Nicholas Ridley

Nicholas Ridley, the son of Christopher and Anne Ridley was born near Willimoteswick in about 1502. He attended school in Newcastle upon Tyne before studying at Pembroke College "where he soon became well known for his intelligence". (1)

While at Cambridge University Ridley was a regular visitor to the White Horse tavern that had been nicknamed "Little Germany" as the Lutheran creed was discussed within its walls, and the participants were known as "Germans". Those involved in the debates about religious reform included Thomas Cranmer, William Tyndale, Hugh Latimer, Nicholas Shaxton and Matthew Parker. Ridley also went to hear the sermons of preachers such as Robert Barnes and Thomas Bilney. (2)

Ridley's biographer, Susan Wabuda, has argued that "he received from the university every promotion that could be bestowed: including all of his degrees; a fellowship at Pembroke from 1524; a chaplaincy to the university in 1531... With his many talents and superb connections, from the late 1530s Ridley began to receive ever more exalted attention from outside the university. In 1537 Archbishop Cranmer called him from Cambridge to be one of his chaplains." (3)

Nicholas Ridley - Religious Reformer

Nicholas Ridley became the vicar of Herne in Kent and a canon of Canterbury Cathedral. It has been claimed by Jasper Ridley that Ridley came under the influence of the religious ideas promoted by Ulrich Zwingli. He later persuaded Archbishop Cranmer "to renounce the Real Presence and to adopt the Zwinglian doctrine of a Spiritual Presence, which had been formulated by Ulrich Zwingli". (4)

Susan Wabuda has pointed out that a s with Thomas Cranmer and Hugh Latimer, Ridley's re-evaluation of Christian doctrine proceeded gradually. Initially the reformers "strove to disseminate the word of God through sermons and the printing press with the aim of bringing about a deep spiritual renewal throughout society". Much of the "received wisdom of the Catholic church (including the sacraments) had to be re-examined, and where necessary cast aside." (5)

The main issue discussed by the reformers concerned the doctrine of transubstantiation, whereby the bread and wine became in actual fact the body and blood of Christ. The Catholic Church believed because it is impossible, it is proof of the overwhelming power of God. Martin Luther believed in the real presence of Christ in the sacrament, but denied that he was there "in substance". Luther believed in what became known as consubstantiation or sacramental union, whereby the integrity of the bread and wine remain even while being transformed by the body and blood of Christ. Eventually, Ridley, accepted the interpretation of Luther. (6)

Another important issue involved the production of the Bible in the English language. Henry VIII agreed with the leaders of the Catholic Church, that copies should be available only in Latin. One of Ridley's friends from university, William Tyndale, began work on an English translation of the New Testament. This was a very dangerous activity for ever since 1408 to translate anything from the Bible into English was a capital offence. (7) In 1523 he travelled to London for a meeting with Cuthbert Tunstall, the Bishop of London. Tunstall refused to support Tyndale in this venture but did not organize his persecution. Tyndale later wrote that he now realized that "to translate the New Testament… there was no place in all England" and left for Germany in April 1524.

Tyndale argued: "All the prophets wrote in the mother tongue... Why then might they (the scriptures) not be written in the mother tongue... They say, the scripture is so hard, that thou could never understand it... They will say it cannot be translated into our tongue... they are false liars." In Cologne he translated the New Testament into English and it was printed by Protestant supporters in Worms in 1526. (8) Other reformers from England such as John Rogers and Miles Coverdale, moved to Germany to help Tyndale with his work. Ridley privately agreed with this venture but were unwilling to argue with the King over this issue.

After the reformer's main enemy, Sir Thomas More, was executed on 6th July, 1535. Archbishop Thomas Cranmer and Thomas Cromwell, were now the key political figures in England. They wanted the Bible to be available in English. This was a controversial issue as William Tyndale had been denounced as a heretic and had been burnt at the stake on 6th October, 1536. The edition they promoted, although mainly the work of Tyndale, had the name of Miles Coverdale on the cover. Cranmer approved the Coverdale version on 4th August 1538, and asked Cromwell to present it to the king in the hope of securing royal authority for it to be available in England. (9)

If you find this article useful, please feel free to share on websites like Reddit. You can follow John Simkin on Twitter, Google+ & Facebook or subscribe to our monthly newsletter.

