George Cram Cook

George Cram Cook, the son of a lawyer, was born in Davenport, Iowa on 7th October 1875. An intelligent student, "Jig" Cook completed his bachelor's degree at Harvard University in 1893. He continued his studies at the University of Heidelberg and at the University of Geneva.

On his return to the United States he taught English literature at the University of Iowa from 1895 until 1899. He also taught at Stanford University before taking up writing full-time. For a time he worked under Floyd Dell on the Chicago Evening Post Literary Review. Dell later recalled that Cook was "a romantic-philosophical novelist of whose reactionary Nietzschean-aristocratic conceptions of an ideal society founded upon a pseudo-Greek slavery, I as a socialist had totally disapproved." Dell later commented in his autobiography, Homecoming (1933) that later he came under the influence of the writing of Peter Kropotkin and considered himself an anarchist: "This immediate and deep friendship took me out to George's farm at every opportunity. In our discussions he was converted from his Nietzschean aristocratic anarchist philosophy to Socialism."

Jig Cook wrote during this period: "I do not aspire to be, in the great sense of the word, a scholar. I hope to prove some day, writing and teaching, a person of tastes and talent, able to help people understand and love rightly the things which are beautiful." As Linda Ben-Zvi pointed out: "Throughout his life Jig Cook attempted to be the conduit through which others realized their inner potential."

In May 1902 Cook married Sara Herndon Swain. After moving to Buffalo he completed his first book, Roderick Taliaferro, that was published in 1903. The marriage was not a success and in 1906 he began an affair with Mollie Price. Cook wrote in his diary that "love is moral even without marriage but marriage is immoral without love." Mollie was an anarchist who believed in free-love and was not concerned that Cook was a married man.

Susan Glaspellmet Cook in November 1907. Glaspell describes the meeting in her biograpahy of Cook, The Road to the Temple (1926): "It was in Chicago he (George Cook) was married, to a girl of beauty and charm whom he met through friends there, and after a summer at the Cabin they went to California, where Jig will teach English at Leland Standford University under Professor Anderson, his old teacher. Already he has the idea, which grows important in his life, that it is better a writer make his living in some other way than by writing. It seemed to him that this either conscious or unconscious adapting of one's work to what it will mean in money was as a blight. He thought there were ways of freeing oneself; he cared enough about it to shape his life toward that ideal of giving the mind free play."

Floyd Dell was with Cook when he met Susan Glaspell for the first time. "George and I called upon Susan Glaspell, a young newspaperwoman who began a brilliant career as a novelist. She read us some of her just-finished novel, The Glory of the Conquered, the liveliness and humour of which we admired greatly, though George deplored to me on the way home the lamentable conventionality of the author's views of life. Susan was a slight, gentle, sweet, whimsically humourous girl, a little ethereal in appearance, but evidently a person of great energy, and brimful of talent; but, we agreed, too medieval-romantic in her views of life."

In January 1908 Cook was granted a divorce from Sara. Three months later he married Mollie Price. However, the relationship was soon in trouble. Floyd Dell commented that the problem was that "marriage had tamed this wild bird." The situation was complicated by the birth of their children, Nilla and Harl.

Cook eventually left his wife and children to live with Susan Glaspell. The couple moved to Provincetown, a small seaport in Massachusetts, where they married on 14th April, 1913. They joined a group of left-wing writers including Floyd Dell, John Reed, Mary Heaton Vorse, Mabel Dodge, William Zorach, Harry Kemp, Neith Boyce, Theodore Dreiser, Hutchins Hapgood and Louise Bryant.

As Barbara Gelb, the author of So Short a Time (1973), has pointed out: "Cook and Susan Glaspell had participated, along with Reed, in the birth of the Washington Square Players in Greenwich Village and had written a one-act play to help launch a summer theater in Provincetown in 1915. Cook dreamed of creating a theater that would express fresh, new American talent, and after his modest beginning in the summer of 1915, began urging his friends to provide scripts for an expanded program for the summer of 1916. None of his friends were professional playwrights, but several, like Reed, were journalists and short-story writers. Their unfamiliarity with the dramatic form was, in Cook's opinion, precisely what suited them to be pioneers in his new theater and to break up some of the old theater molds; Cook wanted them to disregard the rules and precepts of the commercial Broadway theater, and to stumble and blunder and grope their way toward a native dramatic art."

