1911 National Insurance Act

During his speech on the People's Budget, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, David Lloyd George, pointed out that Germany had a compulsory national insurance against sickness since 1884. He argued that he intended to introduce a similar system in Britain. With a reference to the arms race between Britain and Germany he commented: "We should not emulate them only in armaments." (1)

In the autumn of 1908 Winston Churchill advocated the introduction of unemployment insurance. The scheme was restricted to trades which suffered from cyclical unemployment (shipbuilding, engineering and construction) and excluded those in decline, those with a large amount of casual labour and those with substantial short-time working (such as mining and cotton spinning). It would cover only about two million workers. The plan was that employees would contribute twice as much per week as the State and employers. The benefit would only be paid for a maximum of fifteen weeks and at a low enough rate to "imply a sensible and even severe difference between being in work or out of work." (2)

In April 1909, Churchill presented the draft Bill to the Cabinet. Employer and State contributions had increased but benefits had decreased and were to be calculated on a stiff sliding-scale over the fifteen weeks so that so that, as Churchill told fellow ministers, "an increasing pressure is put on the recipient of benefit to find work". The Cabinet was divided over the issue. Some like David Lloyd George wanted a more generous and more wide-ranging scheme and he took over responsibility of introducing a national insurance scheme. (3)

In December 1910 Lloyd George sent one of his Treasury civil servants, William J. Braithwaite, to Germany to make an up-to-date study of its State insurance system. On his return he had a meeting with Charles Masterman, Rufus Isaacs and John S. Bradbury. Braithwaite argued strongly that the scheme should be paid for by the individual, the state and the employer: "Working people ought to pay something. It gives them a feeling of self respect and what costs nothing is not valued." (4)

National Insurance

One of the questions that arose during this meeting was whether British national insurance should work, like the German system, on the "dividing-out" principle, or should follow the example of private insurance in accumulating a large reserve. Lloyd George favoured the first method, but Braithwaite fully supported the alternative system. (5) He argued: "If a fund divides out, it is a state club, and not an insurance. It has no continuity - no scientific basis - it lives from day to day. It is all very well when it is young and sickness is low. But as its age increases sickness increases, and the young men can go elsewhere for a cheaper insurance." Lloyd George replied: "Why accumulate a fund? The State could not manage property or invest with wisdom. It would be very bad for politics if the State owned a huge fund." (6)

The debate between the two men continued over the next two months. Lloyd George argued: "The State could not manage property or invest with wisdom. It would be very bad for politics if the State owned a huge fund. The proper course for the Chancellor of the Exchequer was to let money fructify in the pockets of the people and take it only when he wanted it." (7)

Eventually, in March, 1911, Braithwaite produced a detailed paper on the subject, where he explained that the advantage of a state system was the effect of interest on accumulative insurance. Lloyd George told Braithwaite that he had read his paper but admitted he did not understand it and asked him to explain the economics of his health insurance system. (8)

"I managed to convince him that one way or another it (interest) was, and had to be paid. It was at any rate an extra payment which young contributors could properly demand, and the State contribution must at least make it up to them if their contributions were to be taken off and used by the older people. After about half an hour's talk he went upstairs to dress for dinner." Later that night Lloyd George told Braithwaite that he was now convinced by his proposals. "Dividing-out was dead!" (9)

Braithwaite explained that the advantages of an accumulative state fund was the ability to use the insurance reserve to underwrite other social programmes. Lloyd George presented his national insurance proposal to the Cabinet at the beginning of April. "Insurance was to be made compulsory for all regularly employed workers over the age of sixteen and with incomes below the level - £160 a year - of liability for income tax; also for all manual labourers, whatever their income. The rates of contribution would be 4d. a week from a man, and 3d. a week from a woman; 3d. a week from his or her employer; and 2d. a week from the State." (10)

The slogan adopted by Lloyd George to promote the scheme was "9d for 4d". In return for a payment which covered less than half the cost, contributors were entitled to free medical attention, including the cost of medicine. Those workers who contributed were also guaranteed 10s. a week for thirteen weeks of sickness and 5s a week indefinitely for the chronically sick.

