Young Hot Bloods

At a meeting in France in October, 1912, Christabel Pankhurst told Frederick Pethick-Lawrence and Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence about the proposed arson campaign. When they objected, Christabel arranged for them to be expelled from the organisation. Emmeline later recalled in her autobiography, My Part in a Changing World (1938): "My husband and I were not prepared to accept this decision as final. We felt that Christabel, who had lived for so many years with us in closest intimacy, could not be party to it. But when we met again to go further into the question… Christabel made it quite clear that she had no further use for us." (1)

As Fern Riddell has pointed out: "From 1912 to 1914, Christabel Pankhurst orchestrated a nationwide bombing and arson campaign the likes of which Britain had never seen before and hasn't experienced since. Hundreds of attacks by either bombs or fire, carried out by women using codenames and aliases, destroyed timber yards, cotton mills, railway stations, MPs' homes, mansions, racecourses, sporting pavilions, churches, glasshouses, even Edinburgh's Royal Observatory. Chemical attacks on postmen, postboxes, golfing greens and even the prime minister - whenever a suffragette could get close enough - left victims with terrible burns and sorely irritated eyes and throats, and destroyed precious correspondence." (2)

According to Sylvia Pankhurst: "When the policy was fully underway, certain officials of the Union were given, as their main work, the task of advising incendiaries, and arranging for the supply of such inflammable material, house-breaking tools and other matters as they might require. Women, most of them very young, toiled through the night across unfamiliar country, carrying heavy cases of petrol and paraffin. Sometimes they failed, sometimes succeeded in setting fire to an untenanted building - all the better if it were the residence of a notability - or a church, or other place of historic interest." (3)

The WSPU used a secret group called Young Hot Bloods to carry out these acts. No married women were eligible for membership and they had to pledge to "danger duty". (4) The existence of the group remained a closely guarded secret until May 1913, when it was uncovered as a result of a conspiracy trial of eight members of the suffragette leadership, including Flora Drummond, Annie Kenney and Rachel Barrett. (5)

During the trial Matthias McDonnell Bodkin read extracts from a document headed "Votes for Women" and underneath "YHB". Bodkin claimed that YHB stood for Young Hot Bloods. The label was derived from a taunt thrown at Emmeline Pankhurst in one of the newspapers, which ran: "Mrs Pankhurst will, of course, be followed blindly by a number of the younger and more hot-blooded members of the union". (6) As a result of them being single women one newspaper described the Young Hot Bloods as "a spinsters' secret sect". (7)

Bodkin claimed that the police seized a great number of documents. This included a letter written by an analytical chemist, Edwy Godwin Clayton, Fellow of the Institute of Chemists and a Fellow of the Chemical Society. He also ran his own laboratory and according to Bodkin "put his knowledge and his brain at the Union's disposal for the purpose of carrying out crimes and of producing the reign of terror in London." Receipts for money he had been paid by the union were produced in court. (8)

The most incriminating evidence was a letter sent to Jessie Kenney. Bodkin said: "We did not know until these documents were seized at their offices that they had an analytical chemist in their service – a man who, as we know, written a secret letter which the vain folly of Miss Kenney causes her to leave in her bedroom. In the letter he tells her he had been experimenting, and was on the brink of success. Clayton added "Burn this letter." (9)

During the trial, Rachel Barrett said: "When we hear of a bomb being thrown we say 'Thank God for that'. If we have any qualms of conscience, it is not because of things that happen, but because of things that have been left undone." (10) Barrett was sentenced to six months in prison. She was described by one of the prosecuting barristers at the trial as "a pretty but misguided young woman". (11)

Annie Kenney was sentenced to eighteen months but it was Edwy Godwin Clayton who was treated most harshly. Clayton got twenty-one months. Sylvia Pankhurst pointed out: "He had been purely a voluntary worker for the Union, happy, as he wrote, to give his services to a cause he believed just. His business ruined, he was reduced to great poverty, and was eventually assisted by J. E. Francis of the Athenaeum Press, who paid hom a small wage". (12)

Soon afterwards the The Sheffield Evening Telegraph published an interview a member of the London police force, whose special duty is to deal with the Young Hot Bloods. "There is only one way in which it might be possible to deal with the nuisance, and that would be to shadow all the more notable women connected with the campaign, find out where they live, and watch where they go to throughout the day and night. I don't say that would altogether preclude the commission of crime, but it would certainly result very largely in its prevention.... Several of them have a habit of sleeping here or there, with friends or otherwise, and of securing food in the same way.... Curiously enough, these young hot bloods are not the women who would get the vote if either of the recent bills in Parliament had gone through. They own no property, and are not married women: I don't think some of them are ever likely to be. You can well imagine how incendiarism or destruction by means of bomber appeals to young women… None of them are likely to get the vote, and, personally, I am convinced that they don't care about it. What they want is the excitement and morbid satisfaction of doing something wrong… All this seems to be abetted by a few wealthy individuals, ready to stand bail, to lend a car, or give money as required." (13)

First Arson Attack

It has been argued that this group included Helen Craggs, Olive Hockin, Kitty Marion, Lilian Lenton, Miriam Pratt, Norah Smyth, Clara Giveen, Eileen Casey, Hilda Burkitt, Mary Leigh, Gladys Evans, Olive Wharry, Vera Wentworth, Jessie Kenney, Elsie Howey, Elsie Duval, Olive Beamish, Mary Phillips and Florence Tunks. (14) It would seem that Helen Craggs was the first to try and carry out an act of arson. On 13th July 1912 Craggs and another woman were found by P.C. Godden at one o'clock in the morning outside the country home of the colonial secretary Lewis Harcourt. He went towards them and asked them what they were doing. Craggs, said they were looking round the house. The policeman said, "This is not a very nice time for looking round a house. How did you come here? Where do you come from?" Craggs said that they had been camping in the neighbourhood. The police-constable said he had not seen any encampment. She then said they had arrived by the river. Godden seized Miss Craggs and arrested her, and she was taken into custody. (15)

Helen Craggs appeared at Bullingdon Petty Sessions the next day. According to Votes for Women, "Miss Craggs, who carried a bunch of flowers in the colours, was evidently the centre of much sympathy from the public in the Court." (16) Helen pleaded guilty to the charge of "being in the garden…. For an unlawful purpose, to commit a felony, to unlawfully and maliciously set fire to a house and building belonging to Mr Harcourt". The judge argued that because of the seriousness of the crime - eight people were asleep in the house - bail was refused. (17)

The police suspected that the other woman was Ethel Smyth. She was arrested the next day but was released as "she was able without difficulty to satisfy the Bench completely as to her movements on the night in question." (18) Over fifty years later Norah Smyth confided the truth to her nephew, former diplomat Kenneth Isolani Smyth, that she was with Helen Craggs in the attempt to set fire to Harcourt's house. "He expressed surprise, knowing her love of old paintings and antiques, but Smyth explained that she knew the east wing of the house was uninhabited. It was the only violent action that she undertook as a suffragette." (19)

At her trial it was revealed that a typewritten statement was found in Craggs' handbag: "Sir, it is with a deep sense of my responsibility and a sincere conviction that my action is justifiable that I have taken a serious step in the cause of women's enfranchisement… I deplore that though during the past six years the demand for political liberty for women has become the greatest agitation of the time, politicians were content to see the supporters violently treated and unjustly imprisoned rather than give them the long-delayed and much-needed measure of justice which they demanded." (20)

