Emil Nolde

Emil Nolde was born as Emil Hansen, near the village of Nolde, Germany, on 7th August, 1867. His parents, devout Protestants, were peasants. "Of Danish-German lineage, he was part of an ethnic minority that opted for life in the German Reich even under foreign citizenship. He became a carver and draftsman and in 1892 began creating watercolours of mountain motifis in Switzerland." (1)

In 1892 he became a drawing instructor at the Museum of Industrial and Applied Arts. His main objective was to become a full-time artist but it was not until 1905 that he had his first art exhibition. The following year he briefly joined with Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Max Pechstein, Fritz Bleyl, Karl Schmidt-Rottluff and Erich Heckel to form Die Brücke, the first group of German Expressionist painters. Kirchner and his friends were all in their early to mid-20s, determined, they said, "to wrest freedom for our actions and our lives from the older, comfortably established forces." (2)

Emil Nolde and German Expressionism

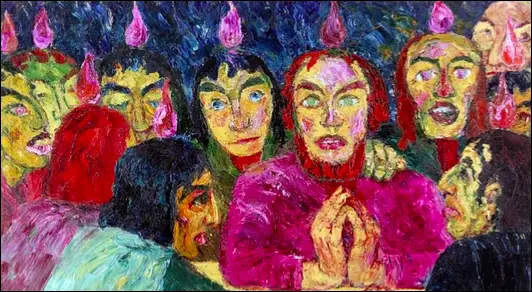

Nolde's held anti-Semitic views and this was expressed in the Pentecost (1909). However, the painting was rejected for an exhibition by the Berlin Secession, an artist group founded in 1898 in opposition to European salons and as a defender of traditional German culture. "Nolde was deeply attached to the work depicting the visitation of the Holy Spirit upon Jesus Christ’s apostles after their savior’s death and resurrection". After its rejection Nolde wrote a scathing letter to Berlin Secession president Max Liebermann. The letter was leaked to the press and Nolde never forgave Liebermann, a Jewish German, and accused him of subverting true German culture. "Throughout his life Nolde suffered from negative art-criticism and in this anti-Semitic conspiracy theory he found something it could be convincingly attributed to.” (3)

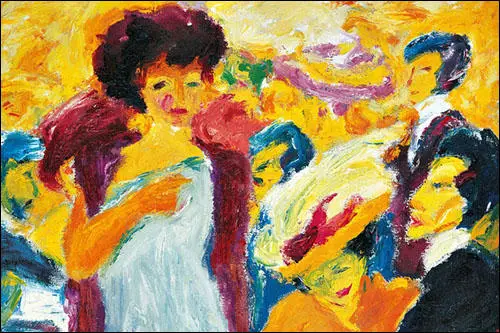

An example of Nolde's expressionism can be seen in The Party (1911). "It is a gathering of cold-eyed strangers with yellow faces. Sex hums through the bright light but so does menace." (4) Nolde's wife, Ada Vilstrup worked as a dancer. "Its louche characters and hubbub inspired vivid graphics, stage-lit in watercolour." Nolde was at the forefront of "a generation of German artists who eschewed saccharine Impressionism for a new, emotionally charged vocabulary. His debt to both his forebears and contemporaries is evident: the harrowing realism of Grünewald rubs shoulders with the heartfelt, early depictions of peasants by Nolde’s great hero Van Gogh; haunted, Ensor-like masks jostle with something like the gaiety of Toulouse-Lautrec." (5)

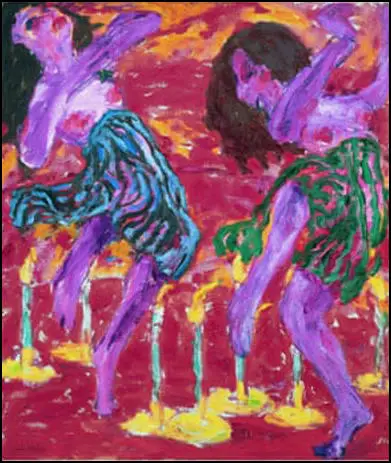

The following year he painted The Candle Dancers (1912). According to Jonathan Jones: "It is the German answer to Matisse’s Dance. It is a lot more chaotic and frenzied, a confession of lust and intoxication. Two women wearing nothing but translucent skirts are throwing their limbs about wildly as they jump between lighted candles. Nolde juxtaposes their purple-pink flesh with a red and gold background like the fires of hell.... Yet this erotic reverie is fraught, uneasy. Nolde, who grew up in farm country and regularly returned there to paint, finds pre-first world war Berlin a corrupt, scary place." (6)

Nolde held anti-Semite views and in a letter sent to a friend in 1911 drew a distinction between “Jews” and “Germans” and claimed that the leaders of the Berlin Secession art movement, such as Max Liebermann, Lovis Corinth and Max Pechstein, were Jews. He added that “the art dealers are all Jews”, as were the “leading art critics” and that “the entire press was at their disposal”. He went on to make the allegation that the Secession movement was spreading like “dry rot” throughout the country. (7)

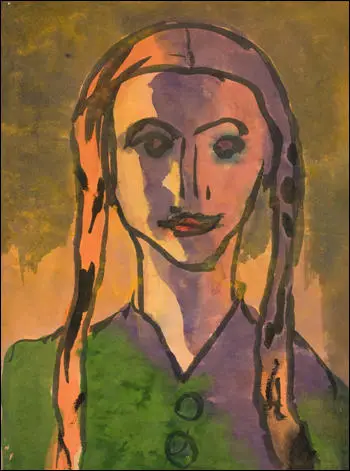

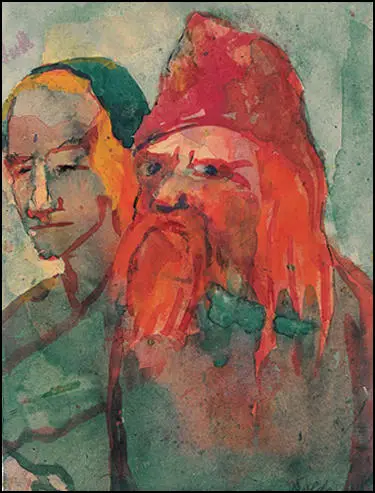

Nolde became known for his harsh, almost grotesque depictions of biblical scenes. In 1921 Emil Nolde painted Paradise Lost. It was highly controversial but it had its supporters. Calvin Seerveld has argued: "The oil painting catches in vivid, sensuous colour the aftermath of the fall into sin by the disobedient action of Eve and Adam. The yellow, orange-haired Eve stares out at us unseeing, listless and disconsolate. Bearded Adam is grim, faced with the long haul of hard labour ahead of him on a cursed brown earth. The serpent curled around a tree, beady-eyed with fang hanging out, separates the disgruntled pair. A saber-toothed lion presses forward out of the background (left), while a couple of red flowers and trees (right) hint at the garden of Eden left behind. Nolde depicts the rough loneliness and tiresome petulence that are the wages of sin for us elemental, agitated humans, world with an end." (8)

Jonathan Jones claims that Nolde's anti-Semitism can be seen in his paintings: "Looking at the alien, weirdly coloured faces that populate Nolde’s nightmare world, I start to see features that are troubling not aesthetically but historically. Does one of the men in his 1908 painting Market People have a hooked nose straight out of antisemitic caricature? And are the theatre-going couple in 1911’s In the Box being similarly reduced to antisemitic stereotypes? I wonder if I am overreacting, as the gallery labels appear blithely unaware. Then finally in front of Nolde’s 1921 triptych Martrydom there is no room for doubt. As Christ suffers on the cross, two monstrously caricatured Jewish witnesses gloat in the foreground. This is a modernist version of a very ancient hate." (9)

