Arthur J. Cook

Arthur James Cook, the son of a soldier, was born in Wookey, Somerset, on 22nd November 1883. Cook was raised as a Baptist and by the age of sixteen he acquired the title of "the boy preacher". A devout teetotaller he was attracted to Socialism as he saw it as a natural expression of his Christianity. (1)

In 1899, at the age of seventeen, Cook moved to Merthyr Tydfil to seek employment in the coal mines. Paul Davies, the author of A. J. Cook (1987), has argued: "From Somerset alone in the 1890s an average of a thousand boys a year were sucked into Glamorgan by the attraction of pit work and higher earnings." (2)

On his first day in the pits, a fall of rock killed the man working next to him. He helped carry the man's body to the surface and then home to his wife and children. Cook made good progress at his work and graduated quickly from labourer to haulier, and then went on to become a collier. He earned enough to send money home to his mother. This achievement was made easier by Cook's teetotalism. He was now in a position to marry Annie Edwards and with the £100 in his savings he was able to furnish a small house in Porth.

In 1905 Cook joined the Independent Labour Party (ILP), and campaigned for its candidates in the 1906 General Election. Cook was also an active member of the South Wales Miners Federation. He also preached at his local Baptist chapel and became a Sunday School teacher and deacon. At the time Cook was more interested in religion than politics: "To me, an ardent young preacher... was all I thought worth living for; it filled my thoughts and kept me tense and absorbed." (3)

Arthur J. Cook: Trade Union Activist

Arthur J. Cook gradually became more interested in trade union matters. His front room was converted on Saturday mornings into a miners' consultation office. Cook, who could read and write, helped his fellow miners to fill in the complicated forms necessary to claim their compensation entilements. In 1906 he resigned from the chapel. As Paul Foot has pointed out: "The conditions in the pits soon persuaded him that heaven would have to wait. What mattered immediately was a better life on earth, and under it". (4)

Cook played a leading role in the strike that broke out at the Cambrian Combine, where its miners wanted parity with colliers working richer seams. Keir Hardie and Tom Mann arrived in the area to give the strikers their support. On the 8th November, strikers became involved in hand-to-hand fighting with the Glamorgan Constabulary. The home secretary, Winston Churchill, responded by sending in the British Army to "defend the mine-owners property". Hardie responded by claiming that "the bringing in of troops as typical of the militarism of the so-called Liberal reformers". (5)

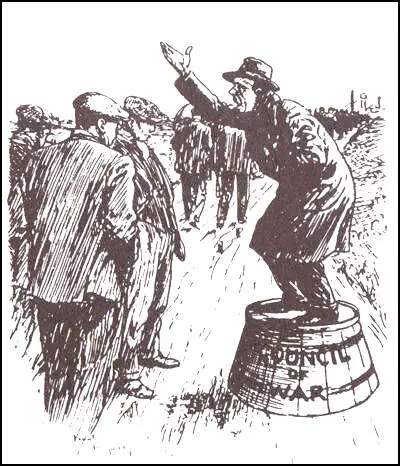

According to Christopher Farman, Cook was: "A wild but hypnotic orator, whose revolutionary fervour was flavoured with the religious revivalism of his days as a Baptist lay preacher, his pithead meetings drew crowds even greater than those which had listened to Keir Hardie. Cook was a mirror-image of every miner's frustrations and yearnings. In private conversation often in tears himself when describing the privations of the miners, Cook was able to produce an astonishing effect on an audience." (6)

Cook was awarded a two-year scholarship by the Pontypridd and Rhondda district of the South Wales Miners' Federation (SWMF) to the Central Labour College (CLC) in 1911. At the college he was deeply influenced by the ideas of Karl Marx. He did not return for his second year, instead becoming actively involved once more in the labour movement. He also helped establish the Industrial Democracy League and agitated for independent working-class education. (7)

Syndicalism

Cook became a supporter of a new political creed called syndicalism. Cook argued "that the power of the workers to organise or disrupt their own production – their power to strike – was the only power which the owners were likely to recognise: the only power which might change the miners’ conditions and the only power which could eventually change society". This was in direct opposition to the Labour Party that advocated a parliamentary approach to socialism. (8)

Arthur J. Cook joined forces with two other syndicalists, Noah Ablett and William H. Mainwaring, to produce the pamphlet, The Miners' Next Step (1912). It stated: "That the organisation shall engage in political action, both local and national, on the basis of complete independence of, and hostility to all capitalist parties, with an avowed policy of wresting whatever advantage it can for the working class... Today the shareholders own and rule the coalfields. They own and rule them mainly through paid officials. The men who work in the mine are surely as competent to elect these, as shareholders who may never have seen a colliery. To have a vote in determining who shall be your fireman, manager, inspector, etc., is to have a vote in determining the conditions which shall rule your working life. On that vote will depend in a large measure your safety of life and limb, of your freedom from oppression by petty bosses, and would give you an intelligent interest in, and control over your conditions of work. To vote for a man to represent you in Parliament, to make rules for, and assist in appointing officials to rule you, is a different proposition altogether." (9)

First World War

In the autumn of 1913 Cook had written articles for the South Wales Worker in which he criticised newspapers like the Daily Mail for building-up hatred of Germany. In August 1914 Cook was sacked and was given fourteen days' notice to quit the company house he rented. This was seen as blatant victimisation by the local union lodges and demanded the company reinstate him. The management refused and so the union threatened strike action. Worried about the impact of the strike on their profits that gave Cook his job back. (10)

After the outbreak of the First World War was active in the opposition to the conflict. He was especially angry about the willingness of the government to spend such large sums on the military where they had been slow to deal with the problems of working-class poverty. In one article for the Porth Gazette, he argued "we must do our duty as trade unionists and as citizens to force the Government, who in one night could vote £100 millions for destruction of human life to see that justice is meted out to these unfortunates". (11)

In March 1915 the Miners' Federation of Great Britain (MFGB) demanded a twenty per cent wage increase to compensate for inflation. The coalowners refused to discuss a national wage rise, and negotiations reverted to the districts. Agreements were arrived at satisfactorily in most areas, but in South Wales the owners were only willing to offer ten per cent. In July the miners in South Wales went on strike. (12)

Walter Runciman, the President of the Board of Trade, met with miners leaders but was unable to obtain an agreement. H. H. Asquith, considered using the Munitions of War Act, which effectively made strike action illegal. David Lloyd George warned against this and he negotiated a settlement that quickly conceded nearly all of the miners demands. This included a 18½ per cent wage increase. (13)

Cook was a strong opponent of conscription and advised union members not to volunteer for the armed forces: "Daily I see signs amongst the working class with whom I move and work of a mighty awakening. The chloroforming pill of patriotism is failing in its power to drug the mind and consciousness of the worker. He is beginning to shudder at his stupidity in allowing himself to become a party to such a catastrophe as we see today. The chains of slavery are being welded tighter upon us than ever. The ruling classes are over-reaching themselves in their hurry to enslave us... Economic conditions are forcing the workers to think; the scales are falling from their eyes. Men are wanted to give a lead. Comrades I appeal to you to rouse your union to protect the liberties of its members". (14)

