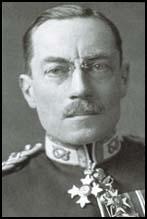

Vernon Kell

Vernon Kell, the son of Major Waldegrave Kell, of the South Staffordshire Regiment, and his wife, Georgiana Augusta Konarska, was born on 21st November 1873. As Richard Deacon has pointed out: "His mother was the daughter of a Polish count and as a boy he grew up with a wide circle of friends throughout Europe, and as a boy he learned to speak French, German, Italian and Polish."

Kell was such a talented linguist that at first his parents considered that he should be trained for the diplomatic service. However, in 1892 he entered the Sandhurst Royal Military College and two years later joined his father's old regiment.

As Kell could speak German, Italian, French and Polish he became an interpreter. In 1898 he studied Russian in Moscow. Afterwards he was posted to Shanghai to learn Chinese, but he became caught up in the Boxer Uprising and was unable to qualify as a Chinese interpreter until 1903.

Kell returned to London to a post in the German intelligence section of the War Office, but in 1905 he transferred to the Far Eastern section, and in 1907 moved to the Committee of Imperial Defence (CID), where he become Director of the Home Section of the Secret Service Bureau with responsibility for investigating espionage, sabotage and subversion in Britain. Later this organisation became known as MI5.

At the same time Mansfield Cumming became head of MI6, an organisation responsible for for secret operations outside Britain. Cumming feared that Kell would eventually become head of a unified intelligence unit. On 1st November 1909: "I am firmly convinced that Kell will oust me altogether before long. He will have quantities of work to show, while I shall have nothing. It will transpire that I am not a linguist, and he will then be given the whole job with a subordinate, while I am retired - more or less discredited."

Kell worked closely in this work with Basil Thomson, head of the Special Branch. Kell and Thomson decided to create a card-index system on all potential subversives. According to his biographer, Nicholas Hiley: "His chronic asthma and limited budget kept him from active enquiries, but he began the methodical collection of suspicious reports, and gradually gained the confidence of a select group of chief constables and government officials." It is claimed that by 1914 he had details of over 16,000 people. Hiley goes on to argue that " Kell was convinced that the German army was already planning invasion, and arranged for the secret registration of more than 30,000 resident aliens, who he was convinced formed the basis of a network of military agents and saboteurs."

On the outbreak of the First World War Kell joined forces with Eric Holt-Wilson and Basil Thomson to draft The Defence of the Realm Act (DORA). This was an attempt "to prevent persons communicating with the enemy or obtaining information for that purpose or any purpose calculated to jeopardise the success of the operations of His Majesty's Forces or to assist the enemy." This legislation gave the government executive powers to suppress published criticism, imprison without trial and to commandeer economic resources for the war effort. During the war publishing information that was calculated to be indirectly or directly of use to the enemy became an offence and accordingly punishable in a court of law. This included any description of war and any news that was likely to cause any conflict between the public and military authorities.

By 1914 Kell had a staff of four officers, one barrister, two investigators and seven clerks. This enabled MI5 to collect a great deal of information of spies in Britain. On the outbreak of the First World War MI5 officers arrested 22 German agents. Over the next year another seven spies were caught. Eleven men were executed, as was Sir Roger Casement, who was found guilty of treason in 1916.

When conscription was introduced in May 1916 Kell argued that groups such as Union of Democratic Control and the No-Conscription Fellowship should be "classed as pro-German" and MI5 began the intensive surveillance of more than 5,000 individuals. According to Nicholas Hiley: "By October 1917 its registry contained almost 40,000 personal files, and 1 million cross-index cards, and its principal work had become the collection and analysis of information on a vast range of innocent individuals and organizations."

At the end of the First World War Kell had a staff of 850 and an annual budget of £100,000. However, in 1919 some of MI5's responsibilities transferred to the Special Branch and Kell's budget was cut to £35,000, his staff was reduced to just thirty, and his duties were confined to counter-espionage and the combating of communism within the armed forces. His biographer has argued: "The post-war red scare seemed ideal for MI5, as it demanded the cross-checking of vast numbers of suspects, and apparently confirmed that democracy required strengthening from outside by determined men such as Kell. However, financial constraints prevented MI5 from recruiting young staff and forced Kell to rely heavily on personal links with business and political organizations, often on the far right."

