International Workingmen's Association (First International)

Karl Marx received several letters urging him to establish an international socialist movement after the failure of the 1848 revolutions in Europe. He replied to one letter that "since 1852 I had not been associated with any association and was firmly convinced that my theoretical studies were of greater use to the working class than my meddling with associations which had now had their day on the Continent." In another letter he told Ferdinand Freiligrath that "whereas you are a poet, I am a critic and for me the experiences of 1849-1852 were quite enough." (1)

Marx's friend, George Julian Harney, was a great believer in internationalism. "People are beginning to understand that foreign as well as domestic questionsdo affect them... that the success of Republicanism in France would be the doom of Tyranny in every other land; and the triumph of England's democratic Charter would be the salvation of the millions throughout Europe." (2)

Britain experienced an economic boom in the late 1840s and early 1850s and there was a decline in the activity of working-class organizations such as the Chartists. This changed with the economic crisis that started in 1857. Over the next two years there were strikes for higher wages and shorter hours. In 1859 attempts were made to join forces with workers in France. (3)

The historian Eric Hobsbawm pointed out that the reasons for this new trend was "a curious amalgam of political and industrial action, of various kinds of radicalism from the democratic to the anarchist, of class struggles, class alliances and government or capitalist concessions... but above all it was international, not merely because, like the revival of liberalism, it occured simultaneously in various countries, but because it was inseparable from the international solidarity of the working classes." (4)

A group of trade unionists that became known collectively as the "junta" urged the establishment of an international organisation. This included Robert Applegarth, William Allan, George Odger, Johann Eccarius and Benjamin Lucraft. "The aim of the Junta was to satisfy the new demands which were being voiced by the workers as an outcome of the economic crisis and the strike movement. They hoped to broaden the narrow outlook of British trade unionism, and to induce the unions to participate in the political struggle". (5)

International Workingmen's Association

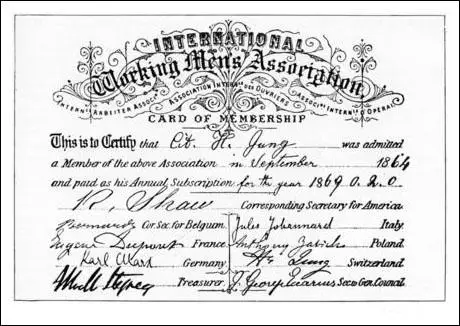

On September 28, 1864, an international meeting for the reception of the French delegates took place in St. Martin’s Hall in London. The meeting was organised by George Howell and the historian Edward Spencer Beesly was in the chair and he advocated "a union of the workers of the world for the realisation of justice on earth". (6)

In his speech, Beesly "pilloried the violent proceedings of the governments and referred to their flagrant breaches of international law. As an internationalist he showed the same energy in denouncing the crimes of all the governments, Russian, French, and British, alike. He summoned the workers to the struggle against the prejudices of patriotism, and advocated a union of the toilers of all lands for the realisation of justice on earth." (7)

The meeting was a great success. "The big hall was filled to the point of suffocation. Speeches were made by Frenchmen, Englishmen, Italians and Irish." Politically... those who attended included "old Chartists and Owenites, Blanquists and followers of Proudhon, Polish democrats and adherents of Mazzini... Its social composition, however, was far more uniform. Workers formed the preponderating majority." (7a)

The new organisation was called the International Workingmen's Association (IWMA). Karl Marx attended the meeting and he was asked to become a member of the General Council that consisted of two Germans, two Italians, three Frenchmen and twenty-seven Englishmen (eleven of them from the building trade). Marx was proposed as President but as he later explained: "I declared that under no circumstances could I accept such a thing, and proposed Odger in my turn, who was then in fact re-elected, although some people voted for me despite my declaration." (8)

The General Council met for the first time on 5th October. George Odger was elected as President and William Cremer as Secretary. After "a very long and animated discussion" the Council could not agree on a programme. Johann Eccarius privately told Marx: "You absolutely must impress the stamp of your terse yet pregnant style upon the first-born child of the European workmen's organisation". (9) Marx told Friedrich Engels "the whole leadership is in our hands". (9a)

