Robert E. Sherwood

Robert Emmet Sherwood, the son of Arthur Murray Sherwood, a rich stockbroker, and his wife, the former Rosina Emmet, was born in New Rochelle on 4th April 1896. He was a great-grandnephew of the Irish nationalist Robert Emmet who was executed for high treason in 1803.

Sherwood's mother had been a student at the Arts Students League before becoming a successful artist whose illustrations had appeared in magazines, including Harper's Weekly and Century Magazine. She also provided the artwork for several children's book.

Rosina had married late in life and did not start a family until she was 33 years old. She had five children: Arthur (1888), Cynthia (1889), Philip (1891), Robert (1896) and Rosamund (1899). His father was a very successful stockbroker and the family enjoyed a privileged life. This included owning a summer house near Lake Champlain and the employment of several servants. Robert was a very tall child and after hearing about the "freaks" in the sideshow of a visiting circus, he said to his mother: "I do hope to goodness I'm not going to be a freak. I suppose the only kind of freak I could be would be a giant and I hope I'm not going to be that."

At the age of eight Robert was sent away to boarding school in Southborough, Worcester County. His headmaster, Waldo B. Fay, held progressive views on education and during his time at the school he became very interested in creative writing. Robert also enjoyed writing and acting in plays. During his holidays in Westport Island he played a key role in the town's annual musical and a vaudeville-style concert. Gretchen Finletter, one of his friends, later commented that he was always writing plays: "He saw a drama perfect and whole in his head".

In September 1909 Sherwood was sent to Milton Academy. According to his biographer, John Mason Brown, the author of The Ordeal of a Playwright; Robert E. Sherwood and the Challenge of War (1970), Sherwood was a recalcitrant student and suffered regular beatings. Brown claims that in an effort to destroy the reports of his bad behaviour, he accidentally set fire to a classroom. Harriet Hyman Alonso has pointed out: "In spite of his bad behavior and poor grades, Bobby loved Milton Academy, and as an adult kept in touch with the institution." Sherwood later recalled: "I don't believe there are many boys at any school who received so much in the way of tolerance, understanding, and superhuman forgiveness as I did at Milton."

Sherwood entered Harvard University in 1914. He excelled in the arts and creative writing but did badly in other subjects. At the mid-point of his first year he received D's in Greek, Latin, History, Geography and Algebra and the college's administrative board considered placing him on probation. The following year the threat was carried out after continued poor grades. He later admitted that instead of studying his time was mainly "filled with attending movies, plays, and musicals, drinking and carousing with friends in local pubs, or writing stories and drawing cartoons". He was so busy writing plays for the local theatre group that he "overlooked the dreary duties involved in getting an education".

His mother, Rosina Sherwood, wrote to Harvard and claimed: "He will always be careless and odd, but he has lots of ability which will probably someday be turned to journalism or playwriting perhaps." Sherwood later told a young college student that he regretted his lack of effort at university: "I spent the rest of my life regretting how stupidly and lazily I had wasted those two and a half years at Harvard, and of all the time I had expended subsequently educating myself to make up for my failure to take advantage of the wasted opportunities at college."

Sherwood believed that the United States should be involved in the First World War. After the German U-boat sank the British liner, Lusitania, resulting in the death of 1,198 people, 128 of them from the United States, he enrolled in the Reserve Officers Training Corps (ROTC). On 2nd April 1917, President Woodrow Wilson asked Congress to declare war on Germany. Four days later the resolution passed the Senate 86 to 6 and the House of Representatives 373 to 50.

Sherwood immediately attempted to join the United States Army. However, he was rejected because he was considered that at over 6 feet 6 inches, he was too tall in proportion to his weight of 167 pounds for military service. He therefore turned his attention to the Canadian Expeditionary Force which was desperately short of men as they had been fighting since 1914. On 3rd July 1917 he was accepted as being "fit for General Service".

Sherwood was assigned to the Canadian Black Watch in Montreal. They had no boots large enough to fit him and had to wear his own size 13D shoes. They were unable to find a uniform and he had to have a special one made for him. An army doctor also told him that because he was so tall he would not be allowed to serve in the trenches. This decision was later overruled.

On 23rd February, 1918, Sherwood and his unit arrived in France. The contents of Sherwood's seventy-pound pack consisted of "a thick greatcoat, an equally substantial sweater, a leather buff coat-as solid and stiff as a breast plate; a haversack with our polishing and toilet kit; a steel helmet; a bayonet; a spade with a long wooden handle; gas mask; mess tin; blanket and rubber sheet, and, last, but not least, 120 rounds of ammunition."

According to Harriet Hyman Alonso, the author of Robert E. Sherwood The Playwright in Peace and War (2007): "Trench life, in particular, was one of the most wearying experiences of the war. The physical conditions alone were very hard. Thousands of men were packed together for weeks and months at a time in what were basically narrow gullies without permanent tops. Interconnecting branches led to sections where officers might have makeshift quarters, supplies could be kept, and the injured might be cared for. Men in the trenches were exposed to all of nature's wrath - rain, snow, cold, fog, and intense sun. Day and night they lived outdoors, the only relief being provided by cave-like dugouts where they took breaks to sleep, eat, play poker, and tell stories of their trysts with Frenchwomen while on leave in Paris. At its best, trench life was excruciatingly boring as soldiers waited for their next foray into enemy territory or the enemy's into theirs. At worst, it was wet, muddy, and constantly damp. Death could come quickly from illness, a sniper's good shot, a poison gas shelling, or an attack, and corpses could not always be removed immediately."

