German League of Girls (Bund Deutscher Mädel)

In 1930 the Bund Deutscher Mädel (German League of Girls) was formed as the female branch of the Hitler Youth movement. It was set up under the direction of Hitler Youth leader, Baldur von Schirach. There were two general age groups: the Jungmädel, from ten to fourteen years of age, and older girls from fifteen to twenty-one years of age. All girls in the BDM were constantly reminded that the great task of their schooling was to prepare them to be "carriers of the... Nazi world view". (1)

The historian Cate Haste has pointed out: "The leadership immediately set about organizing youth into a coherent body of loyal supporters. Under Baldur von Schirach, himself only twenty-five at the time, the organization was to net all young people from ages ten to eighteen to be schooled in Nazi ideology and trained to be the future valuable members of the Reich. From the start, the Nazis pitched their appeal as the party of youth, building a New Germany.... Hitler intended to inspire youth with a mission, appealing to their idealism and hope." (2) Schirach promoted the idea of the German Girls' League as "youth leading youth". In fact, its leaders were part of "an enormous bureaucratised enterprise, rather than representative of an autonomous youth culture." (3)

The duties demanded of the German League of Girls (BDM) were regular attendance at club premises and camps run by the Nazi Party. Christa Wolf joined the BDM in Landsberg. Her unit used to meet every Wednesday and Saturday. She remembers the importance of singing songs at meetings. This included the following: "Onward, onward, fanfares are joyfully blaring. Onward, onward, youth must be fearless and daring. Germany, your light shines true, even if we die for you." (4)

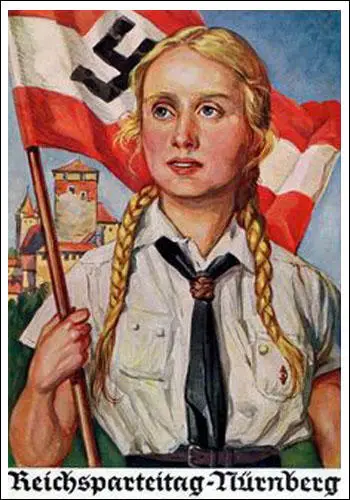

According to Richard Grunberger the ideal "German League of Girls type exemplified early nineteenth-century notions of what constituted the essence of maidenhood. Girls who infringed the code by perming their hair instead of wearing plaits or the 'Grechen' wreath of braids had it ceremoniously shaved off as punishment. As a negative counter-image Nazi propaganda projected the combative, man-hating suffragettes of other countries." (5)

Adolf Hitler and the German Girls' League

The German League of Girls was not a popular organization until the election of Adolf Hitler as Chancellor and in 1932 only had 9,000 members. (6) Traudl Junge was one of those who joined after the election: "In school and generally it was celebrated as a liberation, that Germany could have hope again. I felt great joy then. It was portrayed at school as a turning point in the fate of the Fatherland. There was a chance that German self-confidence could grow again. The words 'Fatherland' and 'German people' were big, meaningful words which you used carefully - something big and grand. Before, the national spirit was depressed, and it was renewed, rejuvenated, and people responded very positively." (7)

Melita Maschmann joined the German League of Girls on 1st March 1933 in secret because she knew her parents would disapprove. Like the other girls she was ordered to read Mein Kampf but she never finished the book. She argued that the BDM gave her a sense of purpose and belonging. Maschmann admitted that "she devoted herself to it night and day, to the neglect of her schooling and the distress of her parents". (8)

Elsbeth Emmerich was recruited by her school: "In High School, I became a member of the Jungmädel (Young Girls). We were all given the entry forms in class to fill in there and then, and told to take it home for our parents' signature.... I enjoyed being in the Jungmädel. We had to attend classes after school and learn about Adolf Hitler and his achievements. We did community work, singing to soldiers in hospitals and making little presents for them like bookmarks, or poems written out neatly. We also went on hikes and collected leaves and herbs for the war effort." (9)

Hedwig Ertl enjoyed the activities organized by BDM. "There were no class differences. You went on trips together without paying for it, and you were given exactly the same amount of pocket money as those who had lots of money and now you could go riding and skating and so on, when before you couldn't afford it. You could go to the cinema for 30 pfennings. We could never go to the cinema before, and suddenly things that had been impossible were there for us. That was incredible, those beautiful Nazi movies." (10)

Marianne Gärtner joined the local branch in Potsdam. This involved taking the oath: "I promise always to do my duty in the Hitler Youth, in love and loyalty to the Führer." Other mottos she was taught included: "Führer, let's have your orders, we are following you!", "Remember that you are a German!" and "One Reich, one people, one Führer!". As she later admitted: "I was, however, not thinking of the Führer, nor of serving the German people, when I raised my right hand, but of the attractive prospect of participating in games, sports, hiking, singing, camping and other exciting activities away from school and the home.... I acquired membership, and forthwith attended meetings, joined ball games and competitions, and took part in weekend hikes; and I thought that whether we were sitting in a circle around a camp fire or just rambling through the countryside and singing old German folk songs." (11)

Hildegard Koch was encouraged to join the BDM at the age of 15. A friend of the family, Gustav Motze, was a member of the Sturmabteilung (SA). He told Hildegard's father: "Your Hilde is a real Hitler girl, blonde and strong - just the type we need... Don't let her come under the degenerate influence of the Jews, make her join the BDM." Her father was sympathetic to the ideas of the Nazi Party but her mother, disliked the movement: "She was terribly old-fashioned and full of Christianity and all that sort of thing." Despite her mother's protests, Hildegard joined the BDM in 1933. (12)

The duties demanded of the BDM included regular attendance at club premises and camps run by the Nazi Party. Christa Wolf attended one in Landsberg: "In the Jungmädel camp, the leader or her deputies inspect the dormitory, the chests of drawers, the washrooms, every morning. One time the hairbrush of a squad leader was publicly displayed because it was full of long hairs. That was no way for a hair-brush to look if it belonged to a Jungmädel leader, the camp leader said in the evening roll call." From that moment on Christa "hid her hair-brush in the soap compartment of her trunk, because she couldn't manage to pick every last hair from her brush... because she didn't want the camp leader, of all people, to dislike her." (13)

Elsbeth Emmerich did not enjoy going away with the BDM: "We even went away to camp. I thought this might be exciting, but it wasn't like I imagined, even though it was right in the country in some lovely woodland. I was shouted at within minutes of arriving, for not picking up a bit of eggshell I'd dropped. We had to get up early each morning, standing to attention in the freezing cold and singing whilst the flag was being hoisted. Then someone stole my purse. My holiday was mainly doing what other people told you to all the time, like standing to attention and raising our arms for the Sieg Heil." (14)

Renate Finckh was only 10 years-old when she joined the BDM. Both her parents were active members of the Nazi Party. "At home no one really had time for me... at the BDM I finally found an emotional home, a safe refuge, and shortly thereafter also a space in which I was valued... I was filled with pride and joy that someone needed me for a higher purpose." Renate was also devoted to her leader, a teenager only three years older than herself. "We Hitler girls belonged together, we formed an elite within the German Volk community." (15)

Great pressure was put on young girls to join the BDM and by 1936 it had a membership of over 2 million. (16) In some industrial areas girls had some success in not joining the BDM. Effie Engel lived in Dresden: "We were constantly getting enlistment orders in school for the BDM. You were supposed to report and join up... In our area we had a lot of workers, left-wing oriented workers, there were many students in my class who said that they preferred sports and that they would never join up. In the end, almost half the class refused to join. So my class succeeded in this. But that hardly was possible for the classes after us, as they were put under a lot of pressure to join." (17)

Activities of the German League of Girls

In 1934, Trude Mohr, a former postal worker, was appointed as the leader of the BDM. In a speech soon after taking control of the organisation she argued: "We need a generation of girls which is healthy in body and mind, sure and decisive, proudly and confidently going forward, one which assumes its place in everyday life with poise and discernment, one free of sentimental and rapturous emotions, and which, for precisely this reason, in sharply defined femininity, would be the comrade of a man, because she does not regard him as some sort of idol but rather as a companion! Such girls will then, by necessity, carry the values of National Socialism into the next generation as the mental bulwark of our people." (18)