Anti-Semitism

Nolde was strongly opposed to the Russian Revolution and saw it as part of a Jewish conspiracy. In 1931 he wrote that “the whole Soviet system was of Jewish origin and served Jewish interests”, which were to use “the power of money” to gain “world domination”. (10) He supported Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party and on 9th November, 1933, attended a dinner commemorating the 10th anniversary of the Beer Hall Putsch, the failed coup in which Nazis attempted to seize power from the Bavarian government. “The Führer is great and noble in his aspirations and a genius man of action” Nolde wrote in a letter to a friend the following day. He also raised concerns that Hitler “is still being surrounded by a swarm of dark figures in an artificially created cultural fog.” The “dark figures” to which he referred were Jewish Germans who, the artist believed, sought to destroy what he considered “pure” German art through cultural diversity. (11)

Barry Schwabsky has tried to explain Nolde's Anti-Semitism: "Nolde’s psychology will sound familiar to anyone who has ever spent much time around artists. There’s a certain significant minority among them whose arrogant certainty that they have never been properly recognized - and somehow no amount of recognition may ever be quite enough - tends to devolve into fantasies of persecution, the feeling that some cabal or mafia is arrayed against them. For Nolde, this was the Jews. In another time and place, this obsession might have remained a private affair, known only to a few intimates, but Nolde had the moral bad luck to be a contemporary of the Nazis, of whom he became an early and avid supporter." (12)

Nolde was determined to enter Hitler’s good graces. A year after meeting him at the dinner party, he wrote an autobiography modeled on Hitler’s Mein Kampf entitled Jahre der Kämpfe (or Years of Struggle, using the plural of “Kampf”). In the book he advocated eugenics: “Some people, particularly the ones who are mixed, have the urgent wish that everything - humans, art, culture - could be integrated, in which case human society across the globe would consist of mutts, bastards and mulattos.” (13)

Nolde welcomed the action that Hitler took against the Jews. He not only denounced his fellow artist Max Pechstein as a “Jew” (he wasn’t), but in the summer of 1933 drafted a plan for how to remove Jews from German society. At the time several leading Nazis, including Joseph Goebbels and Albert Speer had paintings by Nolde on their walls. Goebbels, the head of the Culture Ministry, served as a honorary patron of an exhibition on Italian Futurism in Berlin in March, 1934. (14) In a speech made in June 1934, Goebbels argued "We National Socialists are not un-modern; we are the carrier of a new modernity, not only in politics and in social matters, but also in art and intellectual matters." (15)

Goebbels was in a minority and Paul Schultze-Naumburg, a senior figure in the Nazi Party, wrote a pamphlet entitled, The Struggle for Art: (1932) attacking the knd of modern art being produced by people like Nolde. "Woman has probably never been depicted so disrespectfully and in so unappetizing a way as in the paintings we have been obliged to put up with in German exhibits of the last twelve years, paintings that inspire only nausea and distrust. They convey not the slightest trace of the sacredness of the human body or of the glory of a divine nakedness. They express a ravening lasciviousness that sees the nude only as an undressed human being in its lowest form... The essential element of art, as we understand it, is therefore to always show a ‘spiritual direction’. And the idea of National Socialism is based on appropriately 'giving direction' to the German people and leading it to salvation. And since that task is substantially conducted with spiritual tools, national socialism cannot ignore the instrument of art." (16)

Alois Schardt, a member of the Nazi Party and one of the directors at the Berlin National Art Gallery, was a defender of the work of Emile Node. He saw the Expressionist struggle as a spiritual renewal and as a return to the Germanic heritage. In his lecture, What is German Art? Schardt presented his theoretical justification for his position. He argued there was a direct link between the nonobjective ornamentation of the German bronze age and Expressionist painting. "The decline of German art began in 1431 when naturalism began to impringe on expressive art. Everything created after the first century in Germany was of only historical and documentary value and was essentially un-German." (17)

Nolde did not paint in "the hyper-realistic style that Hitler preferred, favoring instead bold brushstrokes and electrifying colors to evoke visceral feelings of primal passion." (18) Hitler hated Emil Nolde's work commenting: "Whatever he paints are nevertheless always piles of manure.” (19). In the same year as he took power, the Führer repeatedly described Nolde as a “pig” and swore that he would not spend a penny of the new regime’s money on giving him commissions. Hitler also announced that gallery directors would be instructed not to buy any more of his works on pain of imprisonment. (20)

When Hitler gained power he appointed Adolf Ziegler, a strong supporter of Schultze-Naumburg, as his artistic adviser. In November, 1933, Schardt was dismissed from office. In January 1934 Hitler had appointed Alfred Rosenberg as the cultural and educational leader of the Reich. Ziegler got support from Rosenberg in his disagreement with Goebbels. Rosenberg saw his mission to preserve the "folkish ideology in its purest form" and rejected Goebbels's belief that artists such as Heckel, Nolde and Barlach were representative of contemporary Germany's "indigenous Nordic" art. (21)

Hitler was asked to intervene in the dispute. He made his position clear in a speech in September, 1934. Hitler argued that there were "two dangers" that National Socialism had to overcome. First, the iconoclastic "saboteurs of art," were threatening the development of art in Nazi Germany. "These charlatans are mistaken if they think that the creators of the new Reich are stupid enough or insecure enough to be confused, let alone intimidated, by their twaddle. They will see that the commissioning of what may be the greatest cultural and artistic projects of all time will pass them by as if they had never existed." (22)

Art and Fascism

In 1936 Adolf Ziegler became President of the Reich Chamber of Fine Arts (Reichskammer der bildenden Kuenste), a subdivision of the Cultural Ministry under Joseph Goebbels. (23) Ziegler made all artists join the Reich Chamber of Fine Arts. In this way it became possible to prevent artists who were opposed to the policies of the Nazi government from working. For example, Otto Dix had to promise to paint only inoffensive landscapes or portraits. However, he was eventually sacked as professor at the Dresden School of Arts and Crafts. Dix's dismissal letter said that his work "threatened to sap the will of the German people to defend themselves." (24)

In June 1936, Joseph Goebbels wrote in his diary: "Horrible examples of art Bolshevism have been brought to my attention... I want to arrange an exhibit in Berlin of art from the period of degeneracy. So that people can see and learn to recognize it." (25) By the end of the month he had obtained Hitler's permission to requisition "German degenerate art since 1910" from public collections for the show. Goebbels actually liked modern art and was a collector of the work of Emil Nolde. As Richard J. Evans has pointed out: "Its political opportunism was cynical even by Goebbels's standards. He knew that Hitler's hatred of artistic modernism was unquestionable, and so he decided to gain favour by pandering to it, even though he did not share it himself." (26)

On 27th November, 1936, Goebbels issued the following decree: "On the express authority of the Führer, I hereby empower the President of the Reich Chamber of Visual Arts, Professor Ziegler of Munich, to select and secure for an exhibition works of German degenerate art since 1910, both painting and sculpture, which are now in collections owned by the German Reich, by provinces, and by municipalities. You are requested to give Professor Ziegler your full support during his examination and selection of these works." (27)

Ziegler and his entourage toured German galleries and museums and picked out works to be taken to the new exhibition, some museum directors were furious, refused to co-operate, and pleaded with Hitler to obtain compensation if the the confiscated works were sold abroad. Such resistance was not tolerated and some of them lost their jobs. Over a 100 works were seized from the Munich collections, and comparable numbers from museums elsewhere. (28)

