Victor Serge

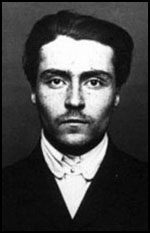

Victor Kibalchich (he later took the name Victor Serge), the son of Russian Polish parents, was born in Belgium in 1890. His father, an officer in the Imperial Guard, was a member of the Land and Liberty group and was related to Nikolai Kibalchich of the People's Will. After the arrest of Kibalchich as a result of the assassination of Alexander II in 1881, Serge's father fled the country. He eventually found work as a teacher at the Institute of Anatomy in Brussels.

His father introduced Serge to the writings of Alexander Herzen, Nikolai Chernyshevsky and Vissarion Belinsky: "He (his father) intended to become a physician, but geology, chemistry, sociology, and philosophy also interested him passionately. I never knew him as anything but a man possessed with an insatiable thirst for knowledge and understanding, which was to handicap him during all his remaining years."

Serge wrote in his autobiography, Memoirs of a Revolutionary (1951): "Even before I emerged from childhood, I seem to have experienced, deeply at heart, that paradoxical feeling which was to dominate me all through the first part of my life: that of living in a world without any possible escape, in which there was nothing for it but to fight for an impossible escape. I felt repugnance, mingled with wrath and indignation, towards people whom I saw settled comfortably in this world. How could they not be conscious of their captivity, of their unrighteousness? All this was a result, as I can see today, of my upbringing as the son of revolutionary exiles, tossed into the great cities of the West by the first political hurricanes blowing over Russia."

Brussels Revolutionary Gang

Victor Serge read a great deal and was influenced by the political theories of Peter Lavrov, Élisée Reclus and Peter Kropotkin. In Brussels in 1906 he became friends with a group of anarchists that included Jean de Boe, Raymond Callemin, Octave Garnier, René Valet and Edouard Carouy. The group became known as the Brussels Revolutionary Gang. He later wrote: "Anarchism swept us away completely because it both demanded everything of us and offered us everything. There was no corner of life that it failed to illumine; at least so it seemed to us...Shot through with contradictions, fragmented into varieties and sub-varieties, anarchism demanded, before anything else, harmony between deeds and words (which, in truth, is demanded by all forms of idealism, but which they all forget as they become complacent)." Serge liked to quote the words of Reclus: "As long as social injustice lasts we shall remain in a state of permanent revolution."

His biographer, Adam Hochschild, has pointed out: "He (Victor Serge) left home while still in his teens, lived in a French mining village, worked as a typesetter, and finally made his way to Paris. There he lived with beggars, read Balzac, and grew fascinated by the underworld. But soon the revolutionary in him overcame the wanderer." Serge became a follower of Albert Libertad. He later recalled in his memoirs: "No one knew his real name, or anything of him before he started preaching. Crippled in both legs, walking on crutches which he plied vigorously in fights (he was a great one for fighting, despite his handicap), he bore, on a powerful body, a bearded head whose face was finely proportioned. Destitute, having come as a tramp from the south, he began his preaching in Montmartre, among libertarian circles and the queues of poor devils waiting for their dole of soup not far from the site of Sacre Coeur. Violent, magnetically attractive, he became the heart and soul of a movement of such exceptional dynamism that it is not entirely dead even at this day. Albert Libertad loved streets, crowds, fights, ideas, and women. On two occasions he set up house with a pair of sisters, the Mahes and then the Morands. He had children whom he refused to register with the State."

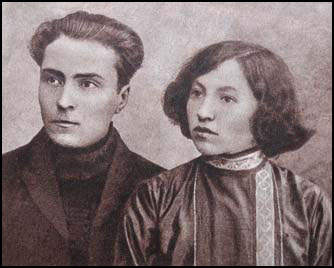

In 1909 Serge met Rirette Maitrejean in Lille. He described her as "short, slim, agressive girl, militant, with a Gothic profile". They fell in love and they lived together in Paris. Serge recalled how he worked as "a draughtsman in a machine-tool works, ten hours a day, twelve and a half including the journeys, starting at 6:30 a.m." After the death of Albert Libertad in a street-fight, the couple helped to edit l'Anarchie.