It was claimed that the two women were carrying a basket and a satchel. These contained "a bottle and two cans, which contained nearly three pounds of inflammable oil, four tapers, two boxes of matches, twelve fire-lighters, nine picklocks, an electric torch, a glass-cutter, and thirteen keys." (21)

Helen Craggs was sentenced to serve nine months with hard labour in Holloway. She went on hunger strike and was force-fed five times over two days. Her health was extremely bad and she was released after eleven days, suffering from internal and external bruising. In 1913 she went to Dublin to train as a midwife and a year later married Dr Alexander McCombie, who was working in the East End of London. (22)

Dublin Theatre Royal

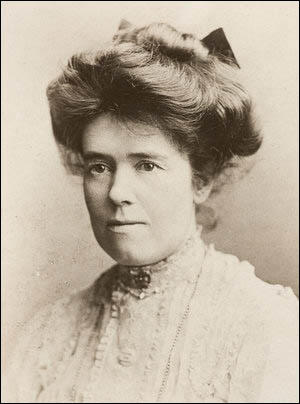

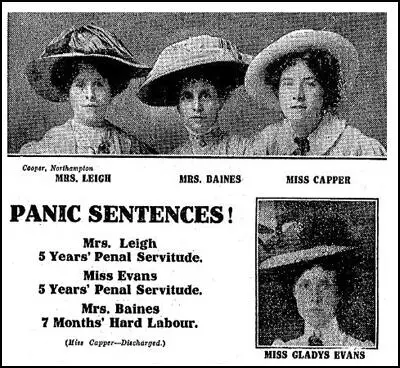

On 16th July, 1912, Gladys Evans and Jennie Baines caught a boat from Holyhead to Dublin and took lodgings in Lower Mount Street. Mary Leigh and Mabel Capper arrived two days later. They were in the city because Herbert Asquith was to give a speech on Home Rule to 4,000 supporters. On the 18th July, Leigh saw Asquith travelling in an open carriage with John Redmond and the Lord Mayor of Dublin. She hurled a hatchet at Asquith, but missed him and hit Redmond on his ear. (22a)

According to John O'Brien, the Chief Marshall: "When abreast of Prince's Street he saw an article flung from the opposite side. He ran round by the horses' head and saw the accused (Mary Leigh) holding on to one of the rails of the carriage. He saw the accused throw the article. He pulled her away from the carriage, when she counteracted him, and started to poke him and tear at him, and struck him a couple of blows in the face." (22b)

Leigh was able to escape and that night, along with Gladys Evans attended a production of the Theatre Royal. As the audience was leaving Joseph Keoth noticed a woman (Evans) throwing a burning rag soaked in paraffin into the projection box at the back of the stalls and running away as if she "expected some explosion". Evans then chucked a handbag filled with gunpowder and matches into a box near the stage. Leigh also threw a burning chair into the orchestra pit. "Several small explosions occurred, produced by amateur bombs made of tin canisters, which, with bottles of petrol and benzine, were afterwards found lying about." (22c)

Evans was arrested at the scene and Leigh at her lodgings the next morning. Jennie Baines and Mabel Capper were also taken into custody. The four women were charged with having "unlawfully conspired with other persons, known, and unknown, to inflict grievous bodily harm and wilful and malicious damage upon property, and to cause an explosion in the Theatre Royal of a nature likely to endanger life or to cause serious injury to property; and that in pursuance of this object they attempted to set fire to the theatre." (22d)

Mary Leigh called no witnesses and addressed the jury from the dock. Votes for Women reported: "The dramatic feature of the day was undoubtedly Mrs Leigh's defence of her case. Slight and frail in outward appearance, spontaneous and alert in manner, she seemed strangely out of place among the burly officials and dull routine of a court of justice. Her masterly cross-examination was so searching as seriously to baffle several witnesses and confuse their evidence on the point of identification, so that the jury found themselves unable to agree that she actually was one of the persons who fired the Theatre Royal. Her speech to the Court was a heroic effort. It was not rhetoric, nor careful arrangements of arguments and telling points, nor even eloquence, that moved the hearts so strongly of all who gazed upon her pleading countenance as she laboured to reiterate the long tale of injustice and evasion meted out to the women who asked for the removal of the disqualification of their sex, and the equally long tale of the steadily successful attainment by men of their political objects in England and Ireland by the sole means of agitation by violence. The pathos of her passionate determination to persevere in her efforts to the emancipation of her womanhood moved the judge himself and many other with deep emotion. Her courage was an amazement even to women who have felt most deeply the things we have at heart." The judge referred to Mary Leigh as "a very remarkable lady of great talents" (22e)

Mary Leigh told them that if they sent her to prison she might not survive the sentence. Mary warned that if convicted she would fight: "she would put her back against the wall, and nothing, not even the whole army of the Government and officials, would bring her to submission. The jury returned guilty verdicts on Mary Leigh and Gladys Evans. Both women were sent to prison for five years because "no more terrible catastrophe could occur in a city than a conflagration at a theatre". Jennie Baines was sentenced to seven months with hard labour, and Mabel Capper was acquitted for lack of evidence." (22f)

The women went on hunger-strike. On 7th August Mary Leigh weighed ninety-five pounds, and Gladys Evans a hundred and fourteen pounds. Before they were force-fed for the first time, their weight had fallen to ninety and ninety-six pounds respectively. After a week Mary's weight had dropped to eighty-six pounds and Gladys had lost only half a pound. Despite having been fed three times a day, Mary had lost ten pounds in eighteen days and the authorities feared that she would die. (22g)

Leigh was released on licence on 20th September 1912 weighing five stones and four pounds.: "When the medical report was received by the Prison Board regarding the grave condition of Mrs Leigh's health, a consultation took place, the Attorney-General being called in. After a long consultation the Board, with the approval of the Attorney-General, recommended her release, and the Lords Junction of the Privy Council, in the absence of the Lord Lieutenant, made the necessary order. The release took place at 6.30 pm. It was the intention to have her removed to the Mater Hospital, but she was conveyed in a cab by two lady friends to a private residence. She is in a state of almost complete collapse, and a specialist will be called in today. Miss Gladys Evans, her fellow-prisoner, who is also being forcibly fed, was examined likewise, but as her condition has not become so far debilitated, no order was made in respect of her. In Mrs. Leigh's case, she had acquired the power of vomiting the food as soon as administered, and her debilitation was due to the consequent starvation." (22h)

As soon as she recovered she began a campaign to get Gladys Evans released: "Mrs Mary Leigh, the suffragette who was released from Mountjoy Convict Prison last week after a hunger strike, sent a letter to a suffragette meeting in Dublin on Sunday stating that if her fellow-prisoner, Miss Gladys Evans, who had been sentenced to five years's penal servitude, is not released during the next few days she (Mrs Leigh) would lead a march on Mountjoy Prison, and the issue would only be decided by victory or death." (22i)

The health of Gladys Evans began to give the authorities concern. Her heartbeat became irregular and she showed signs of "great nervous tension and general breakdown." She also began to resist the feeding process. It was reported she "violently resisted all efforts that were made to feed her and struggled very much". Five wardresses were needed to overcome her, and she had to be strapped by the ankles and wrists into the feeding chair. Evans was released on licence on 3rd October on medical grounds, after fifty-eight days of hunger-striking and being fed by stomach tube eighty-eight times. (22j)

