Rodney Hilton

Rodney Hilton was born in Middleton, Manchester, on 17th November, 1916. He was the youngest child of John James Hilton, formerly a weaver, but by that time manager of the Middleton and Stone Co-operative Society, and his wife, Anne Howard Hilton.

Both his parents were Unitarians and active members of the Independent Labour Party. "Indeed the family was deeply rooted in the radical working-class history of Lancashire. Both grandfathers had been handloom weavers in their youth, and active in radical politics." (1)

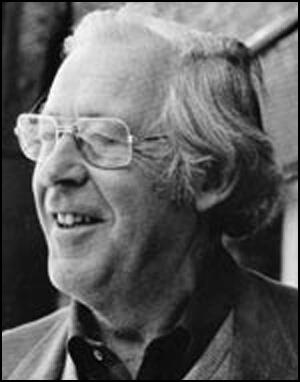

It has been argued that although he was deliberately irreligious he had all the "cultural attributes of Nonconformity." (2) Hilton went to Manchester Grammar School, and then to Balliol College, Oxford University. He encountered at Balliol such historians as Vivien Galbraith, Richard Southern, his life-long friend, Christopher Hill, and the future politician, Denis Healey. Along with Hill and Healey he became a Marxist and joined the Communist Party of Great Britain. (3) Hilton wrote later: "In those days a Marxist intellectual could not fail to be involved in politics and the almost inescapable choice in the late 1930s was the Communist Party." (4)

In 1938 he expected first-class degree in modern history. He had also, on 16th September 1939, married a fellow student and communist, Margaret Palmer, daughter of William Palmer, a civil servant in the Board of Trade. They had one son, Tim Hilton. (5) He then went on to a DPhil where he applied a Marxist analysis to the rural economy of Leicestershire between the 13th and l5th centuries, focusing on the emergence of agrarian capitalism. (6)

During the Second World War Hilton joined the British Army and served in North Africa, Syria, Palestine and Italy as a regimental officer in the 46th battalion of the Royal Tank regiment. According to Christopher Dyer, "He (Hilton) was reluctant later in life to say a great deal about his four years in the army during the second world war, but his experiences had a profound effect. In active service in North Africa, Syria, Palestine and Italy he saw terrible things, but there were lighter moments, such as inventing a cocktail by mixing gin and Owbridge's Lung Tonic in some remote middle eastern officers' mess. His politics gave him contacts with local people which were denied to most officers. As an historian, he was able to observe peasants at first hand, and he kept up an interest in the medieval near east after the war." (7)

In 1946 Hilton was appointed lecturer in history at the University of Birmingham, where he remained for the next 36 years. During this period he inspired an influential "Birmingham school" of medieval history, partly at seminars which combined scholarly plain speaking and high drinking. He was described by The Times as having "transformed the study of medieval social history with his Marxist analysis of social change". (8)

Communist Party Historians' Group

In 1946 several historians who were members of the Communist Party of Great Britain, that included Rodney Hilton, Christopher Hill, E. P. Thompson, Raphael Samuel, Eric Hobsbawm, A. L. Morton, John Saville, George Rudé, Dorothy Thompson, Dona Torr, Douglas Garman, Joan Browne, Edmund Dell, Victor Kiernan, Maurice Dobb, John Morris and Allan Merson, formed the Communist Party Historians' Group. (9) Francis Beckett pointed out that these "were historians of a new type - socialists to whom history was not so much the doings of kings, queens and prime ministers, as those of the people." (10)

The group had been inspired by A. L. Morton's People's History of England (1938). Christopher Hill, the group's chairman, argued that the book provided a "broad framework" for the group's subsequent work in posing "an infinity of questions to think about"; for Eric Hobsbawm, it would become a model in how to write searching but accessible history, whereas for Raphael Samuel, who first encountered the book as a schoolboy, it was an antidote to "reactionary" history from above. According to Ben Harker: "Morton was an inspiration for a rising generation of Marxist historians who would come to dominate their respective fields." (11)