Braithwaite later argued that he was impressed by the way Lloyd George developed his policy on health insurance: "Looking back on these three and a half months I am more and more impressed with the Chancellor's curious genius, his capacity to listen, judge if a thing is practicable, deal with the immediate point, deferring all unnecessary decision and keeping every road open till he sees which is really the best. Working for any other man I must inevitably have acquiesced in some scheme which would not have been as good as this one, and I am very glad now that he tore up so many proposals of my own and other people which were put forward as solutions, and which at the time we had persuaded ourselves into thinking possible. It will be an enormous misfortune if this man by any accident should be lost to politics." (11)

David Lloyd George

The large insurance companies were worried that this measure would reduce the popularity of their own private health schemes. David Lloyd George, arranged a meeting with the association that represented the twelve largest companies. Their chief negotiator was Kingsley Wood, who told Lloyd George, that in the past he had been able to muster enough support in the House of Commons to defeat any attempt to introduce a state system of widows' and orphans' benefits and so the government "would be wise to abandon the scheme at once." (12)

David Lloyd George was able to persuade the government to back his proposal of health insurance: "After searching examination, the Cabinet expressed warm and unanimously approval of the main and government principles of the scheme which they believed to be more comprehensive in its scope and more provident and statesmanlike in its machinery than anything that had hitherto been attempted or proposed." (13)

The National Insurance Bill was introduced into the House of Commons on 4th May, 1911. Lloyd George argued: "It is no use shirking the fact that a proportion of workmen with good wages spend them in other ways, and therefore have nothing to spare with which to pay premiums to friendly societies. It has come to my notice, in many of these cases, that the women of the family make most heroic efforts to keep up the premiums to the friendly societies, and the officers of friendly societies, whom I have seen, have amazed me by telling the proportion of premiums of this kind paid by women out of the very wretched allowance given them to keep the household together."

Lloyd George went on to explain: "When a workman falls ill, if he has no provision made for him, he hangs on as long as he can and until he gets very much worse. Then he goes to another doctor (i.e. not to the Poor Law doctor) and runs up a bill, and when he gets well he does his very best to pay that and the other bills. He very often fails to do so. I have met many doctors who have told me that they have hundreds of pounds of bad debts of this kind which they could not think of pressing for payment of, and what really is done now is that hundreds of thousands - I am not sure that I am not right in saying millions - of men, women and children get the services of such doctors. The heads of families get those services at the expense of the food of their children, or at the expense of good-natured doctors."

Lloyd George stated this measure was just the start to government involvement in protecting people from social evils: "I do not pretend that this is a complete remedy. Before you get a complete remedy for these social evils you will have to cut in deeper. But I think it is partly a remedy. I think it does more. It lays bare a good many of those social evils, and forces the State, as a State, to pay attention to them. It does more than that... till the advent of a complete remedy, this scheme does alleviate an immense mass of human suffering, and I am going to appeal, not merely to those who support the Government in this House, but to the House as a whole, to the men of all parties, to assist us." (14)

The Observer welcome the legislation as "by far the largest and best project of social reform ever yet proposed by a nation. It is magnificent in temper and design". (15) The British Medical Journal described the proposed bill as "one of the greatest attempts at social legislation which the present generation has known" and it seemed that it was "destined to have a profound influence on social welfare." (16)

Ramsay MacDonald promised the support of the Labour Party in passing the legislation, but some MPs, including Fred Jowett, George Lansbury and Philip Snowden denounced it as a poll tax on the poor. Along with Keir Hardie, they wanted free sickness and unemployment benefit to be paid for by progressive taxation. Hardie commented that the attitude of the government was "we shall not uproot the cause of poverty, but we will give you a porous plaster to cover the disease that poverty causes." (17)