The execution of the non-violent anarchist, Francisco Ferrer in Barcelona on 13th October, 1909, had a profound impact on Serge and his friends. Serge wrote: "His transparent innocence, his educational activity, his courage as an independent thinker, and even his man-in-the-street appearance endeared him infinitely to the whole of a Europe that was, at the time, liberal by sentiment and in intense ferment. A true international consciousness was growing from year to year, step by step with the progress of capitalist civilization.... From one end of the Continent to the other (except in Russia and Turkey) the judicial murder of Ferrer had, within twenty-four hours, moved whole populations to incensed protest."

One of their friends, Liabeuf, a young worker of twenty, armed himself with a revolver and open fire on the police. He wounded four policeman and after being found guilty of attempted murder, was condemned to death. It was decided to execute him at the Boulevard Arago. Serge recalled in Memoirs of a Revolutionary (1951): "I had come with Rirette... The militants from all the groups were there, forced back by walls of black-uniformed police executing bizarre maneuvers. Shouts and angry scuffles broke out when the guillotine wagon arrived, escorted by a squad of cavalry. For some hours there was a battle on the spot, the police charges forcing us ineffectively, because of the darkness, into side streets from which sections of the crowd would disgorge once again the next minute."

Jules Bonnot

Jules Bonnot arrived in Paris in 1911. According to Serge: "From the grapevine we gathered that Bonnot... had been traveling with him by car, had killed him, the Italian having first wounded himself fumbling with a revolver." Bonnot soon formed a gang that included local anarchists, Raymond Callemin, Octave Garnier, René Valet and Edouard Carouy. Serge was totally opposed to what the group intended to do. Callemin visited Serge when he heard what he had been saying: "If you don't want to disappear, be careful about condemning us. Do whatever you like! If you get in my way I'll eliminate you!" Serge replied: "You and your friends are absolutely cracked and absolutely finished."

On 21st December, 1911 the gang robbed a messenger of the Société Générale Bank in broad daylight and then fled in a car. As Peter Sedgwick pointed out: "This was an astounding innovation when policemen were on foot or bicycle. Able to hide, thanks to the sympathies and traditional hospitality of other anarchists, they held off regiments of police, terrorized Paris, and grabbed headlines for half a year."

The police raided the offices of l'Anarchie on 31st December, 1911. Louis Jouin, the vice-chief of the French police, told him: "I know you pretty well; I should be most sorry to cause you any trouble-which could be very serious. You know these circles, these men, who are very unlike you, and would shoot you in the back, basically.... they are all absolutely finished. I can assure you. Stay here for an hour and we'll discuss them. Nobody will ever know anything of it and I guarantee that there'll be no trouble at all for you." Serge refused to help them and they arrested him along with his wife, Rirette Maitrejean. The main evidence consisted of two revolvers found on the premises of the newspaper. They were accused of being part of the Jules Bonnot gang and spent the next fifteen months in solitary confinement.

The gang murdered a police officer at the Place du Havre on 27th February, 1912. The following month, on 25th March, two more people were killed during an attack on the office of the General Corporation in Chantilly. Serge complained in Memoirs of a Revolutionary (1951): "A positive wave of violence and despair began to grow. The outlaw anarchists shot at the police and blew out their own brains. Others, overpowered before they could fire the last bullet into their own heads, went off sneering to the guillotine.... I recognized, in the various newspaper reports, faces I had met or known; I saw the whole of the movement founded by Libertad dragged into the scum of society by a kind of madness; and nobody could do anything about it, least of all myself. The theoreticians, terrified, headed for cover. It was like a collective suicide."

