Christine Keeler

Christine Keeler was born in Uxbridge on 22nd February, 1942. Her father deserted the family during the Second World War. Her mother, Julie Payne, later lived with Edward Huish and the couple set-up home in a converted railway carriage in Wraysbury. Christine later recalled: "The railway carriage was on wheels and I felt like a character from the American television series about the legendary Wild West train-driver Casey Jones."

Keeler left school without qualifications: "At fifteen, on my birthday, Mum took me to the employment agency and they found me an office typing job. After that, I had another five jobs, one after the other, and I hated them all."

In 1958 she found work as a model in a showroom in London. An affair with a local boy, Jeff Perry, resulted in her getting pregnant. The child was born prematurely and survived just six days. "I was just seventeen, I did not have many illusions left and the ones that did remain were soon to vanish... After the abortion, I began my search for a guardian angel - someone to love and someone to guide me."

Keeler found work as a waitress at a restaurant on Baker Street before finding employment as a showgirl at Murray’s Cabaret Club in Soho. "There was a pervasive atmosphere of sex, with beautiful young girls all over the place, but customers would always say, if asked, that they only came for the floor show and the food and drink... When we weren't onstage, we were allowed to sit out with the audience for a hostess fee of five pounds. That way I was soon making about thirty pounds a week."

Soon after starting this new job at Murray’s Cabaret Club she met Stephen Ward. It was not long before she decided to go and live with him at his flat in Orme Court in Bayswater. "His flat was tiny and on the top floor but there was a lift. There was a bed-sitting room with two single beds pushed close together, and an adjoining bathroom. we would share the bed but only as brother and sister; there were never to be any sexual goings-on between us."

Stephen Ward was an osteopath and one of his patients was Lord Astor. He allowed him the use of a cottage on his Cliveden Estate. War also introduced Keeler to his friends. This included Peter Rachman, the famous slum landlord and the actor, Douglas Fairbanks Jr. Ward's patients included Colin Coote, the editor of the Daily Telegraph, Roger Hollis, the head of MI5, Anthony Blunt, Surveyor of the Queen's Pictures and Geoffrey Nicholson, the Conservative MP.

Ward was also an artist and he had a reputation for producing fine portraits of his friends. This included the Duke of Edinburgh. Afterwards he told Keeler: "Philip's a snob, not like the man he used to be - I used to know him before he was married to Elizabeth". He also sketched Madame Furtseva, the Soviet Minister of Culture. Colin Coote arranged for the drawing to appear in the Daily Telegraph.

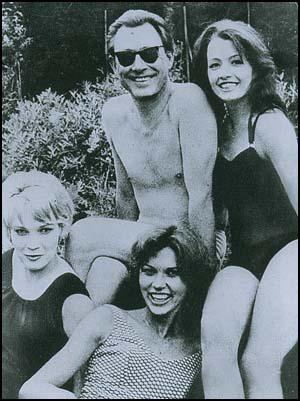

During this period Keeler also got to know Mandy Rice-Davies, Suzy Chang and Maria Novotny, who ran sex parties in London. So many senior politicians attended that she began referring to herself as the "government's Chief Whip". As well as British politicians such as John Profumo and Ernest Marples, foreign leaders such as Willy Brandt and Ayub Khan, attended these parties.

On 21st January 1961, Colin Coote invited Stephen Ward to have lunch with Eugene Ivanov, an naval attaché at the Soviet embassy. The following month Ward and Keeler moved to 17 Wimpole Mews in Marylebone. According to Keeler's autobiography, The Truth at Last (2001), Roger Hollis and Anthony Blunt were regular visitors to the flat. "He (Lord Denning) knew that Stephen was a spy and that I knew too much. During my two sessions with him I told him all about Hollis and Blunt: how Stephen had politely introduced me and how I had said 'hello' and nodded when they visited. I told him all about Sir Godfrey's visit and how I had seen Sir Godfrey with Eugene. He asked me very precisely who had met Eugene and about the visitors to Wimpole Mews. He showed me a photograph of Hollis - it wasn't a sharp shot of him - and asked me to identify him. I told Denning this was the man who had visited Stephen. He showed me a photograph of Sir Godfrey and I also identified him. He did not show me a picture of Blunt for, I suspect, they already knew more than they wanted to know about Blunt. Denning was very gentle about it and I told him everything. This was the nice gentleman who was going to look after me. But I was ignored, side-lined - disparaged as a liar so that he could claim that there had been no security risk. It was the ultimate whitewash."

Stephen Ward also got to know Keith Wagstaffe of MI5. On 8th June 1961, the two men went out to dinner before going back to the Wimpole Mews flat. Keeler made the two men coffee: "Stephen was on the couch and Wagstaffe sat on the sofa chair. He wanted to know about Stephen's friendship with Eugene. We knew that MI5 were monitoring embassy personnel so this was quite a normal interview in the circumstances." Wagstaffe asked Ward: "He's never asked you to put him in touch with anyone you know? Or for information of any kind." Ward replied: "No, he hasn't. But if he did, naturally I would get in touch with you straight away. If there's anything I can do I'd be only too pleased to."

