E. P. Thompson

Edward Palmer Thompson, the second son of Edward John Thompson (1886–1946) and Theodosia Jessup Thompson (1892–1970) was born in Oxford on 3rd February 1924. His parents were Methodist missionaries and at the time of his birth, his father taught Bengali at Oxford University. His biographer, John G. Rule, "A Methodist by birth, upbringing, vocation, and education, he was in most respects an instinctive humanist and believer in the possibility of human betterment." (1)

Edward Thompson later recalled, that his upbringing was "supportive, liberal, anti-imperialist, quick with ideas and poetry and international visitors". (2) Edward and his older brother Frank Thompson, attended the progressive Dragon School. Frank went on to become a star pupil at Winchester College, whereas Edward was enrolled at his father's old school, the Methodist-founded Kingswood School. (3)

Frank Thompson was a growing influence on Edward's political ideas. Roderick Bailey has pointed out that his political consciousness rapidly matured, particularly when a boyhood friend was killed with the International Brigades during the Spanish Civil War. Frank and Edward both became strong supporters of the Popular Front Government. (4)

Freeman Dyson, one of Frank's schoolmates later commented: "His loud voice, his quick mind, his intense interest in all kinds of things and people, his crazy jokes, and his disrespect for authority epitomised some characteristics of young Frank, whose youthful and radical energy turned him swiftly into a strong anti-fascist militant." (5)

E. P. Thompson at Cambridge University

Thompson recalled that as a sixth former in 1940, reading the early work on the English Civil War of the Marxist historian Christopher Hill and the seventeenth-century Leveller writings by people such as John Lilburne, to which it led him, was a "breakthrough". (6) At eighteen he followed the example of his brother and joined the Communist Party of Great Britain. (7)

Edward Thompson studied history at Corpus Christi College, Cambridge. His studies were interrupted by the Second World War and as a member of the British Army saw action in Italy. His brother, Frank Thompson, who joined the Special Operations Executive (SOE), and in January 1944 was parachuted into occupied Macedonia. "Late in May he was caught, brutally interrogated, and, following a show trial in which he defended himself in Bulgarian and pronounced himself a communist, executed by firing squad alongside twelve captured partisans.... Together they died giving the clenched fist salute. He was not yet twenty-four." (8)

Edward Thompson believed that the war offered an opportunity to create a more equal society: "There was an active democratic temper throughout Europe... There was an active democratic temper throughout Europe. There was a submission of self to a collective good. Then as now there was a purposive alliance of resistance to power a 'popular front' which had not yet been disfigured by bad faith." (9)

Thompson returned to Cambridge University to finish off his degree: "A wartime degree could be gained by only two years' academic study, so he opted for a wartime BA and spent the scholarship which his first-class result earned him on individual study for the third year of his course. This year was spent working on Elizabethan and Jacobean literature and history and also in exploring a wide range of historical philosophers including Vico and Marx." (10)

At university he read A. L. Morton's pioneering work, People's History of England (1938). According to his biographer, "Morton's grass roots grand narrative based on common people rather than 'Great Men' indicated a new way of synthesis for a long tradition of popular histories. It opened up investigation for the Group into working-class formation and constructed the lineage of British radicalism down to the modern era." (11) When it was published in May 1938, it became the "monthly choice" of the Left Book Club and was dispatched to around 40,000 of its members, it was critically acclaimed and immediately popular. A crystallization of popular-front cultural politics, it also transcended its moment. Widely translated, it has seldom been out of print since. (12)

Communist Party Historians' Group

At a Communist Party of Great Britain meeting he met Dorothy Katharine Gane Towers who was completing her history degree after war service in industry. Edward and Dorothy began to live together in 1945 and married on 16 December 1948. As John G. Rule points out: "The Thompsons then had no inclination to pursue academic careers, and had already decided to move to the north of England, when Edward was offered a teaching post in the extra-mural department at Leeds University. Before taking up this post he and Dorothy had been involved with a volunteer international youth group in building a railway in Yugoslavia, another reinforcement of an internationalism that remained essential in his thinking, and which qualifies overdone attempts to portray him as a quintessentially English radical." (13)

Edward and Dorothy Thompson joined Eric Hobsbawm, Christopher Hill, Rodney Hilton, A. L. Morton, Raphael Samuel, George Rudé, John Saville, Dona Torr, Edmund Dell, Victor Kiernan and Maurice Dobb in forming the Communist Party Historians' Group. (14) Francis Beckett pointed out that these "were historians of a new type - socialists to whom history was not so much the doings of kings, queens and prime ministers, as those of the people." (15)