The Degenerate Art Exhibition

The Degenerate Art Exhibition organized by Adolf Ziegler and the Nazi Party in Munich took place between 19th July to 30th November 1937. The exhibition presented 650 works of art, confiscated from German museums. This included 27 of Nolde’s paintings, watercolors, and etchings. (29) The day before the exhibition started, Hitler delivered a speech declaring "merciless war" on cultural disintegration. Degenerate art was defined as works that "insult German feeling, or destroy or confuse natural form or simply reveal an absence of adequate manual and artistic skill". Whereas these artists are "men who are nearer to animals than to humans, children who, if they lived so, would virtually have to be regarded as curses of God." (30)

Ziegler made a speech at the opening of the exhibition. "Our patience with all those who have not been able to fall in line with National Socialist reconstructions during the last four years is at an end. The German people will judge them. We are not scared. The people trust, as in all things, the judgment of one man, our Führer. He knows which way German art must go in order to fulfil its task as the expression of German character... What you are seeing here are the crippled products of madness, impertinence, and lack of talent... I would need several freight trains clear our galleries of this rubbish... This will happen soon." (31)

The exhibition included paintings, sculptures and prints by 112 artists. This included work by Kathe Kollwitz, George Grosz, Otto Dix, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Erich Heckel, Paul Klee, Karl Schmidt-Rottluff, Max Beckmann, Christian Rohlfs, Oskar Kokoschka, Lyonel Feininger, Ernst Barlach, Otto Müller, Karl Hofer, Max Pechstein, Lovis Corinth, Georg Kolbe, Wilhelm Lehmbruck, Franz Marc, Emil Nolde, Willi Baumeister, Kurt Schwitters, Pablo Picasso, Jean Metzinger, Albert Gleizes, Piet Mondrian, Marc Chagall and Wassily Kandinsky.

The exhibition cleverly manipulated visitors to loathe and ridicule the art on show. As Nausikaä El-Mecky has pointed out: "The shock-value was enhanced by only allowing over-18s into the exhibition. The lines for the Degenerate Art Exhibition went around the block. Inside, many pictures had been taken out of their frames, and were attached to walls that were emblazoned with outraged slogans. Rather than whispering respectfully, people pointed and snickered. The paintings and sculptures had lost their status as artworks, and were now reduced to dangerous and outrageous rubbish." (32)

Visitors found that the works of art were "deliberately badly displayed, hung at odd angles, poorly lit, and jammed up together on the walls, higgledy-piggledy". They carried titles such as Farmers Seen by Jews, Insult to German Womanhood, and Mockery of God. "They were intended to express a congruity between the art produced by mental asylum inmates... and the distorted perspectives adopted by the Cubists and their ilk, a point made explicit in much of the propaganda surrounding the assault on degenerate art as the product of degenerate human beings." (33)

The objective was to "reveal the philosophical, political, racial and moral goals and intentions behind this movement, and the driving forces of corruption which follow them". The Nazis claimed that degenerate art was the product of Jews and Bolsheviks, although only six of the artists featured in the exhibition were actually Jewish. Jonathan Petropoulos, the author of Artists Under Hitler: Collaboration and Survival in Nazi Germany (2014) has pointed out that works were included "if they were abstract or expressionistic, but also in certain cases if the work was by a Jewish artist... The pictures were hung askew, there was graffiti on the walls, which insulted the art and the artists, and made claims that made this art seem outlandish, ridiculous." (34) One of the visitors commented: "The artists ought to be tied up next to their pictures, so that every German can spit in their faces - but not only the artists, also the museum directors who, at a time of mass unemployment, poured vast sums into the ever-open jaws of the perpetrators of these atrocities." (35)

The exhibition drew 2,009,899 visitors. After the exhibition closed, the work was confiscated. Among those who suffered included Emil Nolde (1,052), Erich Heckel (729), Karl Schmidt-Rottluff (688), Ernst Ludwig Kirchner (639), Max Beckmann (509), Christian Rohlfs (418), Oskar Kokoschka (417), Lyonel Feininger (378), Ernst Barlach (381), Otto Müller (357), Karl Hofer (313), Max Pechstein (326), Lovis Corinth (295), George Grosz (285), Otto Dix (260), Franz Marc (130), Paul Klee (102), Paula Modersohn-Becker (70) and Kathe Kollwitz (31). The campaign against "degenerate art" took in work by 1,400 artists in all. (36)

Kristallnacht

Kristallnacht (Crystal Night) began on the 10th November, 1938. Jewish homes, hospitals and schools were ransacked as attackers demolished buildings with sledgehammers and an estimated 30,000 Jewish men were arrested and sent to concentration camps. On 21st November, it was announced in Berlin by the Nazi authorities that 3,767 Jewish retail businesses in the city had either been transferred to "Aryan" control or closed down. Further restrictions on Jews were announced that day. To enforce the rule that Jewish doctors could not treat non-Jews, each Jewish doctor had henceforth to display a blue nameplate with a yellow star - the Star of David - with the sign: "Authorised to give medical treatment only to Jews." German bookmakers were also forbidden to accept bets from Jews. (37)

Emil Nolde reacted to these crimes in a letter to a friend where he commented that he could “understand” that “the operation for the removal of the Jews, who have burrowed so deep into all peoples” could not be carried out without “a lot of pain”. Not long afterwards, Nolde wrote to the Nazi press chief Otto Dietrich giving his support to Jewish persecution, explaining that he had spent his entire life fighting against the “too-great dominance of Jews in all matters artistic”. (38) December 6, 1938

Second World War

The Nazi government insisted that Nolde, despite his party membership, was not allowed to paint. Despite a personal appeal to his friend, Baldur von Schirach, this order was not changed and his art was considered "as ugly and anti-German in spirit, imbued instead with the polluting aesthetics of Africa, Bolshevism, and Jewry." Nolde retreated to his home in Sebüll, a remote area in Frisia, the northwest region of Germany "considered by many Germans to be the cradle of the nation’s language and culture. There, Nolde began crafting an image as a persecuted artist that he promoted to the Allies and his fellow Germans after the war." (39)

Ada Nolde wrote to a friend: "The most German, Germanic, most loyal artist is excluded. It is thanks for his struggle against foreigners and the Jews, thanks for his great love for Germany, despite the fact that it would have been so easy for him to move to the other camp due to the resignation of North Schleswig. But it is mainly thanks for the great art to which he dedicated his life. It is thanks for his membership of the party in which, despite many mistakes, he sees the solution to the people's problems." (40)

Nolde attempted to persuade Hitler of his loyalty by changing the subject matter. Nolde had reacted to the attacks on his "biblical figure paintings by not painting religious subjects after 1934 - and therefore no Jews either." Instead he concentrated on painting subjects that he thought the Nazi government would find acceptable: "Motifs from the Nordic world of legends increasingly took their place: kings, warriors and long-bearded Vikings. He was particularly inspired by Snorri Sturluson's collection of Icelandic royal legends... the first reading of this book led to a series of works with Viking motifs." (41)

On Hitler's death Nolde wrote: "He (Hitler) was my enemy. His cultural dilettantism brought my art and me much sorrow, persecution, and condemnation." (42) He now attempted to turn himself into the personification of the persecuted modern artist: "Cooperative art historians and politicians alike, needing to believe that there always was another Germany, a resistant and independent-minded Germany that, by whatever subterfuge, managed to quietly persist under the heel of Hitler’s regime... In order to forge a hero for themselves, they seized on the story of the painter condemned as degenerate and forbidden to paint.... Since Nolde neither painted overtly Nazi subjects nor changed his style to suit the Führer’s taste, that’s easier to do by way of texts than artworks." (43)

Emil Nolde died on 13th April, 1956. The Nolde Foundation Seebüll established by Ada and Emil in 1946, played an important role in the construction of the public Nolde image. (44) Art critics continued to protect Nolde's reputation and "It was a farce that most Germans were happy to entertain". In 2013, historian Manfred Reuther published his official biography Emil Nolde. Mein Leben (Emil Nolde. My Life), the 456-page book omitted any mention of Nolde’s admiration for Adolf Hitler and condensed his life during the Second World War to roughly five pages. (45)

Bernhard Fulda, the author of Press and Politics in the Weimar Republic (2009), carried out research into Emil Nolde at the Nolde Foundation. He was granted unrestricted access to archives containing more than 25,000 documents at the Nolde Foundation in Seebuell, near the Danish border, where the artist lived. This included a large number of anti-Semitic letters written by Nolde. Fulda's book, Emil Nolde: The Artist During the Third Reich, was published in May, 2019.