David Lloyd George's House

On 19th February, 1913, an attempt was made to blow up a house which was being built for David Lloyd George, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, near Walton Heath Golf Links. "One device had exploded, causing about £500 worth of damage, while another had failed to ignite." (23) Sir George Riddell who had commissioned the house, wrote in his diary that Lloyd George: "Said the facts had not been brought out and that no proper point had been made of the fact that the bombs had been concealed in cupboards, which must have resulted in the death of 12 men had not the bomb which first exploded blown out the candle attached to the second bomb, which had been discovered, hidden away as it was. He was very indignant." (24) Lloyd George wrote to Riddell and apologised for being "such a troublesome and expensive tenant" and that the WSPU should be made to pay for the damage. (25)

That evening in a speech at Cory Hall, Cardiff, the WSPU leader, Emmeline Pankhurst, declared "we have blown up the Chancellor of Exchequer's house' and stated that "for all that has been done in the past I accept responsibility. I have advised, I have incited, I have conspired". Pankhurst concluded that extreme methods were needed because "No measure worth having has been won in any other way." (26)

Emmeline Pankhurst was arrested and charged with "incitement to commit arson". On 3rd April she was sentenced to three years' penal servitude and immediately went on hunger strike. No attempt was ever made to feed her forcibly and the Prisoners' (Temporary Discharge for Ill Health) Bill (Cat & Mouse Act), which allowed hunger-striking prisoners to be released to recover their health before being returned to prison, was rushed through to ensure that she did not die in prison. (27)

Police records show that the police suspected Olive Hockin and Norah Smyth of being the people who had carried out the attempt to blow up Lloyd George's house. As Elizabeth Crawford has pointed out: "It is clear from the New Scotland Yard reports of the investigation that Olive Hockin's address had been under surveillance. Her absence from home, the manner of her departure and the time of her return are all noted in the police report." (28)

Elsie Duval and Olive Beamish

On the night of 19 March, 1913, Elsie Duval and Olive Beamish, broke into Trevethan, the empty house of Lady Amy White in Egham, Surrey. Her late husband, Field Marshall Sir George White, who became a national hero when he won the Victoria Cross in Afghanistan. They had used a skeleton key to get in and sprinkled petrol in all twenty rooms, and opened windows to accelerate the fire. The fire burned for seven hours and caused £2000 of damage. In the garden's rookery messages were left: "Stop torturing our comrades in prison", "By kind permission of Mr Hobhouse" and "Votes for Women". (28a)

Two women were seen leaving the scene on bicycles. They had been seen arriving at Staines railway station with bicycles fitted with baskets. Just before midnight PC William Pickett was overtaken "at a fairly fast rate" by the women on Staines Bridge. He caught up with the women and spoke to one of them because she had no light on her bicycle. Pickett later identified her as Olive Beamish. (28b) It was assumed that the other woman was her friend, Elsie Duval. (28c)

Elsie Duval and Olive Bamish were also believed to be responsible for burning Sanderstead Station. On 3rd April 1913 Elsie and Olive were approached by a police officer whilst walking in Croydon at 1.45am. They were both carrying leather travelling cases and claimed they were returning from holiday. They were followed by the policeman and decided to drop their cases and run but were caught and arrested for being found with inflammable material with the intention of committing a felony. Both women gave false names: Elsie (Millicent Deane) and Olive (Phyllis Brady). Nine days later they were each sentenced to six weeks' imprisonment. (28d)

Hurst Park Racecourse

Clara Giveen teamed up with Kitty Marion in the arson campaign. They decided that setting fire to the Grand Stand at the Hurst Park racecourse "would make a most appropriate beacon". The women returned to a house in Kew owned by Eileen Casey. (29) A police constable who had been detailed to watch the house, saw the two women return and during the course of the next morning they were arrested. (30)

Giveen's local newspaper reported: "One of the two Suffragettes arrested at Kingston charged in connection with the fire which on Monday did £10,000 damage to the stands at Hurst Park racetrack was Miss Clara Giveen. Miss Giveen who is a lady of independent means, is known in Bexhill, having been associated for some time with the local branch of the WSPU. When arrested at the residence of Dr Casey, Miss Giveen was found lying on a bed in one of the upper rooms, fully dressed. By her side was a copy of the Suffragette. In her room there was a quantity of resin... Miss Giveen in whose room was found the picture of a house burnt down at Eastbourne, was remanded, bail being allowed." (31)

It seems that the police had been watching the homes of women that had been offering help to those women involved in these arson attacks. "On Tuesday two women, Kitty Marion and Clara Giveen, of independent means, were charged at Richmond with loitering, with intent to commit a felony. A policeman who followed them about various streets at Kew at a quarter past two on Monday morning, questioned them, and seen them eventually enter the home of a Dr Casey with a latchkey. A tramcar man identified Marion as being with another women near the racecourse shortly before the fire, and there is other identification evidence. A piece of carpet used to get over the barbed wire of Hurst Park is identified by Marion's landlady as her property." (32)

Their trial began at Guildford on 3rd July, 1913. Giveen and Marion were defended by Ian Macpherson, a Liberal Party member of Parliament, who did not call any evidence. "He pleaded to the jury for an unbiased judgment, and to guard against a certain type of female who felt she was being defrauded by the law of the land of what she regarded as a just and proper - the exercise of the vote." Giveen said no evidence should be passed as they had not been tried by their peers. "Until women were on a jury as well as men, no sentence should be passed upon women." (33)

The main evidence against the women involved a fireman called Brown who claimed he saw Marion and Giveen carrying a portmanteau (a large travelling bag). Nearly two hours later he heard a fire hooter and discovered the fire. Soon afterwards he encountered the same woman without the portmanteau. "They were also seen by a tramcar driver named Middleton, who identified Miss Marion. Later the police found tracks leading to the fence bounding the racecourse, and a large piece of Brussels carpet. At the grand stand were found copies of The Suffragette, showing somebody interested in the question had visited it." (34)

Clara Giveen and Kitty Marion were found guilty and sentenced to three years' penal servitude. They both went on hunger strike and after five days were released under the Cat & Mouse Act. (35) They were taken to a Women's Social and Political Union nursing home, and placed under the care of Dr. Flora Murray and Catherine Pine. (36)

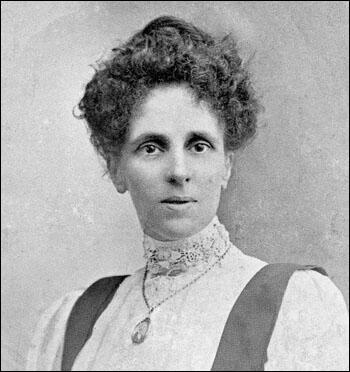

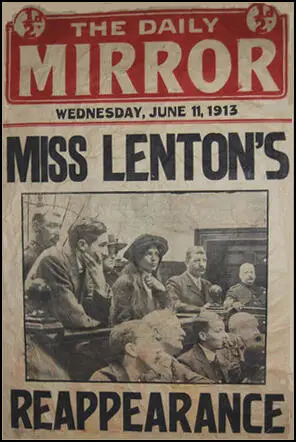

Lilian Lenton and Olive Wharry

In 1913 Lilian Lenton joined forces with Olive Wharry and embarked on a series of terrorist acts. Lenton later explained: "Well, I was at the Suffragette Headquarters and announced that I didn't want to break any more windows but I did want to burn some buildings, and I was told that a girl named Olive Wharry had just been in saying the same thing, so we two met, and the real serious fires in this country started and thereafter I was in and out of prison – six times I think it was – and whenever I was out of prison my object was to burn two buildings a week." (37)

