Sophie Scholl

Sophie Scholl, the daughter of Robert Scholl and Magdalena Scholl, was born in Forchtenberg on 9th May, 1921. Her father was elected mayor of Forchtenberg. (1) Over the next few years he managed to get the railway extended to the town. He also had a community sports centre built in Forchtenberg but he was considered to be too progressive for some and in 1930 he was voted out of office. (2)

The family moved to Ulm in 1932. "Robert Scholl had lived in several small towns in Swabia, an area of south-west Germany known for its rural charms, thrifty people, and spirit of independence, before settling in Ulm, where he opened his own office as a tax and business consultant. He was a big, rather heavyset man, with strong opinions and an unwillingness, if not an inability, to keep those opinions to himself." (3)

Sophie was very close to her sisters and brothers, Inge (b. 1917) Hans (b. 1918), Elisabeth (b. 1920), Werner (b. 1922) and Thilde (b. 1925). "The Scholl children were seldom seen tumbling about the streets and were never heard singing improper songs in public. A close-knit clan with a strong sense of each other, they usually provided themselves with enough companionship to make a presence of outsiders unnecessary." (4)

Sophie Scholl and the German League of Girls

Robert Scholl was a strong opponent of Adolf Hitler and was very upset when Hans joined the Hitler Youth and Sophie Inge and Elisabeth became members of the German League of Girls (BDM) in 1933. He argued against Hitler and the Nazi Party and disagreed with his children's views that he would reduce unemployment: "Have you considered how he's going to manage it? He's expanding the armaments industry, and building barracks. Do you know where that's all going to end." (5)

Elisabeth Scholl later pointed out why they rejected their father's advice: "We just dismissed it: he's too old for this stuff, he doesn't understand. My father had a pacifist conviction and he championed that. That certainly played a role in our education. But we were all excited in the Hitler youth in Ulm, sometimes even with the Nazi leadership." (6) Sophie approached BDM with "girlish enthusiasm" but thought it absurd that her Jewish friend, Luise, was not allowed to join. (7)

Sophie became a BDM group leader. Susanne Hirzel later recalled: "I got to know Sophie Scholl when she was my group leader in the BDM. I admired her because of her eloquence and her behavior and she quickly became my very best friend. I often stayed at Sophie's parents' home and got to know her brother Hans and her sister Inge. The BDM was a scouting organization for girls. Political indoctrination was only one aspect among many others and I even became a troop leader(Scharführerin). Sophie's father Robert Scholl was a determined... pacifist and a sincere Christian. He told us about his experiences and that influenced my thinking." (8)

Inge Scholl later recalled what life was like in the BDM: "We heard much oratory about the fatherland, comradeship, unity of the Volk, and love of country.... Our fatherland - what was it but the extended home of all those who shared a language and belonged to one people. We loved it, though we couldn't say why. After all, up to now we hadn't talked very much about it. But now these things were being written across the sky in flaming letters. And Hitler - so we heard on all sides - Hitler would help this fatherland to achieve greatness, fortune, and prosperity. He would see to it that everyone had work and bread. He would not rest until every German was independent, free, and happy in his fatherland. We found this good, and we were willing to do all we could to contribute to the common effort. But there was something else that drew us with mysterious power and swept us along: the closed ranks of marching youth with banners waving, eyes fixed straight ahead, keeping time to drumbeat and song.... We entered into it with body and soul, and we could not understand why our father did not approve, why he was not happy and proud. On the contrary, he was quite displeased with us." (9)

Scholl held liberal opinions and allowed his children to make their own choices. According to Richard F. Hanser: "They could say whatever they wished, and they all had opinions. This was far from customary practice in German households, where, by long tradition, the authority of the father was seldom questioned or his statements challenged... His aversion to mindless nationalism was not only unchanged but stronger than before. In his dinner-table discussions with his children, he could interpret events for them with an insight unblurred by current prejudices or official pronouncements." (10)

In September 1936 David Lloyd George visited Nazi Germany. On his return to Britain he wrote: "I have just returned from a visit to Germany. ... I have now seen the famous German leader and also something of the great change he has effected.... One man has accomplished this miracle. He is a born leader of men. A magnetic dynamic personality with a single-minded purpose, a resolute will, and a dauntless heart. He is the national Leader. He is also securing them against that constant dread of starvation which is one of the most poignant memories of the last years of the war and the first years of the Peace. The establishment of a German hegemony in Europe which was the aim and dream of the old prewar militarism, is not even on the horizon of Nazism. (11)

Hans Scholl, now a local leader of the Hitler Youth, used Lloyd George's comments to defend Hitler against his father. "Why, the Führer is even being praised abroad! Here in the paper is an interview with Lloyd George, Britain's prime minister during the last war. He calls Hitler a great leader. He says he wishes that England had a statesman of her own like him." Robert Scholl replied: "I know the Nazis better than Lloyd George does. Believe me, they are wolves and wild beasts, and they are misusing the German people abominably." (12)

Sophie Scholl membership of the German League of Girls (BDM) caused problems for her father but she remained close to him: "Sophie's relationship with Robert Scholl held a depth of mutual understanding... it continued to exist despite the pain she caused her father by joining the BDM - she could observe his distress when he watched Party displays on the cathedral square outside their Ulm window, or when he argued with Hans - her father had not tried to prevent her from joining. He knew that opponents to tyranny could never be created by force, only by personal experience." (13) Sophie eventually became a Group Leader of the BDM. (14)

Disillusionment with Adolf Hitler

Sophie's brother, Hans Scholl, was chosen to be the flag bearer when his unit attended the Nuremberg Rally in 1936. His sister, Inge Scholl, later recalled: "His joy was great. But when he returned, we could not believe our eyes. He looked tired and showed signs of a great disappointment. We did not expect any explanation from him, but gradually we found out that the image and model of the Hitler Youth which had been impressed upon him there was totally different from his own ideal... Hans underwent a remarkable change... This had nothing to do with Father's objections; he was able to close his ears to those. It was something else. The leaders had told him that his songs were not allowed... Why should he be forbidden to sing these songs that were so full of beauty? Merely because they had been created by other races?" (15)

Sophie was very close to Hans and she also became disillusioned with Adolf Hitler. Shortly after Hans returned from Nuremberg, an important BDM leader arrived from Stuttgart to conduct an evening of ideological training for the girls in Ulm. When the members were asked if they had any preferences for discussion, Sophie suggested they read poems by Heinrich Heine, one of her favourite writers. The leader was appalled and pointed out that the left-wing, anti-war, Jewish writer, had his books burned and banned by Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels in 1933. Apparently, Sophie replied, "Whoever doesn't know Heine, does not know German literature." (16)