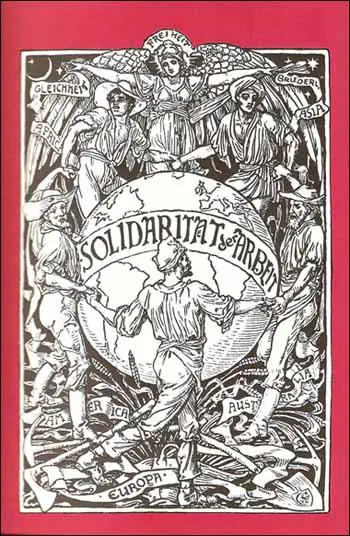

Karl Marx agreed to outline the purpose of the organization. The General Rules of the International Workingmen's Association was published in October 1864. Marx's introduction pointed out what they hoped to achieve: "That the emancipation of the working classes must be conquered by the working classes themselves, that the struggle for the emancipation of the working classes means not a struggle for class privileges and monopolies, but for equal rights and duties, and the abolition of all class rule... That the emancipation of labor is neither a local nor a national, but a social problem, embracing all countries in which modern society exists, and depending for its solution on the concurrence, practical and theoretical, of the most advanced countries." (10)

Friedrich Engels also joined the General Council but refused to to accept the office of treasurer: "Citizen Engels objected that none but working men ought to be appointed to have anything to do with the finances". Marx was asked to draw up the fundamental documents of the new organisation. He admitted that "It was very difficult to manage things in such a way that our views could secure expression in a form acceptable to the Labour movement in its present mood. A few weeks hence these British Labour leaders will he hobnobbing with Bright and Cobden at meetings to demand an extension of the franchise. It will take time before the reawakened movement will allow us to speak with the old boldness." (11)

Over the next few months other European radicals such as Wilhelm Liebknecht, August Bebel, Élisée Reclus, Ferdinand Lassalle, William Greene, Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, Friedrich Sorge and Louis Auguste Blanqui joined the organisation. Mikhail Bakunin was aware of the growth of the International Workingmen's Association and after forming the International Alliance of Socialist Democracy, he proposed a merger between the two organisations on equal terms, where he would effectively become co-president of the IWMA. This idea was rejected but in 1868 it was agreed to allow the Alliance of Socialist Democracy to become an ordinary affiliate organisation. (12)

The IWMA gave its support to strikes taking place in Europe. The financial help given by British trade unions to the striking Paris bronze workers led to their victory. The IWMA was also involved in helping Geneva builders and Basle silk-weavers. Wilhelm Liebknecht and August Bebel were gradually building up support for the organisation in Germany. David McLellan points out that the IWA was "steadily gaining in size, success and prestige". (13)

Karl Marx pointed out that: "The International was founded in order to replace the socialist and semi-socialist sects with a genuine organisation of the working class for its struggle... Socialist sectarianism and a real working-class movement are in inverse ratio to each other. Sects have a right to exist only so long as the working class is not mature enough to have an independent movement of its own: as soon as that moment arrives sectarianism becomes reactionary... The history of the International is a ceaseless battle of the General Council against dilettantist experiments and sects." (14)

Karl Marx had come into conflict with Pierre-Joseph Proudhon and his supporters who he accused of "dreaming of utopia but had a dislike of trade unions. Marx told Engels: "I will personally make hay out of the asses of Proudhonists at the next Congress. I have managed the whole thing diplomatically and did not want to come out personally until my book was published and our society had struck roots." (15)

His main rival in the IWMA was Mikhail Bakunin who he thought was trying to take control of the organisation. "Towards the end of 1868 the International within the International, and to place himself at his head. For M. Bakunin, his doctrine (an absurd patchwork composed of bits and pieces of views taken from Proudhon, Saint-Simon, etc.) was, and still is, something of secondary importance, serving him only as a means of acquiring personal influence and power. But if Bakunin, as a theorist, is nothing, Bakunin, the intriguer, has attained to the highest peak of his profession." (16)