Henry agreed to the proposal on 30th September, 1538. Every parish had to purchase and display a copy of the Coverdale Bible in the nave of their church for everybody who was literate to read it. "The clergy was expressly forbidden to inhibit access to these scriptures, and were enjoined to encourage all those who could do so to study them." (10) Cranmer was delighted and wrote to Cromwell praising his efforts and claiming that "besides God's reward, you shall obtain perpetual memory for the same within the realm." (11)

The Six Articles

In May 1539 the bill of the Six Articles was presented by Thomas Howard, the Duke of Norfolk in Parliament. It was soon clear that it had the support of Henry VIII. Although the word "transubstantiation" was not used, the real presence of Christ's very body and blood in the bread and wine was endorsed. So also was the idea of purgatory. The six articles presented a serious problem for Ridley and other religious reformers. Ridley had argued against transubstantiation and purgatory for many years. Ridley now faced a choice between obeying the king as supreme head of the church and standing by the doctrine he had had a key role in developing and promoting for the past decade. (12)

Bishop Hugh Latimer and Bishop Nicholas Shaxton both spoke against the Six Articles in the House of Lords. Thomas Cromwell was unable to come to their aid and in July they were both forced to resign their bishoprics. For a time it was thought that Henry would order their execution as heretics. He eventually decided against this measure and instead they were ordered to retire from preaching. Nicholas Ridley shared his friend's views but kept his thoughts to himself. Robert Barnes, who opposed the Six Articles, was burnt at the stake on 30th July, 1540. (13)

Reign of Edward VI

Henry VIII died on 28th January 1547. Edward VI was only nine years old and was too young to rule. In his will, Henry had nominated a Council of Regency, made up of 16 nobles and churchman to assist his son in governing his new realm. It was not long before his uncle, Edward Seymour, Duke of Somerset, emerged as the leading figure in the government and was given the title Lord Protector. He was sympathetic to the religious ideas of people like Ridley and he ordered the release from prison of reformers such as Bishop Hugh Latimer. (14)

This gave the opportunity for Nicholas Ridley and his friends such as Archbishop Thomas Cranmer their long-awaited opportunity to implement the doctrinal changes they had desired. Later that year the Six Articles were repealed. On 4th September 1547 Ridley was elected Bishop of Rochester. Among his first public pronouncements as bishop was a sermon at Paul's Cross on the sacrament of the altar (now under reassessment in parliament), which attempted to find a careful balance that would distance the English church from the radical opinions of the Anabaptists. (15)

Edmund Bonner, a former persecutor of the heretics, lost his post as Bishop of London. He was now replaced in the post by Nicholas Ridley in February 1550. (16) Among his earliest acts was to order the destruction of altars, to "turn the simple from the old superstitious opinions of the popish mass", and their replacement with "honest" tables that would help to instill "the right use of the Lord's supper" as a godly meal. By the end of the year every church in the city but one had a communion table. He examined every incumbent and curate for his learning, and threatened to "eject" those who failed to come up to the standards he required. (17)

Lady Jane Grey

In April 1552 Edward VI fell ill with a disease that was diagnosed first as smallpox and later as measles. He made a surprising recovery and wrote to his sister, Elizabeth, that he had never felt better. However, in December he developed a cough. Elizabeth asked to see her brother but John Dudley, the lord protector, said it was too dangerous. In February 1553, his doctors believed he was suffering from tuberculosis. In March the Venetian envoy saw him and said that although still quite handsome, Edward was clearly dying. (18)

In order to secure his hold on power, Dudley devised a plan where Jane would marry his son, Guildford Dudley. According to Philippa Jones, the author Elizabeth: Virgin Queen (2010): "Early in 1553, Dudley... began working to persuade the King to change the succession. Edward VI was reminded that Mary and Elizabeth were both illegitimate, and more importantly, that Mary would bring Catholicism back to England. Dudley reasoned that if Mary were to be struck out of the succession, how could Elizabeth, her equal, be left in? Furthermore, he argued that both the princesses would seek foreign husbands, jeopardizing English sovereignty." (19)

Under the influence of the Lord Protector, Edward made plans for the succession. Sir Edward Montague, chief justice of the common pleas, testified that "the king by his own mouth said" that he was prepared to alter the succession because the marriage of either Princess Mary or Princess Elizabeth to a foreigner might undermine both "the laws of this realm" and "his proceedings in religion". According to Montague, Edward also thought his sisters bore the "shame" of illegitimacy. (20)

At first Jane refused to marry Guildford on the grounds that she had already been promised to Edward Seymour, the Earl of Hertford, the son of Edward Seymour, the Duke of Somerset. However, her protests were overcome "by the urgency of her mother and the violence of her father, who compelled her to accede to his commands by blows". (21) The marriage took place on 21st May 1553 at Durham House, the Dudleys' London residence, and afterwards Jane went back to her parents. She was told Edward was dying and she must hold herself in readiness for a summons at any moment. "According to her own account, Jane did not take this seriously. Nevertheless she was obliged to return to Durham House. After a few days she fell sick and, convinced that she was being poisoned, begged leave to go out to the royal manor at Chelsea to recuperate." (22)