In 1915 several members of the group established the Provincetown Theatre Group. A shack at the end of the fisherman's wharf was turned into a theatre. Later, other writers such as Eugene O'Neill and Edna St. Vincent Millay joined the group. The play, Suppressed Desires, that he co-wrote with his wife Susan Glaspell, was one of the first plays performed by the group. He also wrote the anti-war play, The Athenian Women during the First World War.

Many of the productions that appeared at Provincetown were later transferred to New York City. This were initially performed at an experimental theatre on MacDougal Street but some of the plays, especially by Susan Glaspell and Eugene O'Neill were critical successes on Broadway. The Provincetown Theatre Group came to an when its star writer, Eugene O'Neill, decided to deal directly with Broadway.

As Floyd Dell pointed out: "George Cook had come to a crisis in his life; he was spiritually centered in the plays of Eugene O'Neill, and now the young playwright had decided to deal directly with Broadway, refusing to allow the Provincetown Players to put on his plays before they went uptown. This was an entirely reasonable decisions on his part, but it broke George Cook's heart."

According to Susan Glaspell he remained a socialist but was disillussioned by the Russian Revolution. He told his friends: "Unless the Socialist movement is going to make room in itself for a culture as broad and imaginative as any aristocratic culture, it would be better for the world that it perish from the earth."

Cook eventually came to the conclusion that the Provincetown Theatre Group had failed: "Three years ago, writing for the Provincetown Players, anticipating the forlornness of our hope to bring to birth in our commercial-minded country a theatre whose motive was spiritual... I am now forced to confess that our attempt to build up, by our own life and death, in this alien sea, a coral island of our own, has failed. The failure seems to be more our own than America's. Lacking the instinct of the coral-builders, in which we could have found the happiness of continuing ourselves toward perfection, we have developed little willingness to die for the thing we are building. Our individual gifts and talents have sought their private perfection."

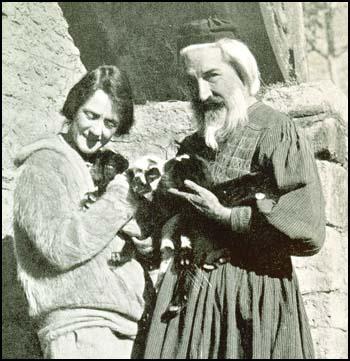

The two main figures in the group, Cook and Susan Glaspell, suspended operations and moved to Greece. According to Barbara Gelb, at this time: "Cook had a mane of white hair and a habit of twisting a shaggy lock between his fingers when moved or excited." Glaspell had to visit the United States but when she returned she found him unwell: "Jig was not well. I found him thinner when I returned from America, and he was thinner now than then. He would get tired of the food.... His thinner face, and his beard, made him look older. His moustache was black, like the eyebrows, but the beard, like his hair, was white... He looked like a man of the mountain; more and more his eyes were the eyes of a seer."

Cook was diagnosed as suffering from typhus or glanders. However, he was too weak to be taken to Athens. The doctor told Susan Glaspell that he was dying: "Most of the time was unconscious, but I could call him to a moment's consciousness. His eyes and mine could meet, and know. I came to feel I must not do it, that it might call him into what I must shield him from knowing... It was at midnight of the second day that Jig, who had been in much distress, fell back on his pillows. His breathing slowed. There came that moment when he did not breathe again."

George Cram Cook died on 14th January, 1924. In his obituary, The Nation wrote: "George Cram Cook... was a brave enthusiast, whose experimental eagerness helped break new paths for the American theatre and drama. He was a playwright and novelist but, beyond these things, he was extraordinarily a person, exerting an incalculable personal force and influence. That influence is itself not easy to describe, except as a civilizing influence, or perhaps a Utopian influence; he made people ashamed of surrender to an ignoble world, he made them try to do the beautiful and impossible things of which they dreamed - and that attempt, which is often enough ridiculous, is the best the world has yet been able to offer in the way of civilization anywhere."

Floyd Dell wrote: "I loved him, and I would have had his life and death other than they were. I would have him die for Russia and the future, rather than Greece and the past." Greek Coins: Poems of George Cram Cook was published posthumously in 1925.