Keith Wagstaffe reported back to MI5: "Ward asked me if it was all right for him to continue to see Ivanov. I replied that there was no reason why he should not. He then said if there was any way in which he could help he would be very ready to do so. I thanked him for his offer and asked him to get in touch with me should Ivanov at any time in the future make any propositions to him... Ward was completely open about his association with Ivanov... I do not think that he (Ward) is of security interest."

On 8th July 1961 Keeler met John Profumo, the Minister of War, at a party at Cliveden. Profumo kept in contact with Keeler and they eventually began an affair. At the same time Keeler was sleeping with Eugene Ivanov, a Soviet spy. According to Keeler: "Their (Ward and Hollis) plan was simple. I was to find out, through pillow talk, from Jack Profumo when nuclear warheads were being moved to Germany."

Keeler was also invited to sex parties. In December 1961 Mariella Novotny held a party that became known as the "Feast of Peacocks". According to Christine Keeler, there was "a lavish dinner in which this man wearing only... a black mask with slits for eyes and laces up the back... and a tiny apron - one like the waitresses wore in 1950s tearooms - asked to be whipped if people were not happy with his services."

In her autobiography, Mandy (1980) Mandy Rice-Davies described what happened when she arrived at Novotny's party in Bayswater: "The door was opened by Stephen (Ward) - naked except for his socks... All the men were naked, the women naked except for wisps of clothing like suspender belts and stockings. I recognised our host and hostess, Mariella Novotny and her husband Horace Dibbins, and unfortunately I recognised too a fair number of other faces as belonging to people so famous you could not fail to recognise them: a Harley Street gynaecologist, several politicians, including a Cabinet minister of the day, now dead, who, Stephen told us with great glee, had served dinner of roast peacock wearing nothing but a mask and a bow tie instead of a fig leaf."

On 11th July, 1962, Keeler and Mandy Rice-Davies arrived in the United States. She later discovered that her movements were being monitored by the FBI. Seven days later she returned to London.

After the Cuban Missile Crisis Ward told Keeler that he believed John F. Kennedy would be assassinated. He told her and Eugene Ivanov: "A man like John Kennedy will not be allowed to stay in such an important position of power in the world, I assure you of that."

On 28th October, 1962, Stephen Ward introduced Keeler to Michael Eddowes, a lawyer who had become a rich businessman. This included owning Bistro Vino, a chain of restaurants. As Keeler later revealed: "I kept my date with Michael Eddowes but he was far too old for me. He was nearly sixty but her certainly was interested and wanted to set me up in a flat in Regent's Park."

During this period she became involved with two black men, Lucky Gordon and John Edgecombe. The two men became jealous of each other and this resulted in Edgecombe slashing Gordon's face with a knife. On 14th December 1962, Edgecombe, fired a gun at Stephen Ward's Wimpole Mews flat, where Keeler had been visiting with Mandy Rice-Davies.

Keeler and Rice-Davies were interviewed by the police about the incident. According to Rice-Davies, as they left the police station, Keeler was approached by a reporter from the Daily Mirror. "He told her his paper knew 'the lot'. They were interested in buying the letters Profumo had written her. He offered her £2,000."

Two days after the shooting Keeler contacted Michael Eddowes for legal advice about the Edgecombe case. During this meeting she told Eddowes: "Stephen (Ward) asked me to ask Jack Profumo what date the Germans were to get the bomb." However, she later claimed that she knew Ward was joking when he said this. Eddowes then asked Ward about this matter. Keeler later recalled: "Stephen fed him the line he had prepared with Roger Hollis for such an eventuality: it was Eugene (Ivanov) who had asked me to find out about the bomb."

A few days later Keeler met John Lewis, a Labour Party MP and successful businessman at a Christmas party. Keeler later confessed: "I told him about Stephen asking me to get details about the bomb. I told him about Jack. He told George Wigg, the powerful Labour MP with the ear of Harold Wilson. Wigg, who was Jack's opposite number in the Commons, started a Lewis-style dossier; it was the official start of the investigations and questions which would pull away the foundations of the Macmillan government."

Keeler met Earl Felton, a CIA agent, at a New Year party. According to Mandy Rice-Davies, Fenton was a screen-writer who introduced her to Robert Mitchum. The following month Felton contacted Keeler. According to her account: "Stephen had been telling him lies, feeding him false information and indicating that I was spying for the Russians because of my love for Eugene. The message was to leave the country, say nothing about anything I might have seen or heard." Keeler was also told at this time that Eugene Ivanov had fled back to Moscow.

A FBI document reveals that on 29th January, 1963, Thomas Corbally, an American businessman who was a close friend of Stephen Ward, told Alfred Wells, the secretary to David Bruce, the ambassador, that Christine Keeler was having a sexual relationship with John Profumo and Eugene Ivanov. The document also stated that Harold Macmillan had been informed about this scandal.

