1937 Degenerate Art Exhibition

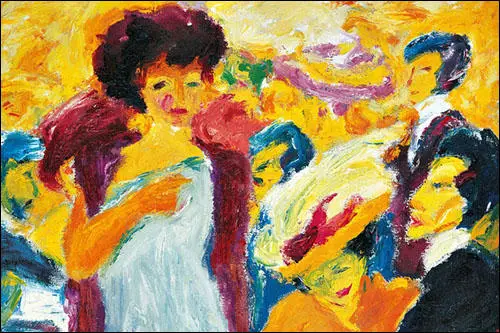

In 1932 Paul Schultze-Naumburg, a senior figure in the Nazi Party, wrote a pamphlet entitled, The Struggle for Art: "We know that, from the works of art that the peoples and the times have left us, we can draw a picture of their true spiritual essence, form and environment... After all, one cannot ignore that the higher task of the artist is to show the final objectives to the people of their time, to make visible the image towards which one wishes to move, so that all people could recognize beauty and can start the contest to imitate it and to make themselves compliant with that ideal... Woman has probably never been depicted so disrespectfully and in so unappetizing a way as in the paintings we have been obliged to put up with in German exhibits of the last twelve years, paintings that inspire only nausea and distrust. They convey not the slightest trace of the sacredness of the human body or of the glory of a divine nakedness. They express a ravening lasciviousness that sees the nude only as an undressed human being in its lowest form... The essential element of art, as we understand it, is therefore to always show a ‘spiritual direction’. And the idea of National Socialism is based on appropriately 'giving direction' to the German people and leading it to salvation. And since that task is substantially conducted with spiritual tools, national socialism cannot ignore the instrument of art." (1)

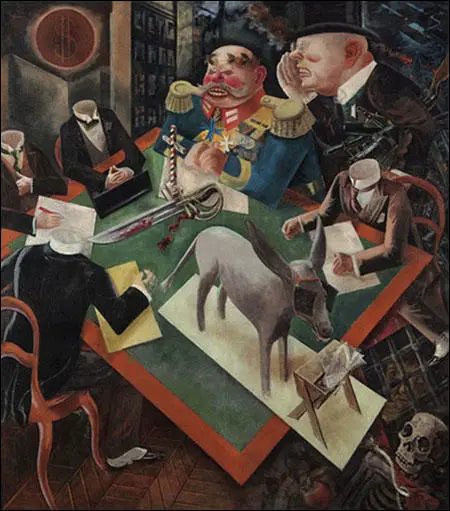

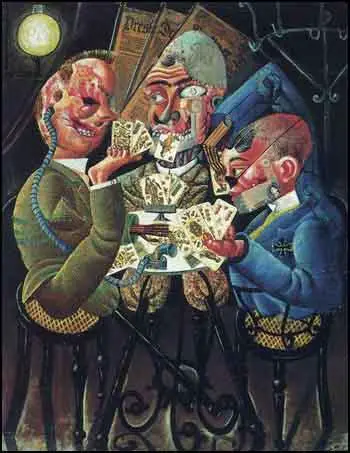

Adolf Hitler took a keen interest in art and saw it as a means of promoting fascism and changing attitudes in Germany. He was especially angry about the popularity of left-wing and anti-war artists such as Käthe Kollwitz, John Heartfield, George Grosz and Otto Dix. Hitler agreed with Schultze-Naumburg when he wrote: "A life-and-death struggle is taking place in art, just as it is in the realm of politics. And the battle for art has to be fought with the same seriousness and determination as the battle for political power." According to Berthold Hinz, the author of Art in the Third Reich (1979): "This issue became a touchstone for determining who were the friends and who were the foes of the Third Reich". (2)

Adolf Ziegler

Soon after Adolf Hitler gained power he appointed Adolf Ziegler, a strong supporter of Schultze-Naumburg, as his artistic adviser. Joseph Goebbels, the head of the Culture Ministry. At the time Goebbels did not share Ziegler's views on modern art and liked artists such as Emil Nolde, Erich Heckel and Ernst Barlach. As a student at university he had regularly attended lectures in art history. In March 1934 he had served as a honorary patron of an exhibition on Italian Futurism in Berlin. (3) In a speech made in June 1934 Goebbels argued "We National Socialists are not un-modern; we are the carrier of a new modernity, not only in politics and in social matters, but also in art and intellectual matters." (4)

In January 1934 Hitler had appointed Alfred Rosenberg as the cultural and educational leader of the Reich. Ziegler got support from Rosenberg in his disagreement with Goebbels. Rosenberg saw his mission to preserve the "folkish ideology in its purest form" and rejected Goebbels's belief that artists such as Heckel, Nolde and Barlach were representative of contemporary Germany's "indigenous Nordic" art. (5)