Raymond Callemin was arrested on 7th April, 1912, Seventeen days later, three policemen surprised Jules Bonnot in the apartment of a man known to buy stolen goods. He shot at the officers, killing Louis Jouin, the vice-chief of the French police, and wounding another officer before fleeing over the rooftops. Four days later he was discovered in a house in Choisy-le-Roi. It is claimed the building was surrounded by 500 armed police officers, soldiers and firemen. Bonnot was able to wound three officers before the house before the police used dynamite to demolish the front of the building. In the battle that followed Bonnott was shot ten times. He was moved to the Hotel-Dieu de Paris before dying the following morning. Octave Garnier and René Valet were killed during a police siege of their suburban hideout on 15th May, 1912.

The trial of Maitrejean, Serge, Raymond Callemin, Jean de Boe, Rirette Maitrejean, Edouard Carouy, André Soudy, Eugène Dieudonné and Stephen Monier, began on 3rd February, 1913. According to Serge: "In the course of a month, 300 contradictory witnesses paraded before the bar of the court. The inconsequently of human testimony is astonishing. Only one in ten can record more or less clearly what they have seen with any accuracy, observe, and remember - and then be able to recount it, resist the suggestions of the press and the temptations of his own imagination. People see what they want to see, what the press or the questioning suggest."

Callemin, Soudy, Dieudonné and Monier were sentenced to death. When he heard the judge's verdict, Callemin jumped up and shouted: "Dieudonné is innocent - it's me, me that did the shooting!" Carouy was sentenced to hard labour for life (he committed suicide a few days later). Serge received five years' solitary confinement but Maitrejean was acquitted. Dieudonné was reprieved but Callemin, Soudy and Monier were guillotined at the gates of the prison on 21st April, 1913. Maitrejean married Serge in prison in 1915 in order to have the right to visit and correspond.

First World War

Serge was in prison on the outbreak of the First World War. He immediately forecast that the war would lead to a Russian Revolution: "Revolutionaries knew quite well that the autocratic Empire, with its hangmen, its pogroms, its finery, its famines, its Siberian jails and ancient iniquity, could never survive the war." In September, 1914, Serge was in a prison on an island in the Seine, twenty-five miles or so from the Battle of the Marne. The local population, suspecting a French defeat, began to flee, and for a while Serge and the other inmates expected to become German prisoners.

On his release in 1915 he went to live in Spain. He returned to France and after the overthrow of Nicholas II in February, 1917, Serge attempted to get to Russia to join the revolution. He was arrested and imprisoned and held without trial. In October, 1918 the Danish Red Cross intervened and arranged for Serge and other revolutionaries to be exchanged for Bruce Lockhart and other anti-Bolsheviks who had been imprisoned in Russia.

Russian Revolution

When Serge arrived in Russia in 1919 he joined the Bolsheviks. For a while Serge worked for Maxim Gorky, at the Universal Literature publishing house. Soon afterwards he was employed by Gregory Zinoviev who had been appointed as President of the Executive of the Third International. Serge's knowledge of languages enabled him to organize international editions of the organization's publications. As a former anarchist, Serge had doubts about the Bolshevik government: "Even if there were only one chance in a hundred for the regeneration of the revolution and its workers' democracy, that chance had to be taken."

Serge soon became disillusioned with the Soviet government. He joined with Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman to complain about the way the Red Army treated the sailors involved in the Kronstadt Uprising. Serge's account of the rebellion was later criticised by Leon Trotsky: "Whether there were any needless victims I do not know. On this score I trust Dzerzhinsky more than his belated critics... Victor Serge's conclusions on this score - from third hand - have no value in my eyes." Serge retorted that his information on Kronstadt came from anarchist eyewitnesses he had interviewed in prison immediately after the rising: "The single fact that Trotsky did not know what all the rank-and-file Communists knew - that out of inhumanity a needless crime had been committed against the proletariat and peasantry - this fact, I repeat, is deeply significant."

A libertarian socialist, Serge protested against the Red Terror that was organized by Felix Dzerzhinsky and the Ckeka. He later recalled: "The telephone became my personal enemy. At every hour it brought me voices of panic-stricken women who spoke of arrest, imminent executions, and injustice, and begged me to intervene at once, for the love of God!"