The Paris Commune

The outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War took place on 16th July 1870. It was an attempt by Napoleon III to preserve the Second French Empire against the threat posed by German states of the North German Confederation led by the Prussian chancellor Otto von Bismarck. The International Workingmen's Association had declared at its conference the previous year that if war broke out a general strike should take place. However, Marx had privately argued that this would end in failure as the "working-class... is not yet sufficiently organised to throw any decisive weight on to the scales". (17)

The Paris section of the IWMA immediately denounced the war. However, in Germany opinion was divided but the majority of socialists considered the war to be a defensive one and in the Reichstag only Wilhelm Liebknecht and August Bebel refused to vote for war credits and spoke vigorously against the annexation of Alsace-Lorraine. For this they were charged with treason and imprisoned. (18)

Marx believed that a German victory would help his long-term desire for a socialist revolution. He pointed out to Engels that German workers were better organised and better disciplined than French workers who were greatly influenced by the ideas of Pierre-Joseph Proudhon: "The French need a drubbing. If the Prussians are victorious then the centralisation of the State power will give help to the centralisation of the working class... The superiority of the Germans over the French in the world arena would mean at the same time the superiority of our theory over Proudhon's and so on." (19)

A few days later Karl Marx issued a statement on behalf of the IWMA. "Whatever turn the impending horrid war may take, the alliance of the working classes of all countries will ultimately kill war. The very fact that while official France and Germany are rushing into a fratricidal feud, the workmen of France and Germany send each other messages of peace and goodwill; this great fact, unparalleled in the history of the past, opens the vista of a brighter future. It proves that in contrast to old society, with its economical miseries and its political delirium, a new society is springing up, whose International rule will be Peace, because its natural ruler will be everywhere the same - Labour! The Pioneer of that new society is the International Working Men's Association." (20)

Peace activists, John Stuart Mill and John Morley, congratulated Marx on his statement and arranged for 30,000 copies of his speech to be printed and distributed. Marx thought the war would provide the opportunity for revolution. He told Engels: "I have been totally unable to sleep for four nights now, on account of the rheumatism and I spend this time in fantasies about Paris, etc." He hoped for a German victory: "I wish this because the definite defeat of Bonaparte is likely to provoke Revolution in France, while the definite defeat of Germany would only protract the present state of things for twenty-years." (21)

In a letter to the American organiser of the IWMA, Friedrich Sorge, Marx made some predictions about the future that included the First World War and the Russian Revolution: "What the Prussian jackasses do not see is that the present war is leading... inevitably to a war between Germany and Russia. And such a war No.2 will act as the midwife of the inevitable social revolution in Russia." (22)

The war went badly for Napoleon III and he was heavily defeated at the Battle of Sedan. On 4th September, 1870, a republic was proclaimed in Paris. Adolphe Thiers, a former prime minister and an opponent of the war, was elected chief executive of the new French government. (23)

Thiers, now aged 74, appointed a provisional government of conservative views and then travelled to London and attempted to negotiate an alliance with Britain. William Gladstone refused and when he arrived back in Paris on 31st October 1870, he was accused of treason. Felix Pyat, a radical socialist organized demonstrations against Thiers, whom he accused of threatening to sell France to the Germans. (24)

Karl Marx, who had been slow to attack Bismark because of his "pure German patriotism to which both he and Engels were always conspicuously prone" and the International Workingmen's Association issued a statement "protesting against the annexation, denouncing the dynastic ambitions of the Prussian King, and calling upon the French workers to unite with all defenders of democracy against the common Prussian foe." (25)