Hitler was asked to intervene in the dispute. He made his position clear in a speech in September, 1934. Hitler argued that there were "two dangers" that National Socialism had to overcome. First, the iconoclastic "saboteurs of art," were threatening the development of art in Nazi Germany. "These charlatans are mistaken if they think that the creators of the new Reich are stupid enough or insecure enough to be confused, let alone intimidated, by their twaddle. They will see that the commissioning of what may be the greatest cultural and artistic projects of all time will pass them by as if they had never existed." (6)

Reich Chamber of Fine Arts

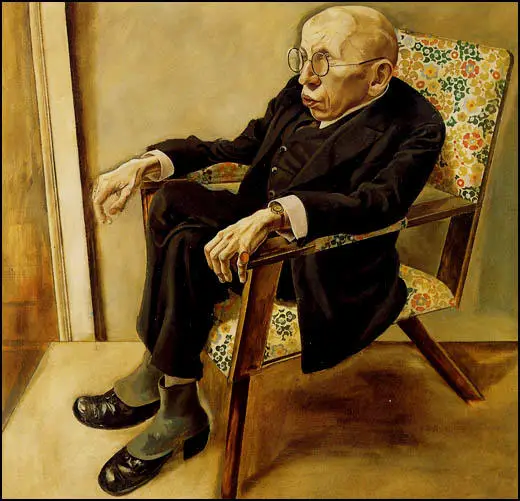

In 1936 Adolf Ziegler became President of the Reich Chamber of Fine Arts (Reichskammer der bildenden Kuenste), a subdivision of the Cultural Ministry under Joseph Goebbels. (7) Ziegler made all artists join the Reich Chamber of Fine Arts. In this way it became possible to prevent artists who were opposed to the policies of the Nazi government from working. For example, Otto Dix had to promise to paint only inoffensive landscapes or portraits. However, he was eventually sacked as professor at the Dresden School of Arts and Crafts. Dix's dismissal letter said that his work "threatened to sap the will of the German people to defend themselves." (8)

In June 1936, Joseph Goebbels wrote in his diary: "Horrible examples of art Bolshevism have been brought to my attention... I want to arrange an exhibit in Berlin of art from the period of degeneracy. So that people can see and learn to recognize it." (9) By the end of the month he had obtained Hitler's permission to requisition "German degenerate art since 1910" from public collections for the show. Goebbels actually liked modern art and was a collector of the work of Emil Nolde. As Richard J. Evans has pointed out: "Its political opportunism was cynical even by Goebbels's standards. He knew that Hitler's hatred of artistic modernism was unquestionable, and so he decided to gain favour by pandering to it, even though he did not share it himself." (10)

On 27th November, 1936, Goebbels issued the following decree: "On the express authority of the Führer, I hereby empower the President of the Reich Chamber of Visual Arts, Professor Ziegler of Munich, to select and secure for an exhibition works of German degenerate art since 1910, both painting and sculpture, which are now in collections owned by the German Reich, by provinces, and by municipalities. You are requested to give Professor Ziegler your full support during his examination and selection of these works." (11)

Ziegler and his entourage toured German galleries and museums and picked out works to be taken to the new exhibition, some museum directors were furious, refused to co-operate, and pleaded with Hitler to obtain compensation if the the confiscated works were sold abroad. Such resistance was not tolerated and some of them lost their jobs. Over a 100 works were seized from the Munich collections, and comparable numbers from museums elsewhere. (12)

The Degenerate Art Exhibition

The Degenerate Art Exhibition organized by Adolf Ziegler and the Nazi Party in Munich took place between 19th July to 30th November 1937. The exhibition presented 650 works of art, confiscated from German museums. The day before the exhibition started, Hitler delivered a speech declaring "merciless war" on cultural disintegration. Degenerate art was defined as works that "insult German feeling, or destroy or confuse natural form or simply reveal an absence of adequate manual and artistic skill". Whereas these artists are "men who are nearer to animals than to humans, children who, if they lived so, would virtually have to be regarded as curses of God." (13)

Ziegler made a speech at the opening of the exhibition. "Our patience with all those who have not been able to fall in line with National Socialist reconstructions during the last four years is at an end. The German people will judge them. We are not scared. The people trust, as in all things, the judgment of one man, our Führer. He knows which way German art must go in order to fulfil its task as the expression of German character... What you are seeing here are the crippled products of madness, impertinence, and lack of talent... I would need several freight trains clear our galleries of this rubbish... This will happen soon." (14)

The exhibition included paintings, sculptures and prints by 112 artists. This included work by Kathe Kollwitz, George Grosz, Otto Dix, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Erich Heckel, Paul Klee, Karl Schmidt-Rottluff, Max Beckmann, Christian Rohlfs, Oskar Kokoschka, Lyonel Feininger, Ernst Barlach, Otto Müller, Karl Hofer, Max Pechstein, Lovis Corinth, Georg Kolbe, Wilhelm Lehmbruck, Franz Marc, Emil Nolde, Willi Baumeister, Kurt Schwitters, Pablo Picasso, Jean Metzinger, Albert Gleizes, Piet Mondrian, Marc Chagall and Wassily Kandinsky.

