Lionel "Buster" Crabb

Lionel (Buster) Crabb, the son of Hugh Alexander Crabb and his wife, Beatrice Goodall, was born in Streatham, London, on 28th January 1909. His father was a commercial traveller for a firm of photographic merchants. According to his biographer, Richard Compton-Hall, "little is known about Crabby or Buster Crabb's early life save that it was modestly commercial." (1)

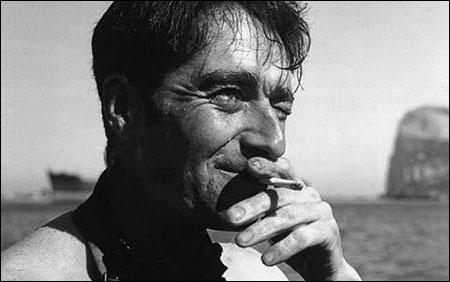

Lionel Crabb earned his nickname from the Hollywood actor, athlete and pin-up Buster Crabbe, who had played Flash Gordon in the film series and won a gold medal for swimming at the 1932 Olympic Games. "In almost every way, the English Buster Crabb was entirely unlike his namesake, being English, tiny, and a poor swimmer (without flippers, he could barely complete three lengths of a swimming pool). With his long nose, bright eyes and miniature frame, he might have been an aquatic garden gnome." (2)

Buster Crabb - Frogman

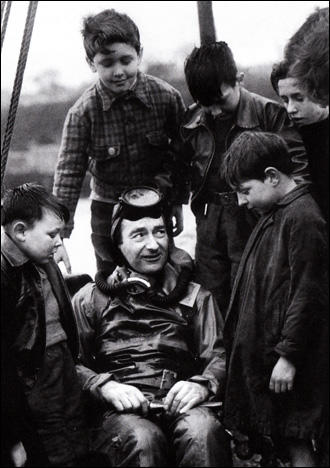

He worked in a variety of jobs and eventually joined the Merchant Navy. On the outbreak of the Second World War he transferred to the Royal Navy where he was trained as a diver. In 1940 he volunteered for bomb disposal duties. In 1942 he was sent to Gibraltar, to take part in the underwater battle around the Rock, where Italian frogmen, using rnanned torpedoes and limpet mines, were sinking thousands of tons of Allied shipping. Crabb and his fellow divers set out to stop them, with remarkable success, blowing up enemy divers with depth charges, intercepting torpedoes and peeling mines off the hulls of ships. "Despite his nickname, Commander Lionel Kenneth ("Buster") Crabb was no great shakes as a surface swimmer; but given a pair of rubber flippers, some goggles and an oxygen tank, he was at home in the murky depths. In 1942 when Italian divers were busily attaching lethal limpet mines to the bottoms of Royal Navy ships at anchor off Gibraltar, Buster Crabb was even busier at the far more dangerous job of removing them." (3) Nicholas Elliott worked with Crabb during the war, and considered him "a most engaging man of the highest integrity... as well as being the best frogman in the country, probably in the world". (4)

In 1945 Crabb cleared mines from the ports of Venice and Livorno, and when the militant Zionist group Irgun began attacking British ships with underwater explosives, he was called in to defuse them. This was an extremely dangerous job, but Crabb survived and in 1947 awarded the George Medal for "undaunted devotion to duty" and the OBE. Crabb also investigated a suitable discharge site for a pipe from the atomic weapons station at Aldermaston. Crabbe later returned to the Royal Navy and after helping rescue men trapped in a submarine, and was promoted to the rank of commander in 1952. Buster Crabb married Margaret Elaine on 15th March 1952. The couple separated in 1953.

In March 1955 Buster Crabb was forced to leave the navy on age grounds. According to Ben Macintyre: "He cut a remarkable figure in civilian life, wearing beige tweeds, a monocle and a pork pie hat, and carrying a Spanish swordstick with a silver knob carved into the shape of a crab. But there was another, darker side... Crabb suffered from deep depressions, and had a weakness for gambling, alcohol and barmaids. When taking a woman out to dinner he liked to dress up in his frogman outfit; unsurprisingly, this seldom had the desired effect, and his emotional life was a mess. In 1956 he was in the process of getting divorced after a marriage that had lasted only a few months. He worked, variously, as a model, undertaker and art salesman, but like many men who had seen vivid wartime action, he found peace a pallid disappointment. (5)

Visit of Nikita Khrushchev

In April 1956, the Soviet leaders, Nikita Khrushchev and Nikolai Bulganin paid a visit on the battleship Ordzhonikidz, docking at Portsmouth. The visit was designed to improve Anglo-Soviet relations. Sir Anthony Eden, the prime minister, who had high hopes of establishing better relations and moderating the Cold War issued a precise directive to all services banning any intelligence operation of any kind against the Soviet leaders and the ship. (6)

The MI6 London station - run by Nicholas Elliott - decided that the visit was too good an opportunity to miss and ten days beforehand put up a list of six operations to MI6's Foreign Office adviser. "The Admiralty had been particularly keen to understand the underwater-noise characteristics of the Soviet vessels. The placing of a Foreign Office adviser inside MI6 was part of a drive to put the service on a somewhat tighter leash, but when an MI6 officer ambled into his office for a ten-minute chat about the plans, the adviser came away thinking they would then be cleared at a higher level (as some sensitive operations were) while Elliott and his colleagues assumed that the quick conversation constituted clearance." (7) When Eden heard about it he told MI6: "I am sorry, but we cannot do anything of this kind on this occasion." Elliott would later insist that the "operation was mounted after receiving a written assurance of the Navy's interest and in the firm belief that government clearance had been given". (8) Elliott also argued: "We don't have a chain of command. We work like a club." (9)