On 21st March, George Wigg asked the Home Secretary in a debate on the John Vassall affair in the House of Commons, to deny rumours relating to Christine Keeler and the John Edgecombe case. Richard Crossman then commented that Paris Match magazine intended to publish a full account of Keeler's relationship with John Profumo, the Minister of War, in the government. Barbara Castle also asked questions if Keeler's disappearance had anything to do with Profumo.

The following day Profumo made a statement attacking the Labour Party MPs for making allegations about him under the protection of Parliamentary privilege, and after admitting that he knew Keeler he stated: "I have no connection with her disappearance. I have no idea where she is." He added that there was "no impropriety in their relationship" and that he would not hesitate to issue writs if anything to the contrary was written in the newspapers.

Chief Inspector Samuel Herbert interviewed Christine Keeler at her home on 1st April 1963. Four days later she was taken to Marylebone Police Station. Herbert told her that the police would need a complete list of men with whom she had sex or who had given her money during the time she knew Ward. This list included the names of John Profumo, Charles Clore and Jim Eynan.

As a result of his earlier statement the newspapers decided not to print anything about John Profumo and Christine Keeler for fear of being sued for libel. However, George Wigg refused to let the matter drop and on 25th May, 1963, once again raised the issue of Keeler, saying this was not an attack on Profumo's private life but a matter of national security.

On 5th June, John Profumo resigned as War Minister. His statement said that he had lied to the House of Commons about his relationship with Christine Keeler. The next day the Daily Mirror said: "What the hell is going on in this country? All power corrupts and the Tories have been in power for nearly twelve years."

Some newspapers called for Harold Macmillan to resign as prime minister. This he refused to do but he did ask Lord Denning to investigate the security aspects of the Profumo affair. Some of the prostitutes who worked for Stephen Ward began to sell their stories to the national press. Mandy Rice-Davies told the Daily Sketch that Christine Keeler had sexual relationships with John Profumo and Eugene Ivanov, an naval attaché at the Soviet embassy.

On 7th June, Keeler told the Daily Express of her secret "dates" with Profumo. She also admitted that she had been seeing Eugene Ivanov at the same time, sometimes on the same day, as Profumo. In a television interview Stephen Ward told Desmond Wilcox that he had warned the security services about Keeler's relationship with Profumo. The following day Ward was arrested and charged with living off immoral earnings between 1961 and 1963. He was initially refused bail because it was feared that he might try to influence witnesses. Another concern was that he might provide information on the case to the media.

Chief Inspector Samuel Herbert personally interviewed Christine Keeler twenty-four times during the investigation. Other senior detectives had interrogated her on fourteen other occasions. Herbert told Keeler that unless her evidence in court matched her statements "you might well find yourself standing beside Stephen Ward in the dock."

On 14th June, the London solicitor, Michael Eddowes, claimed that Christine Keeler told him that Eugene Ivanov had asked her to get information about nuclear weapons from Profumo. Eddowes added that he had written to Harold Macmillan to ask why no action had been taken on information he had given to Special Branch about this on 29th March. Soon afterwards Keeler told the News of the World that "I'm no spy, I just couldn't ask Jack for secrets."

In a FBI classified memo dated 20th June, 1963, from Alan Belmont to Clyde Tolson referred to the concerns of Defence Secretary Robert McNamara about the John Profumo case. It stated "Mr. McNamara referred to a memorandum from the FBI dated June 14, 1963, advising that Air Force personnel may have had relationships with Christine Keeler." The next section is blacked out but it goes onto say: "McNamara said he felt like he was sitting on a bomb in this matter as he could not tell what would come out of it and he wanted to be sure that every effort was being made to get information from the British particularly as it affected U.S. personnel."

The trial of Stephen Ward began at the Old Bailey on July 1963. Christine Keeler and Mandy Rice-Davies, were both called as witnesses. In their autobiographies, both women rejected this charge. As Rice-Davies pointed out: "Stephen was never a blue-and-white diamond, but a pimp? Ridiculous. And taking money off us! I've already described my finances. As for Christine, she was always borrowing money (from Stephen Ward).

Ronna Ricardo had said that she had sex for money and then gave it to Ward at a preliminary hearing. However, she retracted this information at the trial and claimed that Chief Inspector Samuel Herbert had forced the statement from her by threats against the Ricardo family. According to Philip Knightley: "Ricardo said that Herbert told her that if she did not agree to help them then the police would take action against her family. Her younger sister, on probation and living with her, would be taken into care. They might even make application to take her baby away from her because she had been an unfit mother."

The main evidence against Stephen Ward came from Vickie Barrett. She claimed that Ward had picked her up in Oxford Street and had taken her home to have sex with his friends. Barrett was unable to name any of these men. She added that Ward was paid by these friends and he kept some of the money for her in a little drawer. Christine Keeler claims that she had never seen Barrett before: "She (Barrett) described Stephen handing out horsewhips, canes, contraceptives and coffee and how, having collected her weapons, she had treated the waiting clients. It sounded, and was, nonsense. I had lived with Stephen and never seen any evidence of anything like that... She has never to my knowledge been seen again. I suspect she was spirited out of the country, given a new identity, a new life."

