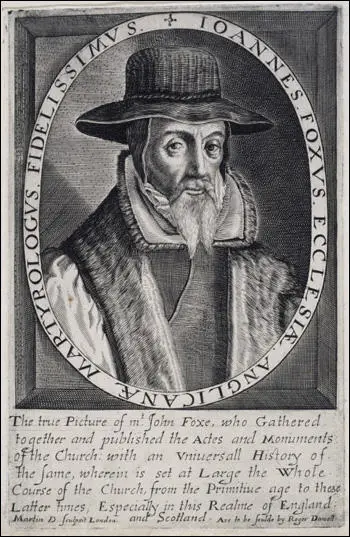

John Foxe

John Foxe was born at Boston, Lincolnshire, in about 1516. His father died when he was young and his mother subsequently married Richard Melton, a prosperous yeoman of the nearby village of Coningsby. In 1534 he entered Brasenose College. (1)

While at Oxford University he became a supporter of the ideas of Martin Luther and his opposition to the selling of pardons by Pope Leo X. As Foxe later explained: "In 1516 Pope Leo X began selling pardons, by which he gained a large amount of money from people who were eager to save the souls of their loved ones. His collectors assured the people that for every ten shillings they gave, one specified soul would be delivered from the pains of purgatory." (2)

While at university he was a witness to the burning of William Cowbridge in September 1538 for being involved in the publishing of the Bible in the English language. "The fruitful seed of the gospel at this time had taken such root in England, that now it began manifestly to spring and show itself in all places, and in all sorts of people, as it may appear in this good man Cowbridge; who, coming of a good stock and family, whose ancestors, even from Wickliff's time hitherto, had been always favourers of the gospel, and addicted to the setting forth thereof in the English tongue... At that time Dr. Smith and Dr. Cotes governed the divinity schools, who, together with other divines and doctors, seemed not in this point to show the duty which the most meek apostle requireth in divines toward such as are fallen into any error, or lack instruction or learning." (3)

John Foxe & Henry VIII

John Foxe was elected fellow of Magdalen College in July 1539 and became one of the college lecturers in logic. (4) He was strongly opposed to the idea that priests should not marry. A college statute required every fellow to take priest's orders. He was unwilling to do this. In a letter to one friend he explained that he could not remain at Magdalen "unless I castrate myself and leap into the priestly caste". To another friend he declared that "I do not intend to be circumcised this year". (5)

John Foxe became highly critical of the Church during the reign of Henry VIII. "By reading this history, a person should be able to see that the religion of Christ, meant to be spirit and truth, had been turned into nothing but outward observances, ceremonies, and idolatry. We had so many saints, so many gods, so many monasteries, so many pilgrimages. We had too many churches, too many relics (true and fake), too many untruthful miracles. Instead of worshipping the only living Lord, we worshipped dead bones; in place of immortal Christ, we worshipped mortal bread. No care was taken about how the people were led as long as the priests were fed. Instead of God's Word, man's word was obeyed; instead of Christ's testament, the pope's canon. The law of God was seldom read and never understood, so Christ's saving work and the effect on man's faith were not examined. Because of this ignorance, errors and sects crept into the church, for there was no foundation for the truth that Christ willingly died to free us from our sins - not bargaining with us but giving to us." (6)

After leaving university he stayed with Hugh Latimer, the Bishop of Worcester. Eventually Foxe secured a position as tutor in the household of Sir William Lucy, one of Latimer's friends, at Charlecote, Warwickshire. There he married Agnes Randall on 3rd February 1547. The couple moved to Stepney and over the next few years they had six children. During this period he began translating and publishing the sermons of Martin Luther. Simeon Foxe, later claimed that his father worked as a tutor to the children of Henry Howard, the Earl of Surrey. Foxe's pupils were Surrey's three eldest children, Thomas, Jane and Henry. Foxe taught them at Mountjoy House, the Duchess of Richmond's London residence.