Wharry justified her role in the arson campaign in a statement published in Votes for Women: "How can you expect women to obey laws which they have had no hand in making? Women are classed with imbeciles, aliens, and criminals, and are allowed the rights of citizenship. Many social matters come before Parliament which ought to be dealt with by women, but which are only considered by men. For years women have worked quietly and constitutionally, and it is only because constitutional methods have failed that we have adopted militant methods as the only possible means of getting the vote." (38)

Lenton and Wharry were arrested on 19th February 1913, soon after setting fire to the tea pavilion in Kew Gardens. In court it was reported: "The constables gave chase, and just before they caught them each of the women who had separated was seen to throw away a portmanteau. At the station the women gave the names of Lilian Lenton and Olive Wharry. In one of the bags which the women threw away were found a hammer, a saw, a bundle to tow, strongly redolent of paraffin and some paper smelling strongly of tar. The other bag was empty, but it had evidently contained inflammables." (39)

At her first appearance before the Richmond Magistrates, Olive Wharry created a sensation by throwing a book and some papers at the Chairman. According to one newspaper at her trial she appeared "a prepossessing young woman, who wore a large buttonhole of violets and primroses." In his summing up the judge commented: "that not very long ago it would have been unthinkable that a well-educated, well-bred young woman could have committed such a crime as that. Unfortunately women as a class had forfeited any presumption in their favour of that kind. They knew that well-educated well-bred young women had committed these crimes, and accordingly it was impossible to approach the case from the standpoint from which they would have approached it a few years ago." (40)

On 7th March 1913 Olive Wharry was found guilty and it was reported by the Daily Mirror that "Wharry laughed when sentenced to eighteen months' imprisonment." (41) Wharry made a statement in court where she attempted to explain her actions: "I deny that this court has any jurisdiction over me. A man has the right to be tried by his peers, and so, too, a woman should be tried by women.... Many social matters come before Parliament which ought to be dealt with by women, but which are only considered by men… I am standing for a great principle and morally I am not guilty, though the jury have condemned me, therefore I shall hunger-strike." (42)

It was claimed in court that the tea pavilion "was absolutely destroyed, and a heavy pecuniary loss has thrown upon the two ladies who held the refreshment contract". It was estimated that the loss suffered amounted to £400. (43) It was reported on 26th April that Dr Oliver Robert Wharry was involved in a scuffle when the two solicitors' clerks, employed by the women with the refreshment contract, tried to serve a writ on his daughter. (44) Wharry responded that "she was sorry that the contents of the building was the property of two ladies, she did not know this at the time, but would say to them that this was war, and in a war non-combatants had to suffer." (45)

Olive Wharry went on hunger-strike and Dr Maurice Craig reported to the Home Office that she was "a very frail person, with a very defective circulation... her hands are cold and very blue; her pupils are widely dilated". (46) According to Elizabeth Crawford, the author of The Suffragette Movement (1999): "She was released on 8th April after having been on hunger strike for 32 days, apparently without the prison authorities noticing. His usual weight was 7st 11lbs; when released she weighed 5st 9lbs." (47)

Lilian Lenton was considered too ill to be taken to court. A police report on her behaviour when arrested suggested that she was a difficult prisoner: "Has been in prison before but refuses to give any particulars. General conduct: bad, very defiant. Refuses medical examination - Is rather spare (thin).... Recognised by officers as having been in prison before but name cannot be given. Has taken no food since reception. Smashed up everything in the cell she was first placed in. Removed to a special strong cell. Kept apart from all other prisoners & not allowed to communicate. All privileges suspended." (48)

Lilian Lenton went on hunger-strike and was forcibly fed before being released on 23rd February, 1913. The case caused a great deal of controversy. Reginald McKenna, the Home Secretary, denied that she had been forcibly fed and her illness was due to the effects of her hunger strike. In reality, she had been fed by nasal tube and two hours later the prison doctor reported that he found her "in a very collapsed condition" and "remained for about two hours in a very critical condition". (49)

Lenton's supporters sent a letter to The Times: "She (Lenton) was certainly in imminent danger of death on that Sunday afternoon, but this was not due to her two days' fast, but to the fact that during forcible feeding executed by the prison doctors on the Sunday morning food was poured into her lungs... The plain facts of Miss Lenton's case prove clearly that the food which was forcibly injected into her lung set up a pleuro-pneumonic condition which, but for her youth and good healthy physique, could have ended more seriously. That the prison doctor and the governor recognised immediately what they had done is also obvious. They hurriedly and at the further risk of injury to the patient immediately removed her from the prison, so that at least she should not die there and thus compromise the Home Office, and our horrible prison administration of which they were the instruments." (50)

After she recovered Lenton managed to evade recapture until being arrested in June 1913 in Doncaster and charged with setting fire to to a railway station at Blaby, Leicestershire. She was held in custody at Armley Prison in Leeds. She immediately went on hunger-strike and was released after a few days under the Cat & Mouse Act. The following month she escaped to France in a private yacht. Lenton was soon back in England setting fire to buildings but in October 1913 she was arrested at Paddington Station. Once again she went on hunger-strike and was forcibly fed, but was released when she became seriously ill. (51)

Lilian Lenton was released on licence on 15th October. She escaped from the nursing home and was arrested on 22nd December 1913 and charged with setting fire to a house in Cheltenham: "The two Suffragettes who, minus shoes and stockings, and with their hair falling on their shoulders, were charged at Cheltenham on Monday last week with setting fire to Alstone Lawn, an unoccupied mansion belonging to Colonel De Sales la Terriere, were released from Worcester Goal on Sunday following a hunger strike. Both women refused any information with regard to themselves, but one has been identified as Lilian Lenton, who was at liberty under Cat and Mouse Act. The second prisoner is still unidentified." (52)

After another hunger-and-thirst strike, Lenton was released on 25th December to the care of Mrs Impey in King's Norton. Once again she escaped and evaded the police until early May 1914 when she was arrested in Birkenhead. "Miss Lilian Lenton, the well-known Suffragette, was rearrested at Birkenhead yesterday. She had been staying with friends, and was a Birkenhead detective. Miss Lenton was heavily veiled, and wore a cream jersey and large hat. She will be handed over to Scotland Yard detectives today." (53)

Lilian Lenton was "indicted for feloniously breaking into a dwelling-house near Doncaster with intent to commit a felony and set fire to the same." One newspaper reported: "Mary Temple Beechcroft, said she was 72, and a housekeeper. In June last she was alone in the house, and heard a noise during the night. On going downstairs she saw accused and another, who had already been tried. The police arrived and fire-lighters were found on the stairs… paraffin and cotton wool were also discovered." (54)

The Suffragette provided a detailed account of the trial. "Throughout the trial Miss Lenton, in spite of the fact that she was obviously weak and ill, kept up a continuous address to the jury, which practically drowned the hearing of the case." The prosecutor claimed that her actions could of resulted in the housekeeper. Lenton replied: "This is absolutely ridiculous, because we always look first to see if anyone is there."