Elisabeth Scholl has argued that during this period all the Scholl children gradually became hostile to the government. They were undoubtedly influenced by the views of their parents but had been disappointed by the reality of living in Nazi Germany: "First, we saw that one could no longer read what one wanted to, or sing certain songs. Then came the racial legislation. Jewish classmates had to leave school." (17)

Sophie's 19-year-old sister, Inge Scholl, was also beginning to question the policies of the Nazi government. "We went on trips with our comrades in the Hitler Youth and took long hikes through our new land, the Swabian Jura.... We attended evening gatherings in our various homes, listened to readings, sang, played games, or worked at handcrafts. They told us that we must dedicate our lives to a great cause.... One night, as we lay under the wide starry sky after a long cycling tour, a friend - a fifteen-year-old girl - said quite suddenly and out of the blue, Everything would be fine, but this thing about the Jews is something I just can't swallow. The troop leader assured us that Hitler knew what he was doing and that for the sake of the greater good we would have to accept certain difficult and incomprehensible things. But the girl was not satisfied with this answer. Others took her side, and suddenly the attitudes in our varying home backgrounds were reflected in the conversation. We spent a restless night in that tent, but afterwards we were just too tired, and the next day was inexpressibly splendid and filled with new experiences." (18)

A Nazi Education

Sophie Scholl also began having trouble at school. Teachers who did not support the Nazi Party had been sacked. One girl who successfully left Nazi Germany when she was sixteen later wrote: "Teachers had to pretend to be Nazis in order to remain in their posts, and most of the men teachers had families which depended on them. If somebody wanted to be promoted he had to show what a fine Nazi he was, whether he really believed what he was saying or not. In the last two years, it was very difficult for me to accept any teaching at all, because I never knew how much the teacher believed in or not." (19)

Effie Engel, who went to school in Dresden, pointed out: "The progressive teachers in our school all left and we got a number of new teachers. In my last two years of school, we got some teachers who had already been reprimanded. The fascists allowed them to be reinstated if they thought they were no longer compromised by anything else. But I also knew two teachers who never got a job again in the entire Hitler period.... One of the new teachers was in the SA and came to school in his uniform. I couldn't stand him. In part, we couldn't stand him because he was so loud and crude." (20)

One of the most popular teachers at Sophie's school disappeared. None of the other teachers were willing to say what had happened to him. Rumours claimed he was hauled up before a squad of Storm Troopers who paraded past him, each one spitting in his face on command in passing. When her mother, Magdalena Scholl, asked what offence he had committed, she was told "Nothing! Nothing at all! He refused to become a Nazi. He wouldn't conform. He couldn't bring himself to go along with them. That was his crime." (21)

Teachers encouraged members of the Hitler Youth to inform on their parents. For example, they set essays entitled "What does your family talk about at home?" According to one source: "Parents... were alarmed by the gradual brutalisation of manners, impoverishment of vocabulary and rejection of traditional values... Their children became strangers, contemptuous of monarchy or religion, and perpetually barking and shouting like pint-sized Prussian sergeant-majors." (22)

Sophie Scholl would never have informed on her father. She also began to question the Nazi-trained teachers. As Richard F. Hanser, the author of A Noble Treason: The Story of Sophie Scholl (1979), has pointed out: "Her zest gradually diminished as it became more and more clear that the BDM, like all other National Socialist programs, was designed for conformity rather than liberation. The three K's that traditionally marked off the boundaries for the German female - Kinder, Kuche, Kirche (children, kitchen, and church) - would remain fully in force under the Nazis, despite the exertions of the Ideological Training Division to persuade everyone that a new day had dawned. The shoulder-to-shoulder marching, the continual sloganeering that emphasized the group rather than the individual, came to have a suffocating effect on Sophie, who always had a sure sense of herself that she never wholly lost even when the marching, singing, and saluting were at their height. The constant pressure to give herself over to organized activity became less and less tolerable." (23)

Arrest of the Scholl Family

Hans Scholl and some of his friends decided to form their own youth organization. Inge Scholl later recalled: "The club had its own most impressive style, which had grown up out of the membership itself. The boys recognized one another by their dress, their songs, even their way of talking... For these boys life was a great, splendid adventure, an expedition into an unknown, beckoning world. On weekends they went on hikes, and it was their way, even in bitter cold, to live in a tent... Seated around the campfire they would read aloud to each other or sing, accompanying themselves with guitar, banjo, and balalaika. They collected the folk songs of all peoples and wrote words and music for their own ritual chants and popular songs." (24)

At the age of nineteen, every German, male or female, had to spend six months on a construction project or a farm. The National Labour Service was an attempt to keep the young under the supervision of government agencies as long as possible. It also removed thousands from the labour market and therefore reduced the unemployment statistics and kept young people off the streets where they might cause trouble. (25) Hans Scholl was assigned to road building near a place called Göppingen. The project was part of the Autobahn system, the network of roads across Germany, which was one of Hitler's most valued programs. (26)

Six months of National Labour Service was followed by conscription into the German Army. Hans always loved horses and he volunteered and was accepted for a cavalry unit in 1937. A few months later he was arrested in his barracks by the Gestapo. Apparently, it had been reported that while living in Ulm he had been taking part in activities that were not part of the Hitler Youth program. Sophie, Inge and Werner Scholl were also arrested. (27)

As Sophie was only sixteen, she was released and allowed to go home the same day. One biographer has pointed out: "She seemed too young and girlish to be a menace to the state, but in releasing her the Gestapo was letting slip a potential enemy with whom it would later have to reckon in a far more serious situation. There is no way of establishing the precise moment when Sophie School decided to become an overt adversary of the National Socialist state. Her decision, when it came, doubtless resulted from the accretion of offences, small and large, against her conception of what was right, moral, and decent. But now something decisive had happened. The state had laid its hands on her and her family, and now there was no longer any possibility of reconciling herself to a system that had already begun to alienate her." (28)

The Gestapo searched the Scholl house and confiscated diaries, journals, poems, essays, folk song collections, and other evidence of being members of an illegal organisation. Inge and Werner were released after a week of confinement. Hans was detained three weeks longer while the Gestapo attempted to persuade him to give damaging information about his friends. Hans was eventually released after his commanding officer had ensured the police that he was a good and loyal soldier. (29)

The Second World War

Sophie Scholl now became a much more difficult student at school. On several occasions she upset her teachers with her candid comments that ran counter to the prevailing Nazi doctrine. More than once she was summoned before the principal of the school and warned that unless her attitude changed she would be barred from taking her university entrance exams. (30)

