Kristallnacht (Crystal Night)

Once in power Adolf Hitler began to openly express anti-Semitic ideas. Based on his readings of how blacks were denied civil rights in the southern states in America, Hitler attempted to make life so unpleasant for Jews in Germany that they would emigrate. The day after the March, 1933, election, stormtroopers hunted down Jews in Berlin and gave them savage beatings. Synagogues were trashed and all over Germany gangs of brownshirts attacked Jews. In the first three months of Hitler rule, over forty Jews were murdered. (1)

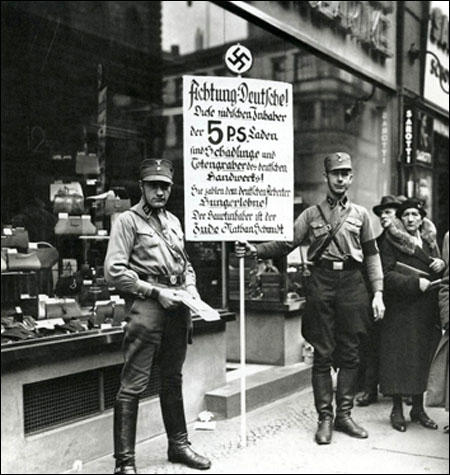

The campaign started on 1st April, 1933, when a one-day boycott of Jewish-owned shops took place. Otto Dibelius, the Bishop of Kurmark stated that he had always been "an anti-semite" and that "one cannot fail to appreciate that in all of the corrosive manifestations of modern civilization Jewry plays a leading role". (2)

Members of the Sturm Abteilung (SA) picketed the shops to ensure the boycott was successful. As a child Christa Wolf watched the SA organize the boycott of Jewish businesses. "A pair of SA men stood outside the door of the Jewish shops, next to the white enamel plate, and prevented anyone who could not prove that he lived in the building from entering and baring his Aryan body before non-Aryan eyes." (3)

Armin Hertz was only nine years old at the time of the boycott. His parents owned a furniture store in Berlin. "After Hitler came to power, there was the boycott in April of that year. I remember that very vividly because I saw the Nazi Party members in their brown uniforms and armbands standing in front of our store with signs: "Kauft nicht bei Juden" (Don't buy from Jews). That of course, was very frightening to us. Nobody entered the shop. As a matter of fact, there was a competitor across the street - she must have been a member of the Nazi Party already by then - who used to come over and chase people away." (4)

the German economy and pay their German employees starvation wages.

The main owner is the Jew Nathan Schmidt.” (1st April, 1933)

Helga Schmidt was only 12 years old when Adolf Hitler came to power. She remembers at school in Dresden that German children were encouraged to hate the Jews. "Certainly there was something of a negative attitude toward the Jews, but before Hitler it did not exist to the same extent. One tolerated them. One let them live. There was never any particular sympathy for the Jews. But to directly label them as our enemies and exploiters, that came from Hitler... and when that has been pounded into people's heads, people will also believe it." However, Helga and her family continued to shop in them "because they were less expensive than other stores." (5)

The hostility towards Jews increased in Nazi Germany. This was reflected in the decision by many shops and restaurants not to serve the Jewish population. Placards saying "Jews not admitted" and "Jews enter this place at their own risk" began to appear all over Germany. In some parts of the country Jews were banned from public parks, swimming-pools and public transport. (6)

Children and Anti-Semitism

The Hitler Youth and the German Girls' League (BDM) played an important role in developing anti-semitism in German schools. Hildegard Koch and her BDM friends began a campaign against the Jewish girls in her class. "The two Jewish girls in our form were racially typical. One was saucy and forward and always knew best about everything. She was ambitious and pushing and had a real Jewish cheek. The other was quiet, cowardly and smarmy and dishonest; she was the other type of Jew, the sly sort. We knew we were right to have nothing to do with either of them. In the end we got what we wanted. We began by chalking Jews out! or Jews perish, Germany awake! on the blackboard before class. Later we openly boycotted them. Of course, they blubbered in their cowardly Jewish way and tried to get sympathy for themselves, but we weren't having any. In the end three other girls and I went to the Headmaster and told him that our Leader would report the matter to the Party authorities unless he removed this stain from the school. The next day the two girls stayed away, which made me very proud of what we had done." (7)

of the propaganda campaign against the Jewish people in Nazi Germany. (c. 1934)

Jewish children in German schools suffered terribly from bullying: "The children called me Judenschwein (Jewish pig)... When I came home I was crying and said, What is a Judenschwein? Who am I? I didn't know who I was. I was only a kid. I didn't know what I was, Jew or not Jew. There were many times when I was beaten up coming from school. I remember one teacher who had something against me because I was a Jew in his class. Every time when I must have been unruly, he used to pull me up front and bend me over and whip me with a bamboo stick." (8)

Josef Stone went to a Jewish school to avoid bullying but he was still targeted by German children while playing in the streets of Frankfurt: "Germans looked at Jews in a sort of bad way.... Children always gave me a hard time. They wouldn't hit me, they just annoyed me with words and yelled obscene things at me. But, at that time, I was too young to even fathom the whole idea. I didn't really get involved until I would say thirteen or fourteen. By that time I started realizing what really was going on, and my parents started to say that eventually we would all have to leave." (9)

Members of the SA put pressure on people not to buy goods produced by Jewish companies. For example, the Ullstein Verlag, the largest publisher of newspapers, books and magazines in Germany, was forced to sell the company to the NSDAP in 1934 after the actions of the SA had made it impossible for them to make a profit. Germans were also encouraged not to use Jewish doctors and lawyers. Jewish civil servants, teachers and those employed by the mass media were sacked. In the 12 months of Hitler taking power, over 40,000 Jewish people left Germany. (10)

Nuremberg Laws

The number of Jews emigrating increased after the passing of the Nuremberg Laws on Citizenship and Race in 1935. The first Reich Law of Citizenship divided people in Germany into two categories. The citizen of "pure German blood" and the rest of the population. The Law for the Protection of German Blood and Honour forbade intermarrying between the two groups. Some 250 decrees followed these laws. These excluded Jews from official positions and professions. They were also forced to wear the "Star of David". (11)

Christa Wolf remembers hearing Joseph Goebbels give a speech on the radio in 1937 about the Jews: "Without fear we may point to the Jew as the motivator, the originator, and the beneficiary of this horrible catastrophe. Behold the enemy of the world, the annihilator of cultures, the parasite among nations, the son of chaos, the incarnation of evil, the ferment of decay, the formative demon of mankind's downfall." She grew up believing that the "Jews are different from us... Jews must be feared, even if one can't hate them." (12)

Adolf Hitler urged Jews to leave Germany. One of the major reasons why so many refused was that they were unable to take their money with them. Hitler arranged for 52,000 to emigrate to Palestine. To encourage them to go the German government allowed "Jews who left for Palestine to transfer a significant portion of their assets there... while those who left for other countries had to leave much of what they owned behind". Richard Evans has argued: "The reasons for the Nazis' favoured treatment of emigrants to Palestine were complex. On the one hand, they regarded the Zionist movement as a significant part of the world Jewish conspiracy they had dedicated their lives to destroying. On the other, helping Jewish emigration to Palestine might mitigate international criticism of anti-semitic measures at home." (13)

As Rita Thalmann and Emmanuel Feinermann, the authors of Crystal Night: 9-10 November 1938 (1974) have pointed out: "After five years of National Socialism, the German government angrily acknowledged that threats and intimidation had not rid the Reich of its Jews. About a quarter of the total had fled but the other three-quarters still preferred to stay in Germany. The government concluded that it would have to change tactics in order to obtain better results." (14)

Kristallnacht (Crystal Night)

On 6th July 1938, a conference of 32 nations met at Evian in France to discuss the growing international problem of Jewish migration. The conference made an attempt to impose general agreed guidelines on accepting Jews from Nazi Germany. According to Richard Evans, the author of The Third Reich in Power (2005): "One delegation after another at the conference made it clear that it would not liberalize its policy towards refugees; if anything, it would tighten things up... Anti-immigrant sentiment in many countries, complete with rhetoric about being 'swamped' by people of 'alien' culture, contributed further to this growing reluctance." (15)