Lenton was found guilty and sentenced to 12 months imprisonment. "Although she had been committed for trial several times previously, this is the first time that any sentence has been passed on her. In Court, in spite of the fact that she was weak and ill owing to over four days' hunger and thirst strike, she continued, with a courage that dominated all in Court, to address the jury during the whole of the case, thus rendering the legal proceedings inaudible." Lenton told the judge: "No man who was anything, but a cad can possibly pass judgement on a woman who is charged with breaking laws she has had no hand in making." (55)

Olive Hockin

Police records show that the police suspected Olive Hockin of being the person who had been responsible for the arson attack on the house being built for David Lloyd George, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, near Walton Heath Golf Links. Police kept her under close surveillance and on 12th March 1913, the police raided her flat. They discovered a "suffragette arsenal" that included "a perfect arsenal of implements of destruction, including bottles of corrosive fluid, clippers for cutting telegraph wires, fire lighters, hammers, flints, tools of all descriptions in addition to a number of false motor-car identification plates, etc..." (56)

Olive Hockin was charged with "conspiring with others unknown to set fire to the croquet pavilion, the property of Roehampton Golf Club (26 February), to commit damage to an orchid house at Kew Gardens (8 February) and to cut telephone wires on various dates", and with "placing certain fluid in a Post Office letter-box in Ladbroke Grove (12 March)". (57) At her trial it was disclosed that a copy of the Daily Herald and of The Suffragette, which was found inside the dropped bag had her name and address penciled on them. Her caretaker later identified the handwriting as that of their local newsagents. (58)

At her trial Hockin admitted that she had been drawn into the militant suffrage movement after she became aware of the evils of prostitution. (59) In court it was stated that Hockin had been seen by "a police officer to ride a bicycle along the High Street, Notting Hill, and turn into Ladbroke Road, where the pillar-box stood. When the officer got up to the letter-box he saw some fluid trickling out of the bottom." (60)

In court it was admitted that Olive Hockin had been under surveillance for several weeks and on 26th February, the night of the attack in Roehampton, Hockin was seen to be acting suspiciously. Votes for Women reported: "In the evening a motor-car, driven by a lady, stopped at the house. Some parcels and long rods were taken out of the studio and strapped to the side of the car. The defendant (Olive Hockin) and another lady left in the car at about 10.30." About four o'clock the next morning the witness heard the front door bang and someone pass up the stairs to the studio. Later in the morning Miss Hockin said she was sorry that the door banged, but 'the young lady did not know how to manage the door'. The witness "stated that Miss Hockin did not sleep at the studio on the night of the Roehampton affair." (61)

Mrs Hall, her landlady, pointed out that the following morning Olive Hockin left out two pairs of boots to be cleaned, and only one pair of which belonged to the prisoner. The second pair had mud and grass on them, at the sight of which Mrs Hall remembered reading an article about a fire at the Roehampton Pavilion. Later that day Mrs Hall heard Hockin being visited by two young women carrying gentleman's "dressing-cases". (62)

Olive Hockin claimed she was not guilty of these charges. She also objected to the male dominated justice system: "A court composed entirely of men have no moral right to convict and sentence a woman, and until women have the power of voting I shall continue to defy the law, whether I am in prison or out of it." (63)

Judge Charles Montague Lush formally withdrew the charges relating to the attack on the orchid house, telephone-wire cutting and the pillar-box attack,. His summing-up showed sympathy for Olive Hockin and commented there was no evidence that she was present at Roehampton. Lush also controversially commented that she was a "woman who in her zeal had joined in a cause which she thought was a thoroughly good cause, and she might be right in thinking so." (64) Olive was sentenced to four months imprisonment and ordered to pay half the costs of the prosecution. (65)

Soon after her arrival surveillance photographs of Olive Hockin were taken from a van parked in the prison exercise yard. Olive appears with Margaret Schenke, Jane Short and Margaret Mcfarlane. The images were compiled into photographic lists of key suspects, used to try and identify and arrest Suffragettes before they could commit militant acts. (66)

exercising in the yard of Holloway prison (March 1913)

Olive Hockin threatened to go on hunger strike and it was transferred to the First Division, and agreed to serve her sentence on condition of being permitted to carry on as an artist in prison. (67) Margaret Schenke claimed that she carved the chair in her cell. (68)

Miriam Pratt

Miriam Pratt was working as an assistant teacher when she joined the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) and would sell its newspaper, The Suffragette, on the streets of Norwich. (69) However, she eventually decided to take part in the arson campaign. On 17th May 1913, she set fire to an empty building attached to the Balfour Biological Laboratory for Women, in Storey's Way, Cambridge, with paraffin-soaked cloth. (70) The building was erected in 1884 on for the use of women studying science at Newnham and Girton. The laboratory enabled women to learn about anatomy, dissection, microbiology, zoology, chemical compounds and physics. (71)

Fern Riddell has pointed out why Miriam selected this target: "But what good was a university laboratory, and a university education, if women were refused the right to be awarded their degrees? Although universities permitted women to attend courses and take exams, they were not allowed to graduate, and there was little opportunity for them to use the knowledge they acquired in the world outside the protected college atmosphere. Perhaps it was the unbearable unfairness of this inequality that removed any qualms Miriam and her companions might have felt that night, as they broke and set a fire that consumed a considerable amount of the adjoining building before the alarm was raised." (72)

When the police examined the scene of the fire they found suffrage literature. This was done to show the authorities that the crime had been committed by the WSPU in protest against the government's decision not to give the vote to women. Frank Meeres has pointed out that two buildings in Cambridge had been targeted, "first a new house being built for a Mrs Spencer of Castle Street, then a new genetics laboratory. Suffrage leaflets were found in both. A lady's gold watch was discovered outside the window of the laboratory which had been used to get in.... Blood had been found where the arsonist had cut herself while scraping out the putty around the window; Miriam had a corresponding wound." (73)

Miriam's uncle, William Ward, who she was living with at the time, was involved in the investigation. He suspected the gold watch belonged to Miriam. When confronted by Ward about the matter she admitted that she had carried out the attack. As a result she was arrested and taken to the local police court. The Cambridge Independent Press reported that Miriam Pratt was a "tall, pretty girl", who was "dressed in a light blue corduroy coat, a blue cloth skirt, and black velvet toque trimmed with light blue ribbon." (74)

Miriam Pratt was remanded for eight days before being granted bail. The sureties of £200 was raised by a friend, Dorothy Jewson, a member of the WSPU and the Independent Labour Party. Miriam was suspended from her job at St Paul's National School in Norwich. On 18th July, Miriam attended a protest demonstration held on Norwich Market Place against the Cat and Mouse Act. (75)

Miriam Pratt appeared at Cambridge Assizes in October. She chose to represent herself. The main evidence against her came from her uncle. Miriam asked the judge: "Is it legal for the witness to give evidence of a statement he alleges to have obtained from me not having first cautioned me, he being a police officer?" The judge replied: "That does not disqualify him. He was not acting as a police officer." Miriam asked her uncle: "Don't you think it was your duty as a police officer to caution me?" He admitted "it was my duty, but I was speaking to you as a father would do, and I omitted to caution you." (76)

