British Security Coordination

Winston Churchill became prime minister in May 1940. Churchill realised straight away that it would be vitally important to enlist the United States as Britain's ally. Randolph Churchill, on the morning of 18th May, 1940, claims that his father told him "I think I see my way through.... I mean we can beat them." When Randolph asked him how, he replied with great intensity: "I shall drag the United States in."

Britain was in a very difficult situation. In 1939 Germany had a population of 80 million with a workforce of 41 million. Britain had a population of 46 million with less than half Germany's workforce. Germany's total income at market prices was £7,260 million compared to Britain's £5,242 million. More ominously, the Germans had spent five times what Britain had spent on armaments - £1,710 million versus £358 million. Churchill was informed that Britain would soon run out of money to fight the war.

Churchill sent William Stephenson to the United States to make certain arrangements on intelligence matters. Stephenson's main contact was Gene Tunney, a friend from the First World War, who had been World Heavyweight Champion (1926-1928) and was a close friend of J. Edgar Hoover, the head of the FBI. Tunney later recalled: "Quite to my surprise I received a confidential letter that was from Billy Stephenson, and he asked me to try and arrange for him to see J. Edgar Hoover... I found out that his mission was so important that the Ambassador from England could not be in on it, and no one in official government... It was my understanding that the thing went off extremely well." Stephenson was also a friend of Ernest Cuneo. He worked for President Franklin D. Roosevelt and according to Stephenson was the leader of "Franklin's brain trust". Cuneo met with Roosevelt and reported back that the president wanted "the closest possible marriage between the FBI and British Intelligence."

On his return to London, Stephenson reported back to Churchill. After hearing what he had to say, Churchill told Stephenson: "You know what you must do at once. We have discussed it most fully, and there is a complete fusion of minds between us. You are to be my personal representative in the United States. I will ensure that you have the full support of all the resources at my command. I know that you will have success, and the good Lord will guide your efforts as He will ours." Charles Howard Ellis said that he selected Stephenson because: "Firstly, he was Canadian. Secondly, he had very good American connections... he had a sort of fox terrier character, and if he undertook something, he would carry it through."

William Stephenson establishes the British Security Coordination

Churchill now instructed Stewart Menzies, head of MI6, to appoint William Stephenson as the head of the British Security Coordination (BSC). Menzies told Gladwyn Jebb on 3rd June, 1940: "I have appointed Mr W.S. Stephenson to take charge of my organisation in the USA and Mexico. As I have explained to you, he has a good contact with an official (J. Edgar Hoover) who sees the President daily. I believe this may prove of great value to the Foreign Office in the future outside and beyond the matters on which that official will give assistance to Stephenson. Stephenson leaves this week. Officially he will go as Principal Passport Control Officer for the USA."

As William Boyd has pointed out: "The phrase (British Security Coordination) is bland, almost defiantly ordinary, depicting perhaps some sub-committee of a minor department in a lowly Whitehall ministry. In fact BSC, as it was generally known, represented one of the largest covert operations in British spying history... With the US alongside Britain, Hitler would be defeated - eventually. Without the US (Russia was neutral at the time), the future looked unbearably bleak... polls in the US still showed that 80% of Americans were against joining the war in Europe. Anglophobia was widespread and the US Congress was violently opposed to any form of intervention." An office was opened in the Rockefeller Centre in Manhattan with the agreement of President Franklin D. Roosevelt and J. Edgar Hoover of the FBI.

Thomas E. Mahl, the author of Desperate Deception: British Covert Operations in the United States: 1939-44 (1998), has argued that Ernest Cuneo was "liaison between British Security Coordination and several departments of the U.S. government". He later wrote to Charles Howard Ellis, assistant-director of the British Security Coordination: "I saw Adolf Berle at State Department, Eddie Tamm, J. Edgar Hoover and more often the Attorney General; on various other matters Dave Niles and the White House and Ed Foley at the Treasury, but as far as I know there wasn't a sentence recorded. I reported to Bill Donovan and George Bowden, but never in writing."

Winston Churchill had a serious problem. Joseph P. Kennedy was the United States Ambassador to Britain. He soon came to the conclusion that the island was a lost cause and he considered aid to Britain fruitless. Kennedy, an isolationist, consistently warned Roosevelt "against holding the bag in a war in which the Allies expect to be beaten." Neville Chamberlain wrote in his diary in July 1940: "Saw Joe Kennedy who says everyone in the USA thinks we shall be beaten before the end of the month." Averell Harriman later explained the thinking of Kennedy and other isolationists: "After World War I, there was a surge of isolationism, a feeling there was no reason for getting involved in another war... We made a mistake and there were a lot of debts owed by European countries. The country went isolationist.

In July, 1940, Henry Luce, C. D. Jackson, Freda Kirchwey, Raymond Gram Swing, Robert Sherwood, John Gunther and Leonard Lyons, Ernest Angell and Carl Joachim Friedrich established the Council for Democracy in July, 1940. According to Kai Bird the organization "became an effective and highly visible counterweight to the isolation rhetoric" to America First Committee led by Charles Lindbergh and Robert E. Wood: "With financial support from Douglas and Luce, Jackson, a consummate propagandist, soon had a media operation going which was placing anti-Hitler editorials and articles in eleven hundred newspapers a week around the country." The isolationist Chicago Tribune accused the Council for Democracy of being under the control of foreigners: "The sponsors of the so-called Council for Democracy... are attempting to force this country into a military adventure on the side of England."

According to The Secret History of British Intelligence in the Americas, 1940-45, a secret report written by leading operatives of the British Security Coordination (Roald Dahl, H. Montgomery Hyde, Giles Playfair, Gilbert Highet and Tom Hill), William Stephenson played an important role in the formation of the Council for Democracy: "William Stephenson decided to take action on his own initiative. He instructed the recently created SOE Division to declare a covert war against the mass of American groups which were organized throughout the country to spread isolationism and anti-British feeling. In the BSC office plans were drawn up and agents were instructed to put them into effect. It was agreed to seek out all existing pro-British interventionist organizations, to subsidize them where necessary and to assist them in every way possible. It was counter-propaganda in the strictest sense of the word. After many rapid conferences the agents went out into the field and began their work. Soon they were taking part in the activities of a great number of interventionist organizations, and were giving to many of them which had begun to flag and to lose interest in their purpose, new vitality and a new lease of life. The following is a list of some of the larger ones... The League of Human Rights, Freedom and Democracy... The American Labor Committee to Aid British Labor... The Ring of Freedom, an association led by the publicist Dorothy Thompson, the Council for Democracy; the American Defenders of Freedom, and other such societies were formed and supported to hold anti-isolationist meetings which branded all isolationists as Nazi-lovers."

William Stephenson knew that with leading officials supporting isolationism he had to overcome these barriers. His main ally in this was another friend, William Donovan, who he had met in the First World War. "The procurement of certain supplies for Britain was high on my priority list and it was the burning urgency of this requirement that made me instinctively concentrate on the single individual who could help me. I turned to Bill Donovan." Donovan arranged meetings with Henry Stimson (Secretary of War), Cordell Hull (Secretary of State) and Frank Knox (Secretary of the Navy). The main topic was Britain's lack of destroyers and the possibility of finding a formula for transfer of fifty "over-age" destroyers to the Royal Navy without a legal breach of U.S. neutrality legislation. Lord Lothian, the British ambassador in Washington, informed Knox on 28th July, 1940, that Britain had entered the war with 176 destroyers and that only 70 of these were still afloat. He requested 40 to 100 destroyers and 100 flying boats.

(If you find this article useful, please feel free to share. You can follow John Simkin on Twitter, Google+ & Facebook or subscribe to our monthly newsletter)

It was decided to send William Donovan to Britain on a fact-finding mission. He left on 14th July, 1940 with the journalist Edgar Ansel Mowrer.When he heard the news, Joseph P. Kennedy complained: "Our staff, I think is getting all the information that possibility can be gathered, and to send a new man here at this time is to me the height of nonsense and a definite blow to good organization." He added that the trip would "simply result in causing confusion and misunderstanding on the part of the British". Andrew Lycett has argued: "Nothing was held back from the big American. British planners had decided to take him completely into their confidence and share their most prized military secrets in the hope that he would return home even more convinced of their resourcefulness and determination to win the war."

