Women's Suffrage

The struggle for women's suffrage in America began in the 1820s with the writings of Fanny Wright. In her book, Course of Popular Lectures (1829) and in the Free Enquirer, Wright not only advocated women being given the vote but the abolition of slavery, free secular education, birth control and more liberal divorce laws.

Wright received little support for her views and the next significant development did not take place until 1840 when two members of the Society of Friends, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott, travelled to London as delegates to the World Anti-Slavery Convention. Both women were furious when they, like the British women at the convention, were refused permission to speak at the meeting. Stanton later recalled: "We resolved to hold a convention as soon as we returned home, and form a society to advocate the rights of women."

Margaret Fuller was another supporter of women's rights. In her book, Women in the Nineteenth Century (1845) she wrote: "We would have every arbitrary barrier thrown down. We would have every path laid open to Woman as freely as to Man. Were this done, and a slight temporary fermentation allowed to subside, we should see crystallizations more pure and of more various beauty. We believe the divine energy would pervade nature to a degree unknown in the history of former ages, and that no discordant collision, but a ravishing harmony of the spheres, would ensue."

Samuel May, a Unitarian clergyman in Massachusetts, was one of the few men who advocated equal rights for women: "But some would eagerly ask, should women be allowed to take part in the constructing and administering of our civil institutions? Allowed, do you say? The very form of the question is an assumption of the right to do them the wrong that has been done them. Allowed! Why, pray tell me, is it from us their rights have been received? Have we the authority to accord to them just such prerogatives as we see fit and withhold the rest? No! woman is not the creature, the dependent of man but of God. We may with no more propriety assume to govern women than they might assume to govern us. And never will the nations of the earth be well-governed until both sexes, as well as all parties, are fairly represented and have an influence, a voice, and, if they wish, a hand in the enactment and administration of the laws."

However, it was not until 1848 that Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott organised the Women's Rights Convention at Seneca Falls. Stanton's resolution that it was "the duty of the women of this country to secure to themselves the sacred right to the elective franchise" was passed, and this became the focus of the group's campaign over the next few years. The only man who attended the meeting was Frederick Douglass. According to Ida Wells: "Frederick Douglass, the ex-slave, was the only man who came to their convention and stood up with them. He said he could not do otherwise; that we were among the friends who fought his battles when he first came among us appealing for our interest in the antislavery cause."

In 1866 Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Lucretia Mott, Susan B. Anthony and Lucy Stone helped establish the American Equal Rights Association. The following year, the organisation became active in Kansas where Negro suffrage and woman suffrage were to be decided by popular vote. However, both ideas were rejected at the polls.

In 1869 Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony formed a new organisation, the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA). The organisation condemned the Fourteenth and Fifteenth amendments as blatant injustices to women. The NWSA also advocated easier divorce and an end to discrimination in employment and pay.

Another group, the American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA) was formed in the same year in Boston. Leading members of the AWSA included Lucy Stone and Julia Ward Howe. Less militant that the National Woman Suffrage Association, the AWSA was only concerned with obtaining the vote and did not campaign on other issues. The campaign for women's suffrage had its first success in 1869 when the territory of Wyoming gave women the vote. However, an amendment to the federal Constitution concerning woman suffrage that was introduced into Congress in 1878 was overwhelmingly defeated.

In the 1880s it became clear that it was not a good idea to have two rival groups campaigning for votes for women. After several years of negotiations, the AWSA and the NWSA merged in 1890 to form the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA). The leaders of this new organisation include Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony, Mary Livermore, Carrie Chapman Catt, Olympia Brown, Amelia Bloomer, Frances Willard, Matilda Joslyn Gage and Anna Howard Shaw.

Over the next twenty years a large number of women became involved in the struggle for women's rights. This included Jane Addams, Crystal Eastman, Helen Keller, Emma Goldman, Rose Schneiderman, Ida Wells-Barnett, Inez Milholland, Nina Alexender, Cornelia Barnes, Blanche Ames, Edwina Dumm, Rose O'Neill, Fredrikke Palmer, Ida Proper, Lou Rogers, Mary Wilson Preston, Mary Sigsbee, Ellen Gates Starr, Mary McDowell, Edith Abbott, Grace Abbott, Alzina Stevens, Florence Kelley, Julia Lathrop, Alice Hamilton, Rheta Childe Dorr, Alice Beach Winter, Margaret Robins, Margaret Haley, Helen Marot, Agnes Nestor, Madeline Breckinridge, Sophonisba Breckinridge and Nell Brinkley.