For several weeks Sherwood served as part of the working party digging trenches in Arras on Vimy Ridge. This was usually done at night, when each man was responsible for enlarging the trench by three or four yards. During this period his regiment was presented to George V and Sir Douglas Haig. The king went over to Sherwood and asked him how tall he was. This was followed by other questions and he was very surprised to find out he was not a Canadian.

In July 1918 Sherwood regiment experienced a German mustard gas attack. Although he had been given a gas mask he either had trouble putting it on or had taken it off too soon. He was hospialized after having vomited for approximately two hours. He was eventually released from hospital sent back to the Western Front with the recommendation that he be assigned only "light duties". He later recalled: "my youthful enthusiasm was drained out of me. I was scared stiff. I thought, In a few days or maybe, a few hours, how do I know? I'll be up in that terror. Let's face it I'm going to be killed in this war. And that's the end of me."

Sherwood was sent into No Man's Land for the first time on 7th August 1918. His battalion's task was to reach the village of Hourges near Amiens. The contents of Sherwood's seventy-pound pack consisted of "a thick greatcoat, an equally substantial sweater, a leather buff coat-as solid and stiff as a breast plate; a haversack with our polishing and toilet kit; a steel helmet; a bayonet; a spade with a long wooden handle; gas mask; mess tin; blanket and rubber sheet, and, last, but not least, 120 rounds of ammunition." The author of The Ordeal of a Playwright; Robert E. Sherwood and the Challenge of War (1970) claims that he "suffered horribly from gas" before falling into a pit dug by the Germans that was filled with sharp stakes and tangles of barbed wire. On the day he was injured, 1,036 Canadians were killed. A further 2,803 were wounded and 29 were taken prisoner.

After treatment at a casualty clearing station Sherwood was sent to England for further treatment. While in a hospital in Bexhill-on-Sea the Armistice was signed. He was shipped back to Montreal in January 1919. The following month he was handed his discharge papers, which stated that he was "medically unfit" for service. On arriving home he told his mother that during his seven months in France, the personnel in his company had changed twice because every officer and enlisted man had been either killed or wounded during the fighting. As a result of his experiences during the First World War, Sherwood became a pacifist.

Sherwood's mother used her contacts to get her son a job with Vanity Fair. He was paid $25 a week to carry out menial tasks. He later described it as "a sort of maid of all work". An old college pal, Robert Benchley, also worked on the magazine. Harriet Hyman Alonso has pointed out: "Benchley was a man whom Bob had admired since first seeing him at Harvard, where Benchley was a student in the class of 1912. At Bob's freshman smoker he gave the featured speech and then spent time with the new students, drinking beer, smoking, and generally joking around." With the support of Benchley he began writing signed articles for the magazine.

Sherwood also became friends with another contributor Dorothy Parker. She later told the story of how he always passed by the Hippodrome Theatre when he went to lunch. At the time it was featuring a number of midgets, who harassed him by jeering at him, pretending to nibble at his knees and "always sneaking up behind him and asking him how the weather was up there." According to Parker, Sherwood asked her for help: "Mr. Benchley and I would leave our jobs and guide him down the street."

Sherwood, Parker and Benchley lunched together in the dining room at the Algonquin Hotel. Sherwood was six feet eight inches tall and Benchley was around six feet tall, Parker, who was five feet four inches, once commented that when she, Sherwood and Benchley walked down the street together, they looked like "a walking pipe organ."

After a time they were joined by other writers such as Dorothy Parker, Robert Benchley, Alexander Woollcott, Heywood Broun, Harold Ross, Donald Ogden Stewart, Edna Ferber, Ruth Hale, Franklin Pierce Adams, Jane Grant, Neysa McMein, Alice Duer Miller, Charles MacArthur, Marc Connelly, George S. Kaufman, Beatrice Kaufman , Frank Crowninshield, Ben Hecht, John Peter Toohey, Lynn Fontanne, Alfred Lunt and Ina Claire. The owner of the hotel, Frank Case, decided that it would be a good idea to cultivate this group of writers as it might attract more diners. He moved them to a central spot at a round table in the Rose Room, where others could watch them enjoy each other's company. This group eventually became the Algonquin Round Table.

The group played games while they were at the hotel. One of the most popular was "I can give you a sentence". This involved each member taking a multi syllabic word and turning it into a pun within ten seconds. Dorothy Parker was the best at this game. For "horticulture" she came up with, "You can lead a whore to culture, but you can't make her think." Another contribution was "The penis is mightier than the sword." They also played other guessing games such as "Murder" and "Twenty Questions".

Dorothy Parker developed a reputation for making harsh comments in her reviews and on 12th January 1920 she was sacked by Frank Crowninshield, the editor of Vanity Fair. He told her that complaints about her reviews had come from three important theatre producers. Florenz Ziegfeld was particularly upset by Parker's comments about his wife, Billie Burke: "Miss Burke is at her best in her more serious moments; in her desire to convey the girlishness of the character, she plays her lighter scenes as if she were giving an impersonation of Eva Tanguay."