The group had been inspired by A. L. Morton's, People's History of England (1938). Christopher Hill, the group's chairman, argued that the book provided a "broad framework" for the group's subsequent work in posing "an infinity of questions to think about"; for Eric Hobsbawm, it would become a model in how to write searching but accessible history, whereas for Raphael Samuel, who first encountered the book as a schoolboy, it was an antidote to "reactionary" history from above. According to Ben Harker: "Morton was an inspiration for a rising generation of Marxist historians who would come to dominate their respective fields." (16)

In 1952 members of the Communist Party Historians' Group founded the journal, Past and Present. Over the next few years the journal pioneered the study of working-class history and is "now widely regarded as one of the most important historical journals published in Britain today." (17)

A member of the group, John Saville later wrote: "The Historian's Group had a considerable long-term influence upon most of its members. It was an interesting moment in time, this coming together of such a lively assembly of young intellectuals, and their influence upon the analysis of certain periods and subjects of British history was to be far-reaching." (18)

As Christos Efstathiou has explained: "Most of the members of the Group had common aspirations as well as common past experiences. The majority of them grew up in the inter-war period and were Oxbridge undergraduates who felt that the path to socialism was the solution to militarism and fascism. It was this common cause that united them as a team of young revolutionaries, who saw themselves as the heir of old radicalism." (19)

Thompson was also active in the peace movement and was active in the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND). Other members included J. B. Priestley, Bertrand Russell, Fenner Brockway, Frank Allaun, Donald Soper, Vera Brittain, Sydney Silverman, James Cameron, Jennie Lee, Victor Gollancz, Konni Zilliacus, Richard Acland, A. J. P. Taylor, Canon John Collins and Michael Foot.

Khrushchev's Speech on Stalin

During the 20th Party Congress in February, 1956, Nikita Khrushchev launched an attack on the rule of Joseph Stalin. He condemned the Great Purge and accused Joseph Stalin of abusing his power. He announced a change in policy and gave orders for the Soviet Union's political prisoners to be released. Harry Pollitt, General Secretary of the Communist Party of Great Britain, found it difficult to accept these criticisms of Stalin and said of a portrait of his hero that hung in his living room: "He's staying there as long as I'm alive". Francis Beckett pointed out: "Pollitt believed, as did many in the 1930s, that only the Soviet Union stood between the world and universal Fascist dictatorship. On balance, he reckoned Stalin was doing more good than harm; he liked and admired the Soviet leader; and persuaded himself that Stalin's crimes were largely mistakes made by subordinates. Seldom can a man have thrown away his personal integrity for such good motives." (20)

Thompson wrote to John Saville about the speech: "It is the biggest Confidence Trick in our Party's history. Not one bloody concession as yet to our feelings and integrity; no apology to the rank-and-file, no self-criticism, no apology to the British people, no indication of the points of Marxist theory which now demand revaluation, no admission that our Party had undervalued intellectual and ideological work, no promise of a loosening of inner party democracy, and of the formation of even a discussion journal so that this can be fought within our ranks, not one of the inner ring of the Executive felt that he might have to resign, if even temporarily." (21)

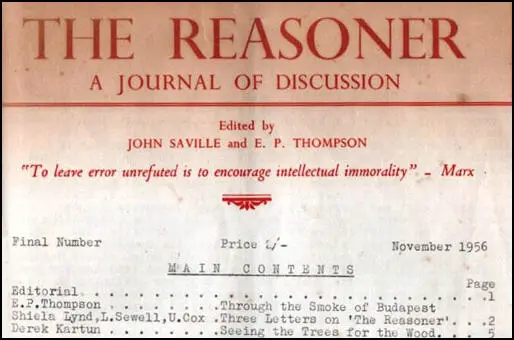

Thompson thought that Khrushchev's speech might allow more free discussion within the CPGB, and fellow historian, John Saville, began to produce the critical, but internally directed, journal The Reasoner. The masthead included the words of Karl Marx: "To leave error unrefuted is to encourage intellectual immorality". According to Thompson, "self-imposed restrictions" or even "actual suppression of sharp criticism" revealed the undemocratic nature of the CPGB. (22) Saville later admitted that "our main purpose in the first issue was to underline the backwardness, timidity and narrow bloody-mindedness of the leadership of the British party in their refusal to offer the opportunities for a serious analysis of the history of Soviet society." (23)

