Harry Pollitt

Harry Pollitt,the second of six children of Samuel Pollitt, a blacksmith, was born in Droylsden, near Manchester, on 22nd November, 1890. His family had been active in radical politics in Lancashire since the early part of the 19th century. His great grandfather was a Chartist and his mother, Mary Pollitt. "Pollitt found in his mother both a confidante and a model of working-class dignity in the face of affliction. His own sense of injustice at family poverty, as three of his siblings died in infancy, was likewise fundamental to the visceral identification with his class that lay at the root of his political philosophy." (1)

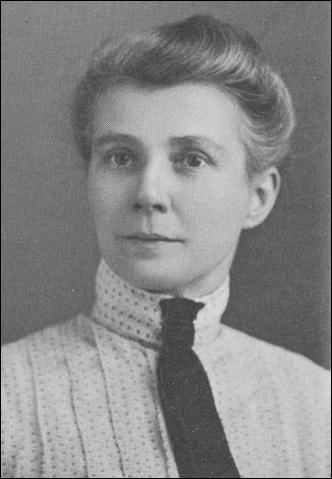

Mary Pollitt had worked in a cotton mill since she was twelve years of age. According to her son she rose at 4.30 a.m. to get ready for the 6 a.m. start. She rushed back to give the children's breakfast at 8 a.m. but she had to be back to work at 8.30. Dinner time, 12.30 to 1.25, brought another scramble home so that she could provide the children's dinner. Her working day did not end until 5.30 p.m. In the evenings she attended evening classes in economics and industrial history, and to meetings held by the Independent Labour. Mary Pollitt told her son that "she found in socialism the hope of a new and better future for mankind". (2)

Harry Pollitt grew up in extreme poverty and saw two of his siblings die: "His mother, like most working-class women, lost lost as many children in infancy as she brought up, for want of sufficient care, the right food, and enough time off from her exhausting job to look after herself and her babies." (3)

Harry Pollitt: Childhood Poverty

Pollitt was especially disturbed by the death of his sister, Winifred, in 1903. He recalled forty years later: "I would pay God out. I would pay everybody out for making my sister suffer." He claims that he was already convinced that people like his sister had an early death because of the unfair economic system. In thinking this "I was unconsciously voicing the wrongs of my class." (4)

Pollitt attended the local school. One of his teachers, Jessie Rathbone, considered him as "a brilliant scholar and a leader among his playmates". She said he gave lectures to the other pupils on the "evils of strong drink". Rathbone later claimed that "if Harry could have been educated in accordance with his abilities and apitudes, he could have become a Prime Minister instead of a leader of rebels". She added that she held his mother responsible for making him into a rebel. (5)

At the age of twelve he began work as a half-timer helping his mother with her four looms at the local textile factory. "Every time she put her shawl round me before going to the mill on wet or very cold mornings, I swore that when I grew up, I would pay the bosses out for the hardships she suffered. I hope I shall live to do it, and there will be no nonsense about it." (6)

The following year he left school and began an apprenticeship as a boilermaker at the Gorton Tank locomotive works. Mary Pollitt took him to meetings held by left-wing politicians. He was impressed by Philip Snowden, a militant and eloquent socialist speaker, who told the meeing that "only when capitalism had been abolished will it be possible to abolish poverty, unemployment and war". He also remembered a speech on women's suffrage made by Emmeline Pankhurst in July, 1906. (7)

Pollitt was an active figure in the Openshaw Socialist Society, and several important figures in the labour movement, including Robert Blatchford and Victor Grayson, were invited to speak at meetings. In 1911 he published his first pamphlet, Socialism or Social Reform? He argued that socialism is revolutionary because it means the replacement of the capitalist system by a new and different system based on "production for social use". In contrast, Social Reform "acts only upon effects and not causes" and therefore can be made use of by the capitalists as a palliative to weaken working-class militancy and "a means of staving off social revolution". (8)

Mary Pollitt became a convert to the ideas of Karl Marx and Harry received the first volume of Capital for his twenty-first birthday. After reading the book he claimed "I felt that I owned the world". He decided that he would devote his life to spread the word of Marxism. He made it clear that his mother played an important role in this: "She was my pal. I confided to her all my hopes and ambitions. She guided my every step." (9)

Mary Pollitt also trained her son to be a successful public speaker. He would get up on a chair at home and practice his speeches on her, and after a meeting she wanted to know every question he had been asked and how he had answered. She then offered her son advice on improving the quality of his speeches. Pollitt admitted in his autobiography, her main advice was "always explain a situation as plainly as possible, so that the workers will understand." (10)

On the "outdoor speaking pitches of northern England" he had begun to establish his reputation as a great orator. In January 1912, he became involved in the trade union movement by joining the Amalgamated Society of Boilermakers, Shipwrights, Blacksmiths and Structural Workers. "This was among the most conservative and exclusive of craft unions, and Pollitt was to remain deeply affected by its traditions of skill and respectability." (11)

Harry Pollitt found it difficult to join a political party he agreed with. He refused to join the Labour Party as its programme of immediate reforms "would obscure the class war issue". He found himself in opposition to the British Socialist Party (BSP): "Insofar as they entered into competition with the capitalist parties in offering to the people more reforms, they themselves would become a reformist party." He also had contempt for its leader, H. M. Hyndman, who he "disliked him for his arrogance and snobbishness from the first moment I set eyes on him". (12)

First World War

On the outbreak of the First World War Pollitt denounced it as "imperialist" conflict. In his first speech on the subject outside Yeomanry Barracks in the Moss Side district of Manchester he announced that he "would say a few words about the war and what the workers ought to do". (13) Some soldiers demanded that he sing "God Save the King" and when he refused he was beaten up. He was rescued by a woman who used her umbrella to get him free from their fists and feet. Once out of the crowd she said, "I'm a suffragette, and used to rough handling, good night and good luck". (14)

In 1915 Pollitt moved to Southampton and found work at Thorneycrofts Shipyard. In July that year Parliament passed the Munitions of War Act that prohibited strikes. The following month the government sent a senior official, Dr. Thomas Macnamara, to Thorneycrofts to ask the men to give up their holidays while the war lasted. At a delegate meeting, Pollitt told Macnamara: "The British and German workers had no quarrel, you are sending them to slaughter one another. Our stand for trade union rights is for the benefit of the lads at the front, if we give up what they have won they will never forgive us when they come home. There is no such thing as common sacrifice and you know it. Your class caused this war, mine wants to stop it." (15)

Pollitt returned to Manchester and was working in a small boilershop when news arrived of the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia. According to his biographer, John Mahon: "The impact of the Russian socialist revolution upon Pollitt was profound, it decided the future course of his life. Immediately, without hesitation, doubt or reservation, he took his stand in support of the Soviet Republic. His decision was no temporary fit of enthusiasm, to evaporate as did that of so many others, as capitalist and reformist disapproval hardened into hatred and repressive intervention... It was a passionate personal commitment impelling him to reject any prospect of his own aggrandisement through co-operation with the capitalist establishment and to devote his whole being to the service of the working class and the cause of socialism." (16)

Pollitt wrote about his reaction to events in Russia in his autobiography: "The thing that mattered was that lads like me had whacked the bosses and the landlords; had taken their factories, their lands and their banks... that was enough for me. These were the lads and lasses I must support through thick and thin. I was not concerned as to whether or not the Russian Revolution had caused bloodshed, been violent and the rest of it."

