Annie Besant

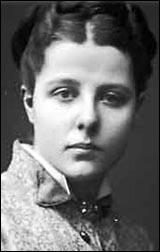

Annie Wood, the daughter of William Wood and Emily Morris Wood, was born at 2 Fish Street, London on 1st October, 1847. Annie's father, an underwriter, died when she was only five years old. Without any savings, Annie's mother found work looking after boarders at Harrow School. (1)

Mrs. Wood was unable to care for Annie and she persuaded a friend, Ellen Marryat, who lived in Charmouth in Dorset, to take responsibility for her education. Annie later recalled: "Miss Marryat had a perfect genius for teaching, and took in it the greatest delight... She taught us everything herself except music, and for this she had a master, practising us in composition, in recitation, in reading aloud English and French, and later, German, devoting herself to training us in the soundest, most thorough fashion. No words of mine can tell how much I owe her, not only of knowledge, but of that love of knowledge which has remained with me ever since as a constant spur to study." (2)

Marryat disagreed strongly with the idea of rote-learning. The children wrote about what interested them. They were also taught to think clearly. However, Marryat was "an extreme evangelical evangelical; sin, damnation, conversion, and permanent recourse to the Scriptures formed the regime". The children were forced to read both the Bible and the Fox Book of Martyrs and therefore "encouraging more daydreams of facing the stake or the rack." (3)

At the age of sixteen, Annie left the care of Miss Marryat. She was intensely devout and in her own words, "the very stuff of which fanatics were made". Annie was an attractive young woman and her "dark curls and a trim, tiny figure appeared at the Harrow balls and inspired several proposals of marriage." (4)

In April 1866 Annie met "the Rev. Frank Besant, a young Cambridge man, who had just taken orders, and was serving the little mission church as deacon" in Clapham. (5) A former schoolteacher, he was seven years older than Annie and according to one of her biographers, Anne Taylor, he was "an impecunious, parsimonious, stiff-necked young man from Portsea, whose evangelicalism was approvingly described as serious". (6)

A few months later he suddenly asked her to be his wife when he was on the point of getting on to a train: "Out of sheer weakness and fear of inflicting pain I drifted into an engagement with a man I did not pretend to love." The following year she met William Prowting Roberts, the 61-year-old, radical lawyer, who was a close friend of Ernest Jones, a Chartist and a follower of Karl Marx. Roberts, was a lawyer who had fought to improve the conditions of women and children working in the coal mines. (7)

"He (William Prowting Roberts) worked hard in the agitation which saved women from working in the mines, and I have heard him tell how he had seen them toiling, naked to the waist, with short petticoats barely reaching to their knees, rough, foul-tongued, brutalised out of all womanly decency and grace; and how he had seen little children working there too, babies of three and four set to watch a door, and falling asleep at their work to be roused by curse and kick to the unfair toil. The old man's eye would begin to flash and his voice to rise as he told of these horrors, and then his face would soften as he added that, after it was all over and the slavery was put an end to, as he went through a coal district the women standing at their doors would lift up their children to see 'Lawyer Roberts' go by, and would bid 'God bless him' for what he had done."

Roberts had a major impact on Annie's political views. "This dear old man was my first tutor in Radicalism, and I was an apt pupil. I had taken no interest in politics, but had unconsciously reflected more or less the decorous Whiggism which had always surrounded me. I regarded the poor as folk to be educated, looked after, charitably dealt with, and always treated with most perfect courtesy, the courtesy being due from me, as a lady, to all equally, whether they were rich or poor. But to Mr. Roberts the poor were the working-bees, the wealth producers, with a right to self-rule not to looking after, with a right to justice, not to charity, and he preached his doctrines to me in season and out of season." (8)

Marriage

Annie Wood married Frank Besant in Hastings on 21st December, 1867. It was a very unhappy marriage: "Frank Besant seems to have been rigid, charmless and entirely set in his belief that a husband's word is law within his household; Annie was delicate and intellectual and cosseted... It is curious that, believing marriage to be the one and only destiny of women. Victorian families so often sent their daughters into it not only sexually ignorant but ignorant of housekeeping and money management." (9)

Annie Besant admitted many years later that she had made a terrible mistake marrying Frank Besant. "In truth, I ought never to have married, for under the soft, loving, pliable girl there lay hidden, as much unknown to herself as to her surroundings, a woman of strong dominant will, strength that panted for expression and rebelled against restraint, fiery and passionate emotions that were seething under compression - a most undesirable partner to sit in the lady's armchair on the domestic rug before the fire". (10)

By the time she was twenty-three Annie had two children, Digby (16th January 1869) and Mabel (28th August 1870). Annie had difficult births and when she suggested to her husband that they should try "family limitation" he gave her a beating. "On various occasions he threw her over a stile, kneed her and pushed her out of bed so that she crashed on the floor and was badly bruised." (11)

However, Annie was deeply unhappy because her independent sprit clashed with the traditional views of her husband. Annie also began to question her religious beliefs. In 1872 she heard the eloquent sermons of Charles Voysey, who was a leading Dissenter preacher. Voysey, who was considered to be a theist, denied the perfection of Jesus and the authority of the Bible. Annie sought Voysey's advice on religious matters and "struck by the unusual appearance and earnestness of this beautiful woman of twenty-five", he invited her to his home in Dulwich. (12)

Voysey introduced Annie to Thomas Scott, a sixty-four year-old freethinker. "At that time Thomas Scott was an old man, with beautiful white hair, and eyes like those of a hawk gleaming from under shaggy eyebrows. He had been a man of magnificent physique, and, though his frame was then enfeebled, the splendid lion-like head kept its impressive strength and beauty, and told of a unique personality. Well born and wealthy, he had spent his earlier life in adventure in all parts of the world, and after his marriage he had settled down at Ramsgate, and had made his home a centre of heretical thought." (13)

Scott was impressed with Annie Besant and invited her to write a pamphlet on her religious views. She agreed to his request and Scott published, On the Deity of Jesus of Nazareth: An Inquiry into the Nature of Jesus, in March 1873. Frank Besant became aware of this pamphlet and issued an ultimatum: Annie was to be seen to take holy communion regularly at his church or she was to leave the family home. Annie later recalled that she chose "expulsion" over "hypocrisy". In October, 1873, she signed a deed of separation that allowed her to keep Mabel with her, but had to leave Digby, aged four, with his father. (14)

Annie Besant and Charles Bradlaugh

Annie Besant found temporary work as a governess in Folkstone. However, in 1874 her mother became ill and so she rented a house in Upper Norwood so she could look after her. Emily Wood died on 10th May. During this period she produced pamphlets for Thomas Scott. In addition to the payment she received for this work, she was also welcome to take meals at Scott's house. She later recalled that he was the first man outside her family whom she could truthfully say she loved." (15)

In July 1874, Annie purchased a copy of the The National Reformer. The newspaper had been established by Charles Bradlaugh and Joseph Barker. They believed that religion was blocking progress and advocated what they called an atheistic Secularism. The newspaper advocated a whole range of reforms including universal suffrage and republicanism. Bradlaugh had also helped establish the National Secular Society. (16)

Annie Besant later pointed out: "Attracted by the title, I bought it. I read it placidly in the omnibus on my way to Victoria Station, and found it excellent, and was sent into convulsions of inward merriment when, glancing up, I saw an old gentleman gazing at me, with horror speaking from every line of his countenance. To see a young woman, respectably dressed in crape, reading an Atheistic journal, had evidently upset his peace of mind, and he looked so hard at the paper that I was tempted to offer it to him, but repressed the mischievous inclination". (17)

Annie decided to write to the newspaper and asked if "it was necessary for a person to profess Atheism before being admitted to the National Secular Society". Bradlaugh replied that anyone could join "without being required to avow himself an Atheist". However, he added: "Candidly, we can see no logical resting-place between the entire acceptance of authority, as in the Roman Catholic Church, and the most extreme Rationalism." (18)

Annie attended her first National Secular Society on 2nd August, 1874. "The Hall was crowded to suffocation, and, at the very moment announced for the lecture, a roar of cheering burst forth, a tall figure passed swiftly up the Hall to the platform, and, with a slight bow in answer to the voluminous greeting, Charles Bradlaugh took his seat. I looked at him with interest, impressed and surprised. The grave, quiet, stern, strong face, the massive head, the keen eyes, the magnificent breadth and height of forehead - was this the man I had heard described as a blatant agitator, an ignorant demagogue?"