MI5 decided to bug the rooms at Claridge's Hotel that had been taken over by the Soviet delegation. The operation was a failure: "We listened to Khrushchev for hours at a time, hoping for pearls to drop. But there were no clues to the last days of Stalin, or to the fate of the KGB henchman Beria. Instead, there were long monologues from Khrushchev addressed to his valet on the subject of his attire. He was an extraordinary vain man. He stood in front of the mirror preening himself four hours at a time, and fussing with his hair parting." (10)

Death of Buster Crabb

On 16th April 1956, the day before the cruiser was due to arrive, Crabb and Bernard Smith, his MI6 minder, arrived in Portsmouth and registered with a local hotel. Against the rules of the SIS both men signed in their real names. Contrary to the fundamental rules of diving, that evening Crabb drank at least five double whiskys. By daybreak, the toxicity in his blood remained fatally high. (11)

The following morning Crabb dived into Portsmouth Harbour. "The main task was to swim underneath the Soviet cruiser Ordzhonikidze, explore and photograph her keel, propellers and rudder, and then return. It would be a long, cold swim, alone, in extremely cold and dirty water, with almost zero visibility at a depth of about thirty feet. The job might have daunted a much younger and healthier man. For a forty seven-year-old, unfit, chain-smoking depressive, who had been extremely drunk a few hours earlier, it was close to suicidal." (12) However, Elliott insisted that "Crabb was still the most experienced frogman in England, and totally trustworthy ... He begged to do the job for patriotic as well as personal motives." (13) Peter Wright, who worked for MI5 said that it was a typical piece of MI6 adventurism, ill-conceived and badly executed." (14)

Gordon Corera, the author of The Art of Betrayal (2011) has pointed out: "Where Bond battled the bad guys in the crystal-clear Caribbean, the diminutive Crabb plunged into the cold, muddy tide of Portsmouth Harbour just before seven in the morning. He had about ninety minutes of air and by 9.15 it was clear something had gone wrong. For a while, it looked like the whole affair might be hushed up. The MI6 officer went back to the hotel to rip out the registration page. The hotel owner went to the press, who sniffed a good story. The disappearance of a well-known hero could not be covered up." (15)

That night, James Thomas, the First Lord of the Admiralty, was dining with some of the Soviet visitors, one of whom asked, "What was that frogman doing off our bows this morning". According to the Russian, Crabb had been seen swimming at the surface at 7.30 a.m. by a Soviet sailor. (16) The commander-in-chief Portsmouth, denying knowledge of any frogman, assured the Russian there would be an Inquiry and hoped that all discussion had been terminated. With the help of the intelligence services, the Admiralty attempted to cover up the attempt to spy on the Russian ship. On 29th April the Admiralty announced that Crabb went missing after taking part in trials of underwater apparatus in Stokes Bay (a place five kilometres from Portsmouth).

The Soviet government now issued a statement announcing that a frogman was seen near the cruiser Ordzhonikidze on 19th April. This resulted in newspapers publishing stories claiming that Crabb had been captured and taken to the Soviet Union. Time Magazine reported: "... soon after anchoring, the Ordzhonikidze had taken the precaution of putting a crew of its own frogmen over the side. Had the Russian frogmen met their British counterpart in the quiet deep? Had Buster Crabb been killed then and there, or kidnapped and carried off to Russia? At week's end, the mystery of Frogman Crabb's fate remained as deep and impenetrable as the waters that surrounded so much of his life." (17) Nicholas Elliott claimed that he knew how Crabb died: "He almost certainly died of respiratory trouble, being a heavy smoker and not in the best of health, or conceivably because some fault had developed in his equipment." (18)

Sir Anthony Eden, the British prime minister was furious when he discovered about the MI6 operation that had taken place without his permission. Eden pointed out in the House of Commons: "I think it is necessary, in the special circumstances of this case, to make it clear that what was done was done without the authority or knowledge of Her Majesty's Ministers. Appropriate disciplinary steps are being taken." (19) Ten days later, Eden made another statement making it clear that his explicit instructions had been disobeyed. (20)

Eden forced the Diretor-General of MI6, Major-General John Sinclair, to take early retirement. He was replaced by Sir Dick White, the head of MI5. As MI5 was considered by MI6 to be an inferior intelligence service, this was the severest punishment that could be inflicted on the organization. George Kennedy Young, a senior figure in MI6 defended the actions of Elliott. He argued that in "a world of increasing lawlessness, cruelty and corruption... it is the spy who has been called upon to remedy the situation created by the deficiencies of ministers, diplomats, generals and priests.. these days the spy finds himself the main guardian of intellectual integrity." (21)

On 9th June 1957, a headless body in a frogman suit was discovered floating off Pilsey Island. As the hands were also missing it was impossible to identify it as being that of Lionel Crabb. His former wife inspected the body and was unsure if it was Crabb. Pat Rose, his girlfriend, claimed it was not him but another friend, Sydney Knowles, said that Crabb, like the dead body, had a scar on the left knee. The coroner recorded an open verdict but announced that he was satisfied the remains were those of Crabb.