Lloyd George's reforms were strongly criticised and some Conservatives accused him of being a socialist. There was no doubt that he had been heavily influenced by Fabian Society pamphlets on social reform that had been written by Beatrice Webb, Sidney Webb and George Bernard Shaw. However, some Fabians "feared that the Trade Unions might now be turned into Insurance Societies, and that their leaders would be further distracted from their industrial work." (18)

Lloyd George pointed out that the labour movement in Germany had initially opposed national insurance: "In Germany, the trade union movement was a poor, miserable, wretched thing some years ago. Insurance has done more to teach the working class the virtue of organisation than any single thing. You cannot get a socialist leader in Germany today to do anything to get rid of that Bill... Many socialist leaders in Germany will say that they would rather have our Bill than their own." (19)

Lord Northcliffe and the 1911 National Insurance Act

Alfred Harmsworth, Lord Northcliffe, launched a propaganda campaign against the bill on the grounds that the scheme would be too expensive for small employers. The climax of the campaign was a rally in the Albert Hall on 29th November, 1911. As Lord Northcliffe, controlled 40 per cent of the morning newspaper circulation in Britain, 45 per cent of the evening and 15 per cent of the Sunday circulation, his views on the subject was very important.

H. H. Asquith was very concerned about the impact of the The Daily Mail involvement in this issue: "The Daily Mail has been engineering a particularly unscrupulous campaign on behalf of mistresses and maids and one hears from all constituencies of defections from our party of the small class of employers. There can be no doubt that the Insurance Bill is (to say the least) not an electioneering asset." (20)

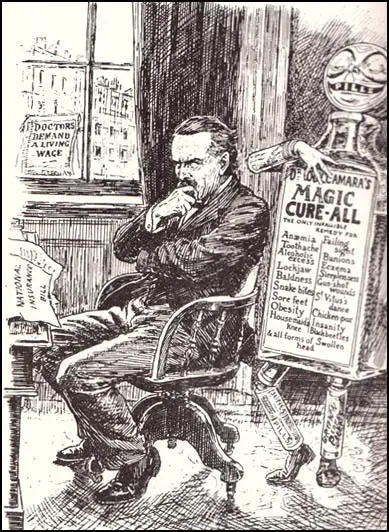

Patent Medicine: "Never mind, dear fellow, I'll stand by you - to the death!"

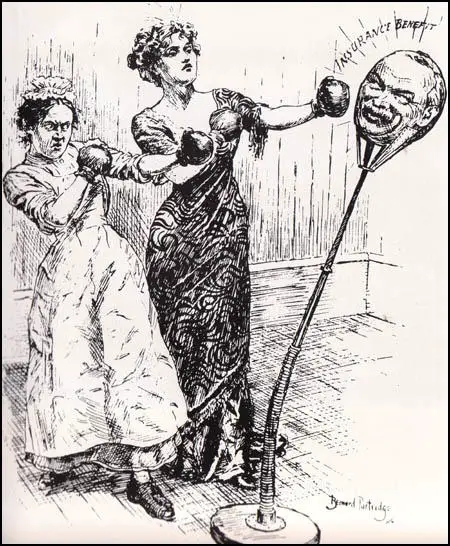

Frank Owen, the author of Tempestuous Journey: Lloyd George and his Life and Times (1954) suggested that it was those who employed servants who were the most hostile to the legislation: "Their tempers were inflamed afresh each morning by Northcliffe's Daily Mail, which alleged that inspectors would invade their drawing-rooms to check if servants' cards were stamped, while it warned the servants that their mistresses would sack them the moment they became liable for sickness benefit." (21)

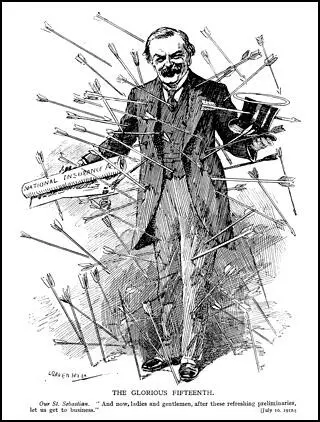

The National Insurance Bill spent 29 days in committee and grew in length and complexity from 87 to 115 clauses. These amendments were the result of pressure from insurance companies, Friendly Societies, the medical profession and the trade unions, which insisted on becoming "approved" administers of the scheme. The bill was passed by the House of Commons on 6th December and received royal assent on 16th December 1911. (22)

