Katherine Anne Porter

Katherine Anne Porter, the fourth of five children of Harrison Boone Porter and Alice Jones Porter, was born in Indian Creek, Texas, on 15th May, 1890. Her mother died giving birth to her fifth child two years later. Katherine and the other children went to live with her father's mother in Kyle.

Porter later admitted that when she was a young child she kept on running away. "I never got very far, but they were always having to come and fetch me." On one occasion he asked her, "Why are you so restless? Why can’t you stay here with us?" and she replied, “I want to go and see the world. I want to know the world like the palm of my hand.”

Porter explained in an interview in 1963: "We were brought up with a sense of our own history, you know. My mother’s family came to this country in 1648 and went to the John Randolph territory of Virginia. And one of my great-great-grandfathers was Jonathan Boone, the brother of Daniel. On my father’s side I’m descended from Colonel Andrew Porter, whose father came to Montgomery County, Pennsylvania, in 1720. He was one of the circle of George Washington during the Revolution, a friend of Lafayette, and one of the founders of the Society of the Cincinnati."

Porter was very close to her grandmother but unfortunately she died when she was only eleven years-old. Harrison Porter now took the children to live with relatives in Louisiana. They then moved to San Antonio, where she attended the Thomas School, a private Methodist school in 1904. However, because the family were always on the move she received very little formal education.

When Porter was only sixteen years-old she married John Henry Koontz, the son of a wealthy ranching family in Lufkin. Koontz was violent towards her and in 1914 she escaped to Chicago, where she worked as a singer and actress. "I sang old Scottish ballads in costume - I made it myself - all around Texas and Louisiana." However, in 1915 she was diagnosed with tuberculosis and spent six weeks in a sanatorium. It was during this period that she decided to become a writer.

Porter later recalled: "I started out with nothing in the world but a kind of passion, a driving desire. I don’t know where it came from, and I don’t know why - or why I have been so stubborn about it that nothing could deflect me. But this thing between me and my writing is the strongest bond I have ever had - stronger than any bond or any engagement with any human being or with any other work I’ve ever done. I really started writing when I was six or seven years old.... All the old houses that I knew when I was a child were full of books, bought generation after generation by members of the family. Everyone was literate as a matter of course. Nobody told you to read this or not to read that. It was there to read, and we read... I was reading Shakespeare’s sonnets when I was thirteen years old, and I’m perfectly certain that they made the most profound impression upon me of anything I ever read."

In 1917 Porter began writing for the Fort Worth Critic . The following year she switched to the Rocky Mountain News in Denver, Colorado. This came to an end when she was a victim of the 1918 influenza pandemic. When she was discharged from the hospital she was completely bald. When her hair finally grew back, it was white, and remained that color for the rest of her life.

Porter now moved to Greenwich Village in New York City. She found work writing children's stories. Porter became active in politics and for a time worked for a magazine publisher in Mexico. "I went to Mexico because I felt I had business there. And there I found friends and ideas that were sympathetic to me. That was my entire milieu. I don’t think anyone even knew I was a writer. I didn’t show my work to anybody or talk about it, because - well, no one was particularly interested in that. It was a time of revolution, and I was running with almost pure revolutionaries!"

Porter published her first story, María Concepción , in Century Magazine in 1923: "I don’t think I learned very much from my contemporaries. To begin with, we were all such individuals, and we were all so argumentative and so bent on our own courses that although I got a kind of support and personal friendship from my contemporaries, I didn’t get very much help. I didn’t show my work to anybody. I didn’t hand it around among my friends for criticism, because, well, it just didn’t occur to me to do it. Just as I didn’t even try to publish anything until quite late because I didn’t think I was ready. I published my first story in 1923. That was María Concepción, the first story I ever finished. I rewrote María Concepción fifteen or sixteen times. That was a real battle, and I was thirty-three years old. I think it is the most curious lack of judgment to publish before you are ready. If there are echoes of other people in your work, you’re not ready. If anybody has to help you rewrite your story, you’re not ready. A story should be a finished work before it is shown. And after that, I will not allow anyone to change anything, and I will not change anything on anyone’s advice."

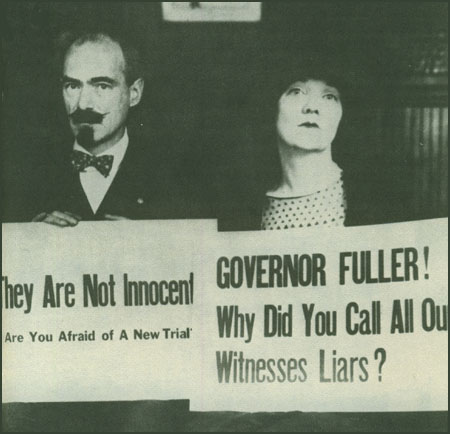

Porter was active in the campaign to free Bartolomeo Vanzetti and Nicola Sacco. They were convicted for murdering Frederick Parmenter and Alessandro Berardelli during a robbery in 1920. In 1927 Governor Alvan T. Fuller appointed a three-member panel of Harvard President Abbott Lawrence Lowell, the President of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Samuel W. Stratton, and the novelist, Robert Grant to conduct a complete review of the case and determine if the trials were fair. The committee reported that no new trial was called for and based on that assessment Governor Fuller refused to delay their executions or grant clemency. Walter Lippmann, who had been one of the main campaigners for Sacco and Vanzetti, argued that Governor Fuller had "sought with every conscious effort to learn the truth" and that it was time to let the matter drop.

