The National Health Service Act

After the 1945 General Election, Clement Attlee, the new Labour Prime Minister, appointed Aneurin Bevan as Minister of Health. According to John Campbell, the author of Nye Bevan and the Mirage of British Socialism (1987) it was "a remarkable appointment for Attlee to bring Bevan straight into the Cabinet as Minister of Health - by far the boldest stroke in a generally cautious exercise in rewarding the long-serving party faithful." At forty-seven Bevan was by some years the youngest member of a Cabinet whose average age was over sixty." (1)

In 1946 Parliament passed the revolutionary National Insurance Act. It instituted a comprehensive state health service, effective from 5th July 1948. The Act provided for compulsory contributions for unemployment, sickness, maternity and widows' benefits and old age pensions from employers and employees, with the government funding the balance. It promised an all-embracing social insurance scheme from the "cradle to the grave", a system which would give people benefits as of right, and without a means test. (2)

The government announced plans for a National Health Service that would be, "free to all who want to use it." The legislation established "a comprehensive health service designed to secure improvement in the physical and mental health of the people of England and Wales and the prevention, diagnosis and treatment of illness and for that purpose to provide or secure the effect of provision of services." It passed by 359 votes to 172. (3)

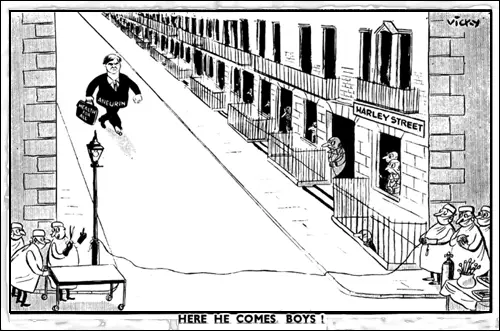

Some members of the medical profession opposed the government's plans. Between 1946 and its introduction in 1948, the British Medical Association (BMA) mounted a vigorous campaign against this proposed legislation. In one survey of doctors carried out in 1948, the BMA claimed that only 4,734 doctors out of the 45,148 polled, were in favour of a National Health Service. The main complaint of the BMA was that the NHS would "turn doctors from free-thinking professionals into salaried servants of central government". At a BMA a doctor was "cheered to the rooftops" when he said the NHS was "strongly suggestive of the Hitlerite regime" in Nazi Germany. (4)

Opposition to National Health Service

The right-wing national press was opposed to the idea of a National Health Service. The Daily Sketch reported: "The State medical service is part of the Socialist plot to convert Great Britain into a National Socialist economy. The doctors' stand is the first effective revolt of the professional classes against Socialist tyranny. There is nothing that Bevan or any other Socialist can do about it in the shape of Hitlerian coercion." (5)

Winston Churchill led the attack on Aneurin Bevan. In one debate in the House of Commons he argued that unless Bevan "changes his policy and methods and moves without the slightest delay, he will be as great a curse to his country in time of peace as he was a squalid nuisance in time of war." The Conservative Party voted against the measure. The Tory ammendment stated that it "declines to give a Third Reading to a Bill which discourages voluntary effort and association; mutilates the structure of local government; dangerously increases minisaterial power and patronage; approppriates trust funds and benefactions in contempt of the wishes of donors and subscribers; and undermines the freedom and independence of the medical profession to the detriment of the nation." (6) However, on 2th July, 1946, the Third Reading was carried by 261 votes to 113. Michael Foot commented that the Conservatives had voted against the "most exciting and popular of the Government's measures a bare four months before it was to be introduced". (7)

David Widgery, the author of The National Health: A Radical Perspective (1988) admitted that "the Act was bold in outline; a National Health Service entirely free at the time of use, financed out of general taxation and able to organise preventive medicine, research and paramedical aids on a national basis... Bevan himself was apparently well prepared to deal with conservative pressures, and he was quite prepared for the out-break of near-hysteria by doctors, skilfully orchestrated by Charles Hill of the BMA, who had endeared himself to the listening public during the war as the smooth-spoken, concerned Radio Doctor." (8)

Between 1946 and its introduction in 1948, the British Medical Association (BMA), led by Charles Hill, mounted a vigorous campaign against this proposed legislation. In one survey of doctors carried out in 1948, the BMA claimed that only 4,734 doctors out of the 45,148 polled, were in favour of a National Health Service. One doctor was cheered at a BMA meeting for saying that the proposed NHS bill was "strongly suggestive" of what had been going in Nazi Germany. (9)

