William J. Braithwaite

William John Braithwaite, the second son of the Revd Francis Joseph Braithwaite, and his wife, Mary Hopkinson Braithwaite, was born at the rectory, Great Waldingfield, Suffolk, on 1st June 1875. He was educated at Winchester College and at New College, where he held a scholarship and won first classes in classical moderations (1896) and literae humaniores (1898). (1)

After leaving University of Oxford he came sixth in the civil-service examinations in 1898 and entered the Inland Revenue. He went to live at Toynbee Hall in the East End of London and "for the rest of his life took an enthusiastic interest in boys' clubs and the provision of playing fields." (2)

Braithwaite married Lilian Duncan on 2nd June 1908, with whom he had one son and one daughter. In 1909, he worked with David Lloyd George on the People's Budget. He also conducted an inquiry on behalf of the Liberal government into local income taxes in Switzerland and Germany in 1910. (3)

William Braithwaite & David Lloyd George

In December 1910 Lloyd George sent Braithwaite to Germany to make an up-to-date study of its State insurance system. On his return he had a meeting with Charles Masterman, Rufus Isaacs and John S. Bradbury. Braithwaite argued strongly that the scheme should be paid for by the individual, the state and the employer: "Working people ought to pay something. It gives them a feeling of self respect and what costs nothing is not valued." (4)

One of the questions that arose during this meeting was whether British national insurance should work, like the German system, on the "dividing-out" principle, or should follow the example of private insurance in accumulating a large reserve. Lloyd George favoured the first method, but Braithwaite fully supported the alternative system. (5) He argued: "If a fund divides out, it is a state club, and not an insurance. It has no continuity - no scientific basis - it lives from day to day. It is all very well when it is young and sickness is low. But as its age increases sickness increases, and the young men can go elsewhere for a cheaper insurance." Lloyd George replied: "Why accumulate a fund? The State could not manage property or invest with wisdom. It would be very bad for politics if the State owned a huge fund." (6)

The debate between the two men continued over the next two months. Lloyd George argued: "The State could not manage property or invest with wisdom. It would be very bad for politics if the State owned a huge fund. The proper course for the Chancellor of the Exchequer was to let money fructify in the pockets of the people and take it only when he wanted it." (7)

Eventually, in March, 1911, Braithwaite produced a detailed paper on the subject, where he explained that the advantage of a state system was the effect of interest on accumulative insurance. Lloyd George told Braithwaite that he had read his paper but admitted he did not understand it and asked him to explain the economics of his health insurance system. (8)

"I managed to convince him that one way or another it (interest) was, and had to be paid. It was at any rate an extra payment which young contributors could properly demand, and the State contribution must at least make it up to them if their contributions were to be taken off and used by the older people. After about half an hour's talk he went upstairs to dress for dinner." Later that night Lloyd George told Braithwaite that he was now convinced by his proposals. "Dividing-out was dead!" (9)

Braithwaite explained that the advantages of an accumulative state fund was the ability to use the insurance reserve to underwrite other social programmes. Lloyd George presented his national insurance proposal to the Cabinet at the beginning of April. "Insurance was to be made compulsory for all regularly employed workers over the age of sixteen and with incomes below the level - £160 a year - of liability for income tax; also for all manual labourers, whatever their income. The rates of contribution would be 4d. a week from a man, and 3d. a week from a woman; 3d. a week from his or her employer; and 2d. a week from the State." (10)

1911 National Insurance Act

The slogan adopted by David Lloyd George to promote the scheme was "9d for 4d". In return for a payment which covered less than half the cost, contributors were entitled to free medical attention, including the cost of medicine. Those workers who contributed were also guaranteed 10s. a week for thirteen weeks of sickness and 5s a week indefinitely for the chronically sick.

