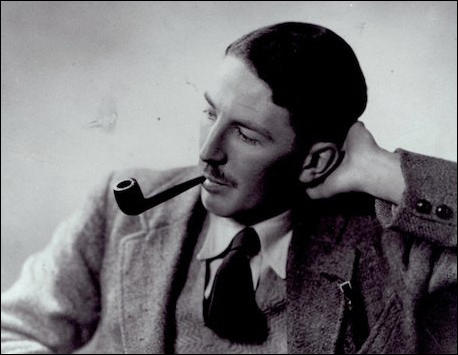

Gordon Welchman

Gordon Welchman, the youngest of three children of William Welchman and Elizabeth Marshall Welchman, was born at Fishponds, near Bristol, on 15th June 1906. His father was a missionary who became a country parson.

Welchman was educated at Marlborough College and in 1925 he won a place at Trinity College. In the mathematical tripos he obtained a first class in part one (1926) and part two (1928). He then went on to teach at Cheltenham for one year before returning to Cambridge University where he became a fellow of Sidney Sussex College in 1929. (1)

Alastair Denniston, the head of the Government Code and Cypher School (GCCS), had a problem dealing with the Enigma Machine. As Peter Calvocoressi, the author of Top Secret Ultra (2001) has pointed out: "Over the years the Germans progressively altered and complicated the machine and kept everything about it more and more secret. The basic alterations from the commercial to the secret military model were completed by 1930/31 but further operating procedures continued to be introduced." (2)

Gordon Welchman and GCCS

Denniston realised that in order to deal effectively with this problem he had begun to recruit a number of academics to help work with the Government Code and Cypher School (GCCS). This included people like Gordon Welchman and Alan Turing. One of Denniston's colleagues, Josh Cooper, told Michael Smith, the author of Station X: The Codebreakers of Bletchley Park (1998): "He (Denniston) dined at several high tables in Oxford and Cambridge and came home with promises from a number of dons to attend a territorial training course. It would be hard to exaggerate the importance of this course for the future development of GCCS. Not only had Denniston brought in scholars of the humanities of the type of many of his own permanent staff, but he had also invited mathematicians of a somewhat different type who were especially attracted by the Enigma problem." (3)

According to codebreaker, Mavis Batey, Turing went to one of the first of the training courses on codes and ciphers at Broadway Buildings. Turing was put on Denniston's "emergency list" for call up in event of war and was invited to attend meetings being held by top codebreaker, Alfred Dilwyn Knox to "hear about progress with Enigma, which immediately interested him... unusually, considering Denniston's paranoia about secrecy, it is said that Turing was even allowed" to take away important documents back to the university. (4)

The recruitment and employment of skilled academics was expensive and so, once again, Denniston had to write to the Treasury to ask for financial assistance: "For some days now we have been obliged to recruit from our emergency list men of the Professor type with the Treasury agreed to pay at the rate of £600 a year. I attach herewith a list of these gentleman already called up together with the dates of their joining." (5) R. V. Jones, one of those academics who Denniston recruited, later claimed that his actions during this period "laid the foundations of our brilliant cryptographic success". (6)

Francis Harry Hinsley, the author of British Intelligence in the Second World War (1979-1990) has pointed out: "In 1937 Denniston had begun to recruit a number of dons who were to join GCCS on the outbreak of war. His contacts with academics who had been members of Room 40 OB helped him to choose such men as Alan Turing and Gordon Welchman, who subsequently led the attack on Wehrmacht Enigma. Denniston's foresight, and his wise selection of the new staff, who for the first time included mathematicians, were the basis for many of GCCS's outstanding wartime successes, especially against Enigma... More than any other man, he helped it to maintain both the creative atmosphere which underlay its great contribution to British intelligence during the Second World War and the complete security which was no less an important precondition of its achievement." (7)

Enigma Machine

in the early months of 1939 Gordon Welchman and Alan Turing, attended short courses in cryptography organised by GCCS. Welchman was used to recruit other academics to GCCS. According to Sinclair McKay, Welchman was "a dazzlingly clever 33-year-old mathematics lecturer - a handsome fellow with an extremely neat moustache - swiftly proved to be an assiduous, enthusiastic and fantastically ambitious recruiting officer." (8) After the outbreak of the Second World War one of his recruits was Joan Clarke, who had just obtained a double first in Mathematics in Newnham College. (9)

