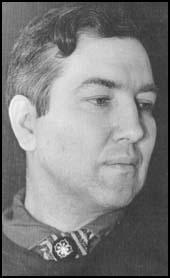

Robert Graves

Robert von Ranke Graves, the son of Alfred Graves, an inspector of schools, and Amalie von Ranke, was born at Red Branch House, Lauriston Road, Wimbledon, on 24th July, 1895. His father was also the editor of an Irish literary magazine and a published poet.

At thirteen Graves was sent to Charterhouse public school where he was bullied. Graves later wrote how "the legend was put about that I was not only German but a German-Jew." He also became close to a much younger boy, Peter Johnstone: "In English preparatory and public schools romance is necessarily homosexual. The opposite sex is despised and treated as something obscene. Many boys never recover from this perversion. For every one born homosexual, at least ten permanent pseudo-homosexuals are made by the public school system: nine of these ten as honourably chaste and sentimental as I was."

Graves developed a good relationship with George Mallory, encouraging his interest in poetry and mountaineering. Graves later recalled: "He (Mallory) was wasted at Charterhouse. He tried to treat his class in a friendly way, which puzzled and offended them." Richard Perceval Graves added: "Graves's earliest Carthusian verse, though technically imperfect, is highly forceful, reflecting as it does the desperately overwrought condition into which he had been plunged by the assiduous bullying of those who resented him, chiefly because he was trying to live up to the high moral standards of his home. Under the protective tutelage of George Mallory, with whom he went rock-climbing, poetry became not merely an escape, but a positive pleasure."

Graves won a classical exhibition at St John's College. Although a convinced pacifist, Graves was so shocked by the German invasion of Belgium on 4th August 1914, that joining up seemed to him the only honourable course of action. Granted a commission in the Royal Welch Fusiliers, Captain Graves served on the Western Front where he met the poet, Siegfried Sassoon, and the two men became close friends and discussed the possibility of living together after the war.

Graves was traumatized by his experiences in the First World War. Later he recorded the death of a popular officer: "Sampson lay groaning about twenty yards beyond the front trench. Several attempts were made to rescue him. He was badly hit. Three men got killed in these attempts: two officers and two men, wounded. In the end his own orderly managed to crawl out to him. Sampson waved him back, saying he was riddled through and not worth rescuing; he sent his apologies to the company for making such a noise. At dusk we all went out to get the wounded, leaving only sentries in the line. The first dead body I came across was Sampson. He had been hit in seventeen places. I found that he had forced his knuckles into his mouth to stop himself crying out and attracting any more men to their death."

Like many young officers, Graves believed that the only way to survive the war was to get wounded: "I went on patrol fairly often, finding that the only thing respected in young officers was personal courage. Besides, I had cannily worked it out like this. My best way of lasting through to the end of the war would be to get wounded. The best time to get wounded would be at night and in the open, with rifle fire more or less unaimed and my whole body exposed. Best, also, to get wounded when there was no rush on the dressing-station services, and while the back areas were not being heavily shelled. Best to get wounded, therefore, on a night patrol in a quiet sector. One could usually manage to crawl into a shell hole until help arrived."

In July 1916 he was seriously wounded when shrapnel from an exploding shell pierced his chest and thigh. The army mistakenly informed Alfred Graves that his son had been killed and even forwarded the family his personal belongings. His obituary was published in The Times before it was realised that he was still alive. After recovering from his wounds he returned to the front-line. During this period he published two collections of poetry, Over the Brazier (1916) and Fairies and Fusiliers (1917).

In 1917 Graves was hospitalized with shell-shock. While on leave he met up with Siegfried Sassoon who was also recovering from wounds suffered in France. Sassoon, like Graves, had grown increasingly angry about the tactics being employed by the British Army and after a meeting with Bertrand Russell, John Murry Middleton and H. W. Massingham, he wrote Finished With War: A Soldier's Declaration, which announced that "I am making this statement as an act of wilful defiance of military authority because I believe that the war is being deliberately prolonged by those who have the power to end it. I am a soldier, convinced that I am acting on behalf of soldiers. I believe that the war upon which I entered as a war of defence and liberation has now become a war of aggression and conquest. I believe that the purposes for which I and my fellow soldiers entered upon this war should have been so clearly stated as to have made it impossible to change them and that had this been done the objects which actuated us would now be attainable by negotiation." In July 1917 Sassoon arranged for a sympathetic Labour Party MP to read out the statement in the House of Commons. Instead of the expected court martial, the under-secretary for war declared him to be suffering from shell-shock, and he was sent to Craiglockhart War Hospital, near Edinburgh.