Elisabeth Scholl remembers a conversation she had with Sophie in the summer of 1939: "As time went on Sophie became increasingly disillusioned with the Nazis. On the day before England declared war in 1939 I went with her for a walk along the Danube and I remember I said: Hopefully there will be no war. And she said: Yes, I hope there will be. Hopefully someone will stand up to Hitler. In this she was more decisive than Hans." (31)

On the outbreak of the Second World War, her boyfriend Fritz Hartnagel, was serving in the German Army and a loyal supporter of Adolf Hitler. She wrote to him expressing her bitterness: "Now you'll surely have enough to do. I can't grasp that now human beings will constantly be put into mortal danger by other human beings. I can never grasp it, and I find it horrible. Don't say it's for the Fatherland." (32)

After leaving school in 1940 Sophie became a kindergarten teacher at the Frobel Institute in Ulm-Söflingen. During this period Sophie became very interested in politics. Sophie wrote to her boyfriend: "If I didn't know that I'll probably outlive many older people then I'd be overcome with horror at the spirit that's dominating history today... I'm sure you find what I'm writing very unfeminine. It's ridiculous for a girl to involve herself in politics. She should let her feminine feelings dominate her thoughts. Especially compassion. But I believe that first comes thinking, and that feelings, especially about little things that affect you directly, maybe about your own body, deflect you so that you can hardly see the big things anymore." (33)

Sophie continued to take risks by criticising the government. Her sister Inge Scholl later recalled: "We were living in a society where despotism, hate, and lies had become the normal state of affairs. Every day that you were not in jail was like a gift. No one was safe from arrest for the slightest unguarded remark, and some disappeared forever for no better reason... Hidden ears seemed to be listening to everything that was being spoken in Germany. The terror was at your elbow wherever you went." (34)

Sophie became convinced that it was time for German citizens to begin rebelling against the Nazi government. She told her boyfriend, Fritz Hartnagel: "For me the relationship between a soldier and his people is roughly like that of a son who swears to stand by his father and his family through thick and thin. If it turns out that the father harms another family and then gets hurt as a consequence, must the son still stick by him? I can't accept it. Justice is more important than sentimental loyalty." (35)

Sophie passed her entrance exams and in early 1941 she wrote in her diary that she hoped that she would be allowed to study with her brother Hans at the University of Munich. "Wouldn't it be wonderful if Hans and I could study together for a time? We're already bursting with plans!" However, the authorities insisted that all female high-school graduates serve at least six months in the National Labour Service and she became a nursery teacher in Blumberg. It was not a happy time for Sophie. "Blumberg was a small and unattractive industrial town. It was hard for Sophie to find any saving graces here, even though she did become fond of the children. But her chores were menial and exhausting, and laboured, she was aware always that her work helped indirectly to perpetuate a war she deplored, conducted by a regime she had gradually come to consider criminal." (36)

Whenever possible Sophie would return to Ulm to be with her brother Hans when he was on leave from the army. They discussed together their feelings about the Nazi government. Hans was especially critical of the lack of protest from the Christian leadership in Germany concerning the crimes of the government: "What are we going to have to show in the way of resistance - as compared to the Communists, for instance - when this terror is over? We will be standing there empty-handed. We will have no answer when we are asked: What did you do about it?" (37)

Fritz Hartnagel came home on leave in late 1941. He was shocked by the changes that had taken place in Sophie concerning the war. "She was striking to see with what incisiveness and logic Sophie saw how things would develop, for she was warm-hearted and full of feeling, not cold and calculating... There was a big propaganda campaign in Germany to get the people to give sweaters and other warm woollen clothing to the Army. German soldiers were at the gates of Leningrad and Moscow in the middle of a winter war for which they weren't prepared... Sophie said, We're not giving anything. I had just got back from the Russian Front... I tried to describe to her how conditions were for the men, with no gloves, pullovers or warm socks. She stuck to her viewpoint relentlessly and justified it by saying, It doesn't matter if it's German soldiers who are freezing to death or Russians, the case is equally terrible. But we must lose the war. If we contribute warm clothes, we'll be extending it." (38)

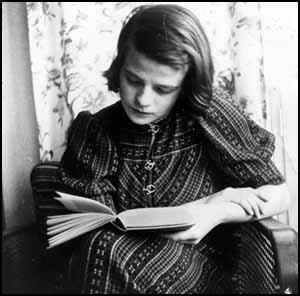

In May 1942, Sophie entered the University of Munich where she became a student of biology and philosophy. Inge Scholl later recalled the day she left for university: "I still see her as she stood before me, my sister... ready to start and full of expectation. At her temple she wore a yellow daisy, retrieved from the birthday table. It was beautiful to see her dark, smooth, shiny hair hang down to her shoulders. With her large brown eyes she looked upon the world critically but with lively interest. Hers was still a child's face, with delicate features. In it there was something akin to the nervous curiosity of a young animal and at the same time an expression of great seriousness." (39)

Sophie Scholl was greatly influenced by Kurt Huber, her philosophy teacher. In his lectures on Immanuel Kant, Huber argued that he was a great moralist who believed that all human beings had the ability to reason and ought to have the freedom to exercise this ability. Reason, not accepting the orders of authority, was the basis of morality. "In his own time Kant had opposed all forms of unthinking obedience, repeatedly claiming that independent, rational thought was the basis of all good conduct." (40)

Sophie's boyfriend, Fritz Hartnagel, was now serving in the Soviet Union and had taken part in the fighting in Stalingrad. Elisabeth Scholl later explained: "In the letters home to Sophie he wrote about how horrified he was at the shooting of Jews. Then there was the architect Manfred Eickemeyer who provided Hans with use of studio in Munich while he was in Poland. Eickemeyer told him about the executions of Jews and the Polish intelligentsia." (41)

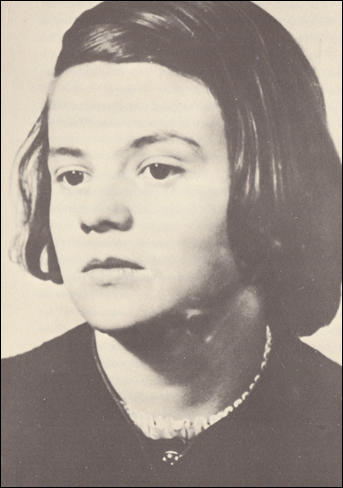

There is a photograph of Sophie Scholl that was taken on 23rd July, 1942 (see below). Richard F. Hanser, the author of A Noble Treason: The Story of Sophie Scholl (1979) has pointed out: "They are all standing next to an openwork iron fence whose top reaches only a few inches over their heads. Peering down at them over the fence is Sophie, who is standing on something on the other side. She has evidently been there for some time. Her satchel-like briefcase, probably filled with books, is hooked by its handles to one of the fence spikes. She is wearing a knitted sweater with broad stitches, and her dark hair is falling loosely to her shoulders.... In one of the photographs, her lifted arms are flung wide, and there is a correspondingly wide smile on her face. It is a light and girlish gesture at a time that could not have been happy for her." (42)