Primary Sources

(1) Susan Glaspell, The Road to the Temple (1926)

It was in Chicago he (George Cook) was married, to a girl of beauty and charm whom he met through friends there, and after a summer at the Cabin they went to California, where jig will teach English at Leland Standford University under Professor Anderson, his old teacher. Already he has the idea, which grows important in his life, that it is better a writer make his living in some other way than by writing. It seemed to him that this either conscious or unconscious adapting of one's work to what it will mean in money was as a blight. He thought there were ways of freeing oneself ; he cared enough about it to shape his life toward that ideal of giving the mind free play.

(2) Linda Ben-Zvi, Susan Glaspell: Her Life and Times (2005)

Throughout his life Jig Cook attempted to be the conduit through which others realized their inner potential.... This he tried to do for Susan, the Provincetown Players, and Eugene O'Neill: to inspire them to be the best they could be. Their successes would validate his beliefs. Such a goal may seem the mark of an egocentric who wished to bend others to his will. In practice Jig seems to have been the true idealist, desiring to fire others with his passion rather than aggrandize himself in the process. Susan understood this need in her husband and respected it. By the time she fell in love with Jig, she was already over thirty, a strong, successful woman. This did not change. Her individuality was not altered by their marriage, rather her life was enhanced by their love. There is a difference. Jig was not an easy man to live with; his passions were numerous and scattered, his attention span short, his frustrations over his failures great. But Susan, confident and steady in her own life, was able to provide ballast for her husband. It was she who supported the family through her writing; he took little money from his wealthy family and brought in little himself. It was also she who dealt with many of the more mundane elements of their joint project: the Provincetown Players. He inspired the group; she soothed it and helped it run more efficiently. There seemed to be little competition between them. Those who knew them mentioned their rare compatibility.

A man of great passion, Jig Cook thrust himself into each idea and relationship with his whole being, but never for long. His interests were too diverse, his "enthusiasms" to use his word - too short-lived. He was a great talker and a catalyst for great talk, whether at his cabin in Davenport in 1907, with the young Floyd Dell and Susan, discussing the ideas of Ernst Haeckel and the possibilities of free love; around a table at Schlogl's in Chicago over drinks, trading stories and ideas with newspaper people; or at the Liberal Club, with his Greenwich Village friends and members of the Provincetown Players, planning for a new theatre in America. He was also a great doer and encouraged others to take on similar projects.

(3) Floyd Dell, Homecoming (1933)

A society of freethinkers was to be formed in Davenport. I was invited to the first meeting, and there I saw George Cook, the novelist. Our common enthusiasm for Haeckel's philosophy enabled us to become friends.

This immediate and deep friendship took me out to George's farm at every opportunity. In our discussions he was converted from his Nietzschean - aristocratic - anarchist philosophy to Socialism.

Truck-farming was a part of George's theory of the artistic life; the idea was the writer should not be economically dependent upon his writing, but should remain free to write what he chose.

(4) In his autobiography Homecoming, Floyd Dell wrote about how George Gig Cook met Susan Glaspell in 1903.

George and I called upon Susan Glaspell, a young newspaperwoman who began a brilliant career as a novelist. She read us some of her just-finished novel, The Glory of the Conquered, the liveliness and humour of which we admired greatly, though George deplored to me on the way home the lamentable conventionality of the author's views of life. Susan was a slight, gentle, sweet, whimsically humourous girl, a little ethereal in appearance, but evidently a person of great energy, and brimful of talent; but, we agreed, too medieval-romantic in her views of life.

(5) Floyd Dell, Homecoming (1933)

My old friend George - everybody called him "Jig" Cook now seethed with ideas and ambitions; he corresponded with university men about the organization of a college teacher's union, which to some people then seemed absurd, but which later came into existence. But he could not seem to write stories which would sell to the magazines. This was partly because the magazines wanted, in the main, something rather ignoble; but it was also because his stories, so magnificent when he talked about them, were not magnificent when he wrote them. He was discouraged. But among his Provincetown friends, Mary Vorse, Wilbur Steele, John Reed, Hutchins Hapgood, he saw fine talents which had managed to make some kind of honorable and successful terms with the existing literary market; and that was what he was trying to do.

Shortly after I came, he told me he had begun a novel about me. I reflected that if there was a novel in me, I really ought to do it myself. I thought about it, and named the youth who had been myself "Felix Fay"; and then a title occurred to me - Moon-Calf. And I set to work and outlined the first chapters. When I sketched out some very painful memory, it was a great relief; but it was slow work...