King Edward VI died on 6th July, 1553. Three days later one of Northumberland's daughters came to take her to Syon House, where she was ceremoniously informed that the king had indeed nominated her to succeed him. Jane was apparently "stupefied and troubled" by the news, falling to the ground weeping and declaring her "insufficiency", but at the same time praying that if what was given to her was "‘rightfully and lawfully hers", God would grant her grace to govern the realm to his glory and service. (23)

On 10th July, Queen Jane arrived in London. An Italian spectator, witnessing her arrival, commented: "She is very short and thin, but prettily shaped and graceful. She has small features and a well-made nose, the mouth flexible and the lips red. The eyebrows are arched and darker than her hair, which is nearly red. Her eyes are sparkling and reddish brown in colour." (24) Guildford Dudley, "a tall strong boy with light hair’, walked beside her, but Jane apparently refused to make him king, saying that "the crown was not a plaything for boys and girls." (25)

Bishop Nicholas Ridley went along with Dudley's plan. (26) Jane was proclaimed queen at the Cross in Cheapside, a letter announcing her accession was circulated to the lords lieutenant of the counties, and Ridley preached a sermon in her favour at Paul's Cross, denouncing both Mary and Elizabeth as bastards, but Mary especially as a papist who would bring foreigners into the country. It was only at this point that Jane realised that she was "deceived by the Duke of Northumberland and the council and ill-treated by my husband and his mother". (27)

Queen Mary, who had been warned of what John Dudley, the Duke of Northumberland, had done and instead of going to London as requested, she fled to Kenninghall in Norfolk. As Ann Weikel has pointed out: "Both the earl of Bath and Huddleston joined Mary while others rallied the conservative gentry of Norfolk and Suffolk. Men like Sir Henry Bedingfield arrived with troops or money as soon as they heard the news, and as she moved to the more secure fortress at Framlingham, Suffolk, local magnates like Sir Thomas Cornwallis, who had hesitated at first, also joined her forces." (28)

Mary summoned the nobility and gentry to support her claim to the throne. Richard Rex argues that this development had consequences for her sister, Elizabeth: "Once it was clear which way the wind was blowing, she (Elizabeth) gave every indication of endorsing her sister's claim to the throne. Self-interest dictated her policy, for Mary's claim rested on the same basis as her own, the Act of Succession of 1544. It is unlikely that Elizabeth could have outmanoeuvred Northumberland if Mary had failed to overcome him. It was her good fortune that Mary, in vindicating her own claim to the throne, also safeguarded Elizabeth's." (29)

The problem for Dudley was that the vast majority of the English people still saw themselves as "Catholic in religious feeling; and a very great majority were certainly unwilling to see - King Henry's eldest daughter lose her birthright." (30) When most of Dudley's troops deserted he surrendered at Cambridge on 23rd July, along with his sons and a few friends, and was imprisoned in the Tower of London two days later. Tried for high treason on 18th August he claimed to have done nothing save by the king's command and the privy council's consent. Mary had him executed at Tower Hill on 22nd August. In his final speech he warned the crowd to remain loyal to the Catholic Church. (31)

Arrest and Execution of Nicholas Ridley

Queen Mary now ordered the arrests of the leading Protestants in England. This included Nicholas Ridley. He was taken to the Tower of London. So many Protestants were arrested that Latimer had to share his apartment with Thomas Cranmer, Hugh Latimer and John Bradford. (32) To their mutual comfort, they "did read over the new testament with great deliberation and painful study", discussing again the meaning of Christ's sacrifice, and reinforcing their opinions on the spiritual presence in the Lord's supper. (33)

In March the three former bishops were moved to the Bocardo Prison in Oxford. Ridley, Latimer and Cranmer refused to recant and spent the succeeding months waiting for the inevitable. In early 1555 Lord Chancellor Stephen Gardiner began prepare a formal set-piece trial that would discredit the entire reform movement from the 1520s onwards. While in prison Ridley wrote a Brief Declaration of the Lord's Supper, written in simple, accessible language for the widest possible readership. Latimer's servant, Augustine Bernher, smuggled it out of prison and it was published in Europe. (34)

Nicholas Ridley and Hugh Latimer were tried at the end of September 1555, Latimer complained that he had been kept "so long to the school of oblivion" with only "bare walls" for a library, that he could not defend himself adequately. (45) Unrepentant he unleashed upon his audience a categorical attack against the Catholic Church, which he characterized as "the traditional enemy of the true, persecuted flock of Christ". (35)