At their first meeting on 26th October 1946, Christopher Hill suggested that the Group was divided into period subgroups, i.e. ancient, medieval, sixteenth-seventeenth centuries and the nineteenth century. The first committee was comprised of Hill as chairman and Eric Hobsbawm as treasurer. Other members of the committee included Douglas Garman, Joan Browne, John Morris and Allan Merson. Later the Communist Party Historians' Group formed a school teachers group. (12)

A member of the group, John Saville later wrote: "The Historian's Group had a considerable long-term influence upon most of its members. It was an interesting moment in time, this coming together of such a lively assembly of young intellectuals, and their influence upon the analysis of certain periods and subjects of British history was to be far-reaching." (13)

As Christos Efstathiou has explained: "Most of the members of the Group had common aspirations as well as common past experiences. The majority of them grew up in the inter-war period and were Oxbridge undergraduates who felt that the path to socialism was the solution to militarism and fascism. It was this common cause that united them as a team of young revolutionaries, who saw themselves as the heir of old radicalism." (14)

In 1950 Rodney Hilton with Hyman Fagan published the ground-breaking book, The Revolt of 1381. As Christopher Dyer pointed out: "He took medieval peasants seriously, as people with ideas, who were able to organise themselves in purposeful actions... Hilton saw in that rebellion, led by John Ball and Wat Tyler, a coherent programme and lasting effects, both of which were denied by historians who were less sympathetic towards the rebels." (15)

In 1952 members of the Communist Party Historians' Group founded the journal, Past and Present. Over the next few years the journal pioneered the study of working-class history and is "now widely regarded as one of the most important historical journals published in Britain today." (16)

Khrushchev's Speech on Stalin

During the 20th Party Congress in February, 1956, Nikita Khrushchev launched an attack on the rule of Joseph Stalin. He condemned the Great Purge and accused Joseph Stalin of abusing his power. He announced a change in policy and gave orders for the Soviet Union's political prisoners to be released. Harry Pollitt, General Secretary of the Communist Party of Great Britain, found it difficult to accept these criticisms of Stalin and said of a portrait of his hero that hung in his living room: "He's staying there as long as I'm alive". Francis Beckett pointed out: "Pollitt believed, as did many in the 1930s, that only the Soviet Union stood between the world and universal Fascist dictatorship. On balance, he reckoned Stalin was doing more good than harm; he liked and admired the Soviet leader; and persuaded himself that Stalin's crimes were largely mistakes made by subordinates. Seldom can a man have thrown away his personal integrity for such good motives." (17)

E. P. Thompson wrote to John Saville about the speech: "It is the biggest Confidence Trick in our Party's history. Not one bloody concession as yet to our feelings and integrity; no apology to the rank-and-file, no self-criticism, no apology to the British people, no indication of the points of Marxist theory which now demand revaluation, no admission that our Party had undervalued intellectual and ideological work, no promise of a loosening of inner party democracy, and of the formation of even a discussion journal so that this can be fought within our ranks, not one of the inner ring of the Executive felt that he might have to resign, if even temporarily." (18)

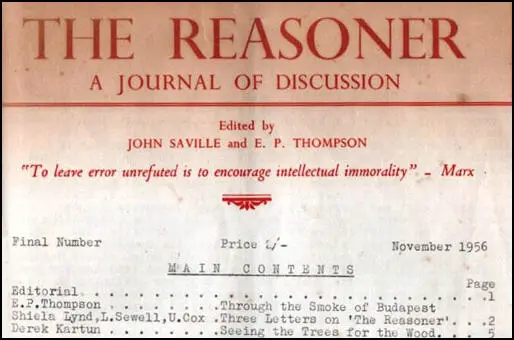

Thompson thought that Khrushchev's speech might allow more free discussion within the CPGB, and fellow historian, John Saville, began to produce the critical, but internally directed, journal The Reasoner. The masthead included the words of Karl Marx: "To leave error unrefuted is to encourage intellectual immorality". According to Thompson, "self-imposed restrictions" or even "actual suppression of sharp criticism" revealed the undemocratic nature of the CPGB. (19) Saville later admitted that "our main purpose in the first issue was to underline the backwardness, timidity and narrow bloody-mindedness of the leadership of the British party in their refusal to offer the opportunities for a serious analysis of the history of Soviet society." (20)