Pollitt had an important understanding of the history of political struggle in Britain and made reference to the Peterloo Massacre: "I had lived my life in Lancashire, had read and seen what kindhearted British bosses had done to the Lancashire working class. I knew about Peterloo." He stressed he was unwilling to consider the opinions of those Marxists who opposed the overthrow of the Provisional Government: "I had never heard of the dictatorship of the proletariat... I did not understand the significance of the polemics between one section of social democracy and another. All I was concerned about was that power was in the hands of lads like me and whatever conception of politics had made that possible was the correct one for me." (17)

At the end of the war Pollitt joined the Workers Socialist Federation, an organization formed by Sylvia Pankhurst who claimed "I am proud to call myself a Bolshevist". Pollitt was also active in the Hands off Russia campaign that was opposed to the British government providing help to White Army in the Russian Civil War. Pollitt was very impressed with Pankhurst who wrote that she had a "remarkable gift of extracting the last ounce of energy, as well as the last penny, from everyone with whom she came in contact, to help on the activities she directed." He also added that that he "felt for her the same sort of affection as existed between me and my mother". (18)

On 31st July, 1920, a group of revolutionary socialists, including Harry Pollitt, attended a meeting at the Cannon Street Hotel in London. The men and women were members of various political groups including the British Socialist Party (BSP), the Socialist Labour Party (SLP), Prohibition and Reform Party (PRP) and the Workers' Socialist Federation (WSF). It was agreed to form the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB). Arthur McManus was elected as the party's first chairman and Tom Bell and Harry Pollitt became the party's first full-time workers. (19)

The first resolution passed at the Communist Unity Convention covered the main aims of the new party: "The Communists in Conference assembled declare for the Soviet (or Workers' Councils) system as a means whereby the working class shall achieve power and take control of the forces of production. Declare the dictatorship of the proletariat as a necessary means of combating counter-revolution during the transition period between capitalism and communism, and stand for the adoption of these measures as a step towards the establishment of a system of complete communism wherein the means of production shall be communally owned and controlled. This Conference therefore establishes itself the Communist Party on the foregoing basis and declares its adhesion to the Communist International." (20)

Harry Pollitt was attracted to party member, Rose Cohen. According to Francis Beckett, the author of Enemy Within: The Rise and Fall of the British Communist Party (1995): "In the early 1920s Harry Pollitt fell in love with Rose Cohen, and proposed marriage - on her account, several times, and on his exuberant and perhaps exaggerated account fourteen times. They never lost their affection for each other.... She was clever, fluent, entertaining, and attractive... Everyone who knew her talks of her smile, but says she was quite unaware of its power." (21)

John Mahon, Pollitt's biographer, has pointed out that Rose's friend, Eva Reckitt, had a cottage at Houghton in Sussex. Reckitt later recalled that "Harry... was a great lover of the countryside and spent a great deal of time between the cottage at Houghton and that of another friend at Middleton." His favourite walk with Rose was to Houghton Bridge with its boats, tea places, the Bridge Hotel for a drink, and then on to Amberley. Mahon was greatly attracted to Rose Cohen, who had black hair, red cheeks, flashing eyes, a provocative smile and quick wit. But refused to take Harry seriously." She eventually rejected Pollitt to marry Max Petrovsky, a representative of the Comintern and went to live in Moscow. (22)

It is claimed that by 1921 the CPGB had 2,500 members. Albert Inkpin was elected as National Secretary of the CPGB. Later that year he was arrested and charged with printing and circulating Communist Party literature. He was found guilty and sentenced to six months in prison. Bob Stewart, the National Organiser for Scotland, was also arrested and charged with making seditious speeches. He was also found guilty and was sentenced to three months' hard labour in Cardiff Gaol. (23)

Harry Pollitt, Albert Inkpin, and Rajani Palme Dutt were charged with the task of implementing the organisational theses of the Comintern. As Jim Higgins has pointed out: "In the streamlined “bolshevised” party that came out of the re-organisation, all three signatories reaped the reward of their work. Inkpin was elected chairman of the Central Control Commission Dutt and Pollitt were elected to the party executive. Thus started the long and close association between Dutt and Pollitt. Palme Dutt, the cool intellectual with a facility for theoretical exposition, with friends in the Kremlin and Pollitt the talented mass agitator and organiser." (24)

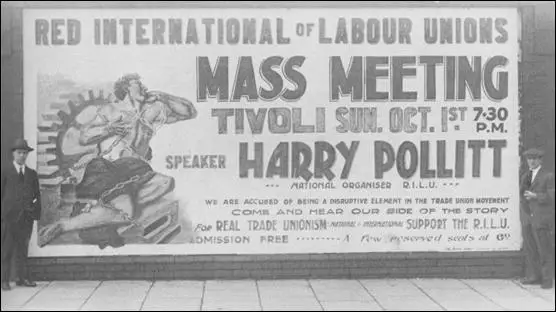

In 1924 Pollitt was appointed General Secretary of the National Minority Movement, a Communist-led united front within the trade unions. Pollitt worked alongside Tom Mann and according to one document the plan was "not to organize independent revolutionary trade unions, or to split revolutionary elements away from existing organizations affiliated to the T.U.C. but to convert the revolutionary minority within each industry into a revolutionary majority." The following year he married Marjory Edna Brewer, a schoolteacher who was also a member of the CPGB. (25)

On 25th July 1925, the Worker's Weekly, a newspaper controlled by the Communist Party of Great Britain, published an "Open Letter to the Fighting Forces" that had been written anonymously by Harry Pollitt. The article called on soldiers to "let it be known that, neither in the class war nor in a military war, will you turn your guns on your fellow workers, but instead will line up with your fellow workers in an attack upon the exploiters and capitalists and will use your arms on the side of your own class." (26)