Mary Church Terrell was another important figure in the suffrage movement. She argued: "The elective franchise is withheld from one half of its citizens, many of whom are intelligent, cultured, and virtuous, while it is unstintingly bestowed upon the other, some of whom are illiterate, debauched and vicious, because the word people, by an unparalleled exhibition of lexicographical acrobatics, has been turned and twisted to mean all who were shrewd and wise enough to have themselves born boys instead of girls, or who took the trouble to be born white instead of black."

Rheta Childe Dorr pointed out that this was a worldwide movement: "Not only in the United States, but in every constitutional country in the world the movement towards admitting women to full political equality with men is gathering strength. In half a dozen countries women are already completely enfranchised. In England the opposition is seeking terms of surrender. In the United States the stoutest enemy of the movement acknowledges that woman suffrage is ultimately inevitable. The voting strength of the world is about to be doubled, and the new element is absolutely an unknown quantity. Does anyone question that this is the most important political fact the modern world has ever faced?"

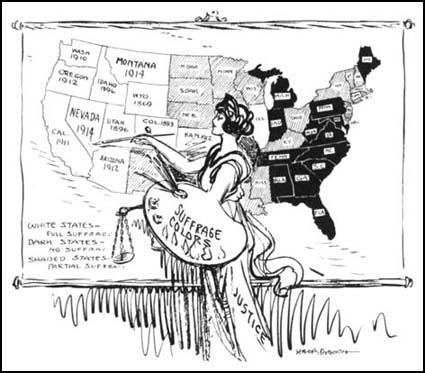

Working with journals such as the Women Voter, The Women's Journal, Woman Citizen and The Masses, the suffragists mounted vigorous campaigns to gain the vote. They tended to concentrate their energies in trying to persuade state legislatures to submit to their voters amendments to state constitutions conferring full suffrage to women. Individual states gradually yielded to these demands. In 1893 women got the vote in Colorado, followed by Utah (1896), Idaho (1896), Washington (1910), California (1911), Arizona (1912), Kansas (1912), Oregon (1912), Illinois (1913), Nevada (1914) and Montana (1914).

Maryland Suffrage News (14th November, 1914)

While studying at the School of Economics and Political Science (LSE) in London, Alice Paul, joined the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) and her activities resulted in her being arrested and imprisoned three times. Like other suffragettes she went on hunger strike and was forced-fed.

Paul returned home to the United States and in 1913 she joined with Lucy Burns and Olympia Brown to form the Congressional Union for Women Suffrage (CUWS) and attempted to introduce the militant methods used by the Women's Social and Political Union in Britain. This included organizing huge demonstrations and the daily picketing of the White House. Over the next couple of years the police arrested nearly 500 women for loitering and 168 were jailed for "obstructing traffic". Paul was sentenced to seven months imprisonment but after going on hunger strike she was released.

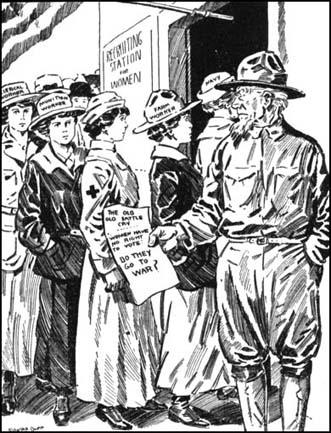

Columbus Daily Monitor (16th May, 1917)

After the United States joined the First World War, the protesters were continually assaulted by patriotic male bystanders, while picketing outside the White House. Arrested several times, Lucy Burns spent more time prison than any other American suffragist. Doris Stevens claimed that Burns became the most important figure in the militant campaign: "It fell to Lucy Burns, vice-chairman of the organization, to be the leader of the new protest. Miss Burns is in appearance the very symbol of woman in revolt. Her abundant and glorious red hair burns and is not consumed - a flaming torch.... Musical, appealing, persuading - she could move the most resistant person. Her talent as an orator is of the kind that makes for instant intimacy with her audience. Her emotional quality is so powerful that her intellectual capacity, which is quite as great, is not always at once perceived."