Braithwaite later argued that he was impressed by the way Lloyd George developed his policy on health insurance: "Looking back on these three and a half months I am more and more impressed with the Chancellor's curious genius, his capacity to listen, judge if a thing is practicable, deal with the immediate point, deferring all unnecessary decision and keeping every road open till he sees which is really the best. Working for any other man I must inevitably have acquiesced in some scheme which would not have been as good as this one, and I am very glad now that he tore up so many proposals of my own and other people which were put forward as solutions, and which at the time we had persuaded ourselves into thinking possible. It will be an enormous misfortune if this man by any accident should be lost to politics." (11)

Braithwaite also claims that Lloyd George introduced him to colleagues as his principal helper. However, others have questioned this: "It never seems to have occurred to him that such phrases were doubtless used about other helpers when it was convenient to flatter them and when Braithwaite was not there to hear. Pathetically Braithwaite took them as considered judgments." (12)

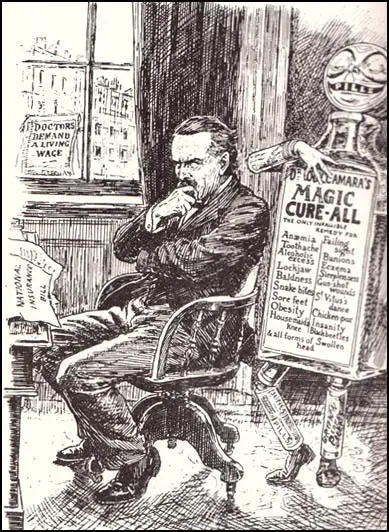

Patent Medicine: "Never mind, dear fellow, I'll stand by you - to the death!"

The National Insurance Bill spent 29 days in committee and grew in length and complexity from 87 to 115 clauses. These amendments were the result of pressure from insurance companies, Friendly Societies, the medical profession and the trade unions, which insisted on becoming "approved" administers of the scheme. The bill was passed by the House of Commons on 6th December and received royal assent on 16th December 1911. (13)

Civil Servant

Despite the opposition from newspapers and and the British Medical Association, the business of collecting contributions began in July 1912, and the payment of benefits on 15th January 1913. David Lloyd George appointed Sir Robert Morant as chief executive of the health insurance system. William Braithwaite was made secretary to the joint committee responsible for initial implementation, but his relations with Morant were deeply strained. "Overworked and on the verge of a breakdown, he was persuaded to take a holiday, and on his return he was induced to take the post of special commissioner of income tax in 1913." (14)

Lloyd George has been criticised for not appointing Braithwaite as the chief executive of the health insurance system. John Grigg has argued that Lloyd George was fully justified in making this decision. "Since he (Braithwaite) was a fairly junior member of the official hierarchy, his appointment to such a responsible position would have been resented by many of his seniors and contemporaries at the Treasury, whose goodwill was needed by the Commission." (15)

Christopher Hollis believes that the main reason that Morant got the job was that he had the support of Beatrice Webb, Sidney Webb and other senior members of the Fabian Society: "Human nature being what it is, it was perhaps natural that Braithwaite should have felt grievance at first when he did not get the job on which he had set his heart, nor do we find it difficult to believe that thaj job was given to Morant for reasons of political convenience - to keep quiet the Webbs". (16)

It has been claimed that Braithwaite "was rather slow in his speech and paternal in manner but overall amiable and well liked". According to one friend "had an immense capacity for work, marked organizing ability, and possessed in a high degree the quality of carrying through to a finish any task he had begun". (17) Another source suggests he "was idealistic to a fault, with a high-mindedness sometimes verging on self-righteousness". (18)

William Braithwaite retired in 1937 but unfortunately died while on holiday on 14th March 1938. His autobiography, Lloyd George's Ambulance Wagon, was published in 1957.

Primary Sources

(1) William J. Braithwaite, Lloyd George's Ambulance Wagon (1957)

Looking back on these three and a half months I am more and more impressed with the Chancellor's curious genius, his capacity to listen, judge if a thing is practicable, deal with the immediate point, deferring all unnecessary decision and keeping every road open till he sees which is really the best. Working for any-other man I must inevitably have acquiesced in some scheme which would not have been as good as this one, and I am very glad now that he tore up so many proposals of my own and other people which were put forward as solutions, and which at the time we had persuaded ourselves into thinking possible. It will be an enormous misfortune if this man by any accident should be lost to politics.