Bradlaugh than began his lecture: "He began quietly and simply, tracing out the resemblances between the Krishna and the Christ myths, and as he went from point to point his voice grew in force and resonance, till it rang round the hall like a trumpet. Familiar with the subject, I could test the value of his treatment of it, and saw that his knowledge was as sound as his language was splendid. Eloquence, fire, sarcasm, pathos, passion, all in turn were bent against Christian superstition, till the great audience, carried away by the torrent of the orator's force, hung silent, breathing soft, as he went on, till the silence that followed a magnificent peroration broke the spell, and a hurricane of cheers relieved the tension". (19)

In 1874 Bradlaugh was forty, whereas Annie was twenty-six. He was at the height of his powers and was considered to be one of the most outstanding orators in the country. Henry Snell was one of those impressed with Bradlaugh's oratory: "Bradlaugh was already speaking when I arrived, and I remember, as clearly as though it were only yesterday, the immediate and compelling impression made upon me by that extraordinary man. I have never been so influenced by a human personality as I was by Charles Bradlaugh. The commanding strength, the massive head, the imposing stature, and the ringing eloquence of the man fascinated me... and I became one of his humblest but most devoted of his followers." (20)

Tom Mann was a young trade unionist when he first heard Bradlaugh speak: "Charles Bradlaugh was at this period, and I think for fully fifteen years, the foremost platform man in Britain. When championing an unpopular cause, it is of advantage to have a powerful physique. Bradlaugh had this; he had also the courage equal to any requirement, a command of language and power of denunciation superior to any other man of his time... He was a thorough-going Republican. Of course, in theological affairs, he was the iconoclast, the breaker of images." (21)

Annie Besant soon became close friends with Charles Bradlaugh. A few days after their first meeting Bradlaugh offered her a job on his newspaper. "It was only a weekly salary of a guinea but it was a welcome addition to my resources". She also accepted Bradlaugh's invitation to give public lectures on subjects that she felt strongly about. In August 1874 she gave a talk entitled "The Political Status of Women" at the Co-operative Institute in London. (22)

In her autobiography Annie Besant pointed out that she was seized by nerves right up to the moment of going on to the platform: "But to my surprise all this miserable feeling vanished the moment I was on my feet and was looking at the faces before me. I felt no tremor of nervousness from the first word to the last, and as I heard my own voice ring out over the attentive listeners I was conscious of power and of pleasure, not of fear. And from that day to this my experience has been the same; before a lecture I am horribly nervous, wishing myself at the ends of the earth, heart beating violently, and sometimes overcome by deadly sickness." (23)

Bradlaugh's daughter commented: "She was very fluent, with a great command of language, and her voice carried well; her throat, weak at first, rapidly gained in strength, until she became a most forcible speaker. Tireless as a worker, she could both write and study longer without rest and respite than any other person I have known; and such was her power of concentration, that she could work under circumstances which would have confounded almost every other person. Though not an original thinker, she had a really wonderful power of absorbing the thoughts of others, of blending them, and of transmuting them into glowing language. Her industry, her enthusiasm, and her eloquence made of her a very powerful ally to whatever cause she espoused." (24)

Annie Besant developed a reputation as an outstanding public speaker. The Irish journalist, T. P. O'Connor wrote: "What a beautiful and attractive and irresistible creature she was then’with her slight but full and well-shaped figure, her dark hair, her finely chiseled features… with that short upper lip that seemed always in a pout". (25) Beatrice Webb claimed that she was the "only woman I have ever known who is a real orator, who has the gift of public persuasion." However, she added that to "see her speaking made me shudder, it is not womanly to thrust yourself before the world." (26)

Tom Mann agreed: "The first time I heard Mrs. Besant was in Birmingham, about 1875. The only women speakers I had heard before this were of mediocre quality. Mrs. Besant transfixed me; her superb control of voice, her whole-souled devotion to the cause she was advocating, her love of the down-trodden, and her appeal on behalf of a sound education for all children, created such an impression upon me, that I quietly, but firmly, created such an impression upon me, that I quietly, but firmly, resolved that I would ascertain more correctly the why and wherefore of her creed." (27)

Annie and Bradlaugh became very close but they never lived together. Bradlaugh had separated from his wife but he was devoted to his two teenaged daughters, Alice and Hypatia, and was reluctant to upset them by setting up home with Annie. Friends believe that Annie was also unwilling to live with Bradlaugh while she was still officially married to Frank Besant, who was unwilling to give her a divorce. (28)

Hypatia Bradlaugh later recalled: "They were mutually attracted; and a friendship sprang up between them of so close a nature that had both been free it would undoubtedly have ended in marriage. In their common labours, in the risks and responsibilities jointly undertaken, their friendship grew and strengthened, and the insult and calumny heaped upon them only served to cement the bond". (29)

As Annie Besant and Charles Bradlaugh were atheists and republicans they came under constant attack from the newspapers. One described her as "the devil of Atheistic Freethought" and others accused the couple of believing in "free love" and the "destruction of the marriage tie". A local newspaper in Essex referred to "that bestial man and woman who go about earning a livelihood by corrupting the young of England". These accusations "horrified her Victorian conscience". Annie commented "I found myself held up to hatred as an upholder of views that I abhorred." (30)

In reality Bradlaugh "abhorred free love as much as he worshipped free thought". (31) According to Theodore Besterman: "There is not doubt that if they had been free Bradlaugh and Mrs Besant would have married. As it was they neither of them had the wish to indulge in an intrigue, which would, moreover, in their position, have been fatal to both of them." Another friend, Sri Prakasa, claimed that Annie Besant "was the one person who was capable of the deepest feelings without any thought of sex; and she was a woman of such remarkable courage that when she was working with colleagues she did not care what the world thought of her." (32)

The Fruits of Philosophy

In 1832, Charles Knowlton, a doctor from Ashfield, Massachusetts, published a small pamphlet, The Fruits of Philosophy. It contained a summary of what was then known about the physiology of conception, listed a number of methods to treat infertility and impotence, and explained three methods of birth control, including a new system he had developed, that involved using a syringe to wash out the vagina after intercourse with "a solution of sulphate of zinc, of alum, pearl-ash, or any salt that acts chemically on the semen". Knowlton was arrested and was sent to prison for three months. (33)

It was also published in Britain and over the next forty years it sold in very small numbers. A new edition was published in Bristol in December 1876, by a bookseller, Henry Cook. He was arrested and charged with publishing pornography. Cook was found guilty, and sentenced to two years' imprisonment. Charles Watts and his wife, Kate Watts, both members of the National Secular Society, decided to withdraw the pamphlet for sale in their shop in London. (34)

Annie Besant and Charles Bradlaugh disagreed with this decision and decided to establish the Freethought Publishing Company so they could publish a sixpenny edition of the pamphlet. (35) They started a major publicity campaign and on publication day, 24th March, 1877, they sold over 500 pamphlets from their small office in the first twenty minutes of it being available. A police detective was among the purchasers. (36).