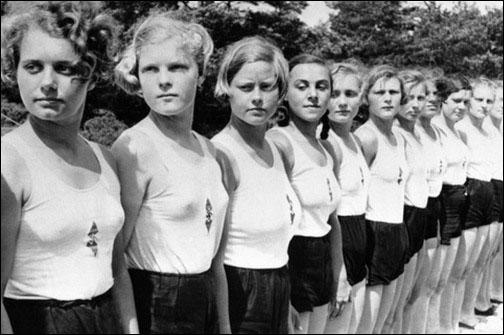

All girls in the BDM were told to dedicate themselves to comradeship, service and physical fitness for motherhood. In parades they wore navy blue skirts, white blouses, brown jackets and twin pigtails. (19) Parents complained about the time their children were forced to spend outside the home in activities organized by the BDM and the Hitler Youth. Its leader, Baldur von Schirach, argued "that the Hitler Youth has called up its children to the community of National Socialist youth so that they can give the poorest sons and daughters of our people something like a family for the first time." (20)

These arguments upset many parents. They felt that the Nazi Party was taking over control their children. Hildegard Koch constantly came into conflict with her mother over her membership of the BDM: "After all, we were the new youth; the old people just had to learn to think in the new way and it was our job to make them see the ideals of the new nationalised Germany". (21)

Members of the BDM later recalled that they welcomed the extra power they had over their parents: "As a young person, you were taken seriously. You did things which were important... Your dependence on your parents was reduced, because all the time it was your work for the Hitler Youth that came first, and your parents came second... All the time you were kept busy and interested, and you really believed you had to change the world." (22)

Susanne von der Borch was another girl whose mother did not want her to join the BDM. "My mother went early on, before Hitler was elected, to a political rally and she listened to him yelling. She was convinced that something terrible was happening to us. As a child, I could not judge. I was simply besotted by it." After she joined the BDM her parents called her our "Little Nazi". (23)

Ingeborg Drewitz joined the BDM in 1936 without daring to tell her parents. "Why? Well, because of the things that one thinks at age thirteen: I wanted to rebel against my parents at all cost because they disliked everything that everyone else liked." Gerda Zorn also secretly joined the BDM, even though her parents were members of the German Communist Party. She later recalled that she enjoyed the friendship, outings, and excitement "at working for a great cause". (24)

Other girls like Helga Schmidt wanted to join the BDM but her parents would not let her: "We were at first wild with enthusiasm about the Nazi regime. There was, of course, the Hitler Youth, which my father was against. Therefore, even though the school exerted a bit of pressure on us to join, I was among those who were not in the League of German Girls (BDM). And it was not pleasant for the older child to have to stand on the sidelines, because that is not one's inclination." (25)

Karma Rauhut, who attended a private school in Berlin, developed a hostility to the Nazi Party and refused to join the BDM. "One really had to be in the BDM. The trick was that I went to school (a private girls' school her mother had attended) in the city of Berlin, but lived so to speak in another district, so they never figured it out, because they had no communication with each other. In my village I always said more or less, I'm in it in Berlin. And at school I always said, I'm in the BDM at home. One could always create certain freedoms, right? But naturally the thing was, I did not have a uniform. And when there were big marches or school festivals, the teacher always said, Put on a black skirt and a white blouse, so it's not so noticeable. This odd jacket and the scarf and this leather scarf holder and the shoes, I would have died rather than put it on." (26)

Susanne von der Borch claimed that her school work suffered because of her BDM activities: "I only managed to get to the end of the school year with the help of my classmates. I was a very bad pupil. I was only good at sport, biology and sketching, I was very bad at all the rest... And the school didn't dare do anything so I had my freedom and didn't go to school if I didn't want to." She was told in the BDM and at school that Germans deserved to control the world: "We are the master race... The world presented to us was filled only with beautiful people, master race people, full of sport and health. And, well, I was proud about that, and inspired by it. I would call this a grand seduction of youth." (27)

The girls in the BDM spent a lot of time marching through the streets. Inge Scholl, who later joined the White Rose resistance group, that the German people were mesmerized by the "mysterious power" of "closed ranks of marching youths with banners waving, eyes fixed straight ahead, keeping time to drumbeat and song". The sense of fellowship was "overpowering" for they "sensed that there was a role for them in a historic process". (28)

Hildegard Koch later pointed out that she always appeared in the front line. "The Gau Leader herself had picked me from amongst hundreds of girls. I was half a head taller than the tallest of them and had wonderful long blonde hair and bright blue eyes. I had to step out in front of the others and the Gau Leader pointed to me and said: 'That is what a Germanic girl should look like; we need young people like that.' Once I was photographed and my picture appeared on the tide page of the BDM journal Das deutsche Mädel." Koch was also successful at fund-raising. "When we had any street collections my box was always full first and I worked on the other girls to buck up so that our group always made a good impression wherever we went." (29)

Karma Rauhut was one of those who refused to join the BDM. The headmaster of her school called her to his office and said: "Well, my dear child, I cannot give you your diploma. And I must tell you, you will never amount to anything. You are not in the BDM, you don't join the Party... You might become a worker, but you'll never be anything." Karma replied: "Well, the world is round. It revolves." The headmaster was furious with this comment and reported her to the authorities. (30)

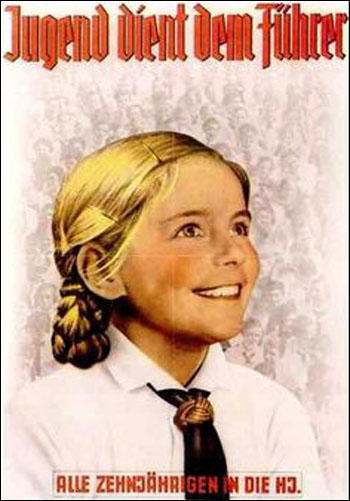

Ruth Mendel from Frankfurt remembers seeing a lot of posters in Nazi Germany advertising the BDM and the Hitler Youth: "They had these cute little girls with these blond pigtails and a couple of freckles on their noses and that was the ideal German girl. And they had these cute boys for the Hitler Youth. They were plastered all over." (31) This included on the walls of churches who objected to posters that depicted lightly clad BDM members. (32)

The girls in the BDM were required to pass certain physical tests. They had to run 60 metres in twelve seconds, to jump more than 2.5 metres, throw a ball over a distance of 20 metres, swim 100 metres and complete a two hours route march. Other physical requirements included somersaulting and tightrope walking. (33)

Susanne von der Borch was considered to be the "ideal German girl" as she was "tall, blonde-haired, blue-eyed and mad about sport". She pointed out: "This was my world. It fitted my personality because I had always been very sporty and I liked being with my friends... I always wanted to get out of the house. So this was the best excuse for me. I couldn't be at home, because there was always something happening... riding, or skating, or summer camp. I was never at home." (34)

Members of the BDM spent a lot of time fund-raising. This upset some people: "What I considered negative was the street collections, which were held for one reason or another nearly every week. Collections were held for this and that - and in a rather pushy way. And house wardens were assigned to go around from house to house with lists for collections... The notion was that, whoever doesn't donate is the enemy." (35) Hildegard Koch enjoyed this activity. "When we had any street collections my box was always full first and I worked on the other girls to buck up so that our group always made a good impression wherever we went." (36)

Young Women in Nazi Germany

Adolf Hitler had strong views on how young women should behave. He described his own ideal woman as "a cute, cuddly, naïve little thing - tender, sweet, and stupid." (37) This is why he was attracted to Eva Braun. According to Alan Bullock, the author of Hitler: A Study in Tyranny (1962): "Hitler became genuinely fond of Eva. Her empty-headedness did not disturb him; on the contrary, he detested women with views on their own." (38)