Ward told his defence counsel, James Burge: "One of my great perils is that at least half a dozen of the (witnesses) are lying and their motives vary from malice to cupidity and fear... In the case of both Christine Keeler and Mandy Rice-Davies there is absolutely no doubt that they are committed to stories which are already sold or could be sold to newspapers and that my conviction would free these newspapers to print stories which they would otherwise be quite unable to print (for libel reasons)."

Stephen Ward was very upset by the judge's summing-up that included the following: "If Stephen Ward was telling the truth in the witness box, there are in this city many witnesses of high estate and low who could have come and testified in support of his evidence." Several people present in the court claimed that Judge Archie Pellow Marshall was clearly biased against Ward. France Soir reported: "However impartial he tried to appear, Judge Marshall was betrayed by his voice."

That night Ward wrote to his friend, Noel Howard-Jones: "It is really more than I can stand - the horror, day after day at the court and in the streets. It is not only fear, it is a wish not to let them get me. I would rather get myself. I do hope I have not let people down too much. I tried to do my stuff but after Marshall's summing-up, I've given up all hope." Ward then took an overdose of sleeping tablets. He was in a coma when the jury reached their verdict of guilty of the charge of living on the immoral earnings of Christine Keeler and Mandy Rice-Davies on Wednesday 31st July. Three days later, Ward died in St Stephen's Hospital.

In his book, The Trial of Stephen Ward (1964), Ludovic Kennedy considers the guilty verdict of Ward to be a miscarriage of justice. In An Affair of State (1987), the journalist, Philip Knightley argues: "Witnesses were pressured by the police into giving false evidence. Those who had anything favourable to say were silenced. And when it looked as though Ward might still survive, the Lord Chief Justice shocked the legal profession with an unprecedented intervention to ensure Ward would be found guilty."

At the end of the Ward trial, Newspapers began reporting on the sex parties attended by Christine Keeler and Mandy Rice-Davies. The Washington Star quoted Rice-Davies as saying "there was a dinner party where a naked man wearing a mask waited on table like a slave." Dorothy Kilgallen wrote an article where she stated: "The authorities searching the apartment of one of the principals in the case came upon a photograph showing a key figure disporting with a bevy of ladies. All were nude except for the gentleman in the picture who was wearing an apron. And this is a man who has been on extremely friendly terms with the very proper Queen and members of her immediate family!"

The News of the World immediately identified the hostess at the dinner party as being Mariella Novotny. Various rumours began to circulate about the name of the man who wore the mask and apron. This included John Profumo and another member of the government, Ernest Marples. Whereas another minister, Lord Hailsham, the leader of the House of Lords at the time, issued a statement saying it was not him.

Novotny refused to comment on her activities and the man in the mask remained unidentified. However, Time Magazine speculated that it was film director, Anthony Asquith, the son of former prime minister, Herbert Asquith.

Christine Keeler pleaded guilty to conspiracy to obstruct the course of justice and to perjury and was sentenced to nine months in prison. After she was released she used the money from the News of the World to buy a house for £13,000 in Linhope Street in Marylebone.

In her memoirs Keeler claimed that she was in great demand after all the publicity she had received and had sexual relationships with George Peppard, Maximilian Schell, Warren Beatty and Victor Lownes. She eventually married James Levermore but the relationship did not last.

Mariella Novotny was found dead in her bed in February 1983. It was claimed by the police that she had died of a drug overdose. Christine Keeler later wrote: "The Westminster Coroner, Dr Paul Knapman, called it misadventure. Along with People in Moscow, I still think it was murder. A central figure in the strangest days of my life always believed Mariella would be killed by American or British agents, most probably by the CIA."

In 1983 Keeler published an autobiography, Nothing But. At the time she worked in telephone sales in Fulham. Later she worked for a dry-cleaning business in Battersea. In the early 1990s she moved to the south coast and was employed as a dinner lady at Norton School. A second autobiography, The Truth at Last, appeared in 2001.

Christine Keeler died on 4th December, 2017.

Primary Sources

(1) FBI document (July, 1963)

Reference is made to my letter of June 24, 1963, which you returned to the Assistant Director C. A. Evans on July 2, 1963. At the time you inquired if we had learned what Christine (Keeler) and her friend did in the U.S. when they were here.

It has been learned that Christine Keeler and Marilyn Rice-Davies arrived in the U.S. aboard the SS Niew Amsterdam on July 11, 1962. They registered at the Hotel Bedford, 118 East 42nd Street, New York City, July 11, 1962, and re-registered on July 16, 1962. Hotel records do not show a date of departure; however, they did leave the U.S. on July 18, 1962, by British Overseas Airways Corporation plane.

(2) Mandy Rice-Davies, Mandy (1980)

It is difficult to equate the public image of Christine, as the hard bitten go-getter, with the Christine I knew. She was shy and quiet, domesticated in that she liked to cook and play house, at the same time sweet and amusing company. She had a good sense of humour, not particularly witty because she was never sharp in that way, but light, easy company.

