George Mallory

George Leigh Mallory, the son of the clergyman, Herbert Mallory, was born in Mobberley on 18th June 1886. His younger brother was Trafford Leigh Mallory (1892-1944).

At the age of thirteen, Mallory won a mathematics scholarship to Winchester College. A few years later one of the teachers at the school introduced him to mountaineering. This included a trip to the Alps.

In 1905 Mallory went to Magdalene College, Cambridge, to study history. While at university he became friends with Geoffrey Winthrop Young, Rupert Brooke, John Maynard Keynes, Duncan Grant and Lytton Strachey. After graduating Mallory became a teacher at Charterhouse where he taught Robert Graves, encouraging his interest in poetry and mountaineering. Graves later recalled: "He (Mallory) was wasted at Charterhouse. He tried to treat his class in a friendly way, which puzzled and offended them."

George Mallory met Ruth Turner at a dinner held by Arthur Clutton-Brock in 1913. The following year, her father, Hugh Thackeray Turner invited Mallory to join him and his three daughters on a family holiday in Venice. The couple fell in love after a trip to Asolo. Ruth wrote to George after she arrived back in England: "How wonderful it was that day among the flowers at Asolo!"

Ruth Turner became engaged to Mallory in April 1914. On 18th May George wrote to Ruth: "it's too too wonderful that you should love me and give me such happiness as I never dreamt of". Seven days later he was writing: "Oh! my arms are aching dear for you - to draw you swiftly and firmly close to me."

George told his brother, Trafford Leigh Mallory, that he intended to marry Ruth. He replied: "This is good news indeed. I am very pleased to hear it; heartiest congratulations! I must say I was extraordinarily surprised. However I suppose the influence of spring and Italy, combined with meeting the right person, fairly laid you by the heals."

Mallory married Ruth Turner on 29th July 1914. Geoffrey Winthrop Young was the best-man. Her father, Hugh Thackeray Turner, provided her with an annual income of £750 and arranged for them to live in a house close to the family estate in Godalming. The couple went to Porlock in Somerset for their honeymoon.

Mallory was deeply shocked by the outbreak of the First World War. He believed strongly that international disputes should be solved by diplomacy. Some of his friends, including Geoffrey Winthrop Young and Duncan Grant, were pacifists. Young became a war correspondent with The Daily News and his reports of the slaughter on the Western Front appalled Mallory.

His brother, Trafford Leigh Mallory, and two of his best friends, Robert Graves and Rupert Brooke, did join the British Army. Although opposed to the war, Mallory began to feel that he should do his duty and help the war effort. Geoffrey Winthrop Young resigned as a journalist and began to help to transport casualties and refugees away from the front-line. On 22nd November 1914 Mallory wrote to Young saying that it was "increasingly impossible to remain a comfortable schoolmaster". He added: "Naturally I want to avoid the army for Ruth's sake - but can't I do some job of your sort?"

On 9th December, 1914, the war minister, Lord Kitchener, instructed headteachers not to let teachers join up if this would impair the work of their schools. Frank Fletcher, the head of Charterhouse, used this directive to refuse permission for Mallory to join the armed forces. Mallory's guilt for not taking part in the war increased after hearing about the death of his friend, Rupert Brooke in April 1915.

The following month he received a letter from his brother, Trafford Leigh Mallory, who had just arrived at the front-line near Ypres. Despite the foul latrines and the smell of rotting bodies he told him that: "I must say I am extraordinarily happy here. I never thought I would enjoy it so much." However, within a few weeks of living in the trenches with having to deal with constant gas attacks his tone changed. "You have an alternative of putting your head down in the trench and being asphyxiated or putting it up over the trench into rapid fire. We have got gag things to put over our mouths, but still many seem to get killed."

On 16th June 1915 Leigh-Mallory was wounded in the leg during an attack on the German trenches at Ypres. As a result of the seriousness of his injury Leigh-Mallory was sent to a hospital in Oxford.

Ruth Mallory wrote to her husband on 10th August 1915: "I wonder dear how much we shall keep up with the times and be able to be proper companions for our children. Lets try and remember that they must educate us as well as we educating them then I think we may not go so far wrong, we mustn't hate every new thing that comes along until its got old." On 19th September 1915, Ruth gave birth to a girl who they named as Francis Clare. George had wanted a boy and he wrote to a friend: "I can't claim any great interest at present (in my daughter)."