In its first edition Thompson and Saville highlighted the importance of freedom of expression in the Communist Party of Great Britain. "It is now, however, abundantly clear to us that the forms of discipline necessary and valuable in a revolutionary party of action cannot and never should have been extended so far into the processes of discussion, of creative writing, and of theoretical polemic. The power which will shatter the capitalist system and create Socialism is that of the free human reason and conscience expressed with the full force of the organised working-class. Only a party of free men and women, accepting a discipline arising from truly democratic discussion and decision, alert in mind and conscience, will develop the clarity, the initiative, and the élan, necessary to arouse the dormant energies of our people. Everything which tends to cramp the intellect and dull their feelings, weakens the party, disarms the working class, and makes the assault upon Capitalism - with its deep defences of fraud and force - more difficult." (21)

Typed onto stencils and the printed on a hand powered duplicator, Thompson and Saville published about 650 copies of The Reasoner (that number included a reprint of 300). They had a small advertisement in the daily worker but their request for a further notice of a reprint was refused. The Collet's Bookshops in London and Glasgow took copies. They received hundreds of letters of support including from Lawrence Daly, the militant trade unionist, Hymie Levy the mathematician, and Malcolm McEwen, the left-wing journalist. (22) Rodney Hilton believed the journal might become the best bridge between the different tendencies inside the labour movement. (23) The novelist, Doris Lessing, wrote to them saying: We have all been part of the terrible, magnificent, bloody, contradictory process, the establishing of the first Communist regime in the world - which has made possible our present freedom to say what we think, and to think again creatively." (24)

Two more editions of The Reasoner were published. James Friell (Gabriel) of the Daily Worker, provided cartoons for the journal. It took Thompson five days to type the 40,000 words. There were articles by the American economist, Paul Sweezy, George Douglas Cole, a member of the Labour Party, on democratic centralism, Robert W. Davies on Stalin's Purges and the Soviet Show Trials and Ronald Meek on the need for independent publications. (25) The CPGB was unwilling to allow even this form of dissidence and on 31st August 1956, its political committee that included Harry Pollitt, Rajani Palme Dutt and John Ross Campbell, ordered the publication to cease. When they refused Thompson and Saville were suspended from the CPGB. (26)

Khrushchev's de-Stalinzation policy encouraged people living in Eastern Europe to believe that he was willing to give them more independence from the Soviet Union. (27) In Hungary the prime minister Imre Nagy removed state control of the mass media and encouraged public discussion on political and economic reform. Nagy also released anti-communists from prison and talked about holding free elections and withdrawing Hungary from the Warsaw Pact. Khrushchev became increasingly concerned about these developments and on 4th November 1956 he sent the Red Army into Hungary. During the Hungarian Uprising an estimated 20,000 people were killed. Nagy was arrested and replaced by the Soviet loyalist, Janos Kadar. (28)

In the third issue The Reasoner Thompson and Saville condemned the overthrow of Nagy and called on the executive committee of the Communist Party of Great Britain to "dissociate itself publicly from the action of the Soviet Union in Hungary" and to "demand the immediate withdrawal of Soviet Troops". They then stated: "If these demands are not met, we urge all those who, like ourselves, will dissociate themselves completely from the leadership of the British Communist Party, not to lose faith in Socialism, and to find ways of keeping together. We promise our readers that we will consult with others about the early formation of a new socialist journal." (29)

Rodney Hilton, like most members of the Communist Party Historians' Group, supported Imre Nagy and as a result, like most Marxists, they left the Communist Party of Great Britain after the Hungarian Uprising and a "New Left movement seemed to emerge, united under the banners of socialist humanism... the New Leftists aimed to renew this spirit by trying to organise a new democratic-leftist coalition, which in their minds would both counter the 'bipolar system' of the cold war and preserve the best cultural legacies of the British people." (30)