Kell decided to work with George Makgill, who had joined forces with William Reginald Hall and a group of industrialists to form the Economic League, an organisation dedicated to opposing what they saw as subversion and action against free enterprise. John Baker White, a future Conservative MP, was brought in the run the organisation. White called Makgill "perhaps the greatest Intelligence officer produced in this century."

Makgill also set up the Industrial Intelligence Bureau (IIB). According to the author of Churchill's Man of Mystery (2009), it was "financed by the Federation of British Industries and the Coal Owners' and Shipowners' Associations, to acquire intelligence on industrial unrest arising from the activities of Communists, Anarchists, various secret societies in the UK and overseas, the Irish Republican Army (IRA) and other subversive organisations." Makgill recruited his agents from far-right organisations such as British Fascisti (BF). This included Maxwell Knight, the organization's Director of Intelligence. Another agent was W. B. Findley, who used the name Jim Finney, to infiltrate the Communist Party of Great Britain.

Another of Makgill's agents was Kenneth A. Stott, who recruited spies from within the trade union movement. In September 1922, Stott claimed that he attended a meeting in Cologne of the Deutscher Uberseedienst (German Overseas Service). Stott claimed the organisation had "its own secret service, which sent couriers to collect information, working through extremists, Trade Unions and labour movements".

Vernon Kell introduced George Makgill to Desmond Morton, head of the Secret Intelligence Service's Section V, dealing with with counter-Bolshevism. Morton wrote to Makgill on 2nd February 1923, that "anything I can find out is always at your disposal". Morton was not always impressed with the information provided by Makgill's agents. On 28th May 1923 Morton wrote to Makgill: "They are the kind of reports which a policeman would put up to his inspector when told to watch people, but not one statement really carries us any further. All the names mentioned are the names of people known to be interested in Communist or Irish intrigues, and... there is nothing to show what these intrigues are, which is the important thing."

In the 1923 General Election, the Labour Party won 191 seats. Although the Conservatives had 258, Ramsay MacDonald agreed to head a minority government, and therefore became the first member of the party to become Prime Minister. As MacDonald had to rely on the support of the Liberal Party, he was unable to get any socialist legislation passed by the House of Commons. The only significant measure was the Wheatley Housing Act which began a building programme of 500,000 homes for rent to working-class families.

Vernon Kell, like other members of establishment, was appalled by the idea of a Prime Minister who was a socialist. As Gill Bennett pointed out: "It was not just the intelligence community, but more precisely the community of an elite - senior officials in government departments, men in "the City", men in politics, men who controlled the Press - which was narrow, interconnected (sometimes intermarried) and mutually supportive. Many of these men... had been to the same schools and universities, and belonged to the same clubs. Feeling themselves part of a special and closed community, they exchanged confidences secure in the knowledge, as they thought, that they were protected by that community from indiscretion."

Two days after forming the first Labour government Ramsay MacDonald received a note from General Borlass Childs of Special Branch that said "in accordance with custom" a copy was enclosed of his weekly report on revolutionary movements in Britain. MacDonald wrote back that the weekly report would be more useful if it also contained details of the "political activities... of the Fascist movement in this country". Childs wrote back that he had never thought it right to investigate movements which wished to achieve their aims peacefully. In reality, MI5 was already working very closely with the British Fascisti, that had been established in 1923. Maxwell Knight was the organization's Director of Intelligence. In this role he had responsibility for compiling intelligence dossiers on its enemies; for planning counter-espionage and for establishing and supervising fascist cells operating in the trade union movement. This information was then passed onto Vernon Kell.

In September 1924 MI5 intercepted a letter signed by Grigory Zinoviev, chairman of the Comintern in the Soviet Union, and Arthur McManus, the British representative on the committee. In the letter British communists were urged to promote revolution through acts of sedition. Hugh Sinclair, head of MI6, provided "five very good reasons" why he believed the letter was genuine. However, one of these reasons, that the letter came "direct from an agent in Moscow for a long time in our service, and of proved reliability" was incorrect.

Vernon Kell and Sir Basil Thomson the head of Special Branch, were also convinced that the Zinoviev Letter was genuine. Kell showed the letter to Ramsay MacDonald, the Labour Prime Minister. It was agreed that the letter should be kept secret but someone leaked news of the letter to the Times and the Daily Mail. The letter was published in these newspapers four days before the 1924 General Election and contributed to the defeat of MacDonald and the Labour Party.