In September, 2019, Fulda and his wife, Aya Soika (an art curator) arranged an exhibition of Nolde's work in Berlin. According to the Times of Israel, "The exhibition includes documents from throughout Nolde's career, including anti-Semitic letters from the artist dating back to before World War I. It explores his conviction that he was a misunderstood artistic genius and his claim that he was boycotted by a supposedly Jewish-dominated art scene." (46)

Fulda and Soika also wrote the catalogue for the exhibition. The art critics who wrote the reviews relied heavily on their account of Nolde. Up until this time Angela Merkel was a great fan of his work. But after this bad publicity she removed Nolde's Breakers, a striking 1936 seascape, from a prominent place on her office wall. The painting was completely non-political but Merkel thought she could no longer be seen as liking his work. (47)

Primary Sources

(1) Michael H. Kater, Culture in Nazi Germany (2019)

Nolde's path in the Third Reich turned out to be one between acclamation and defeat, with defeat stealthily winning the upper hand. He was born Hans Emil Hansen in Nolde, Schleswig, the son of peasants, in 1867. Of Danish-German lineage, he was part of an ethnic minority that opted for life in the German Reich even under foreign citizenship. He became a carver and draftsman and in 1892 began creating watercolours of mountain motifis in Switzerland.

(2) Ralf Georg Reuth, Joseph Goebbels (1993)

After taking control of the film industry, Goebbels turned his attention to those trends in modern art that Rosenberg and his National Socialist Art Community had been attacking for years as "cultural bolshevism" - expressionism and abstract painting. As recently as June 1934 Goebbels had wanted national socialism, as the carrier of the most progressive modernity," to evaluate these new directions for their artistic contributions... In 1933 he brooded over the question of whether Emil Node was "a Bolshevist or a painter" and decided this would make a good dissertation topic.

(3) Barry Schwabsky, The Nation (19th September, 2019)

The paradox has long been noted: One of the most prominent modernist artists in Germany, Emil Nolde, was an enthusiastic supporter of Nazism, yet his art was roundly rejected by the Nazis and included in great quantity in their notorious 1937 exhibition “Entartete Kunst” (“Degenerate Art”), culled from works confiscated from German public collections and presented for derision as ugly and anti-German in spirit, imbued instead with the polluting aesthetics of Africa, Bolshevism, and Jewry. After the war, Nolde’s complicity was often overlooked, and he was remembered more as a victim of the Nazis rather than as an adherent. His story could be seen as a case study in the ambiguities, ironies, and absurdity of the intersection between art and politics in the 20th century.

But how, finally, to draw up the balance sheet the case of Nolde? History will judge, it’s often said. But on the contrary, it’s contemporaneity that judges, often in blindness and ignorance. History refrains; causes and consequences rather than rights and wrongs are its main business. Maybe it’s the sense that the time for judgment is running out that underlies the appearance of an exhibition such as “Emil Nolde: The Artist During the Nazi Regime” at the Neue Galerie at the Hamburger Bahnhof–Museum für Gegenwart in Berlin, a museum devoted to contemporaneity rather than art history. The living memory of those times is nearly gone; even people born in the early years after the war are now elderly. Now might be the last moment when settling these accounts really matters.

The polemical intention behind the exhibition, curated by Bernhard Fulda, Christian Ring, and Aya Soika comes across more clearly in the double entendre in its German title, “Emil Nolde: Ein Deutsche Legende”—a German legend, meaning, yes, Nolde counts as a legendary German artist, but also, more to the point, the story of his life as it’s been received in Germany has not been the truth but a myth, almost a fairy tale with which the country has assuaged its bad conscience.

The German title’s double meaning points, in turn, to a vacillation or ambivalence in the exhibition itself. On the one hand, it is a conventional career retrospective, with over 100 works tracing the artist’s development from 1899—two years after the then-31-year-old Nolde (at the time still Hans Emil Hansen) lost his post as a commercial drawing teacher and set out to fulfill his dream of becoming a fine artist—through 1951, when he stopped painting on canvas. (He continued to produce watercolors almost until his death at 88 in 1956.) On the other hand, it can be seen instead as an essentially documentary exhibition, a forensic dossier of original and reproduced evidence laying out a case to show that Nolde’s reputation was whitewashed in postwar Germany.

Cooperative art historians and politicians alike, needing to believe that there always was another Germany, a resistant and independent-minded Germany that, by whatever subterfuge, managed to quietly persist under the heel of Hitler’s regime, cultivated what the exhibition curators call “a one-sided emphasis on Nolde’s victim status.” In order to forge a hero for themselves, they seized on the story of the painter condemned as degenerate and forbidden to paint. An exhibition within the exhibition aims to demolish this legend - to clear away the whitewash from his reputation. Since Nolde neither painted overtly Nazi subjects nor changed his style to suit the Führer’s taste, that’s easier to do by way of texts than artworks. In this second exhibition, even the paintings and watercolors are documents - exhibits in the legal sense of the term - and in this context, even paintings and watercolors function more as documentation than as aesthetic artifacts (and in some cases, the curators have used copies of destroyed or unavailable works helpful in making their case)....

It was decided to hold a Great German Art Exhibition in Munich. Hubert Wilm, a pro-Nazi artist, explained what they were trying to achieve: “Representation of the perfect beauty of a race steeled in battle and sport, inspired not by antiquity or classicism but by the pulsing life of our present-day events”. Adolf Ziegler, signed the announcement for the competition. "All German artists in the Reich and abroad" were invited to participate. The only requirement for entering the competition was German nationality or "race". After extending the deadline for submissions, 15,000 works of art were sent in, and of these about 900 were exhibited. According to official records, the exhibition had 600,000 visitors.

Was this the seed for the painter’s growing anti-Semitism? It certainly added fuel to his lifelong martyr complex. In any case, it is after this that his correspondence begins to contain the poisonous complaint that it was the Jews who were blocking his way to success, that “the leaders of the Secession…are Jews, the art dealers are all Jews, likewise the leading art historians and critics, the whole press is at their disposal and the art publishers, too, are Jews.” Perhaps, too, we find in this episode the desire to distance himself from the metropolis and return to the borderland where he grew up, as he finally did in 1927, for “only in Berlin is it like this, although the movement’s long tentacles are now uncoiling over the whole land just like the dry rot spreading under the red-painted floors of our little home.” Needless to say, Nolde also had critics, dealers, and patrons in his corner. He was starting to have success; in 1913 his work for the first time entered a museum collection, in Halle. When Nolde published two volumes of memoirs in the 1930s, the volume chronicling his life from 1902 to 1914 was titled, naturally, Jahre der Kämpfe (Years of Struggle).

Anti-Semitism aside, Nolde’s psychology will sound familiar to anyone who has ever spent much time around artists. There’s a certain significant minority among them whose arrogant certainty that they have never been properly recognized - and somehow no amount of recognition may ever be quite enough—tends to devolve into fantasies of persecution, the feeling that some cabal or mafia is arrayed against them. For Nolde, this was the Jews. In another time and place, this obsession might have remained a private affair, known only to a few intimates, but Nolde had the moral bad luck to be a contemporary of the Nazis, of whom he became an early and avid supporter...