Birmingham School of Medieval History

In 1963 Rodney Hilton became Professor of Medieval Social History. In the 1970s he was enthused by developments in the social sciences, returning always to the founders of social science, Karl Marx and Max Weber. (31) This was the background to the production of The English Peasantry in the Later Middle Ages (1975). Brian Manning points out that Hilton believed that the Marxist concept of the mode of production was crucial to understanding the moving forces of history. "He (Hilton) held that it was essential to recognise feudalism as a mode of production. This was the mode in which the ruling class of landowners/landlords exploited a class of peasants. The latter possessed their own means of subsistence but paid part of the fruits of their labour to their landlord in labour services, or rent in kind in money." (32)

Eric Hobsbawm has argued that Hilton's basic concern was with the broad historical problems to which Marxist historians were naturally drawn, and which were indicated by the title of his collection of papers, centrally concerned with the role of peasant resistance in creating the conditions for agrarian capitalism, Class Conflict and the Crisis of Feudalism (1985)... He was a co-founder in 1952 of its open-minded offshoot, the journal Past and Present, over whose editorial board he presided firmly from 1972 to 1987 and which played a role in British historiography analogous to the French Annales.... Common historiographical adversaries also brought him connections with the innovating wing of French historiography." (33)

Rodney Hilton, a supporter of the History Workshop Movement he wrote a great deal about women in the middle ages. He also explored the literature of the period, such as the ballads of Robin Hood, as an "insight into popular mentalities". He played an important role in developing the history of towns, which had been neglected in the general enthusiasm for peasants and agrarian studies in the previous decades and published "a series of innovative studies of medieval towns, placing them firmly in the framework of feudal society, not as the beginnings of modernity." (34)

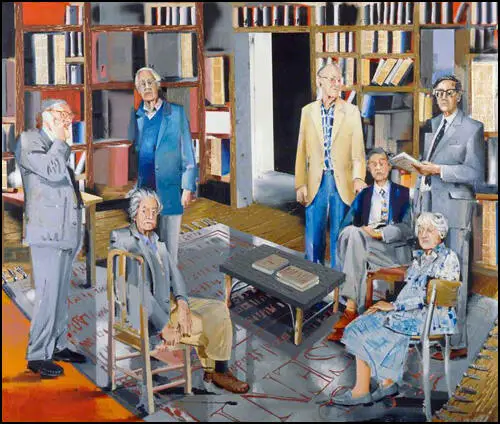

Standing: Eric Hobsbawm; Rodney Hilton; Lawrence Stone; Sir Keith Thomas;

seated: Christopher Hill; Sir John H. Elliott and Joan Thirsk (1999)

Rodney Hilton's books included: The English Peasantry in the Later Middle Ages (1975), The Transition From Feudalism to Capitalism (1976), Bond Man Made Free: Medieval Peasant Movements and the English Rising of 1381 (1977), Class Conflict and the Crisis of Capitalism (1985) and English and French Towns in Feudal Society: A Comparative Study (1995).

Eric Hobsbawm has pointed out that unlike his close friend, Christopher Hill, "Hilton was far from a natural puritan, and visibly comfortable with wine, women, song (preferably collective), and good food. He was probably best remembered by his students and friends in bars or in the presence of uncorked bottles". (35)

Rodney Hilton died of ischaemic heart disease on 7th June, 2002.

Primary Sources

(1) Brian Manning, Socialist Review (July, 2002)

He (Rodney Hilton) accepted that the Marxist concept of the mode of production was crucial to understanding the moving forces of history. He held that it was essential to recognise feudalism as a mode of production. This was the mode in which the ruling class of landowners/landlords exploited a class of peasants. The latter possessed their own means of subsistence but paid part of the fruits of their labour to their landlord in labour services, or rent in kind in money.