Ernst vom Rath was murdered by Herschel Grynszpan, a young Jewish refugee in Paris on 9th November, 1938. At a meeting of Nazi Party leaders that evening, Joseph Goebbels suggested that there should be "spontaneous" anti-Jewish riots. (16) Reinhard Heydrich sent urgent guidelines to all police headquarters suggesting how they could start these disturbances. He ordered the destruction of all Jewish places of worship in Germany. Heydrich also gave instructions that the police should not interfere with demonstrations and surrounding buildings must not be damaged when burning synagogues. (17)

Heinrich Mueller, head of the Secret Political Police, sent out an order to all regional and local commanders of the state police: "(i) Operations against Jews, in particular against their synagogues will commence very soon throughout Germany. There must be no interference. However, arrangements should be made, in consultation with the General Police, to prevent looting and other excesses. (ii) Any vital archival material that might be in the synagogues must be secured by the fastest possible means. (iii) Preparations must be made for the arrest of from 20,000 to 30,000 Jews within the Reich. In particular, affluent Jews are to be selected. Further directives will be forthcoming during the course of the night. (iv) Should Jews be found in the possession of weapons during the impending operations the most severe measures must be taken. SS Verfuegungstruppen and general SS may be called in for the overall operations. The State Police must under all circumstances maintain control of the operations by taking appropriate measures." (18)

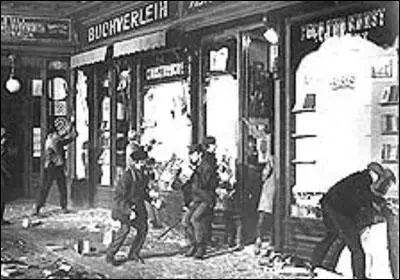

A large number of young people took part in what became known as Kristallnacht (Crystal Night). (19) Erich Dressler was a member of the Hitler Youth in Berlin. "Of course, following the rise of our new ideology, international Jewry was boiling, with rage and it was perhaps not surprising that, in November, 1938, one of them took his vengeance on a counsellor of the German Legation in Paris. The consequence of this foul murder was a wave of indignation in Germany. Jewish shops were boycotted and smashed and the synagogues, the cradles of the infamous Jewish doctrines, went up in flames. These measures were by no means as spontaneous as they appeared. On the night the murder was announced in Berlin I was busy at our headquarters. Although it was very late the entire leadership staff were there in assembly, the Bann Leader and about two dozen others, of all ranks.... I had no idea what it was all about, and was thrilled to learn that were to go into action that very night. Dressed in civilian clothes we were to demolish the Jewish shops in our district for which we had a list supplied by the Gau headquarters of the NSKK, who were also in civilian clothes. We were to concentrate on the shops. Cases of serious resistance on the part of the Jews were to be dealt with by the SA men who would also attend to the synagogues." (20)

Paul Briscoe, the son of Norah Briscoe, a member of the National Union of Fascists, had been educated in Nazi Germany and was living in the small town of Miltenberg: "At first, I thought I was dreaming, but then the rhythmic, rumbling roar that had been growing inside my head became too loud to be contained by sleep. I sat up to break its hold, but the noise got louder still. There was something monstrous outside my bedroom window. I was only eight years old, and I was afraid. It was the sound of voices - shouting, ranting, chanting. I couldn't make out the words, but the hatred in the tone was unmistakable. There was also - and this puzzled me - excitement. For all my fear, I was drawn across the room to the window. I made a crack in the curtains and peered out. Below me, the triangular medieval marketplace had been flooded by a sea of heads, and flames were bobbing and floating between the caps and hats. The mob had come to Miltenberg, carrying firebrands, cudgels and sticks."

Paul Briscoe could hear the crowd chanting "Jews out! Jews out!" In his autobiography, My Friend the Enemy: An English Boy in Nazi Germany (2007) Briscoe recalled: "I didn't understand it. The shop was owned by Mira. Everybody in Miltenberg knew her. Mira wasn't a Jew, she was a person. She was Jewish, yes, but not like the Jews. They were dirty, subhuman, money-grubbing parasites - every schoolboy knew that - but Mira was - well, Mira: a little old woman who was polite and friendly if you spoke to her, but generally kept herself to herself. But the crowd didn't seem to know this: they must be outsiders. Nobody in Miltenberg could possibly have made such a mistake. I was frightened for her.... A crash rang out. Someone had put a brick through her shop window. The top half of the pane hung for a moment, like a jagged guillotine, then fell to the pavement below. The crowd roared its approval." (21)

Armin Hertz was 14 years old in 1938. His parents owned a furniture store in Berlin. He later explained what happened that night: "During the Kristallnacht, our store was destroyed, glass was broken, the synagogues were set on fire. There was a synagogue in the same street where we lived. It was on the first floor of a commercial building; downstairs were stores, and upstairs was a synagogue. In the back of that building, there was a factory so they could not set that synagogue on fire because people were living and working there. But they threw everything out of the window - the Torah scrolls, the prayer books, the benches, everything was lying in the street." (22)

Some people in Germany attempted to help the Jews on Kristallnacht. Susanne von der Borch lived in Munich. She was woken by the sounds of people screaming: "My mother was at the window. I sat up and saw the house opposite in flames. I heard someone screaming, Help! Why doesn't anyone help us? and I asked my mother, Why is the house burning, where are the fire brigades, why are the people screaming? And she just said, Stay in bed." Her mother left the house. "After a longtime, my mother came back. She had fifteen people with her. I was shocked because they were in nightgowns and slippers, or just a light coat. And I could see they were all our Jewish neighbours. She took them into the music room and my brother and I were told, Be quiet and don't move. My mother was very strict, so we didn't move. And we heard our mother phoning people up, and my sister was sent here and there to get drinks for them. Then these people were driven away by our chauffeur to relatives or friends." (23)

Inge Neuberger was an eight-year-old girl who lived in Mannheim. She later recalled that while walking to a Jewish school with her cousin the next morning: "We saw a bonfire in the courtyard in front of the synagogue. Many spectators were watching as prayer books and, I believe, Torah scrolls were burned. The windows had been shattered and furniture had been smashed and added to the pyre. We were absolutely terrified. I am fairly certain that the fire department was in attendance, but no attempt was made to extinguish the flames. We ran back to my home to tell my mother what we had seen. She told us that we would leave the apartment and spend the day in Luisenpark, a very large park in town. We spent the entire day in the park, moving from one area to another." (24)

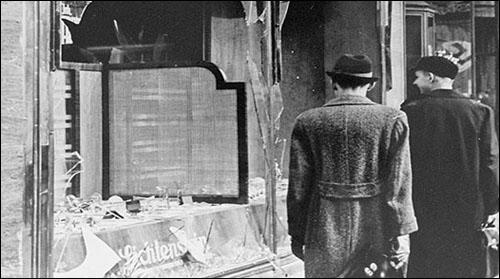

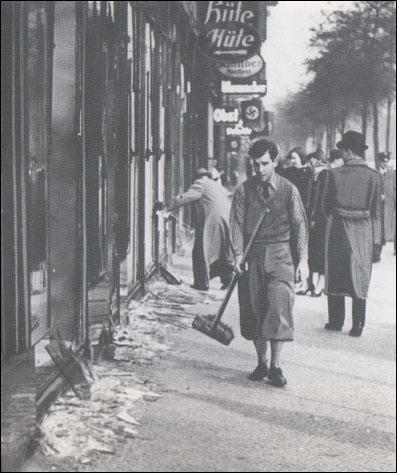

Melita Maschmann was in Berlin that night and "had to pick her way through pieces of broken glass and furniture scattered all over the street". Maschmann asked a policeman what had happened. The policeman’s reply was “In this street they’re almost all Jews.” When he was questioned further he added: “Last night the National Soul boiled over.” She now decided that the "Jews are the enemies of the new Germany. Last night they had a taste of what that means." (25) Despite these comments Maschmann later claimed that, "like many of her upper-middle-class friends, she discounted the violence and anti-semitism of the National Socialist as passing excesses which would soon disappear". (26)