Some of his favourite students joined the British Army. He wrote to a friend that losing them was "like cutting off buds". Mallory could no longer accept the idea that these young men should be fighting on his behalf and despite the protests of Frank Fletcher he decided to join the Royal Artillery. He wrote to a friend: "I feel so mixed up when I think of it - not wanting perfect safety for my own sake because I prefer adventure and want anyway to share those risks with my friends; but thinking so very differently where Ruth comes in. I'm afraid she'll feel very sore when I'm out there."

On 4th May 1916 Second Lieutenant George Mallory was sent to France. That night Ruth wrote to her husband: "I think I must write to you tonight it makes me feel less far from you. I am alright dear. I am cheerful and I have not cried anymore. I had baby as soon as I got home till she went to bed and it was very comforting. She is more of a comfort than anything else I could have." Mallory replied that her letters were like "great shafts of light which come pouring in on me".

Mallory was assigned to the 40th Siege Battery, then position in the northern sector on the Western Front. That summer he took part in the Somme offensive. He wrote to his wife about the bombardment that took place before the infantry attack: "It was very noisy. Field batteries again firing over our heads (of course there are plenty in front of us too) and most annoying of them a 60-pounder which has a nasty trick of blowing out the lamp with its vigorous blast."

Mallory wrote that he was "full of hope" that the offensive would be successful. On 14th July 1916 he sent another letter to Ruth Mallory arguing that: "It really seems as though we have given the Hun something of a whacking and also that his reserves are pretty well used up. Shall we find suddenly one day that the war is over - finished as dramatically as it began?" A few days later he was writing that "our hope of moving forward immediately seemed to have vanished."

Later that month George Mallory saw flamethrowers in action for the first time. He described how he saw "a sort of liquid fire, a long line of trenches apparently on fire and exploding with great flashes and clouds of sparks."

On 15th August 1916 he wrote about the large number of people killed during the Somme Offensive; "I don't object to corpses so long as they are fresh... With the wounded it is different. It always distresses me to see the." As a member of the Royal Artillery he was less likely to be killed or wounded than in the infantry. He told his wife: "The chance of survival in my branch of the services is very large."

Mallory was constantly worried about the dangers of killing his own men. He wrote in a letter to his wife about this fear: "Before I went to sleep I heard distinctly from the murmur of voices in the tent some mention of our troops being shelled out of a trench by our own guns... I can't tell you what a miserable time I had after that. You see, if my registration had been untrue, it was my fault... I went over and over again in my mind all the circumstantial evidence that it was really our shells I had seen bursting and had horrid doubts and fears."

Lieutenant Mallory went on leave in December 1916. When he returned to the Western Front he became a liaison officer to a French unit. He wrote a letter to his wife about the conditions on the front-line: "The surroundings are indescribably desolate and dotted with small crosses. We haven't many dead in the trenches (at least only one decapitated unfortunate has been discovered below the surface) but those outside could well do with some loose earth over them."

In May 1917 he was forced to return to England to have an operation on an ankle injury that made it very difficult to walk. In September 1917 Mallory was sent to Winchester to train on some new guns. He was later sent on a battery commander's course in Lydd.

Mallory returned to the Western Front in September 1918. He joined 515 Siege Battery RGA near Arras. His commanding officer was Gwilym Lloyd George, the son of David Lloyd George, the prime minister. He was with the company when the Armistice was declared on 11th November 1918.

Mallory served in France until January 1919. He returned to teaching history at Charterhouse and revived the college mountaineering group. Of the original sixty members, twenty-three had been killed and eleven more wounded.

According to the authors of The Wildest Dream: The Biography of George Mallory (2000): "David Pye suspected that George was also affected by guilt, as he had been reconsidering his own approach to teaching, and wondering whether he could have done more for the majority of his pupils rather than the favored few." Mallory, Pye and Geoffrey Winthrop Young, talked about opening their own progressive school.

George and Ruth Mallory both became active in the Labour Party. When the idea of a new progressive school did not get off the ground, Mallory applied unsuccessfully for a job with the Union of the League of Nations, a pressue group that favoured world government.

