Joachim Fest

Joachim Clemens Fest, the son of Johannes Fest, a conservative Roman Catholic, was born in Karlshorst, near Berlin, on 8th December 1926. His father, the head teacher of the Twentieth Elementary School, was a strong opponent of Adolf Hitler and was outspoken critic of the Nazi Party. (1) In the 1920s he was a member of the Reichsbanner, a cross-party pressure group opposed to fascism. (2)

Neal Ascherson, has pointed out: "He (Johannes Fest) dominated his family, an imperious patriarch given to terrific rages at the dining-table but unbending in his attachment to straightness, good behaviour and democracy. His four principles were militant republicanism (he had detested the kaiser), Prussian virtue (taken with a spice of irony), the Catholic faith and German high culture as inherited by the educated middle class." (3)

Soon after Hitler took power Fest "was twice summoned to the local education authority, and later to the ministry, and questioned on his attitude towards the Government." On his return from the third meeting he told his wife, Elisabeth Straeter Fest, that he refused to back down and described the new government as a "rabble". She replied: "You know that I have always supported you in what you believe to be right. I always will. But have you thought of the children and what your obstinacy could mean for them?" On 20th April, 1933, was suspended from his post. (4)

Rachel Seiffert has claimed: "From 1933 until the end of the war, this intelligent and energetic man was reduced to an observer, watching the gradual erosion of civil society around him, first with incredulity and then with horror. He concentrated his efforts on his immediate circle, urging Jewish friends to leave." (5)

The Politics of Johannes Fest

Johannes Fest had been a supporter of the Social Democratic Party (SDP) before it was banned by Hitler and was friends with several politicians including Max Fechner, a SDP activist, Franz Künstler, chairman of the Berlin SDP, Arthur Neidhardt, a senior officer of the Reichsbanner, and Heinrich Krone, a former member of the Catholic Centre Party (BVP). However, he was a strong opponent of Ernst Thalmann, the leader of the German Communist Party (KPD).

Another friend was Dr. Goldschmidt, a Jewish lawyer. After the passing of the Nuremberg Laws Johannes Fest urged him to leave Germany: "But, Dr. Goldschmidt, who, as a German patriot, had always felt it his duty to drink only German red wine instead of the far superior French and to buy only German clothes, shoes, and groceries, had paid no heed. Germany, said Dr. Goldschmidt, was a state of law; it was in people's bones, so to speak." He later died in an extermination camp. (6)

In 1935 Joachim recalled hearing a row in which his mother pleaded with his father to become a member of the Nazi Party, arguing that a little hypocrisy was justified to ease the hardship the family was undergoing. "Everyone else might join, but not me... We are not little people in such matters." He used to quote the Latin maxim: "Even if others do - I do not!" Joachim later recalled seeing him come home covered in blood after fighting street battles with the Sturmabteilung (SA). (7)

The family could no longer afford servants and they all had to leave. The main loss was the nursemaid, Franziska, who according to Joachim was "after our mother, she was the dearest person to us". The children also had to make sacrifices: "There were no toys anymore and Wolfgang did not get his remote-controlled Mercedes Silver Arrow model racing car or I the football... The model railway already lacked gates, bridges, and points, so to make any progress at all we built hills out of papier-mache on which we placed home-made houses, churches, and towers." (8)

There were several visits from the Gestapo. "The men in belted leather coats who came from time to time and with a Heil Hitler! entered the apartment without waiting to be invited were more than enough to create a threatening atmosphere. Without another word they shut themselves in the study with my father, while my mother stood in front of the coat recess, her face rigid." (9)

In 1936 Joachim Fest became old enough to join the Hitler Youth. However, his father refused to allow him to join the organisation. Despite this, Fest never joined any resistance group and did nothing active to damage the Nazi dictatorship, but refused to abandon his Jewish friends until they were sent to concentration camps. (10)