The exhibition cleverly manipulated visitors to loathe and ridicule the art on show. As Nausikaä El-Mecky has pointed out: "The shock-value was enhanced by only allowing over-18s into the exhibition. The lines for the Degenerate Art Exhibition went around the block. Inside, many pictures had been taken out of their frames, and were attached to walls that were emblazoned with outraged slogans. Rather than whispering respectfully, people pointed and snickered. The paintings and sculptures had lost their status as artworks, and were now reduced to dangerous and outrageous rubbish." (15)

Visitors found that the works of art were "deliberately badly displayed, hung at odd angles, poorly lit, and jammed up together on the walls, higgledy-piggledy". They carried titles such as Farmers Seen by Jews, Insult to German Womanhood, and Mockery of God. "They were intended to express a congruity between the art produced by mental asylum inmates... and the distorted perspectives adopted by the Cubists and their ilk, a point made explicit in much of the propaganda surrounding the assault on degenerate art as the product of degenerate human beings." (16)

The objective was to "reveal the philosophical, political, racial and moral goals and intentions behind this movement, and the driving forces of corruption which follow them". The Nazis claimed that degenerate art was the product of Jews and Bolsheviks, although only six of the artists featured in the exhibition were actually Jewish. Jonathan Petropoulos, the author of Artists Under Hitler: Collaboration and Survival in Nazi Germany (2014) has pointed out that works were included "if they were abstract or expressionistic, but also in certain cases if the work was by a Jewish artist... The pictures were hung askew, there was graffiti on the walls, which insulted the art and the artists, and made claims that made this art seem outlandish, ridiculous." (17) One of the visitors commented: "The artists ought to be tied up next to their pictures, so that every German can spit in their faces - but not only the artists, also the museum directors who, at a time of mass unemployment, poured vast sums into the ever-open jaws of the perpetrators of these atrocities." (18)

The exhibition drew 2,009,899 visitors. After the exhibition closed, the work was confiscated. Among those who suffered included Emil Nolde (1,052), Erich Heckel (729), Karl Schmidt-Rottluff (688), Ernst Ludwig Kirchner (639), Max Beckmann (509), Christian Rohlfs (418), Oskar Kokoschka (417), Lyonel Feininger (378), Ernst Barlach (381), Otto Müller (357), Karl Hofer (313), Max Pechstein (326), Lovis Corinth (295), George Grosz (285), Otto Dix (260), Franz Marc (130), Paul Klee (102), Paula Modersohn-Becker (70) and Kathe Kollwitz (31). The campaign against "degenerate art" took in work by 1,400 artists in all. (19)

Joseph Goebbels suggested that the government should "make money from the garbage". Hildebrand Gurlitt, an art dealer with international connections was asked to sell this "degenerate art" in order to acquire desperately needed foreign currency. (20) "The inventory reveals how this cynical process unfolded: they were sold through art dealers trusted by the regime, or they could be exchanged for the kind of racially appropriate artworks displayed in the German Art Exhibition... Artworks which could not be liquidated in this manner were simply destroyed. In March 1939, the Propaganda Ministry had around 5,000 artworks burned in the courtyard of the Berlin Main Fire Department." (21)

In 2011 the German police became suspicious of the business activities of Cornelius Gurlitt and raided his flat in Schwabing in spring 2011. Police discovered a vast collection of masterpieces by some of the world's greatest artists. These paintings had been left to him by his father, Hildebrand Gurlitt, who had been killed in a car crash in 1956. It would seem that most of these were the paintings that had not been sold after the Degenerate Art Exhibition or had been stolen from Jewish collectors. His personal collection of over 1,500 items, including works by Otto Dix, Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Paul Cézanne, Paul Gauguin, Henri Matisse, Eugène Delacroix, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Franz Marc, Marc Chagall, Édouard Manet, Camille Pissarro, Auguste Rodin, Edvard Munch, Gustave Courbet, Max Liebermann, Wassily Kandinsky and Paul Klee. (22)

Primary Sources

(1) Paul Schultze-Naumburg, The Struggle for Art (1932)

It is often said that every genuine art reflects the people that originates and sustains it. Obviously, each artist can capture, through his mirror, only a specific part of the character of his people. And yet, it is completely unthinkable that art can live a life of its own and that the beings that appear in front of our eyes are not a true representation of the beings that physically represent a people in the flesh. We know that, from the works of art that the peoples and the times have left us, we can draw a picture of their true spiritual essence, form and environment...

The individual personalities of the artists are too different to reach full overlap. There are those that are tightly oriented to the model and their environment and reproduce it faithfully on the canvas, and those who can only give shape to their dreams of that reality. It does not matter if art is an accurate representation of reality – like it has always been the task of the fine arts - or if it reflects only the times from a spiritual point of view, as a perceptible expression of the substance of reality. After all, one cannot ignore that the higher task of the artist is to show the final objectives to the people of their time, to make visible the image towards which one wishes to move, so that all people could recognize beauty and can start the contest to imitate it and to make themselves compliant with that ideal...