The high casualty-rate during 1916, especially at the Somme Offensive, prompted the government to draft men from essential industries who had hitherto been exempt from conscription. It was decided to take 20,000 miners from the pits and put them in the army. Cook took steps to obstruct the military's attempts to recruit men and posted notices at the local colleries advising miners to disobey instructions to report for army examination. Captain Lionel Lindsay, Chief Constable of Glamorgan applied to the Home Office to have him prosecuted but worried it would result in a strike the suggestion was turned down. (15)

At a mass meeting on 15th April 1917, Cook called for "peace by negotiations". In an article in The Merthyr Pioneer, he argued: "I am no pacifist when war is necessary to free my class from the enslavement of capitalism... As a worker I have more regard for the interests of my class than any nation. The interests of my class are not benefited by this war, hence my opposition. Comrades, let us take heart, there are thousands of miners in Wales who are prepared to fight for their class. War against war must be the workers' cry." (16)

Arthur J. Cook welcomed the Russian Revolution and according to a MI5 agent he told one meeting: "To hell with everybody bar my class. To me, the hand of the German and Austrian is the same as the hand of my fellow-workmen at home. I am an internationalist. Russia has taken the step, and it is due to Britain to second the same and secure peace and leave the war and its cost to the capitalist who made it for the profiteer." (17)

In November, 1917, the Chief Constable of Glamorgan once again reported the activities of Cook to the Home Office: "It was only reported to me by a Recruiting Officer last night that A. J. Cook, the agitator from the Lewis-Merthyr Colliery, Trehafod, Glamorgan, who I have frequently reported for disloyal utterances, without success, openly declared, whilst denouncing the Recruiting Authorities at Pontypridd, that if he decided that a man should not join the Army the Military Authorities would not dare to send him... Anyone with the slightest knowledge of human nature must be well aware that to punish a conceited upstart of this type, especially when he is a man of no real influence, like Cook, always gives universal satisfaction." (18)

Cook continued to make speeches against the war. When he visited the village of Ynyshir he called on miners to do what they could to bring the war to an end: "Are we going to allow this war to go on? The government wants a hundred thousand men. They demand fifty thousand immediately, and the Clyde workers would not allow the government to take them. Let us stand by them, and show them that Wales will do the same. I have two brothers in the army who were forced to join, but I say No! I will be shot before I go to fight. Are you going to allow us to be taken to the war? If so, I say there will not be a ton of coal for the navy." (19)

Once again Captain Lionel Lindsay contacted the Home Office: "As promised I enclose a list of the ILP and advanced Syndicalists employed at our collieries, who are really the cause of a good deal of the trouble in this part of the coalfield, not only at our own collieries, but also in the neighbourhood. Of this lot, Cook is by far the most dangerous. As he considers himself an orator he has most to say at the various meetings in the district, and without exception, the policy which he preaches is the down-tool policy, and he is also concerned with the peace-cranks." (20)

In March 1918 the Home Office acceded to Lindsay's pressure and Cook as arrested and charged with sedition, Charged under the Defence of the Realm Act and was found guilty "of making statements likely to cause disaffection to His Majesty among the civilian population" and was sentenced to three months' imprisonment. Miners in the Rhondda threatened strike action and Cook was released after serving only two months. (21)

General Secretary of the MFGB

After his release from prison, he became increasingly seen as a leader of the left in the Rhondda. In November, 1919, he was elected as miners' agent for the area. On 31st July, 1920, he became a founder member of the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB). However, he resigned from the party a few months later over disagreement over industrial policy and rejoined the Independent Labour Party (ILP).

In January 1921 his meteoric rise continued when he became a member of the executive of the Miners' Federation of Great Britain (MFGB). "A month later the decontrol of the mining industry was announced, with a consequent end to a national wages agreement and wage reductions. A three-month lock-out from April 1921 ended in defeat for the miners; at its end Cook was again gaoled for two months' hard labour for incitement and unlawful assembly". (22)

Will Paynter, later recorded: "Cook had been a union leader at the colliery next down the valley to where I worked and we heard much of his exploits there as a fighter for wages and particularly for pit safety... He was... a master of his craft on the platform. I attended many of his meetings when he came to the Rhondda and he was undoubtedly a great orator, and had terrific support throughout the coalfields." (23) During this period he developed a reputation as a great orator. John Sankey, a High Court Judge, once stood at the back of a crowded miners' meeting to hear Cook speak. "Within fifteen minutes half the audience was in tears and Sankey admitted to having the greatest difficulty in restraining himself from weeping." (24)

In 1924 Harry Pollitt was appointed General Secretary of the National Minority Movement, a Communist-led united front within the trade unions. Pollitt worked alongside Tom Mann and according to one document the plan was "not to organize independent revolutionary trade unions, or to split revolutionary elements away from existing organizations affiliated to the T.U.C. but to convert the revolutionary minority within each industry into a revolutionary majority." Cook and a large number of miners also joined this organisation. (25)

Newspapers became increasingly concerned about the political activities of Cook. The Daily Mail reported that at a Labour Party meeting he claimed that people such as Jimmy Thomas and Tom Shaw "had no political class consciousness, and that the Labour leaders and trade union leaders were square pegs in round holes. He was glad to find some Red Socialists in London. He hoped he would find more later". The newspaper quoted Cook as saying: "I believe solely and absolutely in Communism. If there is no place for the Communists in the Labour Party, there is no place for the Right Wingers. I believe in strikes. They are the only weapon". (26)

Cook and Herbert Smith, the president of the MFGB, found it difficult to work together. Margaret Morris has argued that "Smith was temperamentally and politically the antithesis of Cook. Where Cook was emotional and voluble, Smith was dour and short of words. He was an old-style union leader, used to dominating the miners in Yorkshire... Relations between Smith and Cook were not always harmonious; neither of them really trusted the other's judgement, but each could respect that the other was dedicated to serving the miners. Neither of them was a very good negotiator: Cook was too excitable, and Smith perhaps a little too defensive in his tactics." (27)

Frank Hodges, general secretary of the Miners' Federation of Great Britain (MFGB) was elected for Litchfield in the 1923 General Election. Under the rules of the union he now had to resign his post but he initially refused. It was not until he was appointed as Civil Lord of the Admiralty in the Labour Government that he agreed to go. However, his time in Parliament did not last long and he was defeated in the 1924 General Election. (28)

Arthur Cook went on to secure the official South Wales nomination and subsequently won the national ballot by 217,664 votes to 202,297. Fred Bramley, general secretary of the TUC, was appalled at Cook's election. He commented to his assistant, Walter Citrine: "Have you seen who has been elected secretary of the Miners' Federation? Cook, a raving, tearing Communist. Now the miners are in for a bad time." However, his victory was welcomed by Arthur Horner who argued that Cook represented “a time for new ideas - an agitator, a man with a sense of adventure”. (29)

Red Friday

On 30th June 1925 the mine-owners announced that they intended to reduce the miner's wages. Will Paynter later commented: "The coal owners gave notice of their intention to end the wage agreement then operating, bad though it was, and proposed further wage reductions, the abolition of the minimum wage principle, shorter hours and a reversion to district agreements from the then existing national agreements. This was, without question, a monstrous package attack, and was seen as a further attempt to lower the position not only of miners but of all industrial workers." (30)