William Donovan arrived back in the United States in early August, 1940. In his report to President Franklin D. Roosevelt he argued: "(1) That the British would fight to the last ditch. (2) They could not hope to hold to hold the last ditch unless they got supplies at least from America. (3) That supplies were of no avail unless they were delivered to the fighting front - in short, that protecting the lines of communication was a sine qua non. (4) That Fifth Column activity was an important factor." Donovan also urged that the government should sack Ambassador Joseph Kennedy, who was predicting a German victory. Edgar Ansel Mowrer also wrote a series of articles, based on information supplied by William Stephenson, that Nazi Germany posed a serious threat to the United States.

On 22nd August, 1940, Stephenson reported to London that the destroyer deal was agreed upon. The agreement for transferring 50 aging American destroyers, in return for the rights to air and naval basis in Bermuda, Newfoundland, the Caribbean and British Guiana, was announced 3rd September, 1940. The bases were leased for 99 years and the destroyers were of great value as convey escorts. Lord Louis Mountbatten, the British Chief of Combined Operations, commented: "We were told that the man primarily responsible for the loan of the 50 American destroyers to the Royal Navy at a critical moment was Bill Stephenson; that he had managed to persuade the president that this was in the ultimate interests of America themselves and various other loans of that sort were arranged. These destroyers were very important to us...although they were only old destroyers, the main thing was to have combat ships that could actually guard against and attack U-boats."

American First Committee

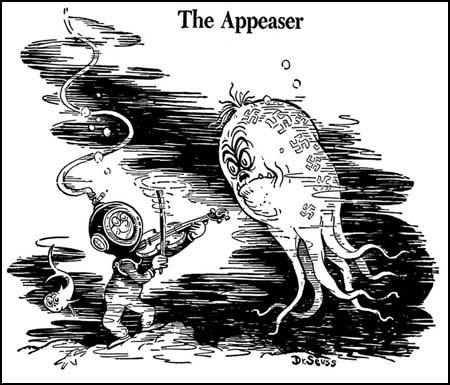

Stephenson was very concerned with the growth of the American First Committee. by the spring of 1941, the British Security Coordination estimated that there were 700 chapters and nearly a million members of isolationist groups. Leading isolationists were monitored, targeted and harassed. When Gerald Nye spoke in Boston in September 1941, thousands of handbills were handed out attacking him as an appeaser and Nazi lover. Following a speech by Hamilton Fish, a member of a group set-up by the BSC, the Fight for Freedom, delivered him a card which said, "Der Fuhrer thanks you for your loyalty" and photographs were taken.

A BSC agent approached Donald Chase Downes and told him that he was working under the direct orders of Winston Churchill. "Our primary directive from Churchill is that American participation in the war is the most important single objective for Britain. It is the only way, he feels, to victory over Nazism." Downes agreed to work for the BSC in spying on the American First Committee. He was also instructed to find information on German consulates in Boston and Cleveland and the Italian consulate in the capital. He later recalled in his autobiography, The Scarlett Thread (1953) that he received assistance in his work from the Jewish Anti-Defamation League, Congress for Industrial Organisation and U.S. army counter-intelligence. Bill Macdonald, the author of The True Intrepid: Sir William Stephenson and the Unknown Agents (2001), has pointed out: "Downes eventually discovered there was Nazi activity in New York, Washington, Chicago, San Francisco, Cleveland and Boston. In some cases they traced actual transfers of money from the Nazis to the America Firsters."

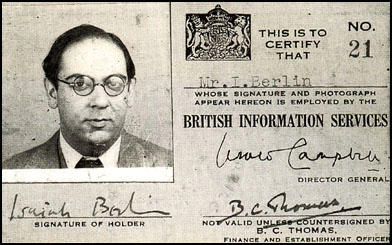

Charles Howard Ellis was sent to New York City to work alongside William Stephenson as assistant-director. Together they recruited several businessmen, journalists, academics and writers into the British Security Coordination. This included Roald Dahl, H. Montgomery Hyde, Ian Fleming, Cedric Belfrage, Ivar Bryce, David Ogilvy, Isaiah Berlin, Eric Maschwitz, Giles Playfair, Benn Levy, Noël Coward and Gilbert Highet.

Maschwitz admitted in his autobiography, No Chip on My Shoulder (1957) "I had been provided with a passport that gave my profession as Ministry of Supply. I was to be taken not as an army officer but as a former playwright on national service as a civilian." Grace Garner, Stephenson's secretary, claimed he recruited several journalists including Sydney Morrell from the Daily Express and Doris Sheridan, from the Daily Mirror. "This was propaganda, or at least putting forward the British case. Sheridan liaised with the Arab sections in New York, keeping in touch with foreign nationals. The English playwright Eric Maschwitz was recruited to write propaganda and scripts. University professor Bill Deaken worked for the office, as well as the philosopher A. J. Ayer." John D. Bernal, who was working closely with Winston Churchill during the war, used to call in the office. Garner described as a "dead ringer" for Harpo Marx. "You could have walked him straight onto the set. Wild. He had a funny hat on, and this saggy, greeny old coat, bulging with documents."

An office was opened in the Rockefeller Centre in Manhattan with the agreement of President Franklin D. Roosevelt and J. Edgar Hoover of the FBI. Roosevelt's top security advisor, Adolph Berle, sent a message to Sumner Welles, the Under Secretary of State: "The head of the field service appears to be Mr. William S. Stephenson... in charge of providing protection for British ships, supplies etc. But in fact a full size secret police and intelligence service is rapidly evolving... with district officers at Boston, New York City, Philadelphia, Baltimore, Charleston, New Orleans, Houston, San Francisco, Portland and probably Seattle.... I have in mind, of course, that should anything go wrong at any time, the State Department would be called upon to explain why it permitted violation of American laws and was compliant about an obvious breach of diplomatic obligation... Were this to occur and a Senate investigation should follow, we should be on very dubious ground if we have not taken appropriate steps."

BSC and the American Media

Cedric Belfrage joined the BSC in December 1941. William Deaken, one of the senior figures in the organisation, argued: "Belfrage was brought in as one of the propaganda people... he was a known communist." He was recruited by the BSC because if his contacts with American journalists. The strategy was to work with American journalists to persuade them to write articles that would advocate intervention in the Second World War.

According to William Boyd: "BSC's media reach was extensive: it included such eminent American columnists as Walter Winchell and Drew Pearson, and influenced coverage in newspapers such as the Herald Tribune, the New York Post and the Baltimore Sun. BSC effectively ran its own radio station, WRUL, and a press agency, the Overseas News Agency (ONA), feeding stories to the media as they required from foreign datelines to disguise their provenance. WRUL would broadcast a story from ONA and it thus became a US "source" suitable for further dissemination, even though it had arrived there via BSC agents. It would then be legitimately picked up by other radio stations and newspapers, and relayed to listeners and readers as fact. The story would spread exponentially and nobody suspected this was all emanating from three floors of the Rockefeller Centre. BSC took enormous pains to ensure its propaganda was circulated and consumed as bona fide news reporting. To this degree its operations were 100% successful: they were never rumbled."

Roald Dahl was assigned to work with Drew Pearson, one of America's most influential journalist as the time. "Dahl described his main function with BSC as that of trying to 'oil the wheels' that often ground imperfectly between the British and American war efforts. Much of this involved dealing with journalists, something at which he was already skilled. His chief contact was the mustachioed political gossip columnist Drew Pearson, whose column, Washington Merry-Go-Round, was widely regarded as the most important of its kind in the United States."

Ian Fleming, Louis Mountbatten and James Roosevelt were visitors to the British Security Coordination head office. Grace Garner recalls: "Mountbatten would not come to the office frequently. Fleming came in from time to time, and of course they were both so good-looking that just like dominoes, the girls would go down - whoosh, like that.... James Roosevelt, the president's son, did a few things in the way of propaganda for Britain, and he appeared at meetings."

