House of Lords

Kings in the Middle Ages would often consult their tenants-in-chief before making important decisions. These men were usually called to appear before the king during religious festivals (Christmas, Easter, Whitsun). Some of the men who attended these meetings were given specific jobs to perform for the king, for example, to act as treasurer. Some kings tended to ignore the advice of the barons. When this led to bad decisions the barons became angry. This is one of the reasons why the barons rebelled against King John and made him sign the Magna Carta.

Henry II was another king who tended to ignore the advice of his barons. Under the leadership of Simon de Montfort, the barons rebelled. After the Battle of Lewes in 1264, Simon de Montfort took control of the council which had now become known as Parliament (parler was Norman French for talk). The following year Simon de Montfort expanded Parliament by inviting representatives from the shires and towns to attend the meetings.

In 1275 Edward I called a meeting of Parliament. As well as his tenants-in-chief, Edward, like Simon de Montfort before him, invited representatives from every shire and town in England. As well as his tenants-in-chief, Edward invited representatives from every shire and town in England. These men were elected as representatives by the people living in the locality. When the representatives arrived they met in five different groups: (1) the prelates (bishops and abbots); (2) the magnates (earls and barons); (3) the inferior clergy; (4) the knights from the shires; (5) the citizens from the towns.

At these meetings Edward I explained about his need for money. Eventually the representatives agreed that people should pay the king a tax that amounted to a fifteenth of all their movable property. It was also agreed that a custom duty of 6s. 8d. should be paid on every sack of wool exported. As soon as agreement was reached about taxes, groups 3, 4 and 5 (the commons) were sent home. The representatives then had the job of persuading the people in their area to pay these taxes. The king then discussed issues such as new laws with his bishops, abbots, earls and barons (the lords).

After this date, whenever the king needed money, he called another Parliament. Henry VIII enhanced the importance of Parliament by his use of it during the English Reformation. In 1547 the king gave permission for members of the commons to meet at St. Stephen's Chapel, in the Palace of Westminster. In the 15th century the House of Lords was the Upper House and the House of Commons the Lower House. Membership of the House of Lords was made up of the Lords Spiritual (two Archbishops, 24 Diocesan Bishops) and the Lords Temporal which were divided into three groups: hereditary peers, peers granted peerages by the sovereign on the advice of the Prime Minister, and the Law Lords, who are recruited from the ranks of Britain's High Court Judges.

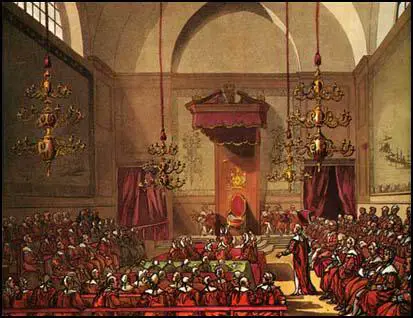

In 1834 the chapel and most of the Old Palace of Westminster was destroyed by fire. The new Palace of Westminster was designed by Sir Charles Barry and Augustus Welby Pugin. The House of Lords is slightly smaller than the House of Commons and only seats 250 members. However, Barry and Pugin made the interior more impressive than the commons with the seats upholstered in red leather. The chamber is dominated by an ornate royal throne where the sovereign sits during the opening of Parliament.

Tom Paine stated in his book, The Rights of Man (1791): "What is government more than the management of the affairs of a Nation? It is not, and from its nature cannot be, the property of any particular man or family, but the whole community. The romantic and barbarous distinction of men into Kings and subjects, though it may suit the condition of courtiers, cannot that of citizens." The abolition of the House of Lords has been advocated by the left ever since Paine wrote his book over 220 years ago.

This became a major issue in 1884 when the un-elected chamber blocked moves by William Gladstone and his Liberal government to give the vote to all adult males. After lengthy negotiations Gladstone eventually accepted changes and the 1884 Reform Act was passed by the lords. However, this legislation meant that all women and 40% of adult men were still without the vote.

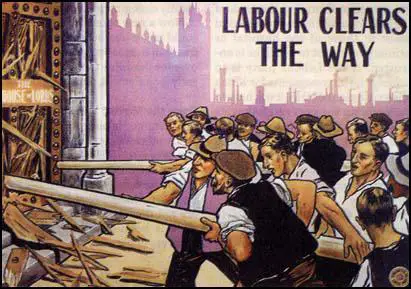

All the early left-wing organizations, the Social Democratic Federation, the Fabian Society, and the Independent Labour Party, argued for an elected second-chamber. On 27th February 1900, representatives of all the socialist groups in Britain formed the Labour Party under the leadership of Keir Hardie. Until he died fifteen years later, Hardie argued for the removal of an institution that he saw as a "betrayal of the core democratic principle that those who make the laws of the land should be elected by those who must obey those laws".

