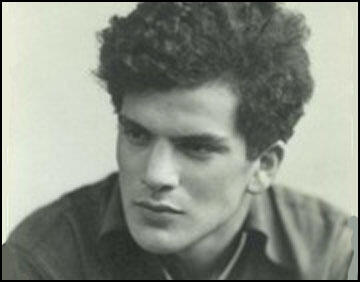

John Cornford

Rupert John Cornford, the son of Francis Macdonald Cornford (1874–1943) and Frances Crofts Cornford (1886–1960), was born in Cambridge on 27th December 1915.

His father was professor of ancient philosophy at Cambridge University and his mother, the grand-daughter of Charles Darwin, was a published poet. He was named Rupert in memory of Rupert Brooke, who had been killed in the First World War just before he was born.

At the age of nine Cornford was sent as a boarder to Copthorne Preparatory School in Sussex. Francis Macdonald Cornford later recalled: "At Copthorne he became absorbed in cricket. His headmaster said that his style, as a player, was the most incredible he had ever seen. But his knowledge of the history of the game was exhaustive... Later, his knowledge of the more democratic Association Football became no less extensive."

In 1929 he obtained a scholarship to Stowe School. The following year he was joined by his brother, Christopher: "Already, by the time I joined him at Stowe in the autumn of 1930, he had begun to be critical of the school, as indeed of everything else. He was already anti-militarist and atheist - one of his favourite pastimes was to tie up the school chaplain in metaphysical knots during the Tuesday afternoon religious talks."

The following year he began writing poetry that had been inspired by the work of W.H. Auden, T.S. Eliot and Robert Graves. He also developed an interest in politics. Christopher Cornford recalled: "As young as fourteen and a half he became sympathetic to Socialism. As we strode together through the school grounds, among the great beech trees and lakes, the rotundas and monumental obelisks, in shiny blue serge Sunday suits and stiff collars unloosed, he explained to me the principles of the nationalisation of industry and the injustices of our economic system."

Cornford also began reading books written by G. D. H. Cole, Harold Laski, Rajani Palme Dutt, Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. He claimed that Cole's plan for socialism "isn't powerful enough emotional position to accumulate the colossal reserves of energy and fanaticism that are needed to bring through a revolution without violence". Cornford preferred Marx to Cole: "Cole's Socialism is without the strength of Communism because it is without the really important part of Marxism, his dialectical materialism and the interpretation of history." He described Palme Dutt as "extraordinarily intelligent, but almost equally bitter."

In 1932 he read Das Kapital and the Communist Manifesto. He also wrote a letter to his brother about the criticism that Karl Marx had received from Harold Laski. " It seems to me dishonest for men like Laski to dismiss the Marxist interpretation of history and yet proclaim Marx as a great prophet, because his wonderfully accurate prophecy is dependent on his interpretation of history. Where it seems to me that he went wrong is in applying terms like the class-struggle (which is a legitimate abbreviation of what actually happens) as the whole and simple truth. It's far more complicated than he seemed to realise. But I believe that in this, too, his limitations are important in making him intelligible."

When he was only sixteen he won an exhibition to Trinity College. Cornford spent that summer in London. He joined the Young Communist League and spent a lot of time at the London School of Economics. He also had a poem published in the Listener before taking up his place at university in October 1933. According to Michael De-la-Noy: "During his three years at Cambridge he wrote only nine poems, for he was spending fourteen hours a day on political activities."

A fellow student at university was Victor Kiernan. He later recalled: "He had his philosophy, or rather instinctive attitude, of which friends got only glimpses; not that lie was secretive, but that he followed Lenin in his contempt for all useless sentiment and psychological weakness. He recalled one's ideas of what Lenin was like in other ways. His politics, unlike those of many middle-class Socialists, were not based on humanitarianism alone. To him the movement was something that could call out and realise all his powers; it was the only atmosphere he could breathe."

Cornford became very concerned about Adolf Hitler gaining power in Nazi Germany. In an article that he wrote in The Cambridge Left journal in 1934 he argued: "Fascism strives to cripple the working-class movement by murdering and torturing its leaders, suppressing its legal organisations and press, removing the right to strike in defence of wages and conditions, and all political rights whatsoever. Fascism exploits the Nationalist feelings of the petty bourgeoisie to divert their hostility towards the existing regime by whipping up a chauvinist frenzy against some foreign scapegoat - in Germany the Jews; in Poland the Ukrainian minority."

In March 1935 Cornford became a full member of the Communist Party of Great Britain. Despite the amount of time he spent on his political activities he achieved first classes in both parts of the history tripos (1935 and 1936). Cornford also became romantically attached to Rachel Peters and she gave birth to his illegitimate child. He later left Peters for Margot Heinemann.

Kenneth Sinclair Loutit recalled how John Cornford and James Klugman tried to recruit him into the Socialist Society: "My second meeting with James Klugman must have been after my return from Germany. He was accompanied by John Cornford. As contemporaries we all knew each other by sight, and Klugman remembered his previous recruiting visit. They said, very reasonably, that it was only by working together that people sharing the same goals could hope to achieve them, so I really could not do other than join the University Socialist Society. I had already told James the year before that I was not a joiner... John Cornford then took over asking what I saw as the most important thing for the next decade."

John Cornford wrote an article explaining why so many university students were joining the Communist Party of Great Britain. "The last few years have seen a considerable growth of Communist influence in the universities... It is no longer a phenomenon that can be dismissed as an outburst of transient youthful enthusiasm. It has established itself so firmly that any serious analysis of trends in the universities must take it into account... Communism in the universities is a serious force. It is serious because students do not easily or naturally become Communists. Communism has to fight down more prejudices, more traditions, more simple distortions of fact, than any other political organisation. It would not have gained ground without a serious appeal."