William Allen White had established the Committee to Defend America by Aiding the Allies (CDAAA) in May, 1940. White gave an interview to the Chicago Daily News where he argued: "Here is a life and death struggle for every principle we cherish in America: For freedom of speech, of religion, of the ballot and of every freedom that upholds the dignity of the human spirit... Here all the rights that common man has fought for during a thousand years are menaced... The time has come when we must throw into the scales the entire moral and economic weight of the United States on the side of the free peoples of Western Europe who are fighting the battle for a civilized way of life." It was not long before White's organization had 300 chapters nationwide.

Members of the CDAAA argued that by advocating American military materiel support of Britain was the best way to keep the United States out of the war in Europe. It played an important role in the passing of the Lend-Lease Act on 11th March, 1941. The legislation gave President Franklin D. Roosevelt the powers to sell, transfer, exchange, lend equipment to any country to help it defend itself against the Axis powers. A sum of $50 billion was appropriated by Congress for Lend-Lease. The money went to 38 different countries with Britain receiving over $31 billion.

However, the CDAAA refused to support military intervention in the war. William Stephenson as the head of the British Security Coordination (BSC), found this frustrating and he encouraged William Donovan to recruit Americans to start a much more militant organisation. Donovan approached Allen W. Dulles and along with BSC agent, Sydney Morrell, to establish the Fight for Freedom (FFF) group in April 1941.

In July 1941 Sydney Morrell was asked to write a report on the organisations that had been set up with the help of the BSC. "The Non-Sectarian Anti-Nazi League. Used for the vehement exposure of enemy agents and isolationists. Prints a wide variety of pamphlets, copies of which have been sent to you. Has recently begun to attack Lindbergh and the many other conscious or unconscious native Fascists.... Friends of Democacy. An example of the work of this organization is attached. It is a complete attack upon Henry Ford for his Nazi leanings." Morrell believed that more could be achieved if they created one unified organization: "The most effective of all propaganda towards the US would be through a unified organization which could be used to attack the isolationists, such as America First, on the other hand, and to create a Nation-wide campaign for an American declaration of war upon the other."

Members included Ulric Bell, (Executive Chairman), Peter Cusick (Executive Secretary), Allen W. Dulles, Joseph Alsop, Henry Luce, Dean G. Acheson, James P. Warburg, Marshall Field III, Fiorello LaGuardia, Lewis William Douglas, Carter Glass, Harold K. Guinzburg, Conyers Read, Spyros Skouras and Henry P. Van Dusen. The group also contained several journalists such as Herbert Agar (Louisville Courier-Journal), Geoffrey Parsons (New York Herald Tribune), Ralph Ingersoll (Picture Magazine) and Elmer Davis (CBS). At its peak, the FFF headquarters at 1270 Sixth Avenue in New York City had an office staff of twenty-five.

Fight for Freedom group monitored the activities of the leading isolationist organization, the America First Committee. Leading isolationists were also targeted and harassed. When Gerald Nye spoke in Boston in September 1941, thousands of handbills were handed out attacking him as an appeaser and Nazi lover. Following a speech by Hamilton Stuyvesan Fish, a member of a group set-up by the BSC, the Fight for Freedom, delivered him a card which said, "Der Fuhrer thanks you for your loyalty" and photographs were taken.

In October 1941, the British Security Coordination attempted to disrupt a rally at Madison Square Garden by issuing counterfeit tickets. H. Montgomery Hyde has argued that the plan backfired as the AFC got a lot of publicity from the meeting with 20,000 people inside and the same number supporting the cause outside. The only opposition was an obvious agent provocateur shouting "Hang Roosevelt".

In 1941 BSC agent Donald MacLaren employed Rex Stout, George Merton (another BSC agent) and Sylvia Porter of the New York Post, to write a propaganda booklet entitled Sequel to the Apocalypse: The Uncensored Story: How Your Dimes and Quarters Helped Pay for Hitler's War. It was published in 1942. Stout also hosted three weekly radio shows, and coordinated the volunteer services of American writers to help the war effort.

BSC and Public Opinion Polls

Another BSC agent, Sanford Griffith, established a company Market Analysts Incorporated and was initially commissioned to carry out polls for the anti-isolationist Committee to Defend America by Aiding the Allies and Fight for Freedom group. Griffith's assistant, Francis Adams Henson, a long time activist against the Nazi Germany government, later recalled: "My job was to use the results of our polls, taken among their constituents, to convince on-the-fence Congressmen and Senators that they should favor more aid to Britain."

As Richard W. Steele has pointed out: "public opinion polls had become a political weapon that could be used to inform the views of the doubtful, weaken the commitment of opponents, and strengthen the conviction of supporters." William Stephenson later admitted: "Great care was taken beforehand to make certain the poll results would turn out as desired. The questions were to steer opinion toward the support of Britain and the war... Public Opinion was manipulated through what seemed an objective poll."

Michael Wheeler, the author of Lies, Damn Lies, and Statistics: The Manipulation of Public Opinion in America (2007): "Proving that a given poll is rigged is difficult because there are so many subtle ways to fake data... a clever pollster can just as easily favor one candidate or the other by making less conspicuous adjustments, such as allocating the undecided voters as suits his needs, throwing out certain interviews on the grounds that they were non-voters, or manipulating the sequence and context within which the questions are asked... Polls can even be rigged without the pollster knowing it.... Most major polling organizations keep their sampling lists under lock and key."

The main target of these polls concerned the political views of leading politicians opposed to Lend-Lease. This included Hamilton Stuyvesan Fish. In February 1941, a poll of Fish's constituents said that 70 percent of them favored the passage of Lend-Lease. James H. Causey, president of the Foundation for the Advancement of Social Sciences, was highly suspicious of this poll and called for a congressional investigation.

Ernest Cuneo was such an important figure to the British Security Coordination that he was given his own code name, "Crusader". He later admitted that he passed important information obtained from his government position to the BSC: "Friendly and neutral powers are quaint and laughable terms unrecognised in the world of international intelligence. Every major nation taps every other major nation, none more than its Allies."

Jennet Conant, the author of The Irregulars: Roald Dahl and the British Spy Ring in Wartime Washington (2008) argues that Cuneo was "empowered to feed select British intelligence items about Nazi sympathizers and subversives" to friendly journalists such as Walter Winchell, Drew Pearson, Walter Lippmann, William Allen White, Dorothy Thompson, Raymond Gram Swing, Edward Murrow, Vincent Sheean, Helen Kirkpatrick, Eric Sevareid, Edmond Taylor, Rex Stout, Edgar Ansel Mowrer and Whitelaw Reid, who "were stealth operatives in their campaign against Britain's enemies in America".

Cuneo also worked closely with editors and publishers who were supporters of American intervention into the Second World War. This included Arthur Hays Sulzberger (New York Times), Henry Luce (Time Magazine and Life Magazine), Helen Rogers Reid (New York Herald Tribune), Barry Bingham (Louisville Courier-Journal), Paul C. Patterson (Baltimore Sun), Dorothy Schiff (New York Post) and Ralph Ingersoll (Picture Magazine).

Marshall Field III was a strong supporter of the Allies in the Second World War. He worked closely with the administration of President Franklin D. Roosevelt and Fight for Freedom, an organization established by the British Security Coordination. In October 1941 Field started the Chicago Sun to counter the isolationist policy of Colonel Robert McCormick, who owned the Chicago Tribune. According to Field's editor, Turner Catledge: "It was early in 1941 that Field resolved to start a newspaper... Roosevelt was trying to move the nation toward support of England and Colonel McCormick was fighting him tooth and nail... The Tribune's influence on the American heartland was great, and to Field and others who thought the United States must fight Nazism, McCormick's daily tirades were agonizing."

Walter Trohan argues in his autobiography, Political Animals: Memoirs of a Sentimental Cynic (1975), that J. Edgar Hoover and the FBI became involved in this project: "In order to help the paper get an Associated Press franchise, then a guarded possession, FDR had FBI agents call upon various small-town publishers and urge them to support Field's bid for a franchise. J. Edgar Hoover, head of the FBI, later showed me the order he had received to undertake a campaign, which he considered above and beyond his unit's functions."