A British journalist, Hugh Carleton Greene, was shocked by what he saw the following morning: "Racial hatred and hysteria seemed to have taken hold of otherwise decent people. I saw fashionably dressed women clapping their hands and screaming with glee while respectable middle-class mothers held up their babies to see the 'fun'. Women who remonstrated with children who were running away with toys looted from a wrecked Jewish shop were spat on and attacked by the mob. There were remarkably few policemen on the streets. Those who were there, when their attention was drawn to the outrages which were proceeding before their eyes, shrugged their shoulders and refused to take any action. Several hundred Jewish shopkeepers were, however, put under 'protective custody' for attempting to shield their property. A state of hopeless panic reigns tonight throughout Jewish circles. Hundreds of Jews have gone into hiding and many businessmen and financial experts of international repute have not dared to sleep in their own homes." (27)

Inge Fehr went to school the next day but was immediately told that she had to return home. "Our headmistress told us a pogrom was in progress. We had to evacuate because members of the Hitler Youth carrying stones were gathering at the front and they were setting other buildings alight. We were all to leave quickly by the back door and not to return to school until further notice. On my way home, I followed the smoke and arrived at the synagogue in the Fasanenstrasse which had been set alight. Crowds were watching from the opposite pavement. I then passed through the Tauentzienstrasse where I saw crowds smashing Jewish shop windows and jeering as the owners tried to salvage their goods. When I got to our house I saw that our chauffeur, who had worked for us for years, had painted Fehr Jude in red paint on the pavement outside." (28)

Armin Hertz was asked my his mother to find out about her sister because she had two little children and in the back of the building where she lived there was also a synagogue. "Get your bicycle and go to Aunt Bertha to see what's going on." Soon after he left home he became aware of the damage that had taken place. "As I was riding along the business district, I saw all the stores destroyed, windows broken, everything lying in the street. They were even going into the stores and running away with the merchandise. Finally, I got to my aunt's house and I saw a large crowd assembled in front of the store. The fire department was there; the police were there. The fire department was pouring water on the adjacent building. The synagogue in the back was on fire, but they were not putting the water on the synagogue. The police were there watching it. I mingled with the crowd. I didn't want to be too obvious. I didn't want to get into trouble. But I heard from people talking that the people who lived there were all evacuated, all safe in the neighborhood with friends. So I went right back and reported to my mother. After Kristallnacht our store was destroyed and it was impossible to stay in Berlin." (29)

Effie Engel was living in Dresden in November 1938. "Just across from us there was a small fabric store that had a Jewish owner. You knew that because of his name. I was still an apprentice at the time of the Kristallnacht, when the Nazis, especially the SA, went around the city destroying all the shops. And those of us in our office were in the immediate vicinity when we watched them smashing up that shop over there across from us. The owner, who was a small, elderly man, and his wife were intimidated and just stood by and wept.... After this the shop was closed. They had stolen everything and cleared it out, and then the two Jews were picked up and they disappeared and never showed up again." (30)

Reinhard Heydrich ordered members of the Gestapo to make arrests following Kristallnacht. "As soon as the course of events during the night permits the release of the officials required, as many Jews in all districts, especially the rich, as can be accommodated in existing prisons are to be arrested. For the time being only healthy male Jews, who are not too old, are to be detained. After the detentions have been carried out the appropriate concentration camps are to be contracted immediately for the prompt accommodation of the Jews in the camps." (31)

Josef Stone was one of those arrested. "Early in the morning I was walking down the street and two SA men came to me and stopped me. 'Come with us,' they said. I didn't know them; they didn't know me, but they must have known I was a Jew. I don't know how they knew, but they knew. They kept me for the rest of the day, but by the evening they let me go. Then, on my way home, I saw all the destruction on the streets." (32) Inge Neuberger remembers her father going into hiding and "spent the next six weeks in the attic of our building. I was given strict orders that if anyone asked about my father's whereabouts I was to say that I didn't know where he was. I remember how strongly this was impressed on me." (33)

Joseph Goebbels wrote an article for the Völkischer Beobachter where he claimed that Kristallnacht was a spontaneous outbreak of feeling: "The outbreak of fury by the people on the night of November 9-10 shows the patience of the German people has now been exhausted. It was neither organized nor prepared but it broke out spontaneously." (34) However, Erich Dressler, who had taken part in the riots, was disappointed by the lack of passion displayed that night: "One thing seriously perturbed me. All these measures had to be ordered from above. There was no sign of healthy indignation or rage amongst the average Germans. It is undoubtedly a commendable German virtue to keep one's feelings under control and not just to hit out as one pleases; but where the guilt of the Jews for this cowardly murder was obvious and proved, the people might well have shown a little more spirit." (35)

On 11th November, 1938, Reinhard Heydrich reported to Hermann Göring, details of the night of terror: "74 Jews killed or seriously injured, 20,000 arrested, 815 shops and 171 homes destroyed, 191 synagogues set on fire; total damage costing 25 million marks, of which over 5 million was for broken glass." (36) It was decided that the "Jews would have to pay for the damage they had provoked. A fine of 1 billion marks was levied for the slaying of Vom Rath, and 6 million marks paid by insurance companies for broken windows was to be given to the state coffers." (37)

David Buffum, the American Consul in Leipzig, reported: "The shattering of shop windows, looting of stores and dwellings of Jews took place in the early hours of 10 November 1938.... In one of the Jewish sections an 18 year-old boy was hurled from a three-story window to land with both legs broken on a street littered with burning beds. The main streets of the city were a positive litter of shattered plate glass. All of the synagogues were irreparably gutted by flames. One of the largest clothing stores was destroyed. No attempts on the part of the fire brigade were made to extinguish the fire. It is extremely difficult to believe, but the owners of the clothing store were actually charged with setting the fire and on that basis were dragged from their beds at 6 a.m. and clapped into prison and many male German Jews have been sent to concentration camps." (38)

The day after Kristallnacht, the Nazi Party held a rally in Nuremberg. Around 100,000 people attended in order to hear the anti-Jewish invective of Julius Streicher, the man known to be the most rabid anti-semite in Nazi Germany. "Photographs of the rally show relatively few men in uniform. Instead, the faces of ordinary Germans - that is, the collective face of Nuremberg and of Germany - can be seen there conveying their ardent support for their government and the eliminationist program." (39)

On the 11th November, 1938, Susanne von der Borch attended a meeting of the German Girls' League: "A few of the Hitler Youth leaders were there, who I normally liked a lot. And they were standing there telling us how they had spent the night. They said they had been at a shop, the Eichengrun in Munich, and they'd smashed the windows, and they'd got hold of one Jew and shaved the hair on his head. And I said, You horrible pigs! And I thought, I have to find out the truth, what was really going on. And that was when I really started to ask serious questions." (40)

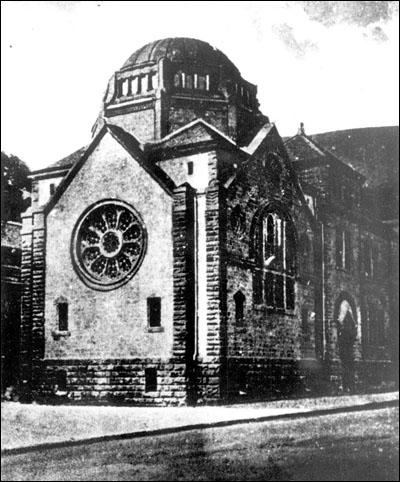

Case Study: Miltenberg Synagogue

On 11th November, 1938, Paul Briscoe was told by his teacher that the day's lessons had been cancelled and that they had to attend a meeting in Miltenberg: "Whatever was going to happen must have been planned well in advance, for the streets were lined with Brownshirts and Party officials, and the boys from the senior school were assembled in the uniform of the Hitler Youth. A festival atmosphere filled the town. Party flags, red, black and white, hung from first-floor windows, fluttering and snapping in the breeze - just as they did during the Führer's birthday celebrations each April. But there was something angry and threatening in the air, too."

The boys were then marched to the Miltenberg Synagogue. "We all stood there staring at it while we waited to find out what was to happen next. For a long moment, nobody moved and all was quiet. Then, another command was shouted - I was too far back to make out the words - and the boys at the front broke ranks, flying at the synagogue entrance, cheering as they ran. When they reached the door, they clambered over each other to beat on it with their fists. I don't know whether they broke the lock or found a key, but suddenly another cheer went up as the door opened and the big boys rushed in. We youngsters stood still and silent, not knowing what to expect."