She had not enjoyed a happy childhood, but there was no bitterness about her. She flipped through life, a day, a night at a time, not bothering about what would follow.

Had she been an intellectual, you would have said she led a bohemian existence. She had the way of a waif, infuriating yet always making you feel you must help her. Disorganised to the point of helplessness, she attracted people who were the opposite, who felt they could sort out her practical problems and lift her out of her day-to-day chaos. She was an undemanding friend, happiest with people who made no demands on her. I enjoyed her company and learned never to rely on her for anything.

She liked men and had an unerring eye for what women understand as an absolute bastard. We used to joke that Christine would walk into a room with twenty eligible bachelors and make a beeline for the one out-and-out rotter. She fell in love frequently, passionately and unreservedly. She left herself wide open to being treated badly because she did nothing to protect herself. Often her intensity actually scared the man off after a brief fling and Christine would be left lovesick and forlorn and asking where had she gone wrong. But not for long, and then somebody else was on the scene. At one extreme she was impressed by older, successful men, at the other she had an unhealthy penchant for the flotsam of the demi monde. It was her predilection for West Indians which had led to her introduction to soft drugs. She had a healthy sex drive and assumed that there was but one logical conclusion to sexual attraction.

Although my own experience, when we first met, in no way matched hers, I never questioned her way of life. In the society in which we moved, people did not question each other's behaviour. She had many men friends, some with whom she had once had an affair and many others who were platonic friends. Men were madly attracted to Christine, and remained close to her long after the passionate interlude, had it taken place, was over.

(3) Report by Detective Sergeant John Burrows on his interview of Christine Keeler (January 1963)

She said that Doctor Ward was a procurer of young women for gentlemen in high places and was sexually perverted: that he had a country cottage at Cliveden to which some of these women were taken to meet important men - the cottage was on the estate of Lord Astor; that he had introduced her to Mr John Profumo and that she had an association with him; that Mr Profumo had written a number of letters to her on War Office notepaper and that she was still in possession of one of these letters which were being considered for publication in the Sunday Pictorial to whom she had sold her life story for £1,000. She also said that on one occasion when she was going to meet Mr Profumo, Ward had asked her to discover from him the date on which certain atomic secrets were to be handed over to West Germany by the Americans, and that this was at the time of the Cuban crisis. She also said she had been introduced by Ward to the Naval Attache of the Soviet Embassy and had met him on a number of occasions.

(4) John Profumo, statement (22nd March, 1963)

I understand that in the debate on the Consolidated Fund Bill last night, under the protection of parliamentary privilege, the Hon. Gentlemen the Members for Dudley (George Wigg) and for Coventry, East (Richard Crossman), and the Hon. Lady the Member for Blackburn (Barbara Castle), opposite, spoke of rumours connecting a Minister with a Miss Keeler and a recent trial at the Central Criminal Court. It was alleged that people in high places might have been responsible for concealing information concerning the disappearance of a witness and the perversion of justice.

I understand that my name has been connected with the rumours about the disappearance of Miss Keeler. I would like to take this opportunity of making a personal statement about these matters. I last saw Miss Keeler in December 1961, and I have not seen her since. I have no idea where she is now. Any suggestion that I was in any way connected with or responsible for her absence from the trial at the Old Bailey is wholly and completely untrue.

My wife and I first met Miss Keeler at a house party in July 1961, at Cliveden. Among a number of people there was Doctor Stephen Ward whom we already knew slightly, and a Mr Ivanov, who was an attache at the Russian Embassy.

The only other occasion that my wife or I met Mr Ivanov was for a moment at the official reception for Major Gagarin at the Soviet Embassy.

My wife and I had a standing invitation to visit Doctor Ward.

Between July and December, 1961, I met Miss Keeler on about half a dozen occasions at Doctor Ward's flat, when I called to see him and his friends. Miss Keeler and, I were on friendly terms. There was no impropriety whatsoever in my acquaintanceship with Miss Keeler.

Mr Speaker, I have made this personal statement because of what was said in the House last evening by the three Hon. Members, and which, of course, was protected by privilege. I shall not hesitate to issue writs for libel and slander if scandalous allegations are made or repeated outside of the House.

(5) The Denning Report (1963)

After they got back to the flat Christine Keeler telephoned Mr. Michael Eddowes. (He was a retired solicitor who was a friend and patient of Stephen Ward and had seen a good deal of him at this time. He had befriended Christine Keeler and had taken her to see her mother once or twice.) Mr. Eddowes went round to see her. She told him of the shooting. He already knew from Stephen Ward something of her relations with Captain Ivanov and Mr. Profumo, and he asked her about them. He was most interested and subsequently noted it down in writing, and in March he reported it to the police. He followed it up by employing an ex-member of the Metropolitan Police to act as detective on his behalf to gather information.