Picture Magazine managed to achieve a circulation of 200,000, however, without the ability to carry advertising, it could only survive with the sponsorship of Marshall Field III, who now owned Chicago Sun, another pro-intervention newspaper. Thomas E. Mahl, the author of Desperate Deception: British Covert Operations in the United States, 1939-44 (1998) has argued: "PM never attracted enough circulation to make money, but it was a wonderful propaganda vehicle despite its small circulation. In September, 1940, Field bought out the other backers for twenty cents on the dollar." In a declassified report from British Security Coordination it listed PM as "among those who rendered service of particular value".

Released BSC documents list Walter Lippmann as "among those who rendered service of particular value". Thomas E. Mahl, the author of Desperate Deception: British Covert Operations in the United States, 1939-44 (1998) has argued: "In late winter or early spring 1940, Lippmann even told the British to initiate Secret Intelligence Service operations against American isolationists. His exact thoughts are unknown. His specific ideas were 'too delicate' for the British Foreign Office to put to paper, but the idea is quite clear. Lippmann was a heavy weight. His suggestions on how to handle the American public reached as high as the British War Cabinet."

In some cases journalists complained about the change of policy. H. L. Mencken , who was a regular contributor as well as being on the board of the Baltimore Sun, resigned in 1941 because of what he considered to be the newspaper's "wildly pro-British bias". He later recalled a meeting he had with the publisher, Paul C. Patterson: "I told Patterson that, in my judgment, the English had found him an easy mark, and made a monkey out of him. He did not attempt to dispute the main fact." Mencken wrote in his diary in October 1945: "From the first to the last they (the newspapers owned by Patterson) were official organs and nothing more, and taking one day with another they were official organs of England rather than of the United States."

Robert E. Sherwood, one of Roosevelt's speechwriters, also agreed to help the British Security Coordination. As he pointed out in his book, Roosevelt and Hopkins: An Intimate History (1948): "Six months before the United States entered the war... there was, by Roosevelt's order and despite State Department qualms, effectively close cooperation between J. Edgar Hoover and the FBI and British security services under the direction of the quiet Canadian, William Stephenson... If the isolationists had known the full extent of the secret alliance between the U.S. and Britain, their demands for the President's impeachment would have rumbled like thunder across the land." William Stephenson later claimed that Sherwood was "one of the most persistent and effective" of those contacts with "influence at the White House".

Isaiah Berlin, one of Britain's leading philosophers, was also recruited to work for the BSC. Michael Ignatieff, the author of A Life of Isaiah Berlin (1998) has pointed out: "Isaiah Berlin's job was to get America into the war. He was to be a propagandist, working with trade unions, black organizations and Jewish groups. He lived in mid-town Manhattan hotels and went to work every morning at the British Information Services on the forty-fourth floor of a building in the Rockefeller Center. There he went through piles of American press clippings ranged in shoe-boxes. From these he put together a weekly report for the Ministry of Information on the state of American public opinion. In the early months of 1941 the isolations were in the ascendant and the prospects of getting America into the war seemed remote." Despite his efforts, by the end of 1941, 80% of the American public was still opposed to the sending of American troops to Europe.

Ernest Cuneo later admitted that the BSC sometimes committed illegal acts: "Given the time, the situation, and the mood, it is not surprising however, that BSC also went beyond the legal, the ethical, and the proper. Throughout the neutral Americas, and especially in the U.S., it ran espionage agents, tampered with the mails, tapped telephone, smuggled propaganda into the country, disrupted public gatherings, covertly subsidized newspapers, radios, and organizations, perpetrated forgeries - even palming one off on the President of the United States - violated the aliens registration act, shanghaied sailors numerous times, and possibly murdered one or more persons in this country."

In an interview with Thomas E. Mahl, for his book, Desperate Deception: British Covert Operations in the United States, 1939-44 (1998), Edmond Taylor, admitted the role played by the British Security Coordination in his journalism: "What they did more often, especially before Pearl Harbor and in the early months of the war, was to connive, usually is non-committally as possible, with Americans like myself who were willing to go out of regular (or even legal) channels to try to bend U.S. policy towards objectives that the British, as well as the Americans in question, considered desirable."

Isaiah Berlin visited editors and tried to persuade them to publish articles that provided a positive image of Britain. Berlin took Harold Ross, the editor of the New Yorker, to lunch at the Algonquin Hotel. At the end of the lunch Ross commented: "Young man, I can't understand a word you say, but if you write anything, I'll print it." Berlin also worked closely with Jewish supporters of American intervention in the Second World War. This included Rabbi Stephen Wise and Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandelis. Other contacts included Sidney Hillman and David Dubinsky, the leaders of the Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America (ACWA).

Arthur Hays Sulzberger supported a series of pro-intervention groups established by the British Security Coordination. In his book, Without Fear or Favor: The New York Times and its Times (1980) Harrison Salisbury argues, "Not long after the outbreak of the war (in Europe) Sulzberger learned that a number of these correspondents had connections with MI6 the British intelligence agency." Salisbury describes him as being "very angry" about this but they remained on the newspaper. According to Hanson W. Baldwin, a journalist on the New York Times "leaks to British intelligence through The Times continued after U.S. entry into the war."

Despite the help he gave to the campaign to persuade the United States to enter the Second World War, Sulzberger was still criticised by the BSC for not supporting the cause as well as the New York Herald Tribune. One of its agents, Valentine Williams had a meeting with Sulzberger and on 15th September, 1941, he reported to Hugh Dalton, Minister of Economic Warfare: "I had an hour with Arthur Sulzberger, proprietor of the New York Times, last week. He told me that for the first time in his life he regretted being a Jew because, with the tide of anti-semitism rising, he was unable to champion the anti-Hitler policy of the administration as vigorously and as universally as he would like as his sponsorship would be attributed to Jewish influence by isolationists and thus lose something of its force." He also suggested to Isaiah Berlin, who lobbied Sulzberger to be more outspoken about the treatment of Jews in Nazi Germany: "Mr Berlin, don't you believe that if the word Jew was banned from the public press for fifty years, it would have a strongly positive influence."

Benjamin de Forest Bayly was brought in as Deputy Director of Communication. He later recalled that they wanted "a man who understood something about commercial communications, and who would have enough security clearance to buy top secret radio material. The point is that the English were, at the moment, developing all sorts of secret radio. Putting in the spies in Europe, and that sort of thing. They didn't want to divulge what they were buying through normal commercial channels."

Bill Ross Smith, who worked for British Security Coordination in New York City, has argued: "Stephenson was exactly the right man, because he had all these terrific contacts and had this tremendous flair of influencing people, in an incredibly quiet way. If he could walk into this room now, he could sit down in that chair and, without saying a word, dominate this room. I tell you he was absolutely, bloody well a genius... He was no James Bond because he didn't go around killing people with his bare hands, or even with a gun. He dealt strictly with his brain and personality."

Over the next few years Stephenson worked closely with William Donovan, the chief of the Office of Strategic Service (OSS). Gill Bennett has argued: "Each is a figure about whom much myth has been woven, by themselves and others, and the full extent of their activities and contacts retains an element of mystery. Both were influential: Stephenson as head of British Security Coordination (BSC), the organisation he created in New York at Menzies's request and Donovan, working with Stephenson as intermediary between Roosevelt and Churchill, persuading the former to supply clandestine military supplies to the UK before the USA entered the war, and from June 1941 head of the COI and thus one of the architects of the US Intelligence establishment."

Benjamin de Forest Bayly has argued that Stephenson was very close to Henry Luce, Walter Winchell and Robert E. Sherwood: "He liked propaganda. And propaganda was really one of the important things he did. He saw to it, before even Pearl Harbor, that the anti-British feeling there was squelched by writers. He got all sorts of people to write things that helped that... Winchell was a man who actually got a reputation for being a very straightforward person, and he did a lot of propaganda work for Bill Stephenson. If Bill could sell him on why the U.S. should do this, and if it did that, then Winchell would be your man."