Woman has probably never been depicted so disrespectfully and in so unappetizing a way as in the paintings we have been obliged to put up with in German exhibits of the last twelve years, paintings that inspire only nausea and distrust. They convey not the slightest trace of the sacredness of the human body or of the glory of a divine nakedness. They express a ravening lasciviousness that sees the nude only as an undressed human being in its lowest form...

We often come across with the opinion that art can produce so many pleasures, introducing the beauty in life. When it comes instead of the most important questions of life, art would have nothing to say. Who thinks so, is not clear on the concept of art and the scale of the task that it has to play in people's lives. Actually, those who think that artistic activity consists of the fact that one is rich enough to buy a French impressionist, in order to display it with pride to friends, capture a very small and not important piece of the whole. If you want to give a simple and essential meaning to the concept of art, you might say, it is always the expression of man's desire, which is hereby translated into a perceptible form. This putting-in-shape is a creative act, for which the artist forces are necessary. The essential element of art, as we understand it, is therefore to always show a ‘spiritual direction’. And the idea of National Socialism is based on appropriately 'giving direction' to the German people and leading it to salvation. And since that task is substantially conducted with spiritual tools, national socialism cannot ignore the instrument of art.

(2) Nausikaä El-Mecky, Art in Nazi Germany (9th August, 2015)

How do you destroy an artwork? You can hide it, scratch it, tear it, put a slogan over it, burn it, or, as the Nazis did in 1937, simply show it to millions of people.

If you visited Munich in the summer of that year, you could see two spectacular exhibitions that were held only a few hundred meters apart. One was the Great Exhibition of German Art, showcasing recent leading examples of "Aryan" art. The other was the Entartete Kunst (Degenerate Art) Exhibition, which offered a tour through the art that the National Socialist Party had rejected on ideological grounds. It was made up of art that was not considered "Aryan" and offered a last glimpse before these works of art disappeared.

The Entartete Kunst (Degenerate Art) Exhibition cleverly manipulated visitors to loathe and ridicule the art on exhibit, in part by erasing their original meaning. Until shortly before the exhibition, these paintings and sculptures had been displayed at the nation's greatest museums, but now they were the principal performers in a freak show. The shock-value was enhanced by only allowing over-18s into the exhibition. The lines for the Degenerate Art Exhibition went around the block. Inside, many pictures had been taken out of their frames, and were attached to walls that were emblazoned with outraged slogans. Rather than whispering respectfully, people pointed and snickered. The paintings and sculptures had lost their status as artworks, and were now reduced to dangerous and outrageous rubbish.

Visual symbolism was important to the Nazis, and Hitler himself had been a painter, so it is not surprising that they dedicated significant resources promoting their ideals through art. So how was the decision made? How were "degenerate" and "Aryan" artworks selected? If you look at the works of art that were glorified and compare them to those that were attacked by the Nazis, the differences usually seem clear enough; experimental, personal, non-representational art was rejected, whilst conventionally "beautiful," stereotypically heroic art was revered. This seems like an obvious line to be taken by a totalitarian regime: everyone will find these artworks beautiful, and everyone will feel and think the same thing about them, without the risk of unwanted, random, personal, or unclear interpretations.

And the Nazis presented it as a simple decision, any true German would immediately be able to tell the difference. But in reality, a four-year battle was fought all the way to the top echelons of the Nazi hierarchy over what "Aryan" art was supposed to be, exactly. The opinions on this could not have been more contradictory, and top Nazi officials such as Heinrich Himmler, Joseph Goebbels and Alfred Rosenberg championed the art they each preferred.

Surprisingly, before 1937, Goebbels–and many other Nazis–collected modern art. Goebbels had works of modern art in his study, his living room and was a fan of many artists that eventually ended up in the Degenerate Art Exhibition. Heinrich Himmler was interested in mystical, Germanic art that harked back to a tribal past. Another influential Nazi, Alfred Rosenberg, liked the pastoral, romantic style that depicted humble farmers, rural landscapes and blond maidens.Hitler would have none of it. He loathed Expressionism and modern art whilst pastoral idylls were not serious enough. Goebbels reversed himself and became one of the driving forces behind the Degenerate Art Exhibition, prosecuting the same artworks he had once enjoyed. Rosenberg also let go, albeit reluctantly, whilst Himmler changed tack and stole artworks by the wagonload behind Hitler’s back throughout the war.

