Igor Gouzenko

Igor Gouzenko was born in Rogachovo, Russia on 13th January, 1922. He worked as a cipher clerk at the Soviet Military Intelligence (GRU) in Moscow. "I had a desk in what had been the ballroom of a pre-revolutionary mansion. There were about 40 of us at a time working in three shifts." (1)

Gouzenko joined the Russian Legation in Ottawa, Canada in 1943. (2) This was only a cover as he was really a KGB intelligence officer. According to Benjamin de Forest Bayly: "The military attaché at the Soviet embassy got Gouzenko to decode one of his messages because he didn't feel like doing it himself. When Gouzenko decoded it he saw it was instructions for him to be sent back to the Soviet Union, because he wasn't trusted." His wife advised him to: "Go into the vault and steal every secret thing you can put your hands on, and change the combination on the vault and lock the door. It'll take six weeks for the Russians to send somebody over to chisel the door of the safe open to find out you've taken all these things. Turn yourself over to the Canadians." (3)

Over the next few weeks he started taking home secret documents. Gouzenko left the Soviet embassy on 5th September, 1945. He later wrote: "There were almost a hundred documents, some of them small scraps of paper and others covering several large sheets of stationary... The documents felt like they weighed a ton and I imagined that they were bulging out from under my shirt." (4) The following day he went to the Justice Department. However, he was turned away and he decided to take his story to Ottawa Journal. (5) With their help he was interviewed by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP).

Defection of Igor Gouzenko

The next morning Norman Robertson, Undersecretary of State for External Affairs, had a meeting with Prime Minister Mackenzie King. He explained that Gouzenko had claimed that he had documents showing that the Soviets had spies in Canada and the United States and that "some of these men were around" Edward Stettinius, the U.S. Secretary of State. King wrote in his diary that "Robertson seemed to feel that the information might be so important both to the States... and to Britain that it would be in their interests to seize it no matter how it was obtained." King was worried that taking these documents might cause political problems in the future. "I said to Robinson... that I thought we should be extremely careful in becoming a party to any course of action which would link the government of Canada up with this matter in a manner which might cause Russia to feel that we had performed an unfriendly act. That to seek to gather information in any underhand way would make clear that we did not trust the Embassy... My own feeling is that the individual has incurred the displeasure of the Embassy and is really seeking to shield himself." (6)

Amy W. Knight, the author of How the Cold War Began (2005), has pointed out: "King would later be criticized for not immediately grasping the importance of what the defector had to offer and for his naivety in trusting the Soviets. But his reaction was understandable. Apart from wishing to avoid a diplomatic debacle, King also questioned the motives of the potential defector. The man was quite possibly lying to save his own skin, or because he wanted to live in Canada and needed a means to gain asylum. Whatever the case, King was not about to allow a Soviet code clerk to disrupt the cordial diplomacy that had characterized Ottawa's relations with Moscow." (7)

William Stephenson

It was later pointed out that William Stephenson, the head of British Security Coordination, was involved in Gouzenko's defection. He "argued strongly against King's view that Gouzenko should be ignored. The Russian, he said, would certainly have information valuable not merely to Canada but also to Britain, the United States, and other Allies. Furthermore, Gouzenko's life was almost certainly in danger. They should act, and do so immediately, by taking Gouzenko in." (8)

Stephenson arranged for Gouzenko to be taken into protective custody. He was then transferred to Camp X, where he and his wife lived in guarded seclusion. Later two former BSC agents interviewed him. He claiming he had evidence of an Soviet spy ring in Canada. Gouzenko provided evidence that led to the arrest of 22 local agents and 15 Soviet spies in Canada. This included Agatha Chapman, Fred Rose, Sam Carr, Raymond Boyer, Edward Mazerall, Gordon Lunan, and Kathleen Willsher. Information from Gouzenko also resulted in the arrest and conviction of Klaus Fuchs and Allan Nunn May.