In February, 1938, Adolf Hitler invited Kurt von Schuschnigg, the Austrian Chancellor, to meet him at the Berghof. Hitler demanded concessions for the Austrian Nazi Party. Schuschnigg refused and after resigning was replaced by Arthur Seyss-Inquart, the leader of the Austrian Nazi Party. On 13th March, Seyss-Inquart invited the German Army to occupy Austria and proclaimed union with Germany. (11)

In his autobiography, Not I: Memoirs of a German Childhood (2006), Joachim Fest, pointed out that his father had mixed feelings about the Anschluss: "In March 1938... German troops crossed the border into Austria under billowing flags and crowds lined the streets cheering and throwing flowers. Sitting by the wireless we heard the shouted Heil!s, the songs and the rattle of the tanks, while the commentator talked about the craning necks of the jubilant women, some of whom even fainted. It was yet another blow for the opponents of the regime, although my father, like Catholics in general, and the overwhelming majority of Germans and Austrians, thought in terms of a greater Germany, that is, of Germany and Austria as one nation. For a long time he sat with the family in front of the big Saba radio, lost in thought, while in the background a Beethoven symphony played. Why does Hitler succeed in almost everything? he pondered. Yet a feeling of satisfaction predominated, although once again he was indignant at the former victorious powers." (12)

Kristallnacht (Crystal Night)

Ernst vom Rath was murdered by Herschel Grynszpan, a young Jewish refugee in Paris on 9th November, 1938. At a meeting of Nazi Party leaders that evening, Joseph Goebbels suggested that night there should be "spontaneous" anti-Jewish riots. (13) Reinhard Heydrich sent urgent guidelines to all police headquarters suggesting how they could start these disturbances. He ordered the destruction of all Jewish places of worship in Germany. Heydrich also gave instructions that the police should not interfere with demonstrations and surrounding buildings must not be damaged when burning synagogues. (14)

Joseph Goebbels wrote an article for the Völkischer Beobachter where he claimed that Kristallnacht (Crystal Night) was a spontaneous outbreak of feeling: "The outbreak of fury by the people on the night of November 9-10 shows the patience of the German people has now been exhausted. It was neither organized nor prepared but it broke out spontaneously." (15) However, Erich Dressler, who had taken part in the riots, was disappointed by the lack of passion displayed that night: "One thing seriously perturbed me. All these measures had to be ordered from above. There was no sign of healthy indignation or rage amongst the average Germans. It is undoubtedly a commendable German virtue to keep one's feelings under control and not just to hit out as one pleases; but where the guilt of the Jews for this cowardly murder was obvious and proved, the people might well have shown a little more spirit." (16)

Johannes Fest visited Berlin the following morning: "On November 9, 1938, the rulers of Germany organized what came to be known as Kristallnacht, and showed the world, as my father put it, after all the masquerades, their true face. The next morning he went to the city center and afterward told us about the devastation: burnt-out synagogues and smashed shop windows, the broken glass everywhere on the pavements, the paper blown in the wind, and the scraps of cloth and other rubbish in the streets. After that he called a number of friends and advised them to get out as soon as possible." (17)

Joachim Fest later pointed out that Kristallnacht had an impact on Jewish children at his school: "It was at this time that, without notice, the only Jewish pupil in our class stopped coming. He was quiet, almost introverted, and usually stood a little aside from the rest, but I sometimes asked myself whether he always appeared so unfriendly because he feared being rejected by his schoolmates. We were still puzzling over his departure, which had occurred without a word of farewell... As a Jew he would soon not be allowed to go to school anyway. Now his family had the chance to emigrate to England. They didn't want to miss the chance." (18)

Johannes Fest constantly felt guilty about the crimes committed in Nazi Germany. His son rejected this idea: "Unlike the overwhelming majority of Germans, we were not part of some mass conversion… we were excluded from this psychodrama. We had the dubious advantage of remaining exactly who we had always been, and so of once again being the odd ones out." (19)