In its first edition Thompson and Saville highlighted the importance of freedom of expression in the Communist Party of Great Britain. "It is now, however, abundantly clear to us that the forms of discipline necessary and valuable in a revolutionary party of action cannot and never should have been extended so far into the processes of discussion, of creative writing, and of theoretical polemic. The power which will shatter the capitalist system and create Socialism is that of the free human reason and conscience expressed with the full force of the organised working-class. Only a party of free men and women, accepting a discipline arising from truly democratic discussion and decision, alert in mind and conscience, will develop the clarity, the initiative, and the élan, necessary to arouse the dormant energies of our people. Everything which tends to cramp the intellect and dull their feelings, weakens the party, disarms the working class, and makes the assault upon Capitalism - with its deep defences of fraud and force - more difficult." (24)

Typed onto stencils and the printed on a hand powered duplicator, Thompson and Saville published about 650 copies of The Reasoner (that number included a reprint of 300). They had a small advertisement in the daily worker but their request for a further notice of a reprint was refused. The Collet's Bookshops in London and Glasgow took copies. They received hundreds of letters of support including from Lawrence Daly, the militant trade unionist, Hymie Levy the mathematician, and Malcolm McEwen, the left-wing journalist. (25) Rodney Hilton believed the journal might become the best bridge between the different tendencies inside the labour movement. (26) The novelist, Doris Lessing, wrote to them saying: We have all been part of the terrible, magnificent, bloody, contradictory process, the establishing of the first Communist regime in the world - which has made possible our present freedom to say what we think, and to think again creatively." (27)

Two more editions of The Reasoner were published. James Friell (Gabriel) of the Daily Worker, provided cartoons for the journal. It took Thompson five days to type the 40,000 words. There were articles by the American economist, Paul Sweezy, George Douglas Cole, a member of the Labour Party, on democratic centralism, Robert W. Davies on Stalin's Purges and the Soviet Show Trials and Ronald Meek on the need for independent publications. (28) The CPGB was unwilling to allow even this form of dissidence and on 31st August 1956, its political committee that included Harry Pollitt, Rajani Palme Dutt and John Ross Campbell, ordered the publication to cease. When they refused Thompson and Saville were suspended from the CPGB. (29)

Khrushchev's de-Stalinzation policy encouraged people living in Eastern Europe to believe that he was willing to give them more independence from the Soviet Union. (30) In Hungary the prime minister Imre Nagy removed state control of the mass media and encouraged public discussion on political and economic reform. Nagy also released anti-communists from prison and talked about holding free elections and withdrawing Hungary from the Warsaw Pact. Khrushchev became increasingly concerned about these developments and on 4th November 1956 he sent the Red Army into Hungary. During the Hungarian Uprising an estimated 20,000 people were killed. Nagy was arrested and replaced by the Soviet loyalist, Janos Kadar. (31)

In the third issue The Reasoner Thompson and Saville condemned the overthrow of Nagy and called on the executive committee of the Communist Party of Great Britain to "dissociate itself publicly from the action of the Soviet Union in Hungary" and to "demand the immediate withdrawal of Soviet Troops". They then stated: "If these demands are not met, we urge all those who, like ourselves, will dissociate themselves completely from the leadership of the British Communist Party, not to lose faith in Socialism, and to find ways of keeping together. We promise our readers that we will consult with others about the early formation of a new socialist journal." (32)

The Thompsons, like most members of the Communist Party Historians' Group, supported Imre Nagy and as a result, like most Marxists, they left the Communist Party of Great Britain after the Hungarian Uprising and a "New Left movement seemed to emerge, united under the banners of socialist humanism... the New Leftists aimed to renew this spirit by trying to organise a new democratic-leftist coalition, which in their minds would both counter the 'bipolar system' of the cold war and preserve the best cultural legacies of the British people." (33)

Thompson acknowledged the role played by scholars like Ralph Miliband, Eric Hobsbawm, Christopher Hill, Rodney Hilton, A. L. Morton, Raphael Samuel, George Rudé, John Saville, Dona Torr, Edmund Dell, Victor Kiernan, V. Gordon Childe, Royden Harrison, Maurice Dobb and George Derwent Thompson in his political journey. He wrote in The Socialist Register: "To work as a Marxist historian in Britain means to work within a tradition founded by Marx, enriched by independent and complementary insights by William Morris, enlarged in recent times in specialist ways by such men and women as V. Gordon Childe, Maurice Dobbs, Dona Tarr and George Thompson, and to have as colleagues such scholars as Christopher Hill, Rodney Hilton, Eric Hobsbawm, V. G. Kiernan and (with others whom one might mention) the editors of this Register (John Saville and Ralph Miliband)." (34)

Thompson wrote to Eric Hobsbawm in 1975 that he missed Group meetings but acknowledged the long-term impact on his historical writing. Members of the Group were "formed within a certain unified cultural matrix, a certain 'moment', so that we must look a bit like a closed club, who share passwords and unspoken definitions and operate within a shared problematic which today can't be entered in the same way." (35) As Richard J. Evans pointed out: "These shared ideas and assumptions lent the former members of the Group of distinctive profile when they began to produce their major historical works in the late 1950s and 1960s." (36)