Joan Bocher

After the execution of her friend Anne Askew on 16th July 1546, Joan Bocher, an Anabaptist, began distributing pamphlets, and expressed the opinion that Christ, the perfect God, had not been born as a man to the Virgin Mary. She was arrested and brought to trial before Bishop Nicholas Ridley and found guilty of heresy. Boucher's views upset both Catholics and Protestants. John Rogers, who had been involved in the publishing of English Bible that had been translated by William Tyndale, was brought in to persuade her to recant. After failing in his mission he declared that she should be burnt at the stake. (7)

John Foxe, who had been active in opposing the burning of heretics during the reign of Henry VIII was very distressed that Joan Bocher was now to be burned under the Protestant government of Edward VI. Although he disagreed with her views he thought that the life of "this wretched woman" should be spared and suggested that a better way of dealing with the problem was to imprison her so that she could not propagate her beliefs. Rogers insisted that she must die. Foxe replied she should not be burned: "at least let another kind of death be chosen, answering better to the mildness of the Gospel." Rogers insisted that burning alive was gentler than many other forms of death. Foxe took Rogers' hand and said: "Well, maybe the day will come when you yourself will have your hands full of the same gentle burning." (8)

It has been claimed by Christian Neff that the 12-year-old King Edward at first refused to sign the death warrant. Archbishop Thomas Cranmer insisted that "she should be punished with death for her heresy according to the law of Moses".He is said to have told Cranmer with tears, "Cranmer, I will sign the verdict at your risk and responsibility before God’s judgment throne." Cranmer was deeply impressed, and he tried once more to induce her to recant but she still refused. (9)

Joan Bocher was burnt at Smithfield on 2nd May 1550. "She died still upbraiding those attempting to convert her, and maintaining that just as in time they had come to her views on the sacrament of the altar, so they would see she had been right about the person of Christ. She also asserted that there were a thousand Anabaptists living in the diocese of London." (10)

In 1551 John Foxe published De Censura. The book called for the revival of a system of ecclesiastical discipline and for a new code of canon law. Foxe claimed that he had the support of both Archbishop Thomas Cranmer and Bishop Nicholas Ridley. Foxe also argued that adultery should not be a capital crime. This created a great deal of controversy. While Foxe had argued against imposing the death penalty on adulterers, he had also recommended that clerical sanctions, including excommunication, should be imposed on them. (11)

The Burning of Heretics

When Mary I came to the throne Foxe and his wife fled to Europe. He eventually settled in Frankfurt where he wrote about the persecution of religious reformers in the 14th century such as John Wycliffe. This material eventually appeared in his book, Foxe's Book of Martyrs (1563): "Wycliffe, seeing Christ's gospel defiled by the errors and inventions of these bishops and monks, decided to do whatever he could to remedy the situation and teach people the truth. He took great pains to publicly declare that his only intention was to relieve the church of its idolatry, especially that concerning the sacrament of communion." (12)

Foxe's friends who remained in England were soon arrested. Archbishop Thomas Cranmer was put on trial for heresy on 12th September 1555. According to Jasper Ridley, the author of Bloody Mary's Martyrs (2002): "Cranmer gave a piteous exhibition; he was utterly broken by his imprisonment, by the humiliations heaped upon him, and by the defeat of all his hopes; and the fundamental weakness in his character, his hesitations and his doubts were clearly displayed. But he steadfastly refused to recant and to acknowledge Papal Supremacy. He was condemned as a heretic." (13)

On 16th October, Cranmer was forced to watch his friends, Nicholas Ridley and Hugh Latimer, burnt at the stake for heresy. "It is reported that he fell to his knees in tears. Some of the tears may have been for himself. He had always given his allegiance to the established state; for him it represented the divine rule. Should he not now obey the monarch and the supreme head of the Church even if she wished to bring back the jurisdiction of Rome? In his conscience he denied papal supremacy. In his conscience, too, he was obliged to obey his sovereign." (14)