In early 1939, Dr. Hartnack, the founder and director of a language school in Berlin, offered Johannes Fest a job. He had to apply to the education department for permission to take the post. After three weeks the authorities rejected his request because of his previous refusal to join the Nazi Party. He was told that as soon as there was evidence that the "petitioner had come around to a positive assessment of the National Socialist order and of its leader Adolf Hitler, then it would be prepared to review the matter." (20)

Joachim Fest and the Second World War

Joachim Fest attended Leibniz Gymnasium. In January 1941 he had used his pocketknife to carve out a caricature of Hitler on a school desk. One of the boys who was a keen member of the Hitler Youth told his teacher about what he had done. "I denied any kind of political motive, but admitted the damage to property and asked to be shown leniency." This was rejected and he was expelled from the school. Johannes Fest was told: "It would be best if you took your other two sons (Winfried and Wolfgang) away at the same time!" (21)

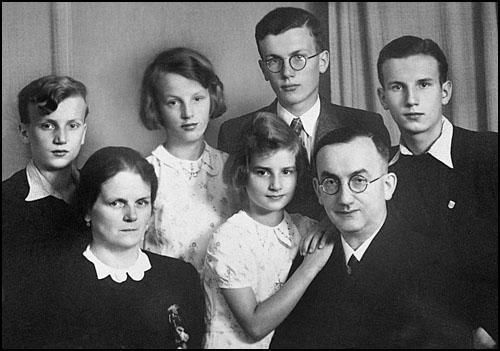

Front row: Elisabeth, Christa and Johannes Fest

In February 1941, Nazi Party officials arrived at the house and pointed out that none of his three sons had joined either the junior Jungvolk or the Hitler Youth. Johannes Fest sent them away: "Whoever you are. I have no intention of allowing you to come here, on a Sunday at that... Because we have several times been pestered, likewise on a Sunday morning, by your lads. So you haven't just found out something. And now, will you leave my house? Get out! This minute!" His wife told him: "This time you've gone too far!" However, much to his surprise, they did not return. (22)

Joachim, Wolfgang and Winfried Fest were sent to a boarding school in Freiburg. Their new head teacher, Dr. Hermann insisted that they all joined the Hitler Youth. Joachim later admitted that he quite enjoyed the experience: "The bells rang out from Bernward's tower... and we listened reverently to the beating of a drum, a so-called Landsknechtstrommel which punctured not only the addresses given and the songs, but also the heroic passages of the war stories that were read out - we had to march around in a circle in the school playground in wind and rain, crawl on our stomachs, or hop over the terrain in a squatting position holding a spade or a branch in our out-stretched hand." He also was sent away to camp where he spent time on "mindless... military training drill." (23)

Joachim Fest received a bad report at the end of his time at the boarding school. "Joachim Fest shows no intellectual interest and only turns his attention to subjects he finds easy. He does not like to work hard. His religious attachment leaves something to be desired. He is hard to deal with. He shows a precocious liking for naked women, which he hides behind a taste for Italian painting. He displays a noticeable devotion to cheap popular literature; in the course of an inspection of his work desk shortly before he left, works by Beumelburg and Wiechert were found... He is taciturn. All attempts by the rectorate to draw him into discussion were in vain. It is not impossible that Joachim will still find the right path." (24)

In July 1944, Joachim Fest volunteered to join the German Army. His father objected to him joining "Hitler's criminal war". He replied that he did this to avoid being conscripted into the Waffen SS . (25) In October he was transferred to a small town on the Lower Rhine: "There we were trained in duties as sappers, in building pontoons and in moving bridges." Soon afterwards he discovered this his brother Wolfgang had died while serving in Silesia. (26)

On 8th March, 1945, Fest was sent to Unkel in an attempt to stop the advancing American Ninth Tank Division. "At the edge of the woods we got the order to dig two-man foxholes at intervals of ten yards. Now we were told that the American Ninth Tank Division had captured the undamaged Ludendorff Bridge only hours before and an armoured advance guard had already crossed. Several attempts by the Germans to blow up the bridge or to smash the American units had failed." (27)