In January, 1918, Woodrow Wilson announced that women's suffrage was urgently needed as a "war measure". The House of Representatives passed the federal woman suffrage amendment 274 to 136 but it was opposed in the Senate and was defeated in September 1918. Another attempt in February 1919 also ended in failure.

In May 1919 the House of Representatives again passed the amendment (304 to 89) and on 4th June 1919 the Senate finally gave in and passed it by 66 to 30. On 26th August 1920 the Nineteenth Amendment was certified by the Secretary of State, when Tennessee, the thirty-sixth and final state needed, signed for ratification.

One of the campaigners, Crystal Eastman, argued: "The problem of women's freedom is how to arrange the world so that women can be human beings, with a chance to exercise their infinitely varied gifts in infinitely ways, instead of being destined by the accident of their sex to one field of activity - housework and child-raising. And second, if and when they choose housework and child-raising to have that occupation recognized by the world as work, requiring a definite economic reward and not merely entitling the performer to be dependent on some man. I can agree that women will never be great until they achieve a certain emotional freedom, a strong healthy egotism, and some unpersonal source of joy - that is this inner sense we cannot make women free by changing her economic status."

Primary Sources

(1) Margaret Fuller, Women in the Nineteenth Century (1845)

We would have every arbitrary barrier thrown down. We would have every path laid open to Woman as freely as to Man. Were this done, and a slight temporary fermentation allowed to subside, we should see crystallizations more pure and of more various beauty. We believe the divine energy would pervade nature to a degree unknown in the history of former ages, and that no discordant collision, but a ravishing harmony of the spheres, would ensue.

Yet, then and only then will mankind be ripe for this, when inward and outward freedom for Woman as much as for Man shall be acknowledged as a right, not yielded as a concession. As the friend of the Negro assumes that one man cannot by right hold another in bondage, so should the friend of Woman assume that Man cannot by right lay even well meant restrictions on Woman. If the Negro be a soul, if the woman be a soul, apparelled in flesh, to one Master only are they accountable. There is but one law for souls, and, if there is to be an interpreter of it, he must come not as man, or son of man, but as son of God.

Were thought and feeling once so far elevated that Man should esteem himself the brother and friend, but nowise the lord and tutor, of Woman, - were he really bound with her in equal worship, - arrangements as to function and employment would be of no consequence. What woman needs is not as a woman to act or rule, but as a nature to grow, as an intellect to discern, as a soul to live freely and unimpeded, to unfold such powers as were given her when we left our common home. If fewer talents were given her, yet if allowed the free and full employment of these, so that she may render back to the giver his own with usury, she will not complain; nay, I dare to say she will bless and rejoice in her earthly birthplace, her earthly lot.

(2) Samuel J. May, The Rights and Condition of Women (1846)

To prove, however, that woman was not intended to be the equal of man, the argument most frequently alleged is that she is the weaker vessel, inferior in stature, and has much less physical strength. This physiological fact, of course, cannot be denied; although the disparity in these respects is very much increased by neglect or mismanagement. But allowing women generally to have less bodily power, why should this consign them to mental, moral, or social dependence? Physical force is of special value only in a savage or barbarous community. It is the avowed intention and tendency of Christianity to give the ascendancy to man's moral nature; and the promises of God, with whom is all strength and wisdom, are to the upright, the pure, the good, not to the strong, the valiant, or the crafty.

The more men receive of the lessons of Christianity, the more they learn to trust in God, in the might of the right and true, the less reliance will they put upon brute force. And as brute force declines in public estimation, the more will the feminine qualities of the human race rise in general regard and confidence, until the meek shall be seen to be better than the mighty, and the humble only be considered worthy of exaltation. Civilization implies the subordination of the physical in man to the mental and moral; and the progress of the melioration of the condition of our race has been everywhere marked by the elevation of the female sex.