Lloyd George admitted that he had severe doubts about the amendments: "I have been beaten sometimes, but I have sometimes beaten off the attack. That is the fortune of war and I am quite ready to take it. Honourable Members are entitled to say that they have wrung considerable concessions out of an obstinate, stubborn, hard-hearted Treasury. They cannot have it all their own way in this world. Let them be satisfied with what they have got. They are entitled to say this is not a perfect Bill, but then this is not a perfect world. Do let them be fair. It is £15,000,000 of money which is not wrung out of the workmen's pockets, but which goes, every penny of it, into the workmen's pocket. Let them bear that in mind. I think they are right in fighting for organisations which have achieved great things for the working classes. I am not at all surprised that they regard them with reverence. I would not do anything which would impair their position. Because in my heart I believe that the Bill will strengthen their power is one of the reasons why I am in favour of this Bill." (23)

The Daily Mail and The Times, both owned by Lord Northcliffe, continued its campaign against the National Insurance Act and urged its readers who were employers not to pay their national health contributions. David Lloyd George asked: "Were there now to be two classes of citizens in the land - one class which could obey the laws if they liked; the other, which must obey whether they liked it or not? Some people seemed to think that the Law was an institution devised for the protection of their property, their lives, their privileges and their sport it was purely a weapon to keep the working classes in order. This Law was to be enforced. But a Law to ensure people against poverty and misery and the breaking-up of home through sickness or unemployment was to be optional." (24)

David Lloyd George attacked the newspaper baron for encouraging people to break the law and compared the issue to the foot-and-mouth plague rampant in the countryside at the time: "Defiance of the law is like the cattle plague. It is very difficult to isolate it and confine it to the farm where it has broken out. Although this defiance of the Insurance Act has broken out first among the Harmsworth herd, it has travelled to the office of The Times. Why? Because they belong to the same cattle farm. The Times, I want you to remember, is just a twopenny-halfpenny edition of The Daily Mail." (25)

Despite the opposition from newspapers and and the British Medical Association, the business of collecting contributions began in July 1912, and the payment of benefits on 15th January 1913. Lloyd George appointed Sir Robert Morant as chief executive of the health insurance system. William J. Braithwaite was made secretary to the joint committee responsible for initial implementation, but his relations with Morant were deeply strained. "Overworked and on the verge of a breakdown, he was persuaded to take a holiday, and on his return he was induced to take the post of special commissioner of income tax in 1913." (26)

Primary Sources

(1) William J. Braithwaite, Lloyd George's Ambulance Wagon (1957)

Looking back on these three and a half months I am more and more impressed with the Chancellor's curious genius, his capacity to listen, judge if a thing is practicable, deal with the immediate point, deferring all unnecessary decision and keeping every road open till he sees which is really the best. Working for any-other man I must inevitably have acquiesced in some scheme which would not have been as good as this one, and I am very glad now that he tore up so many proposals of my own and other people which were put forward as solutions, and which at the time we had persuaded ourselves into thinking possible. It will be an enormous misfortune if this man by any accident should be lost to politics.

(2) David Lloyd George, speech in the House of Commons (4th May, 1911)

It is no use shirking the fact that a proportion of workmen with good wages spend them in other ways, and therefore have nothing to spare with which to pay premiums to friendly societies. It has come to my notice, in many of these cases, that the women of the family make most heroic efforts to keep up the premiums to the friendly societies, and the officers of friendly societies, whom I have seen, have amazed me by telling the proportion of premiums of this kind paid by women out of the very wretched allowance given them to keep the household together...