Historian of Nazi Germany

Fest was captured soon afterwards and was taken to a prison camp in Attichy, France. After the war Fest studied history, sociology, German literature, art history and law at Freiburg University, Frankfurt am Main University and Berlin University. He also became active in the conservative Christian Democratic Union. His first job was in radio, as in 1954 he became head of contemporary history with the American owned RIAS Berlin. (28)

Joachim Fest married Ingrid Ascher in 1959. Over the next couple of years she gave birth to two sons. In 1961 he moved to television as editor-in-chief of the German Norddeutscher Rundfunk. (29) Neal Ascherson has argued: " Fest was a handsome, restless, rather unhappy man. In postwar West Germany, he never fitted into any of the conventional slots. He had no time at all for Soviet socialism, which he considered an early variant of the virus that later produced the Nazis, or for any Western form of Marxism. But although a right-winger, he neither dreamed of reversing the outcome of the Second World War nor chose to imagine the Germans as helpless victims of a single madman: Hitler did not have to happen. No iron law of economics or sociology wheeled him into history. Human beings – German human beings – could have stopped him, but didn’t." (30)

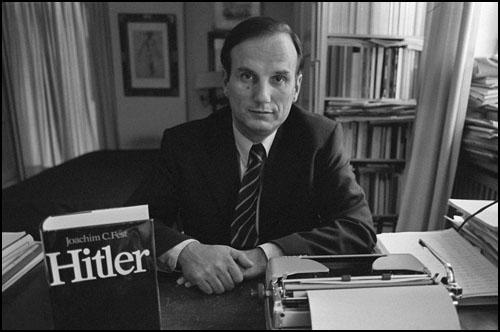

Joachim Fest's book, The Face of the Third Reich was published in 1963. Jane Burgermeister has pointed out that "his profiles of prominent Nazis... a groundbreaking work for that time, could have come straight from the pages of Dostoevsky as Fest probes in scintillating style the dysfunctional psyches, personal ambitions, contradictions and self-serving delusions of the men who helped create the Third Reich, while showing how they embodied the attitudes of their classes." (31)

The book immediately established his reputation as a historian. In 1966 he was approached by the publisher Wolf Jobst Siedler to assist Albert Speer, then approaching the end of his 20-year sentence at Spandau, in the writing of his memoirs. The result was Inside the Third Reich, Speer's memoirs, which caused a sensation when it appeared in 1969. This was followed by Speer's Spandau: The Secret Diaries. In 1973 Fest published Hitler. It has been claimed that his biography of Adolf Hitler replaced the one produced by Alan Bullock (Hitler: A Study in Tyranny) as the standard work on the subject. (32)

Fest became co-editor of the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung and the head of its culture section. In this post he argued tenaciously against the "singularity" of the Holocaust. (33) In June 1986 he created great controversy by publishing an article, The Past That Will Not Pass: A Speech That Could Be Written but Not Delivered, by fellow historian, Ernst Nolte. He argued that it was necessary in his opinion to draw a "line under the German past". Nolte complained that excessive present-day interest in the Nazi period had the effect of drawing "attention away from the pressing questions of the present - for example, the question of unborn life or the presence of genocide yesterday in Vietnam and today in Afghanistan".

Nolte then went on to discuss the Holocaust where he argued that it was not an exceptional event and could justly be compared to the crimes committed by Joseph Stalin: "It is probable that many of these reports were exaggerated. It is certain that the White Terror also committed terrible deeds... Wasn’t the Gulag Archipelago more original than Auschwitz? Was the Bolshevik murder of an entire class not the logical and factual prius of the racial murder of National Socialism? Cannot Hitler's most secret deeds be explained by the fact that he had not forgotten the rat cage? Did Auschwitz in its root causes not originate in a past that would not pass?" (34)