Herr Göpfert ordered Briscoe and the other young boys to go into the synagogue: "Inside was a scene of hysteria. Some of the seniors were on the balcony, tearing up books and throwing the pages in the air, where they drifted to the ground like leaves sinking through water. A group of them had got hold of a banister rail and kept rocking it back and forth until it broke. When it came away, they flung the spindles at the chandelier that hung over the centre of the room. Clusters of crystal fell to the floor. I stood there, transfixed by shock and disbelief. What they were doing was wrong: why weren't the adults telling them to stop? And then it happened. A book thrown from the balcony landed at my feet. Without thinking, I picked it up and hurled it back. I was no longer an outsider looking on. I joined in, abandoning myself completely to my excitement. We all did. When we had broken all the chairs and benches into pieces, we picked up the pieces and smashed them, too. We cheered as a tall boy kicked the bottom panel of a door to splinters; a moment later, he appeared wearing a shawl and carrying a scroll. He clambered up to the edge of the unbanistered balcony, and began to make howling noises in mockery of Jewish prayers. We added our howls to his."

Briscoe then described what happened next: "As our laughter subsided, we noticed that someone had come in through a side door and was watching us. It was the rabbi: a real, live Jew, just like the ones in our school textbooks. He was an old, small, weak-looking man with a long dark coat and black hat. His beard was black, too, but his face was white with terror. Every eye in the room turned to him. He opened his mouth to speak, but before the words came, the first thrown book had knocked his hat off. We drove him out through the main door where he had to run the gauntlet of the adults outside. Through the frame of the doorway I saw fists and sticks flailing down. It was like watching a film at the cinema, but being in the film at the same time. I caught close ups of several of the faces that made up the mob. They were the faces of men that I saw every Sunday, courteously lifting their hats to each other as they filed into church." (41)

The Miltenberg Synagogue interior was destroyed during Kristallnacht. "A section of the building was later demolished to create space for a parking lot, and the remainder was converted into a residential property. Forty-three Miltenberg Jews emigrated and 42 relocated within Germany. In 1942, the remaining ten Jews were deported to Izbica and to Theresienstadt. At least 39 Miltenberg Jews perished in the Shoah". (42)

Consequences of Kristallnacht

On 12th November, 1938 Joseph Goebbels had a meeting with Hermann Goering and Reinhard Heydrich. Goebbels commented: "I am of the opinion that this is our chance to dissolve the synagogues. All those not completely intact shall be razed by the Jews. The Jews shall pay for it. There in Berlin, the Jews are ready to do that. The synagogues which burned in Berlin are being leveled by the Jews themselves. We shall build parking lots in their places or new buildings. That ought to be the criterion for the whole country, the Jews shall have to remove the damaged or burned synagogues, and shall have to provide us with ready free space. I deem it necessary to issue a decree forbidding the Jews to enter German theaters, movie houses and circuses. I have already issued such a decree under the authority of the law of the chamber for culture. Considering the present situation of the theaters, I believe we can afford that. Our theaters are overcrowded, we have hardly any room. I am of the opinion that it is not possible to have Jews sitting next to Germans in varieties, movies and theaters. One might consider, later on, to let the Jews have one or two movie houses here in Berlin, where they may see Jewish movies. But in German theaters they have no business anymore. Furthermore, I advocate that the Jews be eliminated from all positions in public life in which they may prove to be provocative. It is still possible today that a Jew shares a compartment in a sleeping car with a German. Therefore, we need a decree by the Reich Ministry for Communications stating that separate compartments for Jews shall be available; in cases where compartments are filled up, Jews cannot claim a seat. They shall be given a separate compartment only after all Germans have secured seats. They shall not mix with Germans, and if there is no more room, they shall have to stand in the corridor." (43)

The only people who were punished for the crimes committed on Kristallnacht were members of the Sturm Abteilung (SA) who had raped Jewish women. The judge ruled that this was worse than murder, since they had violated the Nuremberg Laws on sexual intercourse between Aryans and Jews. Such offenders were expelled from the Nazi Party and turned over to the civil courts. The judge released those charged with murder as they were only following orders. (44)

Ulrich von Hassell, a former German diplomat, was appalled by the events of Kristallnacht and the reactions of the major foreign powers: He wrote in his diary: "I am writing under the crushing emotions evoked by the vile persecution of the Jews after the murder of vom Rath. Not since the World War have we lost so much credit in the world, and that shortly after the greatest foreign policy successes. But my chief concern is not with the effects abroad, not with what kind of foreign political reaction we may expect - at least not for the moment. The debility and amnesia of the so-called great democracies is moreover too monstrous. Proof is the signing of the Franco-German Anti-War Agreement at the same time as the furious indignation worldwide against Germany, and the British ministerial visit to Paris. I am most deeply troubled about the effect on our national life which is dominated ever more inexorably by a system capable of such things... There is probably nothing more distasteful in public life than to have to acknowledge that foreigners are justified in criticizing one's own people. As a matter of fact they make a clear distinction between the people and the perpetrators of acts as these. It is futile to deny, however, that the basest instincts have been aroused, and the effect, especially among the young, must have been bad." (45)

Johannes Popitz, the Minister of Finance. had been hostile to Jews in Germany: "As somebody who was very familiar with conditions in the Weimar Republic, my view of the Jewish question was that the Jews ought to disappear from the life of the state and the economy. However, as far as the methods were concerned, I repeatedly advocated a somewhat more gradual approach, particularly in light of diplomatic considerations." (46) This did not stop him criticizing Kristallnacht, Popitz protested the mass persecution of Jews by offering his resignation, which was refused. Although he despised the barbarism of the Nazi Regime, he wanted to see the Reich dominating central and eastern Europe. (47)

However, Emil Nolde, the famous German artist, reacted to Kristallnacht in a much more positive wat. In a letter to a friend he commented that he could “understand” that “the operation for the removal of the Jews, who have burrowed so deep into all peoples” could not be carried out without “a lot of pain”. Not long afterwards, Nolde wrote to the Nazi press chief Otto Dietrich giving his support to Jewish persecution, explaining that he had spent his entire life fighting against the “too-great dominance of Jews in all matters artistic”. (48)

The Jewish community was forced to pay the costs of Kristallnacht: "The Jews were ordered to replace all damaged property, though their insurance - when they had any - was confiscated. At the same time new decrees were issued denying the 500,000 of them a chance to earn a livelihood. They were forbidden to participate in trade or the professions; they were dismissed from all important posts in incorporated companies. Against them as a race was levied a fine of a billion marks, nominally $400 million-roughly half their remaining wealth." (49)

On 21st November, 1938, it was announced in Berlin by the Nazi authorities that 3,767 Jewish retail businesses in the city had either been transferred to "Aryan" control or closed down. Further restrictions on Jews were announced that day. To enforce the rule that Jewish doctors could not treat non-Jews, each Jewish doctor had henceforth to display a blue nameplate with a yellow star - the Star of David - with the sign: "Authorised to give medical treatment only to Jews." German bookmakers were also forbidden to accept bets from Jews. (50)

Joseph Herman Hertz, the Chief Rabbi of Great Britain, asked Sir Michael Bruce, a retired British diplomat, if he could travel to Germany to assess the situation. He was horrified by what he found and went straight to the British Embassy to see Sir Neville Henderson, the British ambassador, who hoped he would contact Lord Halifax, the British foreign secretary, about what could be done to help. "I went at once to the British Embassy. I told Sir George Ogilvie-Forbes everything I knew and urged him to contact Hitler and express Britain's displeasure. He told me he could do nothing. The Ambassador Sir Neville Henderson, was in London and the Foreign Office, acting on instructions from Lord Halifax, had told him to do nothing that might offend Hitler and his minions." (51)

After Kristallnacht the numbers of Jews wishing to leave Germany increased dramatically. The problem was that the world's politicians reacted in a similar way to those dealing with the Syrian refugee crisis. Sweden had taken in a large number of Jewish refugees since 1933. However, the government felt it had taken too many already. According to one source "this attitude was shared by the Jewish minority in Sweden, who were apprehensive that an influx of Jewish refugees might arouse anti-semitic sentiments". (52)

The American Ambassador based in Stockholm reported: "No matter how great the sympathy for the Jews may be in Sweden it is apparent that no one really wants to take the risk of creating a Jewish problem in Sweden also by a liberal admission of Jewish refugees." (53) It was claimed by one Danish newspaper, Politiken, that "Europe is inundated with refugees, but there must certainly be a place for them elsewhere in the world." (54)