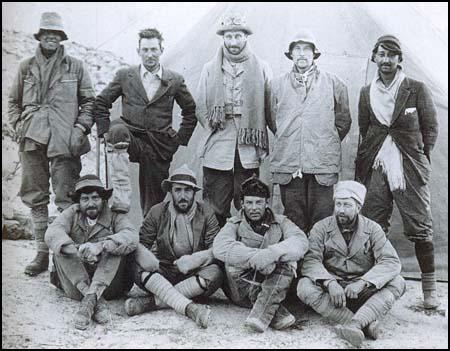

In 1921 Mallory was invited to join a reconnaissance expedition to Mount Everest. The following year he took part in an attempt to reach the summit, but the group was forced back by bad weather. However, Mallory and his colleagues reached a new world record altitude of just under 27,000 feet, a feat achieved without oxygen. Mallory was asked why he wished to climb Mount Everest and he replied: "Because it is there."

George Mallory, Edward Norton, Noel Odell and John Macdonald. Front row:

Edward Shebbeare, Geoffrey Bruce, Howard Somervell and Bentley Beetham.

George Mallory was considered to be the best mountain climber in the world. Harry Tyndale, who climbed with Mallory, argued: "In watching George at work one was conscious not so much of physical strength as of suppleness and balance; so rhythmical and harmonious was his progress in any steep place ... that his movements appeared almost serpentine in their smoothness." Geoffrey Winthrop Young added: "His movement in climbing was entirely his own. It contradicted all theory. He would set his foot high against any angle of smooth surface, fold his shoulder to his knee, and flow upward and upright again on an impetuous curve."

Mallory joined another expedition to Mount Everest in 1924. Approaching his 38th birthday, he considered that this would be his last chance to climb the world's highest mountain. Mallory and an excellent young climber, Andrew Irvine, set off from the highest camp for the top on 8th June. Both climbers were seen by Noel Odell through a telescope on the mountain's northeast ridge, only a few hundred metres from the summit. They never returned to high camp and died somewhere high on the mountain.

Robert Graves argued that "anyone who had climbed with George is convinced that he got to the summit." His close friend, Geoffrey Winthrop Young was also convinced that he conquered Everest. He wrote: "After nearly twenty years' knowledge of Mallory as a mountaineer, I can say that difficult as it would have been for any mountaineer to turn back, with the only difficulty past, to Mallory it would have been an impossibility." Tom Longstaff, who took part in the 1922 Everest expedition, added: "It is obvious to any climber that they got up.... Now, they will never grow old and I am very sure they would not change places with any of us."

Over the next thirty years there were several attempts to climb Mount Everest. In 1933, Percy Wyn-Harris discovered Irvine's ice-axe on a rock at around 27,500 feet (8380 m).

Everest was eventually conquered by Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay on 29 May 1953. They spent only about 15 minutes at the summit. They looked for evidence of the 1924 Mallory expedition, but found none.

In 1975, Wang Hongbao, a Chinese climber reported that he had seen the body of a at 8100m, while attempting to climb Everest. Wang was killed in an avalanche a day after the report and so the location was never precisely fixed. However, the only possible identity of the body was that of Mallory or Irvine.

The Mallory and Irvine Research Expedition, led by Eric Simonson, took place in 1999. The frozen body of Mallory was found at 26,760 feet (8,160 m) on the north face of the mountain. The body was remarkably well preserved due to the mountain's climate and from the rope-jerk injury around his waist, encircled by the remnants of a climbing rope, it appears that the two were roped together when Mallory fell. The body lay roughly below the location of Irvine's ice axe found in 1933. The fact that the body was relatively unbroken suggests that Mallory may not have fallen such a long distance as Irvine.

Clare Mallory believes that the evidence suggests that her father did reach the summit. He had promised his wife Ruth Mallory, to leave a photograph of her at the top of the mountain. As no photograph of Ruth was found on Mallory, she is sure that he must have left it on the summit.

Another clue was that Mallory's snow goggles were found in his pocket, suggesting that he and Irvine had made a push for the summit and were descending after sunset.

The First World War (£4.95)

Primary Sources

(1) George Mallory, letter to his wife, Ruth Mallory (14th July, 1914)

It really seems as though we have given the Hun something of a whacking and also that his reserves are pretty well used up. Shall we find suddenly one day that the war is over - finished as dramatically as it began? Not a very near day I fear - or rather I don't dare to hope.