But what really happened, I think, was that when I was a boy-poet and George a married man trying to keep his marriage from going to smash, I - as his Lost Youth - made him uncomfortable. One's Lost Youth in another person is always an anarchic and socially liberating (or disintegrating) influence. Now the odd thing is that George was also my Lost Youth. And when we both needed that influence, we became tremendously friends, and got, besides, what else there was to get from that friendship - George taking my Socialism, and I his rich, deep, human knowledge of the world. But now both of us craved stability, we didn't wish any disturbing, anarchic, liberating influences, we profoundly hoped to settle down - and we were rather afraid of each other. We didn't know why; but we were too much alike in our romantic weaknesses of character - and in the other as in a mirror each could see too clearly a picture of himself that he didn't quite like to look at. We didn't want to spend the rest of our lives getting ourselves mated and unmated and mated again; we wanted to stay mated and use our literary talents in some way that would be of some use in the world. George needed terribly some literary success, for he felt that he had to justify the break-up of his marriage.

Mollie had taken the children to California, where she was going to teach school and support them; meanwhile "Mamie" Cook was helping her with money. George sat and thought about his children a

good deal, twisting his forelock; he had a bad conscience. He was happy in his love, happy as he had never been before; but the cost of getting it had been a terrible one that he would never cease to feel.

(6) Susan Glaspell, The Road to the Temple (1926)

Few Americans, I think, felt the war from so profound a tragic sense. "Feeling about life (its immensity, its vast antiquity, its minute complexity) and love, which is the farthest point from death that living things attain in their vibration between life and death."

He spoke often of what Nietzsche had said: "All nations claim to be armed for self-defence. Then let Germany, the strongest, disarm." He coveted for his own country that gesture Germany had not made.

Later, in notes for a play, he writes: " Statesman with vision of the surprising safety of disarmament. Grandeur of it. Profound courage of it. The strength of Christ."

He was thrilled by "Too proud to fight," and saw a great drama in The Rise and Fall of President Wilson.

Only once did he feel like going into the war himself, when Germany went on into Russia after Russia had stopped. In war politics he felt as true many things which have since been disclosed. His ardour through those years went to Russia. When the draft included the men of his age he wanted to state his refusal. I urged delay, stressing his own idea of keeping burning, to the measure we could, the light of creative imagination. My fears were for where his intensity might take him, once that fight were begun. But he wrote on the questionnaire he returned : "I will not go into Russia to fight or police Russian working-men."

He had remained a Socialist, but political interests had become less personal, absorbed in the creation of his own community. " Aridity, a dryness, about generalizations such as the great generalization of Socialism, unless these are given body by fresh and ever fresh facts. A generalization is like an organism. In order to remain living it must be fed with particulars, must eliminate waste.

"Unless the Socialist movement is going to make room in itself for a culture as broad and imaginative as any aristocratic culture, it would be better for the world that it perish from the earth."

(7) Linda Ben-Zvi, Susan Glaspell: Her Life and Times (2005)

What the real Mollie Price was like is hard to say, since her part of the correspondence is lost (just as Susan's letters to Jig do not survive). Mollie seems to have been an independent, vivacious twenty woman, who loved jig but was not willing to give up her own life or lifestyle while waiting for him to win his divorce. An anarchist, espousing free love, she practiced what she preached, having sex with him at their first meeting, even before she knew his name. The setting was near Blackhawk's Watch Tower, on the Moline side of the Mississippi, a spot that Susan and Jig would also seek out when they wanted to be alone. For the lonely Jig, who had taken time out from his summer farming to attend the Press Club meeting, she seemed like a miracle sent to save him. "I'm good for nothing-nothing but one thing," he writes her a few days after they met. There is no salutation or signature on the letter, but on the reverse side he has drawn the signs for male and female and added the words, "There is destiny that shapes our end." Two days later he writes, "It cannot be possible that I went with a girl at sunset down the woods to the river bank. She didn't sit on a rock unbound and speak my language ... her arms opened and locked me in.... I never wanted anything so much in my life. I did not think a man could get so excited." He is suddenly alive with plans for the future: He will meet her in Chicago, although he knows that he shouldn't, since this is his busy period on the farm. Yet, he can't be reasonable now: "I love you gently, tenderly, reverently. At this moment passion sublimates itself to pure spirit. My body thinks one thought - you.... I am not merely happy. I am in bliss." Even in love, Jig is Jig. He cannot resist making lists. Lest she forget, he enumerates the number of times she "felt the fluid jet." He also assigns names. His penis is William, her vagina is Peggy - coincidentally the name of his favorite dog - allowing him punning latitude. Ever exact, he also offers the specific size of his member: "six and a half inches in circumference." Passion does not deflect habit (but it may exaggerate it).