Isaiah Berlin had regular meetings with journalists such as Drew Pearson, Walter Lippman, Philip Graham, Joseph Alsop, Arthur Krock and Marquis Childs, in an effort to publish information favourable to the British. Berlin took Harold Ross, the editor of the New Yorker, to lunch at the Algonquin Hotel. At the end of the lunch Ross commented: "Young man, I can't understand a word you say, but if you write anything, I'll print it." Despite his efforts, by the end of 1941, 80% of the American public was still opposed to the sending of American troops to Europe.

One of Stephenson's agents was Ivar Bryce. According to Thomas E. Mahl, the author of Desperate Deception: British Covert Operations in the United States, 1939-44 (1998): "Bryce worked in the Latin American affairs section of the BSC, which was run by Dickie Coit (known in the office as Coitis Interruptus). Because there was little evidence of the German plot to take over Latin America, Ivar found it difficult to excite Americans about the threat."

Nicholas J. Cull, the author of Selling War: The British Propaganda Campaign Against American Neutrality (1996), has argued: "During the summer of 1941, he (Bryce) became eager to awaken the United States to the Nazi threat in South America." It was especially important for the British Security Coordination to undermine the propaganda of the American First Committee. Bryce recalls in his autobiography, You Only Live Once (1975): "Sketching out trial maps of the possible changes, on my blotter, I came up with one showing the probable reallocation of territories that would appeal to Berlin. It was very convincing: the more I studied it the more sense it made... were a genuine German map of this kind to be discovered and publicised among... the American Firsters, what a commotion would be caused."

William Stephenson, who once argued that "nothing deceives like a document", approved the idea and the project was handed over to Station M, the phony document factory in Toronto run by Eric Maschwitz, of the Special Operations Executive (SOE). It took them only 48 hours to produce "a map, slightly travel-stained with use, but on which the Reich's chief map makers... would be prepared to swear was made by them." Stephenson now arranged for the FBI to find the map during a raid on a German safe-house on the south coast of Cuba. J. Edgar Hoover handed the map over to William Donovan. His executive assistant, James R. Murphy, delivered the map to President Franklin D. Roosevelt. On 27th October, 1941: "I have in my possession a secret map, made in Germany by Hitler's government, by planners of the new world order. It is a map of South America and part of Central America as Hitler proposes to organize it."

The historian, Thomas E. Mahl argues that "as a result of this document Congress dismantled the last of the neutrality legislation." Nicholas J. Cull has suggested that Roosevelt should not have realised it was a forgery. He points out that Adolf Berle , the Assistant Secretary of State for Latin American Affairs, had already warned Cordell Hull, the Secretary of State that "British intelligence has been very active in making things appear dangerous in South America. We have to be a little on our guard against false scares."

British Security Coordination (BSC) managed to record the conversations of Japanese special envoy Suburu Kurusu with others in the Japanese consulate in November 1941. Marion de Chastelain was the cipher clerk who transcribed these conversations. On 27th November, 1941, William Stephenson sent a telegram to the British government: "Japanese negotiations off. Expect action within two weeks." According to Roald Dahl, who worked for BSC: "Stephenson had tapes of them discussing the actual date of Pearl Harbor... and he swears that he gave the transcription to FDR. He swears that they knew therefore of the oncoming attack on Pearl Harbor and hadn't done anything about it."

Bill Macdonald, the author of The True Intrepid: Sir William Stephenson and the Unknown Agents (2001) has pointed out: "Although they were called British Security Coordination, the Stephenson people were very much a law unto themselves. They made many separate deals with other countries and distributed information amongst the three Western Allies. They controlled many of the secrets of the three countries, including ULTRA and MAGIC, and also had communication influence in the South Pacific and Asia. There were a number of British appointments at BSC, but essentially, Stephenson contacted his friends, put them to work, and had them find staff... The important work these people accomplished during the war has never been fully explored."

A. J. Ayer, joined the British Security Coordination in October 1941. In his autobiography, Part of My Life (1977), Ayer points out: "The New York offices of SOE were in Rockefeller Center. It shared them with other Intelligence agencies under the general title of British Security Co-ordination.... My first duty was to learn as much as I could about South American politics and the persons and organizations in the various countries who were likely to be German or Italian sympathizers. At the beginning, therefore, my time was mostly spent in mastering the contents of a very large number of files. The countries about which I came to know most were Argentina, Chile, Uruguay and Peru."

Pearl Harbor

After the bombing of Pearl Harbor in December 1941, much of the BSC's security and intelligence work could legitimately be taken over the FBI and other United States agencies. William Stephenson told Stewart Menzies, head of MI6, that the very existence of the BSC was now threatened. In January 1942, the McKellar Bill was before Congress, requiring the registration of all "foreign agents". Stephenson told Menzies this "might render work of this office in U.S.A. impossible as it is obviously inadmissible that all our records and other material should be made public". After some vigorous lobbying by Stephenson and others, the McKellar Bill was amended so that agents of the Allied "United Nations" would be exempt from registration and need only report in private to their own embassy.

On 13th February, 1942, Adolf Berle received information from the FBI that a BSC agent, Dennis Paine, had been investigating him in order to "get the dirt" on him. Paine was expelled from the United States. Stephenson believed that Paine had been set-up as part of a FBI public relations exercise. He later recalled: "Adolf Berle was slightly school-masterish for a very brief period due to misinformation, but could not have been more helpful when factual situation was clarified to him."

William Boyd has argued the BSC "became a huge secret agency of nationwide news manipulation and black propaganda. Pro-British and anti-German stories were planted in American newspapers and broadcast on American radio stations, and simultaneously a campaign of harassment and denigration was set in motion against those organisations perceived to be pro-Nazi or virulently isolationist".

Keith Jeffery, the author of MI6: The History of the Secret Intelligence Service: 1909-1949 (2011) has pointed out: "The New York organisation expanded well beyond pure intelligence matters, and eventually combined the North American functions not just of SIS, but of M15, SOE and the Security Executive (which existed to co-ordinate counter-espionage and counter-subversion work): intelligence, security, special operations and also propaganda. Agents were recruited to target enemy or enemy controlled businesses, and penetrate Axis (and neutral) diplomatic missions; representatives were posted to key points, such as Washington, New Orleans, Los Angeles, San Francisco and Seattle; American journalists, newspapers and news agencies were targeted with pro-British material; an ostensibly independent radio station (WURL), with an unsullied reputation for impartiality, was virtually taken over." William Donovan, the chief of the Office of Strategic Service (OSS) has called the British Security Coordination (BSC) "the greatest integrated secret intelligence and operations organization that has ever existed anywhere".

History of British Security Coordination

At the end of the Second World War the files of British Security Coordination were packed onto semitrilers and transported to Camp X in Canada. Stephenson wanted to have some record of the activities of the agency, "To provide a record which would be available for reference should future need arise for secret activities and security measures for the kind it describes." He recruited Roald Dahl, H. Montgomery Hyde, Giles Playfair, Gilbert Highet and Tom Hill, to write the book. Stephenson told Dahl: "We don't dare to do it in the United States, we have to do it on British territory." Dahl commented: "He pulled a lot over Hoover... He pulled a few things over the White House, too, now and again. I wrote a little bit but eventually I called Bill and told him that it's an historian's job... This famous history of the BSC through the war in New York was written by Tom Hill and a few other agents." Only twenty copies of the book were printed. Ten went into a safe in Montreal and ten went to Stephenson for distribution.

In the 1960s Stephenson commissioned H. Montgomery Hyde, to write The Quiet Canadian (1962) about his work at the British Security Coordination. According to his biographer, David Hunt: "Its numerous invented stories, based on briefing from Stephenson, created a certain sensation but it still came short of Stephenson's inflated ideas; and as fresh revelations of British successes in the intelligence sphere continued to appear - for instance the Ultra secret - he clearly wished to claim credit for them." A classified CIA review said: "The publication of this study is shocking... Exactly what British intelligence was doing in the United States was closely held in Washington, and very little had hitherto been printed about it... One may suppose that Mr. Hyde's account... is relatively accurate, but the wisdom of placing it on the public record is extremely questionable."