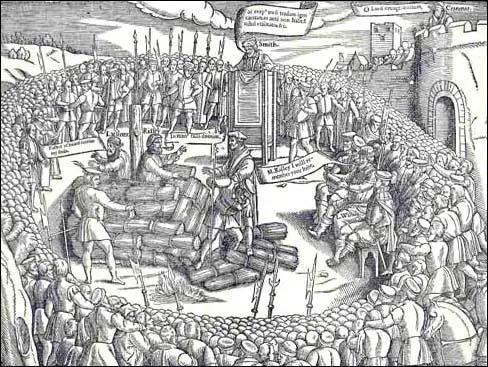

Ridley and Latimer were sentenced to be burnt at the stake for heresy on 16th October, 1555. John Foxe recalled that Ridley's brother gave him some gunpowder to hang around his neck. Latimer shouted to Ridley: "Be of good comfort Master Ridley, and play the man: we shall this day light such a candle by God's grace in England, as I trust shall never be put out". Foxe claimed that after Latimer "stroked his face with his hands, and as it were bathed them a little in the fire, he soon died with very little pain."

Nicholas Ridley took some time to die: "Ridley, by reason of the evil making of the fire unto him... burned clean all his nether parts before it touched the upper... Yet in all this torment he forgot not to call upon God... Let the fire come to me, I cannot burn. In which pains he laboured, till one of the standers by with his bill, pulled the faggots above, and when he saw the fire flame up, he wrested himself into that side. And when the flame touched the gunpowder, he was seen to stir no more." (36)

Primary Sources

(1) Jasper Ridley, Bloody Mary's Martyrs (2002)

In London and south-east England the people rose everywhere for Mary. When Nicholas Ridley preached a sermon at Paul's Cross - the pulpit in the courtyard of St Paul's Cathedral in London where government spokesman preached - and said that Mary and Elizabeth were bastards and the Queen Jane was their lawful sovereign, he was shouted down by the people.

(2) John Foxe, Book of Martyrs (1563)

Ridley, by reason of the evil making of the fire unto him... burned clean all his nether parts before it touched the upper... Yet in all this torment he forgot not to call upon God... Let the fire come to me, I cannot burn. In which pains he laboured, till one of the standers by with his bill, pulled the faggots above, and when he saw the fire flame up, he wrested himself into that side. And when the flame touched the gunpowder, he was seen to stir no more.

Student Activities

Henry VIII (Answer Commentary)

Henry VII: A Wise or Wicked Ruler? (Answer Commentary)

Henry VIII: Catherine of Aragon or Anne Boleyn?

Was Henry VIII's son, Henry FitzRoy, murdered?

Hans Holbein and Henry VIII (Answer Commentary)

The Marriage of Prince Arthur and Catherine of Aragon (Answer Commentary)

Henry VIII and Anne of Cleves (Answer Commentary)

Was Queen Catherine Howard guilty of treason? (Answer Commentary)

Anne Boleyn - Religious Reformer (Answer Commentary)

Did Anne Boleyn have six fingers on her right hand? A Study in Catholic Propaganda (Answer Commentary)

Why were women hostile to Henry VIII's marriage to Anne Boleyn? (Answer Commentary)

Catherine Parr and Women's Rights (Answer Commentary)

Women, Politics and Henry VIII (Answer Commentary)

Cardinal Thomas Wolsey (Answer Commentary)

Historians and Novelists on Thomas Cromwell (Answer Commentary)

Martin Luther and Thomas Müntzer (Answer Commentary)

Martin Luther and Hitler's Anti-Semitism (Answer Commentary)

Martin Luther and the Reformation (Answer Commentary)

Mary Tudor and Heretics (Answer Commentary)

Joan Bocher - Anabaptist (Answer Commentary)

Anne Askew – Burnt at the Stake (Answer Commentary)

Elizabeth Barton and Henry VIII (Answer Commentary)

Execution of Margaret Cheyney (Answer Commentary)

Robert Aske (Answer Commentary)

Dissolution of the Monasteries (Answer Commentary)

Pilgrimage of Grace (Answer Commentary)

Poverty in Tudor England (Answer Commentary)

Why did Queen Elizabeth not get married? (Answer Commentary)

Francis Walsingham - Codes & Codebreaking (Answer Commentary)

Codes and Codebreaking (Answer Commentary)

Sir Thomas More: Saint or Sinner? (Answer Commentary)

Hans Holbein's Art and Religious Propaganda (Answer Commentary)

1517 May Day Riots: How do historians know what happened? (Answer Commentary)