(8) Barbara Gelb, So Short a Time (1973)

Widowed in 1915 for the second time, Mary Heaton Vorse supported herself and her children by free-lance writing. She first visited Provincetown during the summer of 1906 to give her children sea air, fell in love with the village, and bought an old house that she later turned into a year-round residence. Hutchins Hapgood, the journalist, a college friend of Mary Vorse's first husband, was the second of the writers to arrive, and after him came other New Yorkers in search of a summer refuge. Two among them were George Cram Cook and his wife, Susan Glaspell.

Cook, called "Jig" by his friends, was a forty-three-year-old Greek scholar and university professor from Davenport, Iowa. He had left a wife and children to marry Susan Glaspell, a burgeoning writer. Cook had a mane of white hair and a habit of twisting a shaggy lock between his fingers when moved or excited.

Susan Glaspell, a delicate, sad-eyed, witty woman, worshiped her husband and devoted herself equally to him and to her writing; it was she who provided the backbone of their income.

Cook and Susan Glaspell had participated, along with Reed, in the birth of the Washington Square Players in Greenwich Village and had written a one-act play to help launch a summer theater in Provincetown in 1915. Cook dreamed of creating a theater that would express fresh, new American talent, and after his modest beginning in the summer of 1915, began urging his friends to provide scripts for an expanded program for the summer of 1916. None of his friends were professional playwrights, but several, like Reed, were journalists and short-story writers. Their unfamiliarity with the dramatic form was, in Cook's opinion, precisely what suited them to be pioneers in his new theater and to break up some of the old theater molds; Cook wanted them to disregard the rules and precepts of the commercial Broadway theater, and to stumble and blunder and grope their way toward a native dramatic art. The idea appealed to Reed and to other of Cook's friends such as Mary Vorse and Hutchins Hapgood, and a number of them, including Reed and Louise, agreed to write one-act plays for production that summer.

Reed, like Cook, believed that a native American theater could be prodded into being. He was full of enthusiasm for a performance he had seen in a Mexican village that expressed the traditional folk spirit in terms of the contemporary lifestyle of the villagers.

The Cooks and several of their friends commandeered an old fishhouse at the end of a tumbledown wharf owned by Mary Vorse, and christened it the Wharf Theater. Little more than a shell, the building was twenty-five feet square and fifteen feet high. Through the planks of its floor at high tide the bay could be seen and heard and smelled. Under Cook's direction, an ingenious stage was built. Only ten by twelve feet, it was sectional and mobile and could be slid backward onto the end of the wharf through two wide doors at the rear of the theater, to provide an effect of distance.

When Reed and Louise arrived in Provincetown, they found their friends engrossed by the theater project. The company already numbered thirty, each member having contributed five dollars toward the cost of mounting the summer program. Cook wanted to stage Reed's one-act play, Freedom, for the opening bill and Louise, urged by Cook, began writing her own one-act play to be staged later in the summer. Both Reed and Louise were swept up in the excitement of the first production. Along with Freedom, a satire about four prisoners with divergent ideas on what it means to be free, the opening bill included Trifles, by Neith Boyce, the novelist, and a joint effort by Cook and his wife called Suppressed Desires, a spoof of the new vogue for psychoanalysis. At fifty cents a ticket, this first bill sold out for its entire run, and Cook, encouraged by the response, sent out a letter asking for a one dollar subscription for the remaining three bills of the season-hoping that nine more - one-act plays would materialize.