Sherwood and Robert Benchley both resigned over the sacking. As John Keats, the author of You Might as Well Live: The Life and Times of Dorothy Parker (1971): "It is difficult now to imagine a magazine of Vanity Fair's importance then truckling to Broadway producers, but the newspapers and magazines of 1920 did, and this was a sore point to the working newspapermen and theatre critics at the Round Table. They believed that if an actor was guilty of overacting, it was no more and no less than a critic's duty to report that he was - producers be damned. Furthermore, in this case, Vanity Fair's position seemed to be one of accepting a complaint from an advertiser as sufficient excuse to fire an employee with no questions asked, and it was the injustice of this position that led Mr Benchley and Mr Sherwood to tell Mr Crowninshield that if he was going to fire Mrs Parker, they were quitting."

In 1920 Sherwood became assistant editor of Life Magazine. One of the first things that he did was to recruit Robert Benchley as the magazine's drama critic and Dorothy Parker supplied regular poems. In January 1921, Sherwood became the magazine's film reviewer. It has been claimed that he was the first serious film critic in the world and was described by the journalist, Richard Watts, as "the dean of motion picture criticism". His reviews were syndicated and appeared in Photoplay, Movie Weekly, McCall's Magazine and the New York Herald Tribune.

On 30th April 1922, members of the Algonquin Round Table produced their own one-night vaudeville review, No Siree!: An Anonymous Entertainment by the Vicious Circle of the Hotel Algonquin . It included a monologue by Robert Benchley, entitled The Treasurer's Report . Marc Connelly and George S. Kaufman contributed a three-act mini-play, Big Casino Is Little Casino , that featured Sherwood. The show included several musical numbers, some written by Irving Berlin. One of the most loved aspects of the show was the Dorothy Parker penned musical numbers that were sang by Tallulah Bankhead, Helen Hayes, June Walker and Mary Brandon.

Sherwood continued to review movies. In 1923 he claimed he saw every film that was released, "about two hundred feature films a year, and a great many shorter pictures... something like twenty-five hundred reels, which, when resolved into terms of linear measure, amounts to two million, five hundred thousand feet, or over four hundred miles." Each week he reviewed around four films. He once wrote that "film is the tenth art" and although "allied to other arts in various degrees and greater in its appeal than all of them."

Sherwood argued that Charlie Chaplin was "the greatest genius that the cinema has developed" and suggested that Harold Lloyd and Buster Keaton were "not far behind". He considered Rex Ingram the the best director and Karl Brown an outstanding cinematographer. He also praised the talents of Mary Pickford, Douglas Fairbanks and Jackie Coogan but believed the star system was a "gross exaggeration of actors' talents". He considered Chaplin's Shoulder Arms (1918) as the "greatest comedy in movie history".

Early on Sherwood decided his role was to educate the public about good movies. This included documentaries such as Nanook of the North (1922) about Eskimo life and Down to the Sea in Ships (1923), about New Bedford, Massachusetts. He claimed the film's scene of whale hunting was "one of the most realistically thrilling episodes" he had ever witnessed on the screen.

Sherwood was especially interested in films about war. He argued that the First World War was "the first great historical event to be chronicled by means of the motion picture camera". He was extremely disappointed with the films that were released after the war. Sherwood wrote in Vanity Fair that the stories generally featured a mythical soldier who "(1) captured a village, practically single-handed, just in time to save an exquisite French girl from an unspeakable fate. (2) lay wounded in the heart of No-Man's Land until rescued by the Red Cross dog. (3) received the Légion d'honneur and a kiss from Marshall Foch... (4) returned home to find that he had been given up for lost by everyone except her - who had never wavered for so much as an instant."

In a review of The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse (1921) Sherwood argued that it was the responsibility of the director to capture the reality of the war because within a hundred years there would no longer be any survivors who could relate their stories first hand: "It is quite important, therefore, that we get the record straight, and make sure that nothing goes down to posterity which will mislead future generations into believing that this age of ours was anything to brag about." He suggested that people should read the work of Philip Gibbs and Henri Barbusse and "if after reading these, he is still doubtful of the fact that war is essentially a false, hideous mistake" he should watch this film.

Another film about the First World War that he recommended was the French film J'Accuse. He also praised What Price Glory? (1926) for "some tremendously effective war scenes" and was pleased that director Raoul Walsh was not afraid "to picture the unmitigated brutality" of war. In contrast, he hated Lost at the Front (1927) for not showing the reality of trench warfare: "Nearly nine years have passed since the Armistice was signed, but we are still suffering from the horrors of the war in the form of this comedy."

Sherwood thought the most authentic depiction of the battlefront appeared in the film The Big Parade (1925): "When he (the director) advances a raw company of infantry through a forest which is raked by machine gun fire, he makes his soldiers look scared, sick at their stomachs, with no heart for the ghastly business that is ahead." Sherwood praised the director, King Vidor, for making a film that did not include "one error of taste or of authenticity". He pointed out a scene where the director films a close-up of the actor's face while he is killing a German soldier: "I doubt that there is a single irregular soldier, volunteer or conscripted, who did not experience that awful feeling during his career in France - who did not recognize the impulse to withdraw the bayonet and offer the dying Heine a cigarette."

Sherwood strongly disliked The Birth of a Nation with its pro-Ku Klux Klan stance and its endorsement of slavery but rejected the argument of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) that it should be banned. Sherwood was passionately against censorship as he considered it a question of human rights as well as artistic expression. Sherwood believed censorship was anti-democratic as it gave power to a small group of people, allowing them to "cut off access to knowledge, culture and entertainment to the many."