He made an important contribution in arguing that the peasants were a class, devoting the first chapter of his book The English Peasantry in the Later Middle Ages to this: (i) They possess, even if they do not own, the means of agricultural production by which they subsist. (ii) They work their holdings essentially as a family unit, primarily with family labour. (iii) They are normally associated in larger units than the family, that is villages or hamlets, with greater or lesser elements of common property and collective rights according to the character of the economy. (iv) Ancillary workers, such as agricultural labourers, artisans or building workers, are derived from their own ranks and are therefore part of the peasantry. (v) They support superimposed classes and institutions such as landlords, church, state, towns, by producing more than is necessary for their own subsistence and economic reproduction.'

(2) Christopher Dyer, The Guardian (10th June, 2002)

With the death of Rodney Hilton, at the age of 85, we have lost one of the most outstanding medieval historians of the 20th century, and a leading figure in Marxist history. His great achievement was to reveal new dimensions of the lives of medieval peasants and townspeople, and to outline the dynamic forces behind economic and social change.

He was born in Middleton, Lancashire, and brought up in a family with Unitarian and Independent Labour party traditions. He went to Manchester grammar school, and then to Balliol college, Oxford. He encountered at Balliol such medievalists as VH Galbraith and Richard Southern, and the Marxist historian of the 17th century, Christopher Hill.

Hilton practised leftwing politics in the Labour club and the Communist party, in the company of such activists as Denis Healey. In the turbulent late 1930s he still found time to work hard on his thesis, which he completed well within the three years now regarded as virtuous. He applied a Marxist analysis to the rural economy of Leicestershire between the 13th and 15th centuries, focusing on the emergence of agrarian capitalism. He left the Communist party in 1956, but then supported the New Left, and remained a steadfast advocate of the British Marxist tradition throughout his life.

He was reluctant later in life to say a great deal about his four years in the army during the second world war, but his experiences had a profound effect. In active service in North Africa, Syria, Palestine and Italy he saw terrible things, but there were lighter moments, such as inventing a cocktail by mixing gin and Owbridge's Lung Tonic in some remote middle eastern officers' mess. His politics gave him contacts with local people which were denied to most officers. As an historian, he was able to observe peasants at first hand, and he kept up an interest in the medieval near east after the war.

At the end of his military service in 1946, he was appointed to a lectureship at Birmingham university, after a no-doubt searching interview in the bar of the Mitre Hotel, Oxford, and he remained at Birmingham until his retirement in 1982. He was appointed to a personal chair in medieval social history there in 1963, and served for some years as head of the school of history in the late 1960s, a post which he gratefully relinquished to concentrate on research.

He took medieval peasants seriously, as people with ideas, who were able to organise themselves in purposeful actions. His writing about the peasant revolts at the beginning of his career included a book on The Revolt Of 1381 (with H Fagan, 1950). In 1973, Bondmen Made Free marked a return to these themes; it was a deservedly influential book which surveyed peasant unrest over many centuries and countries, and focused on the 1381 rising. Hilton saw in that rebellion, led by John Ball and Wat Tyler, a coherent programme and lasting effects, both of which were denied by historians who were less sympathetic towards the rebels. Hilton had been encouraged to revive his interest in revolts by the student rebellions of the 1960s, including the Birmingham "sit-in" of 1968.

In the 1970s he was enthused by developments in the social sciences, returning always to the founders of social science, Marx and Weber. This bore fruit in The English Peasantry In The Later Middle Ages (1975), the book of the Ford lectures which he delivered at Oxford in 1973. It contains the most satisfying discussion of the term "peasant" found in any recent historical writing.

Hilton's work kept up with new trends: he wrote about women in the 1970s, for example, and explored literature, such as the ballads of Robin Hood, as an insight into popular mentalities. He played an important role in developing the history of towns, which had been neglected in the general enthusiasm for peasants and agrarian studies in the previous decades. Just before he retired in 1982, and in the next few years, he published a series of innovative studies of medieval towns, placing them firmly in the framework of feudal society, not as the beginnings of modernity.

Hilton's work was deeply rooted in impeccably researched details from the archives, especially in the west midlands. His third book was an exploration of the west midlands region, circa 1300, in the manner of the regional studies then popular in France.