(9) Floyd Dell, Homecoming (1933)

George Cook brought the Provincetown Players to New York in 1916, and a theatre was made out of a stable on Macdougal Street. There was a play of mine, King Arthur's Socks, on the first bill, and three others later. I sympathized deeply with George's hopes, though for the life of me I could not share his profound admiration for Eugene O'Neill, whose plays seemed to me obviously destined for popular success, but whose romantic point of view did not interest me. As for a chance to work in a little theatre, that was an old story to me; I had had my own little theatre in the Liberal Club for two years - I had been playwright, stage designer, scene painter, stage manager and actor; it had been great fun, but I could not make a religion of it, as George seemed bent upon doing. But I was sufficiently an idealist about the little theatre to be shocked by the ruthless egotisms which ran rampant in the Provincetown Players. I saw new talent rebuffed - though less by George than by the others - its fingers brutally stepped on by the members of the original group, who were anxious to do the acting whether they could or not - and usually they could not; but I need not have wasted my sympathy, for the new talent, more robust than I supposed, clawed its way up on to the raft, and stepped on other new fingers, kicked other new faces as fast as they appeared. It was all that one had ever heard about Broadway, in miniature; but nobody seemed to mind. There was devotion and unselfishness, a great deal of it, in the group, from first to last; but these qualities were only what I expected. And what did astonish and alienate me was the meanness, cruelty and selfishness which this little theatrical enterprise brought out in people, many of them my old friends, whom I had known only as generous and kind.

The internal wars of The Masses were conventions of brotherly love compared to the eternal poisonous rowing of the Provincetown Players. But over this crew of artistic ruffians, seething with jealousy, hatred and self-glorification, George ruled, with the aid of a punch-bowl, like one of the Titans. He really believed in the confounded thing! And his vision it was that held this Walpurgis-night mob together in some kind of Homeric peace and amity. Drunk and sober, he whipped and hell-raised and praised and prayed it into something that - though this was not what he was aiming at - did impress Broadway. Many fine talents got their chance in that maelstrom. George prided himself upon his efficiency, and, so far as I could see, hadn't any. It was my impression (which may have been inaccurate) that he could not delegate authority; he thought that nothing could get done without his doing it himself, and he ran hastily from one thing to another, and nobody was allowed to drive a nail if George were there to do it - only, under the circumstances, he couldn't be everywhere, and things did get done after a fashion by others, subject to his mournful disapproval. He fell madly in love with one toy after another - when a wind-machine was acquired, hardly a word of dialogue could be heard for months, all being drowned out by the wind-machine; arid the "dome" became a nuisance, it was so over-used; when I was too busy to stage-manage a play of mine, he turned it over to some new enthusiast with lunatic ideas, who put the actors on stilts, so that nothing could be heard except clump, thump, bump! Nothing was too mad or silly to do in the Provincetown Theatre, and I suffered some of the most excruciating hours of painful and exasperated boredom there as a member of the audience that I have ever experienced in my life. George tolerated everybody and believed in everybody and egregiously exploited everybody; and everybody loved him. He was the only one, it would seem, who could have presided over this chaos and kept it from spontaneous combustion. His own play, The Athenian Women, was noble in idea and conception, but somehow not dramatic, though I tried to persuade myself that it was at the time. Another play of his, The Spring, had a moving idea in it, muffled in an awkward plot; George's father had died and left him some money, and George took and blew in a great hunk of it, putting his play on Broadway, where it hadn't a chance; I thought that plain egotism, and vulgar anxiety for "fame", and rank selfishness, in not considering the needs of his children - all of which may have been unjust, but which is what I, his old adorer, thought of him. And then his mother, "Mamie" Cook, came to New York to be with her big boy, and sewed costumes for the Provincetown Players, and mothered the theatre. To me, the justification of the Provincetown Players' existence - aside from discovering Eugene O'Neill, a mixed blessing - and he would have been discovered anyway, I thought - was in two plays: one was Susan Glaspell's The Inheritors; a beautiful, true, brave play of war-time. In this play, moreover, Susan Glaspell brought to triumphant fruition something that was George Cook's, in a way that he never could - something earthy, sweet and beautiful that had not been in her own work before. To much that was praised in her plays I was not responsive - Bernice was not for me. But to my mind The Inheritors was a high moment in American drama. And I like to remember beautiful Ann Harding, first seen as the heroine of that play. The other play in which the Provincetown Theatre fully justified its existence was Edna St. Vincent Millay's profoundly beautiful Aria da Capo, a war-play too, in its own symbolic fashion, and full of the indignation and pity which war's useless slaughter had aroused in her poet's mind and heart.