Marx later pointed out that it was "An absurdity and an anachronism to make military considerations the principle by which the boundaries of nations are to be fixed? If this rule were to prevail, Austria would still be entitled to Venetia and the line of the Minicio, and France to the line of the Rhine, in order to protect Paris, which lies certainly more open to an attack from the northeast than Berlin does from the southwest. If limits are to be fixed by military interests, there will be no end to claims, because every military line is necessarily faulty, and may be improved by annexing some more outlying territory; and, moreover, they can never be fixed finally and fairly, because they always must be imposed by the conqueror upon the conquered, and consequently carry within them the seed of fresh wars." (26)

In March 1871, the government made an attempt to disarm the Paris National Guard, a volunteer citizen force which showed signs of radical sympathies. It refused to give up its arms, declared its autonomy, deposed the officials of the provisional government, and elected a revolutionary committee of the people as the true government of France. Adolphe Thiers now fled to Versailles. Governments all over Europe were concerned by what was happening in Europe. The Times reported complained against "this dangerous sentiment of the Democracy, this conspiracy against civilisation in its so-called capital". (27)

The new government called itself the Paris Commune and attempted to run the city. Isaiah Berlin argues the committee was a mixture of different political opinions but did include the followers of Mikhail Bakunin, Pierre-Joseph Proudhon and Louis Auguste Blanqui. The Communards had difficulty keeping control of the national guard and 28th March, on the day of the election, General Jacques Leon Clément-Thomas and General Claude Lecomte were murdered. Doctor Guyon, who examined the bodies shortly afterwards, found forty balls in the body of Clément-Thomas and nine balls in the back of Lecomte.

Adolphe Thiers now based in Versailles urged Parisians to abstain from voting. When the voting was finished, 233,000 Parisians had voted, out of 485,000 registered voters. In upper-class neighborhoods many refused to take part in the election with over 70 per cent refusing to vote. But in the working-class neighborhoods, turnout was high. Of the ninety-two Communards elected by popular suffrage, seventeen were members of the IWA. It was agreed that Marx should draft an "Address to the People of Paris" but he was suffering from bronchitis and liver trouble and was unable to carry out the work. (28)

The Communards had difficulty keeping control of the national guard and on the day of the election, General Jacques Leon Clément-Thomas and General Claude Lecomte , two men blamed for being severe disciplinarians, were murdered. Doctor Guyon, who examined the bodies shortly afterwards, found forty balls in the body of Clément-Thomas and nine balls in the back of Lecomte. (29)

At the first meeting of the Commune, the members adopted several proposals, including an honorary presidency for Louis Auguste Blanqui; the abolition of the death penalty; the abolition of military conscription; a proposal to send delegates to other cities to help launch communes there. It was also stated that no military force other than the National Guard, made up of male citizens, could be formed or introduced into the capital. School children in the city were provided with free clothing and food. David McLellan suggests that the actual measures passed by the commune were reformist rather than revolutionary, with no attack on private property: employers were forbidden on the penalty of fines to reduce wages... and all abandoned businesses were transferred to co-operative associations." (30)

Karl Marx believed the actions of the Communards were revolutionary: "Having once got rid of the standing army and the police – the physical force elements of the old government – the Commune was anxious to break the spiritual force of repression... by the disestablishment and disendowment of all churches as proprietary bodies. The priests were sent back to the recesses of private life, there to feed upon the alms of the faithful in imitation of their predecessors, the apostles. The whole of the educational institutions were opened to the people gratuitously, and at the same time cleared of all interference of church and state. Thus, not only was education made accessible to all, but science itself freed from the fetters which class prejudice and governmental force had imposed upon it." (31)

Although only males were allowed to vote in the elections, several women were involved in the Paris Commune. Nathalie Lemel and Élisabeth Dmitrieff, created the Women's Union for the Defense of Paris and Care of the Wounded. The group demanded gender and wage equality, the right of divorce for women, the right to secular education, and professional education for girls. Anne Jaclard and Victoire Léodile Béra founded the newspaper Paris Commune and Louise Michel, established a female battalion of the National Guard. (32)

The Committee was given extensive powers to hunt down and imprison enemies of the Commune. Led by Raoul Rigault, it began to make several arrests, usually on suspicion of treason. Those arrested included Georges Darboy, the Archbishop of Paris, General Edmond-Charles de Martimprey and Abbé Gaspard Deguerry. Rigault attempted to exchange these prisoners for Louis Auguste Blanqui who had been captured by government forces. Despite lengthy negotiations, Adolphe Thiers refused to release him.