The development of archaeology as a source of historical information was helped by his organisation of an excavation of a deserted medieval village, with Philip Rahtz as the director. Hilton then boldly persuaded the university to appoint a lecturer in medieval archaeology in the school of history.

Telling examples and colourful episodes from the archives are found throughout his work, like the disorderly conduct of the turbulent and quarrelsome people of the small town of Halesowen in Worcestershire, whose behaviour demonstrated the social disruption caused by the growth of a new town.

He encouraged students to "do research", and the result was a steady stream of postgraduates who went on to produce work under his influence, and who are sometimes called "the Birmingham school". A typical example of the intellectual and social style that he encouraged was the "Friday night seminar", organised by postgraduates, in which a group met in a house or flat, each armed with a bottle of wine. Visitors wondered at the quality of discussion as the drink flowed.

Hilton's influence helped to change historical thinking in the second half of the 20th century. As a leading figure in the Communist party's historians' group his contribution might seem to have been confined to a small circle, yet one of the fruits of those discussions, a collective study of The Transition From Feudalism To Capitalism was eventually published in book form in 1976, when Marxist history was no longer regarded with such hostility. Out of the historians' group came the journal Past And Present, which sought to build bridges between Marxist historians and open-minded non-Marxists. After shaky beginnings in the 1950s, the journal grew into the leading historical forum for airing new ideas.

He spread his message about the importance of ideas in historical discourse throughout the world, partly through Past And Present, and partly through his wide range of international contacts. He gave lectures and attended conferences abroad, attracted research students from Israel and Argentina, was translated into many languages, and welcomed scholars from eastern and western Europe and the third world into his home. In the 1970s and 1980s he achieved the difficult feat of being admired by radical youth, while winning the acceptance of the establishment as a fellow of the British Academy (elected in 1977).

Those who spent time with Rodney Hilton appreciated his informal, irreverent and boisterous style. He gave his opinions robustly, and no one could get away in discussion with platitudes or a weakly supported generalisation. Any criticism, however, was usually delivered with good humour. He discussed theory and general ideas, but in unpretentious language, without jargon, and with such good sense that even hostile listeners found it hard to argue back. His conversations, though directed towards serious purposes, usually took place in bars or in the presence of uncorked bottles, and there was much profanity and outbursts of laughter.

He was married first to Margaret, with whom he had a son, Tim, a former art critic of the Guardian. By his second wife, Gwyn, he had two children, Owen and Ceinwen. His third wife, Jean Birrell, who also writes on medieval social and economic history, supported him through his most productive years and looked after him to the end.

(3) Graham Stevenson, Rodney Hilton (19th September, 2008)

Hilton was one of the leading medieval historians of the 20th century, and a leading figure in Marxist historiography. A lasting achievement of his was to open up understanding of the real lives of the medieval peasantry and ordinary townspeople.

He was born on November 17th 1916 in Middleton, Lancashire to a family with ILP traditions, went to Manchester Grammar School and then to Balliol College, Oxford. There, he encountered medievalists, VH Galbraith and Richard Southern, and the Marxist historian of the 17th century, Christopher Hill.

At university, Hilton joined the Labour Club and the Communist Party, in the company of Denis Healey. His thesis applied a Marxist analysis to the rural economy of Leicestershire between the 13th and l5th centuries, focusing on the emergence of agrarian capitalism.

During the Second World War, he was on active service in North Africa, Syria, Palestine and Italy. At the end of military service, in 1946, he was appointed to a lectureship at Birmingham University.

A leading figure in the Communist Party’s historians’ group, a collective study from these discussions, The Transition From Feudalism to Capitalism was eventually published by him in book form in 1976. Hilton left the Communist party in 1956 but remained a steadfast advocate of the British Marxist tradition throughout his life.

Hilton was appointed to a personal chair in medieval history at Birmingham University in 1963, and served for some years as the head of its school of history in the late 1960, a post he later left to concentrate on research. He remained at the university until his retirement in 1982.

