Franklin Pierce Adams

Franklin Pierce Adams, the son of Moses and Clara Schlossberg Adams, was born in Chicago, Illinois, on 15th November, 1881. Adams graduated from the Armour Scientific Academy in 1899, attended the University of Michigan before leaving to work in insurance.

Adams began working for the Chicago Evening Journal in 1903. At first he was a sports writer but he also wrote a column where he could express his great sense of humor. In 1904 he moved to the New York Evening Mail to write a column, Always in Good Humor . It was a great success and according to Howard Teichmann "it contained little bits about many things, but each seemed to be a highly polished jewel, each a gem of fashionable prose or poetry." Adams encouraged readers to send in contributions. During this period contributors included Edna St. Vincent Millay, Sinclair Lewis, Dorothy Parker, Edna Ferber, Alice Duer Miller, Deems Taylor and Ring Lardner.

Adams also accepted material from a young ribbon salesman, George S. Kaufman. In 1908 he arranged to meet Kaufman. The author of George S. Kaufman: An Intimate Portrait (1972) points out: "When they met it was as if everything in Adams was exaggerated in Kaufman. Adams was thin, Kaufman was skinny. Adams' complexion was pale, Kaufman's was sallow. Kaufman's nose was bigger than Adams', his eyeglasses were thicker, his hair blacker and bushier. Adams was five feet eight inches in height; Kaufman stood over six feet... Adams was a man. Kaufman was an eighteen-year-old boy."

In 1911, he added a second column, a parody of Samuel Pepys's Diary, with notes drawn from his personal experiences. For example, he reported on the engagement of his friend, Heywood Broun and Lydia Lopokova. "Heywood Broun, the critic, I hear hath become engaged to Mistress Lydia Lopokova, the pretty play actress and dancer. He did introduce her to me last night and she seemed a merry elf."

In 1914, he moved his column to the New York Tribune, where it was retitled The Conning Tower . According to John Keats, the author of You Might as Well Live: The Life and Times of Dorothy Parker (1971): "Adams, an erudite and witty man who greatley resembled a narrow-shouldered moose, had before the war edited the city's most widely read and literate newspaper column."

During the First World War Adams served in military intelligence. He was later assigned to the recently established Stars and Stripes, a weekly newspaper by enlisted men for enlisted men. Harold Ross was the editor and others working on the newspaper included Alexander Woollcott, Cyrus Leroy Baldridge, Grantland Rice, Adolf Shelby Ochs, Stephen Early and Guy Viskniskki. Adams main contribution was a column entitled The Listening Post .

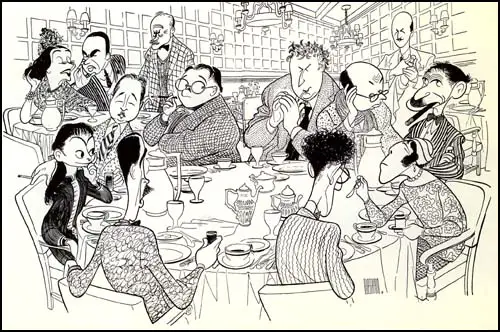

After the war he returned to the New York Tribune. During this period he became associated with a group who had lunch together in the dining room at the Algonquin Hotel. This group eventually became known as the Algonquin Round Table and included Robert E. Sherwood, Dorothy Parker, Robert Benchley, Alexander Woollcott, Heywood Broun, Harold Ross, Donald Ogden Stewart, Edna Ferber, Ruth Hale, Jane Grant, Neysa McMein, Alice Duer Miller, Charles MacArthur, Marc Connelly, George S. Kaufman, Beatrice Kaufman , Frank Crowninshield, Ben Hecht, John Peter Toohey, Lynn Fontanne, Alfred Lunt and Ina Claire.