In 1936 Trinity College gave him a scholarship, and he planned to study the Elizabethans. However, on the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War he decided to go to Spain. Cornford reached Barcelona on 8th August 1936. He wrote to Margot Heinemann about the revolutionary spirit he found in Spain: "In Barcelona one can understand physically what the dictatorship of the proletariat means.... The mass of the people ... simply are enjoying their freedom. The streets are crowded all day, and there are big crowds round the radio palaces. But there is nothing at all like tension or hysteria... It is genuinely a dictatorship of the majority, supported by the over-whelming majority.

He met Franz Borkenau, an Austrian journalist, and the two men decided to travel to the front-line. He had already made up his mind to join the Worker's Party (POUM) army. He told his father in a letter: "After I had been three days in Barcelona it was clear, first, how serious the position was; second, that a journalist without a word of Spanish was just useless. I decided to join the militia."

Tom Wintringham later explained why Cornford had joined a group that was strongly influenced by the political ideas of Leon Trotsky and hostile to Joseph Stalin and his government in the Soviet Union: "In Barcelona he (John Cornford) found that the militia was being organized by the trade unions and political parties. He had no papers from England: he had not even brought his party membership card with him. So when he applied to the Hotel Colon, then the military headquarters of the party in which Barcelona's Socialists and Communists had joined forces, he was told to wait. Friendly but precise Germans, people taught by Bismarck as well as by exile to carry all necessary documents with them at all times, told him that he could not join the Thaelmann group, or any other unit of foreign volunteers organized by the United Socialist Party, until his standing as a known anti-Fascist was guaranteed by some document or by some person they knew. John was too restless, impatient for this. He flung off to join a rival party's militia, that of the P.O.U.M."

Cornford took part in an action at Perdiguera. He wrote to Harry Pollitt about his whereabouts and to inform him of the realities of the military situation in Spain. He also told Margot Heinemann about the battle he had taken part in and how it was reported in the POUM newspaper: "Today I found with interest but not surprise the distortions in the POUM press. The fiasco of the attack at Perdiguera is presented as a punitive expedition which was a success."

Cornford fought at Aragon in August 1936. The following month he fell ill and was sent to hospital. The authors of Journey to the Frontier have argued: "The precise nature of John's illness has never been established... it was disabling, and he suffered a few truly difficult days." Cornford was sent back to Cambridge to recuperate.

Cornford decided to use this as an opportunity to persuade some of his old friends to go to Spain. Bernard Knox later recalled: "In September I received a letter from my friend John Cornford, the leader of the Communist movement in Cambridge, who had just returned from Spain, where he had fought for a few weeks on the Aragon front, in a column organized by the Partido Obrero de Unificación Marxista, the POUM, a party that was later to be suppressed as too revolutionary. He had returned to England to recruit a small British unit that would set an example of training and discipline (and shaving) to the anarchistic militias operating out of Barcelona. He asked me to join and I did so without a second thought."

Cornford recruited a group of twelve friends to join the International Brigades. Knox went with him to see his father, Francis Macdonald Cornford. "He had served as an officer in the Great War and still had the pistol he had had to buy when he equipped himself for France. He gave it to John, and I had to smuggle it through French Customs at Dieppe, for John's passport showed entry and exit stamps from Port-Bou and his bags were likely to be given a thorough going-over."

Cornford took the men to Albacete, where they received some military training. Bernard Knox later recalled: "Our British section was assigned (mainly, I suppose, because I could serve as interpreter) to the French Battalion, where we ended up in the compagnie mitrailleuse, the machine-gun company. But for the rest of September and all through October we had no machine guns, not even rifles; the only weapon around was John's pistol, which he kept well under wraps. Since we couldn't train with weapons, our days were spent practicing close-order drill (French, English, or sometimes Spanish) and going on route marches along the dusty roads of the province of Murcia. No one knew when or where we would be sent to fight when (if ever) the weapons arrived, though the scuttlebutt rumors had us held in reserve for a flanking movement via Ciudad Real that would take Franco, now moving steadily toward Madrid, in the rear."

Bernard Knox fought alongside Cornford in Spain. "Our baptism of fire was sharp and unexpected. We were scattered with our machine-guns along a crest which we had every reason to believe was as safe as anything could be in the Madrid area (which wasn't very safe), when we heard our first shell. Nobody minded much, because it burst a good forty yards behind us, but the next two or three showed us that they were feeling for the crest we were occupying... Our commander had gone up to advanced positions that night with one of our gun-crews, so John took over command that morning, inspecting the positions we had taken up, and criticising ruefully the way in which most of us came down the cliff. But it was not a bad performance for raw troops taken by surprise in a barrage."

Cornford took part in the battle for Madrid and on 7th November 1936, and received a severe head wound. Sam Russell was with him when it happened: "When the smoke cleared there was John Cornford with blood pouring down his face and head. We later discovered that it was one of our own anti-aircraft shells that had fallen short and had come through the side of a wall. They took John off and that afternoon he came back with his head bandaged, looking very heroic and romantic."

While recovering he wrote some of his most important poems including Heart of the Heartless World. On 8th December, 1936, Cornford wrote to Margot Heinemann: " No wars are nice, and even a revolutionary war is ugly enough. But I'm becoming a good soldier, longish endurance and a capacity for living in the present and enjoying all that can be enjoyed. There's a tough time ahead but I've plenty of strength left for it. Well, one day the war will end - I'd give it till June or July, and then if I'm alive I'm coming back to you. I think about you often, but there's nothing I can do but say again, be happy, darling, And I'll see you again one day."

John Cornford insisted on going back to the front-line where he joined the recently formed British Battalion. He was killed near Lopera on 27th December 1936, his twenty-first birthday. According to Francis Beckett, the author of Enemy Within - the Rise and Fall of the British Communist Party (1995), Cornford was killed trying to retrieve the body of Ralph Fox. Cornford's best known work was published after his death: The Last Mile to Huesca and Poems from Spain.