After consultations with the Director of Public Prosecutions and the Attorney General, Sir Patrick Hastings, it was decided to arrest and charge, John Ross Campbell, the editor of the newspaper, with incitement to mutiny. The following day, Hastings had to answer questions in the House of Commons on the case. However, after investigating Campbell in more detail he discovered that he was only acting editor at the time the article was published, he began to have doubts about the success of a prosecution. (27)

The matter was further complicated when James Maxton informed Hastings about Campbell's war record. In 1914, Campbell was posted to the Clydeside section of the Royal Naval division and served throughout the war. Wounded at Gallipoli, he was permanently disabled at the battle of the Somme, where he was awarded the Military Medal for conspicuous bravery. Hastings was warned about the possible reaction to the idea of a war hero being prosecuted for an article published in a small circulation newspaper. (28)

At a meeting on the morning of the 6th August, Hastings told MacDonald that he thought that "the whole matter could be dropped". MacDonald replied that prosecutions, once entered into, should not be dropped under political pressure". At a Cabinet meeting that evening Hastings revealed that he had a letter from Campbell confirming his temporary editorship. Hastings also added that the case should be withdrawn on the grounds that the article merely commented on the use of troops in industrial disputes. MacDonald agreed with this assessment and agreed the prosecution should be dropped. (29)

On 13th August, 1924, the case was withdrawn. This created a great deal of controversy and MacDonald was accused of being soft on communism. MacDonald, who had a long record of being a strong anti-communist, told King George V: "Nothing would have pleased me better than to have appeared in the witness box, when I might have said some things that might have added a month or two to the sentence." (30)

Imprisonment of Communist Leaders

After the poor general election result in 1924, it has been argued that Ramsay MacDonald and other right-wing members of the Labour Party, decided that they wanted scapegoats, and who better than the communists? At the Labour Party conference following the election it was decided to exclude, not only the Communist Party as an organization, but also individual members. At this time the Communist Party had 10,730 members. (31)

On 4th August 1925, 12 party activists, Harry Pollitt, John Ross Campbell, Jack Murphy, Wal Hannington, Ernie Cant, Tom Wintringham, Hubert Inkpin, Arthur McManus, William Rust, Robin Page Arnot, William Gallacher and Tom Bell were arrested for being members of the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB) and were charged with violation of the Mutiny Act of 1797. The hearing at Bow Street was before Sir Chartres Biron, described by Gallacher as "an ideal subject for Dickens, majestic, pompous, fully convinced of his high responsibility as custodian of the law and safety of the realm." (45)

While the men were on remand the CPGB had a secret meeting. Bob Stewart later recalled what happened: "After discussion it was decided to elect an acting executive and officials, and that no publicity would be given to this, because naturally the new leaders could easily follow the twelve into prison, so an entire silence was maintained. To my astonishment I was elected acting general secretary . This was a new role for me, and also in new conditions. Before, I was always one of those in jail looking out at the fight. Now I was outside and with a heavy responsibility." (33)

Claims that it was a political trial was reinforced when Rigby Swift was appointed as judge. He was a member of the Conservative Party and was elected to represent St Helens in December 1910 but was easily beaten by James Sexton in the general election that followed the end of the First World War. In June 1920 he was appointed by his friend, Frederick Smith, Lord Birkenhead, the Lord Chancellor, as judge of the High Court of Justice. The decision was welcomed by the right-wing press. The Daily Mail wrote that "Mr. Rigby Swift has long been marked out for judgeship" and The Times added that "no appointment could be met with greater approval". (34)

Tom Bell, the author of British Communist Party (1937), the CPGB responded as if it was a political trial. "The Political Bureau discussed the procedure of the trial and decided that Campbell, Gallacher and Pollitt should defend themselves; their speeches were prepared, and approved by the Political Bureau." (35) Their three speeches "made an exposition of Communist politics, theory and practice which thousands of workers read with appreciation." (36)

Pollitt's 15,000 word speech took three hours. He argued that the political motivation behind the prosecution was the proposed General Strike as the "government sought to remove from the political arena the most effective exponents of united action by the working class to aid the miners". He then warned the jury against the newspaper build-up of prejudice against the Communists. Pollitt went on to say that "the destruction of Monarchies, of Tsarism, not as the result of Communist propaganda, but as the result of conditions created by capitalism." (37)

To challenge the legality of the proceedings Sir Henry Slesser was engaged to defend the others. During the trial Judge Rigby Swift declared that it was "no crime to be a Communist or hold communist opinions, but it was a crime to belong to this Communist Party." It was argued that the Soviet Union had given the CPGB £14,000. During the trial Gallacher showed this money was the income from the sale of newspapers and fees paid by the 5,000 members. (38)

After a trial that lasted eight days, the twelve defendants were found guilty on all charges. Judge Swift told the men: "The jury have found you twelve men guilty of the serious offence of conspiracy to publish seditious libels and to incite people to induce soldiers and sailors to break their oaths of allegiance. It is obvious from the evidence that you are members of an illegal party carrying on illegal work in this country. Five of you, Inkpin, Gallacher, Pollitt, Hannington and Rust will go to prison for twelve months."

Judge Swift then went on to say: "You remaining seven have heard what I have had to say about the society to which you belong. You have heard me say it must be stopped.... Those of you who will promise me that you will have nothing more to do with this association or the doctrine it preaches, I will bind over to be of good behaviour in the future. Those of you who do not promise will go to prison." (39)

Jack Murphy, Ernie Cant, Tom Wintringham, Arthur McManus, Robin Page Arnot, and Tom Bell all refused and were each sentenced to six months. (40) As one commentator pointed out: "And there it was, men supposedly found guilty of the worst charges in the crime calendar were to be let off all they had to do was to cease being Communists. Very touching, but it gave away the aim of the whole trial, which was to try and destroy the Communist Party and so behead the working-class movement." (41)

On his release from prison in 1926, Harry Pollitt married Marjory Edna Brewer. They had two children, Jean and Brian. Pollitt's activities with the National Minority Movement came under increasing attack from other left-wing organisations and in November 1927, Walter Citrine, Secretary of the Trades Union Congress, published a series of articles entitled "Democracy or Disruption" in The Labour Monthly. Pollitt responded by asking why Citrine spent so much effort "attacking revolutionary workers... instead of using his position to help reorganise the trade union movement so that it may more effectively fight capitalism, and ultimately become strong enough to participate actively in its revolutionary overthrow." (42)