In July 1942, Hans Scholl and his student friends, Christoph Probst, Alexander Schmorell and Willi Graf, were sent to the Eastern Front as medics. During their time in Poland and the Soviet Union they witnessed many examples of atrocities being committed by the German Army which made them even more hostile to the government. They were also upset by having to treat so many wounded and dying soldiers. It became clear that Germany was fighting a war it could not win. (43)

Hans Scholl later told his sister Inge about one incident that had a profound impact on him. "During the transport to the front their train had stopped for a few minutes at a Polish station. Along the embankment he saw women and girls bent over and doing heavy men's work with picks. They wore the yellow Star of David on their blouses. Hans slipped through the window of his car and approached. The first one in the group was a young, emaciated girl with small, delicate hands and a beautiful, intelligent face that bore an expression of unspeakable sorrow. Did he have anything that he might give to her? He remembered his Iron Ration - a bar of chocolate, raisins, and nuts - and slipped it into her pocket. The girl threw it on the ground at his feet with a harassed but infinitely proud gesture. He picked it up, smiled, and said, I wanted to do something to please you. Then he bent down, picked a daisy, and placed it and the package at her feet. The train was starting to move, and Hans had to take a couple of long leaps to get back on. From the window he could see that the girl was standing still, watching the departing train, the white flower in her hair." (44)

In August 1942 Robert Scholl was arrested by the Gestapo. He was reported by a young woman in his office as saying in reply to a question about the progress of the war: "The war! It is already lost. This Hitler is God's scourge on mankind, and if the war doesn't end soon, the Russians will be sitting in Berlin." The woman was asked by a friend what she had against Robert Scholl. She replied: "Nothing. I liked him. I had to suppress my personal feelings. I was fond of Herr Scholl, and I was grateful to him, but when he said those things about the Führer and the war, I knew I couldn't let it pass." (45) Scholl was eventually sentenced to four months in prison. (46)

White Rose Group

Hans Scholl had fought in France in 1940 but had been allowed to train as a doctor at the University of Munich. He soon made friends with other medical students who also questioned the morality of the Nazi government. This included Christoph Probst, Alexander Schmorell, Willi Graf, and Jugen Wittenstein. These men were introduced to Sophie when she arrived at university. (47)

The group of friends had discovered a professor at the university who shared their dislike of the Nazi regime. Kurt Huber was Sophie's philosophy teacher. However, medical students also attended his lectures, which "were always packed, because he managed to introduce veiled criticism of the regime into them". (48) The 49 year-old professor, also joined in private discussions with what became known as the White Rose group. Hans told his sister, Inge Scholl, "though his hair was turning grey, he was one of them". (49)

According to Elisabeth Scholl, the White Rose group was formed because of the execution of members of the resistance: "We learned in the spring of 1942 of the arrest and execution of 10 or 12 Communists. And my brother said, In the name of civic and Christian courage something must be done. Sophie knew the risks. Fritz Hartnagel told me about a conversation in May 1942. Sophie asked him for a thousand marks but didn’t want to tell him why. He warned her that resistance could cost both her head and her neck. She told him, I’m aware of that. Sophie wanted the money to buy a printing press to publish the anti-Nazi leaflets” (50)

The White Rose group began producing leaflets. They were typed single-spaced on both sides of a sheet of paper, duplicated, folded into envelopes with neatly typed names and addresses, and mailed as printed matter to people all over Munich. At least a couple of hundred were handed into the Gestapo. It soon became clear that most of the leaflets were received by academics, civil servants, restaurateurs and publicans. A small number were scattered around the University of Munich campus. As a result the authorities immediately suspected that students had produced the leaflets. (51)

The opening paragraph of the first leaflet said: "Nothing is so unworthy of a civilized nation as allowing itself to be "governed" without opposition by an irresponsible clique that has yielded to base instinct. It is certain that today every honest German is ashamed of his government. Who among us has any conception of the dimensions of shame that will befall us and our children when one day the veil has fallen from our eyes and the most horrible of crimes - crimes that infinitely outdistance every human measure-reach the light of day? If the German people are already so corrupted and spiritually crushed that they do not raise a hand, frivolously trusting in a questionable faith in lawful order in history; if they surrender man's highest principle, that which raises him above all other God's creatures, his free will; if they abandon the will to take decisive action and turn the wheel of history and thus subject it to their own rational decision; if they are so devoid of all individuality, have already gone so far along the road toward turning into a spiritless and cowardly mass - then, yes, they deserve their downfall." (52)

According to the historian of the resistance, Joachim Fest, this was a new development in the struggle against Adolf Hitler. "A small group of Munich students were the only protesters who managed to break out of the vicious circle of tactical considerations and other inhibitions. They spoke out vehemently, not only against the regime but also against the moral indolence and numbness of the German people." (53) Peter Hoffmann, the author of The History of German Resistance (1977) claimed they must have been aware that they could do any significant damage to the regime but they "were prepared to sacrifice themselves" in order to register their disapproval of the Nazi government. (54)

The second leaflet was published in the third week of June 1942 dealt with the treatment of Jews in Nazi Germany and in Eastern Europe. "Since the conquest of Poland three hundred thousand Jews have been murdered in this country in the most bestial way. Here we see the most frightful crime against human dignity, a crime that is unparalleled in the whole of history. For Jews, too, are human beings - no matter what position we take with respect to the Jewish question - and a crime of this dimension has been perpetrated against human beings. Someone may say that the Jews deserved their fate. This assertion would be a monstrous impertinence; but let us assume that someone said this - what position has he then taken toward the fact that the entire Polish aristocratic youth is being annihilated? (May God grant that this program has not fully achieved its aim as yet!) All male offspring of the houses of the nobility between the ages of fifteen and twenty were transported to concentration camps in Germany and sentenced to forced labor, and all girls of this age group were sent to Norway, into the bordellos of the SS!"