The Degenerate Art Exhibition mostly exhibited Expressionism, New Objectivism and some abstract art. Strangely, very few works came from Jewish artists, and a lot of artworks had until recently been favorites of many Nazis. Renowned works by artists such as Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Karl Schmidt-Rotluff and Ernst Barlach now hung on walls marked with graffiti. The works ranged from quiet and traditional looking, such as Ernst Barlach’s The Reunion (Das Wiedersehen), 1926 which showed two poised, realistically carved wooden figures holding each other, to more grotesquely painted works, such as Otto Dix’ War Cripples (Kriegskrüppel), 1920. This work shows a procession of cartoonesque yet morbid war veterans, painfully moving forward with the aid of pushchairs, prosthetic legs and crutches, smoking cheerfully, though one soldier’s face is half eaten away, revealing a rictus grin of clenched teeth.

(3) Adolf Ziegler, speech at the opening of the Degenerate Art Exhibition (19th July, 1937)

Our patience with all those who have not been able to fall in line with National Socialist reconstructions during the last four years is at an end. The German people will judge them. We are not scared. The people trust, as in all things, the judgment of one man, our Führer. He knows which way German art must go in order to fulfil its task as the expression of German character... What you are seeing here are the crippled products of madness, impertinence, and lack of talent... I would need several freight trains clear our galleries of this rubbish... This will happen soon.

(4) Völkischer Beobachter (17th July, 1937)

Imbued with the sacred aura of this house and with the historical greatness of this moment, we closed our sublime ceremony with national hymns that resounded like a pledge from the people and its artists to the Führer. At the conclusion of the solemn dedication, the Führer and guests of honour from the diplomatic corps, the government, and the leadership of the NSDAP moved on the large, airy rooms of this new temple of German art to admire the first Great German Art Exhibition.

(5) Ginny Dawe-Woodings, The Political Picture - How the Nazis created a Distinctly Fascist Art (26th September, 2015)

The communication of values and messages by allegory and metaphor was important but high value was also placed on representations of fitness and well being, as characterizing racial purity and superiority, the Aryan ideal. The identification of the naked man with the ideal of classical beauty and heroism was a ubiquitous sentiment in National Socialist art and popular culture....

Within its unique conservative style Nazi art was purposeful, with content chosen less for aesthetic appeal and more for usefulness in the ‘bigger political picture’. It achieved much in terms of embodying and communicating the wider fascist ethos of the NSDAP: reinforcing its back-story of a pure race and a country with both a mystical past and a great future, a ‘thousand-year Reich’, that would be delivered if the people believed in the ‘quasi-religious’ values of Nazism – military and moral strength together with an intolerance of weakness, liberal values and, above all, the evils and degeneracy of communism and Judaism. It is interesting that the art created was so distinct and clear in its message, such a quintessential fascist aesthetic, that almost seventy years later the material is still something of a taboo with many authors putting disclaimers in their work when discussing Nazi art, seeking to avoid condoning the content.

(6) Bruno E. Werner, Deutsche Allgemeine Zeitung (20th July, 1937)

Most of the painting shows the closest possible ties to the Munich school at the turn of the century. Leibl and his circle and, in some cases, Defregger are the major influences on many paintings portraying farmers, farmers' wives, woodcutters, shepherds, etc., and on interiors that lovingly depict many small and charming facets of country life. Then there is an extremely large number of landscapes that also carry on the old traditions.... We also find a rich display of portraits, particularly likenesses of government and party leaders. Although subjects taken from the National Socialist movement are relatively few in number, there is nonetheless a significant group of paintings with symbolic and allegorical themes. The Führer is portrayed as a mounted knight clad in silver armour and carrying a fluttering flag. National awakening is allegorized in a reclining male nude, above which hover inspirational spirits in the form of female nudes. The female nude is strongly represented in this exhibit, which emanates delight in the healthy human body.

(7) Lucy Burns, Degenerate Art: Why Hitler Hated Modernism (2013)

In July 1937, four years after it came to power, the Nazi party put on two art exhibitions in Munich.

The Great German Art Exhibition was designed to show works that Hitler approved of - depicting statuesque blonde nudes along with idealized soldiers and landscapes.

The second exhibition, just down the road, showed the other side of German art - modern, abstract, non-representational - or as the Nazis saw it, "degenerate".

The Degenerate Art Exhibition included works by some of the great international names - Paul Klee, Oskar Kokoschka and Wassily Kandinsky - along with famous German artists of the time such Max Beckmann, Emil Nolde and Georg Grosz.

The exhibition handbook explained that the aim of the show was to "reveal the philosophical, political, racial and moral goals and intentions behind this movement, and the driving forces of corruption which follow them".

Works were included "if they were abstract or expressionistic, but also in certain cases if the work was by a Jewish artist," says Jonathan Petropoulos, professor of European History at Claremont McKenna College and author of several books on art and politics in the Third Reich.

He says the exhibition was laid out with the deliberate intention of encouraging a negative reaction. "The pictures were hung askew, there was graffiti on the walls, which insulted the art and the artists, and made claims that made this art seem outlandish, ridiculous."