The New Reasoner

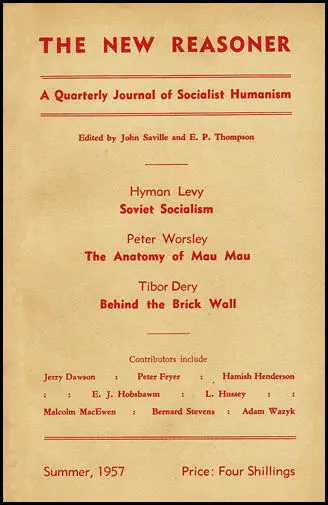

In July 1957, E. P. Thompson and former members of the Communist Party Historians' Group published the first edition of the socialist journal The New Reasoner. The editorial committee for the first issue included John Saville, Randall Swingler, Ronald Meek, Doris Lessing and Kenneth Alexander. (37)

According to Christos Efstathiou: "If The Reasoner tried to reform the CPGB from the inside, The New Reasoner was an effort to reform the Communist and labour movement outside the Party. The new journal looked for a radical third way beyond the Communist or Trotskyist schemes and the reformist tendencies of British labourism. It was no longer a journal of intra-party discussion, but a journal of 'socialist humanism', which tried to develop socialism with a humanist face, as its editors pointed out." (38)

The editors stated that the journal would carry theoretical and analytical articles and "a wide range of creative writing - short stories, polemic, satire, reportage, poetry, and occasional historical or critical articles - which contribute to the rediscovery of our traditions, the affirmation of socialist values, and the undogmatic perception of social reality." It included articles by E. P. Thompson (Socialist Humanism), Eric Hobsbawm (Dr Marx and the Victorian Critics), Peter Fryer (Hungarian Uprising), John Saville (Palme Dutt and Indian Independence), Jean-Paul Sarte (The French Socialist Party) and Peter Worsley (The Anatomy of Mau Mau). (39)

Dorothy Thompson became the business manager of the journal. Her biographer and friend, Sheila Rowbotham, pointed out: "Characteristically, her competence meant she was designated business manager, though she also read through submitted manuscripts. The break with the Communist party was painful, but it also brought hope in the creation of a new left. Dorothy worked with the writers, artists, historians and trade unionists who were forming the new left clubs in many towns." (40)

In April 1958, John Saville contacted Ralph Miliband, a lecturer at the London School of Economics, and a member of the Labour Party, inviting him to contribute to the journal with an essay "on some fundamental questions for socialists concerning the transition to socialism in Britain". (41) This was published as The Transition to the Transition and the same year The New Reasoner also published another article by Miliband on The Politics of Contemporary Capitalism. (42) At the end of the year he became the only person who had never been a member of the Communist Party of Great Britain to join the editorial board of the journal. (43)

William Morris: Romantic to Revolutionary

E. P. Thompson and Dorothy Thompson lived in Halifax for seventeen years. He taught in the extra-mural department at Leeds University. As John G. Rule has pointed out: "Thompson was perhaps fortunate to secure a post when doors were being closed against known communists. He did not see eye to eye on many things with the head of the department, S. G. Raybould, a noted writer on adult education with strong ideas of his own, but from all accounts Thompson was a successful teacher. Departmental records show him to have been committed and thoughtful, expecting a significant input from his students, many of whom were from working-class backgrounds." (44)

Thompson's adult education classes were mainly on literature but he also held classes on British history from the Industrial Revolution to the present. from an early age he had been interested in the utopian literature of William Morris and William Blake. Encouraged by Dona Torr, Thompson began work on a book about Morris. William Morris, Romantic to Revolutionary (1955) was divided into four parts; the first three narrated Morris biography, from his early moral results and artistic conflicts to his later socialist ideas. In the fourth part, named "Necessity and Desire", highlighted Morris tenet of an education of desire, an educational goal to "desire better, to desire more, and above all to desire in a different way." (45)

It has been argued that Thompson shared Morris view of education: "In contrast to the conformism of liberal education, Morris underlined the need for an imagination in education that would persuade learners to look for a better society. He criticised the parochial conceptualisations and moral values of the education of his time. As he reassessed Morris's work and thought, Thompson accepted Morris's critique of liberal values in education." (46)

Thompson described Morris as Britain's first important Marxist and the "greatest moral initiator of Communism within our tradition" and could stand as a useful advisor in present-day political strategies. "It is perhaps Morris's most important contribution to English culture to have brought his rich store of historical and artistic knowledge, and the passionate moral insight of a great artist, to the task of revealing the full meaning of this - the greatest step forward in man's cultural (as in his economic and social) life." (47)