While he was on leave he fell in love with Nancy Nicholson, the sister of the artist Ben Nicholson. They were married on 23rd January 1918; and after Graves's demobilization they moved into Dingle Cottage in the garden of John Masefield on Boars Hill near Oxford. Over the next five years Nancy gave birth to four children. Graves studied English literature at St John's College during this period. Graves continued to write poetry but was severly distressed by the poor reception given in 1920 to Country Sentiment.

In 1925 Graves was appointed professor of English literature at Cairo University. He set sail for Egypt in January 1926 not only with his wife and family but also with the young American poet Laura Riding. Together they would write the ground-breaking Survey of Modernist Poetry (1927) and helped him prepare his Poems: 1914-26 (1927). Richard Perceval Graves has argued: "After a bizarre period during which the ménage à trois between Robert Graves, Nancy, and Laura became a ménage à quatre with the Irish poet Geoffrey Phibbs (a period which ended only when Laura attempted suicide by hurling herself from the window of 35A St Peter's Square, London), Laura rescued Graves both from his failing marriage and from the moral censure of his wider family. She also acted as intellectual and spiritual midwife."

Riding also encouraged Graves to write his memoirs of the First World War. The book, Goodbye to All That, was published to critical acclaim in 1929. Later that year Graves and Laura moved to Deyá, Majorca, where they lived and worked together. With the help of Riding he wrote two extremely successful historical novels, I Claudius (1934) and Claudius the God (1934). This period also saw the publication of two more collections of poems: Poems: 1926-1930 (1931) and Collected Poems (1938).

In 1939 Laura Riding left Graves for Schuyler Jackson. Graves returned to England alone, and was saved from a mental breakdown only by the love of Beryl Hodge and the wife of Alan Hodge. Beryl, who had long admired Robert, became his new muse and mistress and in 1940 they set up house in Devon, where they stayed during the Second World War. Over the next few years he published a large number of works including The Story of Mary Powell (1943), The Golden Fleece (1945) and King Jesus (1946).

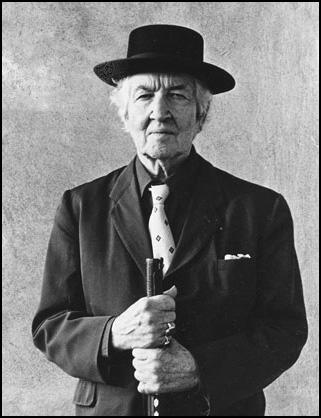

In 1946 Graves moved to Mallorca where he wrote The Greek Myths (1955), The Crowning Privilege (1955) and The Hebrew Myths (1964), Between 1961 and 1966 Graves was Professor of Poetry at Oxford University. He was also offered the CBE, which he declined as he did not agree with the British honours system.

Robert Graves died in Deya on 7th December 1985.

The First World War (3,250 pages - £4.95)

Primary Sources

(1) In his autobiography, Goodbye to All That, Robert Graves wrote about his time at Charterhouse.

In English preparatory and public schools romance is necessarily homosexual. The opposite sex is despised and treated as something obscene. Many boys never recover from this perversion. For every one born homosexual, at least ten permanent pseudo-homosexuals are made by the public school system: nine of these ten as honourably chaste and sentimental as I was.

In the second term the trouble began. A number of things naturally made for my unpopularity. Besides being a scholar and not outstandingly good at games, I was always short of pocket-money. Since I could not conform to the social custom of treating my contemporaries to tuck at the school shop, I could not accept their treating. My clothes, though conforming outwardly to the school pattern, were ready-made and not of the best-quality cloth that all the other boys wore.

The most unfortunate disability of all was that my name appeared on the school list as 'R. von R. Graves'. I had hitherto believed my second name to be 'Ranke'; the 'von', encountered on my birth certificate, disconcerted me. Carthusians behaved secretively about their second names, and usually managed to conceal fancy ones. I could no doubt have passed off' Ranke', without the' von', as monosyllabic and English, but 'von Ranke' was glaring. Businessmen's sons, at this time, used to discuss hotly the threat, and even the necessity, of a trade war with the Reich. 'German' meant 'dirty German'. It meant: 'cheap, shoddy goods competing with our sterling industries.' It also meant military menace, Prussianism, useless philosophy, tedious scholarship, loving music and sabre-rattling.