On 23rd July, 1925, Ernest Bevin, the general secretary of the Transport & General Workers Union (TGWU), moved a resolution at a conference of transport workers pledging full support to the miners and full co-operation with the General Council in carrying out any measures they might decide to take. A few days later the railway unions also pledged their support and set up a joint committee with the transport workers to prepare for the embargo on the movement of coal which the General Council had ordered in the event of a lock-out." (31) It has been claimed that the railwaymen believed "that a successful attack on the miners would be followed by another on them." (32)

In an attempt to avoid a General Strike, the prime minister, Stanley Baldwin, invited the leaders of the miners and the mine owners to Downing Street on 29th July. The miners kept firm on what became their slogan: "Not a minute on the day, not a penny off the pay". Herbert Smith, the president of the National Union of Mineworkers, told Baldwin: "We have now to give". Baldwin insisted there would be no subsidy: "All the workers of this country have got to take reductions in wages to help put industry on its feet." (33)

The following day the General Council of the Trade Union Congress triggered a national embargo on coal movements. On 31st July, the government capitulated. It announced an inquiry into the scope and methods of reorganization of the industry, and Baldwin offered a subsidy that would meet the difference between the owners' and the miners' positions on pay until the new Commission reported. The subsidy would end on 1st May 1926. Until then, the lockout notices and the strike were suspended. This event became known as Red Friday because it was seen as a victory for working class solidarity. (34)

Samuel Royal Commission

The Royal Commission was established under the chairmanship of Sir Herbert Samuel, to look into the problems of the Mining Industry. The commissioners took evidence from nearly eighty witnesses from both sides of the industry. They also received a great mass of written evidence, and visited twenty-five mines in various parts of Great Britain. The Samuel Commission published its report on 10th March 1926. Interest in it was so great that it sold over 100,000 copies. (35)

The Samuel Report was critical of the mine owners: "We cannot agree with the view presented to us by the mine owners that little can be done to improve the organization of the industry, and that the only practical course is to lengthen hours and to lower wages. In our view huge changes are necessary in other directions, and the large progress is possible". The report recognised that the industry needed to be reorganised but rejected the suggestion of nationalization. However, the report also recommended that the Government subsidy should be withdrawn and the miners' wages should be reduced. (36)

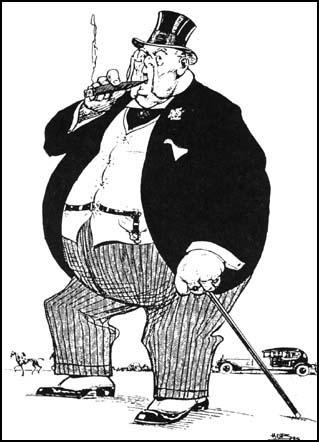

Trade Union Unity Magazine (1925)

The National Union of Mineworkers was put in a difficult position when Jimmy Thomas, the general secretary of the National Union of Railwaymen (NUR), welcomed the Samuel Report as a "wonderful document". Arthur J. Cook, at the MFGB conference advised delegates not to reject the report outright, so as not to jeopardise the support of the TUC. He was aware of the need to appear reasonable, but he also reaffirmed his opposition to wage reductions: "I am of the opinion we have got the biggest fight of our lives in front of us, but we cannot fight alone." (37)

Cook toured the mining areas in an attempt to gain support for the proposed strike. It is claimed that he made as many as six speeches a day in an attempt to keep up the spirits of the miners. One former miner remembered: "Never were such vast crowds seen in the coalfields – perhaps never in Britain – as that which the Miners’ General Secretary, Mr. A.J. Cook addressed... He got, and held, the crowds. It was unusual to have a miners’ official going through the coalfields in this way... That Mr. Cook was a subject of great devotion was undeniable. He was a prophet among them. To this day men speak of those gatherings with awe." (38) John Scanlon pointed out that "when Mr Cook addressed meetings, he did not hold the lapels of his jacket as all good statesmen do. Mr Cook took his jacket off." (39)

Arthur Horner later recalled: "We spoke together at meetings all over the country. We had audiences, mostly of miners, running into thousands. Usually I was put on first. I would make a good, logical speech, and the audience would listen quietly, but without any wild enthusiasm. Then Cook would take the platform. Often he was tired, hoarse and sometimes almost inarticulate. But he would electrify the meeting. They would applaud and nod their heads in agreement when he said the most obvious things. For a long time I was puzzled, and then one night I realised why it was. I was speaking to the meeting. Cook was speaking for the meeting. He was expressing the thoughts of his audience, I was trying to persuade them. He was the burning expression of their anger at the iniquities which they were suffering." (40)

Kingsley Martin, a journalist with the Manchester Guardian, was a supporter of the miners but was not convinced that Cook was the best person to negotiate an end to the dispute: "Cook made a most interesting study - worn-out, strung on wires, carried in the rush of the tidal wave, afraid of the struggle, afraid, above all, though, of betraying his cause and showing signs of weakness. He'll break down for certain, but I fear not in time. He's not big enough, and in an awful muddle about everything. Poor devil and poor England. A man more unable to conduct a negotiation I never saw. Many Trade Union leaders are letting the men down; he won't, but he'll lose. And Socialism in England will be right back again." (41)

Beatrice Webb, one of the leaders of the Fabian Society, was also highly critical of Cook: "He is a loosely built ugly-featured man - looks low-caste - not at all the skilled artisan type, more the agricultural labourer. He is oddly remarkable in appearance because of his excitability of gesture, mobility of expression in his large-lipped mouth, glittering china-blue eyes, set close together in a narrow head with lanky yellow hair - altogether a man you watch with a certain admiring curiosity ... it is clear that he has no intellect and not much intelligence - he is a quivering mass of emotions, a mediumistic magnetic sort of creature - not without personal attractiveness - an inspired idiot, drunk with his own words, dominated by his own slogans. I doubt whether he even knows what he is going to say or what he has just said." (42)

David Kirkwood, took a different view of the general secretary of the MFGB: "The purpose of the General Strike was to obtain justice for the miners. The method was to hold the Government and the nation up to ransom. We hoped to prove that the nation could not get on without the workers. We believed that the people were behind us. We knew that the country had been stirred by our campaign on behalf of the miners. Arthur Cook, who talked from a platform like a Salvation Army preacher, had swept over the industrial districts like a hurricane. He was an agitator, pure and simple. He had no ideas about legislation or administration. He was a flame. Ramsay MacDonald called him a guttersnipe. That he certainly was not. He was utterly sincere, in deadly earnest, and burnt himself out in the agitation." (43)

The Daily Mail Strike

Stanley Baldwin and his ministers had several meetings with both sides in order to avoid the strike. Thomas Jones, the Deputy Secretary to the Cabinet, pointed out: "It is possible not to feel the contrast between the reception which Ministers give to a body of owners and a body of miners. Ministers are at ease at once with the former, they are friends jointly exploring a situation. There was hardly any indication of opposition or censure. It was rather a joint discussion of whether it was better to precipitate a strike or the unemployment which would result from continuing the present terms. The majority clearly wanted a strike." (44)

Considering themselves in a position of strength, the Mining Association now issued new terms of employment. These new procedures included an extension of the seven-hour working day, district wage-agreements, and a reduction in the wages of all miners. Depending on a variety of factors, the wages would be cut by between 10% and 25%. The mine-owners announced that if the miners did not accept their new terms of employment then from the first day of May they would be locked out of the pits. (45)