In 1960 J. Bernard Hutton published his book Frogman Spy. Hutton argues that his sources claim that Crabb had been captured alive during his espionage activities and had been smuggled back to Soviet Union for torture and interrogation. According to Russian documents that Hutton had seen, Crabb later served as a diving officer in the Russian Navy. To help conceal the fate of Crabb, the Soviets dropped a headless and handless body wearing Crabb's equipment in the water near where he was lost a year earlier.

Tim Binding wrote a fictionalized account of Crabb's life, Man Overboard. Published in 2005, Binding novel is based on the story that appeared in Frogman Spy. Soon afterwards Binding was contacted by Sydney Knowles, the man who had originally identified Crabb's body. Knowles told Binding that Crabb was murdered by MI5 when it was discovered that he intended to defect to the Soviet Union. According to Knowles, Crabb was instructed to carry out a spying operation on the Ordzhonikidze. Crabb was supplied with a new diving partner who killed him during the mission. Knowles alleges that he was ordered by MI5 to identify the body, when he knew it was definitely not Crabb. Binding published this information in an article in The Mail on Sunday on 26th March, 2006.

In November, 2007, Eduard Koltsov, a former Soviet frogman, gave an interview where he claimed that he killed Crabb. It was argued that a tip-off from a British spy (probably Kim Philby) meant that he had been lying in wait. (22) According to Gordon Corera, the author of The Art of Betrayal (2011): "Fearing that Crabb was planting a mine to blow up the ship, the frogman says he swam up from below to slash Crabb's air tubes and then his throat with a knife. The body was so small he at first thought it belonged to a boy. But he then found himself staring into the dying eyes of a middle-aged man. According to his unconfirmed account, he pushed the body away into the undercurrents, leaving a trail of blood." (23)

Primary Sources

(1) Ben Macintyre, A Spy Among Friends (2014)

In the distance, through the drifting mist, loomed the faint shapes of three Soviet warships, newly arrived in Britain on a goodwill mission and berthed alongside the Southern Railway jetty. An oarsman rowed the boat out some eighty yards offshore. Crabb adjusted his air tank, picked up a new experimental camera issued by the Admiralty Research Department, and extinguished the last of the cigarettes he had smoked continuously since waking. His task was to swim underneath the Soviet cruiser Ordzhonikidze, explore and photograph her keel, propellers and rudder, and then return. It would be a long, cold swim, alone, in extremely cold and dirty water, with almost zero visibility at a depth of about thirty feet. The job might have daunted a much younger and healthier man. For a forty seven-year-old, unfit, chain-smoking depressive, who had been extremely drunk a few hours earlier, it was close to suicidal.

The mission, codenamed "Operation Claret", bore all the hallmarks of a Nicholas Elliott escapade: it was daring, imaginative, unconventional and completely unauthorised.

(2) Time Magazine (14th May, 1956)

What happened to the frogman? All over Britain the question was being asked last week, but the answer was shrouded in a watery mystery that suggested a Jules Verne fantasy rewritten by Eric Ambler.

Despite his nickname, Commander Lionel Kenneth ("Buster") Crabb was no great shakes as a surface swimmer; but given a pair of rubber flippers, some goggles and an oxygen tank, he was at home in the murky depths. In 1942 when Italian divers were busily attaching lethal limpet mines to the bottoms of Royal Navy ships at anchor off Gibraltar, Buster Crabb was even busier at the far more dangerous job of removing them. Mustered out of the navy at war's end with the George Medal for heroism, Crabb returned to civilian life as a salesman.

Three weeks ago Frogman Crabb was once again plying his old trade in Britain's home waters, but no one, or practically no one, knew it until last week when, after an admitted delay of ten days, the British Admiralty announced tersely that Commander Crabb was "missing and presumed drowned." What had happened? All the Admiralty would say in amplification was that Frogman Crabb had been called back for special assignment and was "employed in connection with trials of certain underwater apparatus."

Buster Crabb and an unidentified male companion had checked into Portsmouth's Sally Port Hotel on April 17. On the following day, the Russian cruiser Ordzhonikidze steamed into Portsmouth harbor bearing Visitors Khrushchev and Bulganin. Crabb was absent from his hotel room all that day. The next day he checked out and was never seen again. The day before the announcement of his disappearance, operatives from Britain's top-secret Criminal Investigation Division tore all records of his stay out of the hotel register. If Portsmouth's police were hunting for clues, they were not admitting it. "Our inquiries," they said, "are governed by the Official Secrets Act."

The Russians themselves were less reticent but only slightly more informative. "A watchman on our ship saw the frogman come to the surface in Portsmouth harbor," said an assistant naval attachè at the Soviet embassy, but "we were in a British port and there was nothing we could do." It was nevertheless true that soon after anchoring, the Ordzhonikidze had taken the precaution of putting a crew of its own frogmen over the side.

Had the Russian frogmen met their British counterpart in the quiet deep? Had Buster Crabb been killed then and there, or kidnapped and carried off to Russia? At week's end, the mystery of Frogman Crabb's fate remained as deep and impenetrable as the waters that surrounded so much of his life.

(3) Time Magazine (14th May, 1956)

Is Britain's frogman dead? The Admiralty said it thought he was. If he died in some underwater accident, what became of his body? Why had the Admiralty waited ten days before saying anything?

Had the frogman been spying on the Soviet cruiser and destroyers lying in Portsmouth harbor? What could he see underwater if he had been spying? Had the Russians (who brought Bulganin and Khrushchev to England) caught the frogman and quietly taken him prisoner? Had they done him in, or had they dumped his body at sea to save embarrassment?