Most of the world looked to the United States to take these Jewish refugees. President Franklin D. Roosevelt was approached by Jewish organizations to change the quota system employed by the United States. The combined German and Austrian annual quota of 27,000 was already filled until January 1940. It was suggested that the quotas for the following three years to be combined, allowing 81,000 Jews to enter immediately. (55)

President Roosevelt believed that such a move would not be popular with the American people. A public opinion poll conducted a few months after Kristallnacht asked: "If you were a member of Congress would vote yes or no on a bill to open the doors of the United States to a larger number of European refugees than now admitted under our immigration quotas?" Eighty-three per cent were against such a bill and 8.3 per cent did not know. Of the 8.7 per cent in favour, nearly 70 per cent were Jewish. As the authors of Crystal Night: 9-10 November 1938 (1974) pointed out: "At the very time when sympathy for the victims was at its height, ten Americans out of eleven opposed massive Jewish immigration into the United States." (56)

Secretary of the Interior, Harold Ickes, put forward a plan to settle large numbers of German and Austrian Jewish refuges in the virtually uninhabited 120-mile-long Kenai Peninsula, in Alaska. However, four Alaskan Chambers of Commerce passed resolutions opposing the settlement plan. Felix S. Cohen, one of the Interior Department lawyers, told Ruth Gruber, how Ickes "was determined to help refugees" but that "a whole group of Alaskans came all the way down here just to fight us." These Alaskans "said there was no anti-Semitism in the Territory now because there were only a few Jewish families in each town. Bringing give thousand Jews a year would start race riots." (57)

Philip Noel-Baker, the Labour Party representative for Derby, and a leading Quaker, argued in the House of Commons, that Neville Chamberlain had been morally wrong to make concessions to Hitler and it was time to change policy towards Nazi Germany. He proposed a two-point programme: the threat of reprisals, to halt the arrest and expulsion of the Jews; and the immediate creation of a rehabilitation agency for the hundreds of thousands of emigrants.

"I think they (the Government) might in some measure stay the tyrant's hand in Germany by the means I have suggested. Certainly they can gather the resources, human and material, that are needed to make a new life for this pitiful human wreckage. That wreckage is the result of the mistakes made by all the Governments during the last twenty years. Let the Governments now atone for those mistakes. The refugees have surely endured enough. Dr Goebbels said the other day that he hoped the outside world would soon forget the German Jews. He hopes in vain. His campaign against them will go down in history with St Bartholomew's Eve as a lasting memory of human shame. Let there go with it another memory, the memory of what the other nations did to wipe the shame away." (58)

Chamberlain's rejected Noel-Baker's proposals but did have a meeting with Edouard Daladier, the prime-minister of France on 24th November. Daladier claimed that France had already accepted 40,000 Jewish refugees and urged Britain and the United States to do more. Chamberlain told Daladier that Britain was weekly admitting 500 hundred Jewish refugees: "One of the chief difficulties, however, was the serious danger of arousing anti-semitic feeling in Great Britain. Indeed, a number of Jews had begged His Majesty's Government not to advertise too prominently what was being done." (59)

French newspapers tended to support Daladier. One newspaper argued: "France is a hospitable country. It will not allow a properly accredited diplomat to be assassinated in Paris by a foreign pig who was evading a deportation order... The interests of national defence and of the economy do not permit us to support the foreign elements which have recently installed themselves in and around our capital. Paris has too long been a dumping ground for international hoodlums, the right of asylum must have limits." (60)

The French Socialist Party published a resolution of its executive committee "noting with regret that of all the government of the democratic countries only the French ministers had not thought fit to express publicly their disapproval of the Nazis government's crimes.... The SFIO urges workers to combine forces before the hateful repression embodied in fascism, and to join with the Socialist party in opposing all racial prejudice and in defending the conquests of democracy and the rights of man against adversaries." (61)

The Jewish National Council for Palestine sent a telegram to the British government offering to take 10,000 German children into Palestine. The full cost of bringing the children from Germany and maintaining them in their new homes, as well as their education and vocational training would be paid for by the Palestine Jewish community and by "Zionists throughout the world". (62)

The Colonial Secretary, Malcolm MacDonald, told his Cabinet colleagues that the proposal should be rejected because of a forthcoming conference to be held in London, between the British government and representation of Palestinian Arabs, Palestinian Jews, and the Arab States". He argued that "if these 10,000 children were allowed to enter Palestine, we should run a considerable risk that the Palestinian Arabs would not attend the Conference, and that, if they did attend, their confidence would be shaken and the atmosphere damaged." (63)

Neville Chamberlain was very unsympathetic to the plight of the Jews. He wrote to a friend: "Jews aren't a lovable people; I don't care about them myself." (64) On 8th December, 1938, Stanley Baldwin, a former Prime Minister, made a radio broadcast calling on the British government to do more for the Jews in Nazi Germany. "Thousands of men, women, and children, despoiled of their goods, driven from their homes, are seeking asylum and sanctuary on our doorsteps, a hiding place from the wind and a covert from the tempest... They may not be our fellow subjects, but they are our fellow men. Tonight I plead for the victims who turn to England for help... Thousands of every degree of education, industry, wealth, position, have been made equal in misery. I shall not attempt to depict to you what it means to be scorned and branded and isolated like a leper. The honour of our country is challenged, our Christian charity is challenged, and it is up to us to meet that challenge." (65)

Six days later Chamberlain announced that the government would allow a total of 10,000 Jewish children to enter the country. However, their parents would have to remain in Nazi Germany. He also stated that Jewish refugee organisations in Britain would have to maintain them and would be responsible for finding homes for the children. (66) Anne Lehmann, a twelve-year-old girl from Berlin arrived soon afterwards. She was placed with a non-Jewish couple, Mary and Jim Mansfield, in the village of Swineshead. Anne never saw her parents again as both died at the hands of the Nazis. (67)

A Jewish boy who had witnessed the destruction of the synagogue in the village of Hoengen was another child who was allowed to live in Britain later wrote: "Standing at the window of the train, I was suddenly overcome with a maiming certainty that I would never see my father and mother again. There they stood, lonely, and with the sadness of death... It was the first and last time in my life that I had seen them both weep. Now and then my mother would stretch her hand out, as if to grasp mine - but the hand fell back, knowing it could never reach. Can the world ever justify the pain that burned in my father's eyes?... As the train pulled out of the station to wheel me to safety, I leant my face against the cold glass of the window, and wept bitterly." His parents died in an extermination camp three years later. (68)

In a leading article in Pravda compared the treatment of Jews in Nazi Germany with the pogroms in Tsarist Russia: "The economic difficulties and the discontent of the masses have forced the fascist leaders to resort to a pogrom against the Jews to distract the attention of the masses from grave problems within the country... But anti-semitic pogroms did not save the Tsarist monarchy, and they will not save German fascism from destruction." (69) However, although the Soviet Union was willing to admit communists fleeing from Germany it did nothing to encourage Jewish emigration and rejected requests by the League of Nations High Commissioner for German Refugees to take in people seeking help. (70)

On 9th February, 1939, Senator Robert F. Wagner, introduced a Senate Resolution that would have allowed 20,000 German Jewish refugee children of fourteen and under into the United States. One argument raised against the bill was that the admission of these refugee children "would be against the laws of God, and therefore would open a wedge for a later request for the admission of 40,000 adults - the parents of the children in question". One newspaper claimed that America should concentrate on looking after its own children. Another objection raised was that the bill would create a dangerous precedent that would result in the wholesale breakdown of the existing immigration statutes. The bill "died in committee" and no further action was taken. (71)

An estimated 30,000 Jews were sent to concentration camps after Kristallnacht. (72) Up until this time these camps had been mainly for political prisoners. However, in January 1939, Reinhard Heydrich ordered police authorities all over Germany to release all Jewish concentration camp prisoners who had emigration papers. They were to be told that they would be returned to the camp for life if they ever came back to Germany. (73) Josef Stone later recalled that his father benefited by Heydrich's order as he was released from Dachau after he had obtained permission to emigrate to the United States. "He was away for about four or five weeks... I remember that when he came home, it was late in the evening. I remember when he rang the doorbell he looked strange to us. Although he never had much hair... now he was completely bald." (74)

On 13th May, 1939, the ocean liner, the St Louis, left Hamburg with 927 German Jewish refugees on board. All had immigration quota numbers, issued by the American Consulates in Germany, entitling them to enter the United States. However, this was for the years 1940 and 1941. Henry Morgenthau, Secretary of the Treasury and a Jew, suggested that the refugees be given tourist visas. Cordell Hull, Secretary of State, rejected the idea.