The Making of the English Working Class

In 1959, the left-wing publisher, Victor Gollancz, approached Ronald W. Harris, the Master of Studies at The King's School, about editing a series of books suitable for undergraduates. Harris then contacted John Saville if he would be willing to write a book on working-class politics in the 19th century. Saville replied that he could not do this because of other commitments and recommended Thompson as an excellent replacement. "In my opinion Thompson would do a better job than anyone in this field. I would add a warning. He is a very busy person, and if you are interested in him, and he accepted, I should insist on a firm time table. I do not want to give the impression that he is unreliable. Emphatically he is not, but on the contrary extremely efficient; but he is an extraordinary vigorous and lively individual who carries on many things at the same time, and you will need a firm assurance that he will meet your deadline." (48)

Thompson accepted the commission as it would give him the opportunity to express his political philosophy, something he called "socialist humanism". Thompson regarded history as a powerful means of producing knowledge about the past and providing insight into the current political situation, and he wanted to use it as a weapon to challenge political apathy. For him, history was "above all, the discipline of context; each fact can be given meaning only within an ensemble of other meanings." (49)

In an article published several years later, Thompson argued: "History is a form within which we fight, and many have fought before us. Nor are we alone when we fight there. For the past is not just dead, inert, confining; it carries signs and evidence also of creative resources which can sustain the present and prefigure possibility." (50)

Thompson had been working on the subject since his early days at the Department of Adult Education in Leeds. e admitted in the preface of The Making of the English Working Class (1963) that: "This book was written in Yorkshire, and is coloured at times by West Riding sources... I have also learned a great deal from members of my tutorial classes, with whom I have discussed many of the themes treated here." (51)

He told a close friend in November 1953 that "I want to start work on a short history of the people of the West Riding (social and industrial) from about 1750 to the present day: this would take anything up to 10 years to complete, but it is something we need very much indeed in our tutorial class work, as a kind of companion volume to Cole and Postgate's 'Common People'. There is a real incentive to get on with this job, since there are plenty of people who are interested in the work and will make use of the results." (52)

The book published in 1963 presented the formation of the English working class from the period of the French Revolution to the 1832 Reform Act. Thompson divided it into three parts. The first part traced the traditional liberties, ideas of social justice, pre-industrial customs and dissenting religious or political ideas. The second part focused on the catastrophic changes industrialisation brought to the life of labourers: malnutrition, slums, high rates of mortality, child labour, street violence, drunkenness and disease. Most importantly, as the third part of the book demonstrates, working-class radicalism was never eliminated. "In English life: everything, from their schools to their shops, their chapels to their amusements, was turned into a battleground of class." (53)

David Eastwood has described the publication of The Making of the English Working Class as "truly alchemic". (54) Thompson's biographer, John G. Rule has stated: "By 1968 when it appeared in its first British paperback edition, it had already become an established classic. In a work which has come to be seen as the single most influential work of English history of the post-war period, Thompson set out to demonstrate how between 1790 and 1832, under the joint pressures of political oppression and economic exploitation, English working men came to see themselves as a class: a class both made by the changing circumstances in which they laboured and lived, and self-making in terms of the responses they made to this experience. By the time of the crisis over parliamentary reform in 1830–32, a form of working-class consciousness had emerged, drawing on past traditions of resistance and rights as well as on present experiences. Further, Thompson argued, against generations of traditional conservative writing, that consciousness included the possibility of political revolution, which came very close at more than one moment." (55)

Historians have claimed that book is the most significant exposition of socialist humanism in actual historical writing with its insistence that class was defined by men "as they live their own history". Others have pointed out that in the preface of the book, Thompson made the defining statement of the meaning of "history from below". He wrote: "I am seeking to rescue the poor stockinger, the Luddite cropper, the 'obsolete' hand-loom weaver, the 'utopian' artisan, and even the deluded follower of Joanna Southcott, from the enormous condescension of posterity." (56)

University of Warwick

Thompson's increasing reputation took him in 1965 to the directorship of the Centre for the Study of Social History at the newly opened University of Warwick and the family moved to Leamington Spa. His biographer described him as "At the beginning of his forties, he was an imposing figure. Tall and sparely built, his craggily handsome features were topped by an unusually thick head of hair, which flopped uncontrollably over his forehead. He had no particular affectation in dress, unless smoking small cigarettes alternately with hardly larger cheroots counts as such. The intensity of his gaze could be at first disconcerting, but it was his habit to listen properly to those who were speaking, for except in moments of anger he was not an interrupter." (57)