Primary Sources

(1) Francis Macdonald Cornford, John Cornford: A Memoir (1938)

Before his schooldays he seemed to lack physical courage. After he had learnt to swim, at a picnic up the river he and the other children said they wanted to bathe. The others went in out of their depth, but John refused to follow. As he had said he would bathe I was afraid he would be ashamed afterwards, and argued with him for nearly half an hour, urging him just to go into the water and holding a punt-pole for him to catch hold of. But he kept saying he had `lost his nerve,' and I had to give it up.

He had a series of enthusiasms, each of which absorbed him while it lasted. His passion for butterflies (inherited from me - I did most of the catching) ended abruptly when he heard at a lecture on natural history that, thanks to collectors, some species were becoming extinct. He came back and said: "I shall never catch another butterfly as long as I live," and he never did. At Copthorne he became absorbed in cricket. His headmaster said that his style, as a player, was the most incredible he had ever seen. But his knowledge of the history of the game was exhaustive. All his money was spent on cricket books, and he would ask one to guess how many of the side which played for Sussex in (say) 1900 had a certain letter in their initials. Later, his knowledge of the more democratic Association Football became no less extensive. He was better at football, where his weight and strength told, and at Stowe he learnt to box. He and his Stowe friends, however, made it a point of principle to escape compulsory games as much as possible.

(2) Christopher Cornford, John Cornford: A Memoir (1938)

His letters from Copthorne are nearly all detailed accounts of football and cricket matches written in sporting journalese: from Stowe his letters begin to tell of books read and essays written. But John remained, as he always had been, passionately interested in sport. Years later, a common enthusiasm for the cup-tie or the test match formed a point of contact with the workers. He was never good at games himself, as he lacked the fundamental grace and sense of using the body that is the essential of the athlete. Though he was strong and well-built, he stooped badly and so restricted his lung-capacity. His hands were rounded and almost feminine; his eyes seemed not to be looking at what they were seeing, but looking beyond it, speculating, analysing. The height of his achievement was the second house-team at Rugby football and a cautious twenty for the opening pair in an even less eminent cricket team. But he had a minor genius for inventing games: we spent hours on Sunday afternoons racing boats (small twigs or bits of straw) down a little stream in the school grounds; and many more hours swiping at a rubber ball with a piece of packing-case in the squash courts-when these were not being used for their customary purpose. This game was the ancestor of another, played with a coal-shovel and a tennis-ball in John's rooms at Trinity. There was also a hide-and-seek game which appealed to John for the scope it gave for the skilled use of terrain.

In spite of his physical clumsiness, however, John was extremely effective; he could always beat me at any game, by sheer force of will, though I was the better athlete. I can scarcely remember an occasion, whether at ping-pong, golf, squash-rackets, or a race run backwards between two lamp-posts, from which John did not emerge the victor....

But the most remarkable, the main thing about John, was his terrific rate of development, his burning energy. If I am to say anything about him, I must say this, at the risk of repeating a conclusion which the rest of this book will make obvious. "Forging ahead" is a well-worn expression, but it is the best I can think of to describe his life. Trying to know him was like standing on a railway embankment and trying to grab an express train.

Already, by the time I joined him at Stowe in the autumn of 1930, he had begun to be critical of the school, as indeed of everything else. He was already anti-militarist and atheist-one of his favourite pastimes was to tie up the school chaplain in metaphysical knots during the Tuesday afternoon religious talks. Poor wretched chaplain! I have never seen anyone look so harassed and hunted as he looked after three-quarters of an hour with John. Subsequently, when some of the compulsory evening chapel services were made voluntary (resulting in a notable drop in attendance), John, I believe, was more to be thanked than anyone. .

As young as fourteen and a half he became sympathetic to Socialism. As we strode together through the school grounds, among the great beech trees and lakes, the rotundas and monumental obelisks, in shiny blue serge Sunday suits and stiff collars unloosed, he explained to me the principles of the "nationalisation of industry" and the injustices of our economic system. "But don't go shouting about it," he said, "or you'll make yourself unpopular."

(3) John Cornford, letter to Sidney Schiff (November 1931)

The election seems to me a piece of sheer political lunacy on the part of the electorate. The government has no sort of programme or policy whatever - and it takes into office nothing whatever except a record of political dishonesty almost as great as the socialists, or greater. I think there'll be trouble in the North before long, if the Communists organise the unemployed as well as the suffragettes were organised in 1913.

(4) John Cornford, letter to Christopher Cornford (1932)

I have bought myself Das Kapital and a good deal of commentary on it, which I hope to find time to tackle this term. Also The Communist Manifesto, with which I was a little disappointed, though part of it was an extremely remarkable prophecy. Also a pamphlet, Wage Labour and Capital (only 50 pp., do buy it and read it with FMC if ever you have time, as it is perfectly intelligible) which is (I think) a summary of the economic argument of Das Kapital. Most of Laski's criticism would seem to be directed against Engels' introduction. I found nothing whatever to quarrel with in the main thesis of Marx's own section. It seems to me dishonest for men like Laski to dismiss the Marxist interpretation of history and yet proclaim Marx as a great prophet, because his wonderfully accurate prophecy is dependent on his interpretation of history. Where it seems to me that he went wrong is in applying terms like the class-struggle (which is a legitimate abbreviation of what actually happens) as the whole and simple truth. It's far more complicated than he seemed to realise. But I believe that in this, too, his limitations are important in making him intelligible.