Hitler also disliked women who smoked and wore make-up. He made it clear about how young women in Nazi Germany should behave. The American journalist, Wallace R. Deuel, pointed out that he read in the Völkischer Beobachter, a newspaper controlled by the Nazi Party, that: "The most unnatural thing we can encounter in the streets is a German woman, who, disregarding all laws of beauty, has painted her face with Oriental warpaint." (39)

The German League of Girls played an important role in developing these values: "They were trained in Spartan severity, taught to do without cosmetics, to dress in the simplest manner, to display no individual vanity, to sleep on hard beds, and to forgo all culinary delicacies; the ideal image of those broad-hipped figures, unencumbered by corsets, was one of radiant blondeness, crowned by hair arranged in a bun or braided into a coronet of plaits. As a negative counter-image Nazi propaganda projected the combative, man-hating suffragettes of other countries." (40)

There was also a campaign against young women who smoked. Medical experts wrote articles claiming there was a positive correlation between excessive nicotine indulgence and infertility. One report argued that smoking harmed the ovaries and that a marriage between heavy smokers only produced 0.66 children on average compared to the normal average of three. (41)

If caught smoking, members of the German League of Girls were in danger of being expelled. Hedwig Ertl, a loyal member of the BDM, fully supported these values: "The German woman must be faithful. She must not wear make-up and she should not smoke. She must be industrious and honest and she must want to have lots of children and be motherly." (42)

There was also a campaign in German newspapers against the idea of wearing trousers. Women were described as those "trouser-wenches with Indian warpaint". Magda Goebbels liked wearing trousers and she gained the support of her husband, Joseph Goebbels, to defend like-minded women: "Whether women wear slacks is no concern of the public. During the colder season women can safely wear trousers, even if the Party mutinies against this in one place or another. The bigotry bug should be wiped out." (43)

Unmarried Mothers

Adolf Hitler argued that the BDM should play its role in persuading women to have more children. "Good men with strong character, physically and psychically healthy, are the ones who should reproduce extra generously... Our women's organizations must perform the necessary job of enlightenment.... They must get a regular motherhood cult going and in it there must be no difference between women who are married... and women who have children by a man to whom they are bound in friendship.... On special petition men should be able to enter a binding marital relationship not only with one woman, but also with another, who would then get his name without complications." (44)

The Nazi government encouraged the mixing of the sexes. The Ulm district of the Hitler Youth pointed out the organization of mixed social evenings with dancing "had a more beneficial effect on the relationship between boys and girls than any number of exhortations and lectures". (45) In 1936, when approximately 100,000 members of the Hitler Youth and the BDM attended the Nuremberg Rally, 900 girls between fifteen and eighteen returned home pregnant. Apparently, the authorities failed to establish paternity in 400 of these cases. (46)

large families to visit the park while the mothers of the infants were at work.

The daughter of the American ambassador in Germany, Martha Dodd, argued: "Young girls from the age of ten onward were taken into organizations where they were taught only two things: to take care of their bodies so they could bear as many children as the state needed and to be loyal to National Socialism. Though the Nazis have been forced to recognize, through the lack of men, that not all women can get married." (47)

Hildegard Koch could not understand why her mother was so upset by these stories of young girls getting pregnant. "After all, we were the new youth; the old people just had to learn to think in the new way and it was our job to make them see the ideals of the new nationalised Germany. When I told her about the camp with the Hitler Youth she was shocked. Well, suppose a young German youth and a German girl did come together and the girl gave a child to the Fatherland - what was so very wrong in that? When I tried to explain that to her she wanted to stop me going on in the BDM - as if it was her business! Duty to the Fatherland was more important to me and, of course, I took no notice." (48)

Isle McKee wrote about her experiences in the German League of Girls in her autobiography, Tomorrow the World (1960): "We were told from a very early age to prepare for motherhood, as the mother in the eyes of our beloved leader and the National Socialist Government was the most important person in the nation. We were Germany's hope in the future, and it was our duty to breed and rear the new generation of sons and daughter. These lessons soon bore fruit in the shape of quite a few illegitimate small sons and daughters for the Reich, brought forth by teenage members of the League of German Maidens. The girls felt they had done their duty and seemed remarkably unconcerned about the scandal." (49)

Members of the BDM went to camp and hostels for long periods of time. They also worked on farms together. William L. Shirer, an American journalist, visited these camps. "The girls lived sometimes in the farmhouses and often in small camps in rural districts from which they were taken by truck early each morning to the farms. Moral problems soon arose. Actually, the more sincere Nazis did not consider them moral problems at all. On more than one occasion I listened to women leaders of the Bund Deutscher Mädel lecture their young charges on the moral and patriotic duty of bearing children for Hitler's Reich - within wedlock if possible, but without it if necessary." (50)

German League of Girls and Anti-Semitism

Melita Maschmann claimed that she disapproved of the anti-semitism of the Nazi Party but was willing to end contact with her Jewish school friend. She later argued that she did this out of duty "because one could only do one or two things: either have Jewish friends or be a National Socialist." (51)

Hedwig Ertl became convinced that the Germans were the master race. The BDM and the school she attended was an important factor in this: "We had a history teacher who was a very committed National Socialist, and we had four Jewish pupils. And they had to stand up during the class, they weren't allowed to sit down. And one after the other they disappeared, until none were left, but nobody thought much about it. We were told they had moved.... We were told all the time that first the Jews are a lower kind of human being, and then the Poles are inferior, and anyone who wasn't Nordic was worthless." (52)

Others like, Hildegard Koch, were clearly anti-semitic: "As time went on more and more girls joined the BDM, which gave us a great advantage at school. The mistresses were mostly pretty old and stuffy. They wanted us to do scripture and, of course, we refused. Our leaders had told us that no one could be forced to listen to a lot of immoral stories about Jews, and so we made a row and behaved so badly during scripture classes that the teacher was glad in the end to let us out. Of course, this meant another big row with Mother - she was pretty ill at that time and had to stay in bed and she was getting more and more pious and mad about the Bible and all that sort of thing. I had a terrible time with her.... But the real row with Mother came when the BDM girls refused to sit on the same bench as the Jewish girls at school."

salute and singing the Horst-Wessel, the unofficial anthem of the Nazi Party.

Hildegard Koch and her BDM friends began a campaign against the Jewish girls in her class. "The two Jewish girls in our form were racially typical. One was saucy and forward and always knew best about everything. She was ambitious and pushing and had a real Jewish cheek. The other was quiet, cowardly and smarmy and dishonest; she was the other type of Jew, the sly sort. We knew we were right to have nothing to do with either of them. In the end we got what we wanted. We began by chalking 'Jews out!' or 'Jews perish, Germany awake!' on the blackboard before class. Later we openly boycotted them. Of course, they blubbered in their cowardly Jewish way and tried to get sympathy for themselves, but we weren't having any. In the end three other girls and I went to the Headmaster and told him that our Leader would report the matter to the Party authorities unless he removed this stain from the school. The next day the two girls stayed away, which made me very proud of what we had done." (53)

Jutta Rüdiger, who was later to become the leader of the BDM, claims that the organization did not promote anti-semitism. She claimed that she told members: "Jews are not bad people... They are just very different to us in their thinking and their behaviour, and that's why they shouldn't control politics and culture... We said that they should marry a German, or a European who was a relative of our race, not a foreigner... Only the best German soldier is suitable for you, for it is your responsibility to keep the blood of the nation pure." (54)

Susanne von der Borch explained what she was told in the BDM and at school: "We are the master race... The world presented to us was filled only with beautiful people, master race people, full of sport and health. And, well, I was proud about that, and inspired by it. I would call this a grand seduction of youth." (55)

Some parents were appalled by their children's anti-semitism. Hedwig Ertl, remembers that at the age of ten being punished by her parents for expressing such views. As a child, she said to her father, "The Jews are our misfortune". She later recalled: "He looked at me in horror and slapped me in the face. It was the first and only time he hit me. And I didn't understand." Hedwig felt that her father did not understand the significance of "this great movement". (56)

Denunciations of parents by children was encouraged by the BDM and schoolteachers. It has been claimed that many parents "were alarmed by the gradual brutalisation of manners, impoverishment of vocabulary and rejection of traditional values". Michael Burleigh has argued in The Third Reich: A New History (2001): "Their children became strangers, contemptuous of monarchy or religion, and perpetually barking and shouting like pint-sized Prussian sergeant-majors. In sum, children appeared to have become more brutal, fitter and stupider than they were." (57)

Growth of the German Girls' League

In 1936 there was a massive drive by Baldur von Schirach to recruit all ten-year-old year olds into the BDM. Posters of fresh-faced, smiling young girls in uniform with swastikas in the background proclaimed "All Ten-Year-Olds To Us" or "All Ten-Year-Olds Belong to Us".