The Great Purge

In 1929 Pollitt was elected as General Secretary of the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB). Over the next few years he was a loyal supporter of Joseph Stalin in his attempts to purge the followers of Leon Trotsky in the Soviet Union. On 1st December, 1934, Sergey Kirov was assassinated by a young party member, Leonid Nikolayev. It was argued that the conspiracy was led by Trotsky. This resulted in the arrest of Lev Kamenev, Gregory Zinoviev, Nikolay Bukharin, Ivan Smirnov, Mikhail Tomsky and Alexei Rykov and other party members who had been critical of Joseph Stalin. (43) In the Daily Worker, Pollitt argued that the proposed trial represented "a new triumph in the history of progress". (44)

The first ever show show trial took place in August, 1936, of sixteen party members. Yuri Piatakov accepted the post of chief witness "with all my heart." Max Shachtman pointed out: "The official indictment charges a widespread assassination conspiracy, carried on these five years or more, directed against the head of the Communist party and the government, organized with the direct connivance of the Hitler regime, and aimed at the establishment of a Fascist dictatorship in Russia. And who are included in these stupefying charges, either as direct participants or, what would be no less reprehensible, as persons with knowledge of the conspiracy who failed to disclose it?" (45)

The men made confessions of their guilt. Lev Kamenev said: "I Kamenev, together with Zinoviev and Trotsky, organised and guided this conspiracy. My motives? I had become convinced that the party's - Stalin's policy - was successful and victorious. We, the opposition, had banked on a split in the party; but this hope proved groundless. We could no longer count on any serious domestic difficulties to allow us to overthrow. Stalin's leadership we were actuated by boundless hatred and by lust of power." (46)

Gregory Zinoviev also confessed: "I would like to repeat that I am fully and utterly guilty. I am guilty of having been the organizer, second only to Trotsky, of that block whose chosen task was the killing of Stalin. I was the principal organizer of Kirov's assassination. The party saw where we were going, and warned us; Stalin warned as scores of times; but we did not heed these warnings. We entered into an alliance with Trotsky." (47)

On 24th August, 1936, Vasily Ulrikh announced that all sixteen defendants were sentenced to death by shooting. The following day Soviet newspapers carried the announcement that all sixteen defendants had been put to death. This included the NKVD agents who had provided false confessions. Joseph Stalin could not afford for any witnesses to the conspiracy to remain alive. Edvard Radzinsky, the author of Stalin (1996), has pointed out that Stalin did not even keep his promise to Kamenev's sons and later both men were shot. (48)

Most journalists covering the trial were convinced that the confessions were statements of truth. The Observer reported: "It is futile to think the trial was staged and the charges trumped up. The government's case against the defendants (Zinoviev and Kamenev) is genuine." (49) The The New Statesman commented: "Very likely there was a plot. We complain because, in the absence of independent witnesses, there is no way of knowing. It is their (Zinoviev and Kamenev) confession and decision to demand the death sentence for themselves that constitutes the mystery. If they had a hope of acquittal, why confess? If they were guilty of trying to murder Stalin and knew they would be shot in any case, why cringe and crawl instead of defiantly justifying their plot on revolutionary grounds? We would be glad to hear the explanation." (50)

In January, 1937, Yuri Piatakov, Karl Radek, Grigori Sokolnikov, and fifteen other leading members of the Communist Party were put on trial. They were accused of working with Leon Trotsky in an attempt to overthrow the Soviet government with the objective of restoring capitalism. Piatakov had been the main witness against Lev Kamenev and Gregory Zinoviev in 1936: "After they saw that Piatakov was ready to collaborate in any way required, they gave him a more complicated role. In the 1937 trials he joined the defendants, those whom he had meant to blacken. He was arrested, but was at first recalcitrant. Ordzhonikidze in person urged him to accept the role assigned to him in exchange for his life. No one was so well qualified as Piatakov to destroy Trotsky, his former god and now the Party's worst enemy, in the eyes of the country and the whole world. He finally agreed I to do it as a matter of 'the highest expediency,' and began rehearsals with the interrogators." (51)

Yuri Piatakov and twelve of the accused were found guilty and sentenced to death. Maria Svanidze, who was later herself to be purged by Stalin wrote in her diary: "They arrested Radek and others whom I knew, people I used to talk to, and always trusted.... But what transpired surpassed all my expectations of human baseness. It was all there, terrorism, intervention, the Gestapo, theft, sabotage, subversion.... All out of careerism, greed, and the love of pleasure, the desire to have mistresses, to travel abroad, together with some sort of nebulous prospect of seizing power by a palace revolution. Where was their elementary feeling of patriotism, of love for their motherland? These moral freaks deserved their fate.... My soul is ablaze with anger and hatred. Their execution will not satisfy me. I should like to torture them, break them on the wheel, burn them alive for all the vile things they have done." (52)

These convictions were criticised by Leon Trotsky, who was living in exile in Mexico City. In his article The Trial of the Seventeen, he asked: "How could these old Bolsheviks who went through the jails and exiles of Czarism, who were the heroes of the civil war, the leaders of industry, the builders of the party, diplomats, turn out at the moment of 'the complete victory of socialism' to be saboteurs, allies of fascism, organizer of espionage, agents of capitalist restoration? Who can believe such accusations? How can anyone be made to believe them. And why is Stalin compelled to tie up the fate of his personal rule with these monstrous, impossible, nightmarish juridical trials?" (53)

William Gallacher went to Moscow to express his concerns about the Great Purge. He went to see Georgi Dimitrov who told him: "Comrade Gallacher, it is best that you do not pursue these matters." Gallacher took this advice and remained a staunch Stalinist. He told his family that "not speaking the language and being shepherded about everywhere, it was hard to know what was really going on." The Comintern laid down the correct line for the CPGB to take. Trotsky's supporters were "mean degenerates" and "abominable traitors". (54)

In 1936, Victor Gollancz, formed the Left Book Club. It had over 45,000 and 730 local discussion groups, and it estimated that these were attended by an average total of 12,000 people every fortnight. The Left Book Club published several books written by members of the Communist Party of Great Britain. This included the defence of the Soviet Show Trials. This included the "suppression of some of his (Gollancz) most fundamental instincts and cherished beliefs" and included his "ready acceptance of Stalinist propaganda concerning the Moscow trials, despite the disquiet widely evident among socialists". (55)