Cranmer was guarded by Nicholas Woodson, a devout Catholic, who attempted to persuade him to change his views. It has been claimed that this friendship came to be his only emotional support, and, to please Woodson, he began giving way to everything that he had hated. On 28th January, 1556, he signed his first hesitant submission to papal authority. This was followed by submissions on 14th, 15th and 16th February. On 24th February he was made aware that his execution would take place in a few days time. In an attempt to save his life, he signed a statement that was truly a recantation. He probably did not write it himself; the Catholic commentary on it merely says that Cranmer was ordered to sign it. (15)

Despite these recantations, Queen Mary I refused to pardon him and ordered Thomas Cranmer to be burnt at the stake. When he was told the news he probably remembered what Henry VIII said to him when he successfully persuaded the king not to execute his daughter. According to Ralph Morice Henry warned Cranmer that he would live to regret this action. (16)

On 21st March, 1556, Thomas Cranmer was brought to St Mary's Church in Oxford, where he stood on a platform as a sermon was directed against him. He was then expected to deliver a short address in which he would repeat his acceptance of the truths of the Catholic Church. Instead he proceeded to recant his recantations and deny the six statements he had previously made and described the Pope as "Christ's enemy, and Antichrist, with all his false doctrine." The officials pulled him down from the platform and dragged him towards the scaffold. (17)

Cranmer had said in the Church that he regretted the signing of the recantations and claimed that "since my hand offended, it will be punished... when I come to the fire, it first will be burned." According to John Foxe: "When he came to the place where Hugh Latimer and Ridley had been burned before him, Cranmer knelt down briefly to pray then undressed to his shirt, which hung down to his bare feet. His head, once he took off his caps, was so bare there wasn't a hair on it. His beard was long and thick, covering his face, which was so grave it moved both his friends and enemies. As the fire approached him, Cranmer put his right hand into the flames, keeping it there until everyone could see it burned before his body was touched." Cranmer was heard to cry: "this unworthy right hand!" (18)

It was claimed that just before he died Cranmer managed to throw the speech he intended to make in St Mary's Church into the crowd. A man whose initials were J.A. picked it up and made a copy of it. Although he was a Catholic, he was impressed by Cranmer's courage, and decided to keep it and it was later passed on to John Foxe, who later published it. Jasper Ridley has argued that as a propaganda exercise, Cranmer's death was a disaster for Queen Mary. "An event which has been witnessed by hundreds of people cannot be kept secret and the news quickly spread that Cranmer was repudiated his recantations before he died. The government then changed their line; they admitted that Cranmer had retracted his recantations were insincere, that he had recanted only to save his life, and that they had been justified in burning him despite his recantations. The Protestants then circulated the story of Cranmer's statement at the stake in an improved form; they spread the rumour that Cranmer had denied at the stake that he had ever signed any recantations, and that the alleged recantations had all been forged by King Philip's Spanish friars." (19)

Foxe's Book of Martyrs

In 1557 John Foxe and his growing family moved to Basel. He worked for printer Hieronymus Froben as a translator and proof reader. During this period he became friends with several continental protestant scholars. with much the greatest influence on Foxe's work was Matthias Flacius, who had written several books on early Church history. (20)

While in exile Foxe worked on his history of Christian martyrdom. In August 1559 he published Foxe's Book of Martyrs in Latin. The first section dealt was entitled "Persecution of the Early Christians". Another section looked at at the persecution of Protestants in Europe during the Middle Ages. However, most of the book covered the reigns of Henry VIII, Edward VI and Mary I. It was largely based on history books by people such as Edward Hall and John Bale.

Queen Elizabeth appeared to be a more tolerant monarch and in Foxe decided to return to England in October 1559. He travelled around the country speaking to the survivors, to the friends of the victims and the the people who had witnessed heretics being burnt at the stake. He also made copies of letters written by martyrs to family and friends, while they waited in prison for their executions. Foxe also looked at the official records of their interrogations. Foxe was very concerned with providing a factual record of the names, occupations, age, and the town or village of origin of the martyrs.

