1905 Russian Revolution

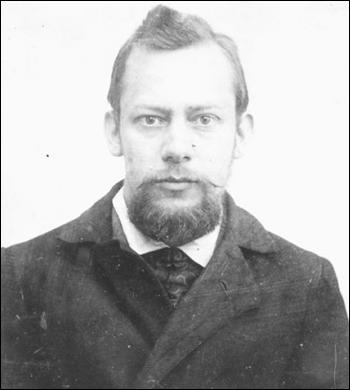

1904 was a bad year for Russian workers. Prices of essential goods rose so quickly that real wages declined by 20 per cent. When four members of the Assembly of Russian Workers were dismissed at the Putilov Iron Works in December, Gapon tried to intercede for the men who lost their jobs. This included talks with the factory owners and the governor-general of St Petersburg. When this failed, Gapon called for his members in the Putilov Iron Works to come out on strike. (1)

Father Georgi Gapon demanded: (i) An 8-hour day and freedom to organize trade unions. (ii) Improved working conditions, free medical aid, higher wages for women workers. (iii) Elections to be held for a constituent assembly by universal, equal and secret suffrage. (iv) Freedom of speech, press, association and religion. (v) An end to the war with Japan. By the 3rd January 1905, all 13,000 workers at Putilov were on strike, the department of police reported to the Minister of the Interior. "Soon the only occupants of the factory were two agents of the secret police". (2)

The strike spread to other factories. By the 8th January over 110,000 workers in St. Petersburg were on strike. Father Gapon wrote that: "St Petersburg seethed with excitement. All the factories, mills and workshops gradually stopped working, till at last not one chimney remained smoking in the great industrial district... Thousands of men and women gathered incessantly before the premises of the branches of the Workmen's Association." (3)

Tsar Nicholas II became concerned about these events and wrote in his diary: "Since yesterday all the factories and workshops in St. Petersburg have been on strike. Troops have been brought in from the surroundings to strengthen the garrison. The workers have conducted themselves calmly hitherto. Their number is estimated at 120,000. At the head of the workers' union some priest - socialist Gapon. Mirsky (the Minister of the Interior) came in the evening with a report of the measures taken." (4)

Gapon drew up a petition that he intended to present a message to Nicholas II: "We workers, our children, our wives and our old, helpless parents have come, Lord, to seek truth and protection from you. We are impoverished and oppressed, unbearable work is imposed on us, we are despised and not recognized as human beings. We are treated as slaves, who must bear their fate and be silent. We have suffered terrible things, but we are pressed ever deeper into the abyss of poverty, ignorance and lack of rights." (5)

The petition contained a series of political and economic demands that "would overcome the ignorance and legal oppression of the Russian people". This included demands for universal and compulsory education, freedom of the press, association and conscience, the liberation of political prisoners, separation of church and state, replacement of indirect taxation by a progressive income tax, equality before the law, the abolition of redemption payments, cheap credit and the transfer of the land to the people. (6)

Bloody Sunday

Over 150,000 people signed the document and on 22nd January, 1905, Father Georgi Gapon led a large procession of workers to the Winter Palace in order to present the petition. The loyal character of the demonstration was stressed by the many church icons and portraits of the Tsar carried by the demonstrators. Alexandra Kollontai was on the march and her biographer, Cathy Porter, has described what took place: "She described the hot sun on the snow that Sunday morning, as she joined hundreds of thousands of workers, dressed in their Sunday best and accompanied by elderly relatives and children. They moved off in respectful silence towards the Winter Palace, and stood in the snow for two hours, holding their banners, icons and portraits of the Tsar, waiting for him to appear." (7)

Harold Williams, a journalist working for the Manchester Guardian, also watched the Gapon led procession taking place: "I shall never forget that Sunday in January 1905 when, from the outskirts of the city, from the factory regions beyond the Moscow Gate, from the Narva side, from up the river, the workmen came in thousands crowding into the centre to seek from the tsar redress for obscurely felt grievances; how they surged over the snow, a black thronging mass." (8) The soldiers machine-gunned them down and the Cossacks charged them. (9)

Alexandra Kollontai observed the "trusting expectant faces, the fateful signal of the troops stationed around the Palace, the pools of blood on the snow, the bellowing of the gendarmes, the dead, the wounded, the children shot." She added that what the Tsar did not realise was that "on that day he had killed something even greater, he had killed superstition, and the workers' faith that they could ever achieve justice from him. From then on everything was different and new." (10) It is not known the actual numbers killed but a public commission of lawyers after the event estimated that approximately 150 people lost their lives and around 200 were wounded. (11)