The leaflet then raised questions about the way the German population were responding to these atrocities: "Why tell you these things, since you are fully aware of them - or if not of these, then of other equally grave crimes committed by this frightful sub-humanity? Because here we touch on a problem which involves us deeply and forces us all to take thought. Why do the German people behave so apathetically in the face of all these abominable crimes, crimes so unworthy of the human race? Hardly anyone thinks about that. It is accepted as fact and put out of mind. The German people slumber on in their dull, stupid sleep and encourage these fascist criminals; they give them the opportunity to carry on their depredations; and of course they do so. Is this a sign that the Germans are brutalized in their simplest human feelings, that no chord within them cries out at the sight of such deeds, that they have sunk into a fatal consciencelessness from which they will never, never awake? It seems to be so, and will certainly be so, if the German does not at last start up out of his stupor, if he does not protest wherever and whenever he can against this clique of criminals, if he shows no sympathy for these hundreds of thousands of victims. He must evidence not only sympathy; no, much more: a sense of complicity in guilt. For through his apathetic behavior he gives these evil men the opportunity to act as they do; he tolerates this government which has taken upon itself such an infinitely great burden of guilt; indeed, he himself is to blame for the fact that it came about at all! " (55)

The third leaflet claimed that the goal of the White Rose was to bring down the Nazi government. It suggested the strategy of passive resistance that was being used by students fighting against racial discrimination in the United States: "We want to try and show them that everyone is in a position to contribute to the overthrow of the system. It can be done only by the cooperation of many convinced, energetic people - people who are agreed as to the means they must use. We have no great number of choices as to the means. The only one available is passive resistance. The meaning and goal of passive resistance is to topple National Socialism, and in this struggle we must not recoil from our course, any action, whatever its nature. A victory of fascist Germany in this war would have immeasurable, frightful consequences. The first concern of every German is not the military victory over Bolshevism, but the defeat of National Socialism." (56)

This leaflet was sent to Sophie's philosophy teacher, Kurt Huber. He was then invited to the home of Alexander Schmorell, one of the people who produced the leaflet. He turned up but was reluctant to get involved in a discussion about resisting the Nazi government. He was strongly anti-communist and was unhappy with the passage in the leaflet that said: "The first concern of every German is not the military victory over Bolshevism, but the defeat of National Socialism." He left the meeting without making it clear if he was willing to join the group. (57)

The group needed funds for the printing and mailing of the leaflets. Fritz Hartnagel who was on leave, gave Sophie 1,000 Reichsmarks, for what she told him was "a good purpose". Falk Harnack, a member of the Red Orchestra resistance group, also provided help. As well as sending the leaflets in the mail, members of the group carried them in suitcases to towns in southern Germany and delivering them to their supporters. This was highly dangerous as the Gestapo often carried out searches of passengers in trains. As a result of this activity, resistance groups were set up in Hamburg and Berlin. (58)

A fourth leaflet was published in July 1942. It included detailed of the large number of German soldiers killed during Operation Barbarossa: "Neither Hitler nor Goebbels can have counted the dead. In Russia thousands are lost daily. It is the time of the harvest, and the reaper cuts into the ripe grain with wide strokes. Mourning takes up her abode in the country cottages, and there is no one to dry the tears of the mothers. Yet Hitler feeds with lies those people whose most precious belongings he has stolen and whom he has driven to a meaningless death." The ended the leaflet with the words: "We will not be silent. We are your bad conscience. The White Rose will not leave you in peace!" (59)

For a time Sophie Scholl thought she was in love with Alexander Schmorell. However, in October, 1942, she wrote in her diary: "What false dreams people can create for themselves! Months ago I was still thinking my feelings for Shurik (Schmorell) were greater than for anyone else. But this was such a false delusion! It was only my vanity that wanted to possess a person who had value in the eyes of others. I distort my own self-image in a ridiculous way." (60)

In December 1942, Hans Scholl went to visit Kurt Huber and asked his advice on the text of a new leaflet. He had previously rejected the idea of leaflets because he thought they would have no appreciable effect on the public and the danger of producing them outweighed any effect they might have. However, he had changed his mind and agreed to help Scholl write the leaflet. (61) Huber later commented that "in a state where the free expression of public opinion is throttled a dissident must necessarily turn to illegal methods." (62)

The first draft of the fifth leaflet was written by Sophie and Hans Scholl and Alexander Schmorell. (63) Kurt Huber then revised the material. The three men had long discussions about the content of the leaflet. Huber thought that the young men were "leaning too much to the left" and he described the White Rose group as "a Communist ring". (64) However, it was eventually agreed what would be published. For the first time, the name White Rose did not appear on the leaflet. The authors now presented them as the "Resistance Movement in Germany". (65)

This leaflet, entitled A Call to All Germans!, included the following passage: "Germans! Do you and your children want to suffer the same fate that befell the Jews? Do you want to be judged by the same standards as your traducers? Are we do be forever the nation which is hated and rejected by all mankind? No. Dissociate yourselves from National Socialist gangsterism. Prove by your deeds that you think otherwise. A new war of liberation is about to begin."

It ended with the kind of world they wanted after the war finished: "Imperialistic designs for power, regardless from which side they come, must be neutralized for all time... All centralized power, like that exercised by the Prussian state in Germany and in Europe, must be eliminated... The coming Germany must be federalistic. The working class must be liberated from its degraded conditions of slavery by a reasonable form of socialism... Freedom of speech, freedom of religion, the protection of individual citizens from the arbitrary will of criminal regimes of violence - these will be the bases of the New Europe." (66)

The Gestapo later estimated that the White Rose group distributed around 10,000 copies of this leaflet. Sophie Scholl and Traute Lafrenz purchased the special paper needed, as well as the envelopes and stamps from a large number of shops to avoid suspicion. Each leaflet was turned out one by one, night after night. "In order to stay awake and to function during the day, they took pep pills from the military clinics where the medics worked." (67) The conspirators had to ensure that the Gestapo could not trace the source to Munich so the group had to post their leaflets from neighbouring towns." (68)

The authorities took the fifth leaflet more seriously than the others. One of the Gestapo's most experienced agents, Robert Mohr, was ordered to carry out a full investigation into the group called the "Resistance Movement in Germany". He was told "the leaflets were creating the greatest disturbance at the highest levels of the Party and the State". Mohr was especially concerned by the leaflets simultaneous appearance in widely separated cities including Stuttgart, Vienna, Ulm, Frankfurt, Linz, Salzburg and Augsburg. This suggested an organization of considerable size was at work, one with capable leadership and considerable resources. (69)

Arrest and Execution

On 13th January, 1943, the Gauleiter of Bavaria, Paul Giesler, addressed the students of University of Munich in the Main Auditorium of the Deutsche Museum. He argued that universities should not produce students with "twisted intellects" and "falsely clever minds". Giesler went on to state that "real life is transmitted to us only by Adolf Hitler, with his light, joyful and life-affirming teachings!" He went on to attack "well-bred daughters" who were shirking their war duties. Some women in the audience began calling out angry comments. He responded by arguing that "the natural place for a woman is not at the university, but with her family, at the side of her husband." The female students at the university should fulfill their duties as mothers instead of studying. He then added that "for those women students not pretty enough to catch a man, I'd be happy to lend them one of my adjutants". (70)