In 1563 Foxe published the first English edition of Foxe's Book of Martyrs. It included all the passages that he had already published in Latin, plus all the new material he had collected about the martyrs under Mary. The book had 1,721 pages and ran to 1,450,000 words. It was dedicated to the "most Christian and renowned princess, Queen Elizabeth". After the book was published, many people wrote to Foxe. Some pointed out minor errors in his book. Some gave him information which he had so far been unable to find. This material was included in the second edition published in 1570. This edition had 2,335 pages and 3,150,000 words. It was nearly four times the length of the Bible, and according to Jasper Ridley was the "longest single work which has ever been published in the English language." (21)

Thomas S. Freeman has pointed out that the book made good use of the library accumulated by Archbishop Matthew Parker. "Foxe's second edition also far surpassed any previous English historical work in the range of medieval chronicles and histories on which it was based. Foxe had the immense good fortune to be able to consult the vast collection of historical manuscripts gathered by Archbishop Matthew Parker. Although the primate and the martyrologist had their differences, which later became manifest, Parker saw an opportunity to use Foxe's Acts and Monuments to demonstrate his own interpretation of history in which an apostolic English church was corrupted by the papacy, in a process that began with Augustine of Canterbury's mission and became more virulent as foreign bishops like Lanfranc and Anselm were foisted on the English church after 1066. This in turn led to the establishment in the English church of such popish ‘abuses’ as transubstantiation, clerical celibacy, and auricular confession." (22)

It has been argued that the Foxe's Book of Martyrs is one of the most important books published in the English language: "The Book of Martyrs, with the full force of government propaganda behind it, undoubtedly had a powerful effect on the English people, and is one of the few books which can be said to have changed the course of history." (23)

In 1573 John Foxe edited a collection of the works of William Tyndale, Robert Barnes and John Frith. Foxe admitted that his main objective was to use logical and theological arguments, supported by historical examples, which would induce Catholics and Jews to abandon their "superstitions" and embrace the gospel. In the introduction he expressed the hope that those who "be not yet won to the word of truth, setting aside all partiality and prejudice of opinion, would with indifferent judgements, bestow some reading and hearing likewise of these three authors."

In the spring of 1575 a congregation of Anabaptist was discovered in Aldgate. They were arrested and charged with advocating that infants should not be baptized, that a Christian should neither be a magistrate or a soldier. Five recanted and another fifteen were deported. However, the group's two leaders, John Weelmaker and Henry Toorwoort were condemned to death by burning.

John Foxe took up their case and wrote to Queen Elizabeth pointing out that no burnings had taken place for seventeen years. "I have no favour for heretics, but I am a man and would spare the life of a man. To roast the living bodies of unhappy men, erring rather from blindness of judgement than from the impulse of will, in fire and flames, of which the fierceness is fed by the pitch and brimstone poured over them, in a Romish abomination... for the love of God spare their lives." Elizabeth rejected the request for mercy and they were both burnt at Smithfield. (24)

Thomas S. Freeman points out that his deep abhorrence of the death penalty should not be confused with toleration of Anabaptist beliefs. "Foxe despised the Anabaptists' doctrines and was determined to eradicate such heresies from England. He approved of the banishment of the Anabaptists and urged exile, imprisonment, flogging, or branding as alternatives to execution. Most importantly, his fundamental argument for sparing the lives of the Anabaptists was his conviction that, if they were given enough time, they could be persuaded to recant their errors. Along with Foxe's determination to eliminate false religion went a profound conviction that it should, and could, be eliminated by persuasion rather than by force." (25)

Francis Walsingham and William Cecil decided that Foxe's Book of Martyrs, could be used in the anti-Catholic propaganda campaign deployed in the 1580s against Mary, Queen of Scots and her supporters. A copy was placed in every cathedral and most churches. The English captains of the ships that sailed to the West Indies and South America to raid and plunder the Spanish towns there and to fight the Spaniards at sea, were ordered to have a copy of the book in the ship. All the English ships involved in defeating the Spanish Armada carried a copy of the book. It was argued that "their crews believed that they were fighting to save their country from a repetition of the horrors of Mary's reign if the Spaniards succeeded in invading and conquering England." (26)

John Foxe died, at his house in Grub Street, London, on 18th April 1587.