Left Opposition

In 1923 Serge became associated with the Left Opposition group that included Leon Trotsky, Karl Radek, Adolf Joffe, Alexandra Kollontai and Alexander Shlyapnikov. Later Gregory Zinoviev and Lev Kamenev joined in the struggle against Joseph Stalin. Serge was an outspoken critic of the authoritarian way that Joseph Stalin governed the country and is believed to be the first writer to describe the Soviet government as "totalitarian".

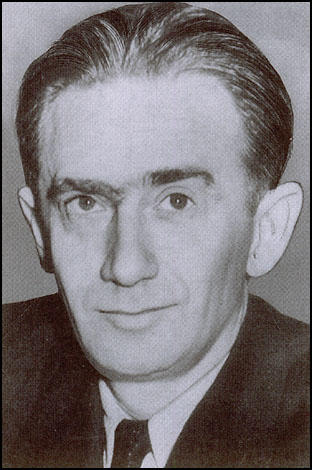

In 1928 Serge was arrested and expelled from the Communist Party. He was eventually released while suffering from severe abominable pain. Serge thought he was going to die. He told himself: "If I chance to survive, I must be quick and finish the books I have begun; I must write, write..." Serge's first book, Year One of the Russian Revolution, was finished in 1930. Adam Hochschild has pointed out: "In all his books, and particularly in this one, his masterpiece, his prose has a searing, vivid, telegraphic compactness. Serge's style comes not from endless refinement and rewriting, like Flaubert's, but from the urgency of being a man on the run. The police are at the door; his friends are being arrested; he must get the news out; every word must tell." The book was banned in the Soviet Union. So also were his novels, Men in Prison (1930) and Birth of Our Power (1931). However, they were published in France and Spain.

Serge was arrested and imprisoned in 1933. He was sent to the remote city of Orenburg, in the Ural Mountains. Most of the Left Opposition that were arrested were executed but as a result of protests made by leading politicians in France, Belgium and Spain, Serge was kept alive. The Communist Secret Police (GPU) obtained a confession from his sister-in-law, Anita Russakova, that Serge and her had been involved in a conspiracy led by Leon Trotsky. Serge knew from his contacts in the Communist Party that if he signed the confession he would be executed.

Protests against Serge's imprisonment took place at several International Conferences. The case caused the Soviet government considerable embarrassment and in 1936 Joseph Stalin announced that he was considering releasing Serge from prison. Pierre Laval, the French prime minister, refused to grant Serge an entry permit. Emile Vandervelde, the veteran socialist, and a member of the Belgian government, managed to obtain Serge a visa to live in Belgium. Serge's relatives were not so fortunate: his sister, mother-in-law, sister-in-law (Anita Russakova) and two of his brothers-in-law, died in prison.

On his arrival in France in 1936, Serge resumed work on two books on Soviet communism, From Lenin to Stalin (1937) and Destiny of a Revolution (1937). He also worked closely with a group of supporters of Leon Trotsky that included Lev Sedov, Henricus Sneevliet and Mark Zborowski. Serge also worked on the Bulletin of the Opposition, the journal "which fought against Stalinist reaction for the continuity of Marxism in the Communist International".

Walter Krivitsky

After the assassination of Ignaz Reiss, another NKVD agent, Walter Krivitsky discovered that Theodore Maly, who had refused to kill him, was recalled and executed. He now decided to defect to Canada. Once settled abroad he would collaborate with Paul Wohl on the literary projects they had so often discussed. In addition to writing about economic and historical subjects, he would be free to comment on developments in the Soviet Union. Wohl agreed to the proposal. He told Krivitsky that he was an exceptional man with rare intelligence and rare experience. He assured him that there was no doubt that together they could succeed.

Wohl agreed to help Krivitsky defect. To help him disappear he rented a villa for him in Hyères, a small town in France on the Mediterranean Sea. On 6th October, 1937, Wohl arranged for a car to collect Krivitsky, Antonina Porfirieva and their son and to take them to Dijon. From there they took a train to their new hideout on the Côte d'Azur. As soon as he discovered that Krivitsky had fled, Mikhail Shpiegelglass told Nikolai Yezhov what had happened. After he received the report, Yezhov sent back the command to assassinate Krivitsky and his family.