After the war, Nolde did his best to scrub his reputation as clean as possible. Correspondence could be suppressed and unpublished manuscripts destroyed, but the public record could not be denied. Admiring critics and curators believed they had to save the great artist from the consequences of his worst tendencies, from what one writer called “the most dangerous understanding, his own interpretation of himself.” They helped solidify the myth of the “persecuted ‘pioneer of a new German art,’” as a wall text puts it - a victim of Nazi repression who intransigently bided his time during the worst of it. The effort was a success. Former German chancellor Helmut Schmidt was a great champion of Nolde’s, lamenting to Henry Kissinger the artist’s relative obscurity in the United States, and the current chancellor, Angela Merkel, was also an enthusiast.

(4) Jonathan Jones, The Guardian (12th February, 2018)

I don’t usually notice the frames on paintings, let alone mention them in a review, but those that enclose the German expressionist Emil Nolde’s seething rectangles of lurid colour are unusually beautiful and striking. Most of the paintings in the National Gallery of Ireland’s courageous and revelatory survey of this great modern artist are enclosed in stark black frames that superbly set off the glow of his yellows, reds and greens. This way of framing his art was favoured by Nolde himself. It heightens his wonderfully eerie effects.

Two young people look at us out of mask-like, lamplit faces from his 1919 painting Brother and Sister. They look decadent, amoral. Does the indefinably sexual aura hint at incest?

When Picasso and Matisse were shattering form and liberating colour in Paris, this artist, born in 1867 on the border between Germany and Denmark, was taking the same kinds of risks, but with a more anxious, introspective, soul-searching edge.

Expressionism was a self-consciously north European art movement, pioneered by Van Gogh and Munch and taken up in the 1900s by young German artists including Nolde, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner and Max Pechstein. In 1906, a year before Picasso painted Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, they formed a group called Die Brücke - “The Bridge”. So much for the textbook version of art history. What this exhibition gets across, in an electrifying and visceral way, is the primal rawness of Nolde’s restless genius...

It is Nolde’s social angst and psychic turmoil that holds me gripped. Like Munch’s Scream, his paintings are desperate dives into modern fear. His 1911 work Still Life of Masks I is an uncanny collection of false faces. One mask has a wide open mouth and look of terror – it is the face of Munch’s screaming figure, made into a mask here long before it became a horror film trope and Halloween costume...

Nolde was in his 60s when Hitler came to power in 1933. He joined the Nazi party and was patronised by Himmler. Like Wagner before him, he was both a vicious antisemite and a revolutionary creative figure. No wonder we’d rather keep him as a footnote to the history of modern art.

In fact, the Nazis themselves provided an alibi of sorts for anyone wanting to admire Nolde’s artistic brilliance, while separating him from the genocide of millions that was the ultimate result of views like his.

In 1937, more than 1,000 of Nolde’s works were denounced as “degenerate art” and removed from German museums. That same year, 33 of his paintings were included in the , along with works by Picasso, Klee and many more. These artists were mocked as decadent imitators of “primitive” art; Nolde truly did admire non-European art. His 1911 painting Exotic Figures is a still life of ethnographic museum pieces. More hauntingly, his 1913 work gives an imaginary human figure the face of an Easter Island statue.

Nolde, paradoxically, has a true appetite for otherness. The fear in his art is always laced with desire. Just before the first world war he visited New Guinea, and the portraits and watercolours he made there are full of admiration for what he seems to see as a pure, natural way of life. They may be racist by 21st-century standards, but I would argue that they are not hateful. Under the influence of Gauguin, he seems to be looking at otherness with fairly open eyes.

Yet it would be dishonest and cowardly to try to clean up Nolde and pretend his victimisation as a degenerate artist cancels out his keen support for Hitler. The admiration he expresses for New Guinea’s warriors resembles the enthusiasm that later made Leni Riefenstahl photograph the Nuba people. For the Nazi mind, it was not non-European peoples who were the racial enemy. The fear and loathing in Nolde’s art are directed at demonised Jewish caricatures.

This terrific modern visionary is demonic in every sense. We should never stop looking into his distorting mirror where the extremes of imagination and hate can both be seen and the wound of modern history will never heal.

(5) Catherine Hickley, The Art Newspaper (10th April 2019)

Emil Nolde has long been one of the most popular German Modernists, loved especially for his Expressionist landscapes and flowers. His biography, however, has undergone much whitewashing over decades, and it is only now that the full, unvarnished truth is starting to emerge. His biography is the subject of an exhibition, opening at the Hamburger Bahnhof museum in Berlin this week, that aims to deconstruct myths surrounding his legacy.

Nolde’s art was condemned as “degenerate” by the Nazis, and no other artist had as many works confiscated or displayed as prominently in the 1937 Degenerate Art exhibition ordered by the Nazi politician Joseph Goebbels to ridicule and shame Modern artists. But the artist was also an ardent anti-Semite and a member of the Nazi party whose faith in Adolf Hitler remained unshaken until the end of the Second World War.

Over many decades, first Nolde himself, and then - after his death in 1956 - the foundation established to manage his estate, emphasised his victimhood and played down his complicity with the Nazis. It is only since Christian Ring, a banker-turned-art-historian, took over the management of the foundation in 2013 that this has changed. In 2016, the foundation admitted “the promotion of mistaken interpretations and legend-building, without sufficient portrayal of the contradictions in Emil Nolde’s biography”.

“Emil Nolde’s art was persecuted, but the man Emil Nolde wasn’t really,” Ring says. “It was time to put all the cards on the table.” Ring gave full access to around 25,000 unpublished letters and documents in the foundation’s archive in Seebüll, in northern Germany, to Aya Soika, an art historian at Bard College Berlin, and Bernhard Fulda, a historian from Cambridge University, for independent analysis. Soika, Fulda and Ring have jointly curated the exhibition.

Among the exhibits will be examples of Nolde’s so-called “unpainted pictures”, a key part of the legend-building around him. These were small-format watercolours he was reputed to have painted secretly in Seebüll at a time when he was supposedly banned from painting - he was, in fact, only banned from exhibiting. The show will also look at the extent to which Nolde’s Nazi sympathies influenced works such as his depiction of mythic sacrificial scenes and portrayals of Nordic people.

The exhibition is organised in collaboration with the Nolde Foundation Seebüll and supported by the Freunde der Nationalgalerie and the Friede Springer Foundation. It is accompanied by a catalogue published in English and German by Prestel Publishing.

(6) Brendan Simms & Constance Simms, The New Statesman (4th September 2019)

Sometimes, Siegfried Lenz writes in his acclaimed novel Deutschstunde (or The German Lesson, 1968), the “anchor of memory” does not take root but “rattles” and “jangles”, “stirring up mud” as it drags along the sea bed, destroying the tranquillity needed “to throw a veil over the past”. Ironically, Lenz’s book itself threw a veil over the renowned expressionist artist Emil Nolde (born Emil Hansen), the real-life figure on whom the book’s painter hero, Nansen, was based. It has taken the determined efforts of a Cambridge historian, Bernhard Fulda, and the Berlin art historian Aya Soika to rip off the veil that Nolde himself and the many guardians of his legacy had woven so carefully.