In January 1922, Will H. Hays was appointed as President of the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America (MPPDA). The main objective of the organization was to improve the image of the movie industry after the alleged rape and murder of actress Virginia Rappe, for which film star Fatty Arbuckle had been arrested. Hays was instructed to "clean up the pictures". Sherwood objected to this attempt at censorship. He declared: "We don't need censors to cleanse the movies. Most pictures are too blatantly wholesome as it is." He argued that what cinema visitors needed to "promote the standard of intelligence on the screen".

On 29th October 1922 Sherwood married the actress Mary Brandon. His biographer, John Mason Brown, the author of The Ordeal of a Playwright; Robert E. Sherwood and the Challenge of War (1970), portrays Mary as a woman full of contradictions: "She appeared soft and was tough, seemed yielding and was demanding. She was self-absorbed to the point of egomania, self-deluding to the verge of pathos, and bantam in everything except her faults." A daughter, Mary, was born on 26th October, 1923. Dorothy Parker sent the new mother a telegram that read: "Dear Mary, we all knew you had it in you."

Sherwood wrote in an article that appeared in Life Magazine on 25th January, 1925: "Show me a critic and I, in my turn, will show you a man who is constantly persuading himself that some day he is going to write something worth while... and that his criticism of others provides him with an elm-lined avenue of escape. He derives an unholy delight from the spectacle of someone else failing to do the thing at which he himself has failed."

During this period Sherwood made several attempts to write plays that could be performed on Broadway. His friend, Edna Ferber from the Algonquin Round Table had a big hit with her novel Show Boat (1926). She told Sherwood that he was wasting his time with too much socializing and should be spending his spare hours producing something worthwhile. He took her advice and began work on an anti-war play.

Sherwood later wrote: "To be able to write a play a man must be sensitive, imaginative, naive, gullible, passionate: he must be something of an imbecile, something of a poet, something of a liar, something of a damn fool... He must be prepared to make a public spectacle of himself. He must be independent and brave." His first play, The Road to Rome , was produced in New York City in 1927. The story is about Hannibal and deals with his attempt to conquer Rome during the Second Punic War. Sherwood created the character of Amytis, the fictional wife of Fabius Maximus, who visits Hannibal in his camp before the attack on Rome. Amytis questions the Carthaginian commander about the morality of war. The two spend the night together and the next morning Amytis goes back to Rome and Hannibal withdraws his troops.

The Road to Rome received generally good reviews. Charles Brackett of the New Yorker praised it as "a hymn of hate against militarism - disguised, ever so gaily, as a love song." Alexander Woollcott wrote in the New York World that the play was "wise and lofty and searching and good... it is definitely a play written in the aftermath of the war". Brooks Atkinson of the New York Times saw it as a political satire in the style of George Bernard Shaw and considered the play "mechanical and obvious" whereas Percy Hammond of the New York Herald Tribune accused Sherwood of preaching "a sermon for pacifism".

The play ran for 392 performances before going on tour. On its opening-night in London the cast gave the cast 15 curtain calls. The play was such a success Sherwood was invited to Hollywood and his first screenplay, The Private Life of Helen of Troy, was based on his first play. This was followed by The Queen's Husband (1931), Waterloo Bridge (1931), The Age for Love (1931), Two Kinds of Women (1932), Cock of the Air (1932) and Reunion in Vienna (1933).

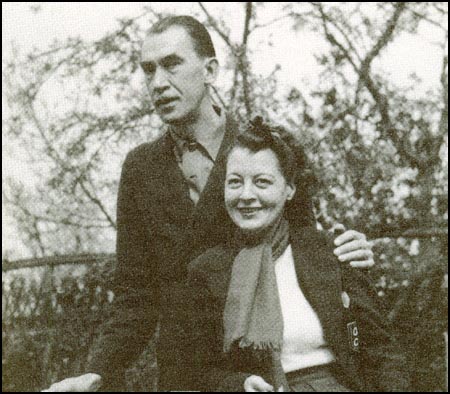

In 1932 Sherwood began an affair with the former successful actress, Madeline Hurlock, and the wife of Marc Connelly. According to one source "Marc Connelly had always treated her unkindly". Sherwood's wife, Mary Brandon, was also having an affair. When he discovered this he hired private detectives to produce the evidence that would entitle him to go to court and request custody on the grounds that she was an unfit mother. They were divorced on 17th June 1934. The following year he married Madeline.

Sherwood's next play was The Petrified Forest. It previewed in Hartford, Connecticut, on 10th December, 1934, and opened at the Broadhurst Theatre in New York City on 7th January, 1935. The story concerns a young woman Gabby Maple (Peggy Conklin) who works in a restaurant in Arizona, who falls in love with Alan Squier (Leslie Howard), a failed author who meets her on his way to California. She considers going away with him when an escaped criminal Duke Mantee (Humphrey Bogart) arrives and holds them hostage.

The play was well received by the critics. John Howard Lawson described it as "among the most distinguished products of the English-speaking stage". Brooks Atkinson praised Sherwood's "earnest idealism" and described it as "literate melodrama" whereas Richard Watts saw it as "patriotic". Burns Mantle found it an "effective melodrama with an interesting philosophic content uncommon in dramas of so patent a theatrical base." The play ran on Broadway for 194 performances and had a successful tour. It was also used as the basis for the movie The Petrified Forest (1936).