Primary Sources

(1) Gill Bennett, Churchill's Man of Mystery (2009)

The story of the development of the Anglo-American Intelligence relationship, and in particular of British influence on the establishment in July 1941 of the US Coordinator of Information (COI), precursor of the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) established in June 1942 and of the post-war Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), remains the subject of research and some speculation. At the centre of the story and of the literature are two men who in the view of many (especially themselves) came to symbolise the Anglo-American Intelligence relationship, "Little Bill", later Sir William Stephenson, and Major-General William "Wild Bill" Donovan. Each is a figure about whom much myth has been woven, by themselves and others, and the full extent of their activities and contacts retains an element of mystery. Both were influential: Stephenson as head of British Security Coordination (BSC), the organisation he created in New York at Menzies's request and Donovan, working with Stephenson as intermediary between Roosevelt and Churchill, persuading the former to supply clandestine military supplies to the UK before the USA entered the war, and from June 1941 head of the COI and thus one of the architects of the US Intelligence establishment.

Morton's part in the story was largely that of intermediary. Contemporary American observers, such as US Ambassador in London Joseph Kennedy, his Military Attaché General Raymond E. Lee, and Ernest Cuneo, a US lawyer with close intelligence and political connections, saw him as a "top level operator", a "discreet and shadowy figure" with a "through wire" to Churchill." By this they meant that he was the man to approach with an urgent message for the Prime Minister. In respect of Stephenson and Donovan he was seen principally as a facilitator of what were assumed to be close personal relationships with Churchill enjoyed by both men. However, the evidence suggests that Churchill met Donovan on no more than one or two occasions, and may never have met Stephenson at all. Any dealings with the Prime Minister were conducted almost exclusively through Morton, a central point of contact. Churchill was uninterested in the detail of clandestine liaison arrangements, being concerned principally with his own relationship with Roosevelt, and with senior US representatives such as Harry Hopkins. He was also reluctant, in the summer of 1940 at least, "to give our secrets until the United States is much nearer to the war than she is now". He was content to leave intelligence liaison with Stephenson, Donovan and others to Morton on a personal, and Menzies on an operational, level.

It was, in fact, Menzies who was most effective in building the practical working relationship between British and American intelligence (and thereby laying the foundations for US post-war intelligence institutions). When Morton boasted to Colonel Ian Jacob in September 1941 that "to all intents and purposes US security is being run for them at the President's request by the British", he was referring to Stephenson and BSC: both reporting to Menzies. Stephenson, as we have seen, had approached SIS in 1939, with Morton's support, to secure Menzies' sponsorship for his industrial intelligence network.

No sooner had the arrangement been established satisfactorily in the spring of 1940, however, than Stephenson turned his attention, at Menzies's request, to exploring closer links with the US authorities; in particular, to establishing a closer relationship between SIS and the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). Stephenson had spent much time in the US, where Menzies wished to increase the scope of SIS operations, and to cooperate more closely with both official and less formal authorities, establishing his own channels rather than, for example, going through M15 to the FBI. At this stage there was no central coordination of "US Intelligence" in any institutional form, only disconnected and rival bodies that sought to draw on the experience of their British analogues: Menzies wanted it to be he, and SIS, that provided it.

(2) Stewart Menzies to Gladwyn Jebb (3rd June 1940)

I have appointed Mr W.S. Stephenson to take charge of my organisation in the USA and Mexico. As I have explained to you, he has a good contact with an official who sees the President daily. I believe this may prove of great value to the Foreign Office in the future outside and beyond the matters on which that official will give assistance to Stephenson. Stephenson leaves this week. Officially he will go as Principal Passport Control Officer for the USA. I feel that he should have contact with the Ambassador, and should like him to have a personal letter from Cadogan to the effect that it may at times be desirable for the Ambassador to have personal contact with Mr Stephenson.

(3) Adolph Berle, letter to Sumner Welles (31st March, 1941)

The head of the field service appears to be Mr. William S. Stephenson... in charge of providing protection for British ships, supplies etc. But in fact a full size secret police and intelligence service is rapidly evolving... with district officers at Boston, New York City, Philadelphia, Baltimore, Charleston, New Orleans, Houston, San Francisco, Portland and probably Seattle....

I have in mind, of course, that should anything go wrong at any time, the State Department would be called upon to explain why it permitted violation of American laws and was compliant about an obvious breach of diplomatic obligation... Were this to occur and a Senate investigation should follow, we should be on very dubious ground if we have not taken appropriate steps.

(4) Sidney Morrell, memo (10th July 1941)

(i) The Non-Sectarian Anti-Nazi League. Used for the vehement exposure of enemy agents and isolationists. Prints a wide variety of pamphlets, copies of which have been sent to you. Has recently begun to attack Lindbergh and the many other conscious or unconscious native Fascists....

(ii) The League for Human Rights. A subsidiary organization of the American Federation of Labour which in its turn controls 4,000,000 trade unionists....

(iii) Friends of Democacy. An example of the work of this organization is attached. It is a complete attack upon Henry Ford for his Nazi leanings.

(iv) Fight for Freedom Committee. Both this and (iii) above are militant interventionist organizations whose aim is to provide Roosevelt with evidence that the U.S. public is eager for action.

(v) American Committee to Aid British Labour. Another branch organization of tile American Federation of Labour. It is organized along the lines that British labour is in the front line defending American labour. The latest activity of this organization has been to inaugurate a week during which all American trade unionists are asked to donate towards a fund in aid of British labour....

(vi) Committee for Inter-American Co-operation. Used this for sponsoring SO.1 work in Central and South America. It is now being used intensively for penetration in all Latin American countries, both as cover for agents and for sponsoring pamphlets.

(vii) American Last. A purely provocative experiment started in San Francisco in an attempt to sting America into a fighting mood.

(5) Keith Jeffery, MI6: The History of the Secret Intelligence Service: 1909-1949 (2010)

Stephenson arrived in New York to take over as Passport Control Officer on Friday 21 June 1940. The following day France signed an armistice with the Germans, leaving Britain and the empire to stand alone. The official history of what became (from January 1941) British Security Co-ordination, which Stephenson had caused to be compiled in 1945, states that, before he left London, he "had no settled or restrictive terms of reference", but that Menzies "had handed him a list of certain essential supplies" which Britain needed. Menzies also laid down three primary concerns: "to investigate enemy activities, to institute adequate security measures against the threat of sabotage to British property and to organize American public opinion in favour of aid to Britain". With his headquarters on the thirty-fifth and thirty-sixth floors of the International Building in the Rockefeller Center, 630 Fifth Avenue, Stephenson built up a very extensive organisation, recruiting many staff from his native Canada, although Menzies sent the intelligence veteran C. H. (Dick) Ellis to be his second-in-command. The New York organisation expanded well beyond pure intelligence matters, and eventually combined the North American functions not just of SIS, but of M15, SOE and the Security Executive (which existed to co-ordinate counter-espionage and counter-subversion work): intelligence, security, special operations and also propaganda. Agents were recruited to target enemy or enemy controlled businesses, and penetrate Axis (and neutral) diplomatic missions; representatives were posted to key points, such as Washington, New Orleans, Los Angeles, San Francisco and Seattle; American journalists, newspapers and news agencies were targeted with pro-British material; an ostensibly independent radio station (WURL), "with an unsullied reputation for impartiality", was virtually taken over; and close liaison was established with the Royal Canadian Mounted Police. Stephenson also ran special operations throughout the western hemisphere and from July 1942 to April 1943 was put in charge of all SIS's South American stations.

(6) Conversation between William Stephenson and President Franklin D. Roosevelt (February, 1943)

Roosevelt: "Could Bohr be whisked out from under Nazi noses and brought to the Manhattan Project?"

Stephenson: "It will have to be a British mission. Niels Bohr is a stubborn pacifist. He does not believe his work in Copenhagen will benefit the Germany military caste. Nor is he likely to join an American enterprise which has as its sole objective the construction of a bomb. But he is in constant touch with old colleagues in England whose integrity he respects."