After Gertrud Scholtz-Klink married in 1937, she was required to resign her position (the BDM required members to be unmarried and without children in order to remain in leadership positions), and was succeeded by Dr. Jutta Rüdiger, a doctor of psychology from Düsseldorf. Rüdiger made a speech about her plans for the BDM on 24th November 1937: "The task of our League is to bring young women up to pass on the National Socialist faith and philosophy of life. Girls whose bodies, souls and minds are in harmony, whose physical health and well-balanced natures are incarnations of that beauty which shows that mankind is created by the Almighty... We want to train girls who are proud to think that one day they will choose to share their lives with fighting men. We want girls who believe unreservedly in Germany and the Führer, and will instill that faith into the hearts of their children. Then National Socialism and thus Germany itself will last for ever." (58)

Heinrich Himmler complained about the look of the BDM and considered their uniforms too masculine. Himmler told Rüdiger: "I regard it as a catastrophe. If we continue to masculinize women in this way, it is only a matter of time before the difference between the genders, the polarity, completely disappears." (59) A new uniform was designed and it was eventually approved by Adolf Hitler: "I have always told the Mercedes company that a good engine is not enough for a car, it needs a good body as well. But a good body is also not enough on its own." Rüdiger later recalled that she was "very proud that he had compared us to a Mercedes Benz car." (60)

According to Jutta Rüdiger, her commanding officer, Baldur von Schirach always used to say, "You girls should be prettier.... When I sometimes watch women getting off a bus - old puffed-up women - then I think you should be prettier women. Every girl should be pretty. She doesn't have to be a false, cosmetic and made-up beauty. But we want the beauty of graceful movement."

Joseph Goebbels also became concerned about what he called the "masculine vigour" of the BDM. He told one of his department chiefs, Wilfried von Oven: "I certainly don't object to girls taking part in gymnastics or sport within reasonable limits. But why should a future mother go route-marching with a pack on her back? She should be healthy and vigorous, graceful and easy on the eye. Sensible physical exercise can help her to become so, but she shouldn't have knots of muscle on her arms and legs and a step like a grenadier. Anyway, I won't let them turn our Berlin girls into he-men." (61)

Labour Service

At first, Adolf Hitler claimed that all the Nazi children groups were voluntary organizations. However, by 1938, laws were passed that meant that membership of the became obligatory. All other children groups such as the scouts were banned. By 1939 was estimated that virtually every young German aged between ten and eighteen was a member of the BDM or the Hitler Youth. (62)

In 1939 all young women up to the age of twenty-five had to compete a year of Labour Service before being allowed to take up paid employment. Nine out of ten young women were sent to farms where they lived in barrack-like accommodation under close supervision. It was seen as the female parallel to compulsory military service, aimed at producing a trained labour force in the event of war. It was also a source of cheap labour as the girls received only pocket money rather than wages. (63)

Melita Maschmann did her Labour Service in rural East Prussia. She later recalled that she found the whole experience uplifting: "Our camp community was a model in miniature of what I imagined the National Community... Never before or since have I known such a good community, even where the composition was more homogeneous in every respect. Amongst us there were peasant girls, students, factory girls, hairdressers, schoolgirls, office workers and so on... The knowledge that this model of a National Community had affected me such intense happiness gave birth to an optimism to which I clung obstinately until 1945." (64)

Hildegard Koch was sent to a camp in Silesia. "Our main job was helping on the land at the surrounding estates. This, of course was quite new to me. I had never done anything like it before, but I tried hard and being tall and strong I was soon quite good at it. We had a pretty uniform which suited me very well. I already knew the importance of cleanliness and neatness from the BDM and our Camp Leader took a liking to me from the beginning. After a couple of months she made me assistant to the Leader in charge of the kitchen and washhouse." (65)

When the Nazis took power women constituted about a fifth of the entire student body. Adolf Hitler was opposed to the idea of women being educated at university and over the next few years numbers dropped dramatically. However, in the build up to war young men were forced into military service. As a result, the number of young women going to university doubled and by 1943 had reached an all-time high of 25,000. (66)

German Girls' League in Poland

On 23rd August, 1939, Adolf Hitler and Joseph Stalin signed the Nazi-Soviet Pact. A week later, on 1st September, the two countries invaded Poland. Within 48 hours the Polish Air Force was destroyed, most of its 500 first-line planes having been blown up by German bombing on their home airfields before they could take off. Most of the ground crews were killed or wounded. In the first week of fighting the Polish Army had been destroyed. On 6th September the Polish government fled from Warsaw. (67)

After the government surrendered later that month, Poland was designated as an area for "colonization" by ethnic Germans. On 21st September, 1939, Reinhard Heydrich issued an order authorizing the ghettoization of Jews in Poland. They were expelled from their homes, their land was expropriated and they were deported to the eastern areas of Poland or to ghettos in the cities. (68)

An estimated 500,000 Germans, many living in territories in the Soviet sphere of influence, were now offered land in central Poland. It was decided to send members of the German Girls' League (BDM), under Schutzstaffel (SS) control, to "feminize and domesticate the conquest". Their task was to "Germanize" them, "teaching German culture and customs to the families, many of whom didn't even speak the language." (69)

Susanne von der Borch was asked to a resettlement camp of 800 Bessarabian Germans in central Poland, to teach children art and woodwork. "I told my mother about it and she said to me, literally: If you do that and if you go there, then I never want to speak to you again. And I don't want to see you ever again. And I thought, I have to risk that.... Imagine, I was seventeen years old. I was a blonde girl. My parents were writing me off. They knew the camps were run by the SS and they thought I was going to be drawn into their hands and that would be my fate... Formerly they had been rich farmers, breeding sheep, and they were plunged into misery. They didn't have any ration cards, they were living in poverty in these camps." (70)

In 1941 Susanne visited the Jewish ghetto in Lodz: "The windows were covered with paint so you couldn't see through. The tram doors were locked and then we drove through the ghetto. People had already scratched little peep holes in the paint. And I scratched a little more to see as much and as clearly as possible what was happening in the ghetto. Jewish children stood there, half-starved, wearing their Jewish stars, at the fence, this barbed wire fence. They were in a terrible state, dressed only in rags, like all the other people. What I saw - it was dreadful. It was worse than my worst fears... I saw one Jewish child, I couldn't see whether it was a boy or a girl, and he was there at the fence and he was looking out with huge eyes, starved eyes, in rags and obviously in despair... The ghetto was horrific and when I returned to the camp I was totally shattered." (71)

Hedwig Ertl was recruited to be a teacher at a German school in Poland: "The Poles were told that they had a short time to get out and they could take with them a few possessions... They didn't want to be resettled, they were really fed up, because they had very bad quality land and they couldn't get along with... I would say they were bitter, but I never experienced anyone who fought it, or threw stones or showed outrage. They went in silence... Looking back, I never had the feeling of doing something that wasn't right." (72)