Sherwood remained very interested in politics and wrote in his diary that all his writing was concerned with "reforming the world". His next play, Idiot's Delight, was concerned with the growing power of Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini. It was also concerned with the industrialists who made money from war and was inspired by the report published by Gerald Nye that revealed details of how this happened during the First World War. He wrote in his diary: "I believe that such people are the arch villains of mortal creation. What has clinched my determination is reading in Time a quotation from Sir Herbert Laurence of Vickers, 'The sanctity of human life has been exaggerated.' Such men are sons of bitches and should be so represented."

The play opened in New York City on 24th March, 1936. Sherwood was afraid the play was too political but after 19 curtain calls and "vociferous cheers" he could relax. Percy Hammond thought it was "excellent" and successfully dealt with the "stern and foolish arbitrament of arms". John Anderson of the New York Evening Journal-American claimed: "Some of us had just seen a momentous play and were feeling a little unsteady; some of us had just seen the most peaceful warrior among our playwrights deliver, with shattering impact and unfaltering aim, a blow against the stupidity of war." John Mason Brown of the New York Post said Sherwood had the "uncommon ability to combine entertainment of a fleet and satisfying sort with an allegory which reaches for a larger meaning." Idiot's Delight was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for drama that year.

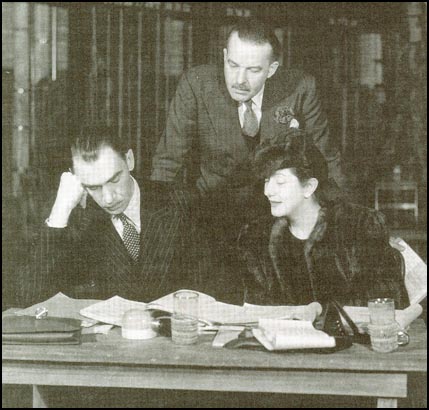

On 12th April, 1938, Sherwood joined up with Elmer Rice, Maxwell Anderson, Samuel Behrman, and Sidney Howard to establish the Playwrights Company. They all signed an agreement which stated their intention to produce their own plays and those of other playwrights as well. All five agreed to raise $10,000 for starting capital. They also employed John Wharton as a lawyer, Victor Samrock, as their general manager and William Fields, as their press agent.

Sherwood responded to his fears of fascism by writing a play about Abraham Lincoln. Over the next few months he read everything about Lincoln he could and other associates including Mary Todd Lincoln, William Herndon, Stephen A. Douglas and Joshua Speed. He wrote in his diary that maybe he had done "too much reading" and had therefore created a historical document "instead of what it should be - a play by me."

After seeing Raymond Massey in a film, he became convinced that he had found the ideal actor to play Lincoln. Sherwood said the play was "the story of a man of peace who had to face the issue of appeasement or war". Sherwood wrote that Lincoln embodied "all the contrasted qualities of the human race - the hopes and fears, the doubts and convictions, the mortal frailty and superhuman endurance, the prescience and the neuroses, the desire to escape from reality, and the fundamental unshakeable nobility... He was a living American and in his living words are the answers... to all the questions that distract the world today."

Sherwood was appalled by the signing of the Munich Agreement. On 21st September 1938, he wrote in his diary that a war with Adolf Hitler was now inevitable and that he was no longer a pacifist: "I feel that I must start to battle for one thing: the end of our isolation. There is no hope for humanity unless we participate vigorously in the concern of the world and assume our proper place of leadership with all the grave responsibilities that go with it."

Abe Lincoln in Illinois opened at the Plymouth Theatre on 15th October, 1938. It was produced by the Playwrights Company and directed by his close friend and anti-fascist campaigner, Elmer Rice. According to Harriet Hyman Alonso, the author of Robert E. Sherwood The Playwright in Peace and War (2007): "Abe Lincoln in Illinois is a play about soul-searching... It was written about three men - Abraham Lincoln, Franklin D. Roosevelt and Robert E. Sherwood - and their search for an answer to their moral aversion to war in a world in which horrific deeds were being committed."

President Franklin D. Roosevelt, like Abraham Lincoln and Sherwood, was moving away from neutrality and appeasement. The same month that the play opened, Roosevelt asked Congress to allocate $300 million for defence spending and asked them to repeal the arms embargo law so that in case of war, Britain and France could purchase weapons. He also spoke out against Hitler's persecution of the Jews and recalled the U.S. ambassador to Germany.

Abe Lincoln in Illinois was a great success and had 472 performances on Broadway. A film of the play appeared the following year. The Playwrights Company next production was Knickerbocker Holiday (1938), a musical by Maxwell Anderson and Kurt Weill, it was considered a success with 168 performances. This was followed by American Landscape (1938) by Elmer Rice, No Time for Comedy (1939) by Samuel Behrman and Key Largo (1939) by Anderson. Only the Rice play failed to make money.

when writing There Shall Be No Night.

Sherwood's next play was There Shall Be No Night. The play is set in Finland between 1938 and 1940 and concerns Kaarlo Valkonen (Alfred Lunt) who has just won the Nobel Prize in medicine for his work on the causes of insanity. His wife, American-born Miranda Valkonen (Lynn Fontanne) is, like her husband, is a pacifist, who refuses to believe that the country will be invaded by the Soviet Union. Their son, Erik Valkonen (Montgomery Clift), is not so confident and is a member of the Finnish Army.

After the Red Army invade and enters the university where he teaches, Kaarlo, who has now abandoned his pacifism, says to his wife: "I am trying to defeat insanity... the degeneration of the human race... and then a band of pyromaniacs enters the building in which I work. And that building is the world - the whole planet - not just Finland. They set fire to it. What can I do? Until the fire is put out, there can be no peace - no freedom from fear - no hope of progress for mankind."