Thompson enjoyed a better relationship with the students that he did with the university administrators. In 1970 a series of protests took place at the university against its relations with corporations such as Barclay's Bank, Chrysler and Rootes Motors, culminating in the occupation of the Centre for the Study of Social History building. Some of them got access to administration files and discovered that the university was keeping records on the American radical historian and visiting professor David Montgomery, who jointly taught a course on labour history with Thompson. The files revealed that the university supported Rootes Motors's request to deport Montgomery because of his socialist activism. Thompson supported the students by distributing and publishing the files. (58)

Thompson explained his actions in an article he wrote for the New Society. "When student unrest erupts at a British university, two standard reactions can be expected. The first assumes that the students are alone responsible, and leads on to speculations as to their motives. The second assumes that responsibility may be charged to old-fashioned elements in the university administration and among senior academic staff, who have responded too slowly or too clumsily to legitimate student demands. There is, however, a third explanatory hypothesis, which most observers would overlook as being too improbable. This is the explanation that dominant elements in the administration of a university had become so intimately enmeshed with the upper reaches of consumer capitalist society that they are actively twisting the purposes and procedures of the university away from those normally accepted in British universities, and thus threatening its integrity as a self-governing academic institution; and that the students, feeling neglected and manipulated in this context, and feeling also - although at first less clearly - that intellectual values are at stake, should be impelled to action." (59)

Thompson was an early critic of the "betrayal" of socialism by the Labour governments of Harold Wilson. Along with Raymond Williams and Stuart Hall, he was an editor of the Mayday Manifesto in 1967, which explicitly sought to present a socialist alternative. (60) However, he remained in the Labour Party as he believed it was the home of Marxists: "As a Marxist (or a Marxist-fragment) in the Labour Party, I have always tried to envisage a politics that will enable us, in this country, to effect a transition to a socialist society - and a society a great deal more democratic, in work as well as in government, than our present one - without rupturing the humane and tolerant disposition for which our working class has often been distinguished, in this country, if not abroad." (61)

Although E. P. Thompson left the Communist Party of Great Britain he made it clear that he was still a Marxist and acknowledged the role played by scholars like Ralph Miliband, Eric Hobsbawm, Christopher Hill, Rodney Hilton, A. L. Morton, Raphael Samuel, George Rudé, John Saville, Dona Torr, Edmund Dell, Victor Kiernan, V. Gordon Childe, Royden Harrison, Maurice Dobb and George Derwent Thompson in his political journey. He wrote in The Socialist Register: "To work as a Marxist historian in Britain means to work within a tradition founded by Marx, enriched by independent and complementary insights by William Morris, enlarged in recent times in specialist ways by such men and women as V. Gordon Childe, Maurice Dobbs, Dona Tarr and George Thompson, and to have as colleagues such scholars as Christopher Hill, Rodney Hilton, Eric Hobsbawm, V. G. Kiernan and (with others whom one might mention) the editors of this Register (John Saville and Ralph Miliband)." (62)

Full-Time Writer

In 1971 Thompson left Warwick University to become a full-time writer. Thompson argued that academia had lost its vision and was now part of the business establishment. He criticised loyal academics who defended the system for their servility. He was also disillusioned by the general political apathy of the population, who supported the system through indifference. "For him, if the movement was not connected to a general opposition to the British establishment, it was doomed to fail." (63)

Edward's wife, Dorothy Thompson, now worked as a full-time university teacher at the University of Birmingham. The couple lived at Wick Episcopi, a splendid Georgian house on the outskirts of Worcester. Some of his writings were concerned with the defence of liberties against the state. These articles appeared in The New Statesmen, New Society, The Times Literary Supplement and in the quality newspapers. He also published the books, Whigs and Hunters (1975) and The Poverty of Theory (1978) (64)

E. P. Thompson was critical of the New History who he accused of turning the theories of Karl Marx into "scholostic idealism" and tended to treat it as a dogma rather than a "philosophical tradition". According to Thompson, the New Left had abandoned class politics and became an intellectual group without ties to the working class. He also attacked people like Perry Anderson and Tom Nairn for their dismissal of the historiography of the Communist Party Historians' Group in their underestimation of the experiences and revolutionary perspectives of the English proletariat. (65)

In the 1980s Thompson became an active peace campaigner. Thompson believed that in the Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher era the Cold War was entering a phase in which nuclear conflict was becoming probable. Much of his writing concentrated on this issue. Thompson's, Notes on Exterminism, the Last Stage of Civilization in the New Left Review (1980) provided a significant analysis of the stage the arms race had by then reached. It had become a self-sustaining system propelled by an internal dynamic and a reciprocal logic. (66) Thompson was a founder member of the European Nuclear Disarmament and Mary Kaldor predicted that in time he would be viewed, along with Mikhail Gorbachov and Václav Havel, as "one of the key individuals who influenced the course of events in the 1980s." (67)

Other books by Thompson included Writing by Candlelight (1980), Protest and Survive (1980), Customs in Common (1992), Witness Against the Beast (1994) on William Blake and Making History: Writings on History and Culture (1994).