There is no doubt that there is great reluctance on the part of workmen to resort to the Poor Law medical officer... He has to prove destitution, and although there is a liberal interpretation placed on that by boards of guardians, still it is a humiliation which a man does not care to bear among his neighbours. What generally happens is this. When a workman falls ill, if he has no provision made for him, he hangs on as long as he can and until he gets very much worse. Then he goes to another doctor (i.e. not to the Poor Law doctor) and runs up a bill, and when he gets well he does his very best to pay that and the other bills. He very often fails to do so. I have met many doctors who have told me that they have hundreds of pounds of bad debts of this kind which they could not think of pressing for payment of, and what really is done now is that hundreds of thousands - I am not sure that I am not right in saying millions - of men, women and children get the services of such doctors. The heads of families get those services at the expense of the food of their children, or at the expense of good-natured doctors...

There are forty-three counties and towns in Great Britain with a population of 75,000, and there are 75,000 deaths each year from this disease. If a single one of those counties or towns were devastated by plague so that everybody, man, woman and child, were destroyed there and the place were left desolate, and the same thing happened a second year, I do not think we would wait a single Session to take action. All the resources of this country would be placed at the disposal of science to crush out this disease....

I do not pretend that this is a complete remedy. Before you get a complete remedy for these social evils you will have to cut in deeper. But I think it is partly a remedy. I think it does more. It lays bare a good many of those social evils, and forces the State, as a State, to pay attention to them. It does more than that... till the advent of a complete remedy, this scheme does alleviate an immense mass of human suffering, and I am going to appeal, not merely to those who support the Government in this House, but to the House as a whole, to the men of all parties, to assist us... I appeal to the House of Commons to help the Government not merely to carry this Bill through but to fashion it; to strengthen it where it is weak, to improve it where it is faulty. I am sure if this is done we shall have achieved something which will be worthy of our labours. Here we are in the year of the crowning of the King. We have got men from all parts of this great Empire coming not merely to celebrate the present splendour of the Empire, but also to take counsel together as to the best means of promoting its future welfare. I think that now would be a very opportune moment for us in the Homeland to carry through a measure that will relieve untold misery in myriads of homes - misery that is undeserved; that will help to prevent a good deal of wretchedness, and which will arm the nation to fight until it conquers "the pestilence that walketh in darkness, and the destruction that wasteth at noonday".

(3) Debate in the House of Commons (19th July, 1911)

David Lloyd George: "He is charged 4d. under the State scheme for that benefit. He has, therefore, got a balance of 2d., and he need not pay 2d. in order to get this benefit, or anything like it. That is exactly the point. My own computation is that ½d. would do it, so that his actual gain under this scheme is 3½d. before the deficiency is wiped out. He pays 4d. under the State scheme where he formerly paid 6d. All he has got to do in the future is to pay an extra ½d. to the society, making it 4d. in all, and he gets this double benefit and would still be 3½d. a week better off than he was before....

He gets medical services, maternity benefit, and sanatorium benefit, and if he is over sixteen years of age he gets the benefit of the enormous reserves carried to every trade union and every friendly society. Supposing he wants to insure for the double benefit, all he has to do is to go on with his trade union and pay them ½d. or 1d. a week at the outside, in addition to what he pays the friendly society, so that if he pays 4½d. where he formerly paid 6d. he will get the additional benefits of the scheme, and also the very things members are asking for...

The man earning £1 a week is not - I will not say such a fool - but at such a pass as not to be able to understand it if it is fairly put to him. I think there are members of trade unions who, if you put it to them, that for 4d. a week they are getting 9d. - and again I emphasise the fact - that there is not a penny of that 9d. which the State touches, because the whole expenses of administration by the State is outside that 9d., and he will get the whole of that 9d. for 4d. - if that is told to the working man, he is quite sensible enough to see that when he is offered 9d. for 4d. he is getting a good bargain....