Gollancz worked very closely with Harry Pollitt. At the Royal Albert Hall in February 1937, Pollitt made clear that while the Club was not a communist organisation, "its publications and discussions revealed for the first time in Britain a hunger for Marxism." It brought forward new writers who "expressed in their creative writing an understanding of what Marxism means and are influencing sections to whom a short time ago the name of Marx was a bogey." (56)

Gollancz was vice-president of the National Committee for the Abolition of the Death Penalty but he agreed to Pollitt's suggestion that he published a defence of the prosecution and execution of former members of the Soviet government. Dudley Collard was approached to write a book on the legality of the Soviet Show Trials. The book was entitled Soviet Justice and the Trial of Radek and Others. (57)

In March 1937 Max Petrovsky was arrested as a supporter of Leon Trotsky. His wife, Rose Cohen, also became a suspect and Tom Bell, a colleague on the Moscow Daily News was instructed to spy on her. According to a British Intelligence report: "Bell was instructed by his chief in the office to be very friendly with her and not to tell her that she was being watched, also to discuss her husband's arrest as often as possible and... to elicit her views on the matter. He reported that she never spoke of her husband as being guilty, and although he put it to her that he must be guilty, or implicated in some way, otherwise the OGPU would not arrest him, she always replied: An error has been made somewhere." (58)

Rose Cohen was also arrested on 13th August 1937 and charged with being "a member of an anti-Soviet organisation existing in the ECCI (Comintern) and a resident agent of British Intelligence". The day after the news came out that Cohen had been arrested, the The Daily Worker published an editorial: "The National Government is starting up a new attack on Anglo-Soviet relations. As a pretext for this they are using the case of the arrest of a former British subject on a charge of espionage. The individual concerned, it is understood, is married to a Soviet citizen and thereby assumed Soviet citizenship alike in the eyes of Soviet law as of international law... The British Government has no right whatever to interfere in the internal affairs of another country and of its citizens." The newspaper also criticised the Daily Herald for bringing up the case and dismissed its "attack upon the country of socialism... This is not the first time that the Daily Herald has lent itself to the most poisonous attacks on the Soviet Union." (59)

William Gallacher went to see Georgi Dimitrov and asked about Rose Cohen and other foreigners who had disappeared. Dimitrov looked at him gravely for a few moments, then said: "Comrade Gallacher, it is best that you do not pursue these matters." Harry Pollitt also made representations on behalf of Rose Cohen. Privately he was distraught but was unwilling to make too much fuss. (60)

However, as his biographer, Kevin Morgan, has pointed out: "Rose Cohen, who was sucked instead into the maelstrom of Stalin's terror through her ill-fated preference for the Comintern representative Petrovsky. Her sentencing by the Soviet authorities, though not her death, was made known to British communists in 1937, but even in the case of a woman he had loved, Pollitt's private representations were not accompanied by any public protest or disavowal." Rose Cohen was found guilty on 28th November 1937 and shot later that day. (61)

John Ross Campbell was the foreign correspondent of the Daily Worker in the Soviet Union and became a loyal supporter of Joseph Stalin in his attempts to purge the followers of Leon Trotsky. As Campbell was the CPGB representative in the Soviet Union, it is unlikely that he was unaware of what was really going on. (62) Along with Rajani Palme Dutt and Denis Nowell Pritt, Campbell were "enthusiastic apologists for the Moscow frame-up trials". (63)

Campbell wrote on 5th March 1938: "Every weak, corrupt or ambitious enemy of socialism within the Soviet Union has been hired to do dirty, evil work. In the forefront of all the wrecking, sabotage and assassination is Fascist agent Trotsky. But the defences of the Soviet Union are strong. The nest of wreckers and spies has been exposed before the world and brought before the judgement of the Soviet Court. We know that Soviet justice will be fearlessly administered to those who have been guilty of unspeakable crimes against Soviet people. We express full confidence in our Brother Party." (64)

In 1939 the Left Book Club published Campbell's Soviet Policy and its Critics, in defence of the Great Purge in the Soviet Union. He agreed with Dudley Collard that the main issue between Trotsky and Stalin was over the issue of "socialism in one country". He quoted Stalin as saying: "Our Soviet society has already, in the main, succeeded in achieving Socialism... It has created a socialist system; i.e., it has brought about what Marxists in other words call the first, or lower phase of Communism. Hence, in the main, we have already achieved the first phase of Communism, Socialism." (65)

The Second World War

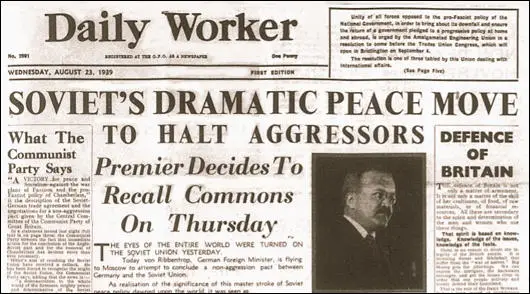

On 23rd August, 1939, Joseph Stalin signed the Soviet-Nazi Pact with Adolf Hitler. However, long-time loyalist, John Ross Campbell, felt he could no longer support this policy. "We started by saying we had an interest in the defeat of the Nazis, we must now recognise that our prime interest in the defeat of France and Great Britain... We have to eat everything we have said." Other leaders of the CPGB agreed with Campbell a statement was issued that "declared its support of all measures necessary to secure the victory of democracy over fascism". (66)

Harry Pollitt, published a 32-page pamphlet, How to Win the War (1939): "The Communist Party supports the war, believing it to be a just war. To stand aside from this conflict, to contribute only revolutionary-sounding phrases while the fascist beasts ride roughshod over Europe, would be a betrayal of everything our forebears have fought to achieve in the course of long years of struggle against capitalism.... The prosecution of this war necessitates a struggle on two fronts. First to secure the military victory over fascism, and second, to achieve this, the political victory over the enemies of democracy in Britain." (67)

On 24th September, Dave Springhall, a CPGB member who had been working in Moscow, returned with the information that the Communist International characterised the war as an "out and out imperialist war to which the working class in no country could give any support". He added that "Germany aimed at European and world domination. Britain at preserving her imperialist interests and European domination against her chief rival, Germany." (68)

At a meeting of the Central Committee on 2nd October 1939, Rajani Palme Dutt demanded "acceptance of the (new Soviet line) by the members of the Central Committee on the basis of conviction". He added: "Every responsible position in the Party must be occupied by a determined fighter for the line." Bob Stewart disagreed and mocked "these sledgehammer demands for whole-hearted convictions and solid and hardened, tempered Bolshevism and all this bloody kind of stuff."