Kim Philby

The case was passed on to Kim Philby, head of Section IX (Soviet Affairs) of MI6. Philby later recalled: "The first information about Gouzenko and Elli came from Stephenson. "C" (Stewart menzies) called me in and asked me my opinion about it. I said Gouzenko's defection was obviously very important and we treated it as such. But it was a disaster for the KGB and there was no way I could help. The Mounties had Gouzenko so well protected that it was impossible for the Russians to do anything about him, bump him off or anything like that. So he was able to give away a big Canadian network, and the telegrams he brought with him when he defected would have been of great help to Western decrypters." (9)

By 17th September Philby was reporting what Gouzenko was telling BSC. "Stanley (Philby) reports that he managed to learn details of the information turned over to Canada by the traitor Gouzenko... As a result of these affairs the British intelligence and counter-intelligence organs are undoubtedly going to take effective measures soon against illegal activity by fraternal and Soviet intelligence." (10)

Philby was expected to go to Canada but instead he sent Roger Hollis. It has been argued by Ben Macintyre, the author of A Spy Among Friends (2014), the reason for this was that he feared Gouzenko was about to expose him as a Soviet spy. "He (Philby) waited anxiously for the results of Gouzenko's debriefing. Philby may have contemplated defection to the Soviet Union. The defector exposed a major spy network in Canada, and revealed that the Soviets had obtained information about the atomic bomb project from a spy working at the Anglo-Canadian nuclear research laboratory in Montreal. But Gouzenko worked for the GRU, Soviet military intelligence, not the NKVD; he knew little about Soviet espionage in Britain." (11)

Gouzenko told the investigators that when he was working in Moscow he discovered that the GRU had an important spy based in London with the code name "Elli". Apparently Elli's information was considered so important that as soon as the information came in from him it was taken immediately to Joseph Stalin. Gouzenko told Chapman Pincher: "I sat next to my friend Lieutenant Luibimov and one day he passed me a telegram he had deciphered from the Soviet Embassy in London. He said it came from a spy right inside British counter-intelligence in England. The spy's code-name in the secret radio traffic between London and Moscow was Elli." (12) Gouzenko also claimed that when it was decided to send the senior MI5 officer, Guy Liddell to Ottawa in 1944 to discuss security issues with Canadian Intelligence, this information was leaked by someone based in London. (13)

A report written in September 1945 stated that "(Gouzenko) states that while he was in the Central Code Section in Moscow in 1942... he heard about a Soviet agent in England, allegedly a member of the British Intelligence Service. This agent, who was of Russian descent, had reported that the British had a very important agent of their own in the Soviet Union, who was apparently being run by someone in Moscow... When the message arrived it was received by a Lt. Col. Polakova who, in view of its importance, immediately got in touch with Stalin himself by telephone." (14)

Life in Canada

Gouzenko and his family were given another identity by the Canadian government out of fear of Soviet reprisals. He later wrote about the reasons why he defected: "During my residence in Canada, I have seen how the Canadian people and their government, sincerely wishing to help the Soviet people sent supplies to the Soviet Union, collected money for the welfare of the Russian people, sacrificing the lives of their sons in the delivery of supplies across the ocean - and instead of gratitude for the help rendered, the Soviet government is developing espionage activity in Canada, preparing to deliver a stab in the back to Canada - all this without the knowledge of the Russian people." (15)

Gouzenko was given a house and two acres of land in Port Credit, Ontario, a small lakeside town west of Toronto. The Canadian government provided them with a new identity and cover stories that accounted for their thickly accented English. They were now Czech immigrants, Stanley and Anna Krysac. (16) They also a RCMP guard living with them. However, the Canadian security services still feared that the Soviets would find a way to assassinate him. The RCMP Commissioner Stuart Wood wrote to the Minister of Justice in October 1947, complaining that "Gouzenko's disregard for advice and the manner in which he persisted in doing things his own way, regardless of security, were bound to expose him within a short period of time." (17)

