Elsie Duval

Elsie Diederichs Duval, the daughter of Emily Duval and Ernest Duval, was born in Battersea on 19th February 1893. Her mother gave birth to eight other children: Ernest (1882), Victor (1885), Walter (1887), Barbara (1888), Norah (1891), Winifred (1895), Gurney (1897) and Ivy (1901). The family lived at 52 Wycliffe Road, Battersea. (1)

Her mother was a supporter of women's suffrage and she joined the Women Social & Political Union (WSPU) in 1906 but left for the Women's Freedom League (WFL) in 1907 where she served as chair of the Battersea branch. Her older sister, Barbara Duval also joined the WFL. (2)

In January 1908 Emily Duval was sentenced to one month's imprisonment after taking part in a deputation to H. H. Asquith, the prime minister, at his home at Cavendish Square. (3) Later that year Emily Duval was in trouble with the courts again: "The Suffragettes have started on a new campaign, that of publicly protesting against the trial of voteless women by man-made laws. In all the London courts suffragettes appeared, and made their protests, being removed in all cases without force. Mrs Emily Duval championing a woman charged with disorder and obscene language. 'Take her out,' said Mr Plowden; 'I cannot have this disturbance.' She went quietly." (4)

Duval Family and Women's Suffrage

On 28th October, 1908, Emily and her daughter Barbara were both arrested after taking part in a demonstration outside the House of Commons. (5) They were both charged with disorderly conduct. Emily paid her fine and Barbara was released after promising to refrain from further militancy until she was twenty-one. At her trial, Emily was described as "a lady agitator who was bringing up her daughter to be a lady agitator". (6)

On 13th January 1910, Elsie's brother, Victor Duval, formed the Men's Political Union for Women's Enfranchisement (MPU). Elsie helped her brother run the office of the MPU. (7) Duval later explained that "The society was formed as a result of a growing conviction among men, as well as women, that the delay in removal of the sex disqualification from the Parliamentary franchise was due to the determined indifference of the Government rather than to any considerable opposition in the country." (8)

In a leaflet published later that year the MPU pointed out that it would oppose all governments in power until such time as the franchise is granted. The MPU outlined the methods it would use: "Vigorous agitation and the education of public opinion by all the usual methods, such as public meetings, demonstrations, debates, distribution of literature, newspaper correspondence and deputations to public representatives." (9)

Women's Social and Political Union

In November 1911 Emily Duval left the Women's Freedom League because she did not feel it was militant enough and rejoined the Women Social & Political Union (WSPU). (10) Elsie, now aged 18, also joined the WSPU. A few days later she was arrested for the first time on the charge of obstructing the police. According to Elizabeth Crawford "she was discharged and immediately volunteered and was accepted by the WSPU for the next militant protest." (11)

Elsie's mother was now fully committed to militant action and early in 1912 was sentenced to two weeks' imprisonment for window smashing. At her trial Emily commented: "It's no use saying much in this court of injustice. I am prepared to die for our cause." (12) On 26th March, 1912, Emily Duval received a six months sentence, which was spent in Winson Green Prison. Emily joined the hunger-strike that was taking place and was force-fed, and in July was released and taken to a nursing home. (13)

In July 1912 Elsie Duval broke two windows at Clapham Common Post Office. At the South-Western Court and fined 40s and 12s 6d damages or a month's imprisonment. She informed the magistrate that she did it as a protest against the forcible feeding of her mother in prison. (14) The magistrate replied: "Do you imagine you could by such conduct, you silly girl, influence this Government, or any other government." (15) Elsie Duval refused to pay the fine and was imprisoned. The court ruled that her "state of mind to be inquired into". While in prison she was forcibly fed nine times by two doctors and nine warders on each occasion. (16)