At the end of April 1926, the miners were locked out of the pits. A Conference of Trade Union Congress met on 1st May 1926, and afterwards announced that a General Strike "in defence of miners' wages and hours" was to begin two days later. The leaders of the Trade Union Council were unhappy about the proposed General Strike, and during the next two days frantic efforts were made to reach an agreement with the Conservative Government and the mine-owners. (46)

Ramsay MacDonald, the leader of the Labour Party refused to support the General Strike. MacDonald argued that strikes should not be used as a political weapon and that the best way to obtain social reform was through parliamentary elections. He was especially critical of Cook. He wrote in his diary: "It really looks tonight as though there was to be a General Strike to save Mr. Cook's face... The election of this fool as miners' secretary looks as though it would be the most calamitous thing that ever happened to the T.U. movement." (47)

The Trade Union Congress called the General Strike on the understanding that they would then take over the negotiations from the Miners' Federation. The main figure involved in an attempt to get an agreement was Jimmy Thomas. Talks went on until late on Sunday night, and according to Thomas, they were close to a successful deal when Stanley Baldwin broke off negotiations as a result of a dispute at the Daily Mail. (48)

What had happened was that Thomas Marlowe, the editor the newspaper, had produced a provocative leading article, headed "For King and Country", which denounced the trade union movement as disloyal and unpatriotic.The workers in the machine room, had asked for the article to be changed, when he refused they stopped working. Although, George Isaacs, the union shop steward, tried to persuade the men to return to work, Marlowe took the opportunity to phone Baldwin about the situation. (49)

The strike was unofficial and the TUC negotiators apologized for the printers' behaviour, but Baldwin refused to continue with the talks. "It is a direct challenge, and we cannot go on. I am grateful to you for all you have done, but these negotiations cannot continue. This is the end... The hotheads had succeeded in making it impossible for the more moderate people to proceed to try to reach an agreement." A letter was handed to the TUC negotiators that stated that the "gross interference with the freedom of the press" involved a "challenge to the constitutional rights and freedom of the nation". (50)

The General Strike

The General Strike began on 3rd May, 1926. The Trade Union Congress adopted the following plan of action. To begin with they would bring out workers in the key industries - railwaymen, transport workers, dockers, printers, builders, iron and steel workers - a total of 3 million men (a fifth of the adult male population). Only later would other trade unionists, like the engineers and shipyard workers, be called out on strike. Ernest Bevin, the general secretary of the Transport & General Workers Union (TGWU), was placed in charge of organising the strike. (51)

The TUC decided to publish its own newspaper, The British Worker, during the strike. Some trade unionists had doubts about the wisdom of not allowing the printing of newspapers. Workers on the Manchester Guardian sent a plea to the TUC asking that all "sane" newspapers be allowed to be printed. However, the TUC thought it would be impossible to discriminate along such lines. Permission to publish was sought by George Lansbury for Lansbury's Labour Weekly and H. N. Brailsford for the New Leader. The TUC owned Daily Herald also applied for permission to publish. Although all these papers could be relied upon to support the trade union case, permission was refused. (52)

The government reacted by publishing The British Gazette. Baldwin gave permission to Winston Churchill to take control of this venture and his first act was commandeer the offices and presses of The Morning Post, a right-wing newspaper. The company's workers refused to cooperate and non-union staff had to be employed. Baldwin told a friend that he gave Churchill the job because "it will keep him busy, stop him doing worse things". He added he feared that Churchill would turn his supporters "into an army of Bolsheviks". (53)

The government relied on volunteers to do the work of the strikers. Cass Canfield, worked in publishing until the strike began. "The British General Strike, which occurred in 1926, completely tied up the nation until the white-collar class went to work and restored some of the services. I remember watching gentlemen with Eton ties acting as porters in Waterloo Station; other volunteers drove railroad engines and ran buses. I was assigned to delivering newspapers and would report daily, before dawn, at the Horse Guards Parade in London. As time passed, the situation worsened; barbed wire appeared in Hyde Park, and big guns. Winston Churchill went down to the docks in an attempt to quell the rioting. For a couple of days there were no newspapers, and that was hardest of all to bear for no one knew what was going to happen next and everyone feared the outbreak of widespread violence. Finally, a single-sheet government handout appeared - the British Gazette - and people breathed easier, but settlement of the issues dividing labor and the government appeared to be insoluble." (54)

However, most members of the Labour Party supported the strikers. This included Margaret Cole, who worked for the Fabian Research Department, pointed out: "Some members of the Labour Club formed a University Strike Committee, which set itself three main jobs; to act as liaison between Oxford and Eccleston Square, then the headquarters of the TUC and the Labour Party, to get out strike bulletins and propaganda leaflets for the local committees, and to spread them and knowledge of the issues through the University and the nearby villages." (55)

The Media and the General Strike

In his book on the the General Strike, the historian Christopher Farman, studied the way the media dealt with this important industrial dispute. John C. Davidson, the Chairman of the Conservative Party, was given responsibility for the way the media should report the strike. "As soon as it became evident that newspaper production would be affected by the strike, Davidson arranged to bring the British Broadcasting Company under his effective control... no news was broadcast during the crisis until it had first been personality vetted by Davidson... Each of the five daily news bulletins plus a daily 'appreciation of the situation', which took the place of newspaper editorials, were drafted by Gladstone Murray in conjunction with Munro and then submitted to Davidson for his approval before being transmitted from the BBC's London station at Savoy Hill." (56)

As part of the government propaganda campaign, the BBC reported that public transport was functioning again and after the first week of the strike it announced that most railmen had returned to work. This was in fact untrue as 97% of National Union of Railwaymen members remained on strike. It was true that volunteers were emerging from training and that more trains were in service. However, there was a sharp increase in accidents and several passengers were killed during the strike. Unskilled volunteers were also accused of causing thousands of pounds' worth of damage. (57)

Several politicians representing the Conservative Party and the Liberal Party, appeared on BBC radio and made vicious attacks on the trade union movement. William Graham, the Labour Party MP for Edinburgh Central, wrote to John Reith, the BBC's managing director, suggesting that he should allow "a representative Labour or Trade Union leader to state the case for the miners and other workers in this crisis". (58)

Ramsay MacDonald, the leader of the Labour Party, also contacted Reith and asked for permission to broadcast his views. Reith recorded in his diary: "He (MacDonald) said he was anxious to give a talk. He sent a manuscript along... with a friendly note offering to make any alterations which I wanted... I sent it at once to Davidson for him to ask the Prime Minister, strongly recommending that he should allow it to be done." The idea was rejected and Reith argued: "I do not think that they treat me altogether fairly. They will not say we are to a certain extent controlled and they make me take the onus of turning people down. They are quite against MacDonald broadcasting, but I am certain it would have done no harm to the Government. Of course it puts me in a very awkward and unfair position. I imagine it comes chiefly from the PM's difficulties with the Winston lot." (59)

When he heard the news, MacDonald, wrote Reith an angry letter, calling "for an opportunity for the fair-minded and reasonable public to hear Labour's point of view". Anne Perkins, the author of A Very British Strike: 3 May-12 May 1926 (2007) has argued that if the government had accepted the proposal and people had "heard an Opposition voice would certainly have done something to restore the faith of millions of working-class people who had lost confidence in the BBC's potential to be a national institution and a reliable and trustworthy source of news." (60)