(6) Time Magazine (1st May, 1989)

Britain's Minister of War John Profumo, husband of refined movie star Valerie Hobson, has been sharing the sexual favors of teen tart Christine Keeler with Soviet spy Eugene Ivanov . . . Keeler's blond pal Mandy Rice-Davies, 18, declared in court that she had bedded Lord Astor and Douglas Fairbanks Jr. . . . Mariella Novotny, who claims John F. Kennedy among her lovers, hosted an all-star orgy where a naked gent, thought to be film director and Prime Minister's son Anthony Asquith, implored guests to beat him . . . Osteopath and artist Stephen Ward, whose portrait subjects include eight members of the Royal Family, has been charged with pimping Keeler and Rice-Davies to his posh friends. Part of Ward's bail was reportedly posted by young financier Claus von Bulow.

(7) Philip Knightley, An Affair of State (1987)

Christine knew nothing of "cheque book journalism", but she had friends who did: Paul Mann, the racing driver/journalist and Nina Gadd, a freelance writer. Together they convinced her that, if she listened to them, she could make a small fortune. They reminded her that she was constantly broke and that Lucky Gordon was still making her life miserable. They told her they had been in touch with certain newspapers in Fleet Street which were prepared to offer her a great deal of money. This was true. Several newspapers were interested in Christine Keeler, especially when her appearance at the committal hearings of the Edgecombe shooting case at Marlborough Street Court reminded editors of the rumour floating around Fleet Street about her: that she was having an affair with Profumo.

There were problems, of course. The first was the English contempt law. No newspapers could publish anything about Christine's relationship with Edgecombe until his trial was over because the details of it were central to the charge. Next, there were the libel laws. If Christine's memoirs named other lovers, unless there was solid proof that what she said was true, they might sue for defamation. On the other hand most of the news at that time was bad, and a light sexy story of an English suburban girl who could arouse such passions - "I love the girl," Edgecombe had said, "I was sick in the stomach over her" - would certainly appeal to the readers of the Sunday sensational press.

Nina Gadd knew a reporter on the Sunday Pictorial, so on 22 January, with Mandy along to steady her resolve, Christine walked into the newspaper office carrying Profumo's farewell letter in her handbag. The newspaper's executives heard her out, looked at the letter, photographed it and offered her £1,000 for the right to publish it. Christine said she would think it over. She left the offices of the Sunday Pictorial and went straight to those of the News of the World, off Fleet Street. There she saw the paper's crime reporter, Peter Earle. Earle was desperate to have the story - for reasons that will emerge - but Christine made the mistake of telling him that his offer would have to be better than £1,000 because she had been offered that by another newspaper. Earle, who had had long experience of cheque book journalism, told Christine bluntly that she could go to the devil; he was not joining any auction.

So Christine went back to the Sunday Pictorial, accepted its offer and was paid £200 in advance. Over the next two days she told her entire life story to two Sunday Pictorial reporters. They soon saw that the nub of any newspaper article was her relationship with Profumo and Ivanov. It is easy to imagine how the story emerged. Christine was being paid £1,000 for her memoirs. The second slice, £800, was due only on publication. If the story did not reach the newspaper's expectations, Christine would not get it. She was anxious therefore to please the Sunday Pictorial reporters and dredged her memory for items that interested them. The trend of their questions would soon have indicated what items these were.

(8) Anthony Summers, Honeytrap (1987)

On 22 January 1963 came the logical outcome of Christine Keeler's contacts with the Sunday Pictorial, the newspaper that had infiltrated Keeler's circle through her friend Nina Gadd. For a down payment of £200 - and the promise of £800 to come - Keeler told, the Pictorial everything. With the deft help of professional, an accurate draft story was assembled. The truth was told better in this first draft than it ever would be when Fleet Street finally broke into print. Speaking of her relations with Profumo and Ivanov, Keeler said: "If that Russian ... had placed a tape-recorder or cine camera or both in some hidden place in my bedroom it would have been very embarrassing for the Minister, to say the least. In fact it would have left him open to the worst possible kind of blackmail - the blackmail of a spy... This Minister had such knowledge of the military affairs of the Western world that he would be one of the most valuable men in the world for the Russians to have had in their power..."

The article referred to the request that Keeler ask Profumo about nuclear-armed weapons for Germany. Finally, as proof that there really had been an affair, Keeler gave the journalists Profumo's letter of 9 August 1961, addressing her as "Darling". A copy was placed in the safe at the office of the Pictorial. The story was dynamite, but, as is the way with Sunday newspapers, the editors did not rush into print. What with cross-checking, and the need to have Keeler authenticate the final version, nearly three weeks slipped by - time for much skulduggery.

Four days after telling all to the Pictorial, on Saturday 26 January, Keeler had a tiff with Stephen Ward. It happened when Ward, not knowing that Keeler was listening in, had a telephone conversation with Keeler's current flatmate. The Edgecombe shooting incident was proving a nuisance, and he burst out: "I'm absolutely furious with her ... she's ruining my business. I never know what she'll do next, the silly girl..."