Young Hot Bloods

At a meeting in France in October, 1912, Christabel Pankhurst told Frederick Pethick-Lawrence and Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence about the proposed arson campaign. When they objected, Christabel arranged for them to be expelled from the organisation. Emmeline later recalled in her autobiography, My Part in a Changing World (1938): "My husband and I were not prepared to accept this decision as final. We felt that Christabel, who had lived for so many years with us in closest intimacy, could not be party to it. But when we met again to go further into the question… Christabel made it quite clear that she had no further use for us." (17)

As Fern Riddell has pointed out: "From 1912 to 1914, Christabel Pankhurst orchestrated a nationwide bombing and arson campaign the likes of which Britain had never seen before and hasn't experienced since. Hundreds of attacks by either bombs or fire, carried out by women using codenames and aliases, destroyed timber yards, cotton mills, railway stations, MPs' homes, mansions, racecourses, sporting pavilions, churches, glasshouses, even Edinburgh's Royal Observatory. Chemical attacks on postmen, postboxes, golfing greens and even the prime minister - whenever a suffragette could get close enough - left victims with terrible burns and sorely irritated eyes and throats, and destroyed precious correspondence." (18)

According to Sylvia Pankhurst: "When the policy was fully underway, certain officials of the Union were given, as their main work, the task of advising incendiaries, and arranging for the supply of such inflammable material, house-breaking tools and other matters as they might require. Women, most of them very young, toiled through the night across unfamiliar country, carrying heavy cases of petrol and paraffin. Sometimes they failed, sometimes succeeded in setting fire to an untenanted building - all the better if it were the residence of a notability - or a church, or other place of historic interest." (19)

The WSPU used a secret group called Young Hot Bloods to carry out these acts. No married women were eligible for membership and they had to pledge to "danger duty". (20) The existence of the group remained a closely guarded secret until May 1913, when it was uncovered as a result of a conspiracy trial of eight members of the suffragette leadership, including Flora Drummond, Annie Kenney and Rachel Barrett. (21)

Elsie Duval became a Young Hot Blood. She was paired up with Olive Beamish. On the night of 19 March, they broke into Trevethan, the empty house of Lady Amy White in Egham, Surrey. Her late husband, Field Marshall Sir George White, who became a national hero when he won the Victoria Cross in Afghanistan. They had used a skeleton key to get in and sprinkled petrol in all twenty rooms, and opened windows to accelerate the fire. The fire burned for seven hours and caused £2000 of damage. In the garden's rookery messages were left: "Stop torturing our comrades in prison", "By kind permission of Mr Hobhouse" and "Votes for Women". (22)

Two women were seen leaving the scene on bicycles. They had been seen arriving at Staines railway station with bicycles fitted with baskets. Just before midnight PC William Pickett was overtaken "at a fairly fast rate" by the women on Staines Bridge. He caught up with the women and spoke to one of them because she had no light on her bicycle. Pickett later identified her as Olive Beamish. (23) It was assumed that the other woman was her friend, Elsie Duval. (24)

Elsie Duval and Olive Bamish were also believed to be responsible for burning Sanderstead Station. On 3rd April 1913 Elsie and Olive were approached by a police officer whilst walking in Croydon at 1.45am. They were both carrying leather travelling cases and claimed they were returning from holiday. They were followed by the policeman and decided to drop their cases and run but were caught and arrested for being found with inflammable material with the intention of committing a felony. Both women gave false names: Elsie (Millicent Deane) and Olive (Phyllis Brady). Nine days later they were each sentenced to six weeks' imprisonment. (25)

Elsie's boyfriend Hugh Franklin had also been arrested and found guilty of setting fire to a railway carriage at Harrow and was serving a six month sentence for arson. Duval, Beamish and Franklin all went on hunger-strike. Elsie suffered 17 days of force-feeding. (26) They all became seriously ill and on 28th April became the first people to be released under the Cat and Mouse Act. (27) On 16th May it was reported by The Daily Herald that they "had failed to return to prison on the date named, and the police are now searching for them." (28)