On 22nd May 1871, Marshal Patrice de MacMahon and his government troops entered the city. The Committee of Public Safety issued a decree: "To arms! That Paris be bristling with barricades, and that, behind these improvised ramparts, it will hurl again its cry of war, its cry of pride, its cry of defiance, but its cry of victory; because Paris, with its barricades, is undefeatable ...That revolutionary Paris, that Paris of great days, does its duty; the Commune and the Committee of Public Safety will do theirs!" (33)

It is estimated that about fifteen to twenty thousand persons, including many women and children, responded to the call of arms. The forces of the Commune were outnumbered five-to-one by Marshal MacMahon's forces. They made their way to Montmartre, where the uprising had begun. The garrison of one barricade, was defended in part by a battalion of about thirty women, including Louise Michel. The soldiers captured 42 guardsmen and several women, took them to the same house on Rue Rosier where generals Clement-Thomas and Lecomte had been executed, and shot them.

Large numbers of the National Guard changed into civilian clothes and fled the city. It is estimated that this left only about 12,000 Communards to defend the barricades. As soon as they were captured they were executed. Raoul Rigaut responded by killing his prisoners, including the Archbishop of Paris and three priests. Soon afterwards Rigaut was captured and executed and the rebellion came to an end soon afterwards on 28th May. As Isaiah Berlin pointed out: "The retribution which the victorious army exacted took the form of mass executions; the white terror, as is common in such cases, far outdid in acts of bestial cruelty the worst excesses of the regime whose misdeeds it had come to end." (34)

According to Karl Marx this is what always happens when the masses attempt to take control of society: "The civilization and justice of bourgeois order comes out in its lurid light whenever the slaves and drudges of that order rise against their masters. Then this civilization and justice stand forth as undisguised savagery and lawless revenge. Each new crisis in the class struggle between the appropriator and the producer brings out this fact more glaringly... The self-sacrificing heroism with which the population of Paris – men, women, and children – fought for eight days after the entrance of the Versaillese, reflects as much the grandeur of their cause, as the infernal deeds of the soldiery reflect the innate spirit of that civilization, indeed, the great problem of which is how to get rid of the heaps of corpses it made after the battle was over!" (35)

In his best-selling pamphlet, The Civil War in France (1871), Karl Marx admitted that the International Workingmen's Association was heavily involved in the Paris Commune. Jules Favre, the recently reinstated foreign minister in France, asked all European governments to outlaw the IWMA. A French newspaper identified Marx as the "supreme chief" of the conspirators, alleging that he had "organised" the uprising from London. It claimed that the IWMA had seven million members. (36)

Other European governments also urged the punishment of IWMA members. Spain agreed to extradite those involved in the Paris Commune. Giuseppe Mazzini, the leader of the Italian nationalist movement, joined in the calls for the arrest of Marx, who he described as "a man of domineering disposition; jealous of the influence of others; governed by no earnest, philosophical, or religious belief; having, I fear more elements of anger than of love in his nature". (37)

British newspapers also complained about the dangers posed by Karl Marx. The Times warned of the possibility of Marx having an influence on the working-class. It feared that solid English trade unionists who wanted nothing more than "a fair day's wage for a fair day's work" might be corrupted by "strange theories" imported from abroad. (38) Marx wrote to Ludwig Kugelmann that "I have the honour to be this moment the most abused and threatened man in London." (39)

The German ambassador urged Granville Leveson-Gower, the British Foreign Secretary, to treat Marx as a common criminal because of his outrageous "menaces to life and property". After consulting with William Gladstone, the Prime Minister, he replied that "extreme socialist opinions are not believed to have gained any hold upon the working men of this country" and "no practical steps with regard to foreign countries are known to have been taken by the English branch of the Association." (40)