On her return to Germany, Susanne von der Borch made a report on her experiences for the BDM. She decided to include "everything that was important to me, I didn't keep silent about anything. I didn't gloss over anything." Her group leaders were horrified; BDM reports were read out to the girls at the weekly home evenings. One of the leaders told her: "You know that concentration camps are there for young people too." The report was returned to her a few weeks later with her signature, "but all the things that were important to me had been taken out. It was a beautiful trip and an exciting trip, and it was just a description of a trip". However, Susanne was not punished for her report but she now decided to distance herself from the organization: "For me personally, I drew the line and decided that this movement, which had been so very important, was now finished for me." (73)

BDM and the War Effort

During the Second World War there was an acute labour shortage. Jutta Rüdiger was at a meeting where Heinrich Himmler called for German women to have more children: "He (Himmler) said that in the war a lot of men would be killed and therefore the nation needed more children, and it wouldn't be such a bad idea if a man, in addition to his wife, had a girlfriend who would also bear his children. And I must say, all my leaders were sitting there with their hair standing on end. And it went further than that. A soldier wrote to me from the front telling me why I should propagate an illegitimate child." A deeply shocked Rüdiger replied: "What! I don't do that." (74)

Some members of the BDM were asked to take part in the Schutzstaffel (SS) breeding programme. Hildegard Koch was told by her BDM leader: "What Germany needs more than anything is racially valuable stock". She was sent to an old castle near Tegernsee. "There were about 40 girls all about my own age. No one knew anyone else's name, no one knew where we came from. All you needed to be accepted there was a certificate of Aryan ancestry as far back at least as your great grandparents. This was not difficult for me. I had one that went back to the sixteenth century, nor had there ever been a smell of a Jew in our family."

Koch was then introduced to several SS men. "They were all very tall and strong with blue eyes and blond hair... We were given about a week to pick the man we liked and we were told to see to it that his hair and eyes corresponded exactly to ours. We were not told the names of any of the men. When we had made our choice we had to wait till the tenth day after the beginning of the last period, when we were again medically examined and given permission to receive the SS men in our rooms at night... He was a sweet boy, although he hurt me a little, and I think he was actually a little stupid, but he had smashing looks. He slept with me for three evenings in one week. The other nights he had to do his duty with another girl. I stayed in the house until I was pregnant, which didn't take long." (75)

Melita Maschmann was a member of the BDM who was totally opposed to this breeding programme. Lynda Maureen Willett argues that Maschmann played a key role in fighting against this "population policy". "Maschmann states that one of the male leaders in the Hitler Youth had presented an argument for bigamy, with racially suitable women, to ensure the numbers of babies produced... Maschmann reports that this debate also began to go on in public. Maschmann herself became involved in producing leaflets and reports against this policy." (76)

In 1942 Martin Bormann suggested that the BDM established women's battalions to defend Nazi Germany. The BDM leader, Jutta Rüdiger replied: "That is out of the question. Our girls can go right up to the front and help them there, and they can go everywhere, but to have a women's battalion with weapons in their hands fighting on their own, that I do not support. It's out of the question. If the Wehrmacht can't win this war, then battalions of women won't help either." Baldur von Schirach said "Well, that's your responsibility". Rüdiger retorted: "Women should give life and not take it. That's why we were born." (77)

However, when the war began to go badly for Germany, attitudes began to change. In September 1944 German women began to be conscripted to reinforce frontier fortifications. They were now ordered to fight alongside the Nazi Party controlled citizen militia. (78) When the Red Army was advancing towards in Berlin in 1945 Rüdiger instructed BDM leaders to learn to use pistols for self-defence. (79)

Primary Sources

(1) Martha Dodd, My Years in Germany (1939)

Young girls from the age of ten onward were taken into organizations where they were taught only two things: to take care of their bodies so they could bear as many children as the state needed and to be loyal to National Socialism. Though the Nazis have been forced to recognize, through the lack of men, that not all women can get married. Huge marriage loans are floated every year whereby the contracting parties can borrow substantial sums from the government to be repaid slowly or to be cancelled entirely upon the birth of enough children. Birth control information is frowned on and practically forbidden.

Despite the fact that Hitler and the other Nazis are always ranting about "Volk ohne Raum" (a people without space) they command their men and women to have more children. Women have been deprived for all rights except that of childbirth and hard labour. They are not permitted to participate in political life - in fact Hitler's plans eventually include the deprivation of the vote; they are refused opportunities of education and self-expression; careers and professions are closed to them.

(2) Trude Mohr, speech (June, 1934)

We need a generation of girls which is healthy in body and mind, sure and decisive, proudly and confidently going forward, one which assumes its place in everyday life with poise and discernment, one free of sentimental and rapturous emotions, and which, for precisely this reason, in sharply defined feminity, would be the comrade of a man, because she does not regard him as some sort of idol but rather as a companion! Such girls will then, by necessity, carry the values of National Socialism into the next generation as the mental bulwark of our people.

(3) G. Zienef, Education for Death (1942)

A subsequent visit to an ivy-covered school for older girls in Berlin, Westend, about ten blocks from the American School, gave me further information about this domestic-economy curriculum. When I arrived, the schoolyard was crowded with girls. They looked serious as old women. Most of them were jumping, running, marching to the tunes of Nazi songs, to make their bodies strong for motherhood. Some were talking about Party duties, and the latest decrees of their Youth Leader, Frau Gertrud Scholtz-Klink.

A whistle shrilled and the girls gathered about an elevated platform. A Gruppenleiterin was making announcements. Different groups were assigned duties. Some were to go on hikes over the week end, others were to attend anti-air-raid rehearsals. One of the troops, No 10, was specially honored. It had been selected by the district to represent the school at the annual parade on Hitler's birthday.

Group 4 was selected to attend a graduation ceremony in the Palace's courtyard. Jungmaedel from the district would be promoted to ihe BDM status. A stir of reverence went through the group at the mention of this sacred rite.

For fifteen minutes the girls received minute instructions until each knew exactly what to do and when to do it. There was no whining, no complaining. Everybody seemed eager and happy to follow orders.

(4) Traudl Junge, later Adolf Hitler's personal secretary, was a schoolgirl when the Nazi Party gained power in 1933.

In school and generally it was celebrated as a liberation, that Germany could have hope again. I felt great joy then. It was portrayed at school as a turning point in the fate of the Fatherland. There was a chance that German self-confidence could grow again. The words "Fatherland" and "German people" were big, meaningful words which you used carefully - something big and grand. Before, the national spirit was depressed, and it was renewed, rejuvenated, and people responded very positively.

(5) Richard Grunberger, A Social History of the Third Reich (1971)

The Bund Deutscher Mädel (German Girls' League) was the female counterpart of the Hitler Youth. Up to the age of fourteen girls were known as Young Girls (Jungmädel) and from seventeen to twenty-one they formed a special voluntary organization called Faith and Beauty (Glaube und Schonheit). The duties demanded of Jungmädel were regular attendance at club premises and sports meetings, participation in journeys and camp life.

The ideal German Girls' League type exemplified early nineteenth-century notions of what constituted the essence of maidenhood. Girls who infringed the code by perming their hair instead of wearing plaits or the 'Grechen' wreath of braids had it ceremoniously shaved off as punishment.

(6) Isle McKee was a member of the German League of Girls, later recalled her experiences in her autobiography, Tomorrow the World (1960).

We were told from a very early age to prepare for motherhood, as the mother in the eyes of our beloved leader and the National Socialist Government was the most important person in the nation. We were Germany's hope in the future, and it was our duty to breed and rear the new generation of sons and daughter. These lessons soon bore fruit in the shape of quite a few illegitimate small sons and daughters for the Reich, brought forth by teenage members of the League of German Maidens. The girls felt they had done their duty and seemed remarkably unconcerned about the scandal.