Gapon later described what happened in his book The Story of My Life (1905): "The procession moved in a compact mass. In front of me were my two bodyguards and a yellow fellow with dark eyes from whose face his hard labouring life had not wiped away the light of youthful gaiety. On the flanks of the crowd ran the children. Some of the women insisted on walking in the first rows, in order, as they said, to protect me with their bodies, and force had to be used to remove them. Suddenly the company of Cossacks galloped rapidly towards us with drawn swords. So, then, it was to be a massacre after all! There was no time for consideration, for making plans, or giving orders. A cry of alarm arose as the Cossacks came down upon us. Our front ranks broke before them, opening to right and left, and down the lane the soldiers drove their horses, striking on both sides. I saw the swords lifted and falling, the men, women and children dropping to the earth like logs of wood, while moans, curses and shouts filled the air." (12)

Alexandra Kollontai observed the "trusting expectant faces, the fateful signal of the troops stationed around the Palace, the pools of blood on the snow, the bellowing of the gendarmes, the dead, the wounded, the children shot." She added that what the Tsar did not realise was that "on that day he had killed something even greater, he had killed superstition, and the workers' faith that they could ever achieve justice from him. From then on everything was different and new." It is not known the actual numbers killed but a public commission of lawyers after the event estimated that approximately 150 people lost their lives and around 200 were wounded. (13)

Father Gapon escaped uninjured from the scene and sought refuge at the home of Maxim Gorky: "Gapon by some miracle remained alive, he is in my house asleep. He now says there is no Tsar anymore, no church, no God. This is a man who has great influence upon the workers of the Putilov works. He has the following of close to 10,000 men who believe in him as a saint. He will lead the workers on the true path." (14)

1905 Russian Revolution

The killing of the demonstrators became known as Bloody Sunday and it has been argued that this event signalled the start of the 1905 Revolution. That night the Tsar wrote in his diary: "A painful day. There have been serious disorders in St. Petersburg because workmen wanted to come up to the Winter Palace. Troops had to open fire in several places in the city; there were many killed and wounded. God, how painful and sad." (15)

The massacre of an unarmed crowd undermined the standing of the autocracy in Russia. The United States consul in Odessa reported: "All classes condemn the authorities and more particularly the Tsar. The present ruler has lost absolutely the affection of the Russian people, and whatever the future may have in store for the dynasty, the present tsar will never again be safe in the midst of his people." (16)

The day after the massacre all the workers at the capital's electricity stations came out on strike. This was followed by general strikes taking place in Moscow, Vilno, Kovno, Riga, Revel and Kiev. Other strikes broke out all over the country. Pyotr Sviatopolk-Mirsky resigned his post as Minister of the Interior, and on 19th January, 1905, Tsar Nicholas II summoned a group of workers to the Winter Palace and instructed them to elect delegates to his new Shidlovsky Commission, which promised to deal with some of their grievances. (17)

Lenin, who had been highly suspicious of Father Gapon, admitted that the formation of Assembly of Russian Workers of St Petersburg and the occurrence of Bloody Sunday, had made an important contribution to the development of a radical political consciousness: "The revolutionary education of the proletariat made more progress in one day than it could have made in months and years of drab, humdrum, wretched existence." (18)

Henry Nevinson, of The Daily Chronicle commented that Gapon was "the man who struck the first blow at the heart of tyranny and made the old monster sprawl." When he heard the news of Bloody Sunday Leon Trotsky decided to return to Russia. He realised that Father Gapon had shown the way forward: "Now no one can deny that the general strike is the most important means of fighting. The twenty-second of January was the first political strike, even if he was disguised under a priest's cloak. One need only add that revolution in Russia may place a democratic workers' government in power." (19)

Trotsky believed that Bloody Sunday made the revolution much more likely. One revolutionary noted that the killing of peaceful protestors had changed the political views of many peasants: "Now tens of thousands of revolutionary pamphlets were swallowed up without remainder; nine-tenths were not only read but read until they fell apart. The newspaper which was recently considered by the broad popular masses, and particularly by the peasantry, as a landlord's affair, and when it came accidentally into their hands was used in the best of cases to roll cigarettes in, was now carefully, even lovingly, straightened and smoothed out, and given to the literate." (20)