The publication of The Civil War in France (1871) upset several British trade union leaders and George Odger resigned from the General Council of International Workingmen's Association. It has been argued that the passing of the 1867 Reform Act had made the working class less radical. After the Paris Commune, the only areas where the IWMA made progress was in the the strongholds of anarchism: Spain and Italy. (41)

Conflict with the Anarchists

In March 1869 Mikhail Bakunin met Sergi Nechayev. Soon afterwards Bakunin wrote to James Guillaume that: "I have here with me one of those young fanatics who know no doubts, who fear nothing, and who realize that many of them will perish at the hands of the government but who nevertheless have decided that they will not relent until the people rise. They are magnificent, these young fanatics, believers without God, heroes without rhetoric." (42)

Later that year Bakunin and Nechayev co-wrote Catechism of a Revolutionist. It included the famous passage: "The Revolutionist is a doomed man. He has no private interests, no affairs, sentiments, ties, property nor even a name of his own. His entire being is devoured by one purpose, one thought, one passion - the revolution. Heart and soul, not merely by word but by deed, he has severed every link with the social order and with the entire civilized world; with the laws, good manners, conventions, and morality of that world. He is its merciless enemy and continues to inhabit it with only one purpose - to destroy it." (43)

Nechayev set up a secret terrorist organization, People's Retribution, and claimed he was an agent of the IWA. Karl Marx was appalled by this and at a special conference held in September 1871, held at a pub off Tottenham Court Road. Marx dominated the proceedings and a motion was passed that pointed out that Nechayev "has fraudulently used the name of the International Working Men's Association in order to make dupes and victims in Russia". (44)

Bakunin continued to work closely with Nechayev and Marx was appalled when he discovered that a publisher who had decided to publish a Russian edition of Das Kapital had received death threats from the young Russian. Bakunin had been paid an advance of 300 roubles to translate the book into Russian. He began the task but then decided against finishing the project. When the publisher asked for his money back Nechayev wrote to him suggesting that if he did not withdraw his demands he would have to be killed. (45)

Marx attempted to infuse English workers with "internationalism and the revolutionary spirit". He was unsuccessful in this task and criticised the trade unions being an "aristocratic minority" and not involving "lower-paid workers, to whom, together with the Irish, Marx increasingly looked for support." However, the followers of Victoria Woodhull in America, and the IWMA sections in France, Spain and Italy, complained about Marx was dominating the organization. The opposition issued a circular denouncing "authoritarianism and hierarchy" in the IWMA. There was now a split between the "anti-authoritarians" and the groups that adhered to the General Council. (46)

Marx attended the IWMA National Congress at the Hague, in September, 1872. According to newspaper reports, local people were warned "not to go into the streets with articles of value upon them" as the "International is coming and will steal them". Vast crowds followed the delegates from the railway station to the hotel, "the figure of Karl Marx attracting special attention". Marx dominating the proceedings "his black broadcloth suit contrasted with his white hair and beard and he would screw a monocle into his eye when he wanted to scrutinise his audience." (47)

At the congress a report was presented that showed Mikhail Bakunin had tried to establish a secret society within the IWMA and was also guilty of fraud. It also revealed details of the letter sent by Sergi Nechayev to Marx's publisher in Russia. The delegates voted twenty-seven votes to seven, that Bakunin should be expelled from the association. (48)

Marx had decided to retire from the IWMA and concentrate on the second volume of Das Kapital. Marx decided that the General Council of the IWMA should be moved to America. Engels proposed at the congress that the organisation should be transferred to New York City. The vote was very close with twenty-six for, twenty-three against and 9 abstentions. (49)

The rival anarchists held a rival congress immediately following the IWMA congress. In 1873 they had another congress that was attended by anarchists from England, Italy, Spain, Switzerland, Belgium and the Netherlands.