In a speech he made on 24th October, Ramsay MacDonald suggested he had been a victim of a political conspiracy: "I am also informed that the Conservative Headquarters had been spreading abroad for some days that... a mine was going to be sprung under our feet, and that the name of Zinoviev was to be associated with mine. Another Guy Fawkes - a new Gunpowder Plot... The letter might have originated anywhere. The staff of the Foreign Office up to the end of the week thought it was authentic... I have not seen the evidence yet. All I say is this, that it is a most suspicious circumstance that a certain newspaper and the headquarters of the Conservative Association seem to have had copies of it at the same time as the Foreign Office, and if that is true how can I avoid the suspicion - I will not say the conclusion - that the whole thing is a political plot?"

After the election it was claimed that two of MI5's agents, Sidney Reilly and Arthur Maundy Gregory, had forged the letter and that Major George Joseph Ball (1885-1961), a MI5 officer, leaked it to the press. In 1927 Ball went to work for the Conservative Central Office where he pioneered the idea of spin-doctoring. Later, Desmond Morton, who worked under Hugh Sinclair, at MI6 claimed that it was Stewart Menzies who sent the Zinoviev letter to the Daily Mail.

Kell complained to the Secret Service Committee that, because of his diminished resources, "he had no agents in the accepted sense of the word, but only informants, though he might employ an agent for a specific purpose, if necessary, in which case he would consult Scotland Yard about him, if he were in doubt as to his character, or he might even borrow a man from Scotland Yard.''

Kell continued to work closely with the British government and in October 1931 MI5 was given responsibility for investigating communism throughout the United Kingdom, using staff transferred from the Special Branch and MI6. In 1934 he was given the task of investigating fascism. Nicholas Hiley has pointed out: "This produced a rapid increase in MI5's resources and, although in 1935 Kell's staff numbered just over ninety, within four years it had grown to 330, with an annual budget of more than £90,000 and a secret registry containing some 250,000 personal files."

MI5 managed to infiltrate the British Union of Fascists. However, Kell dismissed the idea that Oswald Mosley posed a serious threat to the government. In October 1934, Kell reported to the Home Office: "It is becoming increasingly clear that at Olympia Mosley suffered a check which is likely to prove decisive. He suffered it, not at the hands of the Communists who staged the provocations and now claim the victory, but at the hands of Conservative MPs, the Conservative Press and all those organs of public opinion which made him abandon the policy of using his Defence Force to overwhelm interrupters."

By the outbreak of the Second World War, the British government had began to doubt the competence of the leadership of intelligence services. Winston Churchill was especially critical of MI5 and was furious when an explosion in his constituency took place at the Royal Gunpowder factory at Waltham Abbey. However, as Christopher Andrew has pointed out: "Sabotage was rumoured and Chief Inspector William Salisbury, later of the Murder Squad, launched an investigation. His conclusion, with which the M15 counter-sabotage unit and Detective Chief Inspector Williams of Special Branch agreed, was that none of the three explosions which occurred on 18 January and killed five workers were caused by sabotage."

Churchill became prime minister in May 1940, and on 10th June he was sacked. So also was his deputy, Eric Holt-Wilson. The following day, his wife, who managed the canteen at Wormwood Scrubs, gathered the staff together and told them bitterly, "Your precious Winston has sacked the General."

Major-General Vernon Kell died at his rented cottage, Stonepits, Emberton, Olney, in Buckinghamshire, on 27th March 1942.

Primary Sources

(1) Richard Deacon, Spyclopaedia (1987)

He (Vernon Kell) made full use of his linguistic talents in the Army when, as a captain in the South Staffordshire regiment, he studied Russian in Russia and Chinese in China, passing his examinations as an interpreter in each language. He saw service in the Boxer Rebellion in China and had been Intelligence Officer on General Lorne Campbell's staff in Tientsin. Ill-health interrupted his military career and, four years after being made a staff captain in the German section of the War Office in 1902, he was retired from the Army, but given the job of organizing from scratch M05, which later became M15. A lesser man than Kell might have lost heart in the first six months of this job. He was told to keep expenses down and, when he asked for a clerk, there were immediate protests. Eventually he was given one assistant and gradually he produced a mass of impressive reports which showed that Britain urgently needed a strong counter-espionage unit.