(7) William L. Shirer, The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich (1959)

At eighteen, several thousand of the girls in the Bund Deutscher Mädel (they remained in it until 21) did a year's service on the farms - their so-called 'Land Jahr', which was equivalent to the Labour Service of the young men. Their task was to help both in the house and in the fields. The girls lived sometimes in the farmhouses and often in small camps in rural districts from which they were taken by truck early each morning to the farms.

Moral problems soon arose. Actually, the more sincere Nazis did not consider them moral problems at all. On more than one occasion I listened to women leaders of the Bund Deutscher Mädel lecture their young charges on the moral and patriotic duty of bearing children for Hitler's Reich - within wedlock if possible, but without it if necessary.

(8) Cate Haste, Nazi Women (2001)

For Nazis, the key to the future of the Thousand Year Reich was the allegiance of youth. Hitler professed particular concern for children. He made a point of being filmed with them - at the Berghof, where he played the role of "Uncle Adolf" to the offspring of other leaders, looking unusually at ease as he chatted to them and cuddled them on his knee. It is a chilling picture. With children - and dogs - Hitler appeared relaxed. Other, more formal, photo-opportunities show him surrounded by uniformed young girls and boys, laughing as they look up adoringly at him. It was another aspect of stage-management of the leader cult.The boys' Hitler Youth movement was set up in 1926 and the League of German Girls - the BDM (Bund Deutscher Madel) - established in 1932. As soon as the Nazis came to power, they set about eliminating all other rival youth organizations, just as they Nazified the rest of German life. Within a short time, the Catholic Youth organization was the only group left with a rival claim to young people's loyalty. All existing religious political and other youth groups were taken over, disbanded or banned. In one year the Hitler Youth movement, including girls, had climbed from a membership of 108,000 to more than three and a half million.

The leadership immediately set about organizing youth into a coherent body of loyal supporters. Under Baldur von Schirach, himself only twenty-five at the time, the organization was to net all young people from ages ten to eighteen to be schooled in Nazi ideology and trained to be the future valuable members of the Reich. From the start, the Nazis pitched their appeal as the party of youth, building a New Germany. The leadership was fairly young itself, compared with the elderly, whiskery leaders of the Weimar Republic. Hitler was only forty-three in 1933, and his associates were even younger - Heinrich Himmler was thirty-two, Joseph Goebbels thirty-five and Hermann Goring forty. Hitler intended to inspire youth with a mission, appealing to their idealism and hope....

Girls joined the Jungmadel from age ten to thirteen, and the BDM from fourteen to eighteen. Posters of fresh-faced, smiling young girls in uniform with swastikas in the background proclaimed "All Ten-Year-Olds To Us" or, more menacingly - because this was the intention - "All Ten-Year-Olds Belong To Us!" Young people were schooled in loyalty to the Volk, which excluded all other loyalties, including to the family.

Many parents were disturbed that their young daughters were being swept up in this movement. Hedwig Ertl recalled the evening of 30 January 1933 when Hitler came to power. She was aged ten: "There was a lot of singing and shouting in the streets. I came home inspired by these events, with my copy of Der Sturmer in my hand. And I said to my father, "The Jews are our misfortune." He looked at me in horror and slapped me in the face. It was the first and only time he hit me. And I didn't understand. But later, when he would go to visit her mother's grave, which was near the Memorial To Nazi heroes, and rail under his breath against the Nazis, Hedwig could hardly conceal how ashamed she was of him. She felt that her father didn't understand the significance of this great movement. The BDM had started to alienate daughters from their fathers.

Susanne von der Borch's mother was thoroughly opposed, and tried to deter her daughter: "My mother went early on, before Hitler was elected, to a political rally and she listened to him yelling. She was convinced that something terrible was happening to us. As a child, I could not judge. I was simply besotted by it... "Little Nazi", they called me.'

For many girls, joining the BDM was an act of rebellion against their parents. Susanne von der Borch was "the ideal German girl" - tall, blonde-haired, blue-eyed and mad about sport: "From the first day on, this was my world. It fitted my personality, because I had always been very sporty and I liked being with my friends. And I always wanted to get out of the house. So this was the best excuse for me, I couldn't be at home, because there was always something happening: I had to go riding, or skating, or summer camp. I was never at home." Renate Finckh found consolation in the BDM when her parents became active Nazis: "At home no one really had time for me." She joined, aged ten, and "finally found an emotional home, a safe refuge, and shortly thereafter a space in which I was valued". The summons to girls - "The Führer needs you!" - moved her: "I was filled with pride and joy that someone needed me for a higher purpose." Membership gave her life meaning.

(9) Jutta Rüdiger, speech (24th November, 1937)

German parents! My comrades! Shortly after the Reichsjugendführer appointed me to head the BDM on 24 November 1937, a foreign press article reported that I intended to increase the military education of the girls in the BDM.Those who are familiar with girls’ organizations abroad know that some of the girls still wear shoulder straps and carry sheath knives. In some girls’ organizations, they learn to shoot. Those who know this realize that German girls are among the few who receive no military training. Anyone who maintains the contrary only proves how little he knows about the nature of National Socialism.

The Hitler Youth is today the largest youth organization in the world, and the BDM is the largest girls’ organization. One can understand this only by realizing that our starting point is Adolf Hitler.

Boys are trained to be political soldiers, girls to be strong and brave women who will be the comrades of these political soldiers, and who will later, as wives and mothers, live out and form our National Socialist worldview in their families. They will then raise a new and proud generation.

The foundations of our educational work with girls are worldview and cultural education, athletic training, and social service. It is not enough to provide athletic skills and training in home economics. They should know why they are being trained, and what goals they are to strive for.

Athletic training should not only serve their health, but also be a school that trains the girls in discipline and mastery of their bodies. Even the Jungmädel should learn through play to put themselves second and place themselves in the service of the community. Each German girl is trained in the basics of sports. If she proves particularly capable, a girl may choose the sport for which she is gifted, and after completing her other duties, continue to develop her skills in the Reich Federation for Physical Fitness, under the leadership of the Hitler Youth.

We do not want to produce girls who are romantic dreamers, able only to paint, sing, and dance, or who have only a narrow view of life, but rather we want girls with a firm grasp of reality who are ready to make any sacrifice to serve their ideals. Our Jungmädel, together with their comrades in the Jungvolk, join in the battle against hunger and cold. As they stand for hours outside in the cold with their collecting tins, they demonstrate true socialism [Children were put to work collecting for the Nazi charity].

We also expect that, consistent with the wishes of the Reich Youth Leader, each BDM girl will receive training in home economics. That does not mean that we make the cooking pot the goal of education for girls. The politically aware girl knows that any work, whether in a factory or in the home, is of equal value.

We will continually deepen and strengthen our efforts.

Over time, we will establish worldview training and physical education by age groups. That does not mean that we intend to develop a strict school system, but rather that we wish to encourage spiritual and physical development in the youth in ways appropriate to their ages.

Each year on 20 April, the Führer’s birthday, 10-year-old girls become part of the community by joining the Hitler Youth.

At twelve, the Jungmädel must pass the Jungmädel athletic test, and besides some more physical standards, are to be familiar with organizations and structure of the party and the Hitler Youth. The Jungmädel receives a merit badge, but only when her whole Jungmädel group has passed the test. Through this, even the youngest girl will learn that the greatest goals can only be achieved by the community working together.

At 14, the Jungmädel joins the BDM. Most enter the job market at the same time. As a result, the BDM’s educational activities are strengthened and deepened so that they are suited to employment and practical life. The Reich Youth Leader had established a merit badge for the BDM in bronze for athletic accomplishments that can be won by any girl with average abilities.

This year, a sliver merit badge will also be awarded to especially capable girls 16 and older. Besides increased athletic requirements, its recipients must also achieve the first level of awarded by the German Lifesaving Federation. The girl must also be able to lead a girls’ sports session, and conduct a meeting on worldview matters. The girl must also have completed a BDM health course or joined the air raid association, and participated in a long hike.