Furor at Home. Last week the fate of Frogman Lionel ("Buster") Crabb, wartime hero in the Royal Navy, was giving Prime Minister Sir Anthony Eden one of the most awkward times of his political career. In the House of Commons, Sir Anthony tried to dismiss the whole matter: "It would not be in the public interest to disclose the circumstances in which Commander Crabb is presumed to have met his death." But then he added mysteriously: "I think it necessary, in the special circumstances of this case, to make it clear that what was done was done without the authority or the knowledge of Her Majesty's Ministers. Appropriate disciplinary steps are being taken."

His evasion did not dispel curiosity; it doubled it. The obvious inference was that Commander Crabb had been employed by some secret arm of the government. Whatever the intelligence agency hoped to learn under the Soviet cruiser Ordzhonikidze was plainly not worth the risk of being caught at it. The furor swelled. Britain's Labor leaders had a special reason for pressing the attack. They were embarrassed by rank-and-file criticism that they had been unmannerly to B. & K. at the famous dinner party and were anxious to convict Sir Anthony of even cruder mistreatment of his guests. They threatened a motion to cut Eden's salary - a formal method of bringing a Minister's personal competence into question.

At this point the Russians got crudely into the act.

Moscow radio announced that the Kremlin had sent an official note to Whitehall concerning what Pravda called this "shameful espionage." With a lack of diplomatic good manners, the Russians went on to quote their protest and the British reply.

This was their story: Russian seamen had spotted the frogman, wearing a black diving suit and flippers on his feet, at 7:30 one morning, floating between two Soviet destroyers. He stayed on the surface a minute or two. then dived under. The Russian admiral complained to the Portsmouth naval base commander, a rear admiral, who "categorically denied the possibility" of a British frogman in the area. "In actual fact," said Moscow, Crabb's secret activities have since been confirmed. The Foreign Office answer was a model of stiff-lipped embarrassment: "Commander Crabb carried out frogman tests, and, as is assumed, lost his life during these tests. His presence in the vicinity of the destroyers occurred without any permission whatever, and Her Majesty's Government express their regret at the incident."

This, while not very edifying, was more informative than Eden had been in the House of Commons. Anthony Eden had more explaining to do.

(4) Tom Bower, The Perfect English Spy (1995)

On the 17th, Crabb commenced his first dive and then surfaced near the Russian cruiser. After resubmerging, he returned to the shore for some adjustments and dived again. He did not return. Smith raised the alarm in London and at that stage White was alerted. The eyewitness to that moment is Peter Wright, whose version was broadly confirmed by White: "We all trooped upstairs. Dick was sitting at his desk. There was no hint of a welcoming smile. His charm had all but deserted him, and the years of schoolmaster training came to the fore. Having heard SIS's report, "White looked unconvinced. He smoothed his temples. He shuffled his papers. The clock ticked gently in the corner. Telltale signs of panic oozed from every side of the room. "We must do everything to help you, of course. I will go and see the PM this evening, and see if I can head this thing off." Cumming was tasked to help SIS mastermind the cover-up.

An MI5 officer and- a senior police officer sped to the Portsmouth hotel. They requested the registration book and tore e out the page with Crabb's name. The hotel's owner was given a receipt for the page and a warning not to mention the incident. By then, the Ordjonikidze's commander had alerted his superiors that the crew had spotted a frogman surfacing between their ship and an escorting destroyer. No former protest was initially lodged but during a reception the incident was mentioned by the commander to his British hosts. The commander-in-chief Portsmouth, denying knowledge of any frogman, assured the Russian there would be an Inquiry and hoped that all discussion had been terminated.

On 29 April, the Admiralty curtly announced that Crabb "is presumed to be dead as a result of trials with certain underwater equipment". This bland statement about a well-known character provoked newspaper suspicions and their inquiries were fuelled by a Soviet leak about the subsequent protest to the Admiralty.

Eden was not told of Crabb's disappearance until 3 May. Furious that a grubby shadow had been cast over his international diplomacy and ignoring similar operations by the Soviets against the Royal Navy, Eden told the Commons the next day that Crabb was "presumed" dead and added an unprecedented rider: "I think It is necessary, in the special circumstances of this case, to make It clear that what was done was done without the authority or the

knowledge of Her Majesty's ministers. Appropriate disciplinary steps are being taken." Ten days later, in the wake of the subsequent furore, which had exposed the background to the whole operation, Eden insisted in another Commons debate that his explicit instructions had been disobeyed.On his return to Downing Street, Eden railed to Sir Norman Brook, the cabinet secretary. SIS, he shouted, was incompetent and inadequate. Its future could not be trusted under the present management. He ordered that Sinclair's retirement should be rapidly advanced. Who, asked the prime minister, was his successor? The internal candidate was Jack Easton, second in command of RAF intelligence during the war, organising special operations with SOE and SIS, and a member of SIS since 1945.

By informal agreement, an RAF officer was next on the rote to become chief. But Brook disparaged Easton. Although reliable, he was judged neither experienced nor inspired enough to reform SIS. The outstanding candidate, Brook advised, was White. Eden reacted with resignation rather than rapture.