(2) Christopher Hollis, The Spectator (5th September, 1957)

William J. Braithwaite.... was a high-minded civil servant who was employed by Lloyd George to help him draft the National Health Insurance Act of 1912. It is clear from the story that Braithwaite did a great deal of work during that and the previous years. It is not clear how his contribution was to be compared with that of other helpers. With some naiveté he quotes as evidence certain remarks of Lloyd George in which Lloyd George introduced him to colleagues as his principal helper. It never seems to have occurred to him that such phrases were doubtless used about other helpers when it was convenient to flatter them and when Braithwaite was not there to hear. Pathetically Braithwaite took them as considered judgments and confidently expected that as a reward he would be entrusted with the administration of the Act. He was bitterly disappointed when that task was entrusted to Sir Robert Morant, whom he detested (he himself was fobbed off with a secretaryship), and still more disappointed when shortly afterwards he was transferred to the Inland Revenue, where he spent the rest of his days.

Human nature being what it is, it was perhaps natural that Braithwaite should have felt grievance at first when he did not get the job on which he had set his heart, nor do we find it difficult to believe that thaj job was given to Morant for reasons of political convenience - to keep quiet the Webbs. But the list of men who were first flattered and then let down by Lloyd George is of so enormous a length that it is indeed odd that Braithwaite should imagine that there would be an interest in the story twenty-five years later and odder still that the editor should think that the public will still be interested today. It is as if a man were to write a book to explain how fifty-three years ago he was once caught in the rain.

(3) Jonathan Bradbury, William Braithwaite : Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004-2014)

The high point of Braithwaite's career was his work on the national health insurance scheme which formed part 1 of the National Insurance Act of 1911. The scheme instigated the first state-organized programme to provide for the health needs of a workforce vastly changed by nineteenth-century industrialization and urbanization. A large part of the workforce was compelled to pay regular contributions into an insurance fund. These contributions were matched by employers and the Treasury to underpin a fund which could pay out a range of health benefits on sickness, disablement, medical treatment, maternity care, and sanatorium attendance. As a former resident (1898–1903) at Toynbee Hall, the university settlement in the East End of London, Braithwaite had, like his friend and near contemporary, William Beveridge, a familiarity with social problems. He was picked by Lloyd George, then chancellor of the exchequer, to go to Germany to carry out the initial investigation of how social insurance schemes operated there. In November 1910 he became Lloyd George's principal assistant in devising the detail of a scheme for Britain. His skills assisted Lloyd George in developing practicable working arrangements in which approved insurance societies were retained as the main local administrative agents. He also bolstered the chancellor in pressing on with the reform despite a lack of clear support from elsewhere within either the government or the civil service.

Student Activities

1832 Reform Act and the House of Lords (Answer Commentary)

The Chartists (Answer Commentary)

Women and the Chartist Movement (Answer Commentary)

Benjamin Disraeli and the 1867 Reform Act (Answer Commentary)

William Gladstone and the 1884 Reform Act (Answer Commentary)

Richard Arkwright and the Factory System (Answer Commentary)

Robert Owen and New Lanark (Answer Commentary)

James Watt and Steam Power (Answer Commentary)

Road Transport and the Industrial Revolution (Answer Commentary)

Canal Mania (Answer Commentary)

Early Development of the Railways (Answer Commentary)

The Domestic System (Answer Commentary)

The Luddites: 1775-1825 (Answer Commentary)

The Plight of the Handloom Weavers (Answer Commentary)

Health Problems in Industrial Towns (Answer Commentary)

Public Health Reform in the 19th century (Answer Commentary)

Walter Tull: Britain's First Black Officer (Answer Commentary)

Football and the First World War (Answer Commentary)

Football on the Western Front (Answer Commentary)

Käthe Kollwitz: German Artist in the First World War (Answer Commentary)

American Artists and the First World War (Answer Commentary)