Women students began shouting abuse at Giesler. He then ordered their arrest by his SS guards. Male students came to their aid and fights began all over the auditorium. Those who managed to escape ran out of the museum and after forming themselves in a large group, began marching in a procession in the direction of the university. They linked arms as they marched singing songs of solidarity. However, before they got to the university armed police forced them to disperse. (71)

The White Rose group believed there was a direct connection between their leaflets and the student unrest. They decided therefore to print another 1,300 leaflets and to distribute them around the university. On 18th February, 1943, Sophie and Hans Scholl arrived at the University of Munich with a suitcase packed with leaflets. According to Inge Scholl: "They arrived at the university, and since the lecture rooms were to open in a few minutes, they quickly decided to deposit the leaflets in the corridors. Then they disposed of the remainder by letting the sheets fall from the top level of the staircase down into the entrance hall. Relieved, they were about to go, but a pair of eyes had spotted them. It was as if these eyes (they belonged to the building superintendent) had been detached from the being of their owner and turned into automatic spyglasses of the dictatorship. The doors of the building were immediately locked, and the fate of brother and sister was sealed." (72)

Jakob Schmid, a member of the Nazi Party, saw them at the University of Munich, throwing leaflets from a window of the third floor into the courtyard below. He immediately told the Gestapo and they were both arrested. They were searched and the police found a handwritten draft of another leaflet. This they matched to a letter in Scholl's flat that had been signed by Christoph Probst. Following interrogation, they were all charged with treason. (73)

Sophie, Hans and Christoph were not allowed to select a defence lawyer. Inge Scholl claimed that the lawyer assigned by the authorities "was little more than a helpless puppet". Sophie told him: "If my brother is sentenced to die, you musn't let them give me a lighter sentence, for I am exactly as guilty as he." (74)

Sophie was interrogated all night long. She told her cell-mate, Else Gebel, that she denied her "complicity for a long time". But when she was told that the Gestapo had found evidence in her brother's room that proved she was guilty of drafting the leaflet. "Then the two of you knew that all was lost... We will take the blame for everything, so that no other person is put in danger." Sophie made a confession about her own activities but refused to give information about the rest of the group. (75)

Friends of Hans and Sophie had immediately telephoned Robert Scholl with news of the arrests. Robert and Magdalena went to Gestapo headquarters but they were told they were not allowed to visit them in prison over the weekend. They were not told that there trial was to begin on the Monday morning. However, another friend, Otl Aicher, telephoned them with the news. (76) They were met by Jugen Wittenstein at the railway station: "We have very little time. The People's Court is in session, and the hearing is already under way. We must prepare ourselves for the worst." (77)

Sophie's parents tried to attend the trial and Magdalene told a guard: "I’m the mother of two of the accused." He responded: "You should have brought them up better." (78) Robert Scholl was forced his way past the guards at the door and managed to get to his children's defence attorney. "Go to the president of the court and tell him that the father is here and he wants to defend his children!" He spoke to Judge Roland Freisler who responded by ordering the Scholl family from the court. The guards dragged them out but at the door Robert was able to shout: "There is a higher justice! They will go down in history!" (79)

Later that day Sophie Scholl, Hans Scholl and Christoph Probst were all found guilty. Judge Freisler told the court: "The accused have by means of leaflets in a time of war called for the sabotage of the war effort and armaments and for the overthrow of the National Socialist way of life of our people, have propagated defeatist ideas, and have most vulgarly defamed the Führer, thereby giving aid to the enemy of the Reich and weakening the armed security of the nation. On this account they are to be punished by death. Their honour and rights as citizens are forfeited for all time." (80)

Werner Scholl was in court in his German Army uniform. He managed to get to his brother and sister. "He shook hands with them, tears filling his eyes. Hans was able to reach out and touch him, saying quickly, Stay strong, no compromises." (81)

Robert and Magdalena managed to see their children before they were executed. Their daughter, Inge Scholl, later explained what happened: "First Hans was brought out. He wore a prison uniform, he walked upright and briskly, and he allowed nothing in the circumstances to becloud his spirit. His face was thin and drawn, as if after a difficult struggle, but now it beamed radiantly. He bent lovingly over the barrier and took his parents' hands... Then Hans asked them to take his greetings to all his friends. When at the end he mentioned one further name, a tear ran down his face; he bent low so that no one would see. And then he went out, without the slightest show of fear, borne along by a profound inner strength." (82)

Magdalena Scholl said to her 22 year-old daughter: "I'll never see you come through the door again." Sophie replied, "Oh mother, after all, it's only a few years' more life I'll miss." Sophie told her parents she and Hans were pleased and proud that they had betrayed no one, that they had taken all the responsibility on themselves. (83)

Else Gebel shared Sophie Scholl's cell and recorded her last words before being taken away to be executed. "How can we expect righteousness to prevail when there is hardly anyone willing to give himself up individually to a righteous cause.... It is such a splendid sunny day, and I have to go. But how many have to die on the battlefield in these days, how many young, promising lives. What does my death matter if by our acts thousands are warned and alerted. Among the student body there will certainly be a revolt." (84)

They were all beheaded by guillotine in Stadelheim Prison only a few hours after being found guilty. A prison guard later reported: "They bore themselves with marvelous bravery. The whole prison was impressed by them. That is why we risked bringing the three of them together once more-at the last moment before the execution. If our action had become known, the consequences for us would have been serious. We wanted to let them have a cigarette together before the end. It was just a few minutes that they had, but I believe that it meant a great deal to them." (85)

Primary Sources

(1) Susanne Hirzel, The New English Review (October, 2009)

I got to know Sophie Scholl when she was my group leader in the BDM. I admired her because of her eloquence and her behavior and she quickly became my very best friend. I often stayed at Sophie's parents' home and got to know her brother Hans and her sister Inge. The BDM was a scouting organization for girls. Political indoctrination was only one aspect among many others and I even became a troop leader(Scharführerin). Sophie's father Robert Scholl was a determined... pacifist and a sincere Christian. He told us about his experiences and that influenced my thinking. At that time, we jointly decided that we should do something against Hitler.