Assassination of Sergei Alexandrovich

The SR Combat Organization decided the next man to be assassinated was the Grand Duke Sergei Alexandrovich. the General-Governor of Moscow and uncle of Tsar Nicholas II. The assassination was planned for 15th February, 1905, when he planned to visit the Bolshoi Theatre. (21) Ivan Kalyayev was supposed to attack the carriage as it approached the theater. Kalyayev was about to throw his bomb at the carriage of the Grand Duke, but he noticed that his wife and two young children were in the carriage and he aborted the assassination. (22)

Ivan Kalyayev carried out the assassination two days later: "I hurled my bomb from a distance of four paces, not more, striking as I dashed forward quite close to my object. I was caught up by the storm of the explosion and saw how the carriage was torn to fragments. When the cloud had lifted I found myself standing before the remains of the back wheels.... Then, about five feet away, near the gate, I saw bits of the Grand Duke's clothing and his nude body.... Blood was streaming from my face, and I realized there would be no escape for me.:.. I was overtaken by the police agents in a sleigh and someone's hands were upon me. 'Don't hang on to me. I won't run away. I have done my work' (I realized now that I was deafened)." (23)

While he was in prison he was visited by the Grand Duke's wife. She asked him "Why did you kill my husband?". He replied "I killed Sergei Alexandrovich because he was a weapon of tyranny. I was taking revenge for the people." The Grand Duchess offered Kalyayev a deal. "Repent... and I will beg the Sovereign to give you your life. I will ask him for you. I myself have already forgiven you." He refused with the words: "'No! I do not repent. I must die for my deed and I will... My death will be more useful to my cause than Sergei Alexandrovich's death." (24)

During his trial Kalyayev defended his actions: "First of all, permit me to make a correction of fact: I am not a defendant here, I am your prisoner. We are two warring camps. You - the representatives of the Imperial Government, the hired servants of capital and oppression. I - one of the avengers of the people, a socialist and revolutionist. Mountains of corpses divide us, hundreds of thousands of broken human lives and a whole sea of blood and tears covering the country in torrents of horror and resentment. You have declared war on the people. We have accepted your challenge." (25)

Ivan Kalyayev was sentenced to death. "I am pleased with your sentence," he told the judges. "I hope that you will carry it out just as openly and publicly as I carried out the sentence of the Socialist Revolutionary Party. Learn to look the advancing revolution right in the face." He was hanged on 23rd May, 1905. (26)

Death of Father Gapon

After the massacre Father Georgi Gapon left Russia and went to live in Geneva. Bloody Sunday made Father Gapon a national figure overnight and he enjoyed greater popularity "than any Russian revolutionary had previously commanded". (27) One of the first people he met was George Plekhanov, the leader of the Mensheviks. (28)

Plekhanov introduced Gapon to Pavel Axelrod, Vera Zasulich, Lev Deich and Fedor Dan. Gapon told them that he fully shared the views of this revolutionary group and this information was published in the Menshevik's newspaper, Vorwärts. Deich later recalled that they made efforts to give him an education in Marxism. They explained that the course of history was determined by objective historical laws, not by individual actions. Gapon also went to live with Axelrod. (29)

Victor Adler sent Leon Trotsky a telegram after receiving a message from Pavel Axelrod. "I have just received a telegram from Axelrod saying that Gapon has arrived abroad and announced himself as a revolutionary. It's a pity. If he had disappeared altogether there would have remained a beautiful legend, whereas as an emigre he will be a comical figure. You know, such men are better as historical martyrs than as comrades in a party." (30)

The leaders of the Socialist Revolutionary Party (SRP) became upset by this development and used his friend, Pinchas Rutenberg, to try and get him to change his mind. Rutenberg received instructions "to make every effort to win him over". This included persuading him to live with SRP supporter, Leonid E. Shishko. "By inclination and temperament, Gapon was more at home with the Socialist Revolutionaries, who emphasized the force of individual action and revolutionary voluntarism." (31)

Father Gapon saw himself as the leader of the coming revolution and believed that his first task was to unify the revolutionary parties. However, he preferred the SRP approach to politics. He told Lev Deich: "Theories are not important to them, only that the person possesses courage and be devoted to the people's cause. They do not demand anything from me, do not criticize my actions. On the contrary, they always praise me." (32)

Victor Chernov was not convinced that Gapon really supported the SRP: "A party man, no matter what party, Gapon never was, nor was he capable of being one... Even if Gapon genuinely intended to follow a certain line of behavior, he could not do so. He would violate this promise, as he violated every promise he made to himself. At the first opportunity he would find it more tactically advantageous to act in a different manner. If you want, he was a complete and absolute anarchist, incapable of being a regular party member. Every organization he could conceive was only a superstructure of his unlimited authority. He alone had to be in the center of everything, know everything, hold in his hands the strings of the organization and manipulate the people tied to them in whatever manner he saw fit." (33)