Later that month Walter Krivitsky wrote to Elsa Poretsky and told her what he had done and to express concerns that the NKVD had a spy close to her friend, Henricus Sneevliet. "Dear Elsa, I have broken with the Firm and am here with my family. After a while I will find the way to you, but right now I beg you not to tell anyone, not even your closest friends, who this letter is from... Listen well, Elsa, your life and that of your child are in danger. You must be very careful. Tell Sneevliet that in his immediate vicinity informers are at work, apparently also in Paris among the people with whom he has to deal. He should be very attentive to your and your child's welfare. We both are completely with you in your grief and embrace you." He gave the letter to Gerard Rosenthal, who took it to Sneevliet who passed it onto Poretsky.

Krivitsky also arranged a meeting with Hans Brusse who he hoped to persuade him to defect. Brusse refused declaring that he had come to the meeting "in the name of the organization". He then pulled out a copy of Krivitsky's letter to Elsa. Krivitsky was deeply shocked, but denied having written the letter. He suspected that he knew he was lying. Brusse pleaded with Krivitsky to return to his work as a Soviet spy.

On 11th November, 1937, Walter Krivitsky had a meeting with Elsa Poretsky, Henricus Sneevliet, Pierre Naville and Gerard Rosenthal. Poretsky later recalled in Our Own People (1969) that Krivitsky said to her: "I come to warn you that you and your child are in grave danger. I came in the hope that I could be of some help." She replied: "Your warning comes too late. Had you done this in time Ignaz would be alive now, here with us... If you had joined him, as you said you would and as he expected, he would be alive and you would be in a different position." Krivitsky, visibly shocked by her response, said: "Of all that has happened to me this is the hardest blow."

Krivitsky then told the group that Brusse had showed him the letter that he had sent to Poretsky. He asked Rosenthal if he had showed the letter to anyone before giving it to Sneevliet. He admitted that he had asked Victor Serge to post the letter. He later admitted to Sneevliet that he had also shown it to Mark Zborowski. Krivitsky knew that one of these people had given a copy of the letter to Brusse, who had remained loyal to the NKVD.

Krivitsky believed the spy was either Serge or Zborowski. On 20th November, 1937, Krivitsky arranged to meet Serge on the Square Port-Royal. Serge later recalled in his book, Memoirs of a Revolutionary (1951) that Krivitsky was a "thin little man with premature wrinkles and nervous eyes". According to Serge, Krivitsky told him that he remained loyal to the Soviet Union, since "the historic mission of this state was far more important than its crimes, and besides he himself did not believe that any opposition could succeed".

Serge commented that "Krivitsky was afraid of lighted streets. Each time that he put his hand into his overcoat pocket to reach for a cigarette, I followed his movements very attentively and put my own hand in my pocket." Krivitsky told Serge: "I am risking assassination at any moment and you still don't trust me, do you?" Serge admitted that was true. "And we would both agree to die for the same cause: isn't that so?" Serge replied: "Perhaps, all the same it would be as well to define just what this cause is."

Mexico City

When France was invaded by Germany in 1940, Serge managed to escape to Mexico where he continued to write. According to his biographer, Peter Sedgwick: "All these millions of words were typed by Serge in cramped single-spacing on reams of the cheapest flimsy, with rarely an erasure or amendment. When one manuscript was finished he went straight on to the next without looking back." His friend, Julián Gorkin, reading through his memoirs, commented that his material was so rich that it should be developed and expanded. Serge replied: "What would be the use? Who would publish me? And besides. I am pressed for time. Other books are waiting."

Victor Serge's health had been badly damaged by his periods of imprisonment in France and Russia. However, he continued to write until dying of a heart-attack in Mexico City on 17th November, 1947. He died penniless, and his friends had to make a collection among themselves to pay the expenses of his burial. It was several years later before his autobiography, Memoirs of a Revolutionary, and his last two novels, The Long Dusk and The Case of Comrade Tulayev, were published in the United States.