A special unit was established at Bletchley Park. This was selected because it was more or less equidistant from Oxford University and Cambridge University and the Foreign Office believed that university staff made the best cryptographers. The house itself was a large Victorian Tudor-Gothic mansion, whose ample grounds sloped down to the railway station. Lodgings had to be found for the cryptographers in the town. Some of the key figures in the organization, including its leader, Alfred Dilwyn Knox, always slept in the office. (10)

Gordon Welchman continued to recruit people for the project: "Recruitment of young women went on even more rapidly than that of men. We needed more of them to staff the Registration Room, the Sheet-Stacking Room, and the Decoding Room. As with the men, I believe that the early recruiting was largely on a personal-acquaintance basis, but with the whole of Bletchley Park looking for qualified women, we got a great many recruits of high calibre." (11)

Gordon Welchman and Alan Turing

Gordon Welchman worked closely with Alan Turing and Hugh Alexander. According to his biographer, Robin Denniston: "Some of his key technical solutions had already been devised by the Poles and by others at Bletchley, but he instinctively grasped a whole range of problems, possibilities, and solutions which included two vital mathematical constructs as well as a concept of the total process required, from the intercepted German ciphered traffic to passing on significant intelligence implications to the commanders in the field - a highly complex logistical operation for which total secrecy was an added condition.... Early in 1940 Alan Turing had the idea of making a machine which would test all possible rotor positions of the Enigma to find those at which a given cipher text could be transformed into a plain text. Welchman greatly improved on Turing's design by his invention of a device known as a diagonal board, which Turing himself immediately recognized to be invaluable." (12)

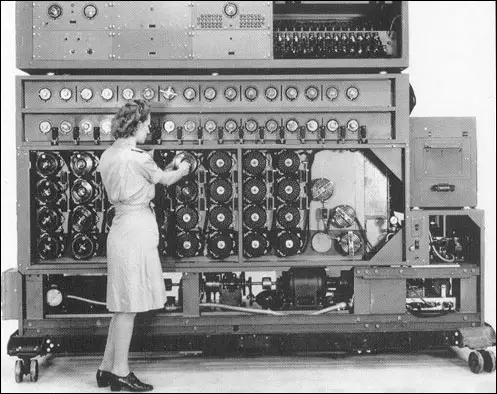

Turing finalized the design at the beginning of 1940, and the job of construction was given to the British Tabulating Machinery factory at Letchworth. The engine (called the "Bombe") was in a copper-coloured cabinet. (13) "The result was a huge machine six-and-a-half feet tall, seven feet long and two feet wide. It weighed over a ton, with thirty-six 'scramblers' each emulating an Enigma machine and 108 drums selecting the possible key settings." (14) Its chief engineer, Harold Keen, and a team of twelve men, built it in complete secrecy. Keen later recalled: "There was no other machine like it. It was unique, built especially for this purpose. Neither was it a complex tabulating machine, which was sometimes used in crypt-analysis. What it did was to match the electrical circuits of Enigma. Its secret was in the internal wiring of (Enigma's) rotors, which 'The Bomb' sought to imitate." (15)

To be of practical use, the machine would have to work through an average of half a million rotor positions in hours rather than days, which meant that the logical process would have to be applied to at least twenty positions every second. (16) The first machine, named Victory, was installed at Bletchley Park on 18th March 1940. It was some 300,000 times faster than Rejewski's machine. (17) "Its initial performance was uncertain, and its sound was strange; it made a noise like a battery of knitting needles as it worked to produce the German keys." (18) They were described by operators as being "like great big metal bookcases". (19)

Frederick Winterbotham was the chief of Air Intelligence at MI6. He later described the moment when Major General Sir Stewart Menzies, the chief of MI6, first gave him copies of German secret messages: "It was just as the bitter cold days of that frozen winter were giving way to the first days of April sunshine that the oracle of Bletchley spoke and Menzies handled me four little slips of paper, each with a short Luftwaffe message on them... From the Intelligence point of view they were of little value, except as a small bit of administrative inventory, but to the back-room boys at Bletchley Park and to Menzies... they were like the magic in the pot of gold at the end of the rainbow. The miracle had arrived." (20)