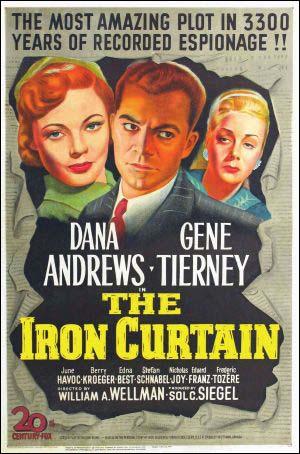

Gouzenko began work with two journalists on an account of his defection. The book, This Was My Choice, appeared in 1949. However, he was not allowed to give any details of the information that he had given to Western intelligence agencies. The book did not sell well but it ended up being profitable because it was made into a movie, The Iron Curtain (1948).

According to John Sawatsky, the author of Gouzenko: The Untold Story (1984) Gouzenko fell-out with most of his guards. (18) He quoted one guard as saying: "Gouzenko was not a true lover of liberty. He was a thoroughly ignorant Russian peasant who had no connection with the Russian Intelligence Service except as a cipher clerk. I have known him for some time and feel he is an unsavory character." Gouzenko also came into conflict with George McClellan, the head of the RCMP Special Branch. When he threatened to withdraw protection he was accused of being a Soviet spy. (19)

The Fall of a Titan

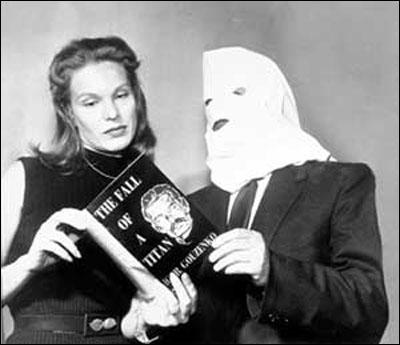

In January 1954 Gouzenko was interviewed by Drew Pearson on television. He wore a pillowcase over his head so that he could not be identified. Gouzenko also appeared in public, wearing a hood, to promote his novel, The Fall of a Titan (1954), about life in the Soviet Union under Joseph Stalin. The book was a huge success and was translated into more than forty languages. The Toronto Daily Star described it as a "panoramic novel... Tolstoyan in its sweep". (20)

Granville Hicks argued in the New York Times: "Involved as the story is, the reader never loses its thread, but goes on, always more and more absorbed, to the explosive climax.... It is Mr. Gouzenko's ability to create this atmosphere - the anguish of the masses, the ruthlessness of the privileged few, the universal terror - that gives his book its overwhelming plausibility." (21) Another critic described it as the work of a "young genius". The Fall of a Titan won the Governor-General of Canada's Prize for Literature in 1954.

Igor Gouzenko was interviewed by Tania Long of the New York Times in December 1954. He told Long that he wanted, above all, to be a good writer: "My immediate ambition you might say is to write my next book in half the time I took on my first. I think I have learned a lot, and what is most important is that I now have confidence in myself. Can you imagine how it was for four years, writing away day after day, with the feeling that maybe I was completely wrong and no one to encourage me?" (22) Gouzenko spent over twenty-five years on his next novel. According to his wife, he produced enough pages to fill three books. However, he never sent it to a publisher because he considered it unfinished. (23)

According to Amy W. Knight, the author of How the Cold War Began (2005): "In addition to acting as her husband's secretary, copyist, and chauffeur, Anna gave birth to eight children, made all their clothes, ran the household (or tried to), and engaged in several entrepreneurial ventures, none of which, including the purchase of the farm and some butcher shops, proved profitable." (24) In 1962, the Canadian government awarded the Gouzenkos a pension of five hundred dollars a month.