In any country, to transfer the head of domestic counter intelligence to direct the nation's foreign intelligence service

is rare. Not only are the two tasks markedly different, but mutual antagonism between the services is common. In those circumstances, White's summons to Downing Street owed everything to Brook, a grammar-school-educated, unrelenting and accomplished bureaucrat who held White in great esteem.In their initial conversation, Brook confided that Eden was neither fit nor the rational strategist he had known during the war. There were, he said, great difficulties ahead. "We need you, Dick," explained Brook, "because you know what the British public will tolerate. You need to bring those qualities to SIS." White admitted his reluctance to accept the post. His arguments were heartfelt. He had barely started his reorganisation of MI5; he was devoted to the service; and he knew nothing of foreign intelligence. Unable to sway Brook, he consulted Newsome. The permanent secretary's advice was conclusive: "You cannot refuse a job you're offered."

White's candidature, signalling a shift of power from the defence establishment, was strongly opposed by Sinclair. After their heated arguments about Philby, the retiring chief bore considerable animosity towards White and insisted that Easton should succeed. Among White's supporters were Patrick Reilly, who had proposed him as chief six years earlier, Patrick Dean and Harold Macmillan, with whom White had become "very close". Sinclair's protests were heard and ignored. The appointment naturally remained unknown beyond a small circle of Whitehall officials. Even if newspaper editors came to hear of the change, they were effectively forbidden to publish news about the upheaval.

Within MI5, news of White's imminent departure spread gloom. His reforms had only just begun and the contemporaneous award of a knighthood to Blunt, a suspect among ! some senior MI5 officers, confirmed how much was left undone. According to Wright, White's transfer "bolstered" the status of SIS but "condemned the Service he left to ten years of neglect," because his successor was Roger Hollis. "The era of elegance and modernisation had ended," wrote Wright, and events would prove him partially correct. White justified his deputy's promotion on the ground that he was the best man available, a poor reflection on MI5 and on White himself.

(5) Gordon Corera, The Art of Betrayal (2011)

The mid-1950s came to be known as "the horrors" by the MI6 officers who lived through those years. The wildmen known within the service as the Robber Barons championed aggressive covert operations but were coming unstuck in a spectacular and occasionally grisly way. The emerging myth of James Bond met its counterpoint in the sad tale of Lionel "Buster" Crabb. In April 1956, the Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev made a high-profile trip to Britain on board the state-of-the-art cruiser the Ordzhonikidze. This was an important visit for Anthony Eden who wanted to play the statesman in the new, friendlier, post-Stalin era. The MI6 London station - run by Nicholas Elliott with Andrew King as his deputy - decided that the visit was too good an opportunity to miss and ten days beforehand put up a list of six operations to MI6's Foreign Office adviser. The Admiralty had been particularly keen to understand the underwater-noise characteristics of the Soviet vessels. The placing of a Foreign Office adviser inside MI6 was part of a drive to put the service on a somewhat tighter leash, but when an MI6 officer ambled into his office for a ten-minute chat about the plans, the adviser came away thinking they would then be cleared at a higher level (as some sensitive operations were) while Elliott and his colleagues assumed that the quick conversation constituted clearance. The problem was that the Prime Minister had explicitly ordered that no risky operations were to be carried out and had already vetoed a number of plans (including bugging Claridge's Hotel where the Soviets were staying and another operation involving a catamaran).

The operation bore all the hallmarks of the over-confident amateurishness of the period. Crabb was an ageing frogman who had an impressive, but increasingly distant, war record foiling attacks on Allied shipping with daring dives. He was now, like others, well past his prime and living on the legends of the past. His private life was a mess with a failed marriage, gambling, drink and depression. Diving and secret work were his escape and he begged to be allowed to undertake one more mission. Crabb and a young M16 officer checked into a local hotel under their real names and Crabb slugged back five double whiskies the night before the dive. Where Bond battled the bad guys in the crystal-clear Caribbean, the diminutive Crabb plunged into the cold, muddy tide of Portsmouth Harbour just before seven in the morning. He had about ninety minutes of air and by 9.15 it was clear something had gone wrong. For a while, it looked like the whole affair might be hushed up. The MI6 officer went back to the hotel to rip out the registration page. The hotel owner went to the press, who sniffed a good story. The disappearance of a well-known hero could not be covered up.

The Prime Minister, who for weeks was not even told of Crabb's disappearance, was furious when the story broke, taking MI6's recklessness and amateurishness as a personal affront. He was so angry that he broke with the normal "neither confirm nor deny" rule over intelligence operations and told the Commons, "I think it is necessary, in the special circumstances of this case, to make it clear that what was done was done without the authority or knowledge of Her Majesty's Ministers. Appropriate disciplinary steps are being taken." Elliott, to cover his own failings, blamed the politicians. "A storm in a teacup was blown up by ineptitude into a major diplomatic incident ... he (Eden) flew into a tantrum because he had not been consulted and a series of misleading statements were put out which simply had the effect of stimulating public speculation." Others thought Elliott was responsible for a veritable "one man Bay of Pigs". A few wondered whether there had been a leak about the operation and if so from where. Just over a year later, a fisherman saw a black object floating thirty yards away in the water which looked like a tractor tyre. When he pulled it out with a hook he realised it was a headless, decaying corpse in a black frogman's suit. Crabb's ex-wife could not even identify what was left, fuelling wild speculation that Crabb had detected or had been abducted and taken to the Soviet Union. Decades later, a Soviet frogman would claim that a tip-off from a British spy meant that he had been lying in wait. Fearing that Crabb was planting a mine to blow up the ship, the frogman says he swam up from below to slash Crabb's air tubes and then his throat with a knife. The body was so small he at first thought it belonged to a boy. But he then found himself staring into the dying eyes of a middle-aged man. According to his unconfirmed account, he pushed the body away into the undercurrents, leaving a trail of blood. The reflection in the mirror held up before MI6 by the Crabb incident was not lean Bond but a drink-addled frogman doing something stupid on a semi-freelance basis. It was not pretty.