Samuel Hopkins Adams, the author of Alexander Woollcott: His Life and His World (1946), has argued: "The Algonquin profited mightily by the literary atmosphere, and Frank Case evinced his gratitude by fitting out a workroom where Broun could hammer out his copy and Benchley could change into the dinner coat which he ceremonially wore to all openings. Woollcott and Franklin Pierce Adams enjoyed transient rights to these quarters. Later Case set aside a poker room for the whole membership." The poker players included Adams, Alexander Woollcott, Herbert Bayard Swope, Robert Benchley, Harold Ross, Heywood Broun, George S. Kaufman, Deems Taylor, Laurence Stallings, Harpo Marx, Jerome Kern and Prince Antoine Bibesco. On one occasion, Woollcott lost four thousand dollars in an evening, and protested: "My doctor says it's bad for my nerves to lose so much." It was also claimed that Harpo Marx "won thirty thousand dollars between dinner and dawn". Howard Teichmann, the author of George S. Kaufman: An Intimate Portrait (1972) has argued that Broun, Adams, Benchley, Ross and Woollcott were all inferior poker players, Swope and Marx were rated as "pretty good" and Kaufmann was "the best honest poker player in town."

By this time Franklin Pierce Adams was famous. Brian Gallagher, the author of Anything Goes: The Jazz Age of Neysa McMein and her Extravagant Circle of Friends (1987) has argued: " In the column, Adams combined pungent observations on contemporary trends and events - he was the grandfather, or perhaps great grandfather, of The New Yorker style of humor - with the contributions, chiefly light verse and apercus, sent him by a willing, talented, and unpaid group of aspiring writers. Quaint and creaky as it now reads, the column did set new standards, in American humor (legitimizing puns, for one thing) and helped start the career of any number of writers.... If FPA was, as several commentators have noted, more of a conductor than a writer, it was true that he beat a quick, light, and, for the time, witty tempo. By 1920 FPA was the best-known set of non-presidential initials in the country."

In 1921 Ruth Hale, established the Lucy Stone League. The first list of members included only fifty names. This included Adams, Heywood Broun, Jane Grant, Neysa McMein, Beatrice Kaufman , Anita Loos, Zona Gale, Janet Flanner and Fannie Hurst. Its principles were forcefully expressed in a booklet written by Hale: "We are repeatedly asked why we resent taking one man's name instead of another's why, in other words, we object to taking a husband's name, when all we have anyhow is a father's name. Perhaps the shortest answer to that is that in the time since it was our father's name it has become our own that between birth and marriage a human being has grown up, with all the emotions, thoughts, activities, etc., of any new person. Sometimes it is helpful to reserve an image we have too long looked on, as a painter might turn his canvas to a mirror to catch, by a new alignment, faults he might have overlooked from growing used to them. What would any man answer if told that he should change his name when he married, because his original name was, after all, only his father's? Even aside from the fact that I am more truly described by the name of my father, whose flesh and blood I am, than I would be by that of my husband, who is merely a co-worker with me however loving in a certain social enterprise, am I myself not to be counted for anything."

In 1922, Herbert Bayard Swope, the editor of the New York World, invited Adams to work for his newspaper. Swope had recruited a significant number of columnists, most of them on a three-times-a-week basis. This included Alexander Woollcott , William Bolitho , Heywood Broun, Deems Taylor, Samuel Chotzinoff, Laurence Stallings, Harry Hansen and St. John Greer Ervine. Swope's biographer, Ely Jacques Kahn, has argued: "Its contributors were encouraged by Swope, who never wrote a line for it himself, to say whatever they liked, restricted only by the laws of libel and the dictates of taste. To keep their stuff from sounding stale, moreover, he refused to build up a bank of ready-to-print columns; everybody wrote his copy for the following day's paper." It has been argued by Howard Teichmann that during this period Adams established himself as "America's finest humor columnist".

Adams had fond memories of working at the newspaper: "Never had I known such fun in a newspaper office as I had the first few years on the New York World. Whatever office politics there may have been, I was unaffected, for nobody wanted my job and I didn't want anybody's... Often there were discussions and violent, abusive argumments lasting three hours... There were fights - generally by telephone - with my technical boss, Mr. Swope... who never changed a line, in or out, of mine, except once, when he saved me, by changing something that had become untrue between the time that I wrote it, at 3 p.m., and 8:30 p.m."