Primary Sources

(1) In 1910 several of Victor Serge's anarchist friends in Paris were arrested and executed for acts of terrorism. This included Andre Soudy, a man he wrote about in his book Memoirs of a Revolutionary (1951).

I had often met Soudy at public meetings in the Latin Quarter. He was the perfect example of the crushed childhood of the back-alleys. He grew up on the pavements: T.B. at thirteen, V.D. at eighteen, convicted at twenty (for stealing a bicycle). I had brought him books and oranges in the Tenon Hospital. Pale, sharp-featured, his accent common, his eyes a gentle grey, he would say, "I'm an unlucky blighter, nothing I can do about it."

He earned his living in grocers' shops in the Rue Mouffetard, where the assistants rose at six, arranged the display at seven, and went upstairs to sleep in a garret after 9 p.m., dog-tired, having seen their bosses defrauding housewives all day by weighing the beans short, watering the milk, wine and paraffin, and falsifying the labels.

He was sentimental; the laments of street-singers moved him to the verge of tears, he could not approach a woman without making a fool of himself, and half a day in the open air of the meadows gave him a lasting dose of intoxication. He experienced a new lease of life if he hears someone call him "comrade" or explain that one could, one must, "become a new man".

Soudy's last-minute request was for a cup of coffee with cream and some fancy rolls, his last pleasure on earth, appropriate enough for that grey morning when people were happily eating their breakfast in the last bistros. It must have been too early, for they could only find him a little black coffee. "Out of luck", he remarked, "right to the end."

He was fainting with fright and nerves, and had to be supported while he was going down the stairs; but he controlled himself and, when he saw the clearness of the sky over the chestnut trees, hummed a sentimental street-song: "Hail, O last morning of mine".

(2) Victor Serge was in prison in France when he heard that the First World War had begun. He immediately predicted that the war would result in a Russian Revolution.

The outbreak of war was sudden, like an unexpected storm in a season of clear weather. For me, it heralded another, purifying tempest: the Russian Revolution. Revolutionaries knew quite well that the autocratic Empire, with its hangmen, its pogroms, its finery, its famines, its Siberian jails and ancient iniquity, could never survive the war.

(3) Victor Serge met Lilina Zinoviev soon after arriving in Russia.

Zinoviev's wife Lilina, People's Commissar for Social Planning in the Northern Commune, a small crop-haired, grey-eyed woman in a uniform jacket, sprightly and tough, asked me, "Have you brought your families with you? I could put them up in palaces, which I know is very nice on some occasions, but it is impossible to heat them. You'd better go to Moscow. Here, we are besieged people in a besieged city. Hunger-riots may start, the Finns may swoop on us, the British may attack. Typhus has killed so many people that we can't manage to bury them; luckily they are frozen. If work is what you want, there's plenty of it!" And she told me passionately of the Soviet achievement: school-building, children centres, relief for pensioners, free medical assistance, the theatres open to all.

(4) Victor Serge wrote about the Mensheviks in his autobiography, Memoirs of a Revolutionary (1951)

I met the Menshevik leaders, and certain anarchists. Both sets denounced Bolshevik intolerance, the stubborn refusal to revolutionary dissenters of any right to exist, and the excesses of the Terror. The Mensheviks seemed to me to be admirably intelligent, honest and devoted to Socialism, but completely overtaken by events. They stood for a sound principle, that of working-class democracy, but in a situation fraught with such mortal danger that the stage of siege did not permit any functioning of democratic institutions.

(5) Victor Serge, Year One of the Russian Revolution (1930)

An Anarchist schoolmaster and former political prisoner, named Nestor Makhno, opened up guerrilla warfare at Gulai-Polye, with fifteen men at his side; these attacked German sentries to obtain weapons. Later on, Makhno was to form whole armies. The Germans repressed these movements with the utmost vigour, executing prisoners en masse and burning down villages; but it was all too much for them.