Father Georgi Gapon also had meetings with the anarchist, Peter Kropotkin. He also had conversations with Lenin and other Bolsheviks in Geneva. (34) Nadezhda Krupskaya reported: "In Geneva Gapon began to visit us frequently. He talked a lot. Vladimir Il'ich listened attentively, trying to discern in his accounts the features of the approaching revolution". Lenin's conversations with Gapon helped persuade him to alter the Bolshevik agrarian policy. (35)

Gapon's common law wife joined him in exile and in May, 1905, they visited London. He was offered a considerable sum from a publisher to write his autobiography, The Story of My Life (1905). While in the England he was asked to write an appeal against anti-Semitism. He readily agreed and wrote a pamphlet against Jewish pogroms, and refused to accept a share of the royalties offered him. (36)

Sergei Witte and the October Manifesto

In June, 1905, Sergei Witte was asked to negotiate an end to the Russo-Japanese War. The Nicholas II was pleased with his performance and was brought into the government to help solve the industrial unrest that had followed Bloody Sunday. Witte pointed out: "With many nationalities, many languages and a nation largely illiterate, the marvel is that the country can be held together even by autocracy. Remember one thing: if the tsar's government falls, you will see absolute chaos in Russia, and it will be many a long year before you see another government able to control the mixture that makes up the Russian nation." (37)

Emile J. Dillon, a journalist working for the Daily Telegraph, agreed with Witte's analysis: "Witte... convinced me that any democratic revolution, however peacefully effected, would throw open the gates wide to the forces of anarchism and break up the empire. And a glance at the mere mechanical juxtaposition - it could not be called union - of elements so conflicting among themselves as were the ethnic, social and religious sections and divisions of the tsar's subjects would have brought home this obvious truth to the mind of any unbiased and observant student of politics." (38)

On 27th June, 1905, sailors on the Potemkin battleship, protested against the serving of rotten meat infested with maggots. The captain ordered that the ringleaders to be shot. The firing-squad refused to carry out the order and joined with the rest of the crew in throwing the officers overboard. The mutineers killed seven of the Potemkin's eighteen officers, including Captain Evgeny Golikov. They organized a ship's committee of 25 sailors, led by Afanasi Matushenko, to run the battleship. (39)

A delegation of the mutinous sailors arrived in Geneva with a message addressed directly to Father Gapon. He took the cause of the sailors to heart and spent all his time collecting money and purchasing supplies for them. He and their leader, Afanasi Matushenko, became inseparable. "Both were of peasant origin and products of the mass upheaval of 1905 - both were out of place among the party intelligentsia of Geneva." (40)

The Potemkin Mutiny spread to other units in the army and navy. Industrial workers all over Russia withdrew their labour and in October, 1905, the railwaymen went on strike which paralyzed the whole Russian railway network. This developed into a general strike. Leon Trotsky later recalled: "After 10th October 1905, the strike, now with political slogans, spread from Moscow throughout the country. No such general strike had ever been seen anywhere before. In many towns there were clashes with the troops." (41)

Sergei Witte, his Chief Minister, saw only two options open to the Tsar Nicholas II; "either he must put himself at the head of the popular movement for freedom by making concessions to it, or he must institute a military dictatorship and suppress by naked force for the whole of the opposition". However, he pointed out that any policy of repression would result in "mass bloodshed". His advice was that the Tsar should offer a programme of political reform. (42)

On 22nd October, 1905, Sergei Witte sent a message to the Tsar: "The present movement for freedom is not of new birth. Its roots are imbedded in centuries of Russian history. Freedom must become the slogan of the government. No other possibility for the salvation of the state exists. The march of historical progress cannot be halted. The idea of civil liberty will triumph if not through reform then by the path of revolution. The government must be ready to proceed along constitutional lines. The government must sincerely and openly strive for the well-being of the state and not endeavour to protect this or that type of government. There is no alternative. The government must either place itself at the head of the movement which has gripped the country or it must relinquish it to the elementary forces to tear it to pieces." (43)

Nicholas II became increasingly concerned about the situation and entered into talks with Sergi Witte. As he pointed out: "Through all these horrible days, I constantly met Witte. We very often met in the early morning to part only in the evening when night fell. There were only two ways open; to find an energetic soldier and crush the rebellion by sheer force. That would mean rivers of blood, and in the end we would be where had started. The other way out would be to give to the people their civil rights, freedom of speech and press, also to have laws conformed by a State Duma - that of course would be a constitution. Witte defends this very energetically." (44)