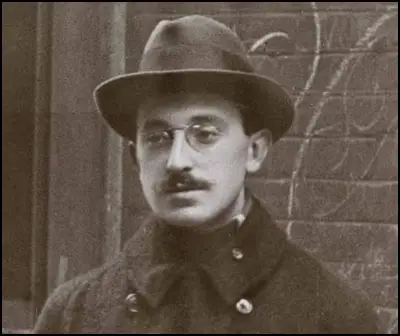

The newspapers were highly critical of the legislation: "The futility of what has earned the name of the 'Cat and Mouse Act' is already demonstrated. Four Suffragist prisoners who were released after hunger striking have not returned to prison on the expiration of their period of grace.... The Special Branch of Scotland Yard has circulated the following description of Franklin: 'Wanted for failing to return to Wormwood Scrubs Prison on May 12th as required by the conditions of an order under the Prisoners' Temporarily Discharge for Ill-Health Act. Hugh Arthur Franklin, aged twenty-six years, height 5ft 8ins, sallow complexion, hazel eyes, dark hair, slight dark moustache, of Jewish appearance, wearing pince-nez." (29)

The Women Social & Political Union (WSPU) issued a statement that said: "For the moment while the cat is about the mice are away and it will be some little time before they allow themselves to be caught. The fact is, that we shall make the Act as ridiculous as anything the Government has done to frustrate our movement, and we have many things in store of which they little dream." (30)

After being released under the Cat and Mouse Act, Elsie Duval escaped with her boyfriend, Hugh Franklin, to Belgium and stayed in Brussels. She received a letter from Jessie Kenney that said: "Miss Pankhurst thinks it would be better for you to stay where you are for the time being and until you get stronger." Elsie got a job in Germany as a governess for 10 months. She then spent three months in Brussels learning French and doing office work, followed by two months in Switzerland." (31)

First World War

The British government declared war on Germany on 4th August 1914. Two days later, Millicent Garrett Fawcett, the leader of the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies declared that the organization was suspending all political activity until the conflict was over. Fawcett supported the war effort, but she refused to become involved in persuading young men to join the armed forces. The Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) took a different view to the war. It was a spent force with very few active members. According to Martin Pugh, the WSPU were aware "that their campaign had been no more successful in winning the vote than that of the non-militants whom they so freely derided". (32)

The WSPU carried out secret negotiations with the government and on the 10th August the government announced it was releasing all suffragettes from prison. In return, the WSPU agreed to end their militant activities and help the war effort. Christabel Pankhurst, arrived back in England after living in exile in Paris. She told the press: "I feel that my duty lies in England now, and I have come back. The British citizenship for which we suffragettes have been fighting is now in jeopardy." (33)

Elsie Duval and Hugh Franklin were now free to returned to England. Duval applied to work with Louisa Garrett Anderson and Flora Murray in a hospital in Claridge Hotel in Paris. The offer was not accepted and she took part in the "Woman's Right to Serve"procession in July 1915. (34) On 28th September 1915 she married Hugh Franklin in the West London Synagogue. During the war he supported anti-war groups such as the No-Conscription Fellowship. (35)

In 1918 the Qualification of Women Act was passed in February, 1918. The Manchester Guardian reported: "The Representation of the People Bill, which doubles the electorate, giving the Parliamentary vote to about six million women and placing soldiers and sailors over 19 on the register (with a proxy vote for those on service abroad), simplifies the registration system, greatly reduces the cost of elections, and provides that they shall all take place on one day, and by a redistribution of seats tends to give a vote the same value everywhere, passed both Houses yesterday and received the Royal assent." (36)

The Act extended the franchise in parliamentary elections, to men aged over 21, whether or not they owned property, and to women aged over 30 who resided in the constituency or occupied land or premises with a rateable value above £5, or whose husbands did. At the same time, it extended the local government franchise to include women aged over 21 on the same terms as men. As a result of the Act, the male electorate was extended by 5.2 million to 12.9 million. The female electorate was 8.5 million. Women now accounted for about 39.64% of the electorate. (37)