Edward Thompson was in poor health for several years and died on 28th August, 1993.

Primary Sources

(1) E. P. Thompson and John Saville, The Reasoner (July 1956)

It is now, however, abundantly clear to us that the forms of discipline necessary and valuable in a revolutionary party of action cannot and never should have been extended so far into the processes of discussion, of creative writing, and of theoretical polemic. The power which will shatter the capitalist system and create Socialism is that of the free human reason and conscience expressed with the full force of the organised working-class. Only a party of free men and women, accepting a discipline arising from truly democratic discussion and decision, alert in mind and conscience, will develop the clarity, the initiative, and the élan, necessary to arouse the dormant energies of our people. Everything which tends to cramp the intellect and dull their feelings, weakens the party, disarms the working class, and makes the assault upon Capitalism - with its deep defences of fraud and force - more difficult... We take our stand as Marxists... History has provided the chance... for the scientific methods of Marxism to be integrated with the finest traditions of the human reason and spirit which we may best describe as Humanism.

(2) E. P. Thompson, The Making of the English Working Class (1963)

I am seeking to rescue the poor stockinger, the Luddite cropper, the 'obsolete' hand-loom weaver, the 'Utopian' artisan, and even the deluded follower of Joanna Southcott, from the enormous condescension of posterity. Their crafts and traditions may have been dying. Their hostility to the new industrialism may have been backward-looking. Their communitarian ideals may have been fantasies. Their insurrectionary conspiracies may have been foolhardy. But they lived through these times of acute social disturbance, and we did not. Their aspirations were valid in terms of their own experience; and, if they were casualties of history, they remain, condemned in their own lives, as casualties.

Our only criterion of judgement should not be whether or not a man's actions are justified in the light of subsequent evolution. After all, we are not at the end of social evolution ourselves. In some of the lost causes of the people of the Industrial Revolution we may discover insights into social evils which we have yet to cure. Moreover, the greater part of the world today is still undergoing problems of industrialization, and of the formation of democratic institutions, analogous in many ways to our own experience during the Industrial Revolution. Causes which were lost in England might, in Asia or Africa, yet be won.

(3) E. P. Thompson, New Society (19th February, 1970)

When student unrest erupts at a British university, two standard reactions can be expected. The first assumes that the students are alone responsible, and leads on to speculations as to their motives. The second assumes that responsibility may be charged to old-fashioned elements in the university administration and among senior academic staff, who have responded too slowly or too clumsily to legitimate student demands.

There is, however, a third explanatory hypothesis, which most observers would overlook as being too improbable. This is the explanation that dominant elements in the administration of a university had become so intimately enmeshed with the upper reaches of consumer capitalist society that they are actively twisting the purposes and procedures of the university away from those normally accepted in British universities, and thus threatening its integrity as a self-governing academic institution; and that the students, feeling neglected and manipulated in this context, and feeling also - although at first less clearly - that intellectual values are at stake, should be impelled to action.

(4) E. P. Thompson, The Great Fear of Marxism, The Observer (5th February, 1979)

Anyone who is even casually informed knows that Marxism, as an intellectual system, is in a state of crisis. The term 'Marxism' conceals an immense conflict going on between different claimants to the Marxist tradition. In Russia dissidents like Roy Medvedev are offering, in Marxist terms, scholarly exposures of the Stalin era - analyses which are refused publication by Soviet (Marxist-Leninist) publishing houses. In East Germany Rudolf Bahro, a Marxist, is imprisoned by a Marxist state for his stubborn and honest thought.

If we move from intellectual to political and social movements, the conflict is even more obvious. In Africa the most disparate regimes, from old-fashioned military tyrannies to more open societies with real democratic potential, all invoke the word 'Marxist'.

As a Marxist (or a Marxist-fragment) in the Labour Party, I have always tried to envisage a politics that will enable us, in this country, to effect a transition to a socialist society - and a society a great deal more democratic, in work as well as in government, than our present one - without rupturing the humane and tolerant disposition for which our working class has often been distinguished, in this country, if not abroad....

I am very much against sin, and especially against Russian sin. When the Russian state does not give me a pain in the head, it strikes my lower anatomy.