Grand Duke Nikolai Romanov, the second cousin of the Tsar, was an important figure in the military. He was highly critical of the way the Tsar dealt with these incidents and favoured the kind of reforms favoured by Sergi Witte: "The government (if there is one) continues to remain in complete inactivity... a stupid spectator to the tide which little by little is engulfing the country." (45)

On 22nd October, 1905, Sergi Witte sent a message to the Tsar: "The present movement for freedom is not of new birth. Its roots are imbedded in centuries of Russian history. Freedom must become the slogan of the government. No other possibility for the salvation of the state exists. The march of historical progress cannot be halted. The idea of civil liberty will triumph if not through reform then by the path of revolution. The government must be ready to proceed along constitutional lines. The government must sincerely and openly strive for the well-being of the state and not endeavour to protect this or that type of government. There is no alternative. The government must either place itself at the head of the movement which has gripped the country or it must relinquish it to the elementary forces to tear it to pieces." (46)

Later that month, Trotsky and other Mensheviks established the St. Petersburg Soviet. On 26th October the first meeting of the Soviet took place in the Technological Institute. It was attended by only forty delegates as most factories in the city had time to elect the representatives. It published a statement that claimed: "In the next few days decisive events will take place in Russia, which will determine for many years the fate of the working class in Russia. We must be fully prepared to cope with these events united through our common Soviet." (47)

Over the next few weeks over 50 of these soviets were formed all over Russia and these events became known as the 1905 Revolution. Witte continued to advise the Tsar to make concessions. The Grand Duke Nikolai Romanov agreed and urged the Tsar to bring in reforms. The Tsar refused and instead ordered him to assume the role of a military dictator. The Grand Duke drew his pistol and threatened to shoot himself on the spot if the Tsar did not endorse Witte's plan. (48)

On 30th October, the Tsar reluctantly agreed to publish details of the proposed reforms that became known as the October Manifesto. This granted freedom of conscience, speech, meeting and association. He also promised that in future people would not be imprisoned without trial. Finally it announced that no law would become operative without the approval of the State Duma. It has been pointed out that "Witte sold the new policy with all the forcefulness at his command". He also appealed to the owners of the newspapers in Russia to "help me to calm opinions". (49)

Primary Sources

(1) Father Georgi Gapon, letter to Nicholas II (21st January, 1905)

The people believe in thee. They have made up their minds to gather at the Winter Palace tomorrow at 2 p.m. to lay their needs before thee. Do not fear anything. Stand tomorrow before the party and accept our humblest petition. I, the representative of the workingmen, and my comrades, guarantee the inviolability of thy person.

(2) Tsar Nicholas II, diary entry (21st January, 1917)

Since yesterday all the factories and workshops in St. Petersburg have been on strike. Troops have been brought in from the surroundings to strengthen the garrison. The workers have conducted themselves calmly hitherto. Their number is estimated at 120,000. At the head of the workers' union some priest - socialist Gapon. Mirsky came in the evening with a report of the measures taken.

(3) Extract from the petition that Father Georgi Gapon hoped to present to Nicholas II on 22nd January, 1905.

We workers, our children, our wives and our old, helpless parents have come, Lord, to seek truth and protection from you. We are impoverished and oppressed, unbearable work is imposed on us, we are despised and not recognized as human beings. We are treated as slaves, who must bear their fate and be silent. We have suffered terrible things, but we are pressed ever deeper into the abyss of poverty, ignorance and lack of rights.

(4) The demands made by Father Georgi Gapon and the Assembly of Russian Workers.

(1) An 8-hour day and freedom to organize trade unions.

(2) Improved working conditions, free medical aid, higher wages for women workers.

(3) Elections to be held for a constituent assembly by universal, equal and secret suffrage.

(4) Freedom of speech, press, association and religion.

(5) An end to the war with Japan.

(5) Father Georgi Gapon, The Story of My Life (1905)

The procession moved in a compact mass. In front of me were my two bodyguards and a yellow fellow with dark eyes from whose face his hard labouring life had not wiped away the light of youthful gaiety. On the flanks of the crowd ran the children. Some of the women insisted on walking in the first rows, in order, as they said, to protect me with their bodies, and force had to be used to remove them.