As Elsie Duval was only 25 years old she did not get what she had fought so hard to achieve. She was also in bad health. This was partly due to her experience of force-feeding in prison but also because of heart problems caused by septic pneumonia which she contracted during the 1918 influenza epidemic. (38)

Elsie Duval died of heart failure at her father-in-law's home on 1st January 1919. (39)

Primary Sources

(1) The Reynolds Newspaper (7th July 1912)

"Do you imagine you could by such conduct, you silly girl, influence this Government, or any other government," said Mr Francis at the South-Western Court, to Elsie Duval, aged 20, of Park Road, Wandsworth, who broke two windows at Clapham Common Post Office during a suffragist raid.

(2) The Lakes Herald (12th July 1912)

Elsie Duval, twenty, of Park Road, Wandsworth, was at South-Western Police Court, London, on Thursday, fined 40s and 12s 6d damages or a month's imprisonment for breaking the windows of the Clapham Common Post Office. She informed the magistrate that she did it as a protest against the forcible feeding of her mother in prison. Mr Francis said she was a silly little girl, and remarked that the Government would certainly not be influenced by any such action.

(3) The Sunderland Daily Echo (12th April 1913)

At Croydon Police Court today, Phyllis Brady, 23, and Millicent Deane, 23, were each sentenced to six weeks' imprisonment in the second division on a charge of being suspected persons, found loitering, and in possession of a quality of inflammable materials supposed for the purpose of committing felony at Links Road, Mitcham.

The police stated that the women were arrested at two o'clock in the morning, and in parcels they carried were necessary materials to cause a very effective fire. It was stated that Deane's correct name was Elsie Duval, of Wandsworth.

(4) West Sussex Gazette (17th April 1913)

The two young women who chose to be known as Phyllis Brady and Millicent Dean, came again before the Croydon Magistrates on Saturday on charges of being found at Mitcham in the procession of inflammables. They had refused their proper names and addresses, for which reason they had not had bail.

"Brady" looked very ill, and languidly sank into the seat in the dock. It appeared that for the seven days she had been hunger-striking, and had eight times been forcibly fed.

The evidence given last week was repeated. The women were out at two in the morning carrying portmanteaux. To the constable who stopped them in Links Road, they said they had just returned from their Easter holiday at Exeter. Being followed, they dropped the "holdalls" and ran, and "Brady" was caught. The portmanteaux, of the weekend type, were crammed with combustibles, including tins of paraffin, matches, candles, fire-lighters, cotton wool, etc.

"Brady" gave as her reason for reticence that she had come from the provinces, and that, to disclose her real name would be to prevent her obtaining employment in the future…

The story of how "Dean" was caught was told for the first time. After evading the constable sent out on a bicycle saw her talking to the carman in Church Street, Croydon, and arrested her on suspicion. She now described herself as Elsie Duval, of 37, Park Road, Wandsworth.

Each prisoner was sent to six weeks' imprisonment in the second division. The Court was crowded with women sympathisers, but there were no "scenes".

(5) The Daily Herald (16th May 1913)

Five of the prisoners released temporarily under the "Cat and Mouse Act" have failed to return to prison on the date named, and the police are now searching for them. They are Hugh Arthur Franklin, Annie Bell, Phyllis Brady, Elsie Duval (alias Millicent Dean) and Ella Stevenson (alias Ethel Slade).

(6) The Western Chronicle (16th May 1913)

The futility of what has earned the name of the "Cat and Mouse Act" is already demonstrated. Four Suffragist prisoners who were released after hunger striking have not returned to prison on the expiration of their period of grace. The names of the missing prisoners.