He co-authored a book on the 1381 Peasants’ revolt, with the fellow Communist Hymie Fagan in 1950. Hilton was encouraged to resume a theoretical interest in revolts by the student rebellions of the 1960s, including the sit in at Birmingham University in 1968. In 1977, his Bondman Made Free marked a return to these themes. It was an influential book, which surveyed peasant unrest over many centuries and countries, though focusing on the 1381 rising. Hilton saw in those events a coherent programme and lasting effects, both of which were denied by more orthodox historians.

The English Peasantry In The Later Middle Ages (1975) was the book of the Ford lectures that he had delivered at Oxford in 1973. He wrote about medieval women in the 1970s and explored the ballads of Robin Hood as an insight into popular mentalities of his period. He played an important role in developing the history of towns, which had been neglected in the general enthusiasm for peasants and agrarian studies in the previous decades.

Just before he retired in 1982, and over the next few years, he published a series of innovative studies of medieval towns, placing them in the framework of feudal society, rather than the beginnings of modernity. Hilton’s work was rooted in impeccably researched detail from archival sources, especially of the West Midlands and another book was an exploration of that region in the 1300s.

Hilton became associated with the use of new archaeology as a source of historical information, best exemplified by his involvement in the excavation of a deserted medieval village. His work also revels in colourful episodes, such as the quarrelsome people of Halesowen, whose behaviour demonstrated the social disruption caused by the growth of a new town in his period of study. This heavy emphasis on detailed research and treating medieval folk as real people has influenced a trend in historians, sometimes called “the Birmingham school” in homage to his influence. He died at the age of 85, on June 7th 2002.

(4) Stephen R. Epstein, Rodney Hilton, Marxism and the Transition From Feudalism to Capitalism (September, 2006)

A founding member of the Historians’ Group of the Communist Party, of the journal Past and Present, and of a distinctive and distinguished School of History at the University of Birmingham, Rodney Hilton was among the most notable medieval historians of the latter half of the twentieth century. He was also the most influential of a small number of Marxist medievalists in Britain and Continental Europe who practised their craft before the renaissance of Marxist and left-wing history after 1968. Surprisingly, therefore, his work’s historiographical and theoretical significance has not attracted much attention.

Although Hilton was, first and foremost, a "historian’s historian", and made his most lasting contributions to the fields of English social, agrarian, and urban history, his engagement with Marxist historical debates cannot be lightly dismissed.

Hilton’s Marxism, a central feature of his self-understanding as a historian, reflects both strengths and weaknesses of British Marxist historiography in its heyday, and his interpretation of a locus classicus of Marxist debate, the transition from feudal to capitalist modes of production, still carries considerable weight among like-minded historians.

This brief essay proposes to identify the salient features of Hilton’s contribution to the ‘transition debate’; examine his move in the early 1970s to address certain problems he identified with that debate, and his renewed concern with the question of the ‘prime mover’; suggest reasons why this theoretical move was only partly successful; and, by way of

conclusion, set out briefly some lines of future empirical and theoretical engagement.Studies in the development of capitalism, first published in 1946, which proposed a model of the feudal mode of production that became the theoretical benchmark for all subsequent debates over the transition from feudalism to capitalism. Dobb followed Marx’s Capital in explaining England’s ‘truly revolutionary path’ to capitalism through class struggle - the ‘prime mover’ - and class differentiation in terms of property rights to land, and defined the historical and theoretical problems with which Hilton grappled throughout his life as a historian.

Marx’s theory of history rests on three pillars: a theory of class determination and class struggle; a theory of technological development; and a theory of the state, which - since the state requires a surplus to operate effectively - must include a political economy of markets.

However, for complex political and historiographical reasons that cannot be explored here, Dobb based his model on class struggle alone. This gave rise to two serious weaknesses in his and his followers’ approach to the transition from feudalism to capitalism.