British artist Robert Medley went to see the show. "It was enormously crowded and all the pictures hung like some kind of provincial auction room where the things had been simply slapped up on the wall regardless to create the effect that this was worthless stuff," he says.

Hitler had been an artist before he was a politician - but the realistic paintings of buildings and landscapes that he preferred had been dismissed by the art establishment in favour of abstract and modern styles.

So the Degenerate Art Exhibition was his moment to get his revenge. He had made a speech about it that summer, saying "works of art which cannot be understood in themselves but need some pretentious instruction book to justify their existence will never again find their way to the German people".

The Nazis claimed that degenerate art was the product of Jews and Bolsheviks, although only six of the 112 artists featured in the exhibition were actually Jewish.

The art was divided into different rooms by category - art that was blasphemous, art by Jewish or communist artists, art that criticized German soldiers, art that offended the honour of German women.

One room featured entirely abstract paintings, and was labeled"the insanity room".

"In the paintings and drawings of this chamber of horrors there is no telling what was in the sick brains of those who wielded the brush or the pencil," reads the entry in the exhibition handbook.

The idea of the exhibition was not just to mock modern art, but to encourage the viewers to see it as a symptom of an evil plot against the German people.

The curators went to some lengths to get the message across, hiring actors to mingle with the crowds and criticize the exhibits.

The Degenerate Art Exhibition in Munich attracted more than a million visitors - three times more than the officially sanctioned Great German Art Exhibition.

Some realized it could be their last chance to see this kind of art in Germany, while others endorsed Hitler's views. Many people also came because of the air of scandal around the show - and it wasn't just Nazi sympathizers who found the art off-putting.

(8) MIchael Glover, The Independent (7th November, 2017)

What was Hitler's view of art? Even today, to be reading Mein Kampf on the upper deck of a clean and orderly public train one dark November night in Germany, feels a little staining, as if one's very finger ends might just turn an accusatory yellow. Should it have been wrapped in plain brown parcel paper in order to avoid any stranger's eye connecting with that malign, gilded swastika on the front cover? And then there are Hitler's words themselves, written by a man imprisoned in the fortress of Landsberg am Lech in 1924, nine years before he came to power, all six hundred pages of them, pent, furious, illogical. What could have motivated Hitler's level of hysteria? The total collapse of Germany. What could have brought his country to its knees?

This month a sensational story about art, the Nazis and a part-concealed Jewish identity, stutters to a fascinatingly inconclusive conclusion in Germany with the opening of two exhibitions, one in Bonn and the other in Bern. The story began in 2012 when an old man called Cornelius Gurlitt was accused of tax evasion by the authorities in Augsburg. That accusation led to the discovery of an extraordinary trove of art in his apartment in a very respectable part of Munich. For months the authorities kept the story to themselves. Then the press got wind of it. Those months of concealment gave the story of its discovery by the authorities some head wind.

The art had belonged to his father Hildebrand, who had been a museum director and art dealer from the time of the Weimar Republic in the 1920s, and throughout the Third Reich and on. Hildebrand had died in a car accident in 1956. It was presented as nothing less than the story of the wheelings and dealings of Hitler's principal art dealer – and here was the loot perhaps, in the custody of his 80-year-old, reclusive son, in the full dazzle of publicity.

The two exhibitions put on display 400 of the 1500 works in the Gurlitt collection, 250 in Bonn and 150 in Bern. They also tell the immensely complicated story of that seizure and its subsequent impact, demonstrate how the provenance experts of Germany and Switzerland responded to its shock waves, and show off some of its best works by such modern masters as Klee, Munch, Dix, Marc, Nolde. And, most interesting of all, they present in great detail the convoluted, morally dubious story of Hildebrand Gurlitt himself within the context of the tumultuous times through which he lived.

Yes, it was one respectable man's fear of the consequence of having been condemned as a Mischling (a man of mixed race, one quarter Jew) and sent to the camps, which caused the Dresden art dealer and museum director Hildebrand Gurlitt to work with the Reich Ministry in order to save his own skin. A Nuremberg Law of 1935 had characterised – and therefore condemned – him as a 'second-degree half-caste'. He was a vulnerable man, aware of the pressing need to survive in an ever more dangerous world. The only answer was to cosy up to the regime. He therefore perjured himself by dealing in and disposing of works which Hitler condemned as degenerate, which were snatched in their thousands from public museums, and looted from the homes of Jewish collectors. More than 20,000 works were confiscated in all. "We even hope to make money from the garbage," quipped Goebbels.

That is why the works on these walls were so dangerous, because they had the power, in Hitler's opinion, to deprave the human spirit. Do all these works have something in common then to our eye now? Yes, undeniably. They show off what we might loosely describe as the free flow of the human spirit. Hitler believed that art should be elevating, noble, in tune with the aristocratic principle. The classical and the realistic, in a world shown to be settled, orderly and steady, were his ideals. The art here is, by comparison, full of bodily distortion. It is wild, impulsively improvisatory, dangerously subjective, stylistically lawless and untameable. It knows no expressive boundaries. You could even call much of it pessimistic – or even schizophrenic. Did not Jung describe the works of Picasso as pathological in 1932?