Annie wrote a preface which explained why she thought the pamphlet should be published. She referred to the Richard Carlile case in 1826 when he published Every Woman's Book. Annie stated they hoped that they could "carry on Carlile's work", a book "which argued for a rational approach to birth control, attacking the Christian demonization of sexual desire while denying the traditional chauvinist assumptions about women". (37)

Annie Besant added that she agreed with Thomas Malthus "that population has a tendency to increase faster than the means of existence". Annie pointed out that Britain population had nearly doubled during the first half of the 19th century, growing from 11 million in 1801 to 21 million in 1851. As a result their was "enormous mortality among infants of the poor is one of the checks which now keeps down the population".

Annie went on to argue: "We think it more moral to prevent the conception of children than, after they are born, to murder them by want of food, air, and clothing. We advocate scientific checks to population, because, so long as poor men have large families, pauperism is a necessity, and from pauperism grow crime and disease. The wage which would support the parents and two or three children in comfort and decency is utterly insufficient to maintain a family of twelve or fourteen, and we consider it a crime to bring into the world human beings doomed to misery or to premature death". (38)

Besant and Bradlaugh were arrested and appeared in court on 18th June, 1877. They were prosecuted by the Solicitor-General of the Conservative government, Hardinge Giffard, for publishing "a certain indecent, lewd, filthy, bawdy, and obscene book". They were to be charged under the 1857 Obscene Publications Act that stated that "the test of obscenity is to deprave and corrupt those whose minds are open to such immoral influences, and into whose hands a publication of this sort may fall."

Giffard argued: "The truth is, those who publish this book must have known perfectly well that an unlimited publication of this sort, put into the hands of everybody, whatever their age, whatever their condition in life, whatever their modes of life, whatever their means, put into the hands of any person who may think proper to pay sixpence for it - the thesis is this: if you do not desire to have children, and wish to gratify your sensual passions, and not undergo the responsibility of marriage... It is sought to be justified upon the ground that it is only a recommendation to married people, who under the cares of their married life are unable to bear the burden of too many children. I should be prepared to argue before you that if confined to that object alone it would be most mischievous.... I deny this, and I deny that it is the purport and intention of this book." (39)

Annie Besant later recorded in Autobiographical Sketches (1885) that Giffard used the case to attack the Liberal Party: "The Solicitor-General made a bitter and violent speech, full of party hate and malice, endeavoring to prejudice the jury against the work by picking out bits of medical detail and making profound apologies for reading them, and shuddering and casting up his eyes with the skill of a finished actor." (40)

Annie Besant represented herself in court. She pointed out that in 1876 only 700 copies of The Fruits of Philosophy had been purchased in Britain. However, in the three months before the trial 125,000 had been sold. "My clients are scattered up and down through the length and breadth of the land; I find them amongst the poor, amongst whom I have been so much; I find my clients amongst the fathers, who see their wage ever reducing, and prices ever rising... Gentlemen, do you know the fate of so many of these children? The little ones half starved because there is food enough for two but not enough for twelve; half clothed because the mother, no matter what her skill and care, cannot clothe them with the money brought home by the breadwinner of the family; brought up in ignorance, and ignorance means pauperism and crime." (41)

The following day in court Annie Besant illustrated the problems faced by having large families. She quoted Henry Fawcett as "children belonging to the upper and middle classes 20 per cent die before they reach the age of five"; and he adds that the amount is more than doubled in the case of children belonging to the labouring classes. "This great mortality amongst poor children is caused by neglect, by want of proper food, and by unwholesome dwellings. When we take these facts, and find that this large number of children have literally been murdered, when you consider that the number of these children who, if they had been born in a higher rank, would not have died, is calculated by Professor Fawcett as 1,150,000."

Annie Besant talked of the evils of prostitution. She believed that this problem would be reduced if young men and women married early: "I say that men and women will marry young - in the flower of their age - and more especially will this be the case amongst the poorer classes... I cannot go to the poor man, and tell him that the brightest part of his life is to be spent alone, and that he is to be shut out for years from the comforts of a home and the happiness of married life... There is no talk in this book of preventing men and women from becoming parents; all that is sought here is to limit the number of their family. And we do not aim at that because we do not love children, but, on the contrary, because we do love them, and because we wish to prevent them from coming into the world in greater numbers than there is the means of properly providing for." (42)

The prosecutor, Hardinge Giffard, had claimed that the pamphlet was obscene because it described and illustrated "male organs of generation". However, as she pointed out, boys and girls under sixteen in government schools were using textbooks that included details of "sexual reproduction" that were much more graphic than in her pamphlet. She asked if there were any plans to prosecute the publishers of these school textbooks? (43)

Besant pointed out that her doctor provided her with a book written by Pye Henry Chavasse, entitled Advice to a Mother on the Management of Her Children and on the Treatment on the Moment of Some of Their More Pressing Illnesses and Accidents (1868). "When I was first married my own doctor gave me the work of Chavasse, on the ground that it was better for a woman to read the medical details than it was for her to have to apply to one of the opposite sex to settle matters which did not need to be dealt with by the doctor." Besant suggested that the advice given in this book was very similar to that of her own pamphlet. The difference was that Chavasse's book was expensive whereas her pamphlet cost only sixpence. (44)

Charles Bradlaugh also carried out his own defence. He looked very closely at the economics of birth-control. "The best paid class of hewers of coal are not now averaging much more than one pound a week; take that for a man and his wife and three children only. But suppose him to have five. The Pauper Unions allow 4s 6d a week, and sometimes a little more, for boarding out a pauper child. Suppose the coalhewer has a family of five, six or seven - do the multiplication for yourselves, and leave nothing for luxury or dissipation on the part of the bread winner - I ask what means has he of purchasing the expensive treatises from which I shall quote? I now submit that it is impossible to advocate sexual restraint after marriage amongst the poor without such medical or physiological instructions as may enable them to comprehend the advocacy and utilise it." (45)

Bradlaugh argued that using birth-control was a moral act when compared to the alternatives. He claimed that in 1868 more than 16,000 women in London "murdered their offspring". He argued, "it is amongst the poor married people that the evils of over-population are chiefly felt", and, he maintained, "the advocacy of every birth-restricting check is lawful except such as advocate the destruction of the foetus after conception or of the child after birth", and that this advocacy "to be useful must of necessity be put in the plainest language and in the cheapest form". (46)

Alice Vickery, a nurse in London, gave evidence for the defence. She told the court "that a very great deal of suffering is caused by over-childbearing to the mothers themselves; to the children, because of the insufficient nutriment which they are able to give them and to the children before birth from the condition of the mothers." She went on to claim that mothers breast-fed their babies in an attempt to stop them getting pregnant again. "I have known many women who have continued to suckle their children as long as two years, and even longer than two years, because they believed that that would prevent them from conceiving again so rapidly." This caused serious health problems for the mothers and their babies. (47)

Dr. Charles Robert Drysdale, Senior Physician, Metropolitan Free Hospital, also defended the actions of Annie Besant and Charles Bradlaugh. He talked in court about the medical problems caused by large families. "I have been continually obliged to lament the excessive rapidity with which the poorer classes bring unfortunate children into the world, who, in consequence, grow up weak and ricketty.... When a working man marries, the first child or two look very healthy, whilst the third will look ricketty because the mother is not able to give them that proper nourishment which she lacks herself. And so with both the fourth and fifth.... When three or four are born they get that terrible disease-the rickets - which is a great cause of death in London, a much greater cause than is generally supposed.... Hence the death-rate is largest in large families."