But some would eagerly ask, should women be allowed to take part in the constructing and administering of our civil institutions? Allowed, do you say? The very form of the question is an assumption of the right to do them the wrong that has been done them. Allowed! Why, pray tell me, is it from us their rights have been received? Have we the authority to accord to them just such prerogatives as we see fit and withhold the rest? No! woman is not the creature, the dependent of man but of God. We may with no more propriety assume to govern women than they might assume to govern us. And never will the nations of the earth be well-governed until both sexes, as well as all parties, are fairly represented and have an influence, a voice, and, if they wish, a hand in the enactment and administration of the laws.

One would think the sad mismanagement of the affairs of our own country should, in all modesty, lead us men to doubt our own capacity for the task of governing a nation, or even a state, alone; and to apprehend that we need other qualities in our public councils, qualities that may be found in the female portion of our race. If woman be the complement of man, we may surely venture the intimation that all our social transactions will be incomplete, or otherwise imperfect, unless they have been guided alike by the wisdom of each sex. The wise, virtuous, gentle mothers of a state or nation (should their joint influence be allowed) might contribute as much to the good order, the peace, the thrift of the body politic as they severally do to the well-being of their families, which for the most part, all know is more than the fathers do.

(3) John Humphrey Noyes, wrote about Fanny Wright in his book, History of American Socialism (1870)

Frances Wright, little known to the present generation, was really the spiritual helpmate and better half of the Owens, in the socialistic revival of 1826. Our impression is, not only that she was the leading woman in the communistic movement of that period, but that she had a very important agency in starting two other movements that had far greater success and are at this moment in popular favour: anti-slavery and woman's rights.

(4) Ernestine L. Rose, speech on Fanny Wright at the National Woman's Rights Convention (1858)

Frances Wright was the first woman in this country who spoke on the equality of the sexes. She had indeed a hard task before her. The elements were entirely unprepared. She had to break up the time-hardened soil of conservatism, and her reward was sure - the same reward that is always bestowed upon those who are in the vanguard of any great movement. She was subjected to public odium, slander, and persecution. But these were not the only things she received. Oh, she had her reward - that reward of which no enemies could deprive her, which no slanders could make less precious - the eternal reward of knowing that she had done her duty.

(5) Mary Church Terrell, The Washington Post (10th February, 1900)

The elective franchise is withheld from one half of its citizens, many of whom are intelligent, cultured, and virtuous, while it is unstintingly bestowed upon the other, some of whom are illiterate, debauched and vicious, because the word people, by an unparalleled exhibition of lexicographical acrobatics, has been turned and twisted to mean all who were shrewd and wise enough to have themselves born boys instead of girls, or who took the trouble to be born white instead of black.

(6) Jane Addams, Ladies Home Journal (January, 1910)

Women who live in the country sweep their own dooryards and may either feed the refuse of the table to a flock of chickens or allow it innocently to decay in the open air and sunshine. In a crowded city quarter, however, if the street is not cleaned by the city authorities no amount of private sweeping will keep the tenement free from grime; if the garbage is not properly collected and destroyed a tenement house may see her children sicken and die of diseases from which she alone is powerless to shield them, although her tenderness and devotion are unbounded. In short, if women would keep on with her old business of caring for her house and rearing her children she will have to have some conscience in regard to public affairs lying quite outside of her immediate household. The individual conscience and devotion are no longer effective. The statement is sometimes made that the franchise for women would be valuable only so far as the educated women exercised it. This statement totally disregards the fact those those matters in which women's judgement is most needed are far too primitive and basic to be largely influenced by what we call education.

(7) Rheta Childe Dorr, What Eight Million Women Want (1910)

Not only in the United States, but in every constitutional country in the world the movement towards admitting women to full political equality with men is gathering strength. In half a dozen countries women are already completely enfranchised. In England the opposition is seeking terms of surrender. In the United States the stoutest enemy of the movement acknowledges that woman suffrage is ultimately inevitable. The voting strength of the world is about to be doubled, and the new element is absolutely an unknown quantity. Does anyone question that this is the most important political fact the modern world has ever faced?