Gordon Welchman continued to play an important role in Bletchley Park: "He (Welchman) had practical gifts and a strong personality. Once it was clear that Bletchley Park would be able to read enemy traffic on a massive scale he established the need for increased facilities and close co-operation between the intercepting stations, the cryptographers, the intelligence processors, and the ultimate users. An informed view is clear that the task of converting the original breakthrough into an efficient user of the material was one for which Welchman should receive much of the credit." (21)

Commander Edward W. Travis replaced Alastair Denniston as head of GCCS in February, 1941. (22) Later that year, Gordon Welchman, Hugh Alexander, Alan Turing and Stuart Milner-Barry wrote a letter to Winston Churchill concerning the funding of GCCS: "Some weeks ago you paid us the honour of a visit, and we believe that you regard our work as important. You will have seen that, thanks largely to the energy and foresight of Commander Travis, we have been well supplied with the 'bombes' for the breaking of the German Enigma codes. We think, however, that you ought to know that this work is being held up, and in some cases is not being done at all, principally because we cannot get sufficient staff to deal with it. Our reason for writing to you direct is that for months we have done everything that we possibly can through the normal channels, and that we despair of any early improvement without your intervention."

The men added: "We have written this letter entirely on our own initiative. We do not know who or what is responsible for our difficulties, and most emphatically we do not want to be taken as criticising Commander Travis who has all along done his utmost to help us in every possible way. But if we are to do our job as well as it could and should be done it is absolutely vital that our wants, small as they are, should be promptly attended to. We have felt that we should be failing in our duty if we did not draw your attention to the facts and to the effects which they are having and must continue to have on our work, unless immediate action is taken." (23)

Churchill told his principal staff officer, General Hastings Ismay: "Make sure they have all they want on extreme priority and report to me that this has been done." (24) By the end of 1942 there were 49 Turing machines. As part of the recruitment drive, the Government Code and Cypher School placed a letter in the Daily Telegraph. They issued an anonymous challenge to its readers, asking if anybody could solve the newspaper's crossword in under 12 minutes. It was felt that crossword experts might also be good codebreakers. The 25 readers who replied were invited to the newspaper office to sit a crossword test. The six people who finished the crossword first were interviewed by military intelligence and recruited as codebreakers at Bletchley Park. (25)

After the war Gordon Welchman moved to the United States he concentrated on the development of secure communications systems for the US military. He joined the Mitre Corporation in 1962. Welchman's activities at the Government Code and Cypher School remained a secret until Frederick Winterbotham published his book, The ULTRA Secret (1974). Welchman wrote his own account The Hut Six in 1982.

Gordon Welchman died on 8th October 1985 at Newburyport, Massachusetts.

Primary Sources

(1) Gordon Welchman, The Hut Six (1982)

Recruiting for Hut 6 went fast. Travis produced a scientist, John Colman, to take charge of the Intercept Control Room, which was to maintain close contact with the intercept stations. Colman was soon joined by another scientist, George Crawford, a former schoolmate of mine at Marlborough College. Travis also persuaded London banks to send us some of their brightest young men to handle the continuous interchange of information with intercept stations. Thus, very soon, we had an intercept control team large enough to operate round the clock. They quickly established close and very friendly relations with the duty officers at Chatham.

For my part, I quite shamelessly recruited friends and former students. Stuart Milner-Barry had been in my year at Trinity College, Cambridge, studying classics while I studied mathematics. He was not enjoying being a stockbroker, and was persuaded to join me at Bletchley Park. He arrived around January 1940, when the Hut 6 organization was about thirty strong, bringing with him the largest pipes I have ever seen smoked. Stuart in turn recruited his friend, Hugh Alexander, who had been a mathematician at Kings College, Cambridge, and was then Director of Research in the John Lewis Partnership, a large group of department stores. They brought us unusual distinction in chess: Alexander was the British Chess Champion, while Milner-Barry had often played for England and was chess correspondent for the London Times.

