Ivar Bryce

Ivar Bryce was born in 1906. His father had made a fortune trading guano, the phosphate-rich deposit of fish-eating seabirds which had been widely used as a natural fertilizer. His mother was a painter and a published author of detective novels.

In 1917 Bryce met Ian Fleming and his brothers on a beach in Cornwall: "The fortress builders generously invited me to join them, and I discovered that their names were Peter, Ian, Richard and Michael, in that order. The leaders were Ian and Peter, and I gladly carried out their exact and exacting orders. They were natural leaders of men, both of them, as later history was to prove, and it speaks well for them all that there was room for both Peter and Ian in the platoon."

Bryce was sent to Eton College where he resumed his friendship with Fleming. Bryce purchased a Douglas motorbike and used this vehicle for trips around Windsor. He also took Fleming on the bike to visit the British Empire Exhibition in London. They also published a magazine, The Wyvern , together. Fleming used mother's contacts to persuade Augustus John and Edwin Lutyens, to contribute drawings. The magazine also published a poem by Vita Sackville-West. The editors showed their right-wing opinions by publishing an article in praise of the British Fascisti Party. It argued that its "primary intention is to counteract the present and every-growning trend towards revolution... it is of the utmost importance that centres should be started in the universities and in our public schools".

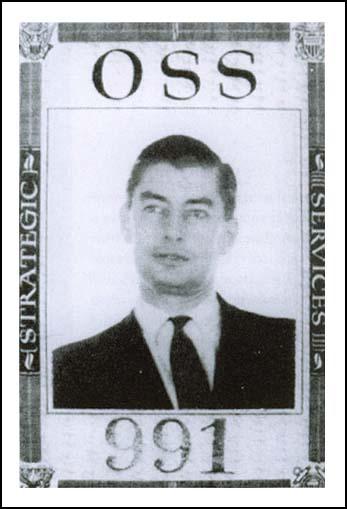

During the Second World War Bryce worked for William Stephenson, the head of British Security Coordination (BSC), a unit that was based in New York City. According to Thomas E. Mahl, the author of Desperate Deception: British Covert Operations in the United States, 1939-44 (1998): "Bryce worked in the Latin American affairs section of the BSC, which was run by Dickie Coit (known in the office as Coitis Interruptus). Because there was little evidence of the German plot to take over Latin America, Ivar found it difficult to excite Americans about the threat."

Nicholas J. Cull, the author of Selling War: The British Propaganda Campaign Against American Neutrality (1996), has argued: "During the summer of 1941, he (Bryce) became eager to awaken the United States to the Nazi threat in South America." It was especially important for the British Security Coordination to undermine the propaganda of the American First Committee that had over a million paid-up members. Bryce recalls in his autobiography, You Only Live Once (1975): "Sketching out trial maps of the possible changes, on my blotter, I came up with one showing the probable reallocation of territories that would appeal to Berlin. It was very convincing: the more I studied it the more sense it made... were a genuine German map of this kind to be discovered and publicised among... the American Firsters, what a commotion would be caused."

William Stephenson approved the idea and the project was handed over to Station M, the phony document factory in Toronto run by Eric Maschwitz, of the Special Operations Executive (SOE). It took them only 48 hours to produce "a map, slightly travel-stained with use, but on which the Reich's chief map makers... would be prepared to swear was made by them." Stephenson now arranged for the FBI to find the map during a raid on a German safe-house on the south coast of Cuba. J. Edgar Hoover handed the map over to William Donovan. His executive assistant, James R. Murphy, delivered the map to President Franklin D. Roosevelt. The historian, Thomas E. Mahl argues that "as a result of this document Congress dismantled the last of the neutrality legislation."

Nicholas J. Cull has argued that Roosevelt should not have realised it was a forgery. He points out that Adolf A. Berle, the Assistant Secretary of State for Latin American Affairs, had already warned Cordell Hull, the Secretary of State that "British intelligence has been very active in making things appear dangerous in South America. We have to be a little on our guard against false scares."

Bryce wrote to Walter Lippmann in March 1942. He sent him a book by Hugo Artuco Fernandez that had been written at the behest of British intelligence."I am sending you a copy of my friend Artuco's book, which I think will interest you... Some of it sounds rather alarming and exaggerated but it is much more accurate than most books on South America.... If you felt at all inclined to write anything about the dangers to South America, I could give you any number of facts which have never been published, but which my friends here would like to see judiciously made public at this point."

Bryce was based in Jamaica (his wife Sheila, owned Bellevue, one of the most important houses on the island), during the Second World War, where he ran dangerous missions into Latin America. Ian Fleming, who was personal assistant to Admiral John Godfrey, the director of naval intelligence, visited Bryce in 1941. Fleming told him that: "When we have won this blasted war, I am going to live in Jamaica. Just live in Jamaica and lap it up, and swim in the sea and write books."

In 1945 Bryce helped Fleming find a house and twelve acres of land just outside of Oracabessa. It included a strip of white sand on a lovely part of the coast. Fleming decided to call the house, Goldeneye, after his wartime project in Spain, Operation Goldeneye. Their former boss, William Stephenson, also had a house on the island overlooking Montego Bay. Stephenson had set up the British-American-Canadian-Corporation (later called the World Commerce Corporation), a secret service front company which specialized in trading goods with developing countries. William Torbitt has claimed that it was "originally designed to fill the void left by the break-up of the big German cartels which Stephenson himself had done much to destroy."