There Shall Be No Night opened at the Alvin Theatre on 29th April, 1940. Maxwell Anderson commented that he was proud of Sherwood "for having raised your voice and spoken out like a man at a fire when everybody else (including myself) was still clinging to dubious hopes. It's seldom that anybody is so prophetically accurate and right." Felix Frankfurter wrote to Sherwood arguing: "You have again proven that art affords the most powerful access to minds and feelings... It is the artist's function to make his perception contagious, and that you have done superbly in your play... Everyone who cares about the painfully gained achievements of civilization - one ought not to be ashamed to express ultimate beliefs these days - is your debtor."

After 181 performances on Broadway the play went on tour. Robert McCormack, a member of the pro-isolationist America First Committee, ordered that his newspaper, the Chicago Tribune, should not publish one word about the play. Despite the criticism the play was a great success with audiences and in 1940 alone Sherwood's royalties amounted to $64,889.00. A large proportion of this was donated to organizations such as the Red Cross, Committee against Nazi Propaganda and the Canadian Hurricane Spitfire Fund. The play also won the Pulitzer Prize for Drama. It was also a great success in London where it ran for several years during the Second World War.

Winston Churchill became prime minister in May 1940. Churchill realised straight away that it would be vitally important to enlist the United States as Britain's ally. Randolph Churchill, on the morning of 18th May, 1940, claims that his father told him "I think I see my way through.... I mean we can beat them." When Randolph asked him how, he replied with great intensity: "I shall drag the United States in." Churchill sent William Stephenson to the United States to establish the British Security Coordination. Soon afterwards Ernest Cuneo, introduced Stephenson to Sherwood. Cuneo told Sherwood that the president wanted "the closest possible marriage between the FBI and British Intelligence." Stephenson later claimed that Sherwood was "one of the most persistent and effective" of those contacts with "influence at the White House".

As William Boyd has pointed out: "The phrase (British Security Coordination) is bland, almost defiantly ordinary, depicting perhaps some sub-committee of a minor department in a lowly Whitehall ministry. In fact BSC, as it was generally known, represented one of the largest covert operations in British spying history... With the US alongside Britain, Hitler would be defeated - eventually. Without the US (Russia was neutral at the time), the future looked unbearably bleak... polls in the US still showed that 80% of Americans were against joining the war in Europe. Anglophobia was widespread and the US Congress was violently opposed to any form of intervention."

Sherwood agreed to help the British Security Coordination. As he pointed out in his book, Roosevelt and Hopkins: An Intimate History (1948): "Six months before the United States entered the war... there was, by Roosevelt's order and despite State Department qualms, effectively close cooperation between J. Edgar Hoover and the FBI and British security services under the direction of the quiet Canadian, William Stephenson... If the isolationists had known the full extent of the secret alliance between the U.S. and Britain, their demands for the President's impeachment would have rumbled like thunder across the land." One of his tasks was to attack isolationists such as Charles Lindbergh and Henry Ford. In one article he claimed that they were "two outstanding exponents of what I and many other Americans consider a traitorous point of view."

Sherwood was introduced to President Franklin D. Roosevelt by Harry Hopkins. In October 1940 he agreed to join Hopkins and Samuel Rosenman to write speeches for the president. Edmond Taylor admitted to what he did for the BSC via his contact with Sherwood, in his autobiography, Awakening from History (1971): "The propaganda wing, called the Foreign Information Service, was to be headed by Robert E. Sherwood, the noted playwright and one of President Roosevelt's most talented speech writers. I knew Sherwood slightly, from some of the overlapping interventionist committees with which we were both connected, and admired him greatly."

Harriet Hyman Alonso, points out in Robert E. Sherwood The Playwright in Peace and War (2007): "For the next four and a half years, Hopkins, Rosenman, and Sherwood worked as collaboratively as the five writers of the Playwrights' Company. Hopkins, who acted as Roosevelt's liaison on many European trips, worked on fewer speeches, Bob and Rosenman on more. It was Hopkins who usually approached Roosevelt initially, the one who lobbied for those words and proposals which the three thought most important; but Bob and Rosenman sat in on many sessions in which Roosevelt pondered world history and current events, discussing, debating, and generally working through the ideas which they then formed into a speech. Sometimes a speech needed to be drafted out in a short period of time; on other occasions the team worked for a week or more, planning, reworking drafts, consulting with Roosevelt, and rewriting again."

President Franklin D. Roosevelt told Earnest Brandenburg: "In preparing a speech I usually take the various office drafts and suggestions which have been submitted to me and also the material which has been accumulated in the speech file on various subjects, read them carefully, lay them aside, and then dictate my own draft... Naturally, the final speech will contain some of the thoughts and even some of the sentences which appeared in some drafts or suggestions submitted." Sherwood later pointed out: "The collaboration between the three of us and the President was so close and so constant that we generally ended up unable to say specifically who had been primarily responsible for any given sentence or phrase."

Roosevelt, Sherwood and Rosenman worked together on the speech delivered by the president on 28th October, 1940, in New York City. It included the passage: "I have said this before, but I shall say it again and again and again: Your boys are not going to be sent into any foreign wars. They are going into training to form a force so strong that, by its very existence, it will keep the threat of war far away from our shores. The purpose of our defense is defense." Sherwood later commented that "I burn inwardly whenever I think of those words: again and again and again."