(6) Ben Macintyre, A Spy Among Friends (2014)

More than a year after Crabb's disappearance, a fisherman spotted a decomposing body floating in the water off Pilsey Island in Chichester Harbour. The head and hands had rotted away completely, but a post mortem concluded, from distinguishing marks on the remains preserved inside the Pirelli diving suit, that the small corpse was that of Lionel Crabb. The coroner's open verdict on the cause of death, and the absence of head and hands, left the way clear for a flood of conspiracy theory that has continued, virtually unabated, ever since: Crabb defected to the USSR; he was shot by a Soviet sniper; he had been captured and brainwashed and was working as a diving instructor for the Soviet navy; he had been deliberately planted on the Soviets as an MI6 double agent. A South African clairvoyant insisted Crabb had been sucked into a secret underwater compartment on the Ordzhonikidze, chained up and then dumped at sea. And so on. Eight years later, Marcus Lipton, the indefatigable MP, was still calling for the case to be reopened, without success.The Crabb mystery has never been fully explained, but the diminutive frogman did achieve a sort of immortality. Crabb has been cited as one of the models for James Bond. As an officer in Naval Intelligence, Ian Fleming had known him well, and the Crabb affair inspired the plot of Thunderball, in which Bond sets out to investigate the hull of the Disco Volante.

(7) Statement made by Pat Rose that was included in Don Hale's book, The Final Dive (2007)

I was first engaged to Lionel in 1948. We became engaged on the same day he received his George Medal. After that, we split up and we each married. It didn't work out and we were both divorced about the same time. We met once more and at the time he disappeared, we had been engaged for about four months.

On 16 April Lionel came around to my flat and we went out to a pub. We had lunch together but he was terribly jittery. He normally drank quite heavily, but he only had half a pint of beer and just picked at his food. I asked him what was wrong and he said he was going to Portsmouth the next day to test some equipment. Although I didn't want to go he persuaded me. On the journey down I threatened to break oft' our engagement if he didn't tell me what was really going on. I said he was always testing new gear, so there was nothing new in that. Finally. he admitted he was going to look at the bottom of the Russian cruiser. I said he had already done a mission like that before, but this time he said the Admiralty were sending him. I had met Matthew Smith a few weeks before. He talked like an American, and I didn't like him one bit. At Portsmouth. Crabbie said we could not stay in the same hotel because he had to leave and meet Smith. He said that if he didn't phone tomorrow, he would call in the evening. That was the last I saw of him.

(8) Don Hale, The Final Dive (2007)

Remarkably, at the time of Crabb's disappearance the First Sea Lord, Lord Louis Mountbatten, the Director of Naval Intelligence, Rear Admiral John Inglis and even the M16 chief Sir John Sinclair were all said to be out of the country. In later notes about the incident, Lord Mountbatten stated: "I returned from a long tour of South East Asia to find myself at the centre of a squall over the activities of' Cdr Crabb."

Mountbatten claimed he knew nothing about this mission until he was told by the Admiralty on his return. By that time, he said the press had got hold of the story, and it was clear that it scandal was about to break. He insisted he should have been told at once. The accuracy of some of his claims, however, has often been disputed and was certainly at variance with his own Vice-Chief of Naval Staff, Admiral Sir William Davis.

In his autobiography, Mountbatten asserted that he had instructed Davis before he left on his tour, that "no such operation was to be undertaken. He was justifying "what seemed superfluous precautions on the grounds that it seems irresistible for spies to look at ships' bottoms". Admiral Davis, though, claimed to have no knowledge of this instruction. And he said that Mountbatten agreed not to tell the First Lord of the Admiralty when it seemed likely that the story would never become public. He demurred only when Davis asked him to wait a few minutes until Cabinet Minister John Lang joined them.

Mountbatten's position regarding the Crabb incident came under scrutiny following attacks in the House of Commons, when the Labour MP. Lord Wigg, called out: "The man responsible is the First Sea Lord: he should be thrown out!" Wigg, who also knew that Lord Mountbatten was abroad at the time of the incident added: "Nothing in the Navy happens unless you want it to... they wouldn't have dared do it if they thought you would disapprove." And both the Daily Mirror and Daily Express vigorously attacked Mountbatten, with the First Sea Lord retorting by asking the Daily Mirror's Hugh Cudlipp: "Hugh, are you trying to get me sacked?"

Certain aspects of this embarrassing incident were later debated in Parliament. It caused mayhem within the establishment, and led to a massive breakdown in Anglo-Soviet relations.

(9) The Independent, review of Man Overboard (1st July, 2007)

There's a certain sort of Englishman who is deeply patriotic and hasn't a clue why: the Queen is infallible and politics begins and ends with "voting Conservative every four years". They're a dying breed in 2005, but post-War Britain was crawling with them. They had given all during the hostilities, but their civilian life offered neither the excitement nor the moral certainty.

But it's not even that simple. This isn't the mindless patriotism practiced by some. For this kind of Englishman, it was "string and sealing wax and a regular tot of bloody-mindedness" which singled out the British war effort. Binding identifies exactly "what separates us from the Cowhands [Americans]. They do not understand the necessity of indifference."