(5) Victor Kiernan, John Cornford: A Memoir (1938)

He had an odd way of laughing, a chuckle that seemed extorted from him against his will, as though he felt the world was too serious a place to laugh in. Nobody would have dreamed of calling him Jack, in spite of his, in many ways, simplicity and youthfulness. Before the end he was tired of student work, and wanted to be out in the world. A political job, he used to tell me, was the only sort he could "tolerate"; he admitted that he had not yet enough experience to be able to organise, for example, a strike. He had his philosophy, or rather instinctive attitude, of which friends got only glimpses; not that lie was secretive, but that he followed Lenin in his contempt for all useless sentiment and psychological weakness. He recalled one's ideas of what Lenin was like in other ways. His politics, unlike those of many middle-class Socialists, were not based on humanitarianism alone. To him the movement was something that could call out and realise all his powers; it was the only atmosphere he could breathe. Once when he was in a philosophical frame of mind I asked him what single thing in the universe gave him most satisfaction, and lie answered, after thinking for a minute, "the existence of the Communist International." One accepted such an answer from him as unvarnished truth. Another time, when I asked him whether he would not have preferred to live a century after the Revolution, in an era of peaceful construction, he said, decidedly, "No"; and he did in fact enjoy finding himself in an epoch of storm and stress, oppression and revolt, tyranny and heroism. There was nothing of sacrificing self to duty. Of all his qualities this was perhaps the most fundamental; and the most profoundly impressive to Socialist intellectuals, most of whom are prone to ask themselves whether they like their political work and usually consider that they do not. Cornford was not at all a conscious ascetic. He liked eating and drinking; he had, however, no conventional needs, and in dingy lodgings in Cambridge or in Guildford Street he felt quite at home and looked quite in place. A colleague of Lenin's tells how, when he first came to London, Lenin showed him round the town, and pointed out Westminster Abbey as one of " their" chief buildings - "'they" being the bourgeoisie. Cornford had the same sense of absolute separation from the "enemy," of irreconcilable antagonism and difference. The barricade was his most real symbol. For him, "they" were not merely oppressive, they were empty; they forced every one else to live wretchedly in order to maintain a manner of life which did not even make themselves happy. For him, also, the Revolution was as unquestionable a certainty as the Resurrection to a Christian. He visualised the bourgeoisie as fully aware of the fact, and shaking in their shoes (he used a coarser metaphor).

(6) John Cornford, The Cambridge Left (Spring 1934)

Fascism strives to cripple the working-class movement by murdering and torturing its leaders, suppressing its legal organisations and press, removing the right to strike in defence of wages and conditions, and all political rights whatsoever. Fascism exploits the Nationalist feelings of the petty bourgeoisie to divert their hostility towards the existing regime by whipping up a chauvinist frenzy against some foreign scapegoat - in Germany the Jews; in Poland the Ukrainian minority.

But it is of fundamental importance to be under no illusions as to the class basis of Fascism. It is the dictatorship of big capital, although its terrorist troops may be drawn from the petty bourgeoisie. It is only necessary to show the class-composition of Hitler's "General Economic Council," of whom nine are industrialists, four are bankers, and two are big agrarians. It is not accidental that Hitler has not carried out a single detail of the "Socialist" side of his programme, which included nationalisation of the trusts, the banks, and the big department stores.

This is of great importance, because it shows that there is nothing revolutionary about Fascism. Although the forms of rule may be different, the class-content is the same. Fascism develops quite logically out of capitalist democracy - it is in no sense a revolutionary break with it. What we are witnessing is a process of fascination through the democratic machinery. Bruning, von Papen, and Schleicher "constitutionally" prepared the way for Hindenburg to invite Hitler (also "constitutionally," through the single loophole in the "water-tight" Weimar constitution) to power. At no period was there a revolutionary overthrow of the democracy. And those gentlemen who talk about democracy versus dictatorship are therefore completely distorting the actual historical process.

(7) John Cornford, Communism in the Universities (1936)

The last few years have seen a considerable growth of Communist influence in the universities. That influence has often been over-estimated, particularly by the Right Wing Press after the Oxford motion. But none the less it persists and it is growing. It is no longer a phenomenon that can be dismissed as an outburst of transient youthful enthusiasm. It has established itself so firmly that any serious analysis of trends in the universities must take it into account.

This influence has shown itself in a steadily growing volume of left-wing activities. In 1933 the storm aroused by the famous Oxford "King and Country" motion swept every university, and in the majority of Unions this motion was passed by a large margin. That same winter the students of Cambridge got themselves into the newspapers by a 11th November demonstration which successfully kept a, three-mile march unbroken, fighting almost the whole way against students who were trying to break it up. In 1934 the Hunger Marchers received a great welcome from the students of Oxford and Cambridge. In 1935 the Northern Universities put themselves on the map when Sheffield students played a real part in the unemployment light in February. For a few days Sheffield Communist students sold over 200 copies of the Daily Worker in a university of 800 students. At the end of 1935 it was significant how rapidly student opinion reacted to the Hoare-Laval plan. At very short notice big protest meetings were held at King's College, London, the, London School of Economics, and Manchester. It would perhaps be true to say that the students reacted more quickly than any other organised body. Then at the beginning of this year the Federation of Student Societies, the revolutionary students' organisation, and the University Labour Federation formed a united body covering 2000 students in all the universities. During all this period the membership of' the Communist Party, though even now not very large, has grown steadily and continuously without once looking back.

Of course it would be wrong to represent this movement as wholly and solely the work of the Communist Party. But it is none the less true that everywhere the Communists have played a continuously active and leading part, and that the disciplined and centralised leadership of the Communist Party has given the movement a direction and co-ordination of which no other body would be capable.

Thus Communism in the universities is a serious force. It is serious because students do not easily or naturally become Communists. Communism has to fight down more prejudices, more traditions, more simple distortions of fact, than any other political organisation. It would not have gained ground without a serious appeal.

(8) Kenneth Sinclair Loutit, Very Little Luggage (2009)

My second meeting with James Klugman must have been after my return from Germany. He was accompanied by John Cornford. As contemporaries we all knew each other by sight, and Klugman remembered his previous recruiting visit. They said, very reasonably, that it was only by working together that people sharing the same goals could hope to achieve them, so I really could not do other than join the University Socialist Society. I had already told James the year before that I was not a joiner. His manner had a hint of recognition that at last virtue was starting to prevail, that I was beginning to see the light. This was too reminiscent of Father Gilbey, and it triggered my renewed refusal.