(2) Alan Hodges, Alan Turing: the Enigma (1983)

The crucial discovery was that something like this could be done for the actual military Enigma, with its plugboard swapping taking place both before and after entry into the rotors of the basic Enigma. But the discovery was not immediate, nor was it the product of a single brain. It required a few months, and there were two figures primarily involved. For while Jeffries looked after the production of the new perforated sheets, the other two mathematical recruits, Alan and Gordon Welchman, were responsible for devising what became the British Bombe.

It was Alan who had begun the attack, Welchman having been assigned to traffic analysis, and so it was he who first formulated the principle of mechanising a search for logical consistency based on a "probable word". The Poles had mechanised a simple form of recognition, limited to the special indicator system currently employed; a machine such as Alan envisaged would be considerably more ambitious, requiring circuitry for the simulation of `implications' flowing from a plugboard hypothesis, and means for recognising not a simple matching, but the appearance of a contradiction.

(3) Gordon Welchman, The Hut Six (1982)

Recruitment of young women went on even more rapidly than that of men. We needed more of them to staff the Registration Room, the Sheet-Stacking Room, and the Decoding Room. As with the men, I believe that the early recruiting was largely on a personal-acquaintance basis, but with the whole of Bletchley Park looking for qualified women, we got a great many recruits of high calibre.

(4) Alan Turing, Gordon Welchman, Hugh Alexander, and Stuart Milner-Barry, letter to Winston Churchill (21st October, 1941)

Some weeks ago you paid us the honour of a visit, and we believe that you regard our work as important. You will have seen that, thanks largely to the energy and foresight of Commander Travis, we have been well supplied with the 'bombes' for the breaking of the German Enigma codes. We think, however, that you ought to know that this work is being held up, and in some cases is not being done at all, principally because we cannot get sufficient staff to deal with it. Our reason for writing to you direct is that for months we have done everything that we possibly can through the normal channels, and that we despair of any early improvement without your intervention...

We have written this letter entirely on our own initiative. We do not know who or what is responsible for our difficulties, and most emphatically we do not want to be taken as criticising Commander Travis who has all along done his utmost to help us in every possible way. But if we are to do our job as well as it could and should be done it is absolutely vital that our wants, small as they are, should be promptly attended to. We have felt that we should be failing in our duty if we did not draw your attention to the facts and to the effects which they are having and must continue to have on our work, unless immediate action is taken.

References

(1) Robin Denniston, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004-2014)

(2) Peter Calvocoressi, Top Secret Ultra (1980) page 31

(3) Michael Smith, Station X: The Codebreakers of Bletchley Park (1998) page 16

(4) Mavis Batey, Dilly: The Man Who Broke Enigmas (2009) page 71

(5) Alastair Denniston, memo to the Treasury (September, 1937)

(6) R. V. Jones, Most Secret War: British Scientific Intelligence 1939-1945 (1978) page 98

(7) Francis Harry Hinsley, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004-2014)

(8) Sinclair McKay, The Secret Life of Bletchley Park (2010) pages 16 and 18

(9) Lynsey Ann Lord, Joan Clarke Murray (2008)

(10) Penelope Fitzgerald, The Knox Brothers (2002) page 228-229

(11) Gordon Welchman, The Hut Six (1982)

(12) Robin Denniston, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004-2014)

(13) Sinclair McKay, The Secret Life of Bletchley Park (2010) page 95

(14) Nigel Cawthorne, The Enigma Man (2014) page 55

(15) Harold Keen, interviewed by Anthony Cave Brown (c. 1970)

(16) Anthony Cave Brown, Bodyguard of Lies (1976) page 23

(17) Nigel Cawthorne, The Enigma Man (2014) page 58

(18) Alan Hodges, Alan Turing: the Enigma (1983) page 231

(19) Mary Stewart, interviewed in the documentary The Men Who Cracked Enigma (2003)

(20) Frederick Winterbotham, The ULTRA Secret (1974) page 15

(21) Robin Denniston, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004-2014)

(22) Francis Harry Hinsley, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004-2014)

(23) Hugh Alexander, Alan Turing, Gordon Welchman and Stuart Milner-Barry, letter to Winston Churchill (21st October, 1941)

(24) Alan Hodges, Alan Turing: the Enigma (1983) page 279

(25) Simon Singh, The Code Book: The Secret History of Codes & Code-Breaking (2000) page 181