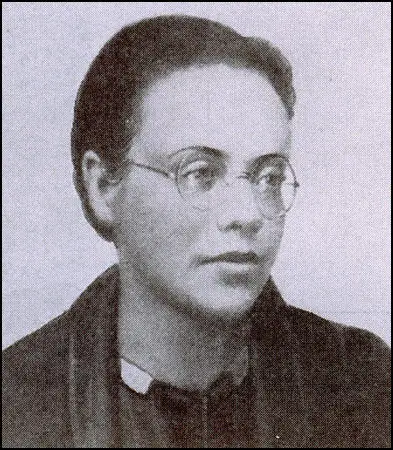

Elsa Poretsky

Elsa Bernaut met Ignace Poretsky in Moscow in 1921. Using the name Ignaz Reiss he was working as a spy for Felix Dzerzhinsky, the head of the All-Russian Extraordinary Commission for Combating Counter-Revolution and Sabotage (Cheka). They married and returned to Poland with her husband. In 1922 he was arrested and charged with espionage. Facing a five-year sentence he managed to escape on the way to prison.

Ignaz Reiss, accompanied by his wife, Elsa Poretsky, was now sent to work in Berlin. During this period he became friends with Karl Radek, Angelica Balabanoff, Theodore Maly, Richard Sorge and Hans Brusse. In 1927, he returned briefly to the Soviet Union, where he received the Order of the Red Banner. Reiss spent time in Vienna before obtaining a post in Moscow, where he joined the Polish section of the Comintern.

Paris and Berlin

In 1932 Reiss became a NKVD official in Paris. He was therefore out of the country when Gregory Zinoviev, Lev Kamenev and fourteen other defendants had been executed after they were found guilty of trying to overthrow Joseph Stalin. This was the first of the Show Trials and the beginning of the Great Purge. According to Gary Kern, the author of A Death in Washington: Walter G. Krivitsky and the Stalin Terror (2004): "The Zinoviev-Kamenev trial of August 1936 defamed Lenin's confederates, in a sense the founding fathers of that state. When he learned of the trial's monstrous conclusion, the death penalty for all sixteen defendants, he felt he could no longer belong."

Ignaz Reiss met his old friend, Walter Krivitsky, who was also working for the Russian Secret Police, and suggested that they should both defect in protest as a united demonstration against the purge of leading Bolsheviks. Krivitsky rejected the idea. He suggested that the Spanish Civil War, which had just begun, would probably revive the old revolutionary spirit, empower the Comintern and ultimately drive Stalin from power. Krivitsky also made the point that that there was no one to whom they could turn. Going over to Western intelligence services would betray their ideals, while approaching Leon Trotsky and his group would only confirm Soviet propaganda, and besides, the Trotskists would probably not trust them.

Elsa Poretsky visited Moscow in early 1937. She noted that: "The Soviet citizen does not rejoice in the splendor, he does not marvel at the blood trials, he hunches down deeper, hoping only perhaps to escape ruin. Before every Party member the dread of the purge. Over every Party member and non-Party member the lash of Stalin. Lack of initiative it's called, then lack of vigilance - counter-revolution, sabotage, Trotskyism. Terrified to death, the Soviet man hastens to sign resolutions. He swallows everything, says yea to everything. He has become a clod. He knows no sympathy, no solidarity. He knows only fear."

NKVD Purge

In December 1936, Nikolai Yezhov established a new section of the NKVD named the Administration of Special Tasks (AST). It contained about 300 of his own trusted men from the Central Committee of the Communist Party. Yezhov's intention was complete control of the NKVD by using men who could be expected to carry out sensitive assignments without any reservations. The new AST operatives would have no allegiance to any members of the old NKVD and would therefore have no reason not to carry out an assignment against any of one of them. The AST was used to remove all those who had knowledge of the conspiracy to destroy Stalin's rivals. One of the first to be arrested was Genrikh Yagoda, the former head of the NKVD.

Within the administration of the ADT, a clandestine unit called the Mobile Groups had been created to deal with the ever increasing problem of possible NKVD defectors, as officers serving abroad were beginning to see that the arrest of people like Yagoda, their former chief, would mean that they might be next in line. By the summer of 1937, an alarming number of intelligence agents serving abroad were summoned back to the Soviet Union. Rumours began to spread that these men were being executed.