Kell's greatest initial success was in winning the cooperation of the police and working effectively with Scotland Yard. He frequently travelled to distant parts of the country to make personal investigations. Quickly he discovered that the biggest obstacle to spy-catching was the outdated Official Secrets Act. He pointed out to the War Office that in case after case Germans had been found gathering information about ships, factories and harbours, but that nothing could be done to check this because in law the spies were committing no offence. Vigorously he pressed for changes in the law, which ultimately were made. He also applied to the Home Secretary for permission to intercept the mail of suspected German spies, and it was as a result of this that a barber known as Karl Gustav Ernst living in the Caledonian road was discovered to be acting as a "post office" for the German espionage machine.

Gradually Kell won his battle to expand M15, and he began to chalk up some successes. The barber was trapped and caught and in 1911 an officer of the German Hussars was arrested at Plymouth. By the eve of World War I he had found an extensive German spy network in Britain and his staff had been increased to include four officers, one barrister, two investigators and seven clerks. M15's offices were transferred to the basement of the Little Theatre in John Street, off the Strand. As a result of the hard work put in by this small unit, when war was declared in 1914, twenty-two German spies were rounded up in Britain and arrested within a single day. This meant that for the best part of a year Germany had no effective spy service in Britain. The following year a further seven spies were caught and from then on M15's future was guaranteed. From 1906 to 1939 Kell remained in charge of the organization, a service record unsurpassed in modern times.

The troubles in Ireland occupied Kell's time in the years immediately after the war. Later the threat of subversion from Soviet sources became the major problem. By the time World War II began, Kell had achieved the rank of Major-General and supervised a staff of nearly 6000. He had not only infiltrated the Communist and Fascist ranks in Britain, but had most effectively penetrated the organization which was handling recruitment for the Spanish Republican Army. The result was that when war broke out again, some 6000 people were rounded up and interned as suspects, though only thirty-five of these were Britons. Early in 1940 Kell was forced to resign owing to ill-health, having carried on indomitably for many years, despite suffering which would have defeated a lesser man.

(2) Mansfield Smith-Cumming, memo (1st November 1909)

Cannot do any work in office. Been here five weeks, not yet signed my name. Absolutely cut off from everyone while there, as cannot give my address or be telephoned to under my own name. Have been consistently left out of it since I started. Kell has done more in one day than I have in the whole time...

The system has been organised by the Military, who have just had control of our destinies long enough to take away all the work I could do, hand over by far the most difficult part of the work (for which their own man is obviously better suited) and take away all the facilities for doing it.

I am firmly convinced that Kell will oust me altogether before long. He will have quantities of work to show, while I shall have nothing. It will transpire that I am not a linguist, and he will then be given the whole job with a subordinate, while I am retired - more or less discredited.

(3) Mansfield Smith-Cumming, diary entry (17th March, 1910)

Called on Kell at his request handed over my small safe and the keys to my desk to his Clerk... He asked me if I should object to his coming next door, but t told him that I thought it would interfere with my privacy in my own flat and I begged he would not go forward with any such scheme. I would rather he were not in this immediate neighbourhood at all.

(4) Report and Proceedings of a Sub-Committee of the Committee of Imperial Defence (7th April, 1919)

Colonel Kell said that it had occurred to him that Parliamentary opposition to the Secret Service vote would be greatly reduced if he were to take the Labour Members into our confidence to the extent of showing some of the most prominent of them a little of the work which had been done during the War. He could easily let them see many parts of his work which were not really very secret, but which were impressive as showing good results. He thought that this would help, not only to make them interested in the continuance of the work, but would also tend to dispel the feeling which appeared to be prevalent in many quarters that Secret Service funds were used to spy upon Labour in this country.

(5) Eric Holt-Wilson, memo to Vernon Kell (1920)

Despite statements to the contrary in the press and elsewhere, Sir Basil Thomson's organization has never actually detected a case of espionage, but has merely arrested and questioned spies at the request of MI5, when the latter organization, which had detected them, considered that the time for arrest had arrived. The Army Council are in favour of entrusting the work to an experienced, tried and successful organization rather than to one which has yet to win its spurs.