One of my last recollections at Charterhouse is a school debate on the motion 'that this House is in favour of compulsory military service'. The Empire Service League, with Earl Roberts of Kandahar, V.C., as its President, sent down apropagandist in support. Only six votes out of one hundred and nineteen were noes. I was the principal opposition speaker, having recently resigned from the Officers' Training Corps in revolt against the theory of implicit obedience to orders. And during a fortnight spent the previous summer at the O.T.C. camp near Tidworth on Salisbury Plain, I had been frightened by a special display of the latest military fortifications: barbed-wire entanglements, machine-guns, and field artillery in action. General, now Field-Marshal Sir William Robertson, who had a son at the school, visited the camp and impressed upon us that war with Germany must inevitably break out within two or three years, and that we must be prepared to take our part in it as leaders of the new forces which would assuredly be called into being. Of the six noes,

Nevill Barbour and I are, I believe, the only ones who survived the war.

(2) Robert Graves, Goodbye to All That (1929)

I had just finished at Charterhouse and gone up to Harlech, when England declared war on Germany. A day or two later I decided to enlist. In the first place, though the papers predicted only a very short war - over by Christmas at the outside - I hoped that it might last long enough to delay my going to Oxford in October, which I dreaded. Nor did I work out the possibilities of getting actively engaged in the fighting, expecting garrison service at home, while the regular forces were away. In the second place, I was outraged to read of the Germans' cynical violation of Belgian neutrality.

(3) Robert Graves, Goodbye to All That (1929)

Dunn showed me around the line. The battalion frontage was about eight hundred yards. Each company held some two hundred of these, with two platoons in the front line, and two in the support line about a hundred yards back. He introduced me to the platoon sergeants, more particularly to Sergeant Eastmond and told him to give me any information I wanted; then went back to sleep, asking to be woken at once if anything went wrong. I found myself in charge of the line. Sergeant Eastmond being busy with a working-party.

I went round by myself. The men of the working-party, whose job was to replace the traverses, or safety-buttresses, of the trench, looked curiously at me. They were filling sandbags with earth, piling them up bricklayer fashion, the headers and stretchers alternating, then patting them flat with spades. The sentries stood on the fire-step at the comers of the traverses, stamping their feet and blowing on their fingers. Every now and then they peered over the top for a few seconds. Two parties, each of an N.C.O. and two men, were out in the company listening-posts, connected with the front trench by a sap about fifty yards long. The German front line stretched some three hundred yards beyond. From berths hollowed in the sides of the trench and curtained with sandbags came the grunt of sleeping me.

I jumped up on the fire-step beside the sentry and cautiously raised my head, staring over the parapet. I could see nothing except the wooden pickets supporting our protecting barbed-wire entanglements, and a dark patch or two of bushes beyond. The darkness seemed to move and shake about as I looked at it; the bushes started travelling, singly at first, then both together. The pickets did the same. I was glad of the sentry beside me; he gave his name as Beaumont. 'They're quiet tonight, sir,' he said.

I said: It's funny how those bushes seem to move.'

'Aye, they do play queer tricks. Is this your first spell in trenches?"

A German flare shot up, broke into bright flame, dropped slowly and went hissing into the grass just behind our trench, showing up the bushes and pickets. Instinctively I moved.

'It's bad to do that, sir,' he said, as a rifle-bullet cracked and seemed to pass right between us. 'Keep still, sir, and they can't spot you. Not but what a flare is a bad thing to fall on you. I've seen them burn a hole in a man.'

(4) In his book Goodbye to All That, Robert Graves wrote about what happened when a popular officer was wounded in No Mans Land.

Sampson lay groaning about twenty yards beyond the front trench. Several attempts were made to rescue him. He was badly hit. Three men got killed in these attempts: two officers and two men, wounded. In the end his own orderly managed to crawl out to him. Sampson waved him back, saying he was riddled through and not worth rescuing; he sent his apologies to the company for making such a noise. At dusk we all went out to get the wounded, leaving only sentries in the line. The first dead body I came across was Sampson. He had been hit in seventeen places. I found that he had forced his knuckles into his mouth to stop himself crying out and attracting any more men to their death.