Until recently, the Nolde most of us knew was the man he wanted us to see. “Hitler is dead, he was my enemy,” Nolde wrote a few days before Germany surrendered in early May 1945. The artist put it about that the regime had forbidden him to paint, but that he had produced “unpainted pictures” in defiance of Gestapo surveillance. This notion drove the plot of Deutschstunde, as well as a major two-part adaptation for German television in the early 1970s, and is at the heart of an unfortunately timed new adaptation of the novel for the big screen by director Christian Schwochow.

But thanks to a current exhibition at the Hamburger Bahnhof in Berlin – curated by Fulda, Soika and the courageous director of the Nolde Foundation, Christian Ring – all that has changed. “Emil Nolde: A German Legend. The Artist during the Nazi Regime” not only draws together all the material already in the public domain, which is incriminating enough, but also provides copious fresh evidence from the artist’s private correspondence. The exhibits of original letters are supported by two massive volumes of essays and documents. Nolde emerges not merely as a committed National Socialist from the beginning to the end of the Third Reich, but also as a fervent anti-Semite.

Nolde, in fact, was an anti-Semite, or at least in the grip of an anti-Semitic world view, long before Hitler took power. As early as 1911 he drew a distinction between “Jews” and “Germans” and claimed that the leaders of the Berlin Secession art movement, such as Max Liebermann, Lovis Corinth and Max Pechstein, were Jews. Nolde added that “the art dealers are all Jews”, as were the “leading art critics” and that “the entire press was at their disposal”. He went on at length in this vein, culminating with the allegation that the Secession movement was spreading like “dry rot” throughout the country. In the same letter the author claimed to be “no anti-Semite”, but his adherence to a classic anti-Semitic trope cannot be gainsaid. Twenty years later, and more than a year before the Nazis took over, Nolde wrote that “the whole Soviet system was of Jewish origin and served Jewish interests”, which were to use “the power of money” to gain “world domination”.

With the coming of the Third Reich, Nolde let the mask drop completely. He not only denounced his fellow artist Pechstein as a “Jew” (he wasn’t), but in the summer of 1933 drafted a plan, which he later destroyed, for how to remove Jews from German society. And unfortunately for him, plenty of other evidence has survived. In the autumn of 1938, for example, Nolde wrote that one could “understand” that “the operation for the removal of the Jews, who have burrowed so deep into all peoples” could not be carried out without “a lot of pain”. Not long afterwards, Nolde wrote to the Nazi press chief Otto Dietrich that he had spent his entire life fighting against the “too-great dominance of Jews in all matters artistic”. In November 1940, he praised Hitler’s speech on the anniversary of the failed Munich Beer Hall Putsch of 1923, especially the passages attacking “the Jews”.

If this was not clear enough, Nolde responded to the famous Dambuster raids in 1943, which Nazi propaganda attributed to the machinations of German-Jewish refugees, with “the war is becoming more and more ‘the Jewish War’”, adding that “they” were assiduous in pursuing their “plans for domination”. Not long after, Nolde elaborated that “a handful of smirking Jews hiding behind the governments and banks of their world powers” (meaning the United States and the British empire) were “financing and stoking this global brutal war”. The Jews, he continued, wanted to “destroy” Germany in the interests of “Jewish world domination”. In short, Nolde’s Nazism, and his essential complicity with the regime, is indisputable.

What saved Nolde, until now, was Hitler’s unrelenting hostility to his art. In the same year as he took power, the Führer repeatedly described Nolde as a “pig” and swore that he would not spend a penny of the new regime’s money on giving him commissions. Hitler also announced that gallery directors would be instructed not to buy any more of his works on pain of imprisonment. Nolde’s painting, he averred, was just a “pile of manure”.

(7) Mary M. Lane, Art News (12th September, 2019)

On November 9, 1933, German artist Emil Nolde attended what he considered his most important networking event to date: a dinner party with Adolf Hitler commemorating the 10th anniversary of the Beer Hall Putsch, the failed coup in which some 2,000 Nazis in Munich attempted to seize power from the Bavarian government. “The Führer is great and noble in his aspirations and a genius man of action,” Nolde wrote in a letter to a friend after the soiree, noting that Hitler “is still being surrounded by a swarm of dark figures in an artificially created cultural fog.” The “dark figures” to which he referred were Jewish Germans who, the artist believed, sought to destroy what he considered “pure” German art through cultural diversity.

Nolde, then 66 years old, was aware that he was a test case for Hitler and his sycophantic propaganda minister, Joseph Goebbels. Revered as a founding father of 20th-century German Expressionism, he had nonetheless generated controversy among Nazi elites for respectfully depicting a wide variety of subjects, including ethnic minorities. He did not paint in the hyperrealistic style that Hitler preferred, favoring instead bold brushstrokes and electrifying colors to evoke visceral feelings of primal passion.

But Nolde was determined to enter Hitler’s good graces. A year after meeting at the dinner party, he wrote an autobiography modeled on Hitler’s Mein Kampf - with Nolde’s titled Jahre der Kämpfe (or Years of Struggle, using the plural of “Kampf”). And he advocated eugenics: “Some people, particularly the ones who are mixed,” he wrote in his book, “have the urgent wish that everything - humans, art, culture - could be integrated, in which case human society across the globe would consist of mutts, bastards and mulattos.”

Nolde’s attempts to ingratiate himself with the genocidal Nazi regime did not go as planned. Displeased with his Expressionist style, Hitler featured more works by Nolde than any other artist in his notorious 1937 “Degenerate Art” exhibition (which included 27 of Nolde’s paintings, watercolors, and etchings) and confiscated 1,052 Nolde works from German museums. Stung, the artist retreated to his home in Sebüll, a remote area in Frisia, the northwest region of Germany considered by many Germans to be the cradle of the nation’s language and culture. There, Nolde began crafting an image as a persecuted artist that he promoted to the Allies and his fellow Germans after the war...

After the artist’s death, in 1956 at the age of 88, the Nolde Foundation (or Nolde Stiftung in German) worked to hide his racist past. But recently the foundation has started to acknowledge the dark side of history—as evidenced by an exhibition at Berlin’s Hamburger Bahnhof museum that opened this summer and remains on view through September 15. “Nolde: A German Legend, the Artist in National Socialism” (the title on display at the museum, as opposed to its online mantle “Emil Nolde. A German Legend. The Artist during the Nazi Regime”) is the first attempt by the foundation to break the German public’s impression of Nolde as a victim of Hitler’s regime rather than an advocate for his anti-Semitic worldview.

For many years, Bernhard Fulda and Aya Soika, a husband-and-wife team well-respected in the international art research community and co-curators of the show with Christian Ring, the head of the Nolde Foundation, tread a fine line with Nolde’s legacy. Though they have published numerous articles shedding negative light on the artist—most notably a 2014 catalogue essay for an exhibition at Neue Galerie in New York—they have done so with caution. “For decades, the foundation did really sit as gatekeepers on all this archival material,” Fulda told ARTnews. “Access to his written legacy has been notoriously difficult.”

That changed when Ring took over in 2013, ending a long history of what Fulda called “the artist’s marketing campaign,” and the exhibition marks the first time Nolde’s racist views have been fully exposed. To expedite the transparency, the exhibition’s hefty catalogue has been published in both German and English, a bilingual gesture often avoided with controversial German exhibitions.

The show opens with Pentacost (1909), a painting that fueled Nolde’s anti-Semitism when it was rejected for an exhibition by the Berlin Secession, an artist group founded in 1898 in opposition to European salons and as a defender of traditional German culture. Nolde was deeply attached to the work depicting the visitation of the Holy Spirit upon Jesus Christ’s apostles after their savior’s death and resurrection, and after its dismissal he wrote a scathing letter to Berlin Secession president Max Liebermann that leaked to the press, much to Nolde’s horror. The episode, according to Fulda and Soika, led Nolde to give serious weight to the idea that Liebermann, a Jewish German, and what Nolde called the “Jewish-dominated” press were subverting true German culture. “Throughout his life Nolde suffered from negative art-criticism,” the researchers write in the exhibition catalogue, “and in this anti-Semitic conspiracy theory he found something it could be convincingly attributed to.”