Gouzenko did not like being called a defector. It implied that he was a traitor. Instead, he insisted, he should be called an "escaper". When Newsweek referred to him as a defector in February 1964, he contacted a lawyer. He also disliked the suggestion in the article that defectors were psychologically troubled. Gouzenko refused to settle when the magazine offered him one thousand dollars in damages and he ended up getting nothing. However, he was successful in obtaining $750 from Mclean's Magazine. Another successful libel suit was against David Martin, the author of Wilderness of Mirrors. He objected to Martin questioning his motives for defecting. Gouzenko received $10,000 in damages. (25)

Roger Hollis

In 1972 Gouzenko was re interviewed by MI5. He later told the journalist, Chapman Pincher: "Stewart was stationed in Washington and asked to see me at the Royal York Hotel in Toronto. He read me a long report - several typed sheets - paragraph by paragraph. I was astonished to learn that this was the report submitted by the man, who could only have been Hollis, because I could not understand how he had written so much when he had asked me so little. I soon discovered why because the report was full of nonsense and lies. For instance, he reported me as telling him that I knew, in 1945, that there was a spy working for Britain in a high-level Government office in Moscow. I knew no such thing and had said nothing like that."

Gouzenko concluded that Roger Hollis must have been a Soviet spy: "As Stewart read the report to me it became clear that it had been faked to destroy my credibility so that my information about the spy in MI5 called 'Elli' could be ignored. If the report was written by Hollis then there is no doubt that he was a spy. I suspect that Hollis himself was 'Elli' and he may have feared that I might recognize him if I had seen a photograph of him in the files in Moscow but as a cypher-clerk I had no opportunity to see photographs." (26)

Igor Gouzenko developed diabetes and started to go blind and eventually he lost his sight completely. He then wrote on a braille typewriter or dictated the novel to Anna. He died at Mississauga on 25th June, 1982.

Primary Sources

(1) Igor Gouzenko, statement issued in Canada (10th October, 1945)

Having arrived in Canada two years ago, I was surprised during the first days by the complete freedom of the individual which exists in Canada but does not exists in Russia. The false representations about the democratic countries who are increasingly propagated in Russia were dissipated daily, as no lying propaganda can stand up against facts.

During two years of life in Canada, I saw the evidence of what a free people can do. What the Canadian people have accomplished and are accomplishing here under conditions of complete freedom- the Russian people, under the conditions of the Soviet regime of violence and suppression of all freedom, cannot accomplish even at the cost of tremendous sacrifices, blood and tears.

The last elections which took place recently in Canada especially surprised me. In comparison with them the system of elections in Russian appear as a mockery of the conception of free elections. For example, the fact that in elections in the Soviet Union one candidate is put forward, so that the possibilities of choice are eliminated, speaks for itself.

While creating a false picture of the conditions of life in these countries, the Soviet Government at the same time is taking all measures to prevent the peoples of democratic countries from knowing about the conditions of life in Russia. The facts about the brutal suppression of the freedom of speech, the mockery of the real religious feelings of the people, cannot penetrate into the democratic countries.

Having imposed its communist regime on the people, the Government of the Soviet Union asserts that the Russian people have, as it were, their own particularly understanding of freedom and democracy, different from that which prevails among the peoples of the western democracies. This is a lie. The Russian people same understanding of freedom as all the peoples of the world. However, the Russian people cannot realize their dream of freedom and a democratic government on account of cruel terror and persecution.

Holding forth at international conferences with voluble statements about peace and security, the Soviet Government is simultaneously preparing secretly for the third world war. To meet this war, these Soviet Government is creating in democratic countries, including Canada, a fifth column, in the organization of which even diplomatic representatives of the Soviet Government take part.

The announcement of the dissolution of the Comintern was, probably, the greatest farce of the Communists in recent years. Only the name was liquidated, with the object of reassuring public opinion in the democratic countries. Actually, the Comintern exists and continues its work, because the Soviet leaders have never relinquished the idea of establishing a Communist dictatorship throughout the world.

Taking account least of all that this adventurous idea will cost millions of Russian lives, the Communists are engendering hatred in Russian people towards everything foreign.