In her final statement to the court, Miriam admitted her guilt: "I ask you to look again at what has been done and see in it not wilful and malicious damage, but a protest against a callous Government, indifferent to reasoned argument and the best interests of the country. A protest carried to extreme because no other means would avail... show by your verdict today that to fight in the cause of human freedom and human betterment is to do no wrong." (77)

Miriam Pratt was sentenced to eighteen months' hard labour and sent to Holloway Prison. Soon after her arrival surveillance photographs of Miriam were taken from a van parked in the prison exercise yard. The images were compiled into photographic lists of key suspects, used to try and identify and arrest Suffragettes before they could commit militant acts. (78)

Miriam Pratt immediately went on hunger strike. The damage force-feeding had inflicted on Miriam was swift and brutal. The Suffragette reported: "Lord, help and save Miriam Pratt and all those being tortured in prison for conscience sake." (79) Doctors were worried about the impact this was having on her heart and released her and ordered three months' bed rest. (80)

Hilda Burkitt

Hilda Burkitt had been a member of the Women's Social and Political Union since November 1907. Burkitt was in charge of advertising meetings and distributing political material, such as selling Votes for Women. The following year she became a WSPU paid organiser in Birmingham. "Hilda held regular evening meetings in parks and on street corners to bring the movement to attention of residents on their way home from work." (81)

Hilda Burkitt was arrested several times for breaking windows and endured forced-feeding on several occasions. In 1913 she decided to join the WSPU arson campaign. Her first partner was Clara Giveen. On 25th November 1913 Hilda was arrested with Giveen for attempting to set fire to the grandstand at the Headingley Football Ground the property of The Leeds Cricket, Football and Athletic Company. The Yorkshire Evening Post reported that Clara Giveen had "escaped from the supervision of the police in Birmingham, to which town she went on Saturday, just before the expiration of her licence." (82)

Burkitt went on the run before joining up with Florence Tunks, a 22 year-old bookkeeper in Cardiff, to carry out a series of arson attacks. On 11th April 1914 they arrived in Suffolk for two weeks of arson. "They then moved through Suffolk, riding bicycles across the countryside and leaving phosphorus in haystacks, which would combust a day or so after they had left." (83)

On 17th April they bombed the Britannia Pavilion on the pier in Great Yarmouth had been reduced to "a shapeless mass of twisted girders and charred woodwork." The owner of the Pavilion received a letter bearing one word, "Retribution", and a "Votes for Women" postcard was found on the sands with comments about Reginald McKenna, the Home Secretary: "Mr McKenna has nearly killed Mrs Pankhurst. We can show no mercy until women are enfranchised." (84)

Burkitt and Tunks then travelled to Felixstowe where they took a room at Mayflower Cottage, the home of Daisy Meadows, whose father, George Meadows, was a bathing-machine proprietor. Daisy remembered the woman arriving with six cases of luggage and a bicycle. Two days later they said they were going to the theatre in Ipswich. Daisy said in court: "I didn't see them go out and didn't see them again until about five minutes to nine next morning." (85)

Instead of going to the theatre, Burkitt and Tunks, had carried out an arson attack on the Bath Hotel, the oldest in the town. The hotel had been built in 1839 at a time when planners were attempting to establish the Suffolk town as a spa resort. No-one was in the hotel at the time of the fire as it was closed for the season. The cost of the damage was £35,000, estimated to be the equivalent of £2.6m today. They left a few clues: labels on the bushes saying "votes for women" and there was a banner that said "there will be no peace until women get the vote." (86)

George Meadows was near the Bath Hotel when it was set on fire. He saw "two ladies there who were laughing, one was tall and the other short." He identified them as Burkitt and Tunks and they were arrested the next morning at Mayflower Cottage. The police searched their rooms before taking them into custody. They found two boxes of matches, four candles, a glazier's diamond, four copies of The Suffragette newspaper, a lamp, a hammer and pliers." (87)

On 26 May 1914 Hilda Burkitt and Florence Tunks were charged with "feloniously, unlawfully and maliciously" setting fire to two wheat stacks at Bucklesham Farm, worth £340 on 24 April; destroying a stack, worth £485 on 24 April at Levington; and setting fire to the Bath Hotel in Felixstowe, on 28 April. The women refused to answer any questions in court, sat on a table with their backs to the magistrate, and chatted while the evidence against them was presented. (88)

During their trial at Suffolk Assizes the women refused to behave in the appropriate manner. The clerk was reading the the indictment when Burkitt shouted out, "Speak up, please, I can't hear." Asked to plead she replied "I don't recognise the jurisdiction of the Court at all. I don't recognize the Judge, or any of these men." While the Jury were being sworn Burkitt shouted "I object to all these men on the jury." Both women "giggled" and loudly laughed, and cried "No surrender." Tunks commented I don't recognize the Court at all.turned her back to the Court". Tunks turned her back to the Court, but was forcibly brought back by the wardresses. Burkitt shouted: "I am not going to keep quiet: I have come here to enjoy myself. I object to the whole of the jury. I am not going to listen to anything you have got to say." (89)

Richard White, a commander in the Royal Navy, gave evidence that he had been standing outside the Bath Hotel at ten o'clock, just hours before the fire broke out. "I had my suspicions aroused... I knew that suffragettes were about. I had it at the back of my mind that probably that's what they might be." Hilda shouted abuse at Commander White, accusing him of trying to seduce them and threw her shoes at White. (90)

On 29th May, 1914, Hilda Burkitt was sentenced to two years' imprisonment, and Florence Tunks to nine months. Hilda told the judge to put on his black cap "and pass sentence of death or not waste his breath". Tunks "vowed that she would be out of prison before long, and that victory would be hers." (91) In prison Burkitt was force-fed 292 times. (92)

Mary Richardson was in prison with Burkitt and Tunks and wrote a letter about them that appeared in The Suffragette. "In wing C, within calling distance is Hilda Burkitt who is very weak now. She has lost a stone. She is sick with each feeding. She has been fed four times a day for over a fortnight at nine, twelve, four, and eight o'clock. Next to her is Florence Tunks. She has lost twenty-seven and a half-pounds, has had two teeth broken, is generally exhausted, and cannot stand without giddiness for more than a few minutes." (93)

Recently-released prison records detailed how much food was force-fed, the attitude of the prisoner, their overall health and weight and any other occurrences. "Hilda Burkett was generally in good health, apparently, despite regular complaints of chest pain at night (said to be due to indigestion). Her decreasing weight was noted. By the middle of July, her weight had gone down to 98 lbs, 16 lbs below average weight for her height". (94)

Eileen Casey

Eileen Casey had been willing to had provided a safe-house for the Young Hot Bloods. However, with most of the group in prison or living in exile, she decided to start her own arson campaign. On 24th June 1914 she was arrested at Nottingham and had been found with explosives, detonators, fuses and a substantial amount of flammable material as well as guidebooks to local churches. (94a) The 900-year-old Breadsall All Saints' Church had been destroyed on 4th June. Among the treasures lost in the blaze were a 14th-century door, 16th-century ornate carved wooden benches and an Elizabethan altar. The Rev J. A. Whitaker told a Derby Daily Telegraph reporter: "It has been done by suffragettes, I know it has." (94b)