Richard Deacon, the author of A History of the Russian Secret Service (1972) has pointed out: "Ignace Reiss suddenly realised that before long he, too, might well be next on the list for liquidation. He had been loyal to the Soviet Union, he had carried out all tasks assigned to him with efficiency and devotion, but, though not a Trotskyite, he was the friend of Trotskyites and opposed to the anti-Trotsky campaign. One by one he saw his friends compromised on some trumped-up charge, arrested and then either executed or allowed to disappear for ever. When Reiss returned to Europe he must already have known that he had little choice in future: either he must defect to safety, or he must carry on working until he himself was liquidated."

Walter Krivitsky was also recalled to Moscow. He later claimed that he took the opportunity to "find out at firsthand what was going on in the Soviet Union". Krivitsky wrote that Joseph Stalin had lost the support of most of the Soviet Union: "Not only the immense mass of the peasants, but the majority of the army, including its best generals, a majority of the commissars, 90 percent of the directors of factories, 90 percent of the Party machine, were in more or less extreme degree opposed to Stalin's dictatorship."

Krivitsky met up with Ignaz Reiss in Rotterdam on 29th May, 1937. He told Reiss that Moscow was a "madhouse" and that Nikolai Yezhov was "insane". Krivitsky agreed with Reiss that the Soviet Union had "devolved into a Fascist state" but refused to defect. Krivitsky later explained: "The Soviet Union is still the sole hope of the workers of the world. Stalin may be wrong. Stalins will come and go, but the Soviet Union will remain. It is our duty to stick to our post." Reiss disagreed with Krivitsky and said if that was his view he would go it alone. Elsa Poretsky also began to doubt the loyalty of Krivitsky. She began to wonder why he had been allowed to leave Moscow. She told her husband: "No one leaves the Soviet Union unless the NKVD can use him."

In July 1937 Ignaz Reiss received a letter from Abram Slutsky and was warned that if he did not go back to Moscow at once he would be "treated as a traitor and punished accordingly". It was therefore decided to defect. Elsa rented a house in Finhaut, a picturesque village in southern Switzerland, just over the border from France and Ignaz took a room in a Paris hotel.

Reiss also received a letter from Gertrude Schildbach. At the time she was living in Rome and she asked if she could see Reiss. He agreed and then went to a meeting with Henricus Sneevliet in Amsterdam. Sneevliet later told Victor Serge and his fellow Trotskyists that "Ignace Reiss was warning us that we were all in peril, and asking to see us. Reiss was at present hiding in Switzerland. We arranged to meet him in Rheims on 5 September 1937."

Letter to Stalin

Reiss wrote a series of letters that he gave in to the Soviet Embassy in Paris explaining his decision to break with the Soviet Union because he no longer supported the views of Stalin's counter-revolution and wanted to return to the freedom and teachings of Lenin. "Up to this moment I marched alongside you. Now I will not take another step. Our paths diverge! He who now keeps quiet becomes Stalin's accomplice, betrays the working class, betrays socialism. I have been fighting for socialism since my twentieth year. Now on the threshold of my fortieth I do not want to live off the favours of a Yezhov. I have sixteen years of illegal work behind me. That is not little, but I have enough strength left to begin everything all over again to save socialism. ... No, I cannot stand it any longer. I take my freedom of action. I return to Lenin, to his doctrine, to his acts." These letters were addressed to Joseph Stalin and Abram Slutsky.

Mikhail Shpiegelglass told Walter Krivitsky that Reiss had gone over to the Trotskyists and described him meeting Henricus Sneevliet in Amsterdam. Krivitsky assumed from this information that Stalin had a spy within Sneevliet's group. Krivitsky correctly guessed that this was Mark Zborowski. Krivitsky and another NKVD agent, Theodore Maly, tried to contact Reiss. Recently released NKVD files show that Shpiegelglass ordered Maly to take an iron and beat Reiss to death in his hotel room. Maly refused to carry out this order and criticised Shpiegelglass in his report to Moscow.

Ignaz Reiss now joined Elsa Poretsky in Finhaut. According to Elsa his hair had turned white during the ten days he had been hiding in France. After several days he showed his wife a copy of the letter he had sent to Stalin. She now realized that "our world was gone forever, we had no past, we had no future, there was only the present." They had no income and nowhere to go. They also had no legal status anywhere.