John Cornford then took over asking what I saw as the most important thing for the next decade. To me avoiding the "New German" road was the first priority along with beating unemployment. I was ready to share activities bearing on these ends, but I was not ready to spend time in debate or in 'study group' activities. Though I was not a pacifist, I also believed that war and militarism were neither a cure for unemployment nor a substitute for using the League of Nations. I therefore agreed to be in the group that, on Armistice Day, would lay a wreath of white peace poppies on the Cambridge War Memorial. On November the eleventh 1934 I joined the peace procession to the War Memorial. There was a fracas near Peterhouse where a large group of undergraduates did not approve of the banner "Workers by Hand and Brain Unite against War". There is a good photo of this in Stanski and Abrahams "Journey to the Frontier" (1966, Constable) showing the faces of a future UK High Court judge and two Colonial Governors. Unfortunately, one face is lacking. It is that of a young man who did not share my views but for whom I retain an affectionate respect. His reactions, just as he was facing up to strike out at me, were a part of a now-vanished code. He had pushed me round and was gathering up his punch when he suddenly dropped his guard and said, "No, I can't, it's Loutit; after all we have rowed in the same boat." We exchanged a brief uneasy smile and, sadly, our paths have never crossed again. This is an example of that 'Old Boy' system so disliked by Peter Wright, but should Beale, the stroke of that boat we shared with seven others, ever read these words he will know that his forbearance has never been forgotten. It had in it something noble and eminently civilised. I was mildly disappointed in the lack of interest in me shown by my old beach playmate, Donald Maclean. I recognised that he was living on a plane to which I did not aspire and that, reciprocally, he did not consider me to be worth much notice. We did have the chance of meeting later, when he certainly made up for this earlier neglect. In fact it was from him, in Moscow sometime in the 1960s, that I learnt of the Stanski and Adams book. He gave me his copy - after cutting out the fly-leaf that must have borne a private inscription. I did not know John Cornford well, as this was impossible without following him into his Party life. I believe that his version of that life was pretty idiosyncratic. Had he not died in Spain, he would certainly have got into trouble with the Party orthodox. As things were, I saw enough of him to respect and to like him. John had a middle initial to his name - 'R'. It stood for Rupert - his mother was of the Rupert Brooke generation and had been one of the "neo-pagans" who had animated Cambridge life in the decade before the 1914 war. They had in fact done much more than live their own lives in their own way. They provided a franchise for us who were to come after; they showed that young people could be both independent and responsible.

The quicksilver rapidity of John's emotional and intellectual appreciation did not come from his Marxist companions, from Klugman's faith. It came from his mother's generation, from that generation of uncles peopling the 1914 war cemeteries, those who did not live to tell us their tales personally. Not for nothing had John been nurtured with Darwins, Raverats and Keyneses. It was no accident that he, like many of his contemporaries, had been at that Malting House School created by Susan Isaacs and Geoffrey Pyke, whose pioneering genius (from which I was later allowed to benefit myself) has been so insufficiently appreciated. Afterwards John went to Dartington; his life and way reflected more that of his Rupert namesake's than that of any CP stereotype. He was more true to the Rupert heritage than the left has ever conceded. The approval of the political left shown by the older Cambridge intelligentsia, was due to their seeing it as a continuation of the intense liberal generosity of their own youth. They saw exactly this in young people like John Cornford; but from their Cambridge Elysium, that older generation was sensitively fearful of the emergence of both the aparatchik and Stalinism. It all seemed to them as but shadows fleeting over the back of their safe cave.

(9) John Cornford, letter to Margot Heinemann (10th August, 1936)

Last night we began to make ourselves more comfortable-dug little trenches to sleep in and filled them with straw. So long as I am doing anything, however purposeless, I feel fine. It's inactivity that just cats at my nerves. But the night before last I had a dream. One of the toughest people when I was small at school was the captain of rugger, an oaf called D. I was in the same dormitory and terrified of him. I hadn't thought of him for years, but last night I dreamt extremely vividly about having a fight with him and holding my own, and I think that's a good omen. I don't know how long we stay on this hill, but I am beginning to settle down to it. ...

Now a bit about the political situation. That isn't easy to get straight, particularly as I haven't yet heard anyone explain the position of the Party (and the militia here I am with are P.O.U.M. - left sectarian semi-Trotskyists). But roughly this. The popular front tactics were worked magnificently to begin with. They won the elections. And under the slogan of defence of the Republic, they enabled us to arm the workers when the Fascist revolt started. Up till then the position is quite clear. But now in Catalonia things are like this. There is a left Republican Government. But, in fact, the real power is with the workers...

In Barcelona one can understand physically what the dictatorship of the proletariat means. All the Fascist press has been taken over. The real rule is in the hands of the militia committees. There is a real terror against the Fascists. But that doesn't alter the fact that the place is free-and conscious all the time of its freedom. Everywhere in the streets are armed workers and militiamen, and sitting in the cafes which used to belong to the bourgeoisie. The huge Hotel Colon overlooking the main square is occupied by the United Socialist Party of Catalonia. Further down, in a huge block opposite the Bank of Spain, is the Anarchist headquarters. The palace of a marquis in the Rambla is a C.P. Headquarters. But one does not feel the tension. The mass of the people ... simply are enjoying their freedom. The streets are crowded all day, and there are big crowds round the radio palaces. But there is nothing at all like tension or hysteria. It's as if in London the armed workers were dominating the streets - it's obvious that they wouldn't tolerate Mosley or people selling Action in the streets. And that wouldn't mean that the town wasn't free in the real sense. It is genuinely a dictatorship of the majority, supported by the over-whelming majority.