To many Soviet people here abroad, it is clear that the Communist Party in democratic countries have changed long ago from a political party into an agency net of the Soviet Government, into a fifth column in these countries to meet a war, into an instrument in the hands of the Soviet Government for creating artificial unrest, provocation, etc., etc.

Through numerous party agitators the Soviet Government stirs up the Russian people in every possible way against the peoples of the democratic countries, preparing the ground for the third world war.

During my residence in Canada I have seen how the Canadian people and their Government, sincerely wishing to help the Soviet people, sent supplies to the Soviet Union, collected money for the welfare of the Russian people, sacrificing the lives of their sons in the delivery of supplies across the ocean- and instead of gratitude for the help rendered, the Soviet Government is developing espionage activity in Canada, preparing to deliver a stab in the back of Canada- all this without the knowledge of the Russian people.

Convinced that such double-faced politics of the Soviet Government towards the democratic countries do not conform with the interests of the Russian people and endanger the security of civilization, I decided to break award from the Soviet regime and to announce my decision openly.

I am glad that I found the strength within myself to take this step and to warn Canada and the other democratic countries of the danger which hangs over them.

(2) Bill Macdonald, The True Intrepid: Sir William Stephenson and the Unknown Agents (2001)

There was a lot of false information floating around that disguised Gouzenko's whereabouts. On one occasion Bayly and his wife heard on the radio, as they were driving from Oshawa to Camp X, reports that Gouzenko was likely staying somewhere in the Laurentians, north of Montreal. "Everybody was heading there. And here's Gouzenko sitting on a deck chair outside the house, just as we drove up. I thought that was quite amusing. Poor old Gouzenko. He had no more brains than a peanut."

"How did he write that book then?"

"I think his wife did it. She was quite a girl. It was his wife who advised him what to do. The military attaché at the Soviet embassy got Gouzenko to decode one of his messages because he didn't feel like doing it himself. When Gouzenko decoded it he saw it was instructions for him to be sent back to the Soviet Union, because he wasn't trusted. "He'd be bumped off on landing," Bayly said, "the way the Russians were running things in those days." Bayly says Gouzenko then asked his wife for advice.

"What do I do now?" And so she told him, "Go into the vault and steal every secret thing you can put your hands on, and change the combination on the vault and lock the door. It'll take six weeks for the Russians to send somebody over to chisel the door of the safe open to find out you've taken all these things. Turn yourself over to the Canadians." So at the time the Canadian Prime Minister, King, said he wasn't going to be mixed up in that kind of Russian politics, and gave strict orders to the RCMP.

Norman Robertson, who was the Secretary of External Affairs, told this story to Bill, and what King was doing with this one. So Bill Stephenson headed up to Ottawa, borrowed my Buick from Camp X, and drove it up to Ottawa and arrested Gouzenko, military arrest, and said, "If you don't want to try him, we'll try him over in England. How would you like that?" King said, "No, I don't want that," so they gave this guy protection, and when he went back to his apartment, the Russians were just breaking into his apartment. They had finally got somebody over.

(3) Phillip Knightley, Philby: KGB Masterspy (1988)

Throughout the Sunday Times investigation in 1967 into the life and times of Kim Philby we were picking up tantalizing references to a Soviet defector at the end of the war who brought the first substantial clue to Philby's treachery and whose reception in the West left a permanent mark against Philby's name. Some former SIS or MI5 officer would drop into the conversation a remark like: "Of course, it was that defector in 1945 who put us on to Kim. After that you only had to look at the files to see it all." But when pressed for further details he would invariably clam up: "Better leave it at that, old boy. Don't want to get into trouble with the OSA (Official Secrets Act).