It now became clear that Sacco and Vanzetti would be executed. Heywood Broun was furious and on 5th August 1927 he wrote in New York World: "Alvan T. Fuller never had any intention in all his investigation but to put a new and higher polish upon the proceedings. The justice of the business was not his concern. He hoped to make it respectable. He called old men from high places to stand behind his chair so that he might seem to speak with all the authority of a high priest or a Pilate. What more can these immigrants from Italy expect? It is not every prisoner who has a President of Harvard University throw on the switch for him. And Robert Grant is not only a former Judge but one of the most popular dinner guests in Boston. If this is a lynching, at least the fish peddler and his friend the factory hand may take unction to their souls that they will die at the hands of men in dinner coats or academic gowns, according to the conventionalities required by the hour of execution."

Katherine Anne Porter decided to travel to Boston to take part in the demonstrations against the proposed execution of Bartolomeo Vanzetti and Nicola Sacco. Other campaigners who had arrived in the city included Dorothy Parker, Ruth Hale, John Dos Passos, Susan Gaspell, Edna St. Vincent Millay, Mary Heaton Vorse, Upton Sinclair, Michael Gold, Paxton Hibben and Sender Garlin.

Porter continued to publish short-stories and in 1930, she published her first short story collection, Flowering Judas and Other Stories. The book was highly praised by the critics and Elizabeth Hardwick has argued that the strength of her stories was in their "extraordinary simplicity and freshness". This was followed by Pale Horse, Pale Rider (1939).

Porter was briefly married to Ernest Stock. After contracting gonorrhea from him, she had a hysterectomy, ending her hopes of ever having a child. In 1930, she married Eugene Pressley, a writer thirteen years her junior. Porter also claims to have married Hart Crane in 1932, just before he committed suicide. In 1938 she married Albert Russel Erskine, Jr., a student who was in his twenties. He reportedly divorced her in 1942 after discovering her real age.

After the Second World War she taught at Stanford University, the University of Michigan, Washington and Lee University, and the University of Texas. Porter was considered an expert on modern literature and appeared on radio and television discussing authors such as Virginia Woolf, Rebecca West, E. M. Forster, Gertrude Stein and William Styron. It has been claimed that she has influenced several writers including Kay Boyle, Tillie Olsen and Eudora Welty.

Porter began work on her only novel, Ship of Fools: "I went up and sat nearly three years in the country, and while I was writing it I worked every day, anywhere from three to five hours. Oh, it’s true I used to do an awful lot of just sitting there thinking what comes next, because this is a great big unwieldy book with an enormous cast of characters - it’s four hundred of my manuscript pages, and I can get four hundred and fifty words on a page. But all that time in Connecticut, I kept myself free for work: no telephone, no visitors - oh, I really lived like a hermit, everything but being fed through a grate... I can live a solitary life for months at a time, and it does me good, because I’m working. I just get up bright and early - sometimes at five o’clock - have my black coffee, and go to work."

Ship of Fools was published in 1962. The story tells of a group of characters sailing from Mexico to Europe aboard a German freighter and passenger ship. It is an allegory that traces the rise of fascism in Nazi Germany under Adolf Hitler. Despite a mixed reception from the critics it outsold every other American novel published that year. The film rights were sold for $500,000 ($3,794,829 adjusted for inflation). Directed by Stanley Kramer, the film starred Vivien Leigh, Simone Signoret, José Ferrer, Lee Marvin, Oskar Werner, Michael Dunn, Elizabeth Ashley, George Segal, José Greco and Heinz Rühmann.

In 1966 she was awarded the Pulitzer Prize and the U.S. National Book Award for The Collected Stories of Katherine Anne Porter, and that year was also appointed to the American Academy of Arts and Letters. The Collected Essays and Occasional Writings of Katherine Anne Porter was published in 1970. Porter published The Never-Ending Wrong, an account of the trial and execution of Bartolomeo Vanzetti and Nicola Sacco in 1977.

Katherine Anne Porter died in Silver Spring, Maryland on 18th September, 1980.

Primary Sources

(1) Katherine Anne Porter, The Paris Review (1963)

Any true work of art has got to give you the feeling of reconciliation—what the Greeks would call catharsis, the purification of your mind and imagination—through an ending that is endurable because it is right and true. Oh, not in any pawky individual idea of morality or some parochial idea of right and wrong. Sometimes the end is very tragic, because it needs to be. One of the most perfect and marvelous endings in literature - it raises my hair now - is the little boy at the end of Wuthering Heights, crying that he’s afraid to go across the moor because there’s a man and woman walking there.

And there are three novels that I reread with pleasure and delight - three almost perfect novels, if we’re talking about form, you know. One is A High Wind in Jamaica by Richard Hughes, one is A Passage to India by E. M. Forster, and the other is To the Lighthouse by Virginia Woolf. Every one of them begins with an apparently insoluble problem, and every one of them works out of confusion into order. The material is all used so that you are going toward a goal. And that goal is the clearing up of disorder and confusion and wrong, to a logical and human end. I don’t mean a happy ending, because after all at the end of A High Wind in Jamaica the pirates are all hanged and the children are all marked for life by their experience, but it comes out to an orderly end. The threads are all drawn up. I have had people object to Mr. Thompson’s suicide at the end of Noon Wine, and I’d say, “All right, where was he going? Given what he was, his own situation, what else could he do?” Every once in a while when I see a character of mine just going towards perdition, I think, Stop, stop, you can always stop and choose, you know. But no, being what he was, he already has chosen, and he can’t go back on it now. I suppose the first idea that man had was the idea of fate, of the servile will, of a deity who destroyed as he would, without regard for the creature. But I think the idea of free will was the second idea.