(5) Robert Graves, The Leveller, (1916)

Near Martinpuich that night of hell

Two men were struck by the same shell,

Together tumbling in one heap

Senseless and limp like slaughtered sheep.

One was a pale eighteen-year-old,

Blue-eyed and thin and not too bold,

Pressed for the war not ten years too soon,

The shame and pity of his platoon.

The other came from far-off lands

With brisling chin and whiskered hands,

He had known death and hell before

In Mexico and Ecuador.

Yet in his death this cut-throat wild

Groaned 'Mother! Mother!' like a child,

While the poor innocent in man's clothes

Died cursing God with brutal oaths.

Old Sergeant Smith, kindest of men,

Wrote out two copies and then

Of his accustomed funeral speech

To cheer the womanfolk of each:-

"He died a hero's death: and we

His comrades of 'A' Company

Deeply regret his death: we shall

All deeply miss so true a pal."

(6) Robert Graves, Goodbye to All That (1929)

My first night Captain Thomas asked whether I would like to go out on patrol. It was the regimental custom to test new officers in this way, and none dared excuse himself. My orders for this patrol were to see whether a certain German sap-head was occupied by night or not.

Sergeant Townsend and I went out from Red Lamp Comer at about ten o clock; both carrying revolvers. We had pulled socks with the toes cut off, over our bare knees, to prevent them showing up in the dark and to make crawling easier. We went ten yards at a time, slowly, not on all fours, but wriggling flat along the ground. After each movement we lay and watched for about ten minutes. We crawled through our own wire entanglements and along a dry ditch; ripping our clothes on more barbed-wire, glaring into the darkness until it began turning round and round. Once I snatched my fingers in horror from where I had planted them on the slimy body of an old corpse. We nudged each other with rapidly beating hearts at the slightest noise or suspicion: crawling, watching, crawling, shamming dead under the blinding light of enemy flares, and again crawling watching, crawling.

We found the gap in the German wire and at last came within five yards of the sap-head. We waited quite twenty minutes, listening for any signs of its occupation. Then I nudged Sergeant Townsend and, revolver in hand, we wriggled quickly forward and slid into it. It was about three feet deep and unoccupied. On the floor were a few empty cartridges, and a wicker basket containing something large and smooth and round, twice the size of a football. Very, very carefully I groped and felt all around it in the dark. I was afraid that it might be some sort of infernal machine. Eventually I dared lift it out and carry it back, suspecting that it might be one of the German gas-cylinders we had heard so much about.

After this I went on patrol fairly often, finding that the only thing respected in young officers was personal courage. Besides, I had cannily worked it out like this. My best way of lasting through to the end of the war would be to get wounded. The best time to get wounded would be at night and in the open, with rifle fire more or less unaimed and my whole body exposed. Best, also, to get wounded when there was no rush on the dressing-station services, and while the back areas were not being heavily shelled. Best to get wounded, therefore, on a night patrol in a quiet sector. One could usually manage to crawl into a shell hole until help arrived.

(7) Robert Graves, Goodbye to All That (1929)

Having now been in the trenches for five months, I had passed my prime. For the first three weeks, an officer was of little use in the front line; he did not know his way about, had not learned the rules of health and safety, or grown accustomed to recognizing degrees of danger. Between three weeks and four weeks he was at his best, unless he happened to have any particular bad shock or sequence of shocks. Then his usefulness gradually declined as neurasthenia developed. At six months he was still more or less all right; but by nine or ten months, unless he had been given a few weeks' rest on a technical course, or in hospital, he usually became a drag on the other company officers. After a year or fifteen months he was often worse than useless. Dr W. H. R. Rivers told me later that the action of one of the ductless glands - I think the thyroid - caused this slow general decline in military usefulness, by failing at a certain point to pump its sedative chemical into the blood. Without its continued assistance A man went about his tasks in an apathetic and doped condition, cheated into further endurance. It has taken some ten years for my blood to recover.

Officers had a less laborious but a more nervous time than the men. There were proportionately twice as many neurasthenic cases among officers as among men, though a man's average expectancy of trench service before getting killed or wounded was twice as long as an officer's. Officers between me ages of twenty-three and thirty-three could count on a longer useful life than those older or younger. I was too young. Men over forty, though not suffering from want of sleep so much as those under twenty, had less resistance to sudden alarms and shocks. The unfortunates were officers who had endured two years or more of continuous trench service. In many cases they became dipsomaniacs. I knew three or four who had worked up to the point of two bottles of whisky a day before being lucky enough to get wounded or sent home in some other way. A two-bottle company commander of one of our line battalions is still alive who, in three shows running, got his company needlessly destroyed because he was no longer capable of taking clear decisions.