William Gallacher agreed with Stewart: "I have never... at this Central Committee listened to a more unscrupulous and opportunist speech than has been made by Comrade Dutt... and I have never had in all my experience in the Party such evidence of mean, despicable disloyalty to comrades." Harry Pollitt joined in the attack: "Please remember, Comrade Dutt, you won't intimidate me by that language. I was in the movement practically before you were born, and will be in the revolutionary movement a long time after some of you are forgotten."

Harry Pollitt then made a passionate speech about his unwillingness to change his views on the invasion of Poland: "I believe in the long run it will do this Party very great harm... I don't envy the comrades who can so lightly in the space of a week... go from one political conviction to another... I am ashamed of the lack of feeling, the lack of response that this struggle of the Polish people has aroused in our leadership." (69)

However, when the vote was taken, only John Ross Campbell, Harry Pollitt, and William Gallacher voted against. Pollitt was forced to resign as General Secretary and he was replaced by Rajani Palme Dutt and William Rust took over Campbell's job as editor of the Daily Worker. Pollitt, then agreed to disguise this conflict and issued a statement saying it was "nonsense and wishful thinking the attempts in the press to create the impression of a crisis in the Party". (70)

Over the next few weeks the newspaper demanded that Neville Chamberlain respond to Hitler's peace overtures. Palme Dutt also published a new pamphlet, Why This War? explaining the new policy of the CPGB. Campbell and Pollitt were both removed from the Politburo. (71) Campbell also "subsequently rationalized the Comintern's position and publicly confessed to error in having opposed it." (72) Douglas Hyde claims that despite the fact that Pollitt was the general secretary, Palme Dutt was clearly the "most powerful man in the Party". (73)

Fred Copeman was one of those who resigned from the Communist Party over this issue: "It has yearly become harder to make excuses to my conscience each time an action of the Soviet Government or the Communist Party has cut across my interpretation of personal freedom. The decision of the Russian Government to withhold arms to the Spanish Republic, in order that the Spanish Communist Party could gain a political point, needed some understanding. The trials of old Bolsheviks were even harder to swallow. The Soviet attack on Finland I found hard to accept, but was unable to prove completely wrong. Their alliance with the Nazis in 1939, aligned with the complete reversal of policy by our own Communist Party, forced me to begin to look elsewhere for an ideology and philosophy so fundamentally true that it would be possible for me to find real happiness in giving my all in the struggle for its acceptance by mankind." (74)

William Rust, John Ross Campbell and Douglas Hyde (1939)

On 22nd June 1941 Germany invaded the Soviet Union. That night Winston Churchill said: "We shall give whatever help we can to Russia." The CPGB immediately announced full support for the war and brought back Harry Pollitt as general secretary. As Jim Higgins has pointed out Palme Dutt's attitude towards the war was "immediately transformed into an anti-fascist crusade." (75)

In the early stages of the Second World War, the Home Secretary, Herbert Morrison, banned the Daily Worker. Following the German army's invasion of the Soviet Union in Operation Barbarossa, in June 1941, a campaign supported by Professor John Haldane and Hewlett Johnson, the Dean of Canterbury, began to allow the newspaper to be published. On 26th May 1942, after a heated debate, the Labour Party carried a resolution declaring the Government must lift the ban on the newspaper. The ban was lifted in August 1942. (76)

As Francis Beckett has pointed out: "Suddenly the Communist Party was popular and respectable, because Stalin's Russia was popular and respectable, and because at a time of war, Communists were able to wave the Union Jack with the best of them. Party leaders appeared on platforms with the great and the good. Membership soared: from 15,570 in 1938 to 56,000 in 1942." (77)

Khrushchev's de-Stalinzation Policy

During the 20th Party Congress in February, 1956, Nikita Khrushchev launched an attack on the rule of Joseph Stalin. He condemned the Great Purge and accused Stalin of abusing his power. He argued: "Stalin acted not through persuasion, explanation and patient co-operation with people, but by imposing his concepts and demanding absolute submission to his opinion. Whoever opposed this concept or tried to prove his viewpoint, and the correctness of his position, was doomed to removal from the leading collective and to subsequent moral and physical annihilation. This was especially true during the period following the 17th Party Congress, when many prominent Party leaders and rank-and-file Party workers, honest and dedicated to the cause of communism, fell victim to Stalin's despotism." (78)

Harry Pollitt found it difficult to accept these criticisms of Stalin and said of a portrait of his hero that hung in his living room: "He's staying there as long as I'm alive". Francis Beckett pointed out: "Pollitt believed, as did many in the 1930s, that only the Soviet Union stood between the world and universal Fascist dictatorship. On balance, he reckoned Stalin was doing more good than harm; he liked and admired the Soviet leader; and persuaded himself that Stalin's crimes were largely mistakes made by subordinates. Seldom can a man have thrown away his personal integrity for such good motives." (79)

However, according to his biographer, John Mahon, Pollitt found Khrushchev's speech upsetting: "Pollitt was far too human a person to regard the Stalin disclosures with personal detachment, they were as painful for him as far for thousands of other responsible Communists, and he was fully aware that they were giving rise to new and complex problems for the Party. Immediately following the Congress, he showed visible signs of physical exhaustion." On 25th April, 1956, he experienced a loss of ability to read following a haemorrhage behind the eyes. Unable to do his job properly he resigned as general secretary of the Communist Party. (80)

Harry Pollitt died of a on 27th June, 1960 and was cremated at Golders Green ten days later.

Primary Sources

(1) John Mahon, Harry Pollitt: A Biography (1976)

The impact of the Russian socialist revolution upon Pollitt was profound, it decided the future course of his life. Immediately, without hesitation, doubt or reservation, he took his stand in support of the Soviet Republic. His decision was no temporary fit of enthusiasm, to evaporate as did that of so many others, as capitalist and reformist disapproval hardened into hatred and repressive intervention.

It was not a vision of heaven on earth, idealist dream to fade in the stern realities of the desperate struggle for survival. It was not a patronising intellectual approval made from moral heights to be withdrawn in due course on equally high moral grounds. It was conscious political support to be sustained, indeed to wax in conviction in the anxious years when the young Soviet Republic, attacked by fourteen capitalist powers, seemed doomed, and to endure for the remaining forty-three years of his life. It was a class conscious political understanding of the movement of history, of the significance to all working mankind of the breach of the imperialist front in Russia. It was a passionate personal commitment impelling him to reject any prospect of his own aggrandisement through co-operation with the capitalist establishment and to devote his whole being to the service of the working class and the cause of socialism.