The captain now tried seven Latin American countries - Cuba, Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Panama, Paraguay and Uruguay. All these countries refused to take a single one of these refugees. On 6th June, the liner arrived in Miami and a further request was sent to President Franklin D. Roosevelt. This was ignored and the St Louis returned to Europe. Britain took 288, France 244, Belgium 214 and Holland 181. Those in Britain were safe but more than 200 of those who were given haven by France, Belgium and Holland were killed after being deported to the death camps together with French, Belgian and Dutch Jews. The authors of Voyage of the Damned: A Shocking True Story of Hope, Betrayal, and Nazi Terror (2010) later argued: "What is certain is that if Cuba or the United States had opened their doors, almost no one from the ship need have died." (75)

It has been estimated 115,000 Jews left Germany in the ten months or so between November 1938 and September 1939. It has been calculated that between 1933 and 1939, approximately two-thirds of the Jewish population of Germany left the country. Almost 200,000 had been given refuge in the United States and 65,000 in Britain. Palestine, with all the restrictions imposed on it, accepted 58,000. It is estimated that between 160,000 and 180,000 of those left in Germany died in the concentration camps. (76)

Primary Sources

(1) Reinhard Heydrich, instructions to the Gestapo for measures against Jews (9th November, 1938)

Following the attempt on the life of Secretary of the Legation von Rath in Paris, demonstrations against the Jews are to be expected in all parts of the Reich in the course of the coming night, November 9/10,1938. The instructions below are to be applied in dealing with these events:

I. The chiefs of the State Police, or their deputies, must immediately upon receipt of this telegram contact, by telephone, the political leaders in their areas - Gauleiter or Kreisleiter - who have jurisdiction in their districts and arrange a joint meeting with the inspector or commander of the Order Police to discuss the arrangements for the demonstrations. At these discussions the political leaders will be informed that the German Police has received instructions, detailed below, from the Reichsführer SS and the chief of the German Police, with which the political leadership is requested to coordinate its own measures:

(a) Only such measures are to be taken as do not endanger German lives or property (i.e., synagogues are to be burnt down only where there is no danger of fire in neighboring buildings).

(b) Places of business and apartments belonging to Jews may be destroyed but not looted. The police are instructed to supervise the observance of this order and to arrest looters.

(c) In commercial streets particular care is to be taken that non-Jewish businesses are completely protected against damage.

(d) Foreign citizens - even if they are Jews - are not to be molested.

II. On the assumption that the guidelines are observed, the demonstrations are not to be prevented by the police, who are only to supervise the observance of the guidelines.

III. On receipt of this telegram, police will seize all archives to be found in all synagogues and offices of the Jewish communities so as to prevent their destruction during the demonstrations. This refers only to material of historical value, not to contemporary tax records, etc. The archives are to be handed over to the locally responsible officers of the SD.

IV. The control of the measures of the Security Police concerning the demonstrations against the Jews is vested in the organs of the State Police, unless inspectors of the Security Police have given their own instructions. Officials of the Criminal Police, members of the SD, of the Reserves and the SS in general may be used to carry out the measures taken by the Security Police.

V. As soon as the course of events during the night permits the release of the officials required, as many Jews in all districts, especially the rich, as can be accommodated in existing prisons are to be arrested. For the time being only healthy male Jews, who are not too old, are to be detained. After the detentions have been carried out the appropriate concentration camps are to be contracted immediately for the prompt accommodation of the Jews in the camps. Special care is to be taken that the Jews arrested in accordance with these instructions are not ill-treated.

(2) Heinrich Mueller, head of the Secret Political Police, order sent to all regional and local commanders of the state police (9th November 1938)

(i) Operations against Jews, in particular against their synagogues will commence very soon throughout Germany. There must be no interference. However, arrangements should be made, in consultation with the General Police, to prevent looting and other excesses.

(ii) Any vital archival material that might be in the synagogues must be secured by the fastest possible means.

(iii) Preparations must be made for the arrest of from 20,000 to 30,000 Jews within the Reich. In particular, affluent Jews are to be selected. Further directives will be forthcoming during the course of the night.

(iv) Should Jews be found in the possession of weapons during the impending operations the most severe measures must be taken. SS Verfuegungstruppen and general SS may be called in for the overall operations. The State Police must under all circumstances maintain control of the operations by taking appropriate measures.

(3) Erich Dressler, Nine Lives Under the Nazis (2011)

Of course, following the rise of our new ideology, international Jewry was boiling, with rage and it was perhaps not surprising that, in November, 1938, one of them took his vengeance on a counsellor of the German Legation in Paris. The consequence of this foul murder was a wave of indignation in Germany. Jewish shops were boycotted and smashed and the synagogues, the cradles of the infamous Jewish doctrines, went up in flames.

These measures were by no means as spontaneous as they appeared. On the night the murder was announced in Berlin I was busy at our headquarters. Although it was very late the entire leadership staff were there in assembly, the Bann Leader and about two dozen others, of all ranks.

I was told that an important confidential discussion was in progress. In the corridor the sub-Bann Leader called me and asked how old I was. Then he said: "Well, you're a bit young still, but you'd better come all the same: Come with me."

I had no idea what it was all about, and was thrilled to learn that were to go into action that very night. Dressed in civilian clothes we were to demolish the Jewish shops in our district for which we had a list supplied by the Gau headquarters of the NSKK, who were also in civilian clothes. We were to concentrate on the shops. Cases of serious resistance on the part of the Jews were to be dealt with by the SA men who would also attend to the synagogues.

But there was little resistance. We carried out our orders in competent military fashion. We went in groups of up to twelve men with clubs to break the shop windows. And the night was full of the music of smashed and splintering glass, and the chorus of our Anti Jewish songs "I am a Jew, do you know my nose," and "Ikey Moses has the dough." Only one Jew, the proprietor of a large lingerie store, dared to turn out in his nightgown and start caterwauling; but he didn't stay there long! Or rather, he did stay there but he didn't caterwaul for long.

One thing seriously perturbed me. All these measures had to be ordered from above. There was no sign of healthy indignation or rage amongst the average Germans. It is undoubtedly a commendable German virtue to keep one's feelings under control and not just to hit out as one pleases; but where the guilt of the Jews for this cowardly murder was obvious and proved, the people might well have shown a little more spirit. This should have been a test case, calling for firm and decided action. Nothing of the kind was done. The Jews were let off with a punitive levy; only a few of them were put in a concentration camp, the rest were tamely allowed to emigrate. I felt the whole thing to be rather an unsatisfactory expression of National Socialist ideals.

(4) Paul Briscoe, My Friend the Enemy: An English Boy in Nazi Germany (2007)

At first, I thought I was dreaming, but then the rhythmic, rumbling roar that had been growing inside my head became too loud to be contained by sleep. I sat up to break its hold, but the noise got louder still. There was something monstrous outside my bedroom window. I was only eight years old, and I was afraid.

It was the sound of voices - shouting, ranting, chanting. I couldn't make out the words, but the hatred in the tone was unmistakable. There was also - and this puzzled me - excitement. For all my fear, I was drawn across the room to the window. I made a crack in the curtains and peered out. Below me, the triangular medieval marketplace had been flooded by a sea of heads, and flames were bobbing and floating between the caps and hats. The mob had come to Miltenberg, carrying firebrands, cudgels and sticks.

The rage of the crowd was directed at the small haberdasher's shop on the opposite side of the marketplace. Nobody was looking my way, so I dared to open the window a little, just enough to hear what all the shouting was about.

The words rushed in on the cold, late autumn air. "Ju-den raus! Ju-den raus!" - "Jews out! Jews out!"