(8) Robert Graves wrote about his experiences of the First World War in his autobiography, Goodbye to All That. This passage refers to an attack where the battalion suffered very heavy casualties. Only three junior officers, Choate, Henry and Hill survived.

Hill told me the story. The Colonel and Adjutant were sitting down to a meat pie when Hill arrived. Henry said: "Come to report, sir. Ourselves and about ninety men of all companies."

They looked up. "So you have survived, have you?" the Colonel said. "Well all the rest are dead. I suppose Mr. Choate had better command what's left of 'A'. The bombing officer (he had not gone over, but remained at headquarters) will command what's left of 'B'. Mr. Henry goes to 'C' Company. Mr. Hill to 'D'. Let me know where to find you if you are needed. Good night."

Not having being offered a piece of meat pie or a drink of whisky, they saluted and went miserably out. The Adjutant called them back, Mr. Hill, Mr. Henry."

Hill said he expected a change of mind of mind as to the propriety with which hospitality could be offered by a regular Colonel and Adjutant to a temporary second lieutenant in distress. But it was only: "Mr. Hill, Mr. Henry, I saw some men in the trench just now with their shoulder-straps unbuttoned. See that this does not occur in future."

(9) Letter from Lieutenant Colonel Crawshay informing Robert Graves's parents of their son's death on 22nd July 1916.

I very much regret to have to write and tell you your son has died of wounds. He was very gallant, and was doing so well and is a great loss. He was hit by a shell and very badly wounded, and died on the way down to the base I believe. He was not in bad pain, and our doctor managed to get across and attend to him at once.

We have had a very hard time, and our casualties have been large. Believe me you have all our sympathy in your loss, and we have lost a very gallant soldier. Please write to me if I can tell you or do anything.

(10) Paul O'Prey, Robert Graves and Literary Survival (2007)

Graves’s first book of poems was published while he was in France, in 1916. This was mainly a collection of poems about the war, and was received with some surprise by readers and fellow poets. The anonymous reviewer in the TLS noted their "compelling rawness and … blunt familiarity", and admired the "arresting sense of the realities of trench life". The poems were tame compared to what Graves, Owen, Sassoon and others of their circle went on to write, but the review shows Graves was one of the first to attempt to write in a way about the war which tried to capture the extremeness of the experience. Indeed, Siegfried Sassoon, a fellow officer in Graves’s regiment and one of his closest friends during the war, thought Graves’s early poems about the war "violent and repulsive".

As the war progressed, poets such as Sassoon and Owen developed a more overtly political aesthetic, and saw poetry as a weapon to be deployed against the civilian and military attitudes which endorsed the continuation of hostilities against Germany. Somewhat typically, Graves was by this time doing something different, using his poetry in a more personal quest for survival. The majority of the poems he wrote in 1917 while sitting in trenches and dugouts along the Somme, were not about the horrors of trench life, but about childhood innocence and the English and Welsh countryside. He appeared to use his poetry to protect himself from being overwhelmed by the war by writing about situations and images that were emblematic of peace. To Sassoon, this now looked like escapism and the dereliction of his duty as a war poet.

Graves’s feelings about the war were more complex and ambiguous than Sassoon’s, and his writings reflect this. For modern readers in particular, he can be unfashionably positive about soldiering and enthusiastic about bravery. His best war poems are celebratory of the bond of friendship and solidarity that grew to exist between those caught in the fighting, and which sustained him emotionally during his time at the front and after.

The reception of Graves as a war poet changed radically from 1918, when he was read and regarded as one of the most significant young voices, to 1979, when he was the last of the major war poets still surviving. He appeared in the earliest popular anthologies of war poetry, including Marsh’s Georgian Poetry III and E. B. Osborn's The Muse in Arms, both published during the war. Osborn included three of Graves's poems, compared to Sassoon's two, Brooke's two, Gurney's four, and Robert Nichols's eleven. The anthology now reads oddly because it omits entirely the two writers generally considered today to be the major voices among active combatants, Owen and Rosenberg.