(7) William Allen White, interviewed in the Chicago Daily News (21st May, 1940)

Here is a life and death struggle for every principle we cherish in America: For freedom of speech, of religion, of the ballot and of every freedom that upholds the dignity of the human spirit... Here all the rights that common man has fought for during a thousand years are menaced... The time has come when we must throw into the scales the entire moral and economic weight of the United States on the side of the free peoples of Western Europe who are fighting the battle for a civilized way of life.

(8) Bill Macdonald, The True Intrepid: Sir William Stephenson and the Unknown Agents (2001)

The activities of BSC's Dennis Paine were another point of contention with American officials. In early 1942 the FBI claimed to have definite evidence that Dennis Paine of British intelligence in New York was conducting a Surveillance operation on assistant Secretary of State Adolf Berle, for the purpose of getting "dirt" on him, because he was thought to be anti-British. The FBI informed Berle that they had proof Paine had been conducting a campaign against him. The FBI wanted Paine out of the U.S. immediately, and if he wasn't out within 24 hours, they would arrest him. Berle called in Halifax and Stephenson to complain, and Paine was sent out of the country. Halifax and Stephenson were reported to have thoroughly objected to the deportation, and denied involvement, but Hoover was adamant.

Dennis Paine worked for Ross Smith, and he believes Paine was set up, perhaps by the FBI, to encourage more State Department control of BSC and OSS. Paine was known to the FBI through a German-speaking American FBI informer who patrolled the dock areas of New York picking up information in bars. "Paine may have used him as an informer himself." Ross Smith says Paine was his immediate assistant on the Ship's Observer Scheme, and was not involved in any type of surveillance.

Following the war Paine denied vehemently that he was involved, Ross Smith said. "The real outcome of this was that Berle was then able to put great pressure to bring all British intelligence activities to an end, and to try and bring British things under greater control. This was averted, however, by the intervention of Donovan." It was apparent to Ross Smith that if the Paine affair was not an FBI plot, it was a contrived attempt to get Berle to take action to try and get BSC under the control of the FBI.

(9) William Boyd, The Guardian (19th August, 2006)

"British Security Coordination". The phrase is bland, almost defiantly ordinary, depicting perhaps some sub-committee of a minor department in a lowly Whitehall ministry. In fact BSC, as it was generally known, represented one of the largest covert operations in British spying history; a covert operation, moreover, that was run not in Occupied France, nor in the Soviet Union during the cold war, but in the US, our putative ally, during 1940 and 1941, before Pearl Harbor and the US's eventual participation in the war in Europe against Nazi Germany...

After the fall of France in June 1940, Britain's position became even weaker - it was assumed that British capitulation was simply a matter of time; why join the side of a doomed loser, ran the argument in the US. Roosevelt's hands were therefore firmly tied. Much as he might have liked to help Britain (and this, I feel, is a moot point: just how enthusiastic was FDR himself?) he dared not risk alienating Congress - and he had a presidential election looming that he did not want to lose. To go to the country on a "Join the war in Europe" ticket would have been electoral suicide. He had to be very pragmatic indeed - and there was no greater pragmatist than FDR.

All the same, Churchill's task, as he himself saw it, was clear: somehow, in some way, the great mass of the population of the US had to be persuaded that it was in their interests to join the war in Europe, that to sit on the sidelines was in some way un-American. And so British Security Coordination came into being...

Stephenson called his methods "political warfare", but the remarkable fact about BSC was that no one had ever tried to achieve such a level of "spin", as we would call it today, on such a vast and pervasive scale in another country. The aim was to change the minds of an entire population: to make the people of America think that joining the war in Europe was a "good thing" and thereby free Roosevelt to act without fear of censure from Congress or at the polls in an election.

BSC's media reach was extensive: it included such eminent American columnists as Walter Winchell and Drew Pearson, and influenced coverage in newspapers such as the Herald Tribune, the New York Post and the Baltimore Sun. BSC effectively ran its own radio station, WRUL, and a press agency, the Overseas News Agency (ONA), feeding stories to the media as they required from foreign datelines to disguise their provenance. WRUL would broadcast a story from ONA and it thus became a US "source" suitable for further dissemination, even though it had arrived there via BSC agents. It would then be legitimately picked up by other radio stations and newspapers, and relayed to listeners and readers as fact. The story would spread exponentially and nobody suspected this was all emanating from three floors of the Rockefeller Centre. BSC took enormous pains to ensure its propaganda was circulated and consumed as bona fide news reporting. To this degree its operations were 100% successful: they were never rumbled.

Nobody really knows how many people ended up working for BSC - as agents or sub-agents or sub-sub-agents - although I have seen the figure mentioned of up to 3,000. Certainly at the height of its operations in late 1941 there were many hundreds of agents and many hundreds of fellow travellers (enough finally to stir the suspicions of Hoover, for one). Three thousand British agents spreading propaganda and mayhem in a staunchly anti-war America. It almost defies belief. Try to imagine a CIA office in Oxford Street with 3,000 US operatives working in a similar way. The idea would be incredible - but it was happening in America in 1940 and 1941, and the organisation grew and grew...

One of BSC's most successful operations originated in South America and illustrates the clandestine ability it had to influence even the most powerful. The aim was to suggest that Hitler's ambitions extended across the Atlantic. In October 1941, a map was stolen from a German courier's bag in Buenos Aires. The map purported to show a South America divided into five new states - Gaus, each with their own Gauleiter - one of which, Neuspanien, included Panama and "America's lifeline" the Panama Canal. In addition, the map detailed Lufthansa routes from Europe to and across South America, extending into Panama and Mexico. The inference was obvious: watch out, America, Hitler will be at your southern border soon. The map was taken as entirely credible and Roosevelt even cited it in a powerful pro-war, anti-Nazi speech on October 27 1941: "This map makes clear the Nazi design," Roosevelt declaimed, "not only against South America but against the United States as well."

The news of the map caused a tremendous stir: as a piece of anti-Nazi propaganda it could not be bettered. But was the South America map genuine? My own hunch is that it was a British forgery (BSC had a superb document forging facility across the border in Canada). The story of its provenance is just too pat to be wholly believable. Allegedly, only two of these maps were made; one was in Hitler's keeping, the other with the German ambassador in Buenos Aires. So how come a German courier, who was involved in a car crash in Buenos Aires, happened to have a copy on him? Conveniently, this courier was being followed by a British agent who in the confusion of the incident somehow managed to snaffle the map from his bag and it duly made its way to Washington.

The story of the South America map and the other BSC schemes was written up (in an extensive document of some hundreds of pages) after the war for private circulation by three former members of BSC (one of them Roald Dahl, interestingly enough). This secret history was a form of present for William Stephenson and a selected few others; it was available only in typescript and only 10 typescripts ever existed. Churchill had one, Stephenson had one and others were given to a few high officials in the SIS but they were regarded as top secret.

When Stephenson's highly colourful and vividly inaccurate biography was written (A Man Called Intrepid, 1976), the BSC typescript was drawn on by its author, but very selectively - in order to spare American blushes. The story of BSC seemed to be one of those wartime secrets that was never to be wholly revealed, like Bletchley Park and the Enigma machine decryptions. But the Enigma story was eventually made public and has been written about endlessly since the mid-1970s, fostering films, TV plays and novels in the wake of the revelations. But somehow BSC and the role of British agents in the US before Pearl Harbor has remained almost wholly undisclosed - one wonders why.

In 1998 the BSC typescript (one of only two remaining) was eventually published. To say it fell stillborn from the press would be an understatement. Yet here is a book of some 500 pages, written just after the war by former BSC agents, telling the whole story of Britain's US infiltration in great detail, recounting all the dirty tricks and the copious and widespread news manipulation that went on. I think it's fair to say that historians of the British Secret Services know about BSC and its operations, yet in the wider world it still remains virtually unheard of.