I didn't understand it. The shop was owned by Mira. Everybody in Miltenberg knew her. Mira wasn't a Jew, she was

a person. She was Jewish, yes, but not like the Jews. They were dirty, subhuman, money-grubbing parasites - every schoolboy knew that - but Mira was - well, Mira: a little old woman who was polite and friendly if you spoke to her, but generally kept herself to herself. But the crowd didn't seem to know this: they must be outsiders. Nobody in Miltenberg could possibly have made such a mistake. I was frightened for her. The mob was yelling for her to come out, calling her "Jew-girl" and "pig" - "Raus, du Judin, raus, du Schwein!" - but I was willing her to stay put, to hide, to wait for them to go away: No, Mira, don't come out, don't listen to them, please...A crash rang out. Someone had put a brick through her shop window. The top half of the pane hung for a moment, like a jagged guillotine, then fell to the pavement below. The crowd roared its approval, but the roar subsided as people began to nudge and point. Three storeys above them, a window was opened, and a pale, frightened face looked out. The window was level with mine, and I could see Mira very clearly. Her eyes were dark, like glistening currants.

The mob fell silent to let her speak, and her thin voice trembled over their heads. "Was ist los? Warum all das?" - "What's going on? What's all this about?" But it was clear that she knew. A man in the crowd mimicked her in mocking falsetto, and the Marktplatz echoed with cruel laughter. Another voice yelled, "Raus, raus, raus!" and the cry was picked up and quickly became a chant. The call was irresistible. Soon, Mira was standing in the wrecked doorway of her shop, among the ribbons, reels and rolls of cloth that lay scattered among the broken glass. She was wearing a long white nightdress. The wind caught it, and it ballooned about her. Then she was gone, lost in the crowd, which moved off along the Hauptstrasse towards the middle of the town. Behind them, the marketplace filled with dark. Hugh Carleton Greene

(5) Hugh Carleton Greene, The Daily Telegraph (12th November, 1938)

On the Kurfürstendamm, the interior of every Jewish shop was systematically demolished by youths armed with hammers, brooms and lengths of lead piping. In Dobrin, a fashionable Jewish cafe, the mob smashed the counter and the table and chairs and then stamped cream cakes and confectionery into the floor. Weisz Czarda, a restaurant owned by a Hungarian Jew, was invaded by another horde which cast chairs and tables out on to the street...

Racial hatred and hysteria seemed to have taken hold of otherwise decent people. I saw fashionably dressed women clapping their hands and screaming with glee while respectable middle-class mothers held up their babies to see the "fun". Women who remonstrated with children who were running away with toys looted from a wrecked Jewish shop were spat on and attacked by the mob.

There were remarkably few policemen on the streets. Those who were there, when their attention was drawn to the outrages which were proceeding before their eyes, shrugged their shoulders and refused to take any action. Several hundred Jewish shopkeepers were, however, put under "protective custody" for attempting to shield their property. A state of hopeless panic reigns tonight throughout Jewish circles. Hundreds of Jews have gone into hiding and many businessmen and financial experts of international repute have not dared to sleep in their own homes.

(6) Joseph Goebbels, article in the Völkischer Beobachter (12th November, 1938)

The outbreak of fury by the people on the night of November 9-10 shows the patience of the German people has now been exhausted. It was neither organized nor prepared but it broke out spontaneously.

(7) Yitzbak S. Herz worked at Dinslaken Orphanage in 1938. He managed to escape to Australia where he wrote about what happened during Crystal Night.

Early one morning I was awakened by the shrill ringing of the door bell. With a sense of foreboding I opened the front door. Three men, two Gestapo officers and a policeman in mufti, entered announcing: "This is a police raid! We are looking for arms in all Jewish homes and apartments and so we shall search the orphanage too!" The three commenced their task at once. They searched only the ground floor, especially the small office and the children's workroom. In the office they cut the telephone wires and, searching for money, opened the lockers and drawers of the young students. Unobserved for a moment, the Gestapo officer Schneider whispered in my ear: "During the night all the Jewish men in Dinslaken were arrested. But there is no need for you to worry. Nothing will happen to you! You will remain in charge of the children." Schneider, I later found out, was a former Social Democrat and had always been friendly to Jews. After the search which lasted for twenty-five minutes and which - as was to be expected - yielded no tangible results, the Nazi officers left the building and gave the following order: "Nobody is to leave the house before 10 a.m. All the blinds of the building facing the street must be drawn! Shortly after 10 a.m. everything will be over!"

About one hour later, at 7 a.m., the morning service in the synagogue of the institution was scheduled to commence. Some people from the town usually participated, but this time nobody turned up. Only the teacher of the Jewish primary school and two Polish Jews, who escaped during the Polish action of October, attended the minyan. Then I heard the ringing of the house bell. The sound of the bell, which I hastened to answer, became louder and louder. When I opened the door a strange man faced me. In the dim light of the street lamp I recognized a Jewish face. In a few words the stranger explained to me: "I am the president of the Jewish community of Dusseldorf. I spent the night in the waiting room of the Gelsenkirchen railway station. I have only one request-let me take refuge in the orphanage for a short while. While I was traveling to Dinslaken I heard in the train that anti-Semitic riots had broken out everywhere, and that many Jews had been arrested. Synagogues everywhere are burning!"

With anxiety I listened to the man's story; suddenly he said with a trembling voice: "No, I won't come in! I can't be safe in your house! We are all lost!" With these words he disappeared into the dark fog which cast a veil over the morning. I never saw him again. In spite of this Job's message I forced myself not to show any sign of emotion. Only thus could I avoid a state of panic among the children and tutors. Nonetheless I was of the opinion that the young students should be prepared to brave the storm of the approaching catastrophe. About 7.30 a.m. I ordered forty-six people - among them thirty-two children - into the dining hall of the institution and told them the following in a simple and brief address:

"As you know, last night a Herr von Rath, a member of the German embassy in Paris, was assassinated. The Jews are held responsible for this murder. The tension in the political field is now being directed against the Jews, and during the next few hours there will certainly be anti-Semitic excesses. This will happen even in our town. It is my feeling and my impression that we German Jews have never experienced such calamities since the Middle Ages. Be strong! Trust in God! I am sure we will withstand even these hard times. Nobody will remain in the rooms of the upper floor of the building. The exit door to the street will be opened only by myself From this moment on everyone is to heed my orders only!"

(8) Armin Hertz, was fourteen years old in 1938. He was interviewed by the authors of What We Knew: Terror, Mass Murder and Everyday Life in Nazi Germany (2005)

During the Kristallnacht, our store was destroyed, glass was broken, the synagogues were set on fire. There was a synagogue in the same street where we lived. It was on the first floor of a commercial building; downstairs were stores, and upstairs was a synagogue. In the back of that building, there was a factory so they could not set that synagogue on fire because people were living and working there. But they threw everything out of the window-the Torah scrolls, the prayer books, the benches, everything was lying in the street.

My mother was very worried about her sister, because she had two little children and in the back of the building where she lived there was also a synagogue. So we tried to get in touch with her by phone the next day, but nobody answered. My mother got desperate and said to me, "Get your bicycle and go to Aunt Bertha to see what's going on." As I was riding along the business district, I saw all the stores destroyed, windows broken, everything lying in the street. They were even going into the stores and running away with the merchandise. Finally, I got to my aunt's house and I saw a large crowd assembled in front of the store. The fire department was there; the police were there. The fire department was pouring water on the adjacent building. The synagogue in the back was on fire, but they were not putting the water on the synagogue. The police were there watching it. I mingled with the crowd. I didn't want to be too obvious. I didn't want to get into trouble. But I heard from people talking that the people who lived there were all evacuated, all safe in the neighborhood with friends. So I went right back and reported to my mother. After Kristallnacht our store was destroyed and it was impossible to stay in Berlin.

(9) Susanne von der Borch was fifteen years old in 1938. She was interviewed by Cate Haste, for her book, Nazi Women (2001)

My mother was at the window. I sat up and saw the house opposite in flames. I heard someone screaming, "Help! Why doesn't anyone help us?" and I asked my mother, "Why is the house burning, where are the fire brigades, why are the people screaming?" And she just said, "Stay in bed."

And she left the house with my older sister. I woke up my younger brother who was two years younger. And we sat on the stairs and waited for a long time. It was very ghostly, because we heard these screams and saw the flames.

After a longtime, my mother came back. She had fifteen people with her. I was shocked because they were in nightgowns and slippers, or just a light coat. And I could see they were all our Jewish neighbours. She took them into the music room and my brother and I were told, "Be quiet and don't move."