At the same time Stanley Baldwin was allowed to make several broadcasts on the BBC. Baldwin "had recognized the importance of the new medium from its inception... now, with an expert blend of friendliness and firmness, he repeated that the strike had first to be called off before negotiations could resume, but repudiated the suggestion that the Government was fighting to lower the standard of living of the miners or of any other section of the workers". (61)

In one broadcast Baldwin argued: "A solution is within the grasp of the nation the instant that the trade union leaders are willing to abandon the General Strike. I am a man of peace. I am longing and working for peace, but I will not surrender the safety and security of the British Constitution. You placed me in power eighteen months ago by the largest majority accorded to any party for many years. Have I done anything to forfeit that confidence? Cannot you trust me to ensure a square deal, to secure even justice between man and man?" (62)

By 12th May, 1926, most of the daily newspapers had resumed publication. The Daily Express reported that the "strike had a broken back" and it would be all over by the end of the week. (63) Harold Harmsworth, Lord Rothermere, was extremely hostile to the strike and all his newspapers reflected this view. The Daily Mirror stated that the "workers have been led to take part in this attempt to stab the nation in the back by a subtle appeal to the motives of idealism in them." (64) The Daily Mail claimed that the strike was one of "the worst forms of human tyranny". (65)

Negotiations with the TUC

Walter Citrine, the general secretary of the Trade Union Congress (TUC), was desperate to bring an end to the General Strike. He argued that it was important to reopen negotiations with the government. His view was "the logical thing is to make the best conditions while our members are solid". Baldwin refused to talk to the TUC while the General Strike persisted. Citrine therefore contacted Jimmy Thomas, the general secretary of the National Union of Railwaymen (NUR), who shared this view of the strike, and asked him to arrange a meeting with Herbert Samuel, the Chairman of the Royal Commission on the Coal Industry. (66)

Without telling the miners, the TUC negotiating committee met Samuel on 7th May and they worked out a set of proposals to end the General Strike. These included: (i) a National Wages Board with an independent chairman; (ii) a minimum wage for all colliery workers; (iii) workers displaced by pit closures to be given alternative employment; (iv) the wages subsidy to be renewed while negotiations continued. However, Samuel warned that subsequent negotiations would probably mean a reduction in wages. These terms were accepted by the TUC negotiating committee, but were rejected by the executive of the Miners' Federation. (67)

Citrine wrote in his diary: "Miner after miner got up and, speaking with intensity of feeling, affirmed that the miners could not go back to work on a reduction in wages. Was all this sacrifice to be in vain?" Citrine quoted Cook as saying: "Gentleman, I know the sacrifice you have made. You do not want to bring the miners down. Gentlemen, don't do it. You want your recommendations to be a common policy with us, but that is a hard thing to do." (68)

On the 11th May, at a meeting of the Trade Union Congress General Committee, it was decided to accept the terms proposed by Herbert Samuel and to call off the General Strike. The following day, the TUC General Council visited 10 Downing Street and the TUC attempted to persuade the Government to support the Samuel proposals and to offer a guarantee that there would be no victimization of strikers.

Baldwin refused but did say if the miners returned to work on the current conditions he would provide a subsidy for six weeks and then there would be the pay cuts that the Mine Owners Association wanted to impose. He did say that he would legislate for the amalgamation of pits, introduce a welfare levy on profits and introduce a national wages board. The TUC negotiators agreed to this deal. As Lord Birkenhead, a member of the Government was to write later, the TUC's surrender was "so humiliating that some instinctive breeding made one unwilling even to look at them." (69)

Baldwin already knew that the Mine Owners Association would not agree to the proposed legislation. They had already told Baldwin that he must not meddle in the coal industry. It would be "impossible to continue the conduct of the industry under private enterprise unless it is accorded the same freedom from political interference that is enjoyed by other industries." (70)

To many trade unionists, Walter Citrine had betrayed the miners. A major factor in this was money. Strike pay was haemorrhaging union funds. Information had been leaked to the TUC leaders that there were cabinet plans originating with Winston Churchill to introduce two potentially devastating pieces of legislation. "The first would stop all trade union funds immediately. The second would outlaw sympathy strikes. These proposals would... make it impossible for the trade unions' own legally held and legally raised funds to be used for strike pay, a powerful weapon to drive trade unionists back to work." (71)

Seven Month Lockout

Arthur Pugh, the President of the Trade Union Congress, and Jimmy Thomas, the general secretary of the National Union of Railwaymen (NUR), informed the Miners' Federation of Great Britain leaders, that if the General Strike was terminated the government would instruct the owners to withdraw their notices, allowing the miners to return to work on the "status quo" while the wage reductions and reorganisation machinery were negotiated. Arthur J. Cook asked what guarantees the TUC had that the government would introduce the promised legislation, Thomas replied: "You may not trust my word, but will not accept the word of a British gentleman who has been Governor of Palestine". (72)

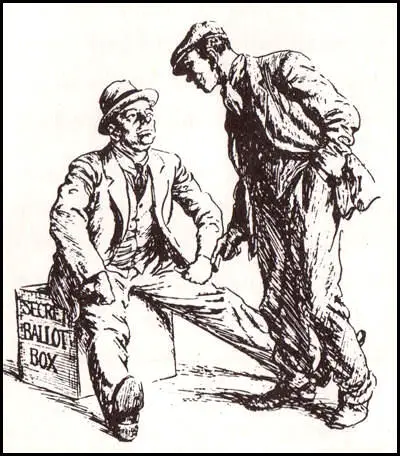

Bernard Partridge, Secret Ballot (13th October 1926)

Jennie Lee, was a student at Edinburgh University when her father, a miner in Lochgelly in Scotland. During the lock-out she returned to help her family. "Until the June examinations were over I was chained to my books, but I worked with a darkness around me. What was happening in the coalfield? How were they managing? Once I was free to go home to Lochgelly my spirits rose. When you are in the thick of a fight there is a certain exhilaration that keeps you going." (73)

When the General Strike was terminated, the miners were left to fight alone. Cook appealed to the public to support them in the struggle against the Mine Owners Association: "We still continue, believing that the whole rank and file will help us all they can. We appeal for financial help wherever possible, and that comrades will still refuse to handle coal so that we may yet secure victory for the miners' wives and children who will live to thank the rank and file of the unions of Great Britain." (74)

Newspapers relentlessly attacked Cook during the lock-out: "The press had hated Cook ever since he was first elected. Now, in the full flow of the lock-out, they brought out all the tricks of the trade to damage him... By use of demonology - the study of the devil - they sought to detach the miners’ leader from the miners. All Cook’s qualities were described as characteristics of the devil. His passionate oratory became demagogy; his unswerving principles became fanaticism; his short, stooping stature became the deformity of some gnome or imp. In particular, Cook’s independence of mind and thought was turned into its opposite. He was the tool of others, the plaything of a foreign power". (75)