Death of Ignaz Reiss

Reiss wrote to Henricus Sneevliet and suggested a meeting in Reims on 5th September. He also contacted Gertrude Schildbach and arranged to see her at a cafe in Lausanne. According to Gary Kern, the author of A Death in Washington: Walter G. Krivitsky and the Stalin Terror (2004): "They found Schildbach unusually well dressed and full of stories about a rich industrialist she was going to marry, stories which they took with a dash of salt. They sat by a window, Elsa beside her and Ignace across, as she chattered nervously about her urgent matter - her desire to defect. Ignace advised her to get in touch with the Trotskyists."

Elsa returned to their home in Finhaut and Reiss planned to take the train to Reims to meet Sneevliet. Victor Serge later wrote: "We arranged to meet him in Reims on 5 September 1937. We waited for him at the station buffet, then at the post office. He did not appear. Puzzled, we wandered through the town, admiring the cathedral... drinking champagne in small cafes, and exchanging the confidences of men who have been saddened through a surfeit of bitter experiences."

Ignaz Reiss and Gertrude Schildbach went for supper outside of town. They left the restaurant and set off on foot. A car pulled up bearing two NKVD agents, Francois Rossi and Etienne Martignat. One was driving, the other - holding a machine-gun. Reiss was shot seven times in the head and five times in the body. The assassins fled, not bothering to check out of the hotel in Lausanne. They abandoned the car in Berne. The police found a box of chocolates, laced with strychnine, in the hotel room. It is believed these were intended for Elsa and her son Roman.

Walter Krivitsky

Abram Slutsky now grew very suspicious of Krivitsky and insisted that he turned over his spy-ring to Mikhail Shpiegelglass. This included his second in command, Hans Brusse. Soon afterwards, Brusse made contact with Krivitsky and told him that Shpiegelglass had ordered him to kill Elsa Poretsky and her son. Krivitsky advised him to accept the mission, but to sabotage the operation. Krivitsky also suggested that Brusse should gradually withdraw from working for the NKVD. According to Krivitsky's account in I Was Stalin's Agent (1939), Brusse agreed to this strategy.

After the assassination of Ignaz Reiss, Krivitsky discovered that Theodore Maly, who had refused to kill him, was recalled and executed. He now decided to defect to Canada. Once settled abroad he would collaborate with Paul Wohl on the literary projects they had so often discussed. In addition to writing about economic and historical subjects, he would be free to comment on developments in the Soviet Union. Wohl agreed to the proposal. He told Krivitsky that he was an exceptional man with rare intelligence and rare experience. He assured him that there was no doubt that together they could succeed.

Wohl agreed to help Krivitsky defect. To help him disappear he rented a villa for him in Hyères, a small town in France on the Mediterranean Sea. On 6th October, 1937, Wohl arranged for a car to collect Krivitsky, Antonina Porfirieva and their son and to take them to Dijon. From there they took a train to their new hideout on the Côte d'Azur. As soon as he discovered that Krivitsky had fled, Mikhail Shpiegelglass told Nikolai Yezhov what had happened. After he received the report, Yezhov sent back the command to assassinate Krivitsky and his family.

Later that month Krivitsky wrote to Elsa Poretsky and told her what he had done and to express concerns that the NKVD had a spy close to her friend, Henricus Sneevliet. "Dear Elsa, I have broken with the Firm and am here with my family. After a while I will find the way to you, but right now I beg you not to tell anyone, not even your closest friends, who this letter is from... Listen well, Elsa, your life and that of your child are in danger. You must be very careful. Tell Sneevliet that in his immediate vicinity informers are at work, apparently also in Paris among the people with whom he has to deal. He should be very attentive to your and your child's welfare. We both are completely with you in your grief and embrace you." He gave the letter to Gerard Rosenthal, who took it to Sneevliet who passed it onto Poretsky.

On 7th November, 1937, Krivitsky returned to Paris where Paul Wohl arranged for him to meet Lev Sedov, the son of Leon Trotsky, and the leader of the Left Opposition in France an editor of the Bulletin of the Opposition. Sedov put him in touch with Fedor Dan, who had a good relationship with Leon Blum, the leader of the French Socialist Party and a member of the Popular Front government. Although it took several weeks, Krivitsky received French papers and if needed, a police guard.

Krivitsky also arranged a meeting with Hans Brusse who he hoped to persuade him to defect. Brusse refused declaring that he had come to the meeting "in the name of the organization". He then pulled out a copy of Krivitsky's letter to Elsa. Krivitsky was deeply shocked, but denied having written the letter. He suspected that he knew he was lying. Brusse pleaded with Krivitsky to return to his work as a Soviet spy.