My mother was very strict, so we didn't move. And we heard our mother phoning people up, and my sister was sent here and there to get drinks for them. Then these people were driven away by our chauffeur to relatives or friends.

And my mother told us afterwards that one of her neighbours, Frau Bach, was standing in front of her house without shoes in her nightgown, and my mother had a pile of coats and shoes and things, but Frau Bach said to her, "Well, at least I have my husband." And at that moment a car arrived with the SA, and they took Herr Bach into the car and he was driven to Dachau. But he was freed after a few weeks. He came back and they escaped to England, then America.

It was a shocking experience for me, and it did make me think more about the whole movement...

At a meeting the following day... a few of the Hitler Youth leaders were there, who I normally liked a lot. And they were standing there telling us how they had spent the night. They said they had been at a shop, the Eichengrun in Munich, and they'd smashed the windows, and they'd got hold of one Jew and shaved the hair on his head. And I said, "You horrible pigs!" And I thought, I have to find out the truth, what was really going on. And that was when I really started to ask serious questions.

(10) Effie Engel was interviewed by the authors of the book, What We Knew: Terror, Mass Murder and Everyday Life in Nazi Germany (2005)

Just across from us there was a small fabric store that had a Jewish owner. You knew that because of his name. I was still an apprentice at the time of the Kristallnacht, when the Nazis, especially the SA, went around the city destroying all the shops. And those of us in our office were in the immediate vicinity when we watched them smashing up that shop over there across from us. The owner, who was a small, elderly man, and his wife were intimidated and just stood by and wept.

One of my colleagues and I then said to our boss, who was a Nazi, "Well, Herr Klose, do you think this is right? We think it's outrageous." We basically put him under a bit of pressure. And then he said, "I can't approve of that either." Even he thought that things had gone too far.

After this the shop was closed. They had stolen everything and cleared it out, and then the two Jews were picked up and they disappeared and never showed up again. I didn't know them personally. I only knew them by sight.

(11) Josef Stone was interviewed by the authors of the book, What We Knew: Terror, Mass Murder and Everyday Life in Nazi Germany (2005)

I remember on November 10, 1938, at the Kristallnacht, that I didn't know anything about it that morning. Early in the morning I was walking down the street and two SA men came to me and stopped me. "Come with us," they said. I didn't know them; they didn't know me, but they must have known I was a Jew. I don't know how they knew, but they knew...

They lined them up and just said, "Stand there." Nobody said anything. Nobody did anything. They didn't give us food or anything. We just stood there for the whole day. And I'm sure the others stood there longer. But by late evening or early evening, I don't remember the time, they called me and asked, "How old are you?" At that time in 1938, I was sixteen and I was able to get out and go home. And that was that...

I never got hit. At first when they combed the street, they took us to some sort of assembly point where they already had another twenty, thirty, or forty people. I don't remember exactly how many they marched there. It really wasn't that far away. While we walked there, and, of course, after the walk, all the people on the sidewalks started yelling at us-normal Germans, children and adults, and women also. There were no exceptions: man, woman, and child. They knew who we were because they walked us down as a group of forty or fifty people [and because those who marched us] wore uniforms, SA uniforms. The people just walking down the streets who saw us coming just let loose with insults. Maybe they were told that we were marching through the streets and that they should just yell at us. But I don't know, it could have been spontaneous. But who can tell?

My father was arrested a couple of days later and taken to Dachau. While he was away, I went to the American consulate in Stuttgart and checked out our papers and I was assured at that time that our number, our registration number, would be called in early 1939. With that information, and with the fact that my father was a Frontkdmpfer [frontline soldier] from World War I, I went to the police and gave them all the information, and they said that on that basis he would be released shortly. It still took a couple of weeks. I imagine that he was away for about four or five weeks and then he came home. While we were in Germany, my father never spoke about it. He never said a word. He said, "I'm not talking about it. It's forgotten now." But look, we were all glad. Once he came home, we made our entire efforts to get out, to get rid of our things, and to make sure that our relatives who lived in a small town in Warttemberg could take over our apartment. We left the furniture; we left everything for them to take over. We left it for them because they had nothing. They had smashed their furniture and what not. But that was a small town - everybody knew everyone. They moved in there as we moved out.

(12) Inge Neuberger, letter to Martin Gilbert about the reasons why her family decided to leave Germany (15th June, 2005)

My family, which consisted of my father, mother, my maternal grandmother, my older brother, and I were eating dinner (on 9th November, 1938) when there was a knock at our front door. I can still picture my father's somewhat ruddy complexion turning white, and the quizzical look that passed between my parents. My mother said she would answer the door, and I went with her. There stood a German woman who worked in our home as part-time housekeeper. When my mother asked her what she was doing there, she answered that my father had to leave the house the next day. I recall her saying that something was going to happen, although she did not know what. And she left as quickly and quietly as she had come....

The next morning... I met my cousin and we walked to school together. I remember that it was a relatively long walk, and as Jews we could not ride the trolley car. We walked along a broad, pedestrian street and came upon an 'army' of men marching four or more abreast. They wore no uniforms but were dressed as working men would have been. Each had a household tool over his shoulder. I remember seeing rakes, shovels, pickaxes, etc., but no guns. My cousin and I were puzzled by this parade, and watched for some minutes. Then we continued on to school.

We saw a bonfire in the courtyard in front of the synagogue. Many spectators were watching as prayer books and, I believe, Torah scrolls were burned. The windows had been shattered and furniture had been smashed and added to the pyre. We were absolutely terrified. I am fairly certain that the fire department was in attendance, but no attempt was made to extinguish the flames. We ran back to my home to tell my mother what we had seen. She told us that we would leave the apartment and spend the day in Luisenpark, a very large park in town. We spent the entire day in the park, moving from one area to another.

(13) Inge Fehr, letter to Michael Smith (2nd April, 1997)

Our headmistress told us a pogrom was in progress. We had to evacuate because members of the Hitler Youth carrying stones were gathering at the front and they were setting other buildings alight. We were all to leave quickly by the back door and not to return to school until further notice.

On my way home, I followed the smoke and arrived at the synagogue in the Fasanenstrasse which had been set alight. Crowds were watching from the opposite pavement. I then passed through the Tauentzienstrasse where I saw crowds smashing Jewish shop windows and jeering as the owners tried to salvage their goods. When I got to our house I saw that our chauffeur, who had worked for us for ca years, had painted Fehr Jude in red paint on the pavement outside.

(14) David Buffum, American Consul in Leipzig (November, 1938)

The shattering of shop windows, looting of stores and dwellings of Jews took place in the early hours of 10 November 1938, and was hailed in the Nazi press as a "spontaneous wave of righteous indignation throughout Germany, as a result of the cowardly Jewish murder of Third Secretary von Rath in the German Embassy in Paris." So far as a very high percentage of the German populace is concerned, a state of popular indignation that would spontaneously lead to such excesses, can be considered non-existent. On the contrary, in viewing the ruins all of the local crowds observed were obviously benumbed over what had happened and aghast over the unprecedented fury of Nazi acts that had been or were taking place with bewildering rapidity.

In one of the Jewish sections an 18 year-old boy was hurled from a three-story window to land with both legs broken on a street littered with burning beds. The main streets of the city were a positive litter of shattered plate glass. All of the synagogues were irreparably gutted by flames. One of the largest clothing stores was destroyed. No attempts on the part of the fire brigade were made to extinguish the free. It is extremely difficult to believe, but the owners of the clothing store were actually charged with setting the fire and on that basis were dragged from their beds at 6 a.m. and clapped into prison and many male German Jews have been sent to concentration camps.

(15) Paul Briscoe, My Friend the Enemy: An English Boy in Nazi Germany (2007)

Whatever was going to happen must have been planned well in advance, for the streets were lined with Brownshirts and Party officials, and the boys from the senior school were assembled in the uniform of the Hitler Youth. A festival atmosphere filled the town. Party flags, red, black and white, hung from first-floor windows, fluttering and snapping in the breeze - just as they did during the Führer's birthday celebrations each April. But there was something angry and threatening in the air, too...

Herr Göpfert was swaggering and grinning, strolling along beside us, hands on hips, chest pushed out. He looked like a uniformed toad. We were still struggling to get our short legs to fall in with the pace of the seniors when the whole column was suddenly called to a halt.