The Liberal Party also became hostile to the House of Lords after it attempted to block reforms initiated by the Chancellor of the Exchequer, David Lloyd George. This included the People's Budget, which imposed higher taxes on unearned income, and the Old Age Pensions Act. Lloyd George reacted by touring the country making speeches in working-class areas on behalf of the budget and portraying the nobility as men who were using their privileged position to stop the poor from receiving their old age pensions. After a long struggle with the Lords the government finally got his budget through parliament.

With the House of Lords extremely unpopular with the British people, the Liberal government decided to take action to reduce its powers. The 1911 Parliament Act drastically cut the powers of the Lords. They were no longer allowed to prevent the passage of "money bills" and it also restricted their ability to delay other legislation to three sessions of parliament.

The Labour Party has always said it wants to abolish the Lords but never acted upon it. Martin Pugh, the author of Speak for Britain: A New History of the Labour Party (2011) points out: "In 1922 the party had almost no representation in the House of Lords and was officially committed to abolishing the hereditary peerage." Arthur Ponsonby introduced a bill to abolish hereditary titles altogether but there were already signs of compromise.

"While Tory propaganda strove to depict Labour as subversive and anti-Establishment, leading politicians were busy defusing the charge." Leading Labour politicians such as Ramsay MacDonald, John R. Clynes, George Barnes, Jimmy Thomas, Philip Snowden and Arthur Henderson attended royal weddings and Buckingham Palace garden parties. The idea of abolishing the House of Lords was quietly dropped and after the 1929 General Election MacDonald appointed a member of the upper chamber, Earl De La Warr, to his government, even though he admitted he was not a party member.

Attempts were made to reintroduce this policy. At the 1933 Labour Party Conference Stafford Cripps advocated that the next Labour government would immediately abolish the House of Lords, and pass an Emergency Act "to take over or regulate the financial machine, and put into force any measure that the situation may require for the immediate control or socialisation of industry and for safeguarding the supply of food and other necessaries." Cripps pointed out that it was completely unacceptable to continue a system that allows the rich to veto laws that they do not like. However, this important motion was never voted on.

Clement Attlee became the new leader of the Labour Party in 1935 and showed no interest in abolishing the House of Lords. Harold Laski continued to denounce it as "an indefensible anarchronism" and that its existence was not "compatible with the objective of Socialism". Attlee was unimpressed with this argument and when he became prime minister following the 1945 General Election he created no fewer than eighty-two hereditary peerages. He symbolised Labour's new stance by accepting an earldom when he retired in 1955.

In the 1977 Labour Party Conference decided by 6,248,000 votes to 91,000 to include the abolition of the House of Lords in Labour's election manifesto. Constitutionally any conference resolution that received two-thirds of the vote had to be included in the manifesto. James Callaghan, ignored the constitution and the abolition of the Lords did not go into the 1979 manifesto. On his retirement in 1987, he was elevated to the House of Lords as Baron Callaghan.

In March, 1994, Tony Blair was introduced to Michael Levy at a dinner party at the Israeli embassy in London by diplomat Gideon Meir. Levy was a retired businessman who now spent his time raising money for Jewish pressure-groups. Levy has been described by The Jerusalem Post as "undoubtedly the notional leader of British Jewry".

After this meeting, Levy acquired a new job, raising money for Blair. According to Robin Ramsay, the author of The Rise of New Labour, Levy raised over £7 million for Blair. In an article by John Lloyd published in the New Statesman on 27th February, 1998, the main suppliers of this money included Sir Emmanuel Kaye, a millionaire British industrialist and former funder of the Conservative Party, Sir Trevor Chin (Lex Garages and RAC), Maurice Hatter (IMO Precision Group) Alexander Bernstein (Granada Group) and Robert Gavron (Octopus Publishing).

In April, 1994, John Smith died and Blair won the leadership contest. With Levy’s money, Blair appointed Jonathan Powell as his Chief of Staff. A retired diplomat, Powell was not a member of the Labour Party. In fact, his brother, Charles Powell, was a leading advisor to Margaret Thatcher when she was in government. Alastair Campbell was the other man brought into his private office with Levy’s money. Powell and Campbell were later to become key figures in the later invasion of Iraq. It is of course a pure coincidence that this decision reflected the thinking of Israel’s government.