The Morning Post reported a speech made by Sir Henry Page Croft, a right-wing Conservative Party MP who had been issuing favourable statements about Italy's new leader, Benito Mussolini. "I want to warn you most seriously that the government of Russia is making war on this country daily... Mr Cook (cries of ‘Shoot Him!’, ‘Lynch Him!’) has declared that he is a Bolshevik and is proud to be a humble disciple of Lenin. He is treating the miners of this country whom we all respect and honour as cannon fodder in order to achieve his vainglorious ambitions." (76)

Despite these attacks Cook remained the support of most of his members. A miner's wife was quoted as saying: "Cook is trusted implicitly. The malicious attacks of the capitalist Press only serve to strengthen the loyalty the miners and their wives feel for him.". (77) Ellen Wilkinson, a young left-wing Labour MP, wrote: "In thousands of homes all over the country, and particularly miners’ homes, there is hanging today, in the place of honour, the picture of A.J. Cook. He is without a shadow of a doubt the hero of the working women." (78)

when you can starve for mine" (13th October 1926)

On 21st June 1926, the British Government introduced a Bill into the House of Commons that suspended the miners' Seven Hours Act for five years - thus permitting a return to an 8 hour day for miners. In July the mine-owners announced new terms of employment for miners based on the 8 hour day. As Anne Perkins has pointed out this move "destroyed any notion of an impartial government". (79)

Cook toured the coalfields making passionate speeches in order to keep the strike going: "I put my faith to the women of these coalfields. I cannot pay them too high a tribute. They are canvassing from door to door in the villages where some of the men had signed on. The police take the blacklegs to the pits, but the women bring them home. The women shame these men out of scabbing. The women of Notts and Derby have broken the coal owners. Every worker owes them a debt of fraternal gratitude." (80)

Hardship forced men to begin to drift back to the mines. By the end of August, 80,000 miners were back, an estimated ten per cent of the workforce. 60,000 of those men were in two areas, Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire. "Cook set up a special headquarters there and rushed from meeting to meeting. He was like a beaver desperately trying to dam the flood. When he spoke, in, say, Hucknall, thousands of miners who had gone back to work would openly pledge to rejoin the strike. They would do so, perhaps for two or three days, and then, bowed down by shame and hunger, would drift back to work." (81)

Herbert Smith and Arthur Cook had a meeting with government representatives on 26th August, 1926. By this stage Cook was willing to do a deal with the government than Smith. Cook asked Winston Churchill: "Do you agree that an honourably negotiated settlement is far better than a termination of struggle by victory or defeat by one side? Is there no hope that now even at this stage the government could get the two sides together so that we could negotiate a national agreement and see first whether there are not some points of agreement rather than getting right up against our disagreements." (82) According to Beatrice Webb "if it were not for the mule-like obstinacy of Herbert Smith, A. J. Cook would settle on any terms." (83)

This meeting revealed the differences between Smith and Cook. "After a wary start the two seem to have developed a mutual respect during their many hours of shared stress. By the middle of the lock-out, however, they seem to have drifted on to different. wavelengths. Undoubtedly Cook felt Smith's obstinacy to be impractical and damaging. Smith, however, as MFGB President, was the Federation's chief spokesman, and Cook could not officially or openly dissociate himself from Smith's position. The MFGB special conference had granted the officials unfettered negotiating power, but Smith seems to have grown more stubborn as the miners' bargaining position worsened. One may admire his spirit, but not his wisdom. It is likely that by this time Smith reflected a minority view within the Federation Executive, but as President his position was unchallengeable, and there was no public dissent at his inflexibility. Cook, meanwhile, had embraced a conciliatory, face-saving position: he was only too aware of the drift back to work in some areas; he saw the deteriorating condition of many miners and their families." (84)

In October, 1926, G. D. H. Cole of the Labour Research Department, published The Coal Shortage: Why the Miners Will Win, with a foreword by Cook. It pointed out that the strike had a very damaging impact on the British economy. Pig iron production, which had averaged 538,000 tons a month from January to April, was down to 14,000 tons in August. Steel production, 697,000 tons a month from January to April, had slumped to 52,000 tons. The president of the Federation of British Industries, Sir Max Muspratt, had estimated the total cost of the strike to the beginning of October was £541 million. "By the end of the year the loss would amount to between £1,000 and £1,500 million." (85)

By the end of November 1926 most miners had reported back to work. Will Paynter remained loyal to the strike although he knew they had no chance of winning. "The miners' lock-out dragged on through the months of 1926 and really was petering-out when the decision came to end it. We had fought on alone but in the end we had to accept defeat spelt out in further wage-cuts." (86)

The Aftermath

Cook remained defiant and argued on 28th November, 1926: "I declare publicly, with full knowledge of all that it means, that the Miners' Federation will leave no stone unturned to rebuild its forces, to remove the eight hour day, to establish one union for the miners of Great Britain, and a national agreement for the mining industry... We have lost ground, but we shall regain it in a very short time buy using both our industrial and political machines." (87)

As one historian pointed out: "Many miners found they had no jobs to return to as many coal-owners used the eight-hour day to reduce their labour force while maintaining productions levels. Victimisation was practised widely. Militants were often purged from payrolls. Blacklists were drawn up and circulated among employers; many energetic trade unionists never worked in a it again after 1926. Following months of existence on meague lockout payments and charity, many miners' families were sucked by unemployment, short-term working, debts and low wages into abject poverty." (88)

In December, 1926, Cook visited the Soviet Union and thanked officials for donations made during the General Strike.

Russian workers, he pointed out, contributed more to the strike fund than the combined contributions of unions affiliated to the TUC. At the end of the tour he commented: "I promise to devote all my powers to Lenin's doctrines and to the colossal work begun by him as his sincere and loving disciple. Long live the Soviets! Long Live the Revolution!... I return (to Britain) encouraged for the great class war... May the English revolution come soon." (89)

This statement increased the hostility of the press towards Cook. Leaders of the Labour Party also attacked Cook. Ramsay MacDonald claimed that "in all my experience of trade union leadership... I have never known one so incompetent." (90) Philip Snowden claimed that Cook had wrecked the Miners' Federation of Great Britain and "given the mineowners a power they have never before possessed, given the Conservative government an excuse for lengthening hours and making a general attack upon trade union rights, reduced practically every trade union to a state of bankruptcy and inflicted permanent injury upon British trade." (91)

In 1927 the British Government passed the Trade Disputes and Trade Union Act. This act made all sympathetic strikes illegal, ensured the trade union members had to voluntarily 'contract in' to pay the political levy to the Labour Party, forbade Civil Service unions to affiliate to the TUC, and made mass picketing illegal. As A. J. P. Taylor has pointed out: "The attack on Labour party finance came ill from the Conservative s who depended on secret donations from rich men." (92)

Miners' Federation of Great Britain saw a major drop in membership. "The union was lucky to survive at all. In many places, it didn’t. At Maerdy pit, in South Wales, the proud flagship of the Federation for a quarter of a century, the owners wreaked terrible revenge. They refused to recognise the union, and victimised anyone known to be a member. In 1927 there were 377 employed members of the lodge at Maerdy; in 1928, only eight... This was not because the overall unemployment figures were falling - quite the reverse. It was just that to stand any chance of getting work, men were forced to leave the union (or the area)." (93)