Adams became a close friend of Heywood Broun during this period: "Broun was a debunker of any kind of pretentiousness, political, official, or literary... He hated injustice and intolerance; seldom did he dislike those he considered unjust or intolerant. He was a lion in print, but a lamb in his personal relationships. Men whom he attacked in print would invite him to lunch; he'd go, and the victim of his wrath would fall to his charm. Heywood, for twenty years or so, must have earned lots of money. He cared less for money than anyone I knew."

F. D. White was the business manager of the New York World. He disapproved of the progressive views expressed by people like Adams, Broun and Laurence Stallings. He had a deep loathing of what he considered to be their radical ideas. White proclaimed that these "ideas of liberalism... are playing hell with the interest of the paper". He suggested that if Ralph Pulitzer was so determined to take part in this "liberal crusade" he should "subsidize another newspaper and let Broun, Stallings, Adams and other agitators... run riot on its pages".

In May 1928 Heywood Broun was sacked after writing an article supporting birth-control. Adams was responsible for trying to replace Broun, has argued: "Dozens of pinch-hitters, substitutes, and more or less permanencies did their three-a-week best... I took a shot at getting people to write for it during the summer of 1930, and people on the staff always gave it to me for the Broun column. I want it on the record that firing Broun, for anything, was a mistake."

In December 1930 Ralph Pulitzer began negotiating with Roy W. Howard about the selling of the New York World. The sale went through and the last edition of the newspaper was published on 27th February, 1931. The Scripps-Howard organization now merged the two newspapers and gave it the name the New York World-Telegram . Adams became one of its main contributors. In 1937 he moved to the New York Post.

In 1938 Adams became a a panelist on radio's Information Please. The idea of the show was that panelists would attempt to answer questions submitted by listeners. The listener was paid five dollars for a question that was used, and ten dollars more if the experts could not answer it correctly. The show was as much a comedy as a quiz show and the panelists were expected to provide funny answers to the questions. Adams was also on the panel when it became a television program in 1952.

Franklin Pierce Adams died in New York City on 23rd March, 1960.

© John Simkin, May 2013

Primary Sources

(1) Howard Teichmann, George S. Kaufman: An Intimate Portrait (1972)

Franklin Pierce Adams was a Chicago boy not unlike George S. Kaufman in appearance, family background, and mental agility. His first job was in 1903 with the Chicago Journal, where he wrote a daily weather story. Later he was allowed the luxury of a daily humor column. Although everyone is interested in the weather, Adams' humor column became so successful that he was granted permission to concentrate on it alone. But Adams refused to monopolize the humor column. Instead, he invited contributions from his readers. These poured in like rain in the spring on Lake Michigan. After a year and an increase in salary, Adams was ready for the East.

New York took him and turned him into what New York can do quicker than any other city in the world. It made F.P.A. a celebrity. Now his contributors were Edna St. Vincent Millay, Sinclair Lewis, Dorothy Parker, Ring Lardner, Edna Ferber, Deems Taylor, John Erskine, Alice Duer Miller-in short, the brightest young names in American letters.

It seemed unusual, therefore, that in 1908 witticisms should start coming in from Paterson, New Jersey. Moreover, they were not the usual bumpkin-like banalities. They were good, and Adams began to run them. The Paterson contributor, taking his cue from Adams' own nom de plume, signed himself G.S.K.

To see his own words in print in a New York newspaper did for George S. Kaufman what the switch does for the electric light bulb. He exploded entire barrages of comments, jokes, puns, witticisms across the river to F.P.A. As a reward, F.P.A. used more and more by G.S.K. Finally, he was invited into New York to dine with the great columnist.When they met it was as if everything in Adams was exaggerated in Kaufman. Adams was thin, Kaufman was skinny. Adams' complexion was pale, Kaufman's was sallow. Kaufman's nose was bigger than Adams', his eyeglasses were thicker, his hair blacker and bushier. Adams was five feet eight inches in height; Kaufman stood over six feet.