The police suspected that Casey was guilty of destroying All Saints' Church and the planned attempt to burn down Southwell Cathedral. She was held on remand until 8 July at Holloway Prison. After going on a hunger strike she was forcibly fed by nasal tube at least 46 times, both at Holloway and subsequently at Nottingham and Winson Green Prisons. She was sentenced to 15 months imprisonment on 28 July 1914. (94c)

First World War

The British government declared war on Germany on 4th August 1914. Two days later, Millicent Fawcett, the leader of the NUWSS declared that the organization was suspending all political activity until the conflict was over. Fawcett supported the war effort but she refused to become involved in persuading young men to join the armed forces. The WSPU took a different view to the war. It was a spent force with very few active members. According to Martin Pugh, the WSPU were aware "that their campaign had been no more successful in winning the vote than that of the non-militants whom they so freely derided". (95)

The WSPU carried out secret negotiations with the government and on the 10th August the government announced it was releasing all suffragettes from prison. In return, the WSPU agreed to end their militant activities and help the war effort. Christabel Pankhurst, arrived back in England after living in exile in Paris. She told the press: "I feel that my duty lies in England now, and I have come back. The British citizenship for which we suffragettes have been fighting is now in jeopardy." (96)

After receiving a £2,000 grant from the government, the WSPU organised a demonstration in London. Members carried banners with slogans such as "We Demand the Right to Serve", "For Men Must Fight and Women Must Work" and "Let None Be Kaiser's Cat's Paws". At the meeting, attended by 30,000 people, Emmeline Pankhurst called on trade unions to let women work in those industries traditionally dominated by men. She told the audience: "What would be the good of a vote without a country to vote in!". (97)

Young Hot Bloods after 1914

As part of the deal all members of the WSPU were released from prison and pardoned for committing acts of arson. None of them followed the example of Emmeline Pankhurst and joined the recruitment campaign. In fact, most of them were totally against the war. Norah Smyth joined Sylvia Pankhurst in the establishment of the East London Federation of Suffragettes (ELF). Smyth wrote in The Women's Dreadnought that "peace would be the overriding issue in the year to come". (98)

Norah and Sylvia formed a branch of the Women's International League for Peace and Freedom in the East End. The women's hostility to the war resulted in people resigning from the ELF. As Sylvia Pankhurst admitted later: "I felt sorrow in having to tell parents whose sons were at the front that war was wrong and its ideals false… It required an effort to bring myself to do it… I lost old friends and subscribers to our movement." (99)

Olive Hockin also left the WSPU and joined the East London Federation of Suffragettes (ELF). Hockin organised the Poplar branch that she ran from her home at 28 Campden Hill Gardens, Kensington. (100) Hockin continued to work as an artist and produced one of her most important paintings, Pan! Pan! O Pan! Bring Back thy Reign Again Upon the Earth (1914) during this period. (101)

Hockin also joined the Women's Land Army. According to her own account, she had "just walked up to offer my services' to a Dartmoor farmer, after having seen his advertisement for a casual labourer." She saw his wife first who commented: "Well really! You must come in and tell me about it. I am afraid my husband only laughs at the idea. He says that a woman about the place would be more trouble than she is worth, and we quite made up our minds that no woman could possibly do the work!"' In 1918 she published her own account of her experiences, Two Girls on the Land: Wartime on a Dartmoor Farm. (102)

Helen Craggs went to Dublin to train as a midwife and in 1914 married Dr Alexander McCombie, who was working in the East End of London. (103) Helen qualified as a pharmacist in order to act as her husband's dispenser. (104) Hilda Burkitt married Leonard Mitchener in 1916, and ran a café in St Albans. (105) Florence Tunks studied for a certificate in nursing between 1915 and 1918 at the Derbyshire Royal Infirmary in Derby and qualified as a nurse in London in 1923. (106)

Clara Giveen married Philip Brewster (born 8th November 1889, Henfield, Sussex), the brother of the suffragette Bertha Brewster on 8th December 1914, at St Michael's & All Angels Church, Summertown, Oxford. (107) Brewster was a pacifist and became a conscientious objector during the First World War. They were living in Gray's Inn Road when he was conscripted in 1916 and within a month he was convicted for "disobeying in such a manner as to show wilful defiance of authority and lawful co mmand of his superior officer in the execution of his office." He was sentenced to two years' hard labour which was served in Wormwood Scrubs and Wandsworth prisons. (108)

Olive Wharry was released from prison into the care of Flora Murray on 10th August, 1914. Wharry told the Aberdeen Evening Gazette that she was a "physical wreck". Her eyes were "sunken", her face was pale, her tongue was "blistered and coated" and she spoke with "much difficulty and pain", Wharry had eaten no food and only taken a few drops of water, and felt "rather nervous, and not in a fit condition to tell you everything". (109)

Olive returned to the family home in Holsworthy in North Devon. Olive resumed her art career and exhibited some etchings in an exhibition of work by Devon artists at Exeter Museum in 1917. Olive took an active life in the parish and is reported as taking part in Amateur Dramatics and giving lectures. Later she became secretary of the Launceston and District Women's Unionist Association. (110)

Miriam Pratt, like her friend Dorothy Jewson, left the WSPU over its support of the First World War. She moved back to Norwich and on 19th May 1915 married Bernard Francis, a political activist who had been a member of the Men's League For Women's Suffrage. At the beginning of the First World War Francis had joined the Royal Engineers and eventually reached the rank of Lieutenant. (111)

William Ward must have forgiven Miriam because when he died in 1936 she inherited a half share of his property. Miriam moved to London where he worked as an Assistant Company Secretary. but kept in contact with her relatives in Norwich until her death at Horton Hospital in Epsom, Surrey on 24 June 1975. (112)

Kitty Marion was also one of those members of the Women's Social and Political Union who disagreed with the policy of ending militant activities. She resumed her career as an actress but continued to campaign for the vote. As she had been born in Germany, the government decided to deport her from Britain. After protests from figures such as Constance Lytton and Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, she was allowed to go to the United States. (113)

Like other members of the WSPU, Mary Leigh began to question the leadership of Emmeline Pankhurst and Christabel Pankhurst. These women objected to the way that the Pankhursts were making decisions without consulting members. Leigh now joined the East London Federation of Suffragettes (ELF). In October 1913 Leigh was badly injured during scuffles with the police at an ELF meeting at Bow Baths. (113a)

During the First World War she applied for war service, but was rejected because of her criminal record. Using her maiden name, Brown, she gained a place on an RAC course to train as an ambulance driver. Later she worked at the New Zealand Expeditionary Force Hospital in Surrey. (113b)

After the war Mary Leigh joined the Labour Party and every year she made the pilgrimage to Morpeth, Northumberland, to tend the grave of Emily Wilding Davison. She continued to campaign for the vote for women after the passing of the limited 1918 Qualification of Women Act. In 1921, while being arrested for chalking the pavement advertising a meeting, she gave a policeman a black eye and went to prison. (113c)

According to her biographer, Michelle Myall: "She apparently took part in the first Aldermaston march (1958), and as a committed socialist regularly attended the May day processions in Hyde Park. She was a founder of the Emily Wilding Davison lodge, a memorial to her suffrage comrade who died after throwing herself under the hooves of the king's horse at the 1913 Epsom Derby. Every year Mary Leigh made the pilgrimage to Morpeth, Northumberland, to tend Davison's grave. In later years she continued to recall with pride her days in the WSPU, and stood by her actions as a suffragette." (113d)