Joachim Fest was attacked for comparing the crimes of Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union. He rejected this and claimed that the reason for this was the "left-wing mood" of the time. He was especially critical of Günter Grass, the leading socialist writer of the time, who had attempted to deal meaningfully and critically with the Nazi experience: "When Günter Grass or any of the other countless self-accusers pointed to their own feelings of shame, they were not referring to any guilt on their own part - they felt themselves to be beyond reproach - but to the many reasons which everyone else had to be ashamed. However, the mass of the population, so they said, was not prepared to acknowledge their shame." (35) Fest's book, Plotting Hitler's Death (1997) concentrated on the right-wing resistance to Hitler.

Joachim Fest came under attack from Gitta Sereny who accused him of protecting the reputation of Albert Speer when helping him write Inside the Third Reich. Sereny claimed in her book, Albert Speer: His Battle With Truth that Speer had lied about his knowledge of the Final Solution. Fest responded by produced his own biography Speer: The Final Verdict in 1999.

The book immediately established his reputation as a historian. In 1966 he was approached by the publisher Wolf Jobst Siedler to assist Albert Speer, then approaching the end of his 20-year sentence at Spandau, in the writing of his memoirs. The result was Inside the Third Reich, Speer's memoirs, which caused a sensation when it appeared in 1969. This was followed by Speer's Spandau: The Secret Diaries. In 1973 Fest published Hitler. It has been claimed that his biography of Adolf Hitler replaced the one produced by Alan Bullock (Hitler: A Study in Tyranny) as the standard work on the subject. (36)

In 2006 Joachim Fest published his autobiography, Not I: Memoirs of a German Childhood. The title was taken from his father's maxim, taken from the Matthew's gospel: "Others betray you, not I." The book concentrates of his family's reaction to living in Nazi Germany. "The family milieu is fascinating, and will be unfamiliar to most British readers. Fest's parents were devout Catholics, proudly Prussian, and had been ardent supporters of the Weimar Republic. Regarding both communists and Nazis with deep distrust, they kept company with like-minded political activists and intellectual Catholic clergy, and had many close Jewish friends... They lived with poverty, social exclusion, and under constant threat of visits from the Gestapo, but Fest doesn't take the moral high ground. If ever a book demonstrated the slow but seemingly unstoppable reach of tyranny, even into the private realm, it is this one. He shows how tempting compromise becomes, even while it remains loathsome, and bears witness to the cost and limits of individual courage." (37)

Joachim Fest died on 11th September, 2006.

Primary Sources

(1) Joachim Fest, Not I: Memoirs of a German Childhood (2006)

In March 1938... German troops crossed the border into Austria under billowing flags and crowds lined the streets cheering and throwing flowers. Sitting by the wireless we heard the shouted Heil!s, the songs and the rattle of the tanks, while the commentator talked about the craning necks of the jubilant women, some of whom even fainted.It was yet another blow for the opponents of the regime, although my father, like Catholics in general, and the overwhelming majority of Germans and Austrians, thought in terms of a greater Germany, that is, of Germany and Austria as one nation. For a long time he sat with the family in front of the big Saba radio, lost in thought, while in the background a Beethoven symphony played. "Why does Hitler succeed in almost everything?" he pondered. Yet a feeling of satisfaction predominated, although once again he was indignant at the former victorious powers. When the Weimar Republic was obviously fighting for its survival, they had forbidden a mere customs union with Austria and threatened war. But when faced with Hitler, the French forgot their "revenge obsession," and the British bowed so low before him that one could only hope it was another example of their "familiar deviousness." The Weimar Republic, at any rate, would probably have survived if it had been granted a success like that of the Anschluss.