Drysdale then went on to look at the death-rate in London: "One fact I will mention to draw the attention of yourself and the jury to the very important point of infant mortality.... With all our advances in science we have not been able to decrease the general death-rate in London. Twenty years ago it was 22.2 per thousand persons living. In I876 it was almost exactly the same, being, in fact 22.3. Instead of dying more slowly than we did twenty years ago, we die a little faster.... The real reason of this increase in the death-rate is, that the children of the poor die three times as fast as the children of the rich... In 100,000 children of the richer classes, it was found that there were only 8,000 who died during the first year of life; whereas looking at the Registrar-General's returns we find that 15,000 out of every 1,000 of the general population die in their first year. If you take the children of the poor in the towns you will find the death-rate three times as large as among the rich - instead of 8,000 there would be 24,000 among the children of the poor. So that you see, the children of the poor are simply brought into the world to be murdered". (48)

In his final statement in court Hardinge Giffard argued: "I say that this is a dirty, filthy book, and the test of it is that no human being would allow that book to lie on his table; no decently educated English husband would allow even his wife to have it, and yet it is to be told to me, forsooth, that anybody may have this book in the City of London or elsewhere, who can pay sixpence for it! The object of it is to enable persons to have sexual intercourse, and not to have that which in the order of Providence is the natural result of that sexual intercourse." (49)

The jury ruled: "We are unanimously of opinion that the book in question is calculated to deprave public morals, but at the same time we entirely exonerate the defendants from any corrupt motives in publishing it." The Lord Chief Justice told the jury that the statement was unacceptable and "I must direct you on that finding, to return a verdict of guilty under this indictment against the defendants". He then turned towards Besant and Bradlaugh and said "under these circumstances, I will not pronounce sentence against you at present." (50)

The judge eventually sentenced both of them to six months in prison and a fine of £200. However, for a sum of £500 they were allowed to have their freedom until the case appeared before the Court of Appeal. This took place in February 1878 before Lord George Bramwell, Lord William Brett and Lord Henry Cotton. They decided that the case against them was deeply flawed and the sentence was quashed. (51)

After the court-case Besant wrote and published her own book advocating birth control entitled The Laws of Population. The idea of a woman advocating birth-control received wide-publicity. Newspapers like The Times accused Besant of writing "an indecent, lewd, filthy, bawdy and obscene book". Frank Besant used the publicity of the case to persuade the courts that he, rather than Annie Besant, should have custody of their daughter Mabel. (52)

Charles Bradlaugh and the House of Commons

Charles Bradlaugh was a member of the Liberal Party and in the 1880 General Election he won the seat of Northampton. At this time the law required in the courts and oath from all witnesses. Bradlaugh saw this an opportunity to draw attention to the fact that "atheists were held to be incapable of taking a meaningful oath, and were therefore treated as outlaws." (53)

Bradlaugh argued that the 1869 Evidence Amendment Act gave him a right he asked for permission to affirm rather than take the oath of allegiance. The Speaker of the House of Commons refused this request and Bradlaugh was expelled from Parliament. William Gladstone supported Bradlaugh's right to affirm, but as he had upset a lot of people with his views on Christianity, the monarchy and birth control and when the issue was put before Parliament, MPs voted to support the Speaker's decision to expel him. (54)

Bradlaugh now mounted a national campaign in favour of atheists being allowed to sit in the House of Commons. Bradlaugh gained some support from some Nonconformists but he was strongly opposed by the Conservative Party and the leaders of the Anglican and Catholic clergy. When Bradlaugh attempted to take his seat in Parliament in June 1880, he was arrested by the Sergeant-at-Arms and imprisoned in the Tower of London. Benjamin Disraeli, leader of the Conservative Party, warned that Bradlaugh would become a martyr and it was decided to release him. (55)

On 26th April, 1881, Charles Bradlaugh was once again refused permission to affirm. William Gladstone promised to bring in legislation to enable Bradlaugh to do this, but this would take time. Bradlaugh was unwilling to wait and when he attempted to take his seat on 2nd August he was once forcibly removed from the House of Commons. Bradlaugh and his supporters organised a national petition and on 7th February, 1882, he presented a list of 241,970 signatures calling for him to be allowed to take his seat. However, when he tried to take the Parliamentary oath, he was once again removed from Parliament. (56)

The authorities attempted to obstruct the activities of Charles Bradlaugh and other freethinkers in the National Secular Society. Pamphlets on religion were seized by the Post Office and on several occasions they were excluded from using public buildings for their meetings. In 1882 the staff of the journal, The Freethinker, were prosecuted for blasphemy, and two of them were found guilty and sent to prison. (57)

Gladstone's Affirmation Bill was discussed by Parliament in the spring of 1883. The Archbishop of Canterbury and Cardinal Manning, head of the Catholic Church, argued against the right of atheists to be MPs and when the vote was taken in May 1883, the Affirmation Bill was defeated. In 1884 Bradlaugh was once again elected to represent Northampton in the House of Commons. He took his seat and voted three times before he was excluded. He was later fined £1,500 for voting illegally.

Socialism

Annie Besant became a socialist and started working with people such as Walter Crane, Edward Aveling and George Bernard Shaw. This upset Bradlaugh, who regarded socialism as a disruptive foreign doctrine that was based on the idea of violent revolution. This he expressed powerfully in his debate with H. M. Hyndman, the leader of the Social Democratic Federation, in April 1884. Bradlaugh argued that as a member of the Liberal Party he believed the way forward was for the government to pass legislation to protect those suffering from poverty.

"We recognise the most serious evils, and especially in large centres of population; arising out of the poverty already existing, aggravating and intensifying the crime, disease, and misery developed from it.... I want to remedy the evil, attacking it in detail by the action of the individuals most affected by it... Social reform is one thing because it is reform; Socialism is the opposite because it is revolution... Now I have said that in order to effect Socialism in this country – and I am only dealing with this country – it would require a physical-force revolution, because you would want that physical force to make all the present property-owners who are unwilling, surrender their private property to the common fund – you would want that physical force to dispossess them." (58)

In October, 1887, she told the readers of The National Reformer that she was now a socialist: "When I became co-editor of this paper I was not a Socialist; and, although I regard Socialism as the necessary and logical outcome of the Radicalism which for so many years the National Reformer has taught, still, as in avowing myself a Socialist I have taken a distinct step, the partial separation of my policy in labour questions from that of my colleague has been of my own making, and not of his, and it is, therefore, for me to go away. Over by far the greater part of our sphere of action we are still substantially agreed, and are likely to remain so. But since, as Socialism becomes more and more a question of practical politics, differences of theory tend to produce differences in conduct; and since a political paper must have a single editorial programme in practical politics, it would obviously be most inconvenient for me to retain my position as co-editor. I therefore resume my former position as contributor only, thus clearing the National Reformer of all responsibility for the views I hold." (59)

Ben Tillett was a young socialist who saw her speak in London in 1887: "Mrs. Besant joined the Fabian Society very shortly after its creation, and was one of the famous group who formulated the principles of English Socialism. Her remarkable qualities as a woman, and her gifts as an orator, speedily made her a prominent figure in the East End of London, when she appeared amongst us. She spoke at our organizing meetings on several occasions. One meeting, I remember, was held in a thick fog which blotted out the faces and forms of the audience, which nevertheless stayed within hearing of Mrs. Besant's superb voice, spellbound by her eloquence and social passion". (60)

Annie Besant joined the Social Democratic Federation and the Fabian Society. She became close to George Bernard Shaw who based the character, Raina Petkoff, in Arms and Man on Annie. A legal marriage was not possible because Frank Besant would not give her a divorce. She responded to his invitation to cohabit by producing a list of her terms for his signature. Apparently, Shaw exploded in laughter: "Good God! This is worse than all the vows of all the churches on earth. I had rather be legally married to you ten times over." (61)

The 1888 London Matchgirls Strike

In 1887 Besant joined forces with William Stead to establish the newspaper, The Link. The halfpenny weekly carried on its front page a quotation from Victor Hugo: "I will speak for the dumb. I will speak of the small to the great and the feeble to the strong... I will speak for all the despairing silent ones." The newspaper campaigned against "sweated labour, extortionate landlords, unhealthy workshops, child labour and prostitution." (62)