Sir Basil Thomson's existing higher staff consists mainly of ex-officers of MI5 not considered sufficiently able for retention by that Department. The Army Council are not satisfied with their ability to perform the necessary duties under Sir Basil Thomson's direction, and they are satisfied that detective officers alone, without direction from above, are unfitted for the work.

(6) Winston Churchill, memorandum circulated to the cabinet (March, 1920)

With the world in its present condition of extreme unrest and changing friendships and antagonisms, and with our greatly reduced and weak military forces, it is more than ever vital to us to have good and timely information. The building up of Secret Service organisations is very slow. Five or ten years are required to create a good system. It can be swept away by a stroke of a pen. It would in my judgment be an act of the utmost imprudence at the present time.

(7) Christopher Andrew, The Defence of the Realm (2009)

One MI5 officer, Captain (later Major) Herbert "Con" Boddington, had, however, succeeded in joining the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB) in 1923 on Kell's instructions. On entering MI5 in 1923 at the age of thirty, despite being wounded in the war, Boddington had listed as his recreations "All outdoor games. Principally boxing, rowing and running." Unusually for an MI5 recruit, however, he had added: "Can act. Have played light comedian [sic] both at home and abroad." Boddington also claimed "literary experience", which included writing stories for silent films." At least some of these skills were probably of assistance in passing himself off as a Communist.

Kell's search for informants to compensate for his post-war lack of an agent network led him to co-operate with Sir George Makgill, a businessman with ultra-conservative views and a deep-seated dislike of trade unions. At the end of the war, with the support of a group of like-minded industrialists, Makgill set up a private Industrial Intelligence Bureau (IIB), financed by the Federation of British Industries and the Coal Owners' and Shipowners' Associations, to acquire intelligence on industrial unrest arising from subversion by Communists, anarchists, the Irish Republican Army (IRA) and others. From an early stage Makgill was in contact with Kell, who claimed that he had helped Makgill found "an organisation of a secret nature somewhat on Masonic lines" - probably a reference to the IIB. (Unlike Kell, Makgill and his son Donald were both prominent Freemasons.) Before joining MI5, Boddington had worked for the IIB and remained in touch with, notably, Makgill's agent, "Jim Finney", who, like Boddington, succeeded in joining the CPGB.

(8) Vernon Kell, report to the Home Office (October 1934)

It is becoming increasingly clear that at Olympia Mosley suffered a check which is likely to prove decisive. He suffered it, not at the hands of the Communists who staged the provocations and now claim the victory, but at the hands of Conservative MPs, the Conservative Press and all those organs of public opinion which made him abandon the policy of using his "Defence Force" to overwhelm interrupters.

(9) Christopher Andrew, The Defence of the Realm (2009)

As a secret organization MI5 could not publicly claim credit for its part in the capture of German spies. The more flamboyant Thomson, already well used to publicizing his achievements, could and did. In the process he earned the collective enmity of most of M15. Reginald Drake, head of counter-espionage in MI5 until 1917, wrote later to Blinker Hall: "As you know B.T. did not know of the existence, name or activity of any convicted spy until I told him; but being the dirty dog he was he twisted the facts to claim that he alone did it." There was, inevitably, some overlap in the activities of MI5 and the Special Branch which added further to the rivalry between them. Eddie Bell, who was responsible for intelligence liaison at the US embassy, wrote after the war that when the embassy wished to make inquiries about people claiming American citizenship arrested on suspicion of being German spies "it became almost a question of flipping a coin to decide whether application for information should be made to Scotland Yard, the Home Office or MI5." Blinker Hall had much greater sympathy for the flamboyant Thomson than for the retiring Kell. Bell reported "considerable jealousy between the Intelligence Department of the War Office and the Admiralty, the latter affecting to despise the former, particularly MI5, whom they always described as shortsighted and timorous... While Thomson enjoyed the limelight, Kell shunned it. His only known publication is a letter to a newspaper on the behaviour of the lapwing.

In the later stages of the war, Thomson was to emerge as the most formidable rival encountered by Kell in his thirty-one years as director. In the power struggle which ensued, Kell's Bureau became a victim of its own successes. Had German espionage remained a serious apparent threat throughout the war or Germany succeeded in launching a major sabotage campaign in Britain, Kell would have found it much easier to retain the lead domestic intelligence role. But during the second half of the war, with government now more concerned with subversion than with espionage, it was easier for Thomson than for Kell to gain the ear of ministers.