I have asked you to consider three facts, but in reality they are but three manifestations of one fact, to my mind the most important human fact society has yet encountered. Women have ceased to exist as a subsidiary class in the community. They are no longer wholly dependent, economically, intellectually, and spiritually, on a ruling class of men. They look on life with the eyes of reasoning adults, where once they regarded it as trusting children. Women now form a new social group, separate, and to a degree homogeneous. Already they have evolved a group opinion and a group ideal.

And this brings me to my reason for believing that society will soon be compelled to make a serious survey of the opinions and ideals of women. As far as these have found collective expressions, it is evident that they differ very radically from accepted opinions and ideals of men. As a matter of fact, it is inevitable that this should be so. Back of the differences between the masculine and the feminine ideal lie centuries of different habits, different duties, different ambitions, different opportunities, different rewards.

Women, since society became an organized body, have been engaged in the rearing, as well as the bearing of children. They have made the home, they have cared for the sick, ministered to the aged, and given to the poor. The universal destiny of the mass of women trained them to feed and clothe, to invent, manufacture, build, repair, contrive, conserve, economize. They lived lives of constant service, within the narrow confines of a home. Their labor was given to those they loved, and the reward they looked for was purely a spiritual reward.

A thousand generations of service, unpaid, loving, intimate, must have left the strongest kind of a mental habit in its wake. Women, when they emerged from the seclusion of their homes and began to mingle in the world procession, when they were thrown on their own financial responsibility, found themselves willy-nilly in the ranks of the producers, the wage earners; when the enlightenment of education was no longer denied them, when their responsibilities ceased to be entirely domestic and became somewhat social, when, in a word, women began to think, they naturally thought in human terms. They couldn't have thought otherwise if they had tried.

(8) William Du Bois, The Crisis (October, 1911)

Every argument for Negro suffrage is an argument for women's suffrage; every argument for women's suffrage is an argument for Negro suffrage; both are great moments in democracy. There should be on the part of Negroes absolutely no hesitation whenever and wherever responsible human beings are without voice in their government. The man of Negro blood who hesitates to do them justice is false to his race, his ideals and his country.

(9) Leaflet written and distributed by Alice Paul outside of the White House in 1917.

President Wilson and Envoy Root are deceiving Russia. They say "We are a democracy. Help us to win the war so that democracies may survive." We women of America tell you that America is not a democracy. Twenty million women are denied the right to vote. President Wilson is the chief opponent of their national enfranchisement. Help us make this nation really free. Tell our government that it must liberate its people before it can claim free Russia as an ally.

(10) Alice Paul, letter to Doris Stevens (November, 1917)

At night, in the early morning, all through the day there were cries and shrieks and moans from the patients. It was terrifying. One particularly meloncholy moan used to keep up hour after hour with the regularity of a heart beat. I said to myself, "Now I have to endure this. I have got to live through this somehow. I pretend these moans are the noise of an elevated train, beginning faintly in the distance and getting louder as it comes nearer." Such childish devices were helpful to me.

(11) Woodrow Wilson, speech in Congress reported in the New York Times (1st October, 1918)

I regard the extension of suffrage to women as vitally essential to the successful prosecution of the great war of humanity in which we are engaged. It is my duty to win the war and to ask you to remove every obstacle that stands in the way of winning it. They (other nations) are looking to the great, powerful, famous democracy of the West to lead them to a new day for which they have long waited; and they think in their logical simplicity that democracy means that women shall play their part in affairs alongside men and upon an equal footing with them. I tell you plainly as the Commander-in-Chief of our armies that this measure is vital to the winning of the war.

(12) Crystal Eastman, Now We Can Begin (December, 1920)

The problem of women's freedom is how to arrange the world so that women can be human beings, with a chance to exercise their infinitely varied gifts in infinitely ways, instead of being destined by the accident of their sex to one field of activity - housework and child-raising. And second, if and when they choose housework and child-raising to have that occupation recognized by the world as work, requiring a definite economic reward and not merely entitling the performer to be dependent on some man. I can agree that women will never be great until they achieve a certain emotional freedom, a strong healthy egotism, and some unpersonal source of joy - that is this inner sense we cannot make women free by changing her economic status.

Student Activities

Economic Prosperity in the United States: 1919-1929

Women in the United States in the 1920s

Subjects