Nevertheless, my father continued, the union brought with it a hope that Germany would now become "more Catholic." It was only a few days before he realized his error. Already at the meeting with his friends, which had been brought forward, he learned of the persecution of the Jews in Austria, heard dumbfounded that he admired Egon Friedell, whose Cultural History of the Modern Age was one of his favorite books, had jumped out of the window as he was about to be arrested, and that in what was now called the Ostmark there was an unprecedented rush to join the SS. "Why do these easy victories of Hitler's never stop?" he asked one evening, after a pensive listing of events. And why, he asked on another occasion, was this mixture of arrogance and hankering for advantage breaking out in Germany, of all places? Why did the Nazi swindle not simply collapse in the face of the laughter of the educated? Or of the ordinary people, who usually have more "character"?

So there were ever more occasions for that conspiratorial feeling that bound us together; at least that's how my father interpreted the course of events. During the summer several members of my father's "secret society," as Wolfgang and I ironically called it, visited us: Riesebrodt, Classe, and Fechner. Hans Hausdorf also came regularly again, and brought us children "presents to suck" and, as always, a pastry for my mother. His center-parted hair was combed down flat and gleamed with pomade. We loved his puns and bad jokes. And, indeed, Hausdorf seemed to take nothing seriously. But once, later on, when we took him to task, his mood turned unexpectedly thoughtful. He said that human coexistence really only began with jokes; and the fact that the Nazis were unable to bear irony had made clear to him from the start that the world of bourgeois civility was in trouble.

(2) Joachim Fest, Not I: Memoirs of a German Childhood (2006)

On November 9, 1938, the rulers of Germany organized what came to be known as Kristallnacht, and showed the world, as my father put it, after all the masquerades, their true face. The next morning he went to the city center and afterward told us about the devastation: burnt-out synagogues and smashed shop windows, the broken glass everywhere on the pavements, the paper blown in the wind, and the scraps of cloth and other rubbish in the streets. After that he called a number of friends and advised them to get out as soon as possible.

(3) Joachim Fest, Not I: Memoirs of a German Childhood (2006)

It was at this time that, without notice, the only Jewish pupil in our class stopped coming. He was quiet, almost introverted, and usually stood a little aside from the rest, but I sometimes asked myself whether he always appeared so unfriendly because he feared being rejected by his schoolmates. We were still puzzling over his departure, which had occurred without a word of farewell, when one day, as if by chance, he ran into me near the Silesian Station, and took the opportunity to take his leave personally, as he said. He had already done so with a few other classmates, who had behaved "decently"; the rest he either hadn't known or they were Hitler Youth leaders, most of whom had also been friendly to him, often "very friendly indeed," but he didn't see why he should say goodbye to them. As a Jew he would soon not be allowed to go to school anyway. Now his family had the chance to emigrate to England. They didn't want to miss the chance. "Pity!" he said, as we parted, and he was already three or four steps away. "This time it is forever, unfortunately."

(4) Joachim Fest, Not I: Memoirs of a German Childhood (2006)

One Sunday at the beginning of February 1941, shortly after we had come back from church, two senior Hitler Youth officials entered the building, banging the street door and demanding to speak to my father. They had just found out-one of them shouted from the bottom of the stairs-that none of his three sons had joined either the junior Jungvolk or the Hitler Youth. There had to be an end to it. "Malingering!" barked the other. "Impertinence! How dare you!" Everybody had duties. "You, too!" the first one joined in again.My father had, meanwhile, gone down to the pair. "Whoever you are," he responded, frowning in annoyance, "I have no intention of allowing you to come here, on a Sunday at that, with a lie. Because we have several times been pestered, likewise on a Sunday morning, by your lads. So you haven't just found out something." And getting ever louder, he finally roared at them, "You accuse me of malingering and are yourself cowards!" And after a few more rebukes he shouted from the second step over their army-style cropped heads, "And now, will you leave my house? Get out! This minute!" The pair seemed speechless at the tone my father dared to use, but before they could reply he drove them back, so to speak, through the entrance lobby and out the door. The commotion had initially startled the whole building, and several tenants had appeared on the stairs. At the sight of the uniforms, however, they quietly closed the doors to their apartments.