National Health Service Act

By July 1948, Aneurin Bevan had guided the National Health Service Act safely through Parliament. The Government resolution was carried by 337 votes to 178. Niall Dickson has pointed out: "The UK's National Health Service (NHS) came into operation at midnight on the fourth of July 1948. It was the first time anywhere in the world that completely free healthcare was made available on the basis of citizenship rather than the payment of fees or insurance premiums... Life in Britain in the 30s and 40s was tough. Every year, thousands died of infectious diseases like pneumonia, meningitis, tuberculosis, diphtheria, and polio. Infant mortality - deaths of children before their first birthday - was around one in 20, and there was little the piecemeal healthcare system of the day could do to improve matters. Against such a background, it is difficult to overstate the impact of the introduction of the National Health Service (NHS). Although medical science was still at a basic stage, the NHS for the first time provided decent healthcare for all - and, at a stroke, transformed the lives of millions." (10)

The Manchester Guardian commented on the passing of the National Health Service Act: "These two reforms have sometimes been greeted as a large installment of Socialism in this country. They are not strictly that, for many besides Socialists have contributed something to them. What they mark is rather an advance of the equalitarianism which has been the mainspring, though not the exclusive possession, of the British Labour movement. They are designed to offset as far as they can the inequalities that arise from the chances of life, to ensure that a "bad start" or a stroke of bad luck, illness or accident or loss of work, does not carry the heavy, often crippling, economic penalty it has carried in the past. It is important to realise the fundamental change in attitude which this implies, and its consequences for our social evolution." (11)

In October 1950, Clement Attlee promoted Hugh Gaitskell to chancellor of the exchequer. Aneurin Bevan considered Gaitskell as hostile to the National Health Service and sent a letter to Attlee commenting: "I feel bound to tell you that for my part I think the appointment of Gaitskell to be a great mistake. I should have thought myself that it was essential to find out whether the holder of this great office would commend himself to the main elements and currents of opinion in the Party. After all, the policies which he will have to propound and carry out are bound to have the most profound and important repercussions throughout the movement." (12)

One of Gaitskell's first tasks was to balance the budget. The National Insurance Act created the structure of the Welfare State and after the passing of the National Health Service Act in 1948, people in Britain were provided with free diagnosis and treatment of illness, at home or in hospital, as well as dental and ophthalmic services. Michael Foot, the author of Aneurin Bevan (1973) has argued: "On the afternoon of 10th April he (Hugh Gaitskell) presented his Budget, including the proposal to save £13 million - £30 million in a full year-by imposing charges on spectacles and on dentures supplied under the Health Service. And glancing over his shoulder at the benches behind him he had seemed to underline his resolve: having made up his mind, he said, a Chancellor 'should stick to it and not be moved by pressure of any kind, however insidious or well-intentioned'. Bevan did not take his accustomed seat on the Treasury bench, but listened to this part of the speech from behind the Speaker's chair, with Jennie Bevan by his side. A muffled cry of 'shame' from her was the only hostile demonstration Gaitskell received that afternoon." (13)

Resignation of Aneurin Bevan

The following day, Aneurin Bevan resigned from the government. In a speech he made in the House of Commons he explained why he had made this decision: "The Chancellor of the Exchequer in this year's Budget proposes to reduce the Health expenditure by £13 million - only £13 million out of £4,000 million... If he finds it necessary to mutilate, or begin to mutilate, the Health Services for £13 million out of £4,000 million, what will he do next year? Or are you next year going to take your stand on the upper denture? The lower half apparently does not matter, but the top half is sacrosanct. Is that right?... The Chancellor of the Exchequer is putting a financial ceiling on the Health Service. With rising prices the Health Service is squeezed between that artificial figure and rising prices. What is to be squeezed out next year? Is it the upper half? When that has been squeezed out and the same principle holds good, what do you squeeze out the year after? Prescriptions? Hospital charges? Where do you stop?"

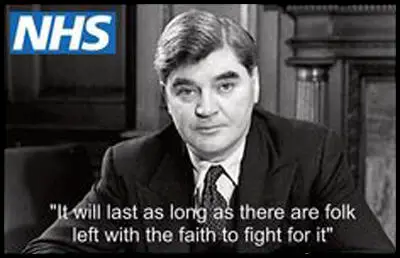

Aneurin Bevan went on to argue that this measure was undermining the Welfare State: " Friends, where are they going? Where am I going? I am where I always was. Those who live their lives in mountainous and rugged countries are always afraid of avalanches, and they know that avalanches start with the movement of a very small stone. First, the stone starts on a ridge between two valleys - one valley desolate and the other valley populous. The pebble starts, but nobody bothers about the pebble until it gains way, and soon the whole valley is overwhelmed. That is how the avalanche starts, that is the logic of the present situation, and that is the logic my right honourable friends cannot escape.... After all, the National Health Service was something of which we were all very proud, and even the Opposition were beginning to be proud of it. It only had to last a few more years to become a part of our traditions, and then the traditionalists would have claimed the credit for all of it. Why should we throw it away? In the Chancellor's Speech there was not one word of commendation for the Health Service - not one word. What is responsible for that?" (14)

Primary Sources

(1) The Daily Sketch (February, 1948)

The State medical service is part of the Socialist plot to convert Great Britain into a National Socialist economy. The doctors' stand is the first effective revolt of the professional classes against Socialist tyranny. There is nothing that Bevan or any other Socialist can do about it in the shape of Hitlerian coercion.

