Great War of more recent days. That this would mean sacrificing his public position on the altar of popular passion and prejudice he was fully aware, but, believing in the ultimate righteousness of his attitude, he dared to pay the price, and, like the other few who thought with him when the view he took was to say the least unfashionable, he has lived to see his opinions shared by the multitude.