(10) John Cornford, The Situation in Catalonia (1936)

The Anarchists still have the support of the majority of the Barcelona workers. They have two organisations: the C.N.T., a mass trade union: the F.A.I., which is in fact a disciplined political party, but because the Anarchists refuse to recognise political action, it is called a cultural organisation. Their programme has been: libertarian communism, organisation of industry by the Trade Unions, power to be won by outbreaks of unplanned revolutionary violence. Thus their leadership of the working class has been a record of continual and disastrous defeats. But they have preserved their influence because in the past, in a country which under Primo was 83 per cent. illiterate, they have understood better than any other worker's party in Catalonia how to present their objectives clearly and simply: and they have fed the desire of the workers to struggle with continuous - though disastrous - action. Thus they have won to their ranks some of the finest, most courageous, most idealist of the Catalan workers.

Now great changes are taking place. In spite of their opposition to politics, this year the Anarchist workers voted solidly together in the elections. Step by step the old Anarchist Terrorist Utopianism is being driven back: by the growing strength and leadership of the united Communists and Socialists: by the magnificent responsibility and organising power of the workers in their own Trade Unions, who are more and more adopting, though not yet consciously, the line of the Communists and Socialists, and will not permit wrecking tactics by their leaders. It is a painful and difficult process: but step by step they are being forced to abandon their ideals before the realities of the struggle. Thus they still refuse to take part in the official government: and their pressure forced the Communist members of the Government to withdraw: but in fact on the C.C. of the militia they are assuming the responsibilities of Government. In words they will not recognise the need for discipline in their militia columns: but the realities of the war have forted the necessity of some kind of discipline on them: but they insist on calling it `organised indiscipline.' The factories owned by C.N.T. Committees co-operate with Government representatives.

(11) Tom Wintringham, English Captain (1939)

In Barcelona he found that the militia was being organized by the trade unions and political parties. He had no papers from England: he had not even brought his party membership card with him. So when he applied to the Hotel Colon, then the military headquarters of the party in which Barcelona's Socialists and Communists had joined forces, he was told to wait. Friendly but precise Germans, people taught by Bismarck as well as by exile to carry all necessary documents with them at all times, told him that he could not join the Thaelmann group, or any other unit of foreign volunteers organized by the United Socialist Party, until his standing as a known anti-Fascist was guaranteed by some document or by some person they knew. John was too restless, impatient for this. He flung off to join a rival party's militia, that of the P.O.U.M.

(12) Bernard Knox, Premature Anti-Fascist (1998)

In September I received a letter from my friend John Cornford, the leader of the Communist movement in Cambridge, who had just returned from Spain, where he had fought for a few weeks on the Aragon front, in a column organized by the Partido Obrero de Unificación Marxista, the POUM, a party that was later to be suppressed as too revolutionary. He had returned to England to recruit a small British unit that would set an example of training and discipline (and shaving) to the anarchistic militias operating out of Barcelona. He asked me to join and I did so without a second thought.

I knew no more about Spanish politics and history than most of my fellow-countrymen, that is to say, not much. I had read (in translation) much (but not all) of Don Quixote, and seen reproductions of the great paintings of Velázquez and Goya. I knew that Philip II had married an English reigning Queen - Mary - and on her death claimed the throne of England, but had been defeated when in 1588 he sent the great Armada to invade England and enforce his claim. I knew that the Duke of Wellington had fought a long, hard campaign against Napoleonic armies in Portugal and Spain and that guerrilla (which was to become my military specialty in World War II) was a Spanish word. But I had no real understanding of the complicated situation that had produced the military revolt of July 1936. What I did know was that Franco had the full support of Hitler and Mussolini. In fact, that support had been decisive at the beginning of the war. The military coup had failed in Madrid and Barcelona, Spain's principal cities. Franco's best troops, the Foreign Legion and the Regulares, the Moorish mercenaries recruited to fight against their own people, were cooped up in Morocco, since the Spanish Navy had declared for the Republic. Planes and pilots from the Luftwaffe and the Italian Air Force, in the first military airlift in history, had flown some 8,000 troops across to Sevilla, Franco's base for the advance on Madrid.

And this was all I needed to make up my mind. I left a few days later for Paris, with a group of a dozen or so volunteers that John had assembled. There were three Cambridge graduates and one from Oxford (a statistic I have always been proud of), as well as one from London University. There was a German refugee artist who had been living in London, two veterans of the British Army and one of the Navy, an actor, a proletarian novelist and two unemployed workmen. Before we left, I had gone with John to visit his father in Cambridge; he was the distinguished Greek scholar Francis MacDonald Cornford, author of brilliant books on Attic comedy, Thucydides and Greek philosophy, and Plato. He had served as an officer in the Great War and still had the pistol he had had to buy when he equipped himself for France. He gave it to John, and I had to smuggle it through French Customs at Dieppe, for John's passport showed entry and exit stamps from Port-Bou and his bags were likely to be given a thorough going-over.

(13) Bernard Knox, John Cornford: A Memoir (1938)

Our baptism of fire was sharp and unexpected. We were scattered with our machine-guns along a crest which we had every reason to believe was as safe as anything could be in the Madrid area (which wasn't very safe), when we heard our first shell. Nobody minded much, because it burst a good forty yards behind us, but the next two or three showed us that they were feeling for the crest we were occupying. They got it, and then the barrage started. I remember shouting to John that we ought to go over the crest into the valley, but I don't think he heard me. A few minutes later it became apparent that nothing could remain on that crest and live, so everybody went over, pell-mell. When we sorted ourselves out down below I found that John had taken command of two machine-gun crews and brought them over with guns and ammunition complete. Our commander had gone up to advanced positions that night with one of our gun-crews, so John took over command that morning, inspecting the positions we had taken up, and criticising ruefully the way in which most of us came down the cliff. But it was not a bad performance for raw troops taken by surprise in a barrage.

Our first experience of open warfare (as distinct from the dull business of holding on at all costs in the University) was a great flanking attack on the Fascist lines at Aravaca. I remember it well because after we had been withdrawn to rest-positions after a gruelling day and night in a trench captured from the Fascists (their gunners naturally knew the range to an inch), John was the first to go up again and volunteer as an extra stretcher-bearer, to bring in the badly mangled Poles who were attacking over half a mile of completely open country under accurate shrapnel fire.