(2) Richard F. Hanser, A Noble Treason: The Story of Sophie Scholl (1979)

Her zest gradually diminished as it became more and more clear that the BDM, like all other National Socialist programs, was designed for conformity rather than liberation. The three K's that traditionally marked off the boundaries for the German female - Kinder, Kuche, Kirche (children, kitchen, and church) - would remain fully in force under the Nazis, despite the exertions of the Ideological Training Division to persuade everyone that a new day had dawned.

The shoulder-to-shoulder marching, the continual sloganeering that emphasized the group rather than the individual, came to have a suffocating effect on Sophie, who always had a sure sense of herself that she never wholly lost even when the marching, singing, and saluting were at their height. The constant pressure to give herself over to organized activity became less and less tolerable. "How can one find oneself," she once asked her diary, "if one is forever under the compulsion to pay attention to other people?"

That was hardly the attitude expected of a group leader of the BDM. It ran counter to the National Socialist insistence on unquestioning conformity in every branch and phase of German society. But Sophie Scholl's temperament was too independent to be confined for long in an ideological straitjacket. Her alienation from the League of German Girls and everything it stood for was inevitable.

(3) Sophie Scholl, letter to Fritz Hartnagel serving in the German Army (April, 1940)

There are times when I dread the war and feel like giving up hope completely. I hate thinking about it, but politics are almost all there is, and as long as they're so confused and nasty, it's cowardly to turn your back on them. You're probably smiling at this and telling yourself "She's a girl".

(4) Sophie Scholl, letter to Fritz Hartnagel serving in the German Army (28th June, 1940)

If I didn't know that I'll probably outlive many older people then I'd be overcome with horror at the spirit that's dominating history today... I'm sure you find what I'm writing very unfeminine. It's ridiculous for a girl to involve herself in politics. She should let her feminine feelings dominate her thoughts. Especially compassion. But I believe that first comes thinking, and that feelings, especially about little things that affect you directly, maybe about your own body, deflect you so that you can hardly see the big things anymore.

(5) Sophie Scholl, letter to Fritz Hartnagel serving in the German Army (September, 1940)

For me the relationship between a soldier and his people is roughly like that of a son who swears to stand by his father and his family through thick and thin. If it turns out that the father harms another family and then gets hurt as a consequence, must the son still stick by him? I can't accept it. Justice is more important than sentimental loyalty.

(6) Fritz Hartnagel, interviewed by Hermann Vinke for his book, The Short Life of Sophie Scholl (1986)

It was striking to see with what incisiveness and logic Sophie saw how things would develop, for she was warm-hearted and full of feeling, not cold and calculating. Here is an example: in winter 1941-42 there was a big propaganda campaign in Germany to get the people to give sweaters and other warm woollen clothing to the Army. German soldiers were at the gates of Leningrad and Moscow in the middle of a winter war for which they weren't prepared... Sophie said, "We're not giving anything." I had just got back from the Russian Front... I tried to describe to her how conditions were for the men, with no gloves, pullovers or warm socks. She stuck to her viewpoint relentlessly and justified it by saying, "It doesn't matter if it's German soldiers who are freezing to death or Russians, the case is equally terrible. But we must lose the war. If we contribute warm clothes, we'll be extending it."

(7) Inge Scholl, The White Rose: 1942-1943 (1983)

I still see her as she stood before me, my sister... ready to start and full of expectation. At her temple she wore a yellow daisy, retrieved from the birthday table. It was beautiful to see her dark, smooth, shiny hair hang down to her shoulders. With her large brown eyes she looked upon the world critically but with lively interest. Hers was still a child's face, with delicate features. In it there was something akin to the nervous curiosity of a young animal and at the same time an expression of great seriousness.

(8) Sophie Scholl, letter to Lisa Remppis (1941)

I think the war is starting to have powerful repercussions in every respect. Sometimes, especially of late, I've felt it grossly unfair to have to live in an age so filled with momentous events. But that's nonsense we're really being presented with scope for direct outside action.

(9) Richard F. Hanser, A Noble Treason: The Story of Sophie Scholl (1979)

They are all standing next to an openwork iron fence whose top reaches only a few inches over their heads. Peering down at them over the fence is Sophie, who is standing on something on the other side. She has evidently been there for some time. Her satchel-like briefcase, probably filled with books, is hooked by its handles to one of the fence spikes. She is wearing a knitted sweater with broad stitches, and her dark hair is falling loosely to her shoulders.

Two candid shots of Sophie caught the two sides of her character as she perched there on the iron fence in the freight yard, looking down on her brother and her friends as they waited to go off to war. In one of the photographs, her lifted arms are flung wide, and there is a correspondingly wide smile on her face. It is a light and girlish gesture at a time that could not have been happy for her. In the other picture, the mood has changed. She is holding on to the top spike of the fence rather tightly and looks down gravely, thoughtfully, at her brother and his comrades, all of them engrossed in their conversation, and none of them looking at her. Sophie's smile is gone.

(10) The fifth White Rose leaflet was entitled, Leaflet of the Resistance (February, 1943)

Germans! Do you and your children want to suffer the same fate that befell the Jews? Do you want to be judged by the same standards as your traducers? Are we do be forever the nation which is hated and rejected by all mankind? No. Dissociate yourselves from National Socialist gangsterism. Prove by your deeds that you think otherwise. A new war of liberation is about to begin. The better part of the nation will fight on our side. Cast off the cloak of indifference you have wrapped around you. Make the decision before it is too late! Do not believe the National Socialist propaganda which has driven the fear of Bolshevism into your bones. Do not believe that Germany's welfare is linked to the victory of National Socialism for good or ill. A criminal regime cannot achieve a victory. Separate yourself in time from everything connected with National Socialism. In the aftermath a terrible but just judgment will be meted out to those who stayed in hiding, who were cowardly and hesitant.

(11) The sixth White Rose leaflet was entitled, Fellow Fighters in the Resistance (February, 1943)

The day of reckoning has come - the reckoning of German youth with the most abominable tyrant our people have ever been forced to endure. We grew up in a state in which all free expression of opinion is ruthlessly suppressed. The Hitler Youth, the SA, the SS, have tried to drug us, to regiment us in the most promising years of our lives. For us there is but one slogan: fight against the party! The name of Germany is dishonoured for all time if German youth does not finally rise, take revenge, smash its tormentors. Students! The German people look to us.

(12) Roland Friesler, of the People's Court, describing the charges against Sophie Scholl (21st February, 1943)

The accused, Sophie Scholl, as early as the summer of 1942 took part in political discussions, in which she and her brother, Hans School, came to the conclusion that Germany had lost the war. She admits to having taken part in preparing and distributing the leaflets in 1943. Together, with her brother she drafted the text of the seditious Leaflets of the Resistance in Germany. In addition, she had a part in the purchasing of paper, envelopes and stencils, and together with her brother she actually prepared the duplicated copies of the leaflet. She put the prepared letters into various mailboxes, and she took part in the distribution of leaflets in Munich. She accompanied her brother to the university, was observed there in the act of scattering the leaflets.