Hardly had the street door closed behind the two Hitler Youth leaders when my father raced up the stairs to calm my mother. She was standing in the door as if paralyzed and only said, "This time you've gone too far!" My father put his arm around her and admitted he had forgotten himself for a moment. But first the Nazis had stolen his profession and his income, now they were attacking his sons and Sunday itself One had to show these people that there was a limit. "They know none," said my mother in an expressionless voice. It was all the more important, objected my father, to point it out to them.

(5) Joachim Fest, Not I: Memoirs of a German Childhood (2006)

The bells rang out from Bernward's tower... and we listened reverently to the beating of a drum, a so-called Landsknechtstrommel which punctured not only the addresses given and the songs, but also the heroic passages of the war stories that were read out - we had to march around in a circle in the school playground in wind and rain, crawl on our stomachs, or hop over the terrain in a squatting position holding a spade or a branch in our out-stretched hand...The duty at Haslach Camp was as mindless as all military training drill. We had to march up and down the wide pebble paths between the sheds, throw ourselves onto the ground at a command, do rifle drill, put on footcloths, and, time after time, perform the salutes as prescribed in army regulations "with a straight back". Furthermore, we were instructed in gunnery and ballistics, cleaning latrines, putting locker contents "in order" and fetching coffee.

(6) Neal Ascherson, London Review of Books (25th October, 2012)

To be right when everybody else has been wrong can be a lonely, even disabling experience. This may be a way of understanding the enigmatic character of Joachim Fest, the German historian, journalist and editor who died six years ago. His Berlin family belonged to the Bildungsbürgertum - roughly, the well-educated middle class - and rejected Hitler and National Socialism from the very first moment. They were not part of any resistance group; they did nothing ‘active’ to damage the Nazi dictatorship. They simply refused to let this dirty, vulgar, evil thing across the threshold until, in the final stages of the war, it broke in and took their sons and their father away to defend the collapsing Reich. For their defiance – refusing to join the Hitler Youth or League of German Maidens voluntarily, refusing to abandon their Jewish friends until they ‘disappeared’ - the father lost his job as a headmaster and was banned from all employment. The family was repeatedly threatened by the Gestapo and denounced by its neighbours. They were lucky nothing worse happened to them.Fest was six when Hitler came to power and an 18-year-old prisoner of war when the Führer committed suicide. Much later, he was to become a historian, a maverick conservative of independent mind. He wrote one of the earliest postwar biographies of Hitler in German, and another of Albert Speer. In 1986, as cultural editor of the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, he published the article by Ernst Nolte which was held to ‘relativise the Jewish Holocaust’ and touched off the Historikerstreit dispute over the uniqueness of Nazi crime.

Fest was a handsome, restless, rather unhappy man. In postwar West Germany, he never fitted into any of the conventional slots. He had no time at all for Soviet socialism, which he considered an early variant of the virus that later produced the Nazis, or for any Western form of Marxism. But although a right-winger, he neither dreamed of reversing the outcome of the Second World War nor chose to imagine the Germans as helpless victims of a single madman: Hitler did not have to happen. No iron law of economics or sociology wheeled him into history. Human beings – German human beings – could have stopped him, but didn’t.

It was the matter of postwar guilt which isolated him. His family was exceptional because it had no reason to apologize for National Socialism, although his father, especially, felt searing shame for his country. Fest clearly found the cult of guilt unconvincing. If you looked more closely, he believed, you could see that the penitent was almost always blaming other people – his neighbours, his nation collectively – and never himself. There was a silent consensus not to stare into the bathroom mirror in the search for causes. The mood was rather: "Yes, we admit that Germany under that criminal regime was guilty; now let’s move on." But Fest, because he was genuinely not guilty, couldn’t play this game. "Unlike the overwhelming majority of Germans, we were not part of some mass conversion … we were excluded from this psychodrama. We had the dubious advantage of remaining exactly who we had always been, and so of once again being the odd ones out." So, too, did quite a few survivors of the sacrificial plots against Hitler. Everyone was respectful to them (unless they had been communists) and gave them medals. But in the Bonn republic they were decorated strangers, with a space around them.