(2) George Mallory, letter to his wife, Ruth Mallory (26th July, 1914)

Before I went to sleep I heard distinctly from the murmur of voices in the tent some mention of our troops being shelled out of a trench by our own guns... I can't tell you what a miserable time I had after that. You see, if my registration had been untrue, it was my fault... I went over and over again in my mind all the circumstantial evidence that it was really our shells I had seen bursting and had horrid doubts and fears.

(3) George Mallory, letter to his wife, Ruth Mallory (11th June, 1916)

It is extraordinary how the desire is growing within me to take part in a big offensive. I feel we must do it and when we do I want to be there - not for the excitement but because I want to fight in this cause.

(4) George Mallory, letter to his wife, Ruth Mallory (25th June, 1916)

It was very noisy. Field batteries again firing over our heads (of course there are plenty in front of us too) and most annoying of them a 60-pounder which has a nasty trick of blowing out the lamp with its vigorous blast. I took a good look round in the middle of the night from the top of our bank, it was a moving sight to see the flashes of many guns like numerous flickers of lightning.

(5) George Mallory, letter to his wife, Ruth Mallory (2nd July, 1916)

Our part was to keep up a barrage fire on certain lines, "lifting" after certain fixed times from one to another more remote and so on. Of course we couldn't know how matters were going for several hours. But then the wounded - walking cases - began to pass and bands of prisoners. We heard various accounts but it seemed to emerge pretty clearly that the attack was held up somewhere by machine-gun fire and this was confirmed by the nature of our own tasks after the "barrage" was over. To me, this result together with the sight of the wounded was poignantly grievous. I spent most of the morning in the map room by the roadside, standing by to help Lithgow (the Commanding Officer) to get onto fresh targets.

(6) George Mallory, letter to his wife, Ruth Mallory (14th July, 1916)

It really seems as though we have given the Hun something of a whacking and also that his reserves are pretty well used up. Shall we find suddenly one day that the war is over - finished as dramatically as it began? Not a very near day I fear - or rather I don't dare to hope.

(7) George Mallory, letter to his wife, Ruth Mallory (15th July, 1916)

The two mice which were building a nest of paper which they used to tear noisily each night were victimised in the first hour, and there were two more victims, mere visitors I suspect, last night. Rats, happily, don't infest my dugout but as they swarm in the neighbourhood I thought it wise to guard the entrance. A more useful purpose, however, seemed to be served by lending it to the officers' cookhouse - six rats were caught in an hour - we shall have to dig a special grave for the numerous corpses.

(8) George Mallory, letter to his wife, Ruth Mallory (15th August, 1916)

I don't object to corpses so long as they are fresh - I soon found that I could reason thus with them. Between you and me is all the difference between life and death. But this is an accepted fact that men are killed and I have no more to learn about that from you, and the difference is no greater than that because your jaw hangs and your flesh changes colour or blood oozes from your wounds. With the wounded it is

different. It always distresses me to see them.

(9) George Mallory, letter to his wife, Ruth Mallory (26th September, 1916)

It was thrilling and indescribable to see the hamlet they were attacking smothered with shellfire, running down a slope waiting until the barrage lifted and then pressing on again to reach the abandoned trench which had been their objective.

(10) Peter & Leni Gillman, The Wildest Dream: The Biography of George Mallory (2000)

On the face of things, George and Ruth seemed to have all they could have asked for. But there was still the question of Charterhouse. The euphoria of his first six months back home had helped George overcome his frustrations and his dislike of Fletcher, but his views of the inadequacies and flaws of the public school still held. He had made the point with some force while drafting his novel, The Book of Geoffrey, when he was in France. In one passage a father confronts a teacher and accuses him of destroying his son's innocence and inquisitiveness. Previously the boy had been "a pleasant companion full of young curiosity, a healthy animal, a proper English boy"; now he was selfish, prejudiced, and dull, a mental coward full of contempt for other people's views. "Superficial and self-satisfied, he is disastrously ill equipped for making the best of life."

Even more forthright, and strengthening the suggestion that George was evoking his own estrangement from his parents, is the father's accusation to the teacher: "When I gave him to you, he was lost to me. I knew him no longer and couldn't know him... His lips indeed spoke but his heart was closed from me and his mother." David Pye suspected that George was also affected by guilt, as he had been reconsidering his own approach to teaching, and wondering whether he could have done more for the majority of his pupils rather than the favored few. "Armed with his own experience, he would not attempt the same methods," Pye recorded.