And they don't come much more indifferent than Commander Crabb – the real-life hero of Binding's delightful, surprising, read-in-a-single-glorious-gulp new novel. A heavy-drinking, unemployable, near-feckless wastrel before the war, Lionel Crabb was transformed by service into a heavy-drinking, unemployable, near-feckless Able Seaman. Eventually commissioned into bomb disposal, he was posted to underwater disposal in Gibraltar with the words "Frankly, Crabb, we wouldn't mind you drowning."

But there in the Mediterranean, "opposed to any form of exercise", he found his unexpected metier – deep sea diving. Protecting British shipping from the Italians' constantly inventive limpet mines and two-man subs, he made a considerable name for himself. He ended the war a Commander and won the George Medal. But that's when his problems started.

He was now surplus to requirements – and clearly still a determinedly loose cannon. But rarely do narrators come this unreliable – and this is the joy of Binding's writing: he captures the soul of a man who knows he is constantly making a hash of things but can barely admit it to himself.

He undoubtedly had a serviceable skill and once the enemy shifted from Berlin to Moscow, it was in even greater demand. Through his ever unreliable eyes, we see him being manipulated by agents, double agents and moles. That is until he finds himself on the other side of the Iron Curtain. Because Binding's novel aims to unravel the mystery of Crabb's disappearance: Crabb finally went down and didn't come up in 1956. Binding paints a picture of Crabb, now dying, looking back on two careers, one for the Royal Navy, the other for the Soviet Navy.

And if, like me, you wonder how on earth a wool-dyed patriot like Crabb could calmly work for the Reds, Binding has a last twist in the tale which makes the entire story slot into place.

(10) Mail on Sunday (27th October, 2006)

The fate of a Naval hero said to have been the model for fictional superspy James Bond was hushed up by the Government, secret documents reveal.

Commander Lionel 'Buster' Crabb, thought by some to have inspired Ian Fleming's iconic novels, went missing during a dive off Portsmouth in 1956.

The Government was keen to play down embarrassing claims that he had been spying on Russian ships docked in the harbour during the visit of Soviet leaders Nikita Khrushchev and Marshal Nikolai Bulganin.

Prime Minister Sir Anthony Eden told the House of Commons that it would "not be in the public interest" to disclose the circumstances of his death.

He added that "what was done was done without the authority or knowledge of Her Majesty's ministers".

The cover-up prompted wild speculation for years, including claims that he was alive and well and living in Russia as an officer in the Red Navy, and others that he was killed by the Soviets.

Secret documents relating to the controversy were released to the public today at the National Archives in Kew, south west London.

They reveal the determination of officials to cover up what really happened, even rejecting a request for maintenance from ex-wife Margaret Crabb.

Five months after Crabb's death, WH Lewin, head of Naval Law, wrote in a memo: "If this came out ... it would not seem to square very well with our statement that Crabb had been out of the Navy for over a year at the time of his death."

The official Admiralty line following the incident on 19 April was that Crabb had been "specially employed in connection with trials of certain underwater apparatus" and was missing presumed drowned.

But a memo from Rear Admiral JGT Inglis, director of naval intelligence, on June 21, explained that it was "considered essential" to avoid implicating top officers in Portsmouth.

In a 'bona fide' operation there would have been 'immediate and extensive rescue operations', he explained, while an unnamed diving officer who was with Crabb would have also taken action.

Instead, as Inglis points out: "The moment it became clear that a mishap had occurred (name blanked out) was ordered to return to his ship and take no further part in the affair."

If it had been a 'bona fide' operation, this would have exposed the other officer and the CinC to charges of "negligence, lack of humanity and error of judgment", which was considered unacceptable.

The secret account of an anonymous Lieutenant Commander, who assisted Crabb on the day of his disappearance, was seen publicly for the first time today.

He said that he had been asked, as an expert diver, to assist him "entirely unofficially and in a strictly private capacity" and there is little detail in the story.

The officer said: "He carried sufficient oxygen for an absence of a maximum of two hours submerged.

"His actions until disappearance under the surface were normal, and the conditions for diving were good. He was not seen by me again."

Navy officials were keen for this officer not to appear in public at a subsequent inquest after the headless body of a frogman was found in Chichester in June 1957.

It was decided to dispatch George William Bostock, a temporary clerical officer, to represent the Admiralty instead.

One of the secret documents explained: "He knows nothing of the background to the story and will not be able to answer any embarrassing questions even if they are asked."

The same document said: "The coroner is aware of the background to the case and is not asking for the appearance of any embarrassing naval witnesses."

The coroner ruled that it was Crabb's body that had been found. Even by 1972, the Navy wanted to keep the story quiet, and officials discussed the possibility of suspending the pension of a diver due to speak out in a planned BBC documentary on the case.

Howard Davies, archivist at the National Archives, said the extent of the cover-up suggested there was more about the case to be told.

"The conclusion that most people will draw is that there is a real intelligence angle to this which the authorities aren't ready to release," he said.

(11) Ben Macintyre, The Times (17th November, 2007)

One of the most bizarre and enduring espionage mysteries of the Cold War deepened yesterday when a retired Russian sailor came forward to claim that he had killed Buster Crabb, the naval war hero who died while spying on a Soviet ship docked in Portsmouth harbour in 1956.