Aravaca was a costly failure - the only apparent result was the loss of the University to the Fascists in our absence. We were withdrawn immediately to retake it. And with its capture began a period when we were as happy as I think men can possibly be in the front line of a modern war. We were under cover from the deadly cold that so far had been our worst enemy, we had leisure to talk and smoke in physical comfort, and, greatest pleasure of all, it was safe to take our boots off at night. The only drawbacks to this battle paradise were the fact that we were a perfect target for artillery, and the realisation that we might be completely cut off at any moment. Here we discussed art and literature, life and death and Marxism during the long day, and as the evening drew on, we sang. Nothing delighted John more than the sort of crude community singing that is common to undergraduate parties and public bars alike. I remember the singing particularly, because my voice, bad as it is, was the only voice among us capable of holding the song fast to the proper tune.

(14) John Cornford, letter to Margot Heinemann (8th December, 1936)

The section leader, Fred Jones, was away, and so confident that all was quiet that he hadn't appointed a successor. I took charge on the moment, was able to get all the guns - we then had four - into position, and rescued one which the gunmen had deserted In a panic. But there was no attack after all.

Then in reserve in the Casa del Campo: a big wood, ex-royal forest, rather Sussexy to look at: but behind to the right a range of the Guadarama, a real good range with snow against a very blue sky. Then a piece of real bad luck. Maclaurin and three Other Lewis gunners were sent up to the front. The French infantry company they were with was surprised by the Moors. The Lewis gunners stayed to cover the retreat. Mac was found dead at his gun, Steve Yates, one of our corporals, an ex-soldier and a good bloke, was killed too. Another, wounded in the guts. It's always the best seem to get the worst.

Then for the first time up to the front. We advanced into position at exactly the wrong time, at sunset, taking over some abandoned trenches. The Fascists had the range exact and shelled us accurately. Seven were killed in a few minutes. We had a nasty night in the trenches. Then back into reserve. The main trouble now was the intense cold: and we were sleeping out without blankets, which we had left behind in order to carry more machine-gun ammunition. Worse still to come; we had to make a night march back. There was a lorry load of wounded behind us. The lorry driver signalled, but wasn't noticed and got no answer. The four lines were so indeterminate that he thought we were a Fascist column and accelerated past us. Someone put up a wire to stop the car. The wire was swept aside, caught Fred Jones by the neck, hauled him over the parapet and killed him. Fred was a really good section leader: declassed bourgeois, ex-guardsman unemployed organiser, combination of adventurer and sincere Communist: but a really powerful person and could make his group work in a disciplined way in 2.n army where there wasn't much discipline. That day the French redeemed their bad start by a really good bayonet attack which recaptured the philosophy building. We were in reserve for all this...

Well, that's how far we've got. No wars are nice, and even a revolutionary war is ugly enough. But I'm becoming a good soldier, longish endurance and a capacity for living in the present and enjoying all that can be enjoyed. There's a tough time ahead but I've plenty of strength left for it.

Well, one day the war will end - I'd give it till June or July, and then if I'm alive I'm coming back to you. I think about you often, but there's nothing I can do but say again, be happy, darling, And I'll see you again one day.

(15) John Cornford, A Letter From Aragon (1936)

This is a quiet sector of a quiet front.

We buried Ruiz in a new pine coffin,

But the shroud was too small and his washed feet stuck out.

The stink of his corpse came through the clean pine boards

And some of the bearers wrapped handkerchiefs round their faces.

Death was not dignified.

We hacked a ragged grave in the unfriendly earth

And fired a ragged volley over the grave.

You could tell from our listlessness, no one much missed him.

This is a quiet sector of a quiet front.

There is no poison gas and no H.E.3

But when they shelled the other end of the village

And the streets were choked with dust

Women came screaming out of the crumbling houses,

Clutched under one arm the naked rump of an infant.

I thought: how ugly fear is.

This is a quiet sector of a quiet front.

Our nerves are steady; we all sleep soundly.

In the clean hospital bed my eyes were so heavy

Sleep easily blotted out one ugly picture,

A wounded militiaman moaning on a stretcher,

Now out of danger, but still crying for water,

Strong against death, but unprepared for such pain.

This on a quiet front.

But when I shook hands to leave, an Anarchist worker

Said: "Tell the workers of England

This was a war not of our own making,

We did not seek it.

But if ever the Fascists again rule Barcelona

It will be as a heap of ruins with us workers beneath it."

(16) Peter Stansky & William Abrahams, Journey to the Frontier (1966)

The new campaign was intended to relieve the pressure on Madrid by a diversionary attack on Fascist territory in the South. There the Government held the province of Jaen, and the Fascists the adjoining province of Cordoba. And Cordoba, the capital city, was only eighty-two miles from the most important city in rebel hands: Seville. The objective of the Loyalist forces was to head down the valley of the Guadalquivir towards these two cities. About fifteen miles beyond Andujar, where they detrained, off the main road, was the village of Lopera, the rebels' principal outpost. Up to there the Brigade had advanced without undue difficulty, although they had been strafed by planes, and one of the Englishmen, Nat Segal, was killed, the first dead in the new draft. But now they were bogged down, so badly that at one point headquarters issued a communique saying: "During the day the advance continued without the loss of any territory." The Brigade took up positions in the olive groves around Lopera, and around another walled village, Villa del Rio, a little further along the road to Cordoba.