As always, George tried to build on the lessons of frustration and disappointment. He, Pye, and Geoffrey Young began to consider opening a school of their own. Together with Ruth and Len Young, they met several times at the Holt to discuss the idea. George went so far as to prepare a draft prospectus for the school that made four key points. First, parents and teachers should work closely together. Second, rather than inhabit oases of privilege, pupils should learn about other worlds across the social divides.

They should he taught about craft and design, about farm work, and "the obligations of responsibility and disinterested effort." Third, there should be less of a distinction between lessons and leisure. Pupils should be under less pressure from the demands of the formal curriculum, and should be encouraged to develop initiative and self-reliance. Fourth, there should be fewer compulsory games. Pupils should be allowed to follow other pursuits and crafts, including walking and navigating through the countryside.

What was impressive about George's prospectus was the extent to Which it addressed faults in a divisive and examination-obsessed education system that has persisted in Britain since. The issues he raised are still relevant in the continuing debate between theories of child-centered and didactic education. Nor was the project unduly fanciful, since Prior's Field, which Ruth had attended, had been opened by Julia Huxley with just six pupils and similarly progressive principles in 1902, and was still thriving almost a hundred years later. What was more, Julia Huxley's husband had been a teacher at Charterhouse. George, Young, and Pye drew up more detailed plans hut in the end they lacked the collective will to see the scheme through. Pye eventually became provost of University College, London, while Young helped the German refugee Kurt Hahn when he founded Gordonstoun, the school in Scotland that emphasized the importance of honesty, integrity, self-reliance, and naked swimming.

(11) Richard Van Emden & Victor Piuk, Famous 1914-1918 (2008)

In writing to Ruth, each or every other day, George Mallory went out of his way to stress that he was relatively safe, certainly in comparison with front line soldiers. To a certain extent, this was not a false reassurance. He could see that serving in a Siege Battery in the Royal Garrison Artillery meant he was less likely to be killed and wounded than in the infantry, and he regularly indicated to his wife how fortunate he was: "The chance of survival in my branch of the services is very large." He did reveal once, but only long after the event, that a bullet had passed between himself and another man walking feet in front of him.

Yet his own position at the guns, although it by no means assured safety, did make him aware of the responsibility he owed to soldiers in the trenches whose survival was more tenuous, infantrymen whose lives he could save or take by the correct or incorrect registration of the guns under his direction.

Mallory served in a number of roles within the battery but his favourite was as Forward Observation Officer, and he frequently made his way to the trenches, learning to live with the gruesome sights that he saw.

(12) Peter & Leni Gillman, The Wildest Dream: The Biography of George Mallory (2000)

On June 8, the day George was last seen alive, Ruth and the children were on holiday at Bacton, a seaside resort in Norfolk. On June 19 they were back at Herschel House. That afternoon in London, Hinks received a coded telegram from Norton that read: "Mallory Irvine Nove Remainder Alcedo." "Nove" meant that George and Irvine had died, "Alcedo" that the others were unhurt. It thus fell to Hinks to convey the news to Ruth. He composed a telegram that was handed in at the post office at Kensington and dispatched from there to Cambridge, where it arrived at 7:30 p.m.

A short while later a delivery boy carrying the telegram called at Herschel House. Ruth cannot have been too surprised to see him, for in his letter of April 21 George had told her to expect a telegram announcing their success, although this was later than he had led her to expect...

Confusion must have compounded Ruth's sense of shock, for almost simultaneously, a reporter from The Times arrived at Herschel House. The Times, which was entitled to read all Norton's dispatches as part of its contract with the expedition, had been told about the deaths too. When challenged later to explain why it had sent a reporter to Herschel House, The Times claimed it was anxious to ensure that Ruth heard the news before reading in the next day's newspaper.

The most immediate decision Ruth faced was when, and how, to tell the children. By then they were in bed, and she decided to postpone the moment until the morning. She left them in the care of Vi, and went for a walk with some friends. In the morning, so Clare recalled seventy-five years later, Ruth took her, Berry, and John into the bed she had shared with George. "She lay between us told us this bad news," Clare said. "We all cried together."