Sherwood's close relationship with President Roosevelt resulted in the FBI carrying out an investigation into his politics. This included interviewing his friends. Harold Ross told the agent who contacted him: "Investigate Sherwood? You might as well investigate the American flag." Elmer Rice told the agent who interviewed him: "If you want more information I suggest you try the White House, because Sherwood is living there now, helping the President write his speeches." Rice said that in response to this the agent "nodded gravely".

Sherwood also worked very closely with William Donovan, Roosevelt's Coordinator of Information and the man working closely with William Stephenson. On 16th June, 1941, Sherwood wrote to Donovan and sent him a list of journalists who they could work with in their propaganda campaign. This included Edgar Ansel Mowrer, Raymond Gram Swing, Hubert R. Knickerbocker and Edmond Taylor. Donovan eventually appointed Sherwood as head of the Foreign Information Service. His sister joked that he was the American Joseph Goebbels. He told Harry Hopkins: "Ever since I started the job I am now doing. I have gone on the following basis: that all U.S. information to the world should be considered as though it was a continuous speech by the President."

In January 1945, President Franklin D. Roosevelt sent Sherwood to the Philippines to meet General Douglas MacArthur. His letter of introduction described Sherwood as "my old friend" who was "largely responsible for the organization of our psychological warfare activities in this war." Roosevelt added that the purpose of Sherwood's visit was to "bring home to the American people, and to the peoples of Allied Nations, the vital importance of the continued operations in the war against Japan." The two men got on very well and when Sherwood returned he told Roosevelt that MacArthur was the ideal choice for military governor of Japan.

After the war Sherwood was asked by Samuel Goldwyn and William Wyler to write a film script based on a article written by MacKinlay Kantor about readjustment problems facing a group of marines returning from the war. Goldwyn said this was a great idea for a film: "Returning soldiers! Every family in America is part of this story. When they come home, what do they find? They don't remember their wives, they've never seen their babies, some are wounded - they have to readjust."

Sherwood submitted a script, The Best Year of Our Lives, that he insisted should not be edited. Despite protests from the Production Code Administration, Wyler agreed and they ended up with a film that was two hours and forty-eight minutes long. Sherwood joked: "If it is a success, it will be a formidable blow against the menace of the double-feature - for the picture is so long... that it will be difficult for an exhibitor to crowd another feature into the same program." The film reflected Sherwood's desire for a period of domestic and international peace. General Omar Bradley agreed and said the film would be a great aid to building an "even better democracy".

The Best Year of Our Lives was a great commercial success and became the highest-grossing film in both the United States and UK since the release of Gone with the Wind. A joint telegram from Hedda Hopper, Ethel Barrymore, Cole Porter, George Cukor and Gregory Ratoff claimed: "This is the American motion picture at its best and Sherwood at his best." It also won seven Academy Awards in 1946, including Sherwood for Best Adapted Screenplay. Other awards included Best Picture, Best Director (William Wyler), Best Actor (Fredric March), Best Supporting Actor (Harold Russell), Best Film Editing (Daniel Mandell) and Best Original Score (Hugo Friedhofer).

Sherwood decided to write a book about his two dead friends, Franklin D. Roosevelt and Harry Hopkins. It was also an account of the two men's role in the New Deal. In 1948 Sherwood published Roosevelt and Hopkins: An Intimate History. Reviews were generally good and although he thought it was too long (nearly a 1,000 pages) Archibald MacLeish pointed out: "As a biography, it is too much like a history; and as a history; it is too much like a biography. Its documentation overwhelms the narrative. But.... it will be true that Sherwood's book is not only one of the important books of the last decade but one of the few books of which it can be said with certainty that it is essential to an understanding of the time." The book was number one on the national best-seller list for nearly two months.

Sherwood was a strong anti-communist after the war but he continued to argue for a tolerant attitude towards those with those with different political views. "That we are in a struggle with all the forces of ignorance and fear, of tyranny and poverty and disease, physical and spiritual, that make war possible." For a while he was an advocate of world government and supported the work of the United World Federalists.

On 9th February, 1950, at a meeting of the Republican Women's Club in Wheeling, West Virginia, Joseph McCarthy claimed that he had a list of 205 people in the State Department that were known to be members of the American Communist Party (later he reduced this figure to 57). McCarthy went on to argue that some of these people were passing secret information to the Soviet Union. He added: "The reason why we find ourselves in a position of impotency is not because the enemy has sent men to invade our shores, but rather because of the traitorous actions of those who have had all the benefits that the wealthiest nation on earth has had to offer - the finest homes, the finest college educations, and the finest jobs in Government we can give."

Sherwood was appalled by this approach to politics. His close friend Elmer Rice suffered from McCarthyism and was condemned for being on the board of directors of the American Civil Liberties Union and for signing a congratulatory telegram to the Moscow Art Theatre on its fiftieth anniversary. Other friends, such as John Paton Davis and Edward Corsi were sacked by secretary of state John Foster Dulles, for holding what was considered to be left-wing views. Sherwood wrote a letter of protest to President Dwight Eisenhower: "Just when did we resolve that the rights of the individual American citizen should be subordinated and indeed destroyed by some undocumented interpretation of some official tells us is national security".

Sherwood continued to write but in the 1950s he began to suffer from a variety of ailments. In September, 1955 he was admitted to John Hopkins Hospital where they considered operating on him to relieve the constant headaches he was experiencing. On 11th November, he wrote in his diary: "Have many ideas, but the minute I try to work, I feel dead."