The headless body of Commander Lionel “Buster” Crabb was washed up on the Sussex shore 14 months after a secret mission – to inspect the hull of the Soviet cruiser that had brought Nikita Khrushchev, the Russian President, on a state visit to Britain – went horribly wrong.

For more than half a century, MI6 has refused to explain what Crabb was doing, how he died and why a middle-aged, unhealthy veteran was chosen for a highly dangerous and diplomatically disastrous mission.

Eduard Koltsov has now given an interview to a Russian documentary team in which he claims that he was ordered to dive beneath the ship and investigate after a frogman was spotted in the water. Mr Koltsov claims that he cut Crabb’s throat after finding him attaching a limpet mine to the hull, according to a BBC report.

Mr Koltsov, who was then 23, was said to have shown the documentary-makers the dagger that he used to kill 47-year-old Crabb. “I saw a silhouette of a diver who was fiddling with something at the starboard, next to the ship’s ammunition stores. I swam closer and saw that he was fixing a mine,” he said.

Members of Crabb’s family expressed doubts that the former naval commander would have been sent to blow up the Soviet cruiser Ordzhonikidze, an act that would almost certainly have ignited war with the Soviet Union. “I simply don’t believe it,” said Lomond Handley, a relative of Crabb who has spent many years trying to unravel the affair.

The precise nature of Crabb’s mission has never been explained. What is certain, from documents released last year, is that British officials went to extraordinary lengths to try to cover it up. The former Royal Navy frogman was apparently recruited by MI6 to examine the cruiser for mine-laying hatches and sonar equipment, in direct defiance of orders from Downing Street.

During the Second World War, Crabb specialised in removing German limpet mines from Allied shipping, and was awarded the George Medal for bravery in 1944. He was nicknamed “Buster” after Buster Crabbe, the American Olympic swimmer and actor.

An eccentric figure on land, Crabb sported a monocle and carried a swordstick with a handle carved in the shape of a crab. But by 1956, he was past his prime. Far from being a James Bond character, he was by then middle-aged, drinking and smoking heavily, and in poor health.

The Crabb affair, one of the oddest and most unwise missions in espionage history, was a diplomatic disaster, prompting Soviet anger, the early retirement of the MI6 director John Sinclair, and a flood of speculation that continues today.

The official line from the Admiralty was that Crabb had died while “specially employed in connection with trials of certain underwater apparatus”. Sir Anthony Eden, then the Prime Minister, was questioned in the Commons and merely compounded the mystery by saying that any disclosure of the circumstances surrounding Crabb’s death would “not be in the public interest”.

He added that Crabb had acted “without the authority or the knowledge of Her Majesty’s ministers”, an indication that MI6 had ignored Eden’s instructions not to spy on the visiting Russians. At the time, it was reported that a Soviet seaman had spotted a frogman close to the ship, but government press officers were instructed to mount a cover-up.

The coroner could not determine a cause of death, prompting a wave of conspiracy theories: some claimed the frogman had been decapitated by the propellers of the Ordzhonikidze, others that he had been brainwashed or murdered by the Russians. Some suggested he had defected, having been recruited as a communist spy by Anthony Blunt.

Nicholas Elliott, a former MI6 officer who had been involved in the mission, claimed in his memoirs that Crabb “almost certainly died of respiratory trouble, being a heavy smoker and not in the best of health, or because some fault developed in his equipment”.

This year the Ministry of Defence disclosed that, in 1955, navy divers had successfully carried out an unauthorised espionage operation to inspect sonar equipment on a Soviet cruiser in Portsmouth.

Crabb has often been cited as one of the models for James Bond. Ian Fleming knew Elliott and was fascinated by the Crabb affair, but there is no evidence that Crabb was the original Bond: James Bond, for a start, is always successful, whereas Crabb, self-evidently, was not.

Fleming did use the incident as inspiration for Thunderball, in which Bond sets out to investigate the hull of the Disco Volante. Unlike Crabb, however, Bond returns intact.

References

(1) Richard Compton-Hall, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004-2014)

(2) Ben Macintyre, A Spy Among Friends (2014) page 193

(3) Time Magazine (14th May, 1956)

(4) Nicholas Elliott, With My Little Eye: Observations Along the Way (1994) page 24

(5) Ben Macintyre, A Spy Among Friends (2014) page 194

(6) Chapman Pincher, Their Trade is Treachery (1981) page 65

(7) Gordon Corera, The Art of Betrayal (2011) page 76

(8) Don Hale, The Final Dive (2007) page 172

(9) Tom Bower, The Perfect English Spy (1995) page 160

(10) Peter Wright, Spycatcher (1987) page 73

(11) Tom Bower, The Perfect English Spy (1995) page 160

(12) Ben Macintyre, A Spy Among Friends (2014) page 195

(13) Nicholas Elliott, With My Little Eye: Observations Along the Way (1994) page 25

(14) Peter Wright, Spycatcher (1987) page 73

(15) Gordon Corera, The Art of Betrayal (2011) page 76

(16) Chapman Pincher, Their Trade is Treachery (1981) page 65

(17) Time Magazine (14th May, 1956)

(18) Nicholas Elliott, With My Little Eye: Observations Along the Way (1994) page 25

(19) Anthony Eden, House of Commons (4th May, 1956)

(20) Anthony Eden, Full Circle (1960) page 365

(21) Gordon Corera, The Art of Betrayal (2011) page 78

(22) Ben Macintyre, The Times (17th November, 2007)

(23) Gordon Corera, The Art of Betrayal (2011) page 78