I did not like George Cook during this period; he was a Great Man, in dishabille; and Great Men, whether on pedestals or in dishabille, tended to provoke only irreverence from me. But then, I did not like Eugene V. Debs to talk to; he orated blandly in private conversations, taking no particular note of whether he was talking to Tom, Dick, or Harry. I did not like Mother Jones, either; when she came into The Masses office, I retreated behind a desk and looked longingly at the fire-escape. I am sure I should not have liked Tolstoi, Goethe, Dr. Johnson, or Paul Bunyan. And how could I like Jig Cook when he was being Tolstoi, Goethe, Eugene V. Debs, Dr. Johnson, Mother Jones and Paul Bunyan all rolled into one? Once, when I felt impelled to offer him some useless personal advice upon the conduct of life, I apologetically remarked that once we had been great friends; - "Shake on that," he said, and warmly grasped my hand, and listened in troubled silence; but his life was, it seemed from the outside, hardly within his own control; it was as if he were being driven on by a daemon to some unknown goal.

For Susan Glaspell my respect and admiration grew immensely; it is a difficult position to be the wife of a man who is driven by a daemon, a position from which any mortal woman might, however great her love, shrink in dismay or turn away in weariness; but it was a position which she maintained with a sense and radiant dignity.

(10) Susan Glaspell, The Road to the Temple (1926)

People sometimes said, "Jig is not a business man," when it seemed opportunities were passed by. But those opportunities were not things wanted from deep. He had a unique power to see just how the thing he wanted done could be done. He could finance for the spirit, and seldom confused, or betrayed, by extending the financing beyond the span he saw ahead, not weighing his adventure down with schemes that would become things in themselves.

He wrote a letter to the people who had seen the plays, asking if they cared to become associate members of the Provincetown Players. The purpose was to give American playwrights of sincere purpose a chance to work out their ideas in freedom, to give all who worked with the plays their opportunity as artists. Were they interested in this ? One dollar for the three remaining bills.

The response paid for seats and stage, and for sets. A production need not cost a lot of money, Jig would say. The most expensive set at the Wharf Theatre cost thirteen dollars. There were sets at the Provincetown Playhouse which cost little more. He liked to remember " The Knight of the Burning Pestle " they gave at Leland Standford, where a book could indicate one house and a bottle another. Sometimes the audience liked to make its own set.

"Now Susan," he said to me, briskly, "I have announced a play of yours for the next bill."

"But I have no play!"

"Then you will have to sit down tomorrow and begin one." "I protested. I did not know how to write a play. I had never "studied it."

Nonsense," said Jig. "You've got a stage, haven't you?"

So I went out on the wharf, sat alone on one of our wooden benches without a back, and looked a long time at that bare little stage. After a time the stage became a kitchen, - a kitchen there all by itself. I saw just where the stove was, the table, and the steps going upstairs. Then the door at the back opened, and people all bundled up came in - two or three men, I wasn't sure which, but sure enough about the two women, who hung back, reluctant to enter that kitchen. When I was a newspaper reporter out in Iowa, I was sent down-state to do a murder trial, and I never forgot going into the kitchen of a woman locked up in town. I had meant to do it as a short story, but the stage took it for its own, so I hurried in from the wharf to write down what I had seen. Whenever I got stuck, I would run across the street to the old wharf, sit in that leaning little theatre under which the sea sounded, until the play was ready to continue. Sometimes things written in my room would not form on the stage, and I must go home and cross them out. " What playwrights need is a stage," said Jig, "their own stage."

(11) George Cram Cook, Provincetown Theatre Group (1916)

Three years ago, writing for the Provincetown Players, anticipating the forlornness of our hope to bring to birth in our commercial-minded country a theatre whose motive was spiritual, I made this promise: "We promise to let this theatre die rather than let it become another voice of mediocrity."

I am now forced to confess that our attempt to build up, by our own life and death, in this alien sea, a coral island of our own, has failed. The failure seems to be more our own than America's. Lacking the instinct of the coral-builders, in which we could have found the happiness of continuing ourselves toward perfection, we have developed little willingness to die for the thing we are building.

Our individual gifts and talents have sought their private perfection. We have not, as we hoped, created the beloved community of life-givers. Our richest, like our poorest, have desired most not to give life, but to have it given to them. We have valued creative energy less than its rewards-our sin against our Holy Ghost.