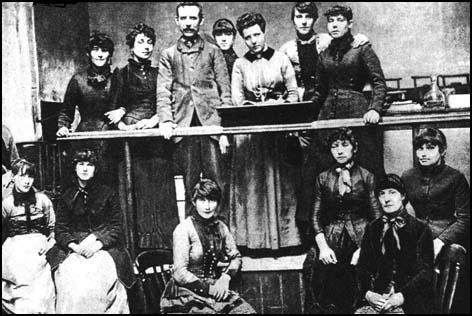

In June 1888, Clementina Black gave a speech on Female Labour at a Fabian Society meeting in London. Annie Besant, a member of the audience, was horrified when she heard about the pay and conditions of the women working at the Bryant & May match factory. The next day, Besant went and interviewed some of the people who worked at Bryant & May. She discovered that the women worked fourteen hours a day for a wage of less than five shillings a week. However, they did not always received their full wage because of a system of fines, ranging from three pence to one shilling, imposed by the Bryant & May management. Offences included talking, dropping matches or going to the toilet without permission. The women worked from 6.30 am in summer (8.00 in winter) to 6.00 pm. If workers were late, they were fined a half-day's pay. (63)

Annie Besant also discovered that the health of the women had been severely affected by the phosphorus that they used to make the matches. This caused yellowing of the skin and hair loss and phossy jaw, a form of bone cancer. The whole side of the face turned green and then black, discharging foul-smelling pus and finally death. Although phosphorous was banned in Sweden and the USA, the British government had refused to follow their example, arguing that it would be a restraint of free trade. (64)

On 23rd June 1888, Besant wrote an article in her newspaper, The Link. The article, entitled White Slavery in London, complained about the way the women at Bryant & May were being treated. The company reacted by attempting to force their workers to sign a statement that they were happy with their working conditions. When a group of women refused to sign, the organisers of the group was sacked. The response was immediate; 1400 of the women at Bryant & May went on strike. (65)

William Stead, the editor of the Pall Mall Gazette, Henry Hyde Champion of the Labour Elector and Catharine Booth of the Salvation Army joined Besant in her campaign for better working conditions in the factory. So also did Hubert Llewellyn Smith, Sydney Oliver, Stewart Headlam, Hubert Bland, Graham Wallas and George Bernard Shaw. However, other newspapers such as The Times, blamed Besant and other socialist agitators for the dispute. "The pity is that the matchgirls have not been suffered to take their own course but have been egged on to strike by irresponsible advisers. No effort has been spared by those pests of the modern industrialized world to bring this quarrel to a head." (66)

Besant, Stead and Champion used their newspapers to call for a boycott of Bryant & May matches. The women at the company also decided to form a Matchgirls' Union and Besant agreed to become its leader. After three weeks the company announced that it was willing to re-employ the dismissed women and would also bring an end to the fines system. The women accepted the terms and returned in triumph. The Bryant & May dispute was the first strike by unorganized workers to gain national publicity. It was also successful at helped to inspire the formation of unions all over the country. (67)

The trade union leader, Henry Snell, wrote several years later: These courageous girls had neither funds, organizations, nor leaders, and they appealed to Mrs. Besant to advise and lead them. It was a wise and most excellent inspiration.... The number affected was quite small, but the matchgirls' strike had an influence upon the minds of the workers which entitles it to be regarded as one of the most important events in the history of labour organisation in any country. (68)

Fabian Society

In 1889 contributed to the influential book, Fabian Essays. As well as Besant, the book included articles by George Bernard Shaw, Sydney Webb, Sydney Olivier, Graham Wallas, William Clarke and Hubert Bland. Edited by Shaw, the book sold 27,000 copies in two years.

Shaw claims that "Annie Besant... was a sort of expeditionary force, always to the front when there was trouble and danger, carrying away audiences for us when the dissensions in the movement brought our policy into conflict with that of the other societies, founding branches for us throughout the country, dashing into the great strikes and free speech agitations." (69)

In 1889 Annie Besant was elected to the London School Board in Tower Hamlets. After heading the poll with a fifteen thousand majority over the next candidate, Besant argued that she had been given a mandate for large-scale reform of local schools. Some of her many achievements included a programme of free meals for undernourished children and free medical examinations for all those in elementary schools. (70)

Theosophy

In the 1890s Annie Besant became a supporter of Theosophy, a religious movement founded by Helena Blavatsky in 1875. Theosophy was based on Hindu ideas of karma and reincarnation with nirvana as the eventual aim. Besant went to live in India but she remained interested in the subject of women's rights. She continued to write letters to British newspapers arguing the case for women's suffrage and in 1911 was one of the main speakers at an important NUWSS rally in London.

While in India, Annie joined the struggle for Indian Home Rule, and during the First World War was interned by the British authorities.

Annie Besant died in India on 20th September 1933.

Primary Sources

(1) Annie Besant, Annie Besant: An Autobiography (1908)

Miss Marryat - the favourite sister of Captain Marryat, the famous novelist - was a maiden lady of large means. She had nursed her brother through the illness that ended in his death, and had been living with her mother at Wimbledon Park. On her mother's death she looked round for work which would make her useful in the world, and finding that one of her brothers had a large family of girls, she offered to take charge of one of them, and to educate her thoroughly. Chancing to come to Harrow, my good fortune threw me in her way, and she took a fancy to me and thought she would like to teach two little girls rather than one. Hence her offer to my mother.

Miss Marryat had a perfect genius for teaching, and took in it the greatest delight. From time to time she added another child to our party, sometimes a boy, sometimes a girl. At first, with Amy Marryat and myself, there was a little boy, Walter Powys, son of a clergyman with a large family, and him she trained for some years, and then sent him on to school admirably prepared. She chose "her children" - as she loved to call us - in very definite fashion. Each must be gently born and gently trained, but in such position that the education freely given should be a relief and aid to a slender parental purse. It was her delight to seek out and aid those on whom poverty presses most heavily, when the need for education for the children weighs on the proud and the poor. "Auntie" we all called her, for she thought "Miss Marryat" seemed too cold and stiff. She taught us everything herself except music, and for this she had a master, practising us in composition, in recitation, in reading aloud English and French, and later, German, devoting herself to training us in the soundest, most thorough fashion. No words of mine can tell how much I owe her, not only of knowledge, but of that love of knowledge which has remained with me ever since as a constant spur to study.

Her method of teaching may be of interest to some, who desire to train children with least pain, and the most enjoyment to the little ones themselves. First, we never used a spelling-book - that torment of the small child - nor an English grammar. But we wrote letters, telling of the things we had seen in our walks, or told again some story we had read; these childish compositions she would read over with us, correcting all faults of spelling, of grammar, of style, of cadence; a clumsy sentence would be read aloud, that we might hear how unmusical it sounded, an error in observation or expression pointed out. Then, as the letters recorded what we had seen the day before, the faculty of observation was drawn out and trained. "Oh, dear! I have nothing to say!" would come from a small child, hanging over a slate. "Did you not go out for a walk yesterday?" Auntie would question. "Yes," would be sighed out; "but there's nothing to say about it." "Nothing to say! And you walked in the lanes for an hour and saw nothing, little No-eyes? You must use your eyes better to-day." Then there was a very favourite "lesson," which proved an excellent way of teaching spelling. We used to write out lists of all the words we could think of which sounded the same but were differently spelt. Thus: "key, quay," "knight, night," and so on, and great was the glory of the child who found the largest number. Our French lessons - as the German later - included reading from the very first. On the day on which we began German we began reading Schiller's "Wilhelm Tell," and the verbs given to us to copy out were those that had occurred in the reading. We learned much by heart, but always things that in themselves were worthy to be learned. We were never given the dry questions and answers which lazy teachers so much affect. We were taught history by one reading aloud while the others worked - the boys as well as the girls learning the use of the needle. "It's like a girl to sew," said a little fellow, indignantly, one day. "It is like a baby to have to run after a girl if you want a button sewn on," quoth Auntie. Geography was learned by painting skeleton maps - an exercise much delighted in by small fingers - and by putting together puzzle maps, in which countries in the map of a continent, or counties in the map of a country, were always cut out in their proper shapes. I liked big empires in those days; there was a solid satisfaction in putting down Russia, and seeing what a large part of the map was filled up thereby.