Despite its victory over the trade union movement, the public turned against Stanley Baldwin and his conservative government. Between 1926 and 1929 the Labour Party won all the thirteen by-elections that took place. Cook made his peace with the Labour leadership and in February, he attended a meeting with the Labour leaders in which he agreed a way forward. In a speech he made the following month he argued "I have fought for and will continue to fight for a Labour government as a step to socialism; to repeal the pernicious 8-hours Act; to secure a Minimum Wage, adequate pensions at 60, nationalisation of the mines, minerals and by-products. A Labour government would bring new life and hope to the workers; it would increase faith in trade unionism and would lead us nearer to socialism." (94)

In the 1929 General Election Labour won 287 seats and its leader, Ramsay MacDonald, formed the next government. However, it soon became clear that MacDonald was not willing to keep his promises. The Eight Hours Bill was not repealed, there were no provisions for adequate pensions at 60, a minimum wage for miners or any plans to nationalise the industry. "He saw very quickly that the Labour government was not bringing new life and hope to the workers. Instead, it brought more unemployment, more sickness and more despair. He noticed that in two years the government had decreased faith in trade unionism and had postponed any socialism by as long as anyone could see into the future". (95)

He explained his disillusionment with Labour government in a letter to the prime minister. "I think you should know how some of us feel in regard to the action of the Labour Cabinet towards the mineworkers. I am terribly disappointed at the shabby way our men have been treated in the face of the attacks of the coal owners especially in South Wales. I think a Labour government would defend its own Mines Act and put up a fight against the coal owners attacking the mineworkers - but no - we are left to battle alone against the most vicious set of capitalists existing in this country. We have had nothing but lavish promises from a Labour government which makes it difficult and impossible for some of us to defend (it) in the future. It appears to me that our only hope is in our trade union movement. Had it not been for the splendid fight put up by the South Wales miners, huge reductions would have been forced upon them." (96)

Cook's health went into decline after the General Strike. Ignoring all advice he refused to reduce his workload, and continuously drove himself to the point of breakdown. His failure to seek medical attention for an injury to his leg that had been aggravated by a kick from a demonstrator, resulted in its amputation above the knee on 19th January 1931. One of his visitors in hospital was Oswald Mosley, the Labour Party MP for Smethwick, and was the only trade union leader who agreed to sign his manifesto that urged the government to provide old-age pensions at sixty, the raising of the school-leaving age and more public spending to cut unemployment, and a programme of public works. However, he refused to join his New Party. (97)

Within six weeks of his operation Cook was back at work equipped with a cork leg and crutches. However, in July he was diagnosed with cancer. In September he attended the Trade Union Congress in Bristol against doctor's orders, and there he told a reporter that he knew he was "for it". Later that month he had a cancerous growth from his neck. However, he also suffering from lung cancer. (98)

The 1931 General Election was held on 27th October, 1931. MacDonald led an anti-Labour alliance made up of Conservatives and National Liberals. It was a disaster for the Labour Party with only 46 members winning their seats. Several leading Labour figures, including Arthur Henderson, John R. Clynes, Arthur Greenwood, Charles Trevelyan, Herbert Morrison, Emanuel Shinwell, Frederick Pethick-Lawrence, Hugh Dalton, Susan Lawrence, William Wedgwood Benn, and Margaret Bondfield lost their seats.

Cook told Ben Tillett that he was very upset by the election result. "He (Arthur Cook) was terribly agitated about the Labour Party's collapse in the election, and said to me, What has happened to the multitude to desert you and other old friends like this? I tried to soothe him, and assured him that the cause was not dead, and would rise again. He grasped my hand and held it for about ten minutes, saying beseechingly, Don't go, old man. Don't leave me. Then he seemed to pause a little, and murmured, Goodbye, Ben. I left him then, knowing that the end was very near. (99)

Cook's condition remained critical for several days, and he finally died aged 47 on 2nd November, 1931. "Apparently his last words were to a nurse who was watching over him - it was a cold night, and he told her to go and warm herself; she returned to find him dead." (100)

Arthur James Cook was cremated at Golders Green. Ernest Bevin was one of those who paid tribute to him. "I know of no man in the Miners' Federation who had fought so hard and yet created such an extraordinary love for himself in the hearts of miners as Arthur Cook. He was abused probably more than any other man of his generation, and yet all the time he worked and fought, guided by the highest motives." (101)

Primary Sources

(1) Arthur J. Cook, Noah Ablett and Stephen Owen Davies, The Miners' Next Step (1912)

Today the shareholders own and rule the coalfields. They own and rule them mainly through paid officials. The men who work in the mine are surely as competent to elect these, as shareholders who may never have seen a colliery. To have a vote in determining who shall be your fireman, manager, inspector, etc., is to have a vote in determining the conditions which shall rule your working life. On that vote will depend in a large measure your safety of life and limb, of your freedom from oppression by petty bosses, and would give you an intelligent interest in, and control over your conditions of work. To vote for a man to represent you in Parliament, to make rules for, and assist in appointing officials to rule you, is a different proposition altogether.

Our objective begins to take shape before your eyes. Every industry thoroughly organized, in the first place, to fight, to gain control of, and then to administer, that industry. The co-ordination of all industries on a Central Production Board, who, with a statistical department to ascertain the needs of the people, will issue its demands on the different departments of industry, leaving to the men themselves to determine under what conditions and how, the work shall be done. This would mean real democracy in real life, making for real manhood and womanhood. Any other form of democracy is a delusion and a snare.

Every fight for, and victory won by the men, will inevitably assist them in arriving at a clearer conception of the responsibilities and duties before them. It will also assist them to see, that so long as Shareholders are permitted to continue their ownership, or the State administers on behalf of the Shareholders, slavery and oppression are bound to be the rule in industry. And with this realization, the age-long oppression of Labour will draw to its end. The weary sigh of the overdriven slave, pitilessly exploited and regarded as an animated tool or beast of burden: the mediaeval serf fast bound to the soil, and life-long prisoner on his lord's domain, subject to all the caprices of his lord's lust or anger: the modern wageslave, with nothing but his labour to sell, selling that, with his manhood as a wrapper, in the world's market place for a mess of pottage: these three phases of slavery, each in their turn inevitable and unavoidable, will have exhausted the possibilities of slavery, and mankind shall at last have leisure and inclination to really live as men, and not as the beasts which perish.

(2) Arthur J. Cook, The Merthyr Pioneer (15th April, 1916)

Daily I see signs amongst the working class with whom I move and work of a mighty awakening. The chloroforming pill of patriotism is failing in its power to drug the mind and consciousness of the worker. He is beginning to shudder at his stupidity in allowing himself to become a party to such a catastrophe as we see today. The chains of slavery are being welded tighter upon us than ever. The ruling classes are over-reaching themselves in their hurry to enslave us... Economic conditions are forcing the workers to think; the scales are falling from their eyes. Men are wanted to give a lead. Comrades I appeal to you to rouse your union to protect the liberties of its members. An industrial truce was entered into by our leaders behind our backs which had opened the way for any encroachment upon our rights and liberties. Away with the industrial truce! We must not stand by and allow the workers to be exploited and our liberties taken away.