(10) Christopher Andrew, The Defence of the Realm (2009)

The reason for the friction is almost impossible to fathom but Kell undoubtedly mistrusted Churchill, perhaps it went back to Churchill's attempts to merge M15 and SIS in the Twenties. Kell once claimed to have refused a pre-war request for intelligence information from Churchill but that is unsubstantiated. It could, however, be argued that because Desmond Morton had had to rely on Maxwell Knight for "situation reports" he was obviously not obtaining them from the horse's mouth.

Certainly it had been a bad twelve months for M15 and they had come in for more than their fair share of criticism. Two particular incidents had attracted an embarrassing amount of adverse press coverage even though, like the sabotage of Oleander, War Afridi, HMS Cumberland and L-54 before the war... they had nothing to do with M15. As before they were concerned with the Royal Navy but some felt that Churchill might have marked them all down as Security Service blunders and as further examples of their inefficiency.

The first incident thought to have broken Churchill's patience was the audacious German attack on Scapa Flow on 14 October, 1939. The loss of the Royal Oak with 834 hands was a savage blow to the morale of the country and the Navy. For quite unjustified reasons M15 were blamed for much of the Admiralty's incompetence. A U-boat captain named Gunther Prien succeeded in picking his way through the anti-submarine defences around the Navy's refuge in the Orkneys and proceeded to select an enviable target. The Admiralty held an enquiry and NID sent sleuths up to Kirkwall to investigate rumours of German spies, but failed to get any evidence. The results of the official enquiry were eventually published and it was obvious that the local precautions against an underwater attack were negligently inadequate.

On the day after the disaster a blockship arrived at Scapa Flow. It was to have been sunk in the narrow channel negotiated by U-47 the previous afternoon. A long delay occurred before the Admiralty were even sure that the Royal Oak had been sunk by a submarine. Sabotage was a popular theory. No one ever denied that espionage was at the bottom of it all so journalists had a field-day. After the war several accounts were published of a mysterious Nazi watchmaker who had vanished from his shop in the Orkneys the day of the attack! It was, of course, all eye-wash, though to their credit M15 did turn up a suspicious Italian photographer who ran a camera shop in Inverness. There was nothing to suggest that he was in any way connected with the disaster at Scapa Flow but he was interned anyway.

The second incident that gave M15 a bad press was an explosion in Churchill's constituency at the Royal Gunpowder factory at Waltham Abbey in January 1940. Sabotage was rumoured and Chief Inspector William Salisbury, later of the Murder Squad, launched an investigation. His conclusion, with which the M15 counter-sabotage unit and Detective Chief Inspector Williams of Special Branch agreed, was that none of the three explosions which occurred on 18 January and killed five workers were caused by sabotage. The announcement of their findings received very little coverage compared to the headlines that the incident provoked at first. The investigation left the First Lord of the Admiralty unimpressed.

Whatever the background, the circumstances of Kell's abrupt dismissal are clear. He was summoned to Sir Horace Wilson's office on Monday, 10 June, and left, a broken man, a short time later. Kell broke the news to his Deputy D-G, Eric Holt-Wilson, the same evening at his club, and promptly received his resignation. That night Kell made this bitter entry in his personal diary: "I get the sack from Horace Wilson, 1909-1945."

Officially retired in 1923 and confirmed in that year by the London Gazette, Kell now genuinely relinquished a post he had held since 1909. There was no obvious successor so Brigadier Harker, the Director of `B' Division, was promoted Deputy D-G with the rank of Acting Director-General. In his place Guy Liddell was appointed Director of "B", a post he was to hold until 1947.

In fact the real power of MI5 was soon to be invested in the Security Executive, the recently formed Home Defence Executive off-shoot. Churchill's choice for Chairman was Lord Swinton, previously Sir Philip Cunliffe-Lister and Chamberlain's Air Minister. His powerful committee was established in great secrecy in Kinnaird House, Pall Mall, and Sir Joseph Ball, another senior figure in the Conservative Party, was appointed Deputy Chairman. The Security Executive was also served by two Joint Secretaries, William Armstrong (later Lord Armstrong), a civil servant from the Board of Education, and Kenneth Diplock (now Lord Diplock), an Oxford-educated barrister.