At 17, the girl can take a course in health, or continue her work in the air raid association. Typical duties in the BDM include two hours a week: a meeting and athletics. Since many older girls are being trained for jobs, which takes more time, and since some girls would like to take additional courses to further their careers, as of 20 April 1938 girls between 18 and 21 will have only one hour of weekly meetings. Sport training will no longer be required, although girls can volunteer for the Reich Federation for Physical Fitness under the supervision of the Hitler Youth.

Those aged 18 to 21 will henceforth be under special guidelines. As of 20 April, 18-year-old girls will be in separate groups. There will be groups for health service, the air raid association, sports, gymnastics and dance, crafts, and theatre.

Girls with gifts in specific fields can join together in small groups for geographical studies.

The small groups for geographical study are primarily intended for girls with foreign language skills. They will focus on a particular foreign state and its people so that they will be able to serve as translators in youth exchange camps. Their first goal is to advance understanding. If the peoples understand each others’ nature and customs, which women have a decisive role in forming, knowing, and respecting, understanding will be promoted.

The special groups will meet once a month to consider political-worldview issues or cultural training, which will build on what they learned between 10 and 18. It will focus on current affairs. Cultural training will include hone and clothing matters. The special meetings will occur at the time scheduled for the standard meetings.

We hope that these special groups will take girls who have been through the basic BDM training and give them a specialized and deeper knowledge so that they will be able to teach younger girls, be it in health training or, for girls in the sport groups, as sport trainers, releasing where possible their younger comrades for other duties. The girls this year will be put to practical work, and depending on their age, will remain active in the youth movement.

In the future, these participants in the special groups will be the source of leaders, speakers, and trainers. In coming years, this will relieve the shortage of leaders that we still face today. The girls who have served in the Reich Federation for Physical Education over the past year have done so well that the Reich Youth Leader, in cooperation with the Reich Sport Leader, has assigned them to the special BDM sports groups.

(10) Melissa Muller, Traudl Junge (2002)

As in most of the youth groups of the Third Reich, there is hardly any discussion of politics in the Faith and Beauty organization. Its activities concentrate on doing graceful gymnastics and dancing, deliberately cultivating a "feminine line" so as to counter any "boyish" or "masculine" development. In fact this gymnastic dancing is also a way of making use of young women for the purposes of the Party and the state - not, of course, that anyone explicitly tells them so, and Traudl junge herself hears about it for the first time decades after the war. Their artistic commitment is intended to bring these young girls up to be "part of the community", and keep them from turning prematurely to the role of wife and mother; instead, they must continue to devote themselves to "the Fuhrer, the nation and the fatherland". Finally, Faith and Beauty will also qualify some of the rising generation of women for leadership; that is to say for posts in the BDM, the Nazi Women's Association or the Reich Labour Service.

(11) Jutta Rüdiger, head of the German League of Girls, was shocked when she heard a speech given by Heinrich Himmler in 1939.

He (Himmler) said that in the war a lot of men would be killed and therefore the nation needed more children, and it wouldn't be such a bad idea if a man, in addition to his wife, had a girlfriend who would also bear his children. And I must say, all my leaders were sitting there with their hair standing on end. And it went further than that. A soldier wrote to me from the front telling me why I should propagate an illegitimate child.

(12) Hildegard Koch, interviewed by Louis Hagen in 1946.

As time went on more and more girls joined the BDM, which gave us a great advantage at school. The mistresses were mostly pretty old and stuffy. They wanted us to do scripture and, of course, we refused. Our leaders had told us that no one could be forced to listen to a lot of immoral stories about Jews, and so we made a row and behaved so badly during scripture classes that the teacher was glad in the end to let us out.

Of course, this meant another big row with Mother - she was pretty ill at that time and had to stay in bed and she was getting more and more pious and mad about the Bible and all that sort of thing. I had a terrible time with her.

After all, we were the new youth; the old people just had to learn to think in the new way and it was our job to make them see the ideals of the new nationalised Germany. When I told her about the camp with the Hitler Youth she was shocked. Well, suppose a young German youth and a German girl did come together and the girl gave a child to the Fatherland - what was so very wrong in that? When I tried to explain that to her she wanted to stop me going on in the BDM - as if it was her business! Duty to the Fatherland was more important to me and, of course, I took no notice. But the real row with Mother came when the BDM girls refused to sit on the same bench as the Jewish girls at school.

Like Father I could never stick Jews. Long before our classes in race theory I thought they were simply disgusting. They are so fat, they all have flat feet and they can never look you straight in the eye. I could not explain my dislike for them until my leaders told me that it was my sound Germanic instinct revolting against this alien element.

The two Jewish girls in our form were racially typical. One was saucy and forward and always knew best about everything. She was ambitious and pushing and had a real Jewish cheek. The other was quiet, cowardly and smarmy and dishonest; she was the other type of Jew, the sly sort. We knew we were right to have nothing to do with either of them.

In the end we got what we wanted. We began by chalking "Jews out!" or "Jews perish, Germany awake!" on the blackboard before class. Later we openly boycotted them. Of course, they blubbered in their cowardly Jewish way and tried to get sympathy for themselves, but we weren't having any. In the end three other girls and I went to the Headmaster and told him that our Leader would report the matter to the Party authorities unless he removed this stain from the school. The next day the two girls stayed away, which made me very proud of what we had done...

I was the Sports Group Organiser in our Section. I was the best at sports, especially at athletics and swimming. I got the Reich Sports Badge and the Swimming Certificate and came out first in both of them and got a lot of praise from our Leader. Altogether she was pretty pleased with me. When we had any street collections my box was always full first and I worked on the other girls to buck up so that our group always made a good impression wherever we went. In the summer we went to the great ReichYouth meeting. Thousands of boys and girls marched in close formation past the Reich Youth Leader, Baldur von Schirach. He and his staff stood on a dais and gave the salute; the trumpets blew, the Landsknecht drums rolled - it was a terrific moment.

At this parade I was right-hand Flugelmann, as always. The Gau Leader herself had picked me from amongst hundreds of girls. I was half a head taller than the tallest of them and had wonderful long blonde hair and bright blue eyes. I had to step out in front of the others and the Gau Leader pointed to me and said: "That is what a Germanic girl should look like; we need young people like that." Once I was photographed and my picture appeared on the tide page of the BdM journal Das deutsche Mädel. Father was delighted and my comrades were terribly jealous.

Our Gau Leader gave me several talks on the duties of the German woman, whose chief aim in life should be to produce healthy stock. She spoke quite openly. Again I was pointed out as a perfect example of the Nordic woman, for besides my long legs and my long trunk, I had the broad hips and pelvis built for childbearing which are essential for producing a large family. Mother could not understand this at all. She thought talking about such things was disgusting and could not understand the ideals of the BdM at all.

(13) Marianne Gärtner, The Naked Years: Growing up in Nazi Germany (1987)

One day, fittingly enough on Hitler's birthday, my age group was called up and I took the oath: "I promise always to do my duty in the Hitler Youth, in love and loyalty to the Führer." Service in the Hitler Youth, we were told, was an honourable service to the German people. I was, however, not thinking of the Führer, nor of serving the German people, when I raised my right hand, but of the attractive prospect of participating in games, sports, hiking, singing, camping and other exciting activities away from school and the home. A uniform, a badge, an oath, a salute. There seemed to be nothing to it. Not really. Thus, unquestioningly, and as smoothly as one day slips into another, I acquired membership, and forthwith attended meetings, joined ball games and competitions, and took part in weekend hikes; and I thought that whether we were sitting in a circle around a camp fire or just rambling through the countryside and singing old German folk songs...

There were now lectures on national socialism, stories about modern heroes and about Hitler, the political fighter, while extracts from Mein Kampf were used to expound the new racial doctrines. And there was nothing equivocal about the mother-role the Führer expected German women to play.