The Labour Party, when elected to power in 1997, promised to introduce legislation that would make the House of Lords an elected second chamber. However, Tony Blair, the prime minister changed his mind and instead called for a fully appointed House of Lords. During his first term of office, Blair created 203 life peers. Many of these were people who had provided funds for Blair. This included his chief fundraiser, Baron Levy, of Mill Hill. He made his maiden speech on 3rd December 1997, but since then he has not spoken in a debate at the House of Lords.

Blair was accused in 1999 by William Hague, the Leader of the Conservative Party and the Leader of the Opposition, of replacing the House of Lords with a "house of cronies." However, it was not until 2005 that Blair's appointments gave the Labour Party a majority in the House of Lords. It is claimed that by the time he resigned in 2007, Blair's Labour Party received over £100 million from Lord Levy and his friends.

Primary Sources

(1) Daniel Defoe, A Tour Through the Whole Island of Great Britain (1724)

The House of Lords is a venerable old place, indeed; but how mean, how incoherent, and how strained are the several avenues to it, and rooms about it? The matted gallery, the lobby, the back ways the king goes to it, how short are they all of the dignity of the place, and the glory of a King of Great Britain with the Lords and Commons, that so often meet there?

(2) William Pyne, The Microcosm of London (1808)

The tapestry of the old House of Lords is used to decorate the present, and is set off with large frames of brown stained wood. The old canopy of state is placed at the upper end of the room, with the addition of the arms of the United Kingdom, painted upon silk.

(3) Tom Paine, The Rights of Man (1791)

What is government more than the management of the affairs of a Nation? It is not, and from its nature cannot be, the property of any particular man or family, but the whole community. The romantic and barbarous distinction of men into Kings and subjects, though it may suit the condition of courtiers, cannot that of citizens.

We have heard The Rights of Man called a levelling system; but the only system to which the word levelling is truly applicable is the hereditary monarchical system. It is a system of mental levelling. It indiscriminately admits every species of character to the same authority. Vice and virtue, ignorance and wisdom, in short, every quality, good or bad, is put on the same level. Kings succeed each other, not as rationals, but as animals. In reverses the wholesome order of nature. It occasionally puts children over men, and the conceits of nonage over wisdom and experience. In short we cannot conceive a more ridiculous figure of government, than hereditary succession.

It is inhuman to talk of a million sterling a year, paid out of the public taxes of any country, for the support of any individual, while thousands who are forced to contribute thereto, are pining with want, and struggling with misery. What is called the splendour of a throne is no other than the corruption of the state. It is made up of a band of parasites, living in luxurious indolence, out of the public taxes.

(4) Robin Cook, speech, House of Commons (4th February, 2003)

I am very much committed that the House should seize what is a unique and historic opportunity to make clear its preference. If we are serious about reform, then we should have a largely or wholly elected second chamber. In the modern world, legitimacy is conferred by democracy. If we want the public to trust politicians, then we must trust the people who elect politicians.

(5) Douglas Hogg, speech, House of Commons (4th February, 2003)

Those who argue the case for an appointed second chamber normally concede that it will lack the legitimacy of an elected one. I find it extraordinary that at the start of the 21st century we should be contemplating the creation of a political structure which, by its very act of creation, will lack the political legitimacy required to give it either authority or indeed survival.

(6) Peter Wishart, speech, House of Commons (4th February, 2003)

Surely there is something wrong when the Prime Minister won't even support his own manifesto.

(7) Polly Toynbee, The Guardian (5th February, 2003)

There is much to be said for the Blair plan for an entirely appointed House of Lords. Unfortunately all of it is bad. Oligarchy has its charms - but since the days of Cromwell those charms have eluded all but the oligarchs, where in the Lords gerontocracy masquerades as experience, bishops with empty pews represent an empty shell of faith and yesteryear's politicians are pensioned into a golden dotage. No surprise then that the old turkeys on the red benches did not vote for winter festival but for their own perpetuity without the inconvenience of a trip to the hustings where most could be guaranteed a roasting.

Hybridity, they clucked, would be a very bad thing and they are right about that: there would be a strange divide between the legitimate and the illegitimate peers in any future House, part-elected and part-appointed. One hundred per cent democracy was the only possible outcome. How extraordinary it seems in the 21st century that, as we are about to go to war, yet again we are trumpeting for the democratic rights of far-away people, and still find it necessary to quote Winston Churchill: "Democracy is the worst form of government, except all those other forms that have been tried from time to time". How can Labour have let itself be out-reformed by Iain Duncan Smith - even if he commanded as little obedience as Blair.

This progressive reform has waited a century: now the House of Lords will remain the laughing stock of the western world. Now the chance of reform has collapsed, all due to a moment of madness in which a prime minister already accused of anti-democratic instincts has done himself needless harm. Was it the insouciance of a mind floating somewhere between Washington and Baghdad?