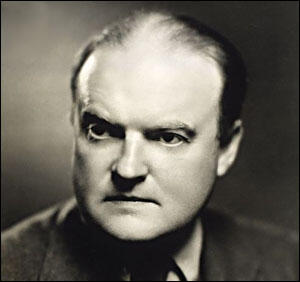

Edmund Wilson

Edmund Wilson, the son of a railroad lawyer, was born in Red Bank, New Jersey on 8th May, 1895. After attending Princeton University (1912-1916), Wilson was briefly a reporter for the New York Sun.

Wilson served in the United States Army during the First World War. After working in an army hospital he was transferred to the Intelligence Unit at General Headquarters in Chaumont.

After the war Wilson became managing editor of Vanity Fair. Later he became associate editor of the The New Republic (1926-1931) and a book reviewer for the New Yorker. Deeply influenced by the ideas of Karl Marx, Wilson argued for a socially responsible fiction and helped to influence the work of novelists such as Upton Sinclair, John Dos Passos, Sinclair Lewis, Floyd Dell and Theodore Dreiser.

Throughout his life Wilson wrote plays, novels and poems. However, his most important writing was literary criticism. This included Axel's Castle (1931), Travels in Two Democracies (1936), The Triple Thinkers (1938), To the Finland Station (1940), The Wound and the Bow (1940),The Boys in the Back Room (1941), Classics and Commercials (1950) and The Shores of Light (1952).

The New Yorker wrote: "For a writer, the rarest privilege is not merely to describe his country and time but to help shape them. Wilson was among the fortunate handful of writers who have succeeded in doing this, with books that are like bold deeds and that will live a long time after him, keeping him with us against our need."

Edmund Wilson, who published two autobiographies, A Piece of My Mind (1956) and Landscapes, Characters and Conversations (1967), died in New York on 12th June, 1972.

Primary Sources

(1) Edmund Wilson, The Army: 1917-1919 (1967)

I remember a curious patient who came to the hospital in France. He had a small undeveloped head left naked by close cropping, and his screwed-up features were as fixed as a face carved out of peach-stone. One felt that he was densely immured in some impregnable stronghold of stupidity or dazed by some great transplantation. He seemed the last of human creatures, something far less responsive than a dog. When he spoke, it was in some barbarous and scarcely intelligible dialect; one was always surprised to find that he could answer questions at all. It appeared, when the doctors cross-examined him, that he had bayoneted a young German and had not been able to forget it.

(2) Edmund Wilson, The Army: 1917-1919 (1967)

Before I had left Vittel, the flu epidemic of 1918 had taken, I think, as heavy a toll of our troops as any battle with the Germans had done. The hospitals were crowded with flu patients, many of whom died. I was in night duty and on my feet most of the time.

The other night orderly was an elderly undertaker, who went around in felt slippers, with a lantern and a kind of nightcap on his head. He knew just how to handle dead bodies. We would put them on a stretcher and carry them down to a basement room, where we sometimes had to pile them up like dogs. They were buried in big common ditches.

This was much the busiest time in our hospitals. We never had a chance to think - though doctors and nurses also died - about catching the disease ourselves. When the worst of it was over, I did collapse, although I had not caught the flu.

(3) Edmund Wilson visited Chicago and the Hull House Settlement in 1932.

Chicago is one of the darkest of great cities. In the morning, the winter sun does not seem to give any light: it leaves the streets dull. It is more like a forge which has just been started up, with its fires just burning red, an an atmosphere darkened by coal-fumes. All the world seems made of gray fog - gray fog and white smoke - the great square white-and-gray buildings seem to have been pressed out of the saturated atmosphere. The smooth asphalt of the lake-side road seems solidified polished smoke. The lake itself, in the dawn, is of a strange stagnant substance like pearl that is becoming faintly liquid and luminous.

The Chicago River, dull green, itself a work of engineering, runs backward along its original course, buckled with black iron bridges, which unclose, one after the other, each in two short fragments, as a tug drags car-barges under them, like the peristaltic movement of the stomach pushing a tough piece of food along. The sun for a time half-reveals these scenes, but its energies are only brief. The afternoon has scarcely established itself as an identifiable phenomenon when light succumbs to dullness, and the day lapses back into dark. The buildings seem mounds of soft darkness caked and carved out of swamp-mud and rubber-stamped here and there with neon signs.

(4) In his book, The American Earthquake Edmund Wilson wrote about the social reformer, Jane Addams (1958)

A little girl with curvature of the spine, whose mother had died when she was a baby, she abjectly admired her father, a man of consequence in frontier Illinois, a friend of Lincoln and a member of the state legislature, who had a floor mill and a lumber mill on his place. Whenever there were strangers at Sunday school, she would try to walk out with her uncle so that her father should not be disgraced by people's knowing that such a fine man had a daughter with a crooked spine.

When he took her one day to a mill which was surrounded by horrid little houses and explained to her, in answer to her questions, that the reason people lived in such houses was that they couldn't afford anything better, she told her father that, when she grew up, she should herself continue to live in a big house but it should stand among the houses of poor people.

(5) New Yorker, Edmund Wilson's obituary (24th June, 1972)

For a writer, the rarest privilege is not merely to describe his country and time but to help shape them. Wilson was among the fortunate handful of writers who have succeeded in doing this, with books that are like bold deeds and that will live a long time after him, keeping him with us against our need.