Rather than deflecting the subject of anti-Semitism by focusing on Nolde’s most iconic works, including his nine-part 1912 masterpiece The Life of Christ, the curators chose to focus on art by Nolde that reflects the racist myth of Nordic superiority in which he believed even after the Nazis rejected his work. In 1938, Nolde created the luminous blue and golden watercolor Mistress and Stranger as part of a series celebrating vikings that counted as a failed attempt to have Hitler reconsider his fate when he refused to paint the Nordic subjects in the realistic hues that the Führer preferred. In Three Old Vikings, a trio of warriors are fierce and ready to fight - but unusually colored in fiery burnt orange and saffron. In Veterans, two soldiers stare out with stoic, determined faces and clenched jaws, yet Nolde thwarted his mission once more by painting their skin an odd golden hue.

After the war, Nolde touted these and other works as a sign of his bravery against the Nazis - a position thoroughly debunked by the exhibition. A quote from Nolde’s wife Ada prominently displayed in the Hamburger Bahnhof boasts that the couple had stood “fully and completely behind our Führer” long after other Germans had denounced him. And a lengthy essay in the catalogue (and excerpted in the exhibition) analyzes the anti-Semitism in Nolde’s Jahre der Kämpfe.

“He is an artist we would not normally celebrate: an anti-Semite, someone who joined the Nazi party and who for the rest of his life never apologized,” Fulda said. The previously predominant view of Nolde as a wartime victim owed much to the Nolde Foundation’s tight grip on his reputation, and it was also influenced, Fulda said, by the fact that many past historians, curators, and journalists might have not wished to offend living relatives who may have been admirers of the Nazi regime themselves.

But all the recent research has started to lead to change. Earlier this year, German Chancellor Angela Merkel removed Nolde’s Breakers, a striking 1936 seascape, from a prominent place on her office wall. And revelations about the artist’s past of the kind on display in Berlin may stand to change thoughts about his work forever. “Whenever people think that art and cultural context are entirely distinct spheres - [that] art is totally autonomous - they are kidding themselves,” Fulda said.

But Fulda and Soika’s role as historical researchers is only part of an equation that includes viewers, too. “We don’t pass any judgment in that regard,” Fulda said. “We don’t say, ‘This is what you should do with this cultural context.’ We tell art lovers: ‘Deal with it - now you figure out how this new knowledge frames the artworks of Nolde that you’re seeing.’”

(8) Rob Weinberg, Apollo Magazine (9th August, 2018)

At the outset of the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art’s comprehensive survey of the work of German Expressionist Emil Nolde (previously at the National Gallery of Ireland), one picture is particularly striking. In his Self-portrait of 1917, Nolde’s white tunic and hat, yellow face and penetrating blue eyes are rendered with the same intense impasto as the ground and sky that vibrate around him. The artist is demanding that we see him as one with the elements.

Between this arresting overture and the dazzling conclusion of Large Poppies of 1942, in the final room, the visitor is taken on a voyage through the varied subjects that caught Nolde’s eye: from farmers working the land to decadent Berlin nightlife; from his own carefully cultivated gardens to turbulent seascapes and biblical scenes. Through them all, true to the exhibition’s title Emil Nolde: Colour is Life, it is the artist’s voracious appetite for colour that emerges as the main subject.

Nolde was at the forefront of a generation of German artists who eschewed saccharine Impressionism for a new, emotionally charged vocabulary. His debt to both his forebears and contemporaries is evident: the harrowing realism of Grünewald rubs shoulders with the heartfelt, early depictions of peasants by Nolde’s great hero Van Gogh; haunted, Ensor-like masks jostle with something like the gaiety of Toulouse-Lautrec. At various points in his career he flirted with the Expressionist group Die Brücke in Dresden, with the Berlin Secession, and Kandinsky’s Der Blaue Reiter. But he never fitted easily into one school.

The artist was born Hans Emil Hansen into a farming family in the village of Nolde in Southern Jutland. Early experience of farming gave way to the demi-monde of Berlin’s cabaret scene where Nolde’s wife Ada Vilstrup worked as a dancer. Its louche characters and hubbub inspired vivid graphics, stage-lit in watercolour. The port of Hamburg also caught his eye. Hastily brushed, monotone suggestions of boats and waves are the most subtle works on show. For an artist best known for his attraction to the visceral, it is a revelation to find calm here in his approach to line and space.

Nolde’s depiction of Israelites in his Bible paintings would not have been out of place on a Nazi-propaganda pamphlet. He was a declared anti-Semite who aligned himself with the Nazis in the hope it would put him at the centre of the party’s cultural policy. His move backfired; more than 1,000 of his works were confiscated and some 33 of them – more than by any other artist – were selected for the Degenerate Art exhibition in Munich in 1937. During those turbulent years, when Nolde was barred from working as an artist, he produced an extensive series of ‘unpainted pictures’ – line and wash drawings of fantastical, Redon-esque figures. Some are enchanting. But the foreshortened Skater (c. 1930s–40s) resembles more an isolated, blindfolded victim, bound up in one of Francis Bacon’s bleak rooms.

Along with religion, the landscape exerted a fascination for Nolde. In paintings like Light Breaking Through (1950), the meteorological mood of northern Europe is captured with the full force of Nolde’s brush. Waves crash and churn; the oppression is tangible. It feels as though nature became Nolde’s metaphor for the turbulence of his time.

(9) Geir Moulson, Times of Israel (11th April 2019)

A Berlin museum has opened an exhibition based on years of research into expressionist painter Emil Nolde that chips away at the remnants of his image as a victim of the Nazi regime.

Nolde, who died in 1956, was among the prominent artists whose work was condemned as “degenerate art” under Nazi rule. But he was also a Nazi party member and, as the exhibition presented Thursday at the Hamburger Bahnhof museum shows, an anti-Semite and believer in Nazi ideology who held out hopes of winning the regime’s recognition even after he was banned in 1941 from exhibiting, selling and publishing his work.

“Our view of Nolde will have to change, and our thinking about this artistic figure will have to be a different one,” museum director Udo Kittelmann told reporters. “It is only now obvious how systematically he ingratiated himself with Nazism and particularly its anti-Semitism.”

The exhibition is the result of a research project that started in 2013. Historians and curators Aya Soika and Bernhard Fulda were granted unrestricted access to archives containing more than 25,000 documents at the Nolde Foundation in Seebuell, near the Danish border, where the artist lived.

The exhibition includes documents from throughout Nolde’s career, including anti-Semitic letters from the artist dating back to before World War I. It explores his conviction that he was a misunderstood artistic genius and his claim that he was boycotted by a supposedly Jewish-dominated art scene.

In 1937, however, 48 Nolde works were taken from German museum collections to become part of the Nazis’ traveling “degenerate art” exhibition. Nolde wrote to propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels asking him to end the “defamation” of his work and trumpeting his “fight against the foreign infiltration of German art.” He did succeed in getting some works returned, and meanwhile produced a series of “Viking Paintings” more in tune with the tastes of the time.

Nolde, whose Nazi party membership has long been known, was exonerated in the post-war denazification process, largely because of his ban from exhibiting. His work later found a place in the offices of Chancellor Helmut Schmidt and, more recently, Merkel.

Merkel hasn’t commented on giving up the Nolde paintings from her office, beyond saying she’d been asked to return the loan. She also hasn’t given a reason for deciding against hanging two replacement works she was offered by Karl Schmidt-Rottluff, another expressionist whose work was classified as “degenerate” but who is known to have made anti-Semitic statements during WWI.