(13) Sophie Scholl, speech in court (21st February, 1943)

Somebody, after all, had to make a start. What we wrote and said is also believed by many others. They just don't dare express themselves as we did.

(14) Thomas Mann, radio broadcast (27th June, 1943)

I say to you: Respect the peoples of Europe! Let me add, though at the moment it may sound strange to many of you who are listening, pay respect to the German people and show sympathy with them! The idea that it is impossible to distinguish between the German Volk and Nazism - that to be German and National Socialist are one and the same thing-is heard at times in the Allied countries, and put forward with some passion. But this idea is untenable and will not prevail. Too many facts testify to the contrary. Germany has set up its defenses and continues to resist, exactly as the other nations do....

Now the world is deeply moved by the events at the University of Munich, about which we have received information through the Swiss and Swedish newspapers, at first imprecisely and then with particulars that fascinate us more and more. We know now about Hans Scholl, survivor of the Battle of Stalingrad, and his sister. We know of Christoph Probst, Professor Huber, and all the others; about the Easter demonstration of students against the obscene speech of a Nazi bigwig in the auditorium maximum; we know of their martyrdom on the block; about the leaflet which they had distributed and which contains words that go far to make up for many of the sins against the spirit of German freedom committed in these unhappy years at the German universities. Indeed, this susceptibility of German youth-the youth in particular-to the National Socialist revolution of lies was painful. Now their eyes are opened, and they put their young heads on the block for their insight and for the honor of Germany. They go to their death after telling the president of the court to his face, "Soon you will be standing here, where I now stand," after bearing witness in the face of death that a new faith in freedom and honor is dawning.

Good, splendid young people ! You shall not have died in vain; you shall not be forgotten. The Nazis have raised monuments to indecent rowdies and common killers in Germany - but the German revolution, the real revolution, will tear them down and in their place will memorialize these people, who, at the time when Germany and Europe were still enveloped in the dark of night, knew and publicly declared: "A new faith in freedom and honor is dawning."

(15) Else Gebel, letter to Sophie Scholl, that was sent to her parents in November, 1946.

I have before me your picture, Sophie, earnest, questioning, standing alongside your brother and Christoph Probst. It is as if you suspected what a heavy destiny you were to fulfill, which was to unite the three of you in death.

February 1943. As a political prisoner, I am put to work in the receiving office at the Gestapo headquarters in Munich. It is my job to register those other unfortunates who have, fallen into the hands of the secret police and to record their personal data in the card catalogue which grows larger day by day.

For days now there has been feverish excitement among the officials. With increasing frequency at night the streets and houses are being painted with signs, "Down With Hitler!" "Long Live Freedom," or simply "Freedom."

At the University leaflets have been found strewn about the corridors and on the stairs. At the prison office there is a marked tenseness in the atmosphere. None of the investigative personnel come from the headquarters to the prison; most of them have been detailed on "Special Investigative Duty." Which of the brave fighters for freedom will they snare now? We who are familiar with the methods of these merciless brutes are torn with anxiety for the people who are daily apprehended....

Soon my hope that you might have been released after all is dashed. I learn that the two of you were under interrogation all night long, and toward morning you confessed; that the weight of evidence in their hands had brought you to this, after you denied everything for hours. Totally depressed, I go about my melancholy duties. I am fearful about the state of your spirit when you come down, and I hardly believe my eyes when, toward eight o'clock, you stand there absolutely calm, though tired. There, in the receiving room, I give you breakfast, and you tell me that they even gave you real coffee during the questioning. Then you are taken back to the cell, and I go along under the pretext that I have forgotten something. Before they have time to fetch me back, I have found out a number of things. You kept denying your complicity for a long time, but after all, at the university they found the text of a leaflet in Hans' pocket. Of course he had torn it up immediately and stated that it had come from a student whose name he didn't know. But the Gestapo agents had already made a thorough search of your rooms. They carefully pieced together the torn paper and found the handwriting to be the same as that of a friend of yours. Then the two of you knew that all was lost, and from that moment on all your thoughts were: We will take the blame for everything, so that no other person is put in danger. They let you alone for a few hours, and you sleep well and deeply. I begin to be amazed at you. These many hours of interrogation have no effect on your calm, relaxed manner. Your unshakable deep faith gives you the strength to sacrifice yourself for the sake of others.

Friday evening. The whole afternoon you had to submit to many questions and frame your answers, but you are not in the least fatigued. You tell me about the impending invasion, which must occur in eight weeks at the latest. Then Germany will receive blow upon blow, and at last we will be released from tyranny. Of course I am ready to believe you, but I am troubled by the fear that you will no longer be with us. You doubt that you will live to see that day, but when I tell you how long they have held my brother without bringing him to trial-more than a year now-you begin to have hope. In your case it will certainly take a long time. Gain time and you gain everything.

Today you tell me how often you scattered leaflets at the university, and in the face of the gravity of the situation, we laugh when you tell how once on the way home from a "scattering tour" you went up to a charwoman who wanted to gather up the leaflets from the steps and said to her. "Why do you pick up those sheets? Just let them lie there; the students are supposed to read them." Then again: how well you knew at all times that if ever the agents of the Gestapo caught one of you, it would cost your life. I can understand that often you were in exultant high spirits when you had completed a night's work, hanging banners in the streets or placing a stack of letters of the "White Rose" in mailboxes to await their delivery. If you happened to have a bottle of wine, you opened it in celebration of one of your successes.

You also describe for me your last action together. You and Hans have scattered the greater part of the leaflets in the university hall and are standing with your suitcase out in the Ludwigstrasse again when you decide that it ought to be possible to empty the bag before you go home. On the spur of the moment you turn around, go back into the hall and up to the top of the stairs, and fling the remaining sheets down the light well. Naturally this causes a commotion, and the Gestapo officers order all the doors locked.

Student Activities

The Political Development of Sophie Scholl (Answer Commentary)

The White Rose Anti-Nazi Group (Answer Commentary)

Kristallnacht (Answer Commentary)

Adolf Hitler's Early Life (Answer Commentary)

Heinrich Himmler and the SS (Answer Commentary)

Trade Unions in Nazi Germany (Answer Commentary)

Adolf Hitler v John Heartfield (Answer Commentary)

Hitler's Volkswagen (The People's Car) (Answer Commentary)

Women in Nazi Germany (Answer Commentary)

German League of Girls (Answer Commentary)