Primary Sources

(1) John Foxe, Foxe's Book of Martyrs (1563)

By reading this history, a person should be able to see that the religion of Christ, meant to be spirit and truth, had been turned into nothing but outward observances, ceremonies, and idolatry. We had so many saints, so many gods, so many monasteries, so many pilgrimages. We had too many churches, too many relics (true and fake), too many untruthful miracles. Instead of worshipping the only living Lord, we worshipped dead bones; in place of immortal Christ, we worshipped mortal bread.

No care was taken about how the people were led as long as the priests were fed. Instead of God's Word, man's word was obeyed; instead of Christ's testament, the pope's canon. The law of God was seldom read and never understood, so Christ's saving work and the effect on man's faith were not examined. Because of this ignorance, errors and sects crept into the church, for there was no foundation for the truth that Christ willingly died to free us from our sins - not bargaining with us but giving to us.

(2) Jasper Ridley, Bloody Mary's Martyrs (2002)

John Foxe, from Boston in Lincolnshire, after graduating at Magdalen College in Oxford, was ordained as a deacon in London and became an ardent Protestant. He had been horrified at the burning of Protestant heretics by Henry VIII, and was very distressed that Joan Bocher was now to be burned under the Protestant government of Edward VI. He thought that her opinions were wrong and shocking, but that the life of "this wretched woman" should be spared; she should be imprisoned in some place where she could not propagate her beliefs and where renewed efforts could be made to induce her to recant.

Foxe visited Rogers and pleaded for Joan's life; but Rogers insisted that she must die for her heresy. Foxe said that if her life must be taken away, she should not be burned: "at least let another kind of death be chosen, answering better to the mildness of the Gospel. What need to borrow from the Papal laws and bring into the Christian arena the torments of this dreadful death?" Rogers said that burning alive was gentler than many other forms of death. Foxe took Rogers' hand and said: "Well, maybe the day will come when you yourself will have your hands full of the same gentle burning."

Student Activities

Henry VIII (Answer Commentary)

Henry VII: A Wise or Wicked Ruler? (Answer Commentary)

Henry VIII: Catherine of Aragon or Anne Boleyn?

Was Henry VIII's son, Henry FitzRoy, murdered?

Hans Holbein and Henry VIII (Answer Commentary)

The Marriage of Prince Arthur and Catherine of Aragon (Answer Commentary)

Henry VIII and Anne of Cleves (Answer Commentary)

Was Queen Catherine Howard guilty of treason? (Answer Commentary)

Anne Boleyn - Religious Reformer (Answer Commentary)

Did Anne Boleyn have six fingers on her right hand? A Study in Catholic Propaganda (Answer Commentary)

Why were women hostile to Henry VIII's marriage to Anne Boleyn? (Answer Commentary)

Catherine Parr and Women's Rights (Answer Commentary)

Women, Politics and Henry VIII (Answer Commentary)

Cardinal Thomas Wolsey (Answer Commentary)

Historians and Novelists on Thomas Cromwell (Answer Commentary)

Martin Luther and Thomas Müntzer (Answer Commentary)

Martin Luther and Hitler's Anti-Semitism (Answer Commentary)

Martin Luther and the Reformation (Answer Commentary)

Mary Tudor and Heretics (Answer Commentary)

Joan Bocher - Anabaptist (Answer Commentary)

Anne Askew – Burnt at the Stake (Answer Commentary)

Elizabeth Barton and Henry VIII (Answer Commentary)

Execution of Margaret Cheyney (Answer Commentary)

Robert Aske (Answer Commentary)

Dissolution of the Monasteries (Answer Commentary)

Pilgrimage of Grace (Answer Commentary)

Poverty in Tudor England (Answer Commentary)

Why did Queen Elizabeth not get married? (Answer Commentary)

Francis Walsingham - Codes & Codebreaking (Answer Commentary)

Codes and Codebreaking (Answer Commentary)

Sir Thomas More: Saint or Sinner? (Answer Commentary)

Hans Holbein's Art and Religious Propaganda (Answer Commentary)

1517 May Day Riots: How do historians know what happened? (Answer Commentary)