(2) Aneurin Bevan, speech in the House of Commons (9th February, 1948)

We have provided paid bed blocks to specialists, where they are able to charge private fees (Labour MPs shout "shame"). I agree at once that these are very serious things, and that, unless properly controlled, we can have a two-tier system in which it will be thought that members to the general public will be having worse treatment than those who are able to pay.

(3) Michael Foot, the editor of Tribune, was one of those who criticised Aneurin Bevan for his decision to allow specialists to have paid beds in National Health Service hospitals.

The idea that specialists should have pay-beds was a concession. It was a direct departure from principle introduced only for the purpose of encouraging specialists to come into the Service and preventing them from setting up their private nursing homes.

So the great day came - 5th July 1948. On the day itself three-quarters of the population had signed up with doctors under the scheme. Two months later, 39,500,000 people, or 93 per cent were enrolled in it. More than 20,000 general practitioners, about 90 per cent, participated from the scheme's inception.

(4) The Manchester Guardian (5th July, 1948)

The new system of social security, under the Ministry of National Insurance, also comes into operation to-day. The impact of this, unlike that of the National Health Service, will make itself felt at once; to many people in the disagreeable form of a higher rate of weekly insurance contributions, to others by a demand for contributions previously not paid at all. Most of the benefits will not be experienced until the need for them arises; and many people will wait long enough for that. Yet it too is a great step forward. One recalls the surge of enthusiasm with which the Beveridge Report was greeted. To millions of people below the "salaried job" level security is almost as tangible a thing as money itself; to know that bad luck will not mean acute poverty is to be free of the most persistent and stabbing anxiety which afflicts the wage-earner.

After these years of full employment that anxiety has perhaps lost some of its sting. But the nineteen-thirties are still near enough to be remembered with fear and bitterness, and with gratitude for the day on which Mr. Arthur Greenwood appointed Lord Beveridge to review the existing provisions for social insurance and to recommend plans for filling the gaps. The new security system which has grown out of this decision is on a tremendous scale.

These two reforms have sometimes been greeted as a large installment of Socialism in this country. They are not strictly that, for many besides Socialists have contributed something to them. What they mark is rather an advance of the equalitarianism which has been the mainspring, though not the exclusive possession, of the British Labour movement. They are designed to offset as far as they can the inequalities that arise from the chances of life, to ensure that a "bad start" or a stroke of bad luck, illness or accident or loss of work, does not carry the heavy, often crippling, economic penalty it has carried in the past. It is important to realise the fundamental change in attitude which this implies, and its consequences for our social evolution.

Mr. Churchill has, with his usual frankness and pith, defined the main process by which the powerful structure of our industrial society has been built up as "competitive selection." That process requires a sump, a bottom level to which the weakest and least fit are thrust down beyond the point of survival, or at least of reproduction. For a century we have been tending away from the logical application of this principle, and neither Mr. Churchill nor any other humane man would wish to see it whole-heartedly applied again to-day.

(5) Niall Dickson, BBC News (1st July, 1998)

The UK's National Health Service (NHS) came into operation at midnight on the fourth of July 1948. It was the first time anywhere in the world that completely free healthcare was made available on the basis of citizenship rather than the payment of fees or insurance premiums. The service has been beset with problems throughout its lifetime, not least a continuing shortage of cash. But having cared for the nation for half a century, most Britons consider the NHS to have been an outstanding success.

Only 50 years ago, health care was a luxury not everyone could afford.

Life in Britain in the 30s and 40s was tough. Every year, thousands died of infectious diseases like pneumonia, meningitis, tuberculosis, diphtheria, and polio.

Infant mortality - deaths of children before their first birthday - was around one in 20, and there was little the piecemeal healthcare system of the day could do to improve matters.

Against such a background, it is difficult to overstate the impact of the introduction of the National Health Service (NHS). Although medical science was still at a basic stage, the NHS for the first time provided decent healthcare for all - and, at a stroke, transformed the lives of millions.

(6) Jennie Lee, My Life With Nye (1981)

There was a strict rule in Nye's Ministry that any unsolicited gifts sent to him should be promptly returned. On one occasion, and only one, an exception was made. Nye brought home a letter containing a white silk handkerchief with crochet round the edge. The hanky was for me. The letter was from an elderly Lancashire lady, unmarried, who had worked in the cotton mills from the age of twelve. She was overwhelmed with gratitude for the dentures and reading glasses she had received free of charge. The last sentence in her letter read, "Dear God, reform thy world beginning with me," but the words that hurt most were, "Now I can go into any company." The life-long struggle against poverty which these words revealed is what made all the striving worthwhile.