(2) Annie Besant, Annie Besant: An Autobiography (1908)

I sent my name in as an active member, and find it is recorded in the National Reformer of August 9th. Having received an intimation that Londoners could receive their certificates at the Hall of Science from Mr. Bradlaugh on any Sunday evening, I betook myself thither, and it was on August 2, 1874, that I first set foot in a Freethought hall. The Hall was crowded to suffocation, and, at the very moment announced for the lecture, a roar of cheering burst forth, a tall figure passed swiftly up the Hall to the platform, and, with a slight bow in answer to the voluminous greeting, Charles Bradlaugh took his seat. I looked at him with interest, impressed and surprised. The grave, quiet, stern, strong face, the massive head, the keen eyes, the magnificent breadth and height of forehead - was this the man I had heard described as a blatant agitator, an ignorant demagogue?

He began quietly and simply, tracing out the resemblances between the Krishna and the Christ myths, and as he went from point to point his voice grew in force and resonance, till it rang round the hall like a trumpet. Familiar with the subject, I could test the value of his treatment of it, and saw that his knowledge was as sound as his language was splendid. Eloquence, fire, sarcasm, pathos, passion, all in turn were bent against Christian superstition, till the great audience, carried away by the torrent of the orator's force, hung silent, breathing soft, as he went on, till the silence that followed a magnificent peroration broke the spell, and a hurricane of cheers relieved the tension.

He came down the Hall with some certificates in his hand, glanced round, and handed me mine with a questioning "Mrs. Besant?" Then he said, referring to my question as to a profession of Atheism, that he would willingly talk over the subject of Atheism with me if I would make an appointment, and offered me a book he had been using in his lecture. Long afterwards I asked him how he knew me, whom he had never seen, that he came straight to me in such fashion. He laughed and said he did not know, but, glancing over the faces, he felt sure that I was Annie Besant.

From that first meeting in the Hall of Science dated a friendship that lasted unbroken till Death severed the earthly bond, and that to me stretches through Death's gateway and links us together still. As friends, not as strangers, we met—swift recognition, as it were, leaping from eye to eye; and I know now that the instinctive friendliness was in very truth an outgrowth of strong friendship in other lives, and that on that August day we took up again an ancient tie, we did not begin a new one. And so in lives to come we shall meet again, and help each other as we helped each other in this. And let me here place on record, as I have done before, some word of what I owe him for his true friendship; though, indeed, how great is my debt to him I can never tell. Some of his wise phrases have ever remained in my memory. "You should never say you have an opinion on a subject until you have tried to study the strongest things said against the view to which you are inclined." "You must not think you know a subject until you are acquainted with all that the best minds have said about it." "No steady work can be done in public unless the worker study at home far more than he talks outside." "Be your own harshest judge, listen to your own speech and criticise it; read abuse of yourself and see what grains of truth are in it." "Do not waste time by reading opinions that are mere echoes of your own; read opinions you disagree with, and you will catch aspects of truth you do not readily see." Through our long comradeship he was my sternest as well as gentlest critic, pointing out to me that in a party like ours, where our own education and knowledge were above those whom we led, it was very easy to gain indiscriminate praise and unstinted admiration; on the other hand, we received from Christians equally indiscriminate abuse and hatred. It was, therefore, needful that we should be our own harshest judges, and that we should be sure that we knew thoroughly every subject that we taught. He saved me from the superficiality that my "fatal facility" of speech might so easily have induced; and when I began to taste the intoxication of easily won applause, his criticism of weak points, his challenge of weak arguments, his trained judgment, were of priceless service to me, and what of value there is in my work is very largely due to his influence, which at once stimulated and restrained.

One very charming characteristic of his was his extreme courtesy in private life, especially to women. This outward polish, which sat so gracefully on his massive frame and stately presence, was foreign rather than English—for the English, as a rule, save such as go to Court, are a singularly unpolished people—and it gave his manner a peculiar charm. I asked him once where he had learned his gracious fashions that were so un-English—he would stand with uplifted hat as he asked a question of a maidservant, or handed a woman into a carriage—and he answered, with a half-smile, half-scoff, that it was only in England he was an outcast from society. In France, in Spain, in Italy, he was always welcomed among men and women of the highest social rank, and he supposed that he had unconsciously caught the foreign tricks of manner. Moreover, he was absolutely indifferent to all questions of social position; peer or artisan, it was to him exactly the same; he never seemed conscious of the distinctions of which men make so much.

(3) Hypatia Bradlaugh Bonner, Charles Bradlaugh (1894)

They were mutually attracted; and a friendship sprang up between them of so close a nature that had both been free it would undoubtedly have ended in marriage. In their common labours, in the risks and responsibilities jointly undertaken, their friendship grew and strengthened, and the insult and calumny heaped upon them only served to cement the bond...

She (Annie Besant) was very fluent, with a great command of language, and her voice carried well; her throat, weak at first, rapidly gained in strength, until she became a most forcible speaker. Tireless as a worker, she could both write and study longer without rest and respite than any other person I have known; and such was her power of concentration, that she could work under circumstances which would have confounded almost every other person. Though not an original thinker, she had a really wonderful power of absorbing the thoughts of others, of blending them, and of transmuting them into glowing language. Her industry, her enthusiasm, and her eloquence made of her a very powerful ally to whatever cause she espoused.

(4) Dr. Charles Knowlton, The Fruits of Philosophy (1832)

In how many instances does the hard-working father, and more especially the mother, of a poor family remain slaves throughout their lives… toiling to live, and living to toil; when, if their offspring had been limited to two or three only, they might have enjoyed comfort and comparative affluence? How often is the health of the mother, giving birth every year to an infant and compelled to toil on… how often is the mother's comfort, health, nay, even her life thus sacrificed? Many women cannot give birth to healthy, living children. Is it desirable - is it moral, that such women should become pregnant?

Miss Marryat—the favourite sister of Captain Marryat, the famous novelist—was a maiden lady of large means. She had nursed her brother through the illness that ended in his death, and had been living with her mother at Wimbledon Park. On her mother's death she looked round for work which would make her useful in the world, and finding that one of her brothers had a large family of girls, she offered to take charge of one of them, and to educate her thoroughly. Chancing to come to Harrow, my good fortune threw me in her way, and she took a fancy to me and thought she would like to teach two little girls rather than one. Hence her offer to my mother.

Miss Marryat had a perfect genius for teaching, and took in it the greatest delight. From time to time she added another child to our party, sometimes a boy, sometimes a girl. At first, with Amy Marryat and myself, there was a little boy, Walter Powys, son of a clergyman with a large family, and him she trained for some years, and then sent him on to school admirably prepared. She chose "her children"—as she loved to call us—in very definite fashion. Each must be gently born and gently trained, but in such position that the education freely given should be a relief and aid to a slender parental purse. It was her delight to seek out and aid those on whom poverty presses most heavily, when the need for education for the children weighs on the proud and the poor. "Auntie" we all called her, for she thought "Miss Marryat" seemed too cold and stiff. She taught us everything herself except music, and for this she had a master, practising us in composition, in recitation, in reading aloud English and French, and later, German, devoting herself to training us in the soundest, most thorough fashion. No words of mine can tell how much I owe her, not only of knowledge, but of that love of knowledge which has remained with me ever since as a constant spur to study.