The Special Branch of Scotland Yard has circulated the following description of Franklin: "Wanted for failing to return to Wormwood Scrubs Prison on May 12 th as required by the conditions of an order under the Prisoners' Temporarily Discharge for Ill-Health Act. Hugh Arthur Franklin, aged twenty-six years, height 5ft 8ins, sallow complexion, hazel eyes, dark hair, slight dark moustache, of Jewish appearance, wearing pince-nez.

(7) Westerham Herald (17th May 1913)

A house, the Highlands, at Sandgate, near Folkestone, was set fire to during Tuesday night (13th May 1913), and damaged to the extent of £500. An entrance was made by breaking a window at the back, and the staircase was first set alight… Postcards addressed to "The Dishonourable Prime Minister" and "The Dishonourable McKenna" were found, and one was inscribed "Hope this is not a poor widow's house.

(8) The Weekly Dispatch (18th May 1913)

The police are searching for Hugh Arthur Franklin (a nephew of Mr Herbert Samuel, the Postmaster-General) who was sentenced to nine months' imprisonment for setting fire to a train, and who, while in prison, was forcibly-fed over 100 times. He was temporarily released under the powers obtained recently by the Home Secretary, and has failed to return under the conditions of the licence… Three older hunger strikers, Elsie Duval, Phyllis Brady, and Ella Stevenson (alias Ethel Slade), are being similarly sought for.

(9) Grace Cameron Swan, Norwood News (24th May 1913)

You will doubtless recollect that of April 12th the Croydon County Bench saw fit to sentence Miss Elsie Duval and Miss Phyllis Brady, suffragists, to six weeks's imprisonment in the second division on the supposed charge of being "suspected" persons about to commit a felony. During the previous week on remand, they had been treated as convicted prisoners and placed in the third division, contrary to all provisions of the English law, which holds a prisoner to be innocent until legally convicted. With great courage they adopted the hunger strike, and after 17 days of terrible suffering, during which period they were daily subjected to the abominable torture of forcible feeding, they were released in a condition of physical collapse under the "Cat and Mouse Bill".

(10) Staines and Ashford News (2nd September 1999)

Suffragettes set fire to the ground floor of Lady White's house at the junction of Crimp Hill and Ridgemead Road causing £2,000 worth of damage. Two pieces of paper saying "Votes for Women" and "Stop Torturing our Comrades" were left at the scene. One of the suspects, but was released two weeks later as she began a hunger strike.

(11) David Simkin, Family History Research (24th March, 2023)

Victor Diederichs Duval was the second eldest son of Jane Emily Hayes (1860–1924) and Ernest Charles Augustus Diederichs Duval (1858–1953). Victor's father was born Ernest Charles Augustus Diederichs on 13th September 1858 in Mainz, in the Rhineland-Palatinate of Germany to an unmarried woman Emilie/Amelie Diederichs (born 1838, Alsace, France). As a baby, Ernest Diederichs was fostered out to a midwife and her husband, both Roman Catholics..Emilie's brother, Ernst Karl Diederichs, took financial responsibility for her son Ernest and served as his godfather. Ernest Charles Diederichs was baptised as a Protestant. (Ernest's putative father, Eduard Ludwig Schott von Schottenstein was a Lutheran Protestant).

By 1871, Ernest's mother, Emilie/Amelie Diederichs, was residing in London and was employed as a teacher. (At the time of the 1871 Census, Emilie / Amelie Diederichs was recorded as a "Professor of Music and German" and in the 1881 Census she was described as a "Teacher of French"). Between 1858 and 1875, Ernest Diederichs was brought up by his foster parents in Germany. Ernest Diederichs' foster father died in 1873 and his foster mother died in 1874. In 1875, with both his foster parents dead, Ernest Diederichs joined his mother in Battersea, London, but changed his surname to "Duval" so that his unmarried mother was not disgraced and could continue working as a teacher. On the 1881 Census return, Amelie Diederichs and her son Ernest are recorded at 52 Wycliffe Road, Battersea, London. Amelie Diederichs is described as an unmarried "Teacher of French" and her 23-year-old son (under the assumed name of 'Ernest Duval' ) is entered as her "lodger". Ernest Duval gives his occupation as "Correspondence Clerk". Living on the same road as Ernest Duval, at No. 37 Wycliffe Road, Battersea, is 20-year-old "Machinist" Jane Emily Hayes, the daughter of Jane and Thomas Hayes, a "Coachman" in domestic service. Jane Emily Hayes had been born in the Mayfair district of London on 25th November 1860.