Friedrich Sorge now became general secretary of the International Workingmen's Association. The General Council in New York attempted to organise a congress in Geneva in 1873, but it was poor attended after Marx instructed his followers not to attend. Marx wrote in 1874 that "in England the International is for the time being as good as dead". (50) However, it was not until 1876 that the IWMA was officially dissolved. After this it became known as the First International. (51)

Primary Sources

(1) Yuri Mikhailovich Steklov, History Of The First International (1928)

The economic crisis of 1857 and the political crisis of 1859 culminated in the Franco-Austrian War (the War of Italian Independence), and there ensued a general awakening alike of the bourgeoisie and of the proletariat in the leading European lands. In Great Britain there was superadded the influence of the American Civil War (1861-4), for this led to a crisis in the cotton trade, which involved the British textile workers in terrible distress. This economic crisis, which began towards the close of the fifties speedily put an end to the idyllic dreams that had followed the defeat of Chartism. After the decline of the revolutionary ferment characteristic of the palmy days of the Chartist movement there had ensued an era in which moderate liberalism had prevailed among the British workers. Now, this liberalism sustained a severe, and, at the time it seemed, a decisive blow. There came a period of incessant strikes, many of them declared in defiance of the moderate leaders, who were enthroned in the trade union executives. In numerous cases these strikes were settled by collective bargains (“working rules”), then a new phenomenon, but destined in the future to secure a wide vogue.

Although many of the strikes were unsuccessful, they favoured the growth of working-class solidarity. Such was certainly the effect of the famous strike in the London building trade during the years 1859 and 1860, which occurred in connexion with the struggle for a nine-hour day, and culminated in a lock-out. At this time, a new set of working-class leaders began to come to the front-men permeated with the fighting spirit of the hour, and aiming at the unification of the detached forces of the workers. Such a process of unification was assisted by the steady growth of the “trades councils” which sprang to life in all the great centres of industry during the decade from 1858 to 1867. These councils, which were often formed as the outcome of strikes, or in defence of the general interests of trade unionism, integrated the local movements, and to a notable extent promoted the organisation of the proletariat.

(2) Karl Marx, The General Rules he International Workingmen's Association (October 1864)

That the emancipation of the working classes must be conquered by the working classes themselves, that the struggle for the emancipation of the working classes means not a struggle for class privileges and monopolies, but for equal rights and duties, and the abolition of all class rule;That the economical subjection of the man of labor to the monopolizer of the means of labor – that is, the source of life – lies at the bottom of servitude in all its forms, of all social misery, mental degradation, and political dependence;

That the economical emancipation of the working classes is therefore the great end to which every political movement ought to be subordinate as a means;

That all efforts aiming at the great end hitherto failed from the want of solidarity between the manifold divisions of labor in each country, and from the absence of a fraternal bond of union between the working classes of different countries;

That the emancipation of labor is neither a local nor a national, but a social problem, embracing all countries in which modern society exists, and depending for its solution on the concurrence, practical and theoretical, of the most advanced countries;

That the present revival of the working classes in the most industrious countries of Europe, while it raises a new hope, gives solemn warning against a relapse into the old errors, and calls for the immediate combination of the still disconnected movements;

For these reasons –

The International Working Men's Association has been founded.

It declares:

That all societies and individuals adhering to it will acknowledge truth, justice, and morality as the basis of their conduct toward each other and toward all men, without regard to color, creed, or nationality;

That it acknowledges no rights without duties, no duties without rights;

And, in this spirit, the following Rules have been drawn up.

This Association is established to afford a central medium of communication and co-operation between workingmen's societies existing in different countries and aiming at the same end; viz., the protection, advancement, and complete emancipation of the working classes.

The name of the society shall be "The International Working Men's Association."

There shall annually meet a General Working Men's Congress, consisting of delegates of the branches of the Association. The Congress will have to proclaim the common aspirations of the working class, take the measures required for the successful working of the International Association, and appoint the General Council of the society.

Each Congress appoints the time and place of meeting for the next Congress. The delegates assemble at the appointed time and place, without any special invitation. The General Council may, in case of need, change the place, but has no power to postpone the time of the General Council annually. The Congress appoints the seat and elects the members of the General Council annually. The General Council thus elected shall have power to add to the number of its members.