At first we thought these officers were referring to the defection in September 1945 of Igor Gouzenko, a twenty-five-year-old cypher clerk who had been based at the Soviet embassy in Ottawa from 1943 to 1945. Gouzenko sought asylum from the Canadian authorities who, unused to this sort of thing, considered handing him back to the Russians to avoid a diplomatic incident. It was only the intervention of Sir William Stephenson, a Canadian, head of British Security Coordination in New York during the war, who persuaded the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) to hide Gouzenko at a wartime special training school on the north shore of Lake Ontario, that saved him from being seized by his embassy colleagues.

Gouzenko was questioned, at first by RCMP officers, later by an SIS officer, Peter Dwyer, and then by Sir Roger Hollis, then head of MIS's section dealing with political parties in general and the British Communist Party in particular. I Gouzenko's value was that he had brought with him clues to the identity of Russian spies working in the West. Some of these clues he had obtained during his Ottawa posting, the others, he said, while doing routine duty in Moscow.

From Gouzenko's clues, the Canadian au4horities amassed evidence which led to the arrest and conviction in 1946 of Dr Alan Nunn May, the British scientist who had worked at Chalk River, Ontario, on the Allied atomic bomb project during the war, and who had passed information about his work to the Russians. In fact, Gouzenko brought so much material that the Canadian government set up a Royal Commission on espionage, and eventually eighteen people were prosecuted, nine of whom were convicted. One of these was Kathleen Willsher, who worked in the British High Commission's registry. She was arrested on 15 February 1946, pleaded guilty to passing secrets to the Russians and, since they were minor secrets, given only three years' imprisonment.

The clues that led to Willsher included Gouzenko's information that she worked in "administration" and that her code name was 'Elli'. But Gouzenko later claimed that he knew of yet another spy for the Russians who was also called 'Elli'. Unlike Wilsher, this second 'Elli' was of great importance. He said that he had learnt of the second 'Elli' when he was doing night duty in 1942 in the main military intelligence cypher room in Moscow. A colleague called Liubimov had passed him a telegram from this Soviet intelligence source in Britain. Pressed by his interrogators, Gouzenko offered a number of clues to the second 'Elli's' identity: he was a man, despite the female code name; he was in British counter-intelligence; he was so important he could be contacted only through messages left at prearranged hiding places; and, finally, he had 'something Russian in his background'. (This could mean, explained Gouzenko, no more than that he had visited the Soviet Union, had a wife with a Russian relative, or had a job to do with Russia.) Gouzenko said that Liubimov had told him that the second 'Elli's' information was so good. that when his telegrams came in, there was always a, woman present in the cypher room to read the decrypts and, if necessary, take them straight to Stalin.

If Gouzenko were to be believed, this meant that Moscow had a spy in Britain at the heart of Western intelligence (the CIA was not formed until 1,947), and a hunt began to identify- this second 'Elli'. The trouble was that Gouzenko kept changing his story. The exact place where 'Elli' worked was obviously very important. At first Gouzenko said that 'Elli' worked in 'five of MI', which could have been either MI5, or Section Five of MI6 (the other name for SIS) - Philby's section:. Later he was confident that 'Elli' worked in MI5, but then became less certain and accepted the possibility that he worked in counter-intelligence in SIS.

There were other, independent clues to Elli's identity. In 1944-5 the FBI had recorded radio messages sent from the Soviet consulate in New York. After the war its code-breakers started work to try to read these messages and in 1948 they began to get results. One message - to the Soviet embassy in London - advised that Gouzenko had . defected and asked that 'Stanley' be warned of this fact 'as soon as he returns to London'. MI5 interpreted this as meaning that a highly placed Russian intelligence officer was in danger of being exposed by Gouzenko and that he could not be warned at that moment because he was abroad and out of contact. But was 'Stanley' also 'Elli'; or were there two Russian agents in British intelligence; and if there were, why had the Russians wanted to warn only one, Stanley?