(7) Aneurin Bevan, letter to Clement Attlee (October, 1950)

I feel bound to tell you that for my part I think the appointment of Gaitskell to be a great mistake. I should have thought myself that it was essential to find out whether the holder of this great office would commend himself to the main elements and currents of opinion in the Party. After all, the policies which he will have to propound and carry out are bound to have the most profound and important repercussions throughout the movement.

(8) Aneurin Bevan, resignation speech (23rd April, 1951)

I now come to the National Health Service side of the matter. Let me say to my hon. Friends on these benches: you have been saying in the last fortnight or three weeks that I have been quarrelling about a triviality - spectacles and dentures. You may call it a triviality. I remember the triviality that started an avalanche in 1931. I remember it very well, and perhaps my hon. Friends would not mind me recounting it. There was a trade union group meeting upstairs. I was a member of it and went along. My good friend, "Geordie" Buchanan, did not come along with me because he thought it was hopeless, and he proved to be a better prophet than I was. But I had more credulity in those days than I have got now. So I went along, and the first subject was an attack on the seasonal workers. That was the first order. I opposed it bitterly, and when I came out of the room my good old friend George Lansbury attacked me for attacking the order. I said, "George, you do not realise, this is the beginning of the end. Once you start this there is no logical stopping point."

The Chancellor of the Exchequer in this year's Budget proposes to reduce the Health expenditure by £13 million - only £13 million out of £4,000 million. No, £4,000 million. He has taken £13 million out of the Budget total of £4,000 million. If he finds it necessary to mutilate, or begin to mutilate, the Health Services for £13 million out of £4,000 million, what will he do next year? Or are you next year going to take your stand on the upper denture? The lower half apparently does not matter, but the top half is sacrosanct...

The Chancellor of the Exchequer is putting a financial ceiling on the Health Service. With rising prices the Health Service is squeezed between that artificial figure and rising prices. What is to be squeezed out next year? Is it the upper half? When that has been squeezed out and the same principle holds good, what do you squeeze out the year after? Prescriptions? Hospital charges? Where do you stop? I have been accused of 42 having agreed to a charge on prescriptions. That shows the danger of compromise. Because if it is pleaded against me that I agreed to the modification of the Health Service, then what will be pleaded against my right hon. Friends next year, and indeed what answer will they have if the vandals opposite come in? What answer? The Health Service will be like Lavinia - all the limbs cut off and eventually her tongue cut out, too...

Friends, where are they going? Where am I going? I am where I always was. Those who live their lives in mountainous and rugged countries are always afraid of avalanches, and they know that avalanches start with the movement of a very small stone. First, the stone starts on a ridge between two valleys - one valley desolate and the other valley populous. The pebble starts, but nobody bothers about the pebble until it gains way, and soon the whole valley is overwhelmed. That is how the avalanche starts, that is the logic of the present situation, and that is the logic my right hon. and hon. Friends cannot escape. Why, therefore, has it been done in this way?

After all, the National Health Service was something of which we were all very proud, and even the Opposition were beginning to be proud of it. It only had to last a few more years to become a part of our traditions, and then the traditionalists would have claimed the credit for all of it. Why should we throw it away? In the Chancellor's Speech there was not one word of commendation for the Health Service - not one word. What is responsible for that?

Why has the cut been made? He cannot say, with an overall surplus of over £220 million and a conventional surplus of £39 million, that he had to have the £13 million. That is the arithmetic of Bedlam. He cannot say that his arithmetic is so precise that he must have the £13 million, when last year the Treasury were £247 million out. Why? Has the A.M.A. succeeded in doing what the B.M.A. failed to do? What is the cause of it? Why has it been done?

I will tell my hon. Friends something else, too. There was another policy - there was a proposed reduction of 25,000 on the housing programme, was there not? It was never made. It was necessary for me at that time to use what everybody always said were bad tactics upon my part - I had to manœuvre, and I did manœuvre and saved the 25,000 houses and the prescription charge. I say, therefore, to my right hon. and hon. Friends, there is no justification for taking this line at all. There is no justification in the arithmetic, there is less justification in the economics, and I beg my right hon. and hon. Friends to change their minds about it.

I say this, in conclusion. There is only one hope for mankind - and that is democratic Socialism. There is only one party in Great Britain which can do it - and that is the Labour Party. But I ask them carefully to consider how far they are polluting the stream. We have gone a long way - a very long way - against great difficulties. Do not let us change direction now. Let us make it clear, quite clear, to the rest of the world that we stand where we stood, that we are not going to allow ourselves to be diverted from our path by the exigencies of the immediate situation. We shall do what is necessary to defend ourselves - defend ourselves by arms, and not only with arms but with the spiritual resources of our people.