Her method of teaching may be of interest to some, who desire to train children with least pain, and the most enjoyment to the little ones themselves. First, we never used a spelling-book—that torment of the small child—nor an English grammar. But we wrote letters, telling of the things we had seen in our walks, or told again some story we had read; these childish compositions she would read over with us, correcting all faults of spelling, of grammar, of style, of cadence; a clumsy sentence would be read aloud, that we might hear how unmusical it sounded, an error in observation or expression pointed out. Then, as the letters recorded what we had seen the day before, the faculty of observation was drawn out and trained. "Oh, dear! I have nothing to say!" would come from a small child, hanging over a slate. "Did you not go out for a walk yesterday?" Auntie would question. "Yes," would be sighed out; "but there's nothing to say about it." "Nothing to say! And you walked in the lanes for an hour and saw nothing, little No-eyes? You must use your eyes better to-day." Then there was a very favourite "lesson," which proved an excellent way of teaching spelling. We used to write out lists of all the words we could think of which sounded the same but were differently spelt. Thus: "key, quay," "knight, night," and so on, and great was the glory of the child who found the largest number. Our French lessons—as the German later—included reading from the very first. On the day on which we began German we began reading Schiller's "Wilhelm Tell," and the verbs given to us to copy out were those that had occurred in the reading. We learned much by heart, but always things that in themselves were worthy to be learned. We were never given the dry questions and answers which lazy teachers so much affect. We were taught history by one reading aloud while the others worked—the boys as well as the girls learning the use of the needle. "It's like a girl to sew," said a little fellow, indignantly, one day. "It is like a baby to have to run after a girl if you want a button sewn on," quoth Auntie. Geography was learned by painting skeleton maps—an exercise much delighted in by small fingers—and by putting together puzzle maps, in which countries in the map of a continent, or counties in the map of a country, were always cut out in their proper shapes. I liked big empires in those days; there was a solid satisfaction in putting down Russia, and seeing what a large part of the map was filled up thereby.

(5) Annie Besant, preface to The Fruits of Philosophy (1877)

We believe, with the Rev Dr Malthus, that population has a tendency to increase faster than the means of existence, and that some checks must therefore exercise contra-overpopulation; the checks now exercised are semi-starvation and preventable disease; the enormous mortality among infants of the poor is one of the checks which now keeps down the population. The checks that ought to control population are scientific, and it is these which we advocate. We think it more moral to prevent the conception of children than, after they are born, to murder them by want of food, air, and clothing. We advocate scientific checks to population, because, so long as poor men have large families, pauperism is a necessity, and from pauperism grow crime and disease. The wage which would support the parents and two or three children in comfort and decency is utterly insufficient to maintain a family of twelve or fourteen, and we consider it a crime to bring into the world human beings doomed to misery or to premature death. It is not only the hard-working classes which are concerned in this question. The poor curate, the struggling man of business, the young professional man, are often made wretched for life by their inordinately large families, and their years are passed in one long battle to live; meanwhile the woman's health is sacrificed and her life embittered from the same cause. To all of these, we point the way of relief and of happiness; for the sake of these we publish what others fear to issue, and we do it, confident that if we fail the first time, we shall succeed at last, and that the English public will not permit the authorities to stifle a discussion of the most important social question which can influence a nation's welfare.

(6) Hardinge Giffard, opening statement (18th June, 1877)

The nature of the book - before I read any part of it - appears to me to be this. The writer contends that it is not an improper thing to gratify any animal passion which human nature may be susceptible of, that the gratification of the animal instincts in the commerce of the sexes produces in a great many instances an over-crowded population. The writer appears to contend that for the cure of that evil, and for the purpose of enabling persons to gratify their passions without that evil being so great as it is, and may be, in the world, it is lawful and proper, and expedient, to disseminate among the people a minute description of physical means whereby the population may be checked, that the commerce of the sexes may be permitted to continue, and that by various means which he minutely describes, the result of conception, and the consequent birth of children, may be averted....

These expressions, which you find all scattered through the book, assuming that they are meant for married persons to put a check upon undue population, I submit to you that is colourable, and the object of the whole book, the scope of this book, is to permit people, independent of marriage, to gratify their passions, independently of the checks which nature and providence have interposed.... I invite your attention to the last passage. You will observe the thesis is the necessity, in point of health and in point of morals and mental tranquility, for the gratification of this particular passion.... The truth is, those who publish this book must have known perfectly well that an unlimited publication of this sort, put into the hands of everybody, whatever their age, whatever their condition in life, whatever their modes of life, whatever their means, put into the hands of any person who may think proper to pay sixpence for it - the thesis is this: if you do not desire to have children, and wish to gratify your sensual passions, and not undergo the responsibility of marriage; if you are desirous of doing that, I show you by a philosophical treatise, forsooth, how you may effect that object satisfactorily and safely.... It is sought to be justified upon the ground that it is only a recommendation to married people, who under the cares of their married life are unable to bear the burden of too many children. I should be prepared to argue before you that if confined to that object alone it would be most mischievous.... I deny this, and I deny that it is the purport and intention of this book. This book is sold for sixpence, and at such a price as this it will induce a circulation, which you may well conjecture, and it may be induced amongst an enormous population, there will be so many old to boys and girls and persons who may obtain it with perfect facility in the streets...

I submit to you, that from what I have read, it is an obscene book. The mode of publication is such as does not justify the book, and it is calculated to deprave and destroy the minds of those young persons especially into whose hands it may come, and therefore, it is properly the subject of an indictment.

(7) Annie Besant, statement in court (18th June, 1877)

It is not as defendant that I plead to you today - not simply as defending myself do I stand here but I speak as counsel for hundreds of the poor, and it is they for whom I defend this case. My clients are scattered up and down through the length and breadth of the land; I find them amongst the poor, amongst whom I have been so much; I find my clients amongst the fathers, who see their wage ever reducing, and prices ever rising; I find my clients amongst the mothers worn out with over-frequent child-bearing, and with two or three little ones around too young to guard themselves, while they have no time to guard them. It is enough for a woman at home to have the care, the clothing, the training of a large family of young children to look to; but it is a harder task when oftentimes the mother, who should be at home with her little ones, has to go out and work in the fields for wage to feed them when her presence is needed in the house.

I find my clients among the little children. Gentlemen, do you know the fate of so many of these children? The little ones half starved because there is food enough for two but not enough for twelve; half clothed because the mother, no matter what her skill and care, cannot clothe them with the money brought home by the breadwinner of the family; brought up in ignorance, and ignorance means pauperism and crime - gentlemen, your happier circumstances have raised you above this suffering but on you also this question presses; for these overlarge families mean also increased poor rates, which are growing heavier year by year. These poor are my clients... mothers who beg me to persist in the course on which I have entered - and at any hazard to myself, at any cost and any risk - they plead to me to save their daughters from the misery they have themselves passed through during the course of their married lives...

I will only put it to you now, that you have got before you a great social question which is becoming more and more pressing as every year goes by.... It is a fact that the object of this pamphlet, so far from destroying marriage and so far from approving any kind of illicit connection between the sexes - it is a fact that the pamphlet is written by Dr Knowlton, and circulated by us today, for the purpose which the learned judge suggested was a question of great importance, that of making early marriage possible to a very large number of young men today. Our object is not to destroy marriage but to make it more widely prevalent; not to encourage prostitution, but to destroy that which is a very prolific source of prostitution, the shrinking of young men from marriage because of the terrible responsibility that marriage often brings with it. That is the object of my co-defendant and myself...