On 19th September 1881, at St Mary's Church, Battersea, 23-year-old "Ernest Duval" married 20-year-old Jane Emily Hayes. On the marriage register "Ernest Duval" declared that his father was "Edward Duval, Merchant". Ernest Duval gives his occupation as "Correspondent". Amelie Diederichs (Ernest's mother) is recorded as a witness to the marriage.

The union of 'Ernest Duval' and Jane Emily Hayes produced 9 children:

(1) Ernest Edward Diederichs Duval (1882-1904) who worked as a "Commercial Clerk" before he died from heart disease at the age of 22.

(2) Victor Diederichs Duval (born 16th March 1885, Battersea, Surrey - died 4th October 1945, Queen Victoria Hospital, Morecambe, Lancashire) - see below.

(3) Walter Diederichs Duval (1887-1887). Died 10 days after birth from "Congenital malformation of heart".

(4) Barbara Diederichs Duval (born 11th September 1888, Battersea, Surrey - died 5th January 1919 at South London Hospital for Women, Clapham Common, London).

From the age of 20, Barbara Duval was active in the Women's Suffrage Movement.

1908. Arrested when Muriel Matters chained herself to the grille in the House of Commons. Released on promise to refrain from militancy until age of 21.

1911. Mass window-breaking, and rushing of police cordons. Siblings Elsie Duval and Victor Duval, and her mother, Mrs Jane Emily, also participated.

28 November 1911. Tried for militant suffragist activity at Bow Street Court.

1915. Married Denis Gerald Barry (born circa 1893, Bray, Dublin, Ireland). Served in the British Army during WW1. After the death of his wife, in 1921 emigrated to West Africa.

Marriage produced one child - Denis Francis Doyne Barry (1915–1988).

Death

On 5th January 1919, Barbara Barry (née Duval) died at South London Hospital for Women, Clapham Common, London. Cause of death: Influenza & Lobar Pneumonia. (Spanish 'Flu Epidemic?)(5) Norah Diederichs Duval (born 8th January 1891, Battersea, Surrey, – died 1972, Chipping Norton, Oxfordshire).

1912. Arrested for window smashing. 2nd March 1912, tried for window smashing at Bow Street Court, London. 4 months imprisonment.

20th June 1913. Assisted Lilian Lenton to escape police surveillance. Norah posed as a baker's boy, then changed clothes with Lilian who departed in the van.

16th July 1920 at St John the Evangelist Church, Putney, Norah Duval married Arthur Gerald Benstead (1889–1968), an electrical engineer.

Two sons from marriage - Derek Gerald Benstead (1922–1991) and Arthur Rodney Benstead (born 1926, Kingston, Surrey).6) Elsie Diederichs Duval (born 19th February 1893, Battersea, Surrey - died 1st January 1919, 35 Porchester Terrace, Hyde Park, London)

(7) Winifred Diederichs Duval (born 2nd June 1895, Battersea, Surrey - died 25th April 1918, Ewell Colony, Epsom, Surrey). Cause of death: "Pulmonary Tuberculosis".

(8) Gurney Diederichs Duval (born 27th November 1897, Battersea, Surrey - died some time after 1967). Served in the British Army during WW1. Worked in various jobs - electrical engineer, cafe owner, security officer. Married twice. First marriage dissolved.

(9) Ivy Emily Diederichs Duval (1901–1902). Died in infancy.