Now that my moral credentials are plain to the whole world, let us discuss serious matters.

These concern Cold War chain-reactions, the nuclear fission of diplomacy. The sequence has been this. From last October there was a long run-up to NATO's decision to 'modernize' its nuclear armoury. Mrs Thatcher and Mr Pym were the self-appointed cheerleaders of this operation, although they disdained to consult the British Parliament at any point. A 'new generation' of nuclear missiles, under US ownership and control, was to be planted all over West Europe, many on our own soil.

Soviet spokesmen repeatedly warned of the consequences of this decision; proposed discussions; and even made small gestures of concession. NATO spokesmen refused every advance and argued that discussion could only take place 'from strength': that is, from a posture of menace, after the decision.

The decision made nonsense of the trivial provisions of Salt 2. But it became clear, meanwhile, that the US Senate was not going to ratify even these trivial provisions, thereby indicating that top level nuclear détente would prove futile in the face of the American military and arms lobby. As this became clear, a trickle of Soviet dissidents went off to gaol.

On 12 December, at Brussels, NATO ratified its menacing plans in full. On 19 December, exactly one week later, the Soviet decision to enter Afghanistan was taken. The hawkism of the West directly generated the hawkism of the East - according to one account, Brezhnev was actually overruled by his own hawks. On the Cold War billiard-table, NATO played the Cruise missile ball, which struck the Afghan black, which rolled nicely into a Russian pocket. It was as if Mrs Thatcher, Mr Pym and Mr Bill Rodgers were there, perched on the leading Soviet tanks, waving to the astonished people of Kabul.

(5) Kate Soper, Radical Philosophy (March, 1997)

The articles, letters and memos poured from his desk in the sackful. At any moment, he might be found exhorting the masses in Trafalgar Square to `feel their strength' or manning the bookstall at the END bazaar; playing percussion in a fund-raising concert or haggling at the Czech embassy over the suppression of the Jazz Group; dialoguing with Charta 77 or marching at the head of an anti-NATO rally in Madrid; exposing the grotesqueries of the SDI programme or railing against the skullduggery of the Soviet Peace Committee. That the CIA and the KGB would both accuse each other of funding these activities only served to reaffirm the wisdom of pressing for a process of `citizens' detente' and for the adoption of a non-aligned position within the Western peace movement. This was to prove of critical importance, both in the impact it had on the politics and strategies of the latter, and in the space it opened up for trans-bloc dialogue between it and the independent peace initiatives and dissident groups in Eastern Europe. This was no easy dialogue to sustain, demanding as it did a keen sensitivity to differences of political priority and to the divergent conditions under which the various peace groups in both halves of Europe were at that time working. The story of its ideological complexities is yet to be told. But when it is, it will be clear that without Thompson's sense of historical eventuation and his punctilious concern for the individuals involved in the process, certain lines of East-West communication which contributed to the dramatic changes of the late eighties would not have been opened up.

To make these claims for Thompson's agency in the making of recent history is not to suppose he was the only influence on the internationalisation of the British peace movement, or that he singlehandedly either devised or promoted the END programme. Even less is it to suggest that he was responsible for the ending of the Cold War, which is the `absurdity' which some respondents have read into Mary Kaldor's obituary tribute in the Independent. What Kaldor actually claims is that, in the fullness of time, Thompson, along with Gorbachev and Havel, will be viewed as `one of the key individuals who influenced the course of events in the 1980s', and this point is hardly refuted either by an appeal to the steadfastness of Reagan and the hard right, or to Western `victory' in the Cold War, or even to the supposedly brute fact that the freeze ended because of the internal economic contradictions of the Soviet Union and the consequent transformation in its leadership. To argue that the Cold War collapsed because the Soviet Union collapsed is more in the order of an analytic statement than a piece of historical analysis. `Collapses' of that order do not take place in a vacuum, but in a context shaped by shifts of atmosphere and the emergence of altered logics; a context which in turn exerts a specific influence on the direction taken by the unfolding of the events it has helped to precipitate. If it is true that glasnost and perestroika came in response to domestic crisis, it is also true that its defence and foreign policy initiatives were informed by peace movement thinking, and that the climate of reception of these both within and without the Soviet bloc had been altered by exposure to the pressures of the nonaligned anti-nuclear campaign in the West. As the major architect and spokesperson of that campaign, Thompson can certainly be said to have played a key role in shaping the historical disposition of the late eighties. Even at the time, as Kaldor notes, he was wryly predicting the historical theft of the peace movement contribution. `This is the most serious political work I have ever done or will ever do in my life,' he wrote. `It won't last long. If we succeed a little, the politicians will move in and take it off us.'