Over the years the possibilities were whittled down. When Maclean's defection in 1951 exposed him as a long-serving Soviet agent, it was realized that he could not be either 'Elli' or 'Stanley' - he was in Washington at the relevant time and in regular contact with his Soviet control. It could not have been Burgess because he was in London. It might just have been Blunt, who was abroad - at the relevant time. The file has never been closed and today, in the late 1980s, there are two schools of thought in Western intelligence.

The first, led by Peter Wright, the former M15 officer in exile in Australia, holds that 'Elli' was the late Sir Roger Hollis, director general of M15 from 1956 to 1965, and that Hollis was a Soviet penetration agent of status equal to, if not higher than, Philby. Although an investigation by a joint SIS-MI5 committee could not find any conclusive, evidence against Hollis and although a former secretary of the Cabinet, Lord Trend, reviewed this investigation and could find no substance in the allegations, this school defiantly sticks to its belief.

The second school, which includes at least three former heads of the services, rules out Hollis as 'Elli' and believes that 'Stanley' was almost certainly Philby, and that Philby could well have been 'Elli' too. He was abroad at the relevant time, on a mission in Istanbul (of which more later); he worked in 'five of MI', and he was certainly an important Soviet penetration agent. True, he did not have 'something Russian in his background' but Gouzenko was very vague about what this meant. Gouzenko in his old age (he died in 1982) said that he felt that Roger Hollis was 'Elli'; but in one of his last interviews before his death he said it was possible that Charles Ellis, an Australian-born SIS officer who had a Russian wife, was 'Elli'.

In the hope that Philby could end all this speculation and clear Hollis's name, it was one of the first subjects I raised with him in our conversations in Moscow. I began with a broad question: 'Can you cast any light on the Hollis affair?' Philby replied: 'I honestly cannot. Such a matter is not within my area of knowledge over here. All I can say is that I knew him, not well, but I did know him. And any idea that he was a Soviet penetration agent seems to me to be unlikely. I thought he was an upright if slightly stodgy Englishman.'

I believed Philby's reply for the simple reason that it would have been in the interests of the KGB to have encouraged the idea that Hollis was indeed a Soviet agent so as to create suspicion and uncertainty in the British services, to demean them in the eyes of the British public, to sow dissension between the British and American services, and to inflate the reputation of the Russians as brilliant spymasters. On the other hand, for Philby to have hinted to me that Hollis was a Soviet agent would automatically have been suspicious, so perhaps this was the only reply he could have made. Even if true, his answer did not take us much further, so I pressed him by saying: `You must know something about Gouzenko and the Elli business.'

Philby replied: 'Certainly. The first information about Gouzenko and Elli came from Stephenson. "C" called me in and asked me my opinion about it. I said Gouzenko's defection was obviously very important and we treated it as such. But it was a disaster for the KGB and there was no way I could help. The Mounties had Gouzenko so well protected that it was impossible for the Russians to do anything about him, bump him off or anything like that. So he was able to give away a big Canadian network, and the telegrams he brought with him when he defected would have been of great help to Western decrypters.'

(4) Igor Gouzenko, interviewed by Chapman Pincher, the author of Their Trade is Treachery (1981)

Stewart was stationed in Washington and asked to see me at the Royal York Hotel in Toronto. He read me a long report several typed sheets-paragraph by paragraph. I was astonished to learn that this was the report submitted by the man, who could only have been Hollis, because I could not understand how he had written so much when he had asked me so little.

I soon discovered why because the report was full of nonsense and lies. For instance, he reported me as telling him that I knew, in 1945, that there was a spy working for Britain in a high-level Government office in Moscow. I knew no such thing and had said nothing like that.

As Stewart read the report to me it became clear that it had been faked to destroy my credibility so that my information about the spy in M15 called 'Elli' could be ignored. If the report was written by Hollis then there is no doubt that he was a spy. I suspect that Hollis himself was 'Elli' and he may have feared that I might recognize him if I had seen a photograph of him in the files in Moscow but as a cypher-clerk I had no opportunity to see photographs.