(6) Victor Serge, Memoirs of a Revolutionary (1945)

Since the first massacres of Red prisoners by the Whites, the murders of Volodarsky and Uritsky and the attempt against Lenin (in the summer of 1918), the custom of arresting and, often, executing hostages had become generalized and legal. Already Cheka, which made mass arrests of suspects, the was tending to settle their fate independently, under formal control of the Party, but in reality without anybody's knowledge.

The Party endeavoured to head it with incorruptible men like the former convict Dzerzhinsky, a sincere idealist, ruthless but chivalrous, with the emaciated profile of an Inquisitor: tall forehead, bony nose, untidy goatee, and an expression of weariness and austerity. But the Party had few men of this stamp and many Chekas.

I believe that the formation of the Chekas was one of the gravest and most impermissible errors that the Bolshevik leaders committed in 1918 when plots, blockades, and interventions made them lose their heads. All evidence indicates that revolutionary tribunals, functioning in the light of day and admitting the right of defence, would have attained the same efficiency with far less abuse and depravity. Was it necessary to revert to the procedures of the Inquisition?

By the beginning of 1919, the Chekas had little or no resistance against this psychological perversion and corruption. I know for a fact that Dzerzhinsky judged them to be "half-rotten", and saw no solution to the evil except in shooting the worst Chekists and abolishing the death-penalty as quickly as possible.

(7) The winter of 1920 brought severe food and fuel shortages. Serge wrote about the situation in his book Memoirs of a Revolutionary.

The winter of 1920 was a torture (there is no other word for it) for the towns people: no heating, no lighting, and the ravages of famine. Children and feeble old folk died in their thousands. Typhus was carried everywhere by lice, and took its frightful toll. Inside Petrograd's grand apartments, now abandoned, people were crowded in one room, living on top of one another around a little stove of brick or cast-iron which would be standing on the floor, its flue belching smoke through an opening in the window. Fuel for it would come from the floor-boards of rooms near by, from the last stick of furniture available, or else from books. Entire libraries disappeared in this way.

(8) Victor Serge, along with Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman, had attempted to mediate between the Kronstadt sailors and the Soviet government. His account of the uprising appeared in his book Memoirs of a Revolutionary.

The final assault was unleashed by Tukhacevsky on 17 March, and culminated in a daring victory over the impediment of the ice. Lacking any qualified officers, the Kronstadt sailors did not know how to employ their artillery; there was, it is true, a former officer named Kozlovsky among them, but he did little and exercised no authority. Some of the rebels managed to reach Finland. Others put up a furious resistance, fort to fort and street to street; they stood and were shot crying, "Long live the world revolution! Hundreds of prisoners were taken away to Petrograd and handed to the Cheka; months later they were still being shot in small batches, a senseless and criminal agony. Those defeated sailors belonged body and soul to the Revolution; they had voiced the suffering and the will of the Russian people. This protracted massacre was either supervised or permitted by Dzerzhinsky.

(9) Victor Serge, Memoirs of a Revolutionary (1951)

The Workers Opposition, led by Shliapnikov, Alexandra Kollontai, and Medvedev, believed that the revolution was doomed if the Party failed to introduce radical changes in the organization of work, restore freedom and authority to the trade unions, and make an immediate turn towards establishing a true Soviet democracy. I had long discussions on this question with Shliapnikov. A former metalworker, he kept about him, even when in power, the mentality, the prejudices, and even the old clothes he had possessed as a worker. He distrusted the officials ("that multitude of scavengers") and was sceptical about the Comintern, seeing too many parasites in it who were only hungry for money.

(10) Victor Serge, Memoirs of a Revolutionary (1951)

Maxim Gorky welcomed me affectionately. In the famished years of his youth, he had been acquainted with my mother's family at Nizhni-Novgorof. His apartment at the Kronversky Prospect, full of books, seemed as warm as a greenhouse. He himself was chilly even under his thick grey sweater, and coughed terribly, the result of his thirty years' struggle against tuberculosis. Tall, lean and bony, broad-shouldered and hollow-chested, he stooped a little as he walked. His frame, sturdily-built but anaemic, appeared essentially as a support for his head. An ordinary, Russian man in the street's head, bony and pitted, really almost ugly with its jutting cheek-bones, great thin-lipped mouth and professional smeller's nose, broad and peaked.