Keeler was angry. What she did next was to tell the Profumo story all over again, this time with Ward as the villain of the piece, the man who had made all the introductions. She told the story to the next person who came to the door, who by unhappy chance was an officer in the Metropolitan Police calling to say that Keeler and Rice-Davies would have to appear at John Edgecombe's trial. The detective listened to Keeler, then went back to the office and filed a report. It included all the main elements of the story, along with the allegation that "Dr Ward was a procurer for gentlemen in high places, and was sexually perverted," and the fact that the Pictorial already had the story. The detective's report went to his Inspector, and - given the content - he passed it on to Special Branch, the police unit which liaises with M15.

That same Saturday, Stephen Ward learned from a reporter of the impending story in the Sunday Pictorial. He was the first of the principal male characters to learn of impending disaster. Ward at once demonstrated a loyalty to his friends that none of them would ever show towards him. "I was anxious," he said in his memoir, "to save Profumo and Astor from the consequences..."

Next morning, Monday the 28th, Ward called Lord Astor. The two men met, Astor also took legal advice, then personally took the bad news to the Minister for War. The time was 5.30 p.m.

Profumo's immediate response was remarkable - he urgently contacted the Director-General of M15, Sir Roger Hollis. It was an unusual procedure for a minister of Profumo's rank to call in the head of M15. Yet Hollis was sitting in Profumo's office in just over an hour. Both men, of course, remembered the occasion in 1961 when MI5, through the Cabinet Secretary, asked Profumo to take part in the Honeytrap operation to make Ivanov defect. Now, so far as Hollis could tell, Profumo wanted help in getting a "D Notice" - a Government gag - slapped on the Sunday Pictorial. Hollis failed to oblige.

(9) Christine Keeler, The Truth at Last (2001)

Before the beginning of one of the greatest miscarriages of British justice ever, in early July 1963 I had to go to see Lord Denning at the government offices near Leicester Square. Denning had started hearing evidence on 24 June 1963, and interviewed Stephen three times and talked to Jack Profumo twice. He talked to lots of people - from the prime minister to newspaper owners and reporters, to six girls who knew Stephen.

I was not included in that half-dozen. I found myself a major player in the inquiry and had two interviews with Denning. I was allowed to have a legal representative and Walter Lyons went with me to the polished-wood-panelled offices Denning used. Denning was quietly spoken and asked me all the relevant questions, the ones I had expected. Questions like who had been present with Eugene and Stephen and where and when, and if I knew of any missiles. I answered him honestly. Denning had all the - well, all the ones they had given him - police, M15 and CIA reports before him. He also had Sir Godfrey Nicholson's and Lord Arran's statements.

He knew that Stephen was a spy and that I knew too much. During my two sessions with him I told him all about Hollis and Blunt: how Stephen had politely introduced me and how I had said "hello" and nodded when they visited. I told him all about Sir Godfrey's visit and how I had seen Sir Godfrey with Eugene. He asked me very precisely who had met Eugene and about the visitors to Wimpole Mews. He showed me a photograph of Hollis - it wasn't a sharp shot of him - and asked me to identify him. I told Denning this was the man who had visited Stephen. He showed me a photograph of Sir Godfrey and I also identified him. He did not show me a picture of Blunt for, I suspect, they already knew more than they wanted to know about Blunt. Denning was very gentle about it and I told him everything. This was the nice gentleman who was going to look after me. But I was ignored, side-lined - disparaged as a liar so that he could claim that there had been no security risk. It was the ultimate whitewash.

I told Denning that Stephen had wanted me dead because I could have betrayed them all. I told him I had been entrapped in Stephen's spy ring and had witnessed his meetings with double agents and Soviet spies. I told him I had taken sensitive material to the Russian Embassy. He ignored my evidence that Stephen Ward was a Russian spy and that one of the top men in British intelligence was a Moscow man.

I was a young girl when I met Stephen Ward and not much more than a teenager when I was interviewed by Lord Denning. Like Stephen, he seemed a father figure.

I told him all about Stephen's spying activities and about high society decadence. Denning chose - as with everything in his flawed report - to ignore me for the national interest. I told him about Stephen saying John Kennedy was "too dangerous" and would have to be "put out of the picture". That Kennedy was the main threat to world peace. A few months later Kennedy was killed in Dallas. I was told to be quiet or else. I was terrified.

Fearful about what secrets Stephen had sent to Moscow Centre, when he produced his report Denning had Eugene being introduced to Cliveden with Arran on 28 October 1962, and to Lord Ednam's home on 26 December 1962. He used dates and places to cover up all that happened and denied all the evidence he had from me and others. He wrote his report to have Mandy take over my life and had her living at Wimpole Mews on 31 October 1962. It was rubbish and it introduced her to people and events she knew nothing about. And Mandy made as much capital as she could from that.

(10) Peregrine Worsthorne, The New Statesman (26th February, 2001)

Read as fiction, Christine Keeler's The Truth at Last makes for quite a gripping thriller, and provides more than enough new angles on the familiar story of the 1960s Profumo scandal to make it just worth reading. "New angles" is an understatement: Keeler's story turns the familiar one on its head, and transforms the artist-osteopath Stephen Ward from a charming, persecuted pimp into a sinister and murderous Soviet spymaster controlling not only Anthony Blunt, but also Sir Roger Hollis, then head of MI5.