First, Dobb’s model aimed in essence to explain the transition to capitalism, that is, to explain why the feudal mode of production was destined to fail in a ‘general crisis’ vaguely dated between the fourteenth A crucial influence on Hilton and most other British Communist historians formed during the 1940s and 1950s came from Maurice Dobb’s

and the seventeenth century.Dobb argued that this failure was caused by systemic disincentives to capital accumulation and innovation, including peasant over-exploitation; but he did not have a convincing explanation for why the feudal mode of production had been capable of expanding, territorially, economically and technologically, for more than half a millennium before the crisis. The absence of a positive theory of development - which is a central feature of the Marxist theory of history

and which must, ultimately, be mediated by some kind of scarcity-based transactions - probably also expressed the ‘anti-market bias’ that coloured Dobb’s views of socialist planned economies when he wrote the Studies in the 1930s and 1940s. At that time, as he later recalled, he underestimated ‘the role of prices and economic incentives’ in socialist economies, and his view of the feudal economy was clearly analogous.That bias, and the subordination of positive incentives and markets in Dobb’s scheme were reinforced by his subsequent debate with the American Marxist economist Paul Sweezy, a debate that canonised the misleading theoretical alternative among Marxists between long-distance trade as an exogenous, independent cause of change, or ‘prime mover’, and petty commodity production as an endogenous source of historical evolution.

Student Activities

References

(1) Eric Hobsbawm, Rodney Hilton: Oxford Dictionary of Nationary Biography (8th January 2009)

(2) Christos Efstathiou, E. P. Thompson: A Twentieth-Century Romantic (2015) page 15

(3) Christopher Dyer, The Guardian (10th June, 2002)

(4) Christos Efstathiou, E. P. Thompson: A Twentieth-Century Romantic (2015) page 4

(5) Eric Hobsbawm, Rodney Hilton: Oxford Dictionary of Nationary Biography (8th January 2009)

(6) Graham Stevenson, Rodney Hilton (19th September, 2008)

(7) Christopher Dyer, The Guardian (10th June, 2002)

(8) The Times (21st June 2002)

(9) Emma Griffin, History Today (2 February 2015)

(10) Francis Beckett, Enemy Within: The Rise and Fall of the British Communist Party (1995) page 134

(11) Ben Harker, Arthur Leslie Morton: Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (11th October 2018)

(12) Christos Efstathiou, E. P. Thompson: A Twentieth-Century Romantic (2015) pages 30-31

(13) John Saville, Memoirs from the Left (2003) page 88

(14) Christos Efstathiou, E. P. Thompson: A Twentieth-Century Romantic (2015) page 28

(15) Christopher Dyer, The Guardian (10th June, 2002)

(16) Emma Griffin, History Today (2nd February 2015)

(17) Francis Beckett, Enemy Within: The Rise and Fall of the British Communist Party (1995) page 144

(18) E. P. Thompson, letter to John Saville (4th April, 1956)

(19) E. P. Thompson and John Saville, The Reasoner (1st July, 1956)

(20) John Saville, Memoirs from the Left (2003) page 106

(21) E. P. Thompson and John Saville, The Reasoner (1st July, 1956)

(22) John Saville, Memoirs from the Left (2003) page 108

(23) Christos Efstathiou, E. P. Thompson: A Twentieth-Century Romantic (2015) page 59

(24) Doris Lessing, letter to the The Reasoner (29th July, 1956)

(25) John Saville, Memoirs from the Left (2003) pages 108-111

(26) Christos Efstathiou, E. P. Thompson: A Twentieth-Century Romantic (2015) page 66

(27) William J. Tompson, Khrushchev: A Political Life (1995) pages 153-154

(28) Simon Hall, 1956: The World in Revolt (2015) pages 346-347

(29) E. P. Thompson and John Saville, The Reasoner (4th November, 1956)

(30) Christos Efstathiou, E. P. Thompson: A Twentieth-Century Romantic (2015) page 55

(31) Christopher Dyer, The Guardian (10th June, 2002)

(32) Brian Manning, Socialist Review (July, 2002)

(33) Eric Hobsbawm, Rodney Hilton: Oxford Dictionary of Nationary Biography (8th January 2009)

(34) Christopher Dyer, The Guardian (10th June, 2002)

(35) Eric Hobsbawm, Rodney Hilton: Oxford Dictionary of Nationary Biography (8th January 2009)