Robert Emmet Sherwood died of a heart attack in New York City on 14th November 1955.

Primary Sources

(1) Harriet Hyman Alonso, Robert E. Sherwood The Playwright in Peace and War (2007)

Life in Arras and on Vimy Ridge was difficult, to say the least. Trench life, in particular, was one of the most wearying experiences of the war. The physical conditions alone were very hard. Thousands of men were packed together for weeks and months at a time in what were basically narrow gullies without permanent tops. Interconnecting branches led to sections where officers might have makeshift quarters, supplies could be kept, and the injured might be cared for. Men in the trenches were exposed to all of nature's wrath - rain, snow, cold, fog, and intense sun. Day and night they lived outdoors, the only relief being provided by cave-like dugouts where they took breaks to sleep, eat, play poker, and tell stories of their trysts with Frenchwomen while on leave in Paris. At its best, trench life was excruciatingly boring as soldiers waited for their next foray into enemy territory or the enemy's into theirs. At worst, it was wet, muddy, and constantly damp. Death could come quickly from illness, a sniper's good shot, a poison gas shelling, or an attack, and corpses could not always be removed immediately.

(2) Robert E. Sherwood, Roosevelt and Hopkins: An Intimate History (1948)

Six months before the United States entered the war... there was, by Roosevelt's order and despite State Department qualms, effectively close cooperation between J. Edgar Hoover and the FBI and British security services under the direction of the quiet Canadian, William Stephenson... If the isolationists had known the full extent of the secret alliance between the U.S. and Britain, their demands for the President's impeachment would have rumbled like thunder across the land.

(3) Robert E. Sherwood, Roosevelt and Hopkins: An Intimate History (1948)

I wished him (Roosevelt) a happy holiday in Warm Springs, then went down to the Cabinet Room-where Hopkins, Rosenman and I had worked so many long hours - and I wrote the memorandum on MacArthur, then walked to the Carlton Hotel and told my wife that the President was in much worse shape than I had ever seen him before. He had seemed unnaturally quiet and even querulous - never before had I found myself in the strange position of carrying on most of the conversation with him; and, while he had perked up a little at lunch under the sparkling influence of his daughter Anna, I had come away from the White House profoundly depressed. I thought it was a blessing that he could get away for a while to Warm Springs, and I was sure the trip across the country to San Francisco would do him a lot of good. The thought never occurred to me that this time he might fail to rally as he always had. I couldn't believe it when somebody told me he was dead. Like everybody else, I listened and listened to the radio, waiting for the announcement - probably in his own gaily reassuring voice - that it had all been a big mistake, that the banking crisis and the war were over and everything was going to be "fine-grand perfectly bully." But when the realization finally did get through all I could think of was, "It finally crushed him. He couldn't stand up under it any longer." The "it" was the awful responsibility that had been piling up and piling tip for so many years. The fears and the hopes of hundreds of millions of human beings throughout the world had been hearing down on the mind of one man, until the pressure was more than mortal tissue could withstand, and then he said, "I have a terrific headache," and then lost consciousness, and died. "A massive cerebral hemorrhage," said the doctors - and "massive" was the right word.

The morning after Roosevelt's death Hopkins telephoned me from St. Mary's Hospital in Rochester, Minnesota. He just wanted to talk to somebody. There was no sadness in his tone; he talked with a kind of exaltation as though he had suddenly experienced the intimations of immortality. He said, "You and I have got something great that we can take with us all the rest of our lives. It's a great realization. Because we know it's true what so many people believed about him and what made them love him. The President never let them down. That's what you and I can remember. Oh, we all know he could be exasperating, and he could seem to be temporizing and delaying, and he'd get us all worked tip when we thought he was making too many concessions to expediency. But all of that was in the little things, the unimportant things - and he knew exactly how the little and how unimportant they really were. But in the big things - all of the things that were of real, permanent importance - he never let the people down."

(4) Robert E. Sherwood, Roosevelt and Hopkins: An Intimate History (1948)

There was a curious and revelatory episode in which I happened to he involved on the Sunday when Hitler invaded the Soviet Union. I was scheduled to attend a Fight for Freedom rally in the Golden Gate Ballroom in Harlem. It was an insufferably hot day and there was no pretense at air conditioning in the ballroom. When we went in there was a picket line outside (obviously a Communist one) with placards condemning Fight for Freedom warmongers as tools of British and Wall Street Imperialism. Pamphlets were being handed out urging a Negro March on Washington to demand Equality and Peace! The

Communists were very active among the Negro population in these days and since. We went through the picket line and conducted the meeting, the principal speakers being Herbert Agar and Dorothy Parker, and when we left the Golden Gate Ballroom, an hour and a half later, we found that the picket line had disappeared and the March on Washington had been canceled. Within that short space of time, the Communist party line had reached all the way from Moscow to Harlem and had completely reversed itself (or rather, had been completely reversed by Hitler). The next day, the Daily Worker was pro-British, pro-Lend Lease, pro-interventionist and, for the first time in two years, pro-Roosevelt.

(5) Elmer Davis, broadcasting on CBS (January, 1942)

There are some patriotic citizens who sincerely hope that America will win the war - but they also hope that Russia will lose it; and there are some who hope that America will win the war, but that England will lose it; and there are some who hope that America will win the war, but that Roosevelt will lose it!