The commander of the 12th Battalion was a French officer, Major Lasalle, who appears to have been a coward, a fool and a rigid disciplinarian. Later he was to be shot as a Fascist spy, which he may or may not have been-there is some doubt on the charge. Lasalle was operating a good distance in the rear, and he ordered No. i Company, with whom he had had a number of quarrels during the training period, to take Lopera, promising to send up full support. In fact, he never did. Nathan, however, took him at his word, and organized several attacks on the village, none successful. On Christmas night, or after midnight on the 26th, the company got to the crest of a hill above Lopera, where they spent a miserable night in the cold. In the morning they were driven back by strafing planes that had no trouble in spotting them, since the olive groves afforded little protection or camouflage. Again and again during the next three days advances were attempted and beaten back. Nathan finally ordered his men to spread out in a long thin line along the crest. His theory, a valid one, was that if they went over the ridge, at the top of which they would make splendid targets, all at once, they would have a better chance of survival than if they went over in small groups, a few at a time. I le waited now for the support to arrive that had been promised him; he sent out scouts to watch for it. None was forthcoming; there were only repeated orders from Lasalle's messengers to attack. At last Nathan led his men with his gold-tipped swagger stick over the crest. Then they were stopped by a blaze of machine-gun fire. Hastily they began to dig in, and since they were without entrenching tools they attempted to use their tin plates as shovels. Lacking support, or effective machine-guns of their own, there was nothing more they could do. There were sections armed with modern Colt machine-guns in the battalion, but they had received no orders to participate in the attack, and were at too great a distance to be summoned. The machine-guns of No. i Company were twenty-year-old Chauchats, most of which jammed on their first shot; most of the rifles were older Austrian Steyrs which, lacking their special ammunition clip, had to be used as single shots. On the 27th the Fascists counter-attacked heavily. Nathan was left with no choice but to withdraw and join the rest of the battalion. They spent another night of cold and discomfort; neither their packs nor blankets had been sent up to them; food had to be searched for. The number of dead and wounded was already ominously large. Retreating, they had had to leave the dead where they fell, and the wounded to the mercy of the Fascists. Yet the next day, December 28, No. 1 Company attacked again, and in three advances got almost to the walls of the town. This time they were supported by French machine-gun fire, but the operation was badly co-ordinated: at one point they were under fire from their own guns. The battle went on for four hours. Lasalle was in the rear; there was no one to order the two other companies, which were available, into the assault.

Aeroplanes swooped down; the Fascist artillery and machine-gun fire mounted in intensity; the company was being decimated. Finally Nathan had to order a retreat, and leave for the last time what had come to be known as the "English crest". Among the dead left behind was John Cornford.

(17) The Cambridge Review (5th February 1937)

John Cornford was born on 27th December 1915. After an early schooling in Cambridge he went to Stowe, where at the age of sixteen he took an Open Major Scholarship to Trinity College. He came up to Cambridge in 1933.

His career in Cambridge was of exceptional brilliance. He took first-class honours in Pt. I of the Historical Tripos and a starred First in Pt. II. On graduating he was awarded the Earl of Derby Research Scholarship, which he resigned on going out to Spain. At the same time his genius for organisation, his understanding and his devotion to the cause for which he died, made him joint leader of the C.U. Communist Party, to which he belonged, and later joint-secretary of the Socialist Club. The Socialist movement in the Universities, not only in Cambridge but throughout the whole of England, owes more to him than to any other individual. He was elected twice to the Standing Committee of the Union, where his sincerity and knowledge earned him the highest respect, and his many writings included a section of the pamphlet British Arms and World Peace, articles in Christianity and Social Revolution, and New Minds for Old, and in magazines here and in America.

At the outbreak of the Spanish rebellion he had begun research work, but he saw quickly the nature and significance of the Spanish struggle, and before anyone else he realised the importance of volunteer work in the people's army. He left for Spain in early August, but after a month in Aragon, where he served as a soldier, he returned to England to form the company which later became the nucleus of the British section of the International Brigade. As a machine-gun unit they underwent five weeks of intense fighting and bombardment in Madrid, where they soon earned the reputation for exceptional bravery. John Cornford always was outstanding among them. And though at first he refused, later he was made commander at the wish of his men, who, like everyone else who worked with him, accepted him as their leader. While in University City he was wounded in the head by shrapnel, but he refused to rest, and after twenty-four hours in hospital returned to the front. Later, at Boadilla del Monte, his unit for the first time faced the massed German troops, and after heavy bombardment were forced to retreat twelve kilometres in twenty-four hours. Here, as commander, in the words of an English correspondent, he "acquitted himself magnificently," saving many lives.

In late December his unit was sent to Cordova to check the rebel advance there. There, on the 28th of December, one day after his twenty-first birthday, lie was killed in action at the head of his men. Confirmation of his death reached England one month later.

In the twenty-one years in which he lived he achieved more than many can hope to achieve in their lifetime. His death is a bitter loss to English thought as well as to the undergraduates and working class of England.

(18) Professor Ernest Barker, The Cambridge Review (5th February 1937)

I had only a brief knowledge of John Cornford, but it will never pass from my memory. He came to the last discussion class which I held; and those of us who were present at that class will remember how we listened to what he had to say. His belief in Communism was no youthful effervescence; it was a still water which ran deep. He spoke slowly and deliberately; and there was sound knowledge, as well as conviction, behind what he had to say. I often turned towards him in the course of our discussions (he was a grave listener); and I never turned in vain.

He had a first-rate mind; but he had also something greater-very much greater. He was one of those who are willing to stake heart's blood upon their convictions, turning them into a faith, and acting in the strength of their faith. One may disagree with the convictions: one can only bare the head before the testimony offered to them. I could not but think, when I heard of his death, of Lauro de Bosis-the young Italian who went to Rome in his lonely aeroplane at the beginning of the October term of 1931, delivered his testimony, and died. John Cornford went to Spain in a sober English way, with a quiet resolution; but he was of the same stuff.

I do not think, from what I knew of him, that there was any sentiment about his action; and it would be a treason to his memory to show sentiment about his death. He did what he believed to be his duty... He leaves a memory-dark hair, deep eyes, deep, slow voice: steady thought, deep conviction, and the ultimate testimony which a man can give to his conviction.