The reason is the story of BSC and its operations before Pearl Harbor is deeply embarrassing and remains so to this day. The document is explicit and condescending about American gullibility: "The simple truth is the United States is inhabited by people of many conflicting races, interests and creeds. These people, though fully conscious of their wealth and power in the aggregate, are still unsure of themselves individually, still basically on the defensive." BSC set out to manipulate "these people" and was very successful at so doing - hardly the kind of attitude countries involved in a "special relationship" should display. But that relationship is a Churchillian myth, invented and fostered by him after the war, and has been bought into wholesale by every subsequent British prime minister (with the possible exception of Harold Wilson).

As the secret history of the BSC unequivocally shows, sovereign states act exclusively to serve their own interests. A commentator in the Washington Post who read the BSC history remarked, "Like many intelligence operations, this one involved exquisite moral ambiguity. The British used ruthless methods to achieve their goals; by today's peacetime standards, some of the activities may seem outrageous. Yet they were done in the cause of Britain's war against the Nazis - and by pushing America towards intervention, the British spies helped win the war." Would BSC's activities eventually have encouraged the US to join the war in Europe? It remains one of the great "what ifs" of historical speculation. The tide of US public opinion seemed to be turning towards the end of 1941 - though isolationist sentiments remained very strong - and BSC's propaganda and relentless news manipulation deserved much of the credit for that change but, in the event, matters were taken out of BSC's hands. On the morning of Sunday, December 7 1941 the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor - the "day of infamy" had dawned and the question of American neutrality was gone for ever.

(10) Roald Dahl, H. Montgomery Hyde, Giles Playfair, Gilbert Highet and Tom Hill, British Security Coordination: The Secret History of British Intelligence in the Americas, 1940-45 (1945)

In the early spring of 1940, William Stephenson paid a visit to the United States. Ostensibly private business was the purpose of his journey. In fact, he travelled at the request of CSS.

He had received instructions which were explicit but limited in purpose to furthering Anglo-American cooperation in one specific field. He was required to re-establish on behalf of CSS a high-level liaison with the Federal Bureau of Investigation - a liaison which had been cut off as a result of British belligerency and American neutrality but without which SIS could not function effectively in the United States.

William Stephenson saw J. Edgar Hoover, Director of the FBI, and explained the purpose of his mission. Hoover said frankly that, while he himself was not opposed to working with SIS, he was under strict injunction from the State Department to refrain from collaboration with the British in any way which could be interpreted as an infringement of United States neutrality, and he made it clear that he would not be prepared to contravene this policy without direct Presidential sanction. Further, he stipulated that even if the President could be persuaded to agree to the principle of collaboration between the FBI and SIS, such collaboration should be effected initially by a personal liaison between William Stephenson and himself and that no other US government department, including the Department of State, should be informed of it.

Accordingly, William Stephenson arranged for a mutual friend to put the matter before the President, and Mr Roosevelt, upon hearing the arguments in favour of the proposed liaison, endorsed them enthusiastically. "There should be the closest possible marriage", the President said, "between the FBI and British Intelligence." Later, by way of confirmation, he repeated these words to HM Ambassador in Washington...

J. Edgar Hoover is a man of great singleness of purpose, and his purpose is the welfare of the Federal Bureau of Investigation. The FBI had already been in existence some years when, as a young man, Hoover was appointed its director nearly a quarter of a century ago. But he became its personification. He transformed it from a little known federal agency into a national institution, with a fabulous reputation for efficiency and achievement, an institution which is now regarded as the surest possible guarantee that crime in the United States cannot pay. Although Hoover is occasionally criticized in the liberal press on account of his suspected right-wing bias and anti-Communist phobia, the FBI has to endure none of that newspaper sniping against its usefulness to which other federal agencies, almost without exception, are periodically subjected. Its record has placed it above criticism.

Hoover has little time for leisure and few interests outside the FBI. His acquaintances are, therefore, predominantly made up of those with whom his work brings him into contact. To them he can be extremely affable, provided he is satisfied that they threaten neither directly nor indirectly the prestige and influence of the agency which he directs with such devotion. Hoover is in no way anti-British, but in every way pro-FBI. His job is at once his pride and his vanity. These facts are emphasized because they are fundamental to an understanding of the course of BSC's relationship with the FBI, which did not run smoothly throughout.

At the outset - and indeed until a few weeks before Pearl Harbor, when events, to be described in a subsequent chapter, caused a radical change in his attitude - Hoover could hardly have been more cooperative. Clearly William Stephenson's organization employing, as it did, not only its own intelligence agents but what amounted to its own police force represented an obvious threat to United States neutrality and could not have existed at all without the FBI's sanction.

(11) Roald Dahl, H. Montgomery Hyde, Giles Playfair, Gilbert Highet and Tom Hill, British Security Coordination: The Secret History of British Intelligence in the Americas, 1940-45 (1945)

The liaison with Hoover provided William Stephenson with a foundation upon which to build a secret organization in the United States. To achieve his immediate parallel purpose of obtaining certain essential supplies for Britain, he needed an intermediary par excellence for negotiations with the White House. In that respect it was fortunate that he was already well acquainted with William Joseph Donovan.

Donovan may be described as in every way a big man. He has great generosity of spirit, many enthusiasms and considerable breadth of interests. He is a former American football star and holder of the Congressional Medal of Honor which he won in the First World War, when he commanded the famous "Fighting 69th" and earned for himself the title "Wild Bill" Donovan - somewhat inappropriately, for though he is energetic and has a commanding personality, he is by nature modest and unassuming. In private life, he is a highly successful New York lawyer. He is self-made and has risen to his present eminence in what Americans like to call `the hard way'.

Though a member of the Republican Party, he exercised considerable influence in the inner councils of the Roosevelt Administration, for the Secretary of State, Cordell Hull, the Secretary of War, Henry Stimson, and the Secretary of the Navy, Frank Knox, were all his friends of long standing. Further, he was one of the President's most trusted personal advisers.

Donovan, by virtue of his very independence of thought and action, inevitably has his critics, but there are few among them who would deny the credit due to him for having reached a correct appraisal of the international situation in the summer of 1940. At that time the United States Government was debating two alternative courses of action. One was to endeavour to keep Britain in the war by supplying her with the material assistance of which she was desperately in need. The other was to give Britain up for lost and concentrate exclusively on American rearmament to offset the German threat. That the former course was eventually pursued is due in large measure to Donovan's tireless advocacy of it.

(12) William Stephenson, telegraph message to the head of the SIS (8th August, 1940)

Donovan greatly impressed by visit and reception... has strongly urged our case re destroyers... is doing much to combat defeatist attitude Washington by stating positively and convincingly that we shall win.

(13) William Stephenson, telegraph message to the SIS (21st August, 1940)

Donovan has urged upon President to see promised matters through himself with definite results ... Donovan believes you will have within a few days very favourable news... thinks he has restored confidence as to Britain's determination and ability to resist.

(14) Roald Dahl, H. Montgomery Hyde, Giles Playfair, Gilbert Highet and Tom Hill, British Security Coordination: The Secret History of British Intelligence in the Americas, 1940-45 (1945)

The first was Robert Sherwood, who, as his plays reveal, is an anglophile and a passionate anti-Fascist. It is now an open secret that Sherwood had a considerable hand in writing the President's more important speeches on international affairs, and he made a practice of showing each of these to WS (William Stephenson) while it was still in draft form, thus affording WS opportunity to suggest modifications, additions or deletions from the British point of view. He did this with the President's knowledge and approval.

(15) Roald Dahl, H. Montgomery Hyde, Giles Playfair, Gilbert Highet and Tom Hill, British Security Coordination: The Secret History of British Intelligence in the Americas, 1940-45 (1945)

The cooperation of newspaper and radio men was of the utmost importance. Without it, as will become apparent later on, many of BSC's operations against the enemy would have been impossible. Yet, in enlisting it, whether directly or through intermediaries, the greatest care had always to be exercised, for clearly if BSC had ever been uncovered or had the sources of its information been exposed, it would at once have been in the position of an overt British propaganda organization and as such considerably worse than useless. The conduct of its Political Warfare was entirely dependent on secrecy. For that reason the press and radio men with whom BSC maintained contact were comparable with sub-agents and the intermediaries with agents. They were thus regarded.