(3) Arthur J. Cook, The Merthyr Pioneer (3rd March, 1917)

I am no pacifist when war is necessary to free my class from the enslavement of capitalism... As a worker I have more regard for the interests of my class than any nation. The interests of my class are not benefitted by this war, hence my opposition. Comrades, let us take heart, there are thousands of miners in Wales who are prepared to fight for their class. War against war must be the workers' cry.

(4) Captain Lionel Lindsay, Chief Constable of Glamorgan, report to the Home Office (24th November 1917)

It was only reported to me by a Recruiting Officer last night that A. J. Cook, the agitator from the Lewis-Merthyr Colliery, Trehafod, Glamorgan, who I have frequently reported for disloyal utterances, without success, openly declared, whilst denouncing the Recruiting Authorities at Pontypridd, that if he decided that a man should not join the Army the Military Authorities would not dare to send him... Anyone with the slightest knowledgee of human nature must be well aware that to punish a conceited upstart of this type, especially when he is a man of no real influence, like Cook, always gives universal satisfaction.

(5) Arthur J. Cook, speech in Ynyshir (20th January 1918)

Are we going to allow this war to go on? The government wants a hundred thousand men. They demand fifty thousand immediately, and the Clyde workers would not allow the government to take them. Let us stand by them, and show them that Wales will do the same. I have two brothers in the army who were forced to join, but I say "No!" I will be shot before I go to fight. Are you going to allow us to be taken to the war? If so, I say there will not be a ton of coal for the navy.

(6) Captain Lionel Lindsay, Chief Constable of Glamorgan, report to the Home Office (24th November 1917)

As promised I enclose a list of the ILP and advanced Syndicalists employed at our collieries, who are really the cause of a good deal of the trouble in this part of the coalfield, not only at our own collieries, but also in the neighbourhood. Of this lot, Cook is by far the most dangerous. As he considers himself an orator he has most to say at the various meetings in the district, and without exception, the policy which he preaches is the down-tool policy, and he is also concerned with the peace-cranks.

(7) Will Paynter, My Generation (1972)

The secretary of the miners' union was, at this time, A. J. Cook, an eloquent agitator, who coined the slogan around which all miners rallied: "Not a penny off the pay; not a minute on the day." Cook had been a union leader at the colliery next down the valley to where I worked and we heard much of his exploits there as a fighter for wages and particularly for pit safety. He later became a miners' agent for the Rhondda, and I remember discussing his work as an agent with the officials of the Cymmer lodge some years later, when I became a member of the committee. They supported his candidature for national secretary in 1924, but did not regard him as a good negotiator at pit level. He was, however, a master of his craft on the platform. I attended many of his meetings when he came to the Rhondda and he was undoubtedly a great orator, and had terrific support throughout the coalfields. He frequently said: "When you hear that A.J. has been dining with royalty, he will have deserted you." When he came back to Porth just after dining with the Prince of Wales, he was accused by the men at the meeting of having broken faith with them. These men were largely from the pit where he had previously worked and their accusations must have hurt him deeply.

(8) The Daily Mail (21st June 1924)

Mr A.J. Cook, the secretary of the Miners’ Federation, was the guest of a social evening held by the Holborn Labour Party at 16 Harpur Street, Theobalds Road, WC, last night. Mr Cook said that Mr J.H. Thomas and Mr Tom Shaw had no political class consciousness, and that the Labour leaders and trade union leaders were square pegs in round holes. He was glad to find some Red Socialists in London. He hoped he would find more later. Mr Cook added: “I believe solely and absolutely in Communism. If there is no place for the Communists in the Labour Party, there is no place for the Right Wingers. I believe in strikes. They are the only weapon”.

(9) Christopher Farman, The General Strike: Britain's Aborted Revolution? (1974)

A wild but hypnotic orator, whose revolutionary fervour was flavoured with the religious revivalism of his days as a Baptist lay preacher, his pithead meetings drew crowds even greater than those which had listened to Keir Hardie. Cook was a mirror-image of every miner's frustrations and yearnings. In private conversation often in tears himself when describing the privations of the miners, Cook was able to produce an astonishing effect on an audience. Lord Sankey, a High Court Judge who chaired the Royal Commission on the mining industry in 1919, once stood at the back of a crowded miners' meeting to hear Cook speak. Within fifteen minutes half the audience was in tears and Sankey admitted to having the greatest difficulty in restraining himself from weeping.

(10) Kingsley Martin, diary entry (26th April, 1926)

26th April, 1926: Cook made a most interesting study - worn-out, strung on wires, carried in the rush of the tidal wave, afraid of the struggle, afraid, above all, though, of betraying his cause and showing signs of weakness. He'll break down for certain, but I fear not in time. He's not big enough, and in an awful muddle about everything. Poor devil and poor England. A man more unable to conduct a negotiation I never saw. Many Trade Union leaders are letting the men down; he won't, but he'll lose. And Socialism in England will be right back again.

(11) Beatrice Webb, diary entry (10th September, 1926)

He is a loosely built ugly-featured man - looks low-caste - not at all the skilled artisan type, more the agricultural labourer. He is oddly remarkable in appearance because of his excitability of gesture, mobility of expression in his large-lipped mouth, glittering china-blue eyes, set close together in a narrow head with lanky yellow hair - altogether a man you watch with a certain admiring curiosity ... it is clear that he has no intellect and not much intelligence - he is a quivering mass of emotions, a mediumistic magnetic sort of creature - not without personal attractiveness - an inspired idiot, drunk with his own words, dominated by his own slogans. I doubt whether he even knows what he is going to say or what he has just said.

(12) Paul Foot, An Agitator of the Worst Type (January, 1986)

The Great Depression is usually placed in the 1930s, when unemployment climbed to over three million. The Great Depression in the South Wales coalfield started immediately after, and as a direct result of, the Miners’ Lock-out. The poverty of the mining families, especially those in the more militant pits where the sackings and victimisations were the hardest, is, literally, unimaginable. Those that could afford the journey left the area. Other miners simply drifted away from their families to seek some sort of work during the week in or around London, or to beg in the London streets. Almost as soon as he got back to his office in Russell Square, Cook found himself besieged by South Wales miners who came to the offices day by day to beg for money or a crust of bread.

(13) Arthur J. Cook, letter to Ramsay MacDonald (9th January, 1931)

I think you should know how some of us feel in regard to the action of the Labour Cabinet towards the mineworkers. I am terribly disappointed at the shabby way our men have been treated in the face of the attacks of the coal owners especially in South Wales. I think a Labour government would defend its own Mines Act and put up a fight against the coal owners attacking the mineworkers - but no - we are left to battle alone against the most vicious set of capitalists existing in this country. We have had nothing but lavish promises from a Labour government which makes it difficult and impossible for some of us to defend (it) in the future. It appears to me that our only hope is in our trade union movement. Had it not been for the splendid fight put up by the South Wales miners, huge reductions would have been forced upon them.

(14) Ben Tillett, The Daily Express (3rd November, 1931)

He (Arthur Cook) was terribly agitated about the Labour Party's collapse in the election, and said to me, "What has happened to the multitude to desert you and other old friends like this?" I tried to soothe him, and assured him that the cause was not dead, and would rise again. He grasped my hand and held it for about ten minutes, saying beseechingly, "Don't go, old man. Don't leave me." Then he seemed to pause a little, and murmured, "Goodbye, Ben." I left him then, knowing that the end was very near.