After the war, the perception of the Nazi era was that “there were perpetrators, followers and victims, and Emil Nolde could, thanks to the ‘degenerate art’ campaign, easily be classified in the group of the victims,” Nolde Foundation director Christian Ring said. “Emil Nolde has a lot to thank Adolf Hitler’s reactionary taste in art for.”

Ring conceded that, after the war, the foundation contributed to upholding Nolde’s misleading image.

“Today, more than 50 years later, we in Seebuell no longer see any reason to protect Nolde from himself,” he said. “His art, which was pioneering for expressionism and modernism, is strong enough to withstand the discussion about his relationship with Nazism.”

(10) Bernhard Fulda & Aya Soika, Emil Nolde in National Socialism (2019)

The last aspect, which can only be summarized here, concerns the anti-Semitism of Emil and Ada Nolde. Anti-Semitic remarks were documented early in Nolde's correspondence. In 1911 he compared the alleged liaison between "painter Jews", art criticism and art trade with a "sponge overgrowth". At the end of 1931 he took up the anti-Semitic myth of Judao-Bolshevism‹ and pondered in a letter about its relationship to a capitalist Jewish city culture. He publicly criticized German Impressionism as "hermaphrodite art", among other things in early 1932 in his defense of the controversial international exhibition Modern German Art, which - organized by employees of the Berlin National Gallery - deliberately avoided German Impressionists. In April 1933, shortly after Hitler was appointed Chancellor, Nolde wrote a letter to Max Sauerlandt asking for a divorce within the arts between "Jewish and German art, as well as between Franco-German mixture and purely German art." It was clear to Nolde that his artistry was compatible with the ideas of the National Socialist young 'movement' - especially because of its anti-Semitism. In the spring of 1933, he denounced the painter Max Pechstein as an "Jew" to an official in the Ministry of Propaganda; thereupon he was officially informed by the Prussian Academy of the Arts that Pechstein was a "purely Aryan descent". During those months, Nolde was working on a “dejudication plan” that he wanted to submit to Hitler. The plan is mentioned in letters, but has not survived. In the second volume of his memoir, Years of the Fights, published in autumn 1934, Nolde gives a hint at his ideas about a territorial solution to the so-called Jewish question‹, which contains various anti-Semitic passages. In this book, particular attention is paid to the description of his conflict with Max Liebermann and the Berlin Secession, which he subsequently stylized as "rebellion against the Jewish power that reigned in all the arts." At the end of 1934, a leaflet from Rembrandt Verlag referred to this episode in detail in order to advertise the book with the help of press quotes that Nolde, for example, as a pioneer "against the oppressive dictatorship of the Jewish art trade and domination against the French-Impressionist circles. In September 1934, Nolde - as a Danish citizen - joined the National Socialist Working Group North Schleswig (NSAN), which was brought into line the following year with the founding of the National Socialist German Workers' Party North Schleswig (NSDAPN). Nolde repeatedly referred to his party membership, among other things to prevent reports in the press that associated him with the allegedly Jewish culture of the Weimar period. In December 1938 he wrote a draft 6-page letter to NSDAP Reichspressechef Otto Dietrich, which contains numerous anti-Semitic passages; Nolde had recently been listed in a daily newspaper together with Jewish protagonists of cultural life under the title "The enemy in one's own country - Jews as cultural Bolsheviks".

Nolde anti-Semitism is already very pronounced in this reaction - written a few weeks after the anti-Jewish November pogroms in 1938; it continued to increase during the Second World War. During these years, Emil and Ada Nolde followed the war reports intensively: they received Nazi propaganda on their radio and their local newspaper every day. They marked the course of the fighting on a map of Europe in the house. Despite the 1941 ban and rumors of "horrible true things from Poland," to which Ada brought her husband's attention, they held firm to their beliefs. The couple's correspondence during Ada Nolde's two-month hospital stays in Hamburg-Eppendorf in 1942 and 1943 provides insights into the Noldes' worldview and anti-Semitism.

In the spring of 1943, after the discovery of the mass graves near Katyn, where Polish officers were shot by the Soviet NKVD in 1940, the Nazi war propaganda reached its anti-Semitic peak. This is also reflected in Nolde's aphorisms, which the artist later wanted to publish - along with a selection of his Unpainted Pictures. On small pieces of paper he records his thoughts on artistry, God and world events. After Easter 1943, he sent four of these small sheets to Ada in a letter, in which he inscribed himself in a great process of world history and religion. In them culminated Nolde's longstanding self-stylization as a misunderstood pioneer against Judaism. In fact, these diary-like aphorisms, which will later be called “words on the edge”, play a special role in Nolde's autobiographical work. The notes from the spring of 1943 show how strongly Nolde's anti-Semitism radicalized under the influence of war propaganda. The aphorisms that Nolde wrote from the spring of 1945, on the other hand, certainly testify to the subsequent attempt to distance himself from Hitler and the Nazi dictatorship. After the war ended, Nolde destroyed most of his political considerations that arose before May 1945. Some of the notes escaped this self-cleaning process only because - enclosed with the letters to Ada - they were forgotten by the artist. The "words on the edge" that he consciously received were so important to him that he made a will to implement the publication he had planned posthumously.

When the Nolde Foundation Seebüll took on an important role in the construction of the public Nolde image after Nolde's death in 1956, new editions of Nolde's memoirs were cleaned of the grossest anti-Semitic passages, his "words on the edge" were only published in excerpts and also problematic statements the correspondence kept in the estate remains inaccessible.

The central question that arises in the context of the research is whether and to what extent Nolde's ideological conviction is reflected in the artistic work. In reply to Nolde's political stance, it was repeatedly emphasized that he had made no concessions to National Socialism in his art and therefore remained autonomous and 'resistant'. In fact, however, a number of motivic changes in the work can be observed after 1933: Nolde reacted to the attacks on his biblical figure paintings by not painting religious subjects after 1934 - and therefore no Jews either. Motifs from the Nordic world of legends increasingly took their place: kings, warriors and long-bearded Vikings. He was particularly inspired by Snorri Sturluson's collection of Icelandic royal legends. Even before 1914, the first reading of this book led to a series of works with Viking motifs; in the summer of 1936 the Nolde couple again immersed themselves in this Nordic world of legends. Probably in response to the Degenerate Art exhibition, Nolde elaborated three of his small-sized Viking watercolors into paintings in the summer of 1938. These emerged at the same time that Nolde characterized his art in a letter of protest to Minister of Propaganda Joseph Goebbels as "German, strong, bitter and intimate". Less well known in Nolde's oeuvre is the mystical motif of mountains, castles and sacrificial fires, which complemented Nolde's penchant for a Nordic theme, particularly in the 1930s and early 1940s. Since his time as a young drawing teacher in St. Gallen in the 1890s, when Nolde became an enthusiastic mountaineer, the artist never lost his fascination with the mountains. After a gastric cancer operation in 1935, the Nolde couple spent a few weeks in the Alps almost every year from 1936 to 1941, where Nolde also painted watercolors. The numerous castle ruins and mountain chapels in Graubünden and Vorarlberg fueled his romantic imagination. In addition - presumably after the outbreak of war in 1939 - there is a fascination with fire and destruction. Around 1940, Nolde transferred some of the watercolors with a clearly Nordic theme in oil. He placed three such paintings prominently in the picture room (now known as the picture room) in Seebüll: The Holy Fire, Holy Victim and Veterans. It can thus be seen that Nolde developed new focal points both in the choice of motif and in artistic self-portrayal during the Nazi era.