I have been beaten sometimes, but I have sometimes beaten off the attack. That is the fortune of war and I am quite ready to take it. Honourable Members are entitled to say that they have wrung considerable concessions out of an obstinate, stubborn, hard-hearted Treasury. They cannot have it all their own way in this world. Let them be satisfied with what they have got. They are entitled to say this is not a perfect Bill, but then this is not a perfect world. Do let them be fair. It is £15,000,000 of money which is not wrung out of the workmen's pockets, but which goes, every penny of it, into the workmen's pocket. Let them bear that in mind. I think they are right in fighting for organisations which have achieved great things for the working classes. I am not at all surprised that they regard them with reverence. I would not do anything which would impair their position. Because in my heart I believe that the Bill will strengthen their power is one of the reasons why I am in favour of this Bill. In Germany, the trade union movement was a poor, miserable, wretched thing some years ago. Insurance has done more to teach the working classes the value of organisation than any single thing in the whole history of German industrial organisation. I have met several German Labour leaders and Socialist leaders and employers, and they all say the same thing. May I also say another thing. They all state that when the matter was first of all proposed they were all dead against it. They criticised it, even more severely than my Honourable Friends have done this Bill and they regarded it with the same suspicion and apprehension. Their imaginations saw disaster and ruin in it. There is not one of them now who would lift a little finger to get it off the statute book. They have put every muscle into a fight to keep it there. You cannot get a Socialist leader in Germany today to do anything to get rid of that Bill, and I think they will find that many Socialist leaders in Germany will say that they would rather have our Bill than their own Bill. This Bill marks an enormous advance. If Honourable Members reject the Bill it will be a very serious responsibility. I do not think it is one for which the labouring classes would thank them. They are right in fighting for their trade unions. They represent, on the whole, the best stock of the working classes. I would remind them that this Bill benefits the poorer classes and that it will do greater things for them than any Bill introduced for a great many years in this House. It will remove anxiety as to distress, it will heal, it will lift them up, and it will give them a new hope. It will do more than that because it will give them a new weapon which will enable them to organise, and the most valuable and vital thing is that the "working classes will be organised £15,000,000 of them for the first time for their own purposes. Honourable Members can reject this Bill with all these boons, but it is a responsibility I am not prepared to share with them.

Fred Jowett: I do not think that any Member of the party to which I belong will have a single word of complaint to offer as to the tone and spirit of the appeal that has been made to these benches by the right Honourable Gentleman. At the same time I wish to associate myself with other Members on these benches who have spoken against this Clause.... The trade unions do not merely care for their own members, they care also for, and fight the battles of, other workers who are not members of their own unions. In my own town, for instance, the organised representative body to which I belong takes every case, whether the worker belongs to a trade union or not, and fights it under the Compensation Act. I am told that the same thing exists in the constituency of my Honourable Friend the Member for Halifax. There again, not only do the organised trades unions fight cases for their own members, but for other workers as well, and it seems to me a most dangerous tampering with present conditions to bring in this new system of allowing approved societies to jeopardise the harmonious working which at present exists. I think the Chancellor of the Exchequer must admit that for the first time we are, under the guise of giving a new boon to the working classes of this country, taking away part of one that already exists....

Keir Hardie: I think there is one point the Chancellor of the Exchequer did not altogether realise. He, following the lead of my honourable colleague behind me, appealed to the Labour party not to take the responsibility of wrecking this Bill, but he forgets that the last word does not rest with us. We are here as representatives. I am sure the Chancellor of the Exchequer will agree that in trying to get concessions we have not unduly or in any raucous spirit criticised the Bill either in the House of Commons or outside. Individuals may have done so, but individual Liberals have done the same....

What I was going to say was that we have endeavoured to-smooth the way amongst the working classes for the passage of this Bill, but there is a large element among us who regard many of these details with distrust - I am not speaking of Socialists, but of trade unionists. All among us bring the tale that whilst everyone desires some kind of scheme like the present, they are distrustful of many of its details, and when this Clause gets to be understood, that distrust will certainly be deep....