Hildebrand Gurlitt himself was a tissue of contradictions, an opportunist. Before and after the Second World War, he had championed the cause of modern art that he was complicit in denouncing during the years of the Reich. He was to champion it yet again after the war. And yet even as he denounced it, he was also dealing in it to his own financial advantage. In the 1920s, as a successful museum director in the Weimar Republic, he had put on shows of work by the moderns, arguing that it was the new work by such painters as Beckman which would serve 'as a bait for everything spiritual', as he put it. He wanted avant-garde art to play its part in bringing about a social revolution. He was a German cultural idealist. Like Hitler, he wanted to re-build the reputation of Germany as a nation of culture.

Later on these works were seized wholesale by the Nazis, and many artists suffered brutally as a consequence. They went into exile. They committed suicide. They hid themselves away, consumed by an inner darkness. Many of their tragic human stories are told here. Emil Nolde had 1,052 works seized from German museums. He protested with great violence. Others protested on his behalf. Was his work not the very epitome of Germanness? It was all to no avail. He withdrew to his studio in North Germany and, living in isolation, devoted himself to painting 1,300 watercolours on very small sheets of paper. He described these works as his 'unpainted paintings'.

Hildebrand Gurlitt's skills as an art dealer with international connections were extremely useful. The Reich desperately needed foreign currency to fund the war effort. Hildebrand bought, sold, and acquired work for German museums and other collectors, and amassed works for his own private collection, enriching himself in the process. He became Hitler's art dealer. And after the war, under close scrutiny at the denazification tribunal, he slipped through the net that appeared to be closing around him by characterising himself as a victim. And, what is more, he kept much of what he had acquired.

(9) Philip Oltermann, The Guardian (4th November, 2013)

About 1,500 modernist masterpieces – thought to have been looted by the Nazis – have been confiscated from the flat of an 80-year-old man from Munich, in what is being described as the biggest artistic find of the postwar era.

The artworks, which could be worth as much as €1bn (£860m), are said to include pieces by Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, Marc Chagall, Paul Klee, Max Beckmann and Emil Nolde. They had been considered lost until now, according to a report in the German news weekly Focus.

The works, which would originally have been confiscated as "degenerate art" by the Nazis or taken from Jewish collectors in the 1930s and 1940s, had made their way into the hands of a German art collector, Hildebrand Gurlitt. When Gurlitt died, the artworks were passed down to his son, Cornelius – all without the knowledge of the authorities.

Gurlitt, who had not previously been on the radar of the police, attracted the attention of the customs authorities only after a random cash check during a train journey from Switzerland to Munich in 2010, according to Focus. Further police investigations led to a raid on Gurlitt's flat in Schwabing in spring 2011. Police discovered a vast collection of masterpieces by some of the world's greatest artists.

The artworks are thought to have been stored amid juice cartons and tins of food on homemade shelves in a darkened room. Since their seizure, they have been stored in a safe customs building outside Munich, where the art historian Meike Hoffmann, from Berlin university, has been assessing their precise origin and value. When contacted by the Guardian, Hoffmann said she was under an obligation to maintain secrecy and would not be able to comment on the Focus report until Monday.

According to Focus, Cornelius Gurlitt, described as a loner, may have kept himself in pocket over the years by occasionally selling the odd artwork. Several of the frames in the flat were empty. He is thought to have sold at least one picture – a painting called Lion Tamer by Beckmann – since his flat was first raided by the police. On 2 December 2011, the painting was sold for €864,000 at an auction house in Cologne.

At least 300 paintings in the collection are thought to belong to a body of about 16,000 works once declared "degenerate art". Others are suspected to have been owned by fleeing Jewish collectors who had to leave belongings behind.

One Matisse painting used to belong to a French art dealer, Paul Rosenberg, whose granddaughter is Anne Sinclair, the TV journalist who is also the ex-wife of the former managing director of the International Monetary Fund Dominique Strauss-Kahn. Rosenberg was renowned for representing Picasso, Georges Braque and Matisse.

Sinclair and her family have been campaigning for the return of looted Nazi treasures for years. "We are not willing to forget, or let it go," Marianne Rosenberg, another granddaughter, told the New York Times in April. "I think of it as a crusade."

Gwendolen Webster, an art historian who has spent time studying works from the Nazis' "degenerate art" collection, told the Guardian the significance of the find was "absolutely staggering for historians" but opened a legal can of worms.

One of the reasons why German customs may have been sitting on their find for such a long time is that they can expect a huge number of claims for restitution from around the world, with all the diplomatic difficulties that entails.

Descendants of Jewish collectors who were blackmailed or simply robbed of their works by the Nazis may now be able to legally claim ownership of some of the works in Munich.