In 1950 Bryce married Josephine Hartford. Her grandfather, George Huntington Hartford, was the founder of the Great Atlantic and Pacific Tea Company. Josephine was the daughter of Princess Guido Pignatelli and Edward V. Hartford, who was an inventor and president of the Hartford Shock Absorber Company. A former concert pianist she was one of the leading racehorse owners in the United States.

Bryce joined with Ernest Cuneo and a group of investors, including Ian Fleming, to gain control of the North American Newspaper Alliance (NANA). Andrew Lycett has pointed out: "With the arrival of television, its star had begun to wane. Advised by Ernie Cuneo, who told him it was a sure way to meet anyone he wanted, Ivar stepped in and bought control. He appointed the shrewd Cuneo to oversee the American end of things... and Fleming was brought on board to offer a professional newspaperman's advice." Fleming was appointed European vice-president, with a salary of £1,500 a year. He persuaded James Gomer Berry, 1st Viscount Kemsley, that The Sunday Times should work closely with NANA. He also organized a deal with The Daily Express, owned by Lord Beaverbrook.

Bryce became a film producer and helped to finance The Boy and the Bridge (1959). The film lost money but Bryce decided he wanted to work with its director, Kevin McClory, again and it was suggested that they created a company, Xanadu Films. Josephine Hartford, Ernest Cuneo and Ian Fleming became involved in the project. It was agreed that they would make a movie featuring Fleming's character, James Bond.

The first draft of the script was written by Cuneo. It was called Thunderball and it was sent to Fleming on 28th May. Fleming described it as "first class" with "just the right degree of fantasy". However, he suggested that it was unwise to target the Russians as villains because he thought it possible that the Cold War could be finished by the time the film had been completed. He suggested that Bond should confront SPECTRE, an acronym for the Special Executive for Counterintelligence, Revolution and Espionage. Fleming eventually expanded his observations into a 67-page film treatment. Kevin McClory now employed Jack Whittingham to write a script based on Fleming's ideas.

The Boy and the Bridge was a flop at the box-office and Bryce, on the recommendation of Ernest Cuneo, decided to pull-out of the James Bond film project. McClory refused to accept this decision and on 15th February, 1960, he submitted another version of the Thunderball script by Whittingham. Fleming read the script and incorporated some of the Whittingham's ideas, for example, the airborne hijack of the bomb, into the latest Bond book he was writing. When it was published in 1961, McClory claimed that he discovered eighteen instances where Fleming had drawn on the script to "build up the plot".

President John F. Kennedy was a fan of Fleming's books. In March 1961, Hugh Sidey, published an article in Life Magazine, on President Kennedy's top ten favourite books. It was a list designed to show that Kennedy was both well-read and in tune with popular taste. It included Fleming's From Russia With Love. Up until this time, Fleming's books had not sold well in the United States, but with Kennedy's endorsement, his publishers decided to mount a major advertising campaign to promote his books. By the end of the year Fleming had become the largest-selling thriller writer in the United States.

This publicity resulted in Fleming signed a film deal with the producers, Albert Broccoli and Harry Saltzman, in June 1961. Dr No, starring Sean Connery, opened in the autumn of 1962 and was an immediate box-office success. As soon as it was released Kennedy demanded a showing in his private cinema in the White House.

Kevin McClory and Jack Whittingham became angry at the success of the James Bond film and believed that Bryce, Ian Fleming and Ernest Cuneo had cheated them out of making a profit out of their proposed Thunderball film. The case appeared before the High Court on 20th November 1963. Three days into the case, when President John F. Kennedy was assassinated in Dallas. McClory's solicitor, Peter Carter-Ruck, later recalled: "The hearing was unexpectedly and somewhat dramatically adjourned after leading counsel on both sides had seen the judge in his private rooms." Bryce agreed to pay the costs, and undisclosed damages. McClory was awarded all literary and film rights in the screenplay and Fleming was forced to acknowledge that his novel was "based on a screen treatment by Kevin McClory, Jack Whittingham and the author."

Fleming encouraged Bryce to write his memoirs and gave him some advice on how to deal with the process. "You will be constantly depressed by the progress of the opus and feel it is all nonsense and that nobody will be interested. Those are the moments when you must all the more obstinately stick to your schedule and do your daily stint... Never mind about the brilliant phrase or the golden word, once the typescript is there you can fiddle, correct and embellish as much as you please. So don't be depressed if the first draft seems a bit raw, all first drafts do. Try and remember the weather and smells and sensations and pile in every kind of contemporary detail. Don't let anyone see the manuscript until you are very well on with it and above all don't allow anything to interfere with your routine. Don't worry about what you put in, it can always be cut out on re-reading; it's the total recall that matters." Bryce's autobiography, You Only Live Once, was published in 1975.

Ivar Bryce died in 1985.

Primary Sources

(1) Ivar Bryce, You Only Live Once (1975)

The fortress builders generously invited me to join them, and I discovered that their names were Peter, Ian, Richard and Michael, in that order. The leaders were Ian and Peter, and I gladly carried out their exact and exacting orders. They were natural leaders of men, both of them, as later history was to prove, and it speaks well for them all that there was room for both Peter and Ian in the platoon.

(2) Andrew Lycett, Ian Fleming (1996)

With the arrival of television, its star had begun to wane. Advised by Ernie Cuneo, who told him it was a sure way to meet anyone he wanted, Ivar stepped in and bought control. He appointed the shrewd Cuneo to oversee the American end of things... and Fleming was brought on board to offer a professional newspaperman's advice.