I put it to you that there is nothing wrong in a natural desire rightly and properly gratified. There is no harm in feeling thirsty because people get drunk; there is no harm in feeling hungry because people over-eat themselves, and there is no harm in gratifying the sexual instinct if it can be gratified without injury to anyone else, and without harm to the morals of society, and with due regard to the health of those whom nature has given us the power of summoning into the world. I put it to you gravely, that it is only a false and spurious kind of modesty, which sees harm in the gratification of one of the highest instincts of human nature - an instinct which goes through all the world, not only in the animal but in the vegetable kingdom; if you are to blame Dr Knowlton because he recognises a great natural fact, then it is your duty to blame the constitution of the world, and the arrangements of nature, because you find that the reproductive instinct is attended with pleasure in its due gratification...

And I may say here, too, that Dr Knowlton remarks that "mankind will not so abstain"; as a simple matter of fact, I must put it to you that men and women, but more especially men, will not lead a celibate life, whether they are married or unmarried, and that what you have got to deal with is, that which we advocate early marriage with restraint upon the numbers of the family or else a simple mass of unlicensed prostitution, which is the ruin of both men and women when once they fall into it.

(8) Annie Besant, statement in court (19th June, 1877)

If you go to Islington you find a million of children, all under five years of age, and among them the death rate is 66.9 in a thousand, although Islington is one of the healthiest districts in the metropolis. The death rate, however, is nearly double that in the eastern districts. If you go to Whitechapel, for instance, there the death rate is as much as 102 in a thousand; they die before reaching the age of five years. In Manchester, again, the death-rate is 117 in a thousand; in Liverpool it is 132 in a thousand; and all that death rate I put down as death resulting from what I call preventable diseases, and I urge that you can only judge upon this case when you put before yourselves clearly whether it is either moral or right to allow children to be brought into the world, inoculated with the predisposition to be attacked by these preventable diseases, instead of putting, as I believe you ought to do, a check which would effectively relieve the population so terribly overcrowded; and you have to consider whether by refusing to apply such a check, we are not, by the very refusal, making a large class of criminals....

Professor Fawcett states that among "children belonging to the upper and middle classes 20 per cent die before they reach the age of five"; and he adds that the amount is more than doubled in the case of children belonging to the labouring classes. This great mortality amongst poor children is caused by neglect, by want of proper food, and by unwholesome dwellings. When we take these facts, and find that this large number of children have literally been murdered, when you consider that the number of these children who, if they had been born in a higher rank, would not have died, is calculated by Professor Fawcett as 1,150,000... you will see what a large and important question this is....

I say that men and women will marry young - in the flower of their age - and more especially will this be the case amongst the poorer classes... I cannot go to the poor man, and tell him that the brightest part of his life is to be spent alone, and that he is to be shut out for years from the comforts of a home and the happiness of married life ... Gentlemen, do not be deceived. There is no talk in this book of preventing men and women from becoming parents; all that is sought here is to limit the number of their family. And we do not aim at that because we do not love children, but, on the contrary, because we do love them, and because we wish to prevent them from coming into the world in greater numbers than there is the means of properly providing for. Children, I believe, have an influence upon parents purifying in the highest degree, because they teach the parents self-restraint, self-denial, thoughtfulness, and tenderness to an extent that cannot possibly be overestimated; and it is because I wish to have it made possible for young men and for young women to have these influences brought to bear upon them in their youth, that I advocate the circulation of a book that will put within their reach the knowledge of how to limit the extent of their families within their capabilities of providing for them; for no man can look with pride and happiness upon his home if he has more children than he can clothe and educate...

We can only suppose, for a moment, that he was utterly ignorant that the Government had done the very thing which he characterised as obscene, for I am sure all ties of party, if nothing else, would prevent a gentleman in open court from characterising the action of his colleagues in office as actions which were thoroughly obscene, and ought to be indicted at common law. I will claim that if you bring in a verdict against us it will only be fair that you should also sit in judgment upon my Lord Beaconsfield, my Lord Salisbury, and my Lord Derby, and that they should hold the same position we hold in court today, to answer for circulating books which are distinctly obscene, which we find them putting into the hands of young girls.... I hold so thoroughly that the Government is right in putting that information...in the hands of boys and girls (and I am speaking to you here as the mother of a daughter for whose education you must at least suppose I have some care and some interest), that I say to you deliberately, as mother of a daughter whom I love, that I believe it will tend to her happiness in her future, as well as to her health, that she shall not have made to her that kind of mystery about sexual functions that every man and woman must know sooner or later...

When I was first married my own doctor gave me the work of Chavasse, on the ground that it was better for a woman to read the medical details than it was for her to have to apply to one of the opposite sex to settle matters which did not need to be dealt with by the doctor; practically these pages in Knowlton's work are a very short and very careful summary of the subject dealt with by Chavasse and Bull : where you have got to deal with a sixpenny book you must summarise the details...

(9) Charles Bradlaugh, statement in court (19th June, 1877)

If you hold that the doctrine of celibacy is attended with disease and crime, and perpetuates prostitution, then you must also advocate the intelligent gratification of the reproductive functions. That restraint after marriage must be of two kinds : one, the abstinence from cohabitation which has been advocated by many doctors, who contend that during certain periods, i.e., within a certain time before and after the menstrual period, conception is either impossible, or, at any rate, difficult. Against that you have the hard fact that a well-known people, by their ceremonial laws, are prohibited from sexual intercourse during the period indicated, and notwithstanding that they are notoriously a most prolific people, so that I would submit that the restraint after marriage must mean the intelligent gratification of the functions, so that the act shall not involve bringing into life a child whom the parents are unable to support. I submit that advocacy of such a restraint has never been declared unlawful, my lord, and that it is not unlawful, and I submit that advocacy of such a restraint does not tend to deprave and corrupt the public mind, but tends to promote and to increase the morality of the people...

If you take the fact, as fact it is, that in the whole of the counties of Northumberland and Durham, while I speak, the best paid class of hewers of coal are not now averaging much more than one pound a week; take that for a man and his wife and three children only. But suppose him to have five. The Pauper Unions allow 4s 6d a week, and sometimes a little more, for boarding out a pauper child. Suppose the coalhewer has a family of five, six or seven - do the multiplication for yourselves, and leave nothing for luxury or dissipation on the part of the bread winner-I ask what means has he of purchasing the expensive treatises from which I shall quote? I now submit that it is impossible to advocate sexual restraint after marriage amongst the poor without such medical or physiological instructions as may enable them to comprehend the advocacy and utilise it. Of what use it is to take a man or woman, totally uneducated, and to tell them their duty, unless you show them how to perform it?

My contention is that the rich have certain useful information within their reach which they have no more right to have at their disposal for 1s 6d than the poor have at 6d...

I ask you, then, to consider the issues which I have put to you already and which I put to you again, viz., Is overpopulation the cause of poverty? Is over-population the cause of misery? Is over-population the cause of crime? Is over-population the cause of disease? Is it moral or immoral to check poverty, ignorance, vice, crime, and disease? I can only think you will give one answer, that it is moral to check these evils.... You may say: Try to restrain them, like Malthus, by late marriage. Aye, but even to get late marriage, you must teach poor men and women to comprehend the need for it, and, even then, if you get real celibacy, Acton and others will tell you what horrible diseases are the outcome of this state of things....

We want to prevent them bringing into the world little children to suck death, instead of life, at the breasts of their mother; and you tell us we are immoral. I should not say that, perhaps, for you, gentlemen, may judge things differently from myself; but I know the poor. I belong to them. I was barn amongst them. Among them are the earliest associations of my life. Such little ability as I possess today has come to me in the hard struggle of life. I have had no University to polish my tongue; no Alma Mater to give to me any eloquence by which to move you. I plead here simply for the class to which I belong, and for the right to tell them what may redeem their poverty and alleviate their misery. And I ask you to believe in your heart of hearts, even if you deliver a verdict against us here-I ask you, at least, to try and believe both for myself and the lady who sits beside. me (I hope it for myself, and I earnestly wish it for her), that all through we have meant to do right, even if you think we have done wrong.

(10) Alice Vickery, nurse, statement in court (20th June, 1877)