As part of the deal all members of the WSPU were released from prison and pardoned for committing acts of arson. Eileen Casey became a gardener at Kew Gardens. From 1923 to 1940 she moved to Japan to teach English. When the Second World War broke out she moved to Australia where she became a translator for the Board of Censors. Casey also resumed her friendship with Edith How-Martyn who had emigrated to Australia. Casey moved back to England in 1951 and worked as a cleaning lady. (113e)

On 28th March, 1917, the House of Commons voted 341 to 62 that women over the age of 30 who were householders, the wives of householders, occupiers of property with an annual rent of £5 or graduates of British universities. MPs rejected the idea of granting the vote to women on the same terms as men. Emmeline Pankhurst and Christabel Pankhurst now dissolved the Women's Social & Political Union and formed The Women's Party. Its twelve-point programme included: (i) A fight to the finish with Germany. (ii) More vigorous war measures to include drastic food rationing, more communal kitchens to reduce waste, and the closing down of nonessential industries to release labour for work on the land and in the factories. (iii) A clean sweep of all officials of enemy blood or connections from Government departments. Stringent peace terms to include the dismemberment of the Hapsburg Empire." (114)

After the passing of the Qualification of Women Act the first opportunity for women to vote was in the General Election in December, 1918. Several of the women involved in the suffrage campaign stood for Parliament. Only one, Constance Markiewicz, standing for Sinn Fein, was elected. Lilian Lenton later recalled: "Men had a vote at 21, all men. Women only had a vote when they were 30, and then only if they were householders or the wives of male householders. Personally, I didn't vote for a very long time because I hadn't either a husband or furniture." (115)

Lenton was appalled by the decision to dissolve the WSPU before votes for all women had been achieved. Lenton joined the Women's Freedom League (WFL) who employed her as a travelling organizer. Lenton also wrote for the WFL newsparer, The Vote and toured the country making speeches in favour of all women getting the vote. She was also editor of the WFL's The Women's Bulletin for eleven years. (116)

In July 1925, Lenton spoke at a meeting in Clyde. "Many of the questions the speaker (Lilian Lenton) is asked: several are irrelevant, many simply argumentative, whilst others show a real desire for information and understanding. We have the young men who fear the competition of women in the labour market, alleging that because of it they are unemployed – on what the woman is to live they neither know nor care; and others openly evince apprehension lest, when a woman can earn a decent living, her desire for the ties of matrimony may diminish, and loudly answer in the affirmative when asked if they like the idea that a woman is dependent upon them. Not few in number are the youths of about 16 who assert our "mental and physical" inferiority to the male sex." (117)

After 1925 Lilian Lenton became financial secretary of the National Union of Women Teachers. She was a member of the Status of Women Committee and the honorary treasurer of the Suffragette Fellowship. (118) She also gave several interviews on her time in the Women's Social and Political Union. This included two on the BBC: Charlotte March and Lilian Lenton: Militant Suffragettes (119) and Lilian Lenton explains the Cat and Mouse Act (120).

Primary Sources

(1) Sylvia Pankhurst, The Suffrage Movement (1931).

In December 1911 and March 1912, Emily Wilding Davison and Nurse Pitfield had committed spectacular arson on their own initiative, both doing their deeds openly and suffering arrest and punishment. In July 1912, secret arson began to be organised under the direction of Christabel Pankhurst. Women, most of them very young, toiled through the night across unfamiliar country, carrying heavy cases of petrol and paraffin. Sometimes they failed, sometimes succeeded in setting fire to an untenanted building - all the better if it were the residence of a notability - or a church, or other place of historic interest. Occasionally they were caught and convicted, usually they escaped.

(2) Votes for Women (2nd August 1912)

In the early hours of the morning of July 13, P. C. Godden, of the Oxfordshire Constabulary, was on duty in Nuneham Park when his attention was attracted by two ladies who were standing up close to the wall of Nuneham House, and he went towards them and asked them what they were doing. One of the ladies, Miss Craggs, said they were looking round the house. The policeman said, "This is not a very nice time for looking round a house. How did you come here? Where do you come from?"

Miss Craggs said that they had been camping in the neighbourhood. The police-constable said he had not seen any encampment. She then said they had arrived by the river. The police-constable having asked them to give an account of themselves, and receiving no satisfactory account from his view, decided to arrest, if he could, the two ladies. He seized Miss Craggs and arrested her, and she was taken into custody. The other lady escaped. The officer found on the scene of this meeting and struggle which he had with Miss Craggs the basket and satchel produced.

In the receptacles there were discovered, by later examination, a bottle and two cans, which contained nearly three pounds of inflammable oil, four tapers, two boxes of matches, twelve fire-lighters, nine picklocks, an electric torch, a glass-cutter, and thirteen keys.

(3) Votes for Women (26th July 1912)

Miss Helen Craggs, who was arrested in Nuneham Park on July 13, and remanded in custody, appeared at the Bullingdon Sessions at Oxford on Saturday last.

The court was crowded with Suffragists and sympathisers, and several people were ready to stand bail to any amount required. This was, however, not allowed, in spite of the fact that, as the magistrates were no doubt aware, no Suffragist prisoner has ever failed to appear; and with an extra-ordinary prejudging of the case, which almost amounts to contempt of his own Court, the chief magistrate expressed his opinion that an "atrocious crime had been attempted."

Miss Craggs, who carried a bunch of flowers in the colours, was evidently the centre of much sympathy from the public in the Court….

Miss Helen Craggs… was charged with being found at 1 a.m. on July 13 upon a garden in the occupation of Mr Lewis Harcourt, M.P., for an unlawful purpose, to wit, to commit a felony, to unlawfully and maliciously set fire to a house and building belonging to Mr. Harcourt.

Mr Walsh applied for bail and remarked that any amount would be forthcoming. He reminded the Bench that Miss Craggs had been in prison for a week. In this case there had been no previous conviction, and the prisoner was prepared to give the magistrates an undertaking that meantime she would not engage in any unlawful act or in any work whatsoever connected with the Suffrage movement….

Dr Ethel Smyth, the well-known composer and Suffragist, was arrested on Tuesday last at her house, The Coign, Woking, on a charge of being concerned in an attempt to burn down Mr Lewis Harcourt's house in Oxford. According to reports in the press, Dr Smyth is confident of being able to prove an alibi.

(4) Votes for Women (2nd August 1912)

Miss Ethel Smyth, of Woking, the well-known composer, who was arrested some days later on a charge of complicity in the same offence, was discharged at a special session held on July 26, but earlier than the other proceedings, to which the Press representatives were not admitted. It is understood that the magistrates apologized to Dr Smyth for her detention, and she was able without difficulty to satisfy the Bench completely as to her movements on the night in question. It is not surprising that none of the witnesses was able to identify her!

(5) Votes for Women (2nd August 1912)

Miss Helen Craggs – the ardent worker for the Cause who thought of nothing of a leap from roof to roof over a perilously deep drop in order to get the necessary message of "Votes for Women" into Mr Churchill's meeting some time ago – is an admirable example of the criminal folly of the Liberal Government – criminal folly because any man, save those who were absolutely blinded by party, would know how to put to better use such courageous and earnest youth.