On 11th November, 1937, Krivitsky had a meeting with Elsa Poretsky, Henricus Sneevliet, Pierre Naville and Gerard Rosenthal. Poretsky later recalled in Our Own People (1969) that Krivitsky said to her: "I come to warn you that you and your child are in grave danger. I came in the hope that I could be of some help." She replied: "Your warning comes too late. Had you done this in time Ignaz would be alive now, here with us... If you had joined him, as you said you would and as he expected, he would be alive and you would be in a different position." Krivitsky, visibly shocked by her response, said: "Of all that has happened to me this is the hardest blow."

Krivitsky then told the group that Brusse had showed him the letter that he had sent to Poretsky. He asked Rosenthal if he had showed the letter to anyone before giving it to Sneevliet. He admitted that he had asked Victor Serge to post the letter. He later admitted to Sneevliet that he had also shown it to Mark Zborowski. Krivitsky knew that one of these people had given a copy of the letter to Brusse, who had remained loyal to the NKVD.

Investigation

Boris Nicolaevsky decided to carry out an investigation to discover who the traitor was in the group. He approached another defector, Walter Krivitsky, and asked him for his views. Krivitsky suggested that Victor Serge was the traitor. We now know it was Mark Zborowski. As Gary Kern, the author of A Death in Washington: Walter G. Krivitsky and the Stalin Terror (2004), has pointed out: "Not satisfied with Krivitsky's abstract logic, Nicolaevsky pressed him to make a more specific report in short, to name his chief suspect. Krivitsky obliged in October 1938 with a personal letter to Nicolaevsky, again writing with painful deliberation and pedantic punctiliousness, but giving weighty reasons for suspecting Victor Serge. The verdict seems wrongheaded and even ironic today, in the light of what is known about Mark Zborowski, yet history has not completely cleared Serge of suspicion, despite apologies in the literature about his political lightheadedness and naive artist's indiscretion. Krivitsky points out that there was no other case in Soviet history of a man first arrested and imprisoned as a Trotskyist, then given not only his freedom, but also permission to travel abroad, all this at a time when other accused Trotskyists were suffering monstrous persecutions."

Life in the United States

Elsa arrived in America on 11th February, 1941. She reverted to her maiden name of Bernaut and got a job at Columbia University. Her true identity was discovered in 1948 and she was interviewed by the FBI. Mark Zborowski the NKVD agent who she believed was involved in her husband's death, also arrived in the United States that year. He immediately made contact with David Dallin and his wife Lilia Estrin. They helped him find employment at a factory in Brooklyn and set him up in an apartment. A few months later he moved to a more expensive home at 201 West 108th Street, where the Dallins also lived. It was later discovered that the NKVD were paying Zborowski to spy on the Dallins. In 1944 he helped with the search for Victor Kravchenko who had defected to the United States.

The former NKVD agent, Alexander Orlov, appeared before the Senate Internal Security Subcommittee in September 1955. He disclosed that Mark Zborowski had been involved in the killing of Ignaz Reiss and Lev Sedov. Zborowski appeared before the committee in February 1956. He admitted to being a Soviet agent working against the supporters of Leon Trotsky in Europe in the 1930s but denied that he had continued these activities in the United States. Other evidence suggested he was lying and in November 1962, he was convicted of perjury and received a four-year prison sentence.

Elsa Poretsky, the widow of Ignaz Reiss, had a meeting with Zborowski soon after he was released from prison. She asked him if he had leaked the letter from Walter Krivitsky that enabled the NKVD to find out where her husband was hiding in Switzerland and killing him. Elsa later told a friend: "A wry, pitiful smile on his distorted face and a shrug of the shoulders were his only reply." She published a book on her husband, Our Own People, in 1969.

Elsa Poretsky died in 1978.

Primary Sources

(1) Elsa Poretsky, Our Own People (1969)

Victor Serge’s natural curiosity had made him keep seeing all kinds of people, Party members, ex-Party members, former anarchists, every kind of oppositionist, until the day he was arrested in Leningrad in 1933. Some considered this showed courage, others irresponsibility. It was probably a bit of both, but carrying on as he did exposed others as well as himself to danger. More baffling still was the fact that Serge had managed to come out of the Soviet Union in 1936. We continued to have doubts about him.