Suddenly the company of Cossacks galloped rapidly towards us with drawn swords. So, then, it was to be a massacre after all! There was no time for consideration, for making plans, or giving orders. A cry of alarm arose as the Cossacks came down upon us. Our front ranks broke before them, opening to right and left, and down the lane the soldiers drove their horses, striking on both sides. I saw the swords lifted and falling, the men, women and children dropping to the earth like logs of wood, while moans, curses and shouts filled the air.

Again we started forward, with solemn resolution and rising rage in our hearts. The Cossacks turned their horses and began to cut their way through the crowd from the rear. They passed through the whole column and galloped back towards the Narva Gate, where - the infantry having opened their ranks and let them through - they again formed lines.

We were not more than thirty yards from the soldiers, being separated from them only by the bridge over the Tarakanovskii Canal, which here masks the border of the city, when suddenly, without any warning and without a moment's delay, was heard the dry crack of many rifle-shots. Vasiliev, with whom I was walking hand in hand, suddenly left hold of my arm and sank upon the snow. One of the workmen who carried the banners fell also. Immediately one of the two police officers shouted out "What are you doing? How dare you fire upon the portrait of the Tsar?"

An old man named Lavrentiev, who was carrying the Tsar's portrait, had been one of the first victims. Another old man caught the portrait as it fell from his hands and carried it till he too was killed by the next volley. With his last gasp the old man said "I may die, but I will see the Tsar".

Both the blacksmiths who had guarded me were killed, as well as all these who were carrying the ikons and banners; and all these emblems now lay scattered on the snow. The soldiers were actually shooting into the courtyards at the adjoining houses, where the crowd tried to find refuge and, as I learned afterwards, bullets even struck persons inside, through the windows.

At last the firing ceased. I stood up with a few others who remained uninjured and looked down at the bodies that lay prostrate around me. Horror crept into my heart. The thought flashed through my mind, And this is the work of our Little Father, the Tsar". Perhaps the anger saved me, for now I knew in very truth that a new chapter was opened in the book of history of our people.

(6) Tsar Nicholas II, diary entry (22nd January, 1917)

A painful day. There have been serious disorders in St. Petersburg because workmen wanted to come up to the Winter Palace. Troops had to open fire in several places in the city; there were many killed and wounded. God, how painful and sad.

(7) Victor Serge, Year One of the Russian Revolution (1930)

Gapon is a remarkable character. He seems to have believed sincerely in the possibility of reconciling the true interests of the workers with the authorities' good intentions. At any rate it was he who organized the movement to petition the Tsar which ended with the massacre of 22 January, 1905.

The petition of the workers of St. Petersburg on Nicholas II, drafted by Gapon and endorsed by tens of thousands of proletarians, was both a lugubrious entreaty and a daring set of demands. It asked for an eight-hour day, recognition of workers' rights and a Constitution (including the responsibility of ministers to the people, separation of Church and State, and democratic liberties). From all quarters of the capital the petitioners, carrying icons and singing hymns, set off marching through the snow, late on a January morning, to see their "little father, the Tsar".

At every cross-road armed ambushes were waiting for them. The soldiers machine-gunned them down and the Cossacks charged them. "Treat them like rebels" had been the Emperor's command. The outcome of the day was several hundred dead and as many wounded. This stupid and criminal repression detonated the first Russian revolution.

Student Activities

Russian Revolution Simmulation

Bloody Sunday (Answer Commentary)

1905 Russian Revolution (Answer Commentary)

Russia and the First World War (Answer Commentary)

The Life and Death of Rasputin (Answer Commentary)

The Coal Industry: 1600-1925 (Answer Commentary)

Women in the Coalmines (Answer Commentary)

Child Labour in the Collieries (Answer Commentary)

Child Labour Simulation (Teacher Notes)

The Chartists (Answer Commentary)

Women and the Chartist Movement (Answer Commentary)

Road Transport and the Industrial Revolution (Answer Commentary)

Canal Mania (Answer Commentary)

Early Development of the Railways (Answer Commentary)

Health Problems in Industrial Towns (Answer Commentary)

Public Health Reform in the 19th century (Answer Commentary)

Richard Arkwright and the Factory System (Answer Commentary)

Robert Owen and New Lanark (Answer Commentary)

James Watt and Steam Power (Answer Commentary)

The Domestic System (Answer Commentary)

The Luddites: 1775-1825 (Answer Commentary)

The Plight of the Handloom Weavers (Answer Commentary)

1832 Reform Act and the House of Lords (Answer Commentary)

Benjamin Disraeli and the 1867 Reform Act (Answer Commentary)

William Gladstone and the 1884 Reform Act (Answer Commentary)