(2) Brian Gallagher, Anything Goes: The Jazz Age of Neysa McMein and her Extravagant Circle of Friends (1987)

Franklin Pierce Adams was, like Neysa, a Midwesterner (from Chicago in his case) who had come to New York in search of a smarter, more sophisticated life. Born in 1881, he had moved to New York in 1903 and had immediately begun to establish himself as a newspaperman. By 1909 he was well enough known to collaborate with O. Henry - on a quickly forgotten musical, Lo! - and by 1911 he had created, for the New York Evening Mail, his "Always in a Good Humor" column, which he renamed "The Conning Tower" when he moved it to the Tribune in 1914. From the first, the column was a forcing house for the kind of witty sophistication FPA had come to New York seeking and was now helping to define and exemplify.

In the column, Adams combined pungent observations on contemporary trends and events - he was the grandfather, or perhaps great grandfather, of The New Yorker style of humor - with the contributions, chiefly light verse and apercus, sent him by a willing, talented, and unpaid group of aspiring writers. Quaint and creaky as it now reads, the column did set new standards, in American humor (legitimizing puns, for one thing) and helped start the career of any number of writers. Dorothy Parker's witty bow in FPA's direction - "he raised me from a couplet" - could have been made by a number of other writers who came to sit beside this "homely little man" at the Round Table in the decade following their first appearance in his column: Marc Connelly, Robert Benchley, George S. Kaufman (who invented the "S" as a means, he thought, of giving added distinction to his contributions to FPA's column). If FPA was, as several commentators have noted, more of a conductor than a writer, it was true that he beat a quick, light, and, for the time, witty tempo. By 1920. "FPA" was the best-known set of non-presidential initials in the country.

FPA enjoyed a reputation as, in the words of one of his contemporaries, "a facile artistic talent, a quick wit, and a brilliant personality." Nothing fostered this impression so much as his weekly chronicle, in what now seems excruciating detail and unbearable mock-Restoration prose (Samuel Pepys's diary was his ostensible model), of his hourly doings as a social and theatrical gadabout on the metropolitan scene. To be a regular "character" in that chronicle was to be assured a certain vaguely mythic notoriety. Neysa now felt herself ready to assume that role.

Putting aside whatever superstitious misgivings she had, Neysa, bearing a nosegay of sweet peas, descended on FPA at his Tribune office on Friday, April 13, 1917. FPA could be easily swayed ("Compared with me, a weather vane is Gibraltar"), and swayed by Neysa he was. For the afternoon, these two transplanted Midwesterners "talked of Quincy and Chicago and Literature and the war." Even then, Adams felt "regretfull that she went away so soon." Although she might not have realized it at the time, Neysa had made the essential contact that would determine the shape of her life for the next decade - and beyond.

In the following weeks, Neysa appeared regularly in FPA's record of his doings. He visits her apartment, reports she is ill, dines with her, takes her to the Lambs' Gambol (where both find a rising humorist, Will Rogers, the best of the evening's entertainment), and escorts her to a lecture by an Arctic explorer (where only Neysa finds the penguins accompanying it amusing). "Mistress Neysa" is pictured "very fair in a blue dress"; after a separation of some months, FPA reports "her charm no less than ever."

Over the first years of their acquaintance, FPA was discovering what he would later characterize as Neysa's chief, if most curious, attraction-namely, that her ignorance of certain things could be more enlightening than other people's knowledge of them. No doubt he, and many another man, took a witty pleasure in informing her.

Neysa, for her part, took to being informed very gracefully, for she was a good listener, though hardly a passive or uncritical one. Those men, and occasionally women, who undertook the informal task of educating her had to be up to the mark themselves. Despite a willed casualness and vagueness, Neysa also maintained a stubbornly realistic streak that allowed her to separate sense from nonsense.