As a group we are not more but less than the great chaotic, unhappy community in whose dry heart I have vainly tried to create an oasis of living beauty.

"Since we have failed spiritually in the elemental things - failed to pull together - failed to do what any good football or baseball team or crew do as a matter of course with no word said - and since the result of this is mediocrity, we keep our promise: We give this theatre we love good death; the Provincetown Players end their story here.

Some happier gateway must let in the spirit which seems to be seeking to create a soul under the ribs of death in the American theatre.

(12) Floyd Dell, Homecoming (1933)

In Provincetown in 1915 he (George Cook) found an unknown young playwright, Eugene O'Neill, whose little one-act plays were superb and beautiful romanticizations and glorifications and justifications of failure. And now George's life had what it needed; his life was henceforth lived under the aegis of Eugene O'Neill's plays, which is dreamed of bringing to the Village and producing there.

George Cook had come to a crisis in his life; he was spiritually centered in the plays of Eugene O'Neill, and now the young playwright had decided to deal directly with Broadway, refusing to allow the Provincetown Players to put on his plays before they went uptown. This was an entirely reasonable decisions on his part, but it broke George Cook's heart. In February, the Provincetown Theatre suspended operations, and a month later, George Cook and Susan Glaspell sailed for Greece.

(13) Mabel Dodge, Intimate Memories (1933)

I wanted to get outside Provincetown where John Reed lived with Louise Bryant a little way up the street in a white clapboarded cottage that had a geranium in the upstairs bedroom window. When I saw Reed on the street, he steeled himself against me. Though I wanted to be friends, he wouldn't. People said Louise was having an affair with young Eugene O'Neill, who lived in a shack across the street with Terry Carlin and I thought Reed would be glad to see me if things were like that between him and Louise - but he wasn't. Jig Cook was writing a play - or was it Susan's play? Anyway, Louise was going to be in it. Hutch (Hutchins Hapgood) came in one evening with Jig - who was large and kind and had a shiny face with unidentified brown eyes. They were both rather drunk and they were talking theater. Jig was saying sententiously:

"Louise has very kindly consented to appear nude in that scene where she has to be carried in..."

All these people disheartened me. I didn't want to be a part of it. I preferred to stay in my own slump rather than to emerge with them. I wanted God to lift me up. If he wouldn't, then I would stay in my depths until he did.

Eugene was often drunk. Everyone drank a good deal, but it was of a very superior kind of excess that stimulated the kindliness of hearts and brought out all the pleasure of these people. Eugene's unhappy young face had desperate dark eyes staring out of it and drink must have eased him. Terry of course was always drunk. A handsome skeleton, I thought. Jig Cook was often tippling along with genial Hutch. The women worked quite regularly, even when they, too, drank; and I envied them their ease and ran away from it.

(14) Floyd Dell wrote about Susan Glaspell and George Gig Cook in 1961.

My friend George Cook died in Greece... I had heard that he got with the shepherds, and was adored by them. Susan Glaspell has told the story of those days with great sympathy in The Road to the Temple. Susan Glaspell has said in her book that she has sometimes thought I would write a book about George. He was too close to me to be just to him. I loved him, and I would have had his life and death other than they were. I would have him die for Russia and the future, rather than Greece and the past. And if I wrote a book about George, that is what I should wish him to do.

(15) The Nation (23rd January, 1924)

George Cram Cook... was a brave enthusiast, whose experimental eagerness helped break new paths for the American theatre and drama. He was a playwright and novelist but, beyond these things, he was extraordinarily a person, exerting an incalculable personal force and influence. That influence is itself not easy to describe, except as a civilizing influence, or perhaps a Utopian influence; he made people ashamed of surrender to an ignoble world, he made them try to do the beautiful and impossible things of which they dreamed - and that attempt, which is often enough ridiculous, is the best the world has yet been able to offer in the way of civilization anywhere. It was the Greeks of the Periclean age who went at it most eagerly and naively, perhaps; and in spirit George Cram Cook was a Greek of the Periclean age, strayed somehow out of his place and time into our more timid age; and after bruising himself by working a lifetime against realities which he was too eager to reshape, he strayed back again to what must have seemed his own country. He will be buried, as he wished, at Delphi.