Desiring, as I do, to see the Bill go through, if there was no alternative but to reduce the sick pay in order to get rid of this Clause, speaking for myself, I believe that would be a lesser evil. A second point is this: the last part of this Clause has a distinct tendency to weaken the trade union movement. I know that is not the intention of the Chancellor of the Exchequer. One of the strong reasons which now exists to induce workmen to join trade unions is the securing of a medium whereby compensation will be secured to them when accidents occur. Propaganda speeches are always taken up in part in showing the amount of compensation which the union has obtained for its members, and showing also that where there is no union the employers are apt to force a smaller scale on the men who are injured. If this Clause goes through that argument is taken away from the trade unions because the committee of the society which is their benefit society will be able to act for them - in fact is compelled to act for them.

(4) David Lloyd George, speech at Woodford (29th June, 1912)

The Insurance Act will come into operation on July the fifteenth. I wish to make an appeal for a fair trial for the Act from the people in this country. There are those who forget that it is an Act of Parliament. In this and in every other country there are bad tempered people who want their own way; if they don't get it, they smash something. When these people lose their tempers they try to punish somebody; and, if they cannot punish the people responsible for the law that they do not like, they punish somebody who is near to them, somebody who is helpless, somebody who has served them faithfully. They cannot get at me, and they cannot turn the Prime Minister out; so they begin worrying the servants. They write letters to the papers threatening to reduce the wages of their servants, threatening to lengthen their hours - I should have thought that almost impossible - and, in the end, threatening to dismiss them.

They are always dismissing servants. Whenever any Liberal Act of Parliament is passed, they dismiss them. I wonder that they have any servants left. Sir William Harcourt imposed death duties; they dismissed servants. I put on a super-tax; they dismissed more. Now the Insurance Act comes, and the last of them, I suppose, will have to go. You will be having, on the swell West End houses, notices like "not at home - her ladyship's washing day".

(5) Frank Owen, Tempestuous Journey: Lloyd George and his Life and Times (1954)

The housewives who kept servants were more hostile still. Their tempers were inflamed afresh each morning by Northcliffe's Daily Mail, which alleged that inspectors would invade their drawing-rooms to check if servants' cards were stamped, while it warned the servants that their mistresses would sack them the moment they became liable for sickness benefit...

Later, when Northcliffe pursued his campaign in his latest acquisition, The Times, and advised his new public not to observe the Act, Lloyd George took on a different tone. Were there now to be two classes of citizens in the land - one class which could obey the laws if they liked; the other, which must obey whether they liked it or not? Some people seemed to think that the Law was an institution devised for the protection of their property, their lives, their privileges and their sport it was purely a weapon to keep the working classes in order. This Law was to be enforced. But a Law to ensure people against poverty and misery and the breaking-up of home through sickness or unemployment was to be optional. Was the Law for the preservation of game to be optional? Was the payment of rent to be optional?

Student Activities

1832 Reform Act and the House of Lords (Answer Commentary)

The Chartists (Answer Commentary)

Women and the Chartist Movement (Answer Commentary)

Benjamin Disraeli and the 1867 Reform Act (Answer Commentary)

William Gladstone and the 1884 Reform Act (Answer Commentary)

Richard Arkwright and the Factory System (Answer Commentary)

Robert Owen and New Lanark (Answer Commentary)

James Watt and Steam Power (Answer Commentary)

Road Transport and the Industrial Revolution (Answer Commentary)

Canal Mania (Answer Commentary)

Early Development of the Railways (Answer Commentary)

The Domestic System (Answer Commentary)

The Luddites: 1775-1825 (Answer Commentary)

The Plight of the Handloom Weavers (Answer Commentary)

Health Problems in Industrial Towns (Answer Commentary)

Public Health Reform in the 19th century (Answer Commentary)

Walter Tull: Britain's First Black Officer (Answer Commentary)

Football and the First World War (Answer Commentary)

Football on the Western Front (Answer Commentary)

Käthe Kollwitz: German Artist in the First World War (Answer Commentary)

American Artists and the First World War (Answer Commentary)