Benjamin V. Cohen

Cohen served as counsel for the American Zionist Movement and attended the 1919 Paris Peace Conference and helped to negotiate the League of Nations mandate for Palestine. A young student, Ella Winter, also worked with Frankfurter: "Ben Cohen, a tall, slender, trembling young American whose clothes hung insecurely on a diffident frame. His fingers were long and skinny, and his hands didn't know what to do. He had a long nose, straight brown hair brushed slantwise from a broad white forehead above rimless glasses, and a shaking frightened voice."

Cohen worked for Louis Brandeis as a law clerk before practicing law in New York City. In 1933 Felix Frankfurter, who was providing legal advice to President Franklin D. Roosevelt, suggested that three of his former students, Cohen, Thomas Corcoran and James M. Landis, could help draft legislation. William E. Leuchtenburg, the author of Franklin D. Roosevelt and the New Deal (1963), has pointed out: "Roosevelt had discovered Corcoran and Cohen, who had teamed up to draft Wall Street regulatory legislation, to be remarkably resourceful in resolving knotty governmental problems, and by the spring of 1935 "the boys," as Frankfurter called them, were playing key roles in the New Deal."

Cohen and Corcoran helped draft the Federal Securities Act (1933), the Tennessee Valley Authority (1933), Securities Exchange Act (1934), the Federal Housing Administration (1934), Securities Exchange Commission (1935), the Public Utilities Holding Company Act (1935), Rural Electrification Administration Act (1935) and the Fair Employment Act (1938)

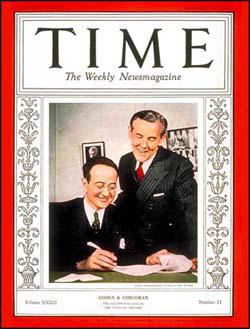

Cohen and Corcoran lived with Cohen and five other New Dealers in a house on R Street in Georgetown and were known as "the scarlet-fever boys from the little red house in Georgetown." Cohen and Corcoran were known as the "Gold Dust Twins" and appeared on the cover of Time Magazine on 12th September, 1938. One friend described Cohen as "like a Dickens portrait of an absent-minded professor."

In 1940 Cohen helped write the Lend-Lease plan. The following year he became counsel for John Gilbert Winant, American Ambassador to London. He also served as general counsel for the Office of Economic Stabilization. Cohen also assisted in the drafting of the 1944 Dumbarton Oaks agreements leading to the establishment of the United Nations.

In 1945 Cohen served as the United States' chief draftsman at the Potsdam Conference. Charles L. Mee, the author of Meeting at Potsdam (1975): "Cohen was known for his slouching posture, sloppy dress, absentminded table manners - and for a skill at drafting legislation that was generally reckoned the best in the United States." Cohen also drafted a 1957 Civil Rights Act and was special assistant to President John F. Kennedy on disarmament issues.

Benjamin Victor Cohen died from complications due to pneumonia in Washington, D.C. on 15th August, 1983.

Primary Sources

(1) William E. Leuchtenburg, Franklin D. Roosevelt and the New Deal (1963)

The shy, modest Cohen, a Jew from Muncie, Indiana, was a former Brandeis law clerk who had developed into a brilliant legislative draftsman. Corcoran, an Irishman from a Rhode Island mill town, had gone from Harvard Law School to Washington in 1926 to serve as secretary to Mr. Justice Holmes; Holmes found him "quite noisy, quite satisfactory, and quite noisy." Roosevelt had discovered Corcoran and Cohen, who had teamed up to draft Wall Street regulatory legislation, to be remarkably resourceful in resolving knotty governmental problems, and by the spring of 1935 "the boys," as Frankfurter called them, were playing key roles in the New Deal.

Corcoran was a new political type: the expert who not only drafted legislation but maneuvered it through the treacherous corridors of Capitol Hill. Two Washington reporters wrote of him: "He could play the accordion, sing any song you cared to mention, read Aeschylus in the original, quote Dante and Montaigne by the yard, tell an excellent story, write a great bill like the Securities Exchange Act, prepare a presidential speech, tread the labyrinthine maze of palace politics or chart the future course of a democracy with equal ease." He lived with Cohen and five other New Dealers in a house on R Street; as early as the spring of 1934, G.O.P. congressmen were learning to ignore the sponsors of New Deal legislation and level their attacks at "the scarlet-fever boys from the little red house in Georgetown."

In the first two years of the New Deal, the Brandeisians chafed as the NRA advocates sat at the President's right hand. They rejoiced only in the TVA, since it both checked monopoly and accentuated decentralization, and in the regulation of securities issues and the stock market, which marked the success of Brandeis' earlier crusade against the money power. Not until 1935 did the Brandeisians make their way. That year saw the triumph of the decentralizers in the fight over the social security bill, and the enhanced power in TVA of Frankfurter's follower, David Lilienthal. Brandeis himself had a direct hand

in the most important victory of all: the invalidation of the NRA.© John Simkin, March 2013