The looted art trove may help to shed light on one of the more obscure chapters in Nazi Germany's history. Modernist art was banned soon after the Nazis came to power, on the ground that it was "un-German" or Jewish Bolshevist in nature.

From spring 1933 right up to the start of the war, exhibitions of the art toured the country, showcasing works that are now considered classics of expressionism, surrealism, cubism and Dada. Records of which artworks the authorities had looted from where are incomplete. "It was complete anarchy," says Webster.

Hildebrand Gurlitt, who had been a museum director in Zwickau until Hitler came to power, lost his post because he was half Jewish, but was later commissioned by the Nazis to sell works abroad. The discovered loot may show that Gurlitt in fact collected many of the artworks himself and managed to keep them throughout the war.

After the war, allied troops designated Gurlitt a victim of Nazi crimes. He reportedly said he had helped many Jewish Germans to fund their flight into exile, and that his entire art collection had been destroyed in the bombing of Dresden.

(10) Kate Connolly, The Guardian (27th October, 2017)

Hundreds of works of art that were hoarded by the son of a Nazi art dealer will go on public display for the first time in decades in joint exhibitions in Germany and Switzerland opening next week.

Kunstmuseum Bern and the Bundeskunsthalle in Bonn will present the works found in the homes of Cornelius Gurlitt in two parallel shows called Gurlitt Status Report that are expected to draw art lovers from around the world.

Around 1,500 works, including pieces by Claude Monet, Paul Cézanne, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Otto Dix and Gustave Courbet, worth hundreds of millions of euros were discovered in Gurlitt’s Munich and Salzburg residences by tax inspectors and revealed in 2013, in what was described as the biggest artistic find of the postwar era.

Gurlitt, an art-loving recluse who inherited his father’s collection, died of heart failure aged 81 the following year, having bequeathed the works to the Bern museum. A Munich court paved the way for the groundbreaking exhibitions to go ahead after ruling against a claim made by a family member that Gurlitt had not been of sound mind when he made the bequest.

“For the first time the public will be given an insight into these works of art that have been talked about in the news so much as a sensational find and a treasure trove,” said Nina Zimmer, who has curated the Bern exhibition.

It is also an opportunity to look at why the art world has so far undergone little critical self-appraisal about its role during the Nazi era. Switzerland’s controversial role as a hub in the profitable field of Nazi-confiscated art is also under scrutiny.

Bern’s exhibition will tell the story of modern art, which was outlawed by the Nazis under the “degenerate art action” of 1937 and 1938, which led to the confiscation of more than 23,000 paintings, sculptures and prints from public galleries across Germany. Many of the works were sold on abroad to make money for the Nazi regime.

The Bundeskunsthalle will simultaneously present the story of looted art – works which were stolen, by theft or sales under pressure, from Jewish individuals or families and others persecuted by the Nazis.

It will particularly touch upon the darkest chapter of the biography of Cornelius Gurlitt’s father, Hildebrand, who acted as one of the most important art dealers in the Third Reich, working directly on behalf of the Nazi leader, Adolf Hitler.

Zimmer said the exhibitions were about “paying homage to the people who became victims of the National Socialist art theft, as well as to the artists who were defamed and persecuted by the regime as degenerate”...

Before colluding with the Nazis, Hildebrand Gurlitt had started his career as a “brilliant, young and progressive” museum director in Zwickau, said Zimmer, where he tried to convince people of the merits of modern art in the 1920s. But he faced a rightwing backlash and was pushed from his position.

In 1933 he moved to Hamburg, where he continued in a similarly progressive vein as the Nazis rose to power. When he refused to raise the swastika flag at his gallery, he was fired for a second time.

Hildebrand Gurlitt moved into dealing in modern art and opened a commercial gallery, which he was forced to register in his wife’s name because of his Jewish heritage.

It was then that he started to actively align himself with the Nazi system, writing to the propaganda ministry to volunteer his skills as a leading expert in modern – ergo “degenerate” art – and was chosen as one of four dealers to act for the Nazis, stationed in Paris, with the particular task of acquiring works for the unrealised Führermuseum project in Linz....

The five works that have so far been returned to the heirs of their former owners include Henri Matisse’s Seated Woman, Max Liebermann’s Riders on the Beach, Interior of a Gothic Church by Adolf von Menzel and Camille Pissarro’s The Seine and the Louvre.

The provenance of others still under investigation include works by Edvard Munch, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Auguste Rodin and Paul Signac.

Arguably the best piece in the collection, Cézanne’s La Montagne Sainte Victoire, which was found in Gurlitt’s Salzburg home behind a cupboard, continues to be the subject of a legal dispute in which the Cézanne family is arguing for its return.

Zimmer said it was doubtful whether such a spectacular find of art gathered in the Nazi era would ever be found again “simply because Hildebrand Gurlitt was the fourth Nazi dealer – and there is no fifth one,” she said.