On its annual meetings, the General Congress shall receive a public account of the annual transactions of the General Council. The latter may, in case of emergency, convoke the General Congress before the regular yearly term.

The General Council shall consist of workingmen from the different countries represented in the International Association. It shall, from its own members, elect the officers necessary for the transaction of business, such as a treasurer, a general secretary, corresponding secretaries for the different countries, etc.

The General Council shall form an international agency between the different and local groups of the Association, so that the workingmen in one country be consistently informed of the movements of their class in every other country; that an inquiry into the social state of the different countries of Europe be made simultaneously, and under a common direction; that the questions of general interest mooted in one society be ventilated by all; and that when immediate practical steps should be needed – as, for instance, in case of international quarrels – the action of the associated societies be simultaneous and uniform. Whenever it seems opportune, the General Council shall take the initiative of proposals to be laid before the different national or local societies. To facilitate the communications, the General Council shall publish periodical reports.

Since the success of the workingmen's movement in each country cannot be secured but by the power of union and combination, while, on the other hand, the usefulness of the International General Council must greatly depend on the circumstance whether it has to deal with a few national centres of workingmen's associations, or with a great number of small and disconnected local societies – the members of the International Association shall use their utmost efforts to combine the disconnected workingmen's societies of their respective countries into national bodies, represented by central national organs. It is self-understood, however, that the appliance of this rule will depend upon the peculiar laws of each country, and that, apart from legal obstacles, no independent local society shall be precluded from corresponding directly with the General Council.

Every section has the right to appoint its own secretary corresponding directly with the General Council.

Everybody who acknowledges and defends the principles of the International Working Men's Association is eligible to become a member. Every branch is responsible for the integrity of the members it admits.

Each member of the International Association, on removing his domicile from one country to another, will receive the fraternal support of the Associated Working Men.

While united in a perpetual bond of fraternal co-operation, the workingmen's societies joining the International Association will preserve their existent organizations intact.

The present Rules may be revised by each Congress, provided that two-thirds of the delegates present are in favor of such revision.

Everything not provided for in the present Rules will be supplied by special Regulations, subject to the revision of every Congress.

(3) Karl Marx, The Civil War in France (1871)

While the European governments thus testify, before Paris, to the international character of class rule, they cry down the International Working Men’s Association – the international counter-organization of labor against the cosmopolitan conspiracy of capital – as the head fountain of all these disasters. Thiers denounced it as the despot of labor, pretending to be its liberator. Picard ordered that all communications between the French Internationals and those abroad be cut off; Count Jaubert, Thiers’ mummified accomplice of 1835, declares it the great problem of all civilized governments to weed it out. The Rurals roar against it, and the whole European press joins the chorus.

An honorable French writer, completely foreign to our Association, speaks as follows: "The members of the Central Committee of the National Guard, as well as the greater part of the members of the Commune, are the most active, intelligent, and energetic minds of the International Working Men’s Association... men who are thoroughly honest, sincere, intelligent, devoted, pure, and fanatical in the good sense of the word."

The police-tinged bourgeois mind naturally figures to itself the International Working Men’s Association as acting in the manner of a secret conspiracy, its central body ordering, from time to time, explosions in different countries. Our Association is, in fact, nothing but the international bond between the most advanced working men in the various countries of the civilized world. Wherever, in whatever shape, and under whatever conditions the class struggle obtains any consistency, it is but natural that members of our Association, should stand in the foreground. The soil out of which it grows is modern society itself. It cannot be stamped out by any amount of carnage. To stamp it out, the governments would have to stamp out the despotism of capital over labor – the condition of their own parasitical existence.

Student Activities

Child Labour Simulation (Teacher Notes)

Richard Arkwright and the Factory System (Answer Commentary)

Robert Owen and New Lanark (Answer Commentary)

James Watt and Steam Power (Answer Commentary)

The Domestic System (Answer Commentary)