He spoke harshly about the Bolsheviks: they were "drunk with authority", "cramping the violent, spontaneous anarchy of the Russian people", and "starting bloody despotism all over again"; all the same they were "facing chaos alone" with some incorruptible men in their leadership. His observations always started from facts, from chilling anecdotes upon which he would base his well-considered generalizations.

(11) In 1933 Victor Serge was taken to the headquarters of the Communist Secret Police (GPU).

It was a prison of noiseless, cell-divided secrecy, built barely into a block that had once been occupied by insurance company offices. Each floor formed a prison on its own, sealed off from the others, with its individual entrance and reception-kiosk; coloured electric light-signals operated on all landings and corridors to mark the various comings and goings, so that prisoners could never meet one another. A mysterious hotel-corridor, whose red carpet silenced the slight sound of footsteps; and then a cell, bare, with an inlaid floor, a passable bed, a table and a chair, all spick and span.

Here, in absolute secrecy, with no communication with any person whatsoever, with no reading-matter whatsoever, with no paper, not even one sheet, with no occupation of any kind, with no open-air exercise in the yard, I spent about eighty days. It was a severe test for the nerves, in which I acquitted myself pretty well. I was weary with my years of nervous tension, and felt an immense physical need for rest. I slept as much as I could, at least twelve hours a day. The rest of the time, I set myself to work assiduously. I gave myself courses in history, political economy - and even in natural science! I mentally wrote a play, short stories, poems.

(12) Rutkovsky was one of the members of the Communist Secret Police (GPU) who interviewed Victor Serge in 1933. He attempted to get Serge to sign a confession agreeing that he had worked with Anita Russakova against the Soviet government. Serge knew that once he signed a confession he would be executed.

I can see that you are an unwavering enemy. You are bent on destroying yourself. Years of jail are in store for you. You are the ringleader of the Trotskyite conspiracy. We know everything. I want to try and save you in spite of yourself. This is the last time that we try. So, I'm making one last attempt to save you.

I don't expect very much from you - I know you too well. I am going to acquaint you with the complete confessions that have been made by your sister-in-law and secretary, Anita Russakova. All you have to do it say, "I admit that it is true", and sign it. I won't ask you any more questions, the investigation will be closed, your whole position will be improved, and I shall make every effort to get the Collegium to be lenient to you.

(13) Victor Serge, Memoirs of a Revolutionary (1951)

And on 14 August, like a thunderbolt, came the announcement of the Trial of the Sixteen, concluded on the 25th - eleven days later - by the execution of Zinoviev, Kamenev, Ivan Smirnov, and all their fellow-defendants. I understood, and wrote at once, that this marked the beginning of the extermination of all the old revolutionary generation. It was impossible to murder only some, and allow the others to live, their brothers, impotent witnesses maybe, but witnesses who understood what was going on.

(14) Victor Serge, Destiny of a Revolution (1937)

The bureaucracy itself could, it seems, have a less disastrous policy without difficulty, if it had displayed more general culture and Socialist spirit. Its infatuation with administrative and military methods, joined to a penchant for panic in critical moments, reduced its real means. In despotic regimes, too many things depend on the tyrant.

(15) Victor Serge, Memoirs of a Revolutionary (1951)

The young French and Belgian rebels of my twenties have all perished; my syndicalist comrades of Barcelona in 1917 were nearly all massacred; my comrades and friends of the Russian Revolution are probably all dead - any exceptions are only by a miracle. All were brave, all sought a principle of life nobler and juster than that of surrender to the bourgeois order; except perhaps for certain young men, disillusioned and crushed before their consciousness had crystallized, all were engaged in movements for progress. I must confess that the feeling of having so many dead men at my back, many of them my betters in energy, talent, and historical character, has often overwhelmed me.