(2) Harry Pollitt, Serving My Time (1940)

The thing that mattered was that lads like me had whacked the bosses and the landlords; had taken their factories, their lands and their banks... that was enough for me. These were the lads and lasses I must support through thick and thin. I was not concerned as to whether or not the Russian Revolution had caused bloodshed, been violent and the rest of it. I had lived my life in Lancashire, had read and seen what kindhearted British bosses had done to the Lancashire working class. I knew about Peterloo.

I had never heard of the dictatorship of the proletariat, or the expression `Soviet Power'.... I did not understand the significance of the polemics between one section of social democracy and another. All I was concerned about was that power was in the hands of lads like me and whatever conception of politics had made that possible was the correct one for me.

(3) Harry Pollitt, The Communist (30th September 1922)

The demand of the Shipbuilding Employers' Federation that the wages of the shipyard workers shall be reduced a further 10s. per week, raises once more the problem of how far are the employers to be permitted to go in their steady lowering of wages, before any united action taken to challenge their continual encroachments.

For sheer callousness and brutality the action of the shipyard bosses in launching this further demand at their workers is surely unparalleled in Labour history. First it was a demand for a reduction of 6s. per week immediately after the defeat of the miners last year. When this demand was made, the Press simultaneously launched a campaign to emphasise what reduced labour costs meant to the coal markets and how that factor would stimulate trade. The same arguments were used in reference to shipbuilding and the atmosphere created favourable to accepting the 6s. cut in two instalments.

When this was finally accepted without any resistance being offered, the employers soon worked for the 12½ per cent. to be taken off shipbuilders' wages. After lengthy negotiations a settlement was agreed on that the 12½ per cent. should come off in three instalments: again no effective resistance was offered and the very week that the last instalment was taken off, saw the shipyard unions in conference with the employers to discuss the demand of the latter that a further 26/6 should be taken off the shipyard workers' wages. This was the last straw, and on a ballot being taken there was a large majority in favour of refusing to accept this reduction and a lockout of all shipyard workers took place. This was contemporary with the engineers' lockout on managerial functions and, whilst it was known that all previous reductions had afterwards been forced on the engineering unions, and whatever terms were arranged so far as the 26/6 was concerned would afterwards be forced on the engineering unions, no attempt was made to combine these two forces.

(4) Harry Pollitt, speech (August 1928)

Last November a notice appeared in an important capitalist newspaper, to the effect that Mr. W. M. Citrine, Secretary of the Trades Union Congress, was about to write a series of articles exposing the activities of Communists in the trade unions.

Shortly afterward, a series of articles commenced in "The Labour Magazine," entitled, "Democracy or Disruption," by W. M. Citrine. They are now being used all over the country as the basis of the attack on the Minority Movement. The articles have been written at some length with the purpose of putting "paid" to the Minority Movement.

We are sorry that Mr. Citrine has had all his trouble for nothing, for the representation at our annual conference, our increasing individual membership and increasing circulation of our various trade union papers, are all indications that in spite of Citrine's attack and his control of the trade union machine, the Minority Movement was never more alive.

The trade unionists who pay Mr. Citrine his £750 a year are, however, entitled to demand to know why all this time, money and energy, have been spent by the Secretary of the T.U.C. in attacking revolutionary workers (at the same time, of course, he was hand-in-glove with Mond and his associates), instead of using his position to help reorganise the trade union movement so that it may more effectively fight capitalism, and ultimately become strong enough to participate actively in its revolutionary overthrow.

(5) Harry Pollitt, The Communist International (5th August 1935)

The October Revolution in Russia in 1917 sent an electric thrill through the war-weary workers of the world. In our lifetime, the taunt of the capitalists, such as Churchill, that the workers are "not fit to govern" has been hurled back at them with a rebound that day by day is having its revolutionizing effect all over the world.

On the ruins and decadence of tsardom, out of a backward agricultural country, workers and peasants, under the leadership of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, led by Comrades Lenin and Stalin, have built up a new, powerful Socialist country that has to be reckoned with by every capitalist government the world over.

This transformation has been wrought despite every conceivable obstacle and difficulty, from famine and ruin to carefully prepared wrecking, organized and financed by counter-revolutionaries from abroad. It has been done on the unshakeable basis of loyalty to revolutionary principles and faith in the working class.

It was but natural that the October Revolution should have exercised a tremendous influence on the world labor movement. The contrast between the revolutionary conquest of power in Russia, where alone the Bolsheviks, under Lenin's leadership, had a consistently revolutionary line against the imperialist war, was in such marked contrast to the policy of the reformist leaders in other countries.

The formation of Communist Parties out of the scattered revolutionary sects, the creation of the Communist International, giving for the first time a centralized leadership to the class struggle all over the world; impetus to national revolutionary struggles in the colonial countries - these were events of historic importance. But the influence of the Social-Democratic leaders was still strong, and their cunning and demagogy knew no bounds. Platonic references to the Russian Revolution were the order of the day, and always with the aim of dampening down and diverting the revolutionary struggle in their own countries into the safe capitalist channels of parliamentary democracy and the denial of the armed conquest of power and the dictatorship of the proletariat.

Social-Democracy referred to the fact that tsarism was reactionary; there was no freedom, no legal labor movement in Russia; revolution was the only course for the workers to take. Not so in the western capitalist democratic countries. There, parliament stood waiting to be captured, and through this, Socialism could be built.

This "easy path" to Socialism prevailed with decisive sections of the masses who, at the same time, were undoubtedly ready to defend the Soviet Union. This was clearly seen in the "Hands-Off-Russia" movements that exercised great influence in the capitalist countries, in the strike of London dockers on "The Jolly George", and in the international solidarity displayed during the famine of 1921-22.

(6) Harry Pollitt, speech (February 1937)

In the name of the Executive Committee of the Communist International it is my duty on its behalf to pay its tribute to the memory of one of our most devoted, loyal and brillant Communist leaders, and in equal measure to pay its tribute to those score of other British Communists, who have, with Comrade Fox at their head, so courageously distinguished themselves by their coolness, bravery and discipline in the face of what appeared to be overwhelming odds.

In the case of Comrade Fox there was no economic reason why he should join our Party, the Communist Party. He came from a deep sense of intellectual conviction, and from the moment he took out his Party card, his life was dedicated to the cause of Communism. Whether as an author, a journalist, or as an instructor of. our factory groups in various parts of London, Comrade Fox has undoubtedly influenced the thoughts of thousands of working men and women, and also a big section of the professional classes of this country.