Other sensational novelties include a walk-on part for Oswald Mosley, the prewar fascist leader, who is numbered among her many famous clients, and the suggestion that my first editor at the Daily Telegraph, Sir Colin Coote, much decorated as a First World War hero, was not quite the silken-haired patriot he seemed. Apparently, it was not only at the Garrick Club that he used to wine and dine Ward, who treated his back. Those innocent meetings, it seems, were merely a cover for hitherto unknown, more conspiratorial encounters.

Nothing is impossible these days. After all, if a Master of the Queen's Pictures can turn out to be a spy, then surely it cannot be ruled out that an editor of the Daily Telegraph could also be one. In any case, now that I come to think of it, there was always something a bit hairy-heeled about Coote - his friendship with Lord Boothby, for example, and the mysterious way he had walked out, quite literally, on his first wife. Rumour had always had it that the two of them, in the 1930s, were having afternoon tea in Brown's - then as now the country set's favourite London hotel - when a glamorous, foreign-looking lady passed by. Coote took one glance and, without saying another word to his wife (whom he never saw again), followed the woman out of the hotel. She became his second wife. I remember her well. She was a Dutch girl whom Coote had not seen since falling in love with her years earlier while he was serving in Flanders during the First World War.

All a bit James Bondish, one has to admit. So perhaps, after all, Keeler's suspicions have some substance. Then, as happens so often in this book, a small detail in the narrative sets alarm bells ringing - in this case, the news that those conspiratorial meetings between Coote and Ward took place in, of all places, a Kenco coffee shop. The thought of Sir Colin Coote, DSO, an archetypal six-foot Edwardian boulevardier, epicure and wine buff, conducting any type of business in a London coffee bar well and truly beggars belief.

Unfortunately, there is much else in Keeler's "truth" that also beggars belief. Take the following passage describing her life with Ward during the Cuban missile crisis. "I spent 48 hours worrying before going back to Wimpole Mews [Ward's consulting rooms] on what was to be a turbulent, landmark day. Eugene [Ivanov, the Soviet military attache] was there. He and Stephen were just off to lunch with Lord Arran, the permanent under-secretary, [with a view to setting up] a summit conference." Lord Arran, known to us all as Boofie, was a delightfully scatty alcoholic peer, and occasional journalist, who later played a central role in the legalisation of homosexuality. He is no more to be confused - except, possibly, in a TV serial - with a permanent under-secretary, the highest rank in the Civil Service, than is the equally eccentric and delightful Earl of Onslow today. As for the summit conference that Boofie was expected to call, it is easier to imagine its location - the bar at White's Club - than its participants, who could not have included Keeler herself.

But I am digressing, because the kernel of the book is the claim that Ward was a (possibly the) senior Soviet spy in London during the late 1950s and 1960s, at the height of the cold war. Keeler portrays him as not just a master spy, but a particularly ruthless one - to the extent that he tried to drown her in the stretch of the Thames that flows beside the famous Cliveden Cottage, lent to Ward by Lord Astor. The reason why he wanted to drown her, it seems, was that she knew too much, having been allowed to listen into all his lengthy conversations about defence matters with Ivanov, Hollis and the Tory MP Sir Godfrey Nicholson. Not that Keeler allowed the attempted murder to worry her overmuch: her life with Ward, and indeed her love (strictly platonic, we are told), seem to have continued without interruption.

Keeler makes no attempt to disguise her life's hedonistic irresponsibility. According to her, she had no choice. What she calls the "diktat" of the Sixties zeitgeist, to which she was powerless to say nay, was "to do anything you wanted" and "to think only of yourself". No regrets on that front. What irks her is the jury's verdict that Ward was guilty of living off immoral earnings; and what she wants to make clear in her book is that the official "establishment" version of the Profumo scandal, drawn up by Lord Denning in the famous report of that name, which damned him as a pimp and her as a tart, did them less than justice.

And, in a way, that is true. Keeler's book does convince one that neither of them were in the sex business for money. But while the alternative role in which she prefers to cast herself - that of a good-time girl out only for kicks - is entirely plausible, the one in which she tries to cast Ward - that of murderous Soviet spymaster - is not. And even if it were, why is she so sure that he would prefer to be remembered as a traitor, rather than a pimp? But Keeler is sure. She writes that she has "never cried so deeply" as when they found Stephen "guilty of living off immoral earnings", and that when later she heard complete strangers in the street "putting Stephen down, calling him dirty names", her hatred of them was "violent and complete". How could the wicked establishment have done him such dirt? She owed it to him to put the record straight; to wipe those naughty words off the slate; to make sure that posterity is never allowed to forget that Stephen Ward was nothing as naughty as a pimp, just a mere traitor.

Can that really be Keeler's motive? A part of me wants to believe in her sincerity; that, on her scale of criminal values, pimping is worse than treason. But there again, a certain scepticism persists, for one can't help remembering her understandably hateful feelings towards Ward after his botched attempt on her life. It is just possible that her book aims not to clear his name, but to blacken it still further.