At one meeting, while addressing us on the desirability of large, healthy families, the team leader raised her voice:

"There is no greater honour for a German woman than to bear children for the Führer and for the Fatherland! The Führer has ruled that no family will be complete without at least four children, and that every year, on his mother's birthday, all mothers with more than four children will be awarded the Mutterkreuz. (Decoration similar in design to the Iron Cross (came in bronze, silver or gold, depending on number of children).

Make-up and smoking emerged as cardinal sins.

"A German woman does not use make-up! Only Negroes and savages paint themselves! A German woman does not smoke! She has a duty to her people to keep fit and healthy! Any questions?"

"Why isn't the Führer married and a father himself?" The question was out before I had time to check myself. It was an innocent question, devoid of any pert insinuation that the Führer ought to practise what he preached. Silence filled the whitewashed room, but the team leader offered neither answer nor reproved the question. She strafed me with a murderous look, then called for attention.

"Now, I want you all to learn the Horst Wessel Lied by next Wednesday. All three verses. And don't forget the rally on Saturday! Make sure your blouses are clean, your shoes polished, your cheeks rosy and your voices bright! Hell Hitler! Dismissed!"

Perhaps not surprisingly, by the time I celebrated my thirteenth birthday, my initial Wanderlied and camping euphoria had gone flat and I felt bored with a movement which not only did not tolerate individualists but expected its members to venerate a flag as if it were God Almighty, and which made me march or stand en bloc for hours, listen to tiresome or inflammatory speeches, sing songs not composed for happy hours or shout Führer, let's have your orders, we are following you!, one of the many slogans which, somehow, went into one ear and out the other.

But being old enough to realise that absenteeism from group and mass meetings, or a negative response to the demands of the movement, would be treated as political maladjustment, I thought it wise not to step out of line. Remember that you are a German! they said, and that there was only One Reich, one people, one Führer!, a motto which, like others, if trumpeted loud and long enough, would often come dangerously close to a Bible truth.

(14) Inge Scholl, The White Rose: Students Against Tyranny (1952)

One morning I heard a girl tell another on the steps of the school, "Now Hitler has taken over the government." The radio and newspapers promised, "Now there will be better times in Germany. Hitler is at the helm."

For the first time politics had come into our lives. Hans was fifteen at the time, Sophie was twelve. We heard much oratory about the fatherland, comradeship, unity of the Volk, and love of country. This was impressive, and we listened closely when we heard such talk in school and on the street. For we loved our land dearly - the woods, the river, the old gray stone fences running along the steep slopes between orchards and vineyards. We sniffed the odor of moss, damp earth, and sweet apples whenever we thought of our homeland. Every inch of it was familiar and dear. Our fatherland - what was it but the extended home of all those who shared a language and belonged to one people. We loved it, though we couldn't say why. After all, up to now we hadn't talked very much about it. But now these things were being written across the sky in flaming letters. And Hitler - so we heard on all sides - Hitler would help this fatherland to achieve greatness, fortune, and prosperity. He would see to it that everyone had work and bread. He would not rest until every German was independent, free, and happy in his fatherland. We found this good, and we were willing to do all we could to contribute to the common effort. But there was something else that drew us with mysterious power and swept us along: the closed ranks of marching youth with banners waving, eyes fixed straight ahead, keeping time to drumbeat and song. Was not this sense of fellowship overpowering? It is not surprising that all of us, Hans and Sophie and the others, joined the Hitler Youth.

We entered into it with body and soul, and we could not understand why our father did not approve, why he was not happy and proud. On the contrary, he was quite displeased with us; at times he would say, "Don't believe them - they are wolves and deceivers, and they are misusing the German people shamefully." Sometimes he would compare Hitler to the Pied Piper of Hamelin, who with his flute led the children to destruction. But Father's words were spoken to the wind, and his attempts to restrain us were of no avail against our youthful enthusiasm.

We went on trips with our comrades in the Hitler Youth and took long hikes through our new land, the Swabian Jura. No matter how long and strenuous a march we made, we were too enthusiastic to admit that we were tired. After all, it was splendid suddenly to find common interests and allegiances with young people whom we might otherwise not have gotten to know at all. We attended evening gatherings in our various homes, listened to readings, sang, played games, or worked at handcrafts. They told us that we must dedicate our lives to a great cause. We were taken seriously - taken seriously in a remarkable way - and that aroused our enthusiasm. We felt we belonged to a large, well-organized body that honored and embraced everyone, from the ten-year-old to the grown man. We sensed that there was a role for us in a historic process, in a movement that was transforming the masses into a Volk. We believed that whatever bored us or gave us a feeling of distaste would disappear of itself. One night, as we lay under the wide starry sky after a long cycling tour, a friend - a fifteen-year-old girl - said quite suddenly and out of the blue, "Everything would be fine, but this thing about the Jews is something I just can't swallow." The troop leader assured us that Hitler knew what he was doing and that for the sake of the greater good we would have to accept certain difficult and incomprehensible things. But the girl was not satisfied with this answer. Others took her side, and suddenly the attitudes in our varying home backgrounds were reflected in the conversation. We spent a restless night in that tent, but afterwards we were just too tired, and the next day was inexpressibly splendid and filled with new experiences. The conversation of the night before was for the moment forgotten. In our groups there developed a sense of belonging that carried us safely through the difficulties and loneliness of adolescence, or at least gave us that illusion.

(15) Statement issued by the German government on 3rd May, 1941.

The Hitlerjugend (HJ) come to you today with the question: why are you still outside the ranks of the HJ? We take it that you accept your Fuehrer, Adolf Hitler. But you can only do this if you also accept the HJ created by him. If you are for the Fuehrer, therefore for the HJ, then sign the enclosed application. If you are not willing to join the HJ, then write us that on the enclosed blank.

(16) Richard Grunberger, A Social History of the Third Reich (1971)

Given this overall educational atmosphere, the Nazi rulers saw little need for radical innovation after the seizure of power; apparent continuity had the dual advantage of conserving resources and reassuring conservative opinion. Thus there was little surface disturbance of the routine of education. Few teachers were dismissed (among those who were, some of the non-Jews were reinstated during the subsequent shortage) and a sizeable proportion of old textbooks remained in use for the time being. One drastic new departure, which, however, only affected the top strata of the school population, stemmed from the regime's law against the overcrowding of German schools and universities, which in January 1934 froze the female share of diminishing university places at 10 per cent. At the academic level the resultant contraction was quite drastic. By the outbreak of war, university enrolment as such had declined by almost three fifths and the number of grammar-school pupils had been reduced by under one fifth.

Within the grammar-school population, the proportion of girls was reduced from 35 per cent to 30 per cent. In 1934 only 1,500 out of 10,000 girls who had taken the Abitur were allowed to proceed to university, and up to the outbreak of war the number of girls taking the school-leaving examination remained well below the pre-1933 average? When new boarding-schools for rearing a Nazi elite (the Nationalpolitische Erziehungsanstalten or National Political Educational Establishments - "Napolas" for short) were set up, the allocation of places for girls was given such low priority that only two out of thirty-nine Napolas constructed before the outbreak of war catered for them.

Girls staying on at higher schools were shunted into either domestic-science or language streams, the former leading up to an examination that became derisively known as "Pudding Matric", and represented an academic dead-end. The inadequacy of these arrangements occasioned widespread discontent. In 1941 girls who had obtained the "Pudding Matric" at last became eligible for university studies in the same way as their colleagues who had gone through the language stream. So keen was the competition for the limited academic career opportunities available that sixth-formers on occasion even resorted to denouncing classmates to the Gestapo.

Student Activities

Adolf Hitler's Early Life (Answer Commentary)

Heinrich Himmler and the SS (Answer Commentary)

Trade Unions in Nazi Germany (Answer Commentary)

Adolf Hitler v John Heartfield (Answer Commentary)

Hitler's Volkswagen (The People's Car) (Answer Commentary)

Women in Nazi Germany (Answer Commentary)

The Assassination of Reinhard Heydrich (Answer Commentary)