Comrades, we do not meet here as mourners for whom all is darkness and grief. We meet here as comrades in arms of those comrades whom we knew so intimately and so well, who have given that most precious thing that man can give - life - to the cause they believed in, and for which they were prepared to make the supreme sacrifice. We pledge ourselves to their families, their wives, their sweethearts, and in many cases, unfortunately, their children, that we will avenge their death, that we will show ourselves worthy of their trust and of their remarkably high example.

Friends of Spain in this audience who are not members of the Communist Party will pardon me if I refer with pride to the achievements that have been carried out by all Sections of the Communist International in support of the Spanish government. Without the existence of this International of steeled and. disciplined revolutionary fighters, the material and moral forms of aid sent to Spain would have been impossible of accomplishment. The dream of Marx and Engels has been realized - that dream which dominated them when they formed the First International - that one day there would arise a really single world party, that could mobilize the best of the people in every country to come to the assistance of comrades in other lands fighting a deadly enemy.

Comrades, the International Brigade, now covering itself with such honor and glory in Spain, is a real people's army. It is an army composed of the best anti-fascist fighters of all countries. We are proud tonight to declare that 750 young men from this country now form a British battalion of the International Brigade, and we pledge ourselves that within the course of the next two or three days the 750 will become a thousand.

The 750 boys who have gone from this country have gone without any fuss; it has all been done very quietly, no press photographers to see them off, but they got there, and when they got there they went to Madrid where the fighting has to be done, where the real danger spots lie. In going they have been fortified by the knowledge that they take with them the good wishes of every sincere and genuine anti-fascist in this country. Labor men and Socialists, Communists and liberals, doctor and writer, docker and intellectual, have all found it possible to sink certain of their own party and political aims in a united endeavor to defeat the common foe - fascism.

It would be a crime against the whole future perspective of working class advance, a crime against the whole future perspective of peace, if that single idea now dominating men who, in thousands, look death in the face in Spain - to bring about the defeat of fascism - did not also become the driving force of all our efforts to build up a united labor movement and fighting People's Front of all the democratic British people.

Comrades, we take legitimate pride in what comrades like General Kleber, Ludwig Renn, Hans Beimler, André Marty have said of the work of the British battalion in the Brigade. General Kleber has declared that when there is a particularly tight corner calling for coolness and courage, he has only to ask for the British Section, and men go immediately to that tight corner; and when that happens he feels safe that the objective they are to defend will be held to the very last. Their coolness and bravery have endeared them to all who have come into contact with them, and especially has the British Brigade inspired the Spanish militia who fight alongside them in a way that in life itself - in all to many cases death - has shown that international solidarity is not a First of May slogan, but a living reality for the best of our people.

The British Brigade has retrieved the honorable traditions of the British labor movement; it has upheld the fine democratic traditions that have characterized the fight on behalf of liberty. When the great poet Byron went to Greece to fight for liberty; when in a later period Comrade Brailsford fought for liberty in Greece - these are the examples our British comrades are following today in the conditions of our time.

(7) Daniel Gray, Homage to Caledonia (2008)

The dispute began when Battalion political commissar Walter Tapsell claimed that the promotions of Scots George Aitken (to Brigade Commissar) and Jock Cunningham (to Battalion commander) had left the two men isolated from regular Brigaders. Tapsell wrote that, "Aitken's temperament has made him distrusted and disliked by the vast majority of the British Battalion who regard him as being personally ambitious and unmindful of the interests of the Battalion and the men." Meanwhile, Cunningham, "fluctuates violently between hysterical bursts of passion and is openly accused by Aitken of lazing about the Brigade headquarters doing nothing." Assistant Brigade Commissar at Albacete, Dave Springhall, weighed in, claiming that the Battalion's entire leadership structure had collapsed under the pressures brought on by defeat at Brunete.

With an amicable resolution impossible in Spain, all parties involved were summoned back to London for a meeting with CPGB leader Harry Pollitt. At its conclusion, Pollitt told Aitken, Cunningham and Bert Williams (a political commissar with the Abraham Lincoln Battalion) to remain in Britain, while Fred Copeman (commander of the British Battalion) and Tapsell were to return to Spain. Aitken and Cunningham, though barely on speaking terms themselves, were apoplectic at the decision, and the former wrote a 10-page letter of "emphatic protest" to the CPGB, in response to this monstrous injustice".

Within a matter of months, both had resigned from the Party, and the leadership of the British Battalion had been radically reshaped. As part of its restructuring, the Battalion became an official part of the republican army, meaning popular six month terms of service were now prohibited. Disputes at the top of the hierarchy had undermined soldier morale and damaged the reputation of the Brigades on a level that the smattering of desertions at the bottom never could.

(8) Harry Pollitt, How to Win the War (1939)

The Communist Party supports the war, believing it to be a just war. To stand aside from this conflict, to contribute only revolutionary-sounding phrases while the fascist beasts ride roughshod over Europe, would be a betrayal of everything our forebears have fought to achieve in the course of long years of struggle against capitalism... The prosecution of this war necessitates a struggle on two fronts. First to secure the military victory over fascism, and second, to achieve this, the political victory over the enemies of democracy in Britain.

Student Activities

The Outbreak of the General Strike (Answer Commentary)

The 1926 General Strike and the Defeat of the Miners (Answer Commentary)

The Coal Industry: 1600-1925 (Answer Commentary)

Women in the Coalmines (Answer Commentary)

Child Labour in the Collieries (Answer Commentary)

Child Labour Simulation (Teacher Notes)

1832 Reform Act and the House of Lords (Answer Commentary)

The Chartists (Answer Commentary)

Women and the Chartist Movement (Answer Commentary)

Benjamin Disraeli and the 1867 Reform Act (Answer Commentary)

William Gladstone and the 1884 Reform Act (Answer Commentary)

Richard Arkwright and the Factory System (Answer Commentary)

Robert Owen and New Lanark (Answer Commentary)

James Watt and Steam Power (Answer Commentary)

Road Transport and the Industrial Revolution (Answer Commentary)

Canal Mania (Answer Commentary)

Early Development of the Railways (Answer Commentary)

The Domestic System (Answer Commentary)

The Luddites: 1775-1825 (Answer Commentary)

The Plight of the Handloom Weavers (Answer Commentary)

Health Problems in Industrial Towns (Answer Commentary)

Public Health Reform in the 19th century (Answer Commentary)

Classroom Activities by Subject