Fest was born in Berlin, into a Catholic family. His grandfather had been the manager of the new housing scheme of Karlshorst, on the eastern edge of the city, where the Fests settled. But it’s his father, Johannes Fest, headmaster of a primary school, who is in most ways the central figure of this book. He dominated his family, an imperious patriarch given to terrific rages at the dining-table but unbending in his attachment to straightness, good behaviour and democracy. His four principles were militant republicanism (he had detested the kaiser), Prussian virtue (taken with a spice of irony), the Catholic faith and German high culture as inherited by the educated middle class. He had been wounded in the First World War, and his patriotism was at once critical and old-fashioned, free of neo-pagan triumphalism and yet rooted in traditional stereotypes. When France fell in 1940, he remarked that "he was glad from the bottom of his heart at the French defeat, but could never be so at Hitler’s triumph." This kind of ambiguity - yes, but if only someone other than Hitler had achieved it - paralysed would-be conspirators responses to the Czechoslovak crisis in 1938, the destruction of Poland and even the invasion of the Soviet Union in 1941. There weren’t many like Dietrich Bonhoeffer, who could cut the knot and hope for the defeat of their own country.

(7) Rachel Seiffert, The Guardian (10th August, 2006)

Joachim Fest was the editor of Albert Speer's correspondence, as well as the author of an early biography of Adolf Hitler and the definitive account of the last days of the Third Reich. But if his subject matter was challenging, then he had a personality to match. Not only a noted historian, he was a public intellectual of rigour, unrelenting in his pursuit of the issue at hand.

During the bitter historians' dispute in the 80s about the Holocaust, referred to as the Historikerstreit, Fest argued tenaciously against the "singularity" of the Holocaust; an iconoclastic position at the time, and still controversial – and painful – to many now. Co-publisher of the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, one of Germany's most respected broadsheets, Fest was a thorn in the side of the West German leftist intellectual orthodoxy before the fall of the Wall. His great value as a journalist was that he could cut through to the nub of a question, often with a cool, if cruel, wit. Take his response to Günter Grass's Waffen SS membership, revealed 50 years after the fact. "I can't understand how someone who for decades set himself up as a moral authority, and rather a smug one, could pull this off."

So the uncompromising Not Me of the title seems entirely in keeping with Fest's character. Actually, it was his father's maxim, taken from the Matthew's gospel: "Others betray you, not I." Fest had an early grounding in intransigence, and this is what makes this memoir so intriguing. It covers not his career, but rather his passage into adulthood during the Third Reich.

The family milieu is fascinating, and will be unfamiliar to most British readers. Fest's parents were devout Catholics, proudly Prussian, and had been ardent supporters of the Weimar Republic. Regarding both communists and Nazis with deep distrust, they kept company with like-minded political activists and intellectual Catholic clergy, and had many close Jewish friends.

Great weight was given to learning in this circle, and Fest marks the stages of his formative years by the books he was given to read. At his boarding school in Freiburg, southern Germany, he buried himself in Schiller's Wallenstein "throughout the autumn and early winter of the Russian campaign, so that for me, Freiburg is forever associated with Schiller and as an absurd contrast to the ice storms and blizzards outside Moscow".

Immersed in both high culture and current events, the young Fest was also taken seriously by the adults who passed through his household. This was evidently stimulating for a quick and developing mind, and perhaps also established the intellectual certainty that so marked him out in adulthood. After Fest made clear to his headmaster how parochial he thought him, his fellow pupils asked: "Have you no manners?" "I certainly did, I retorted, but only where there was mutual respect."

The author's bone-dry humour is evident throughout the memoir. It emerges as just one of the many defences the family had to cultivate to endure the Nazi era. They lived with poverty, social exclusion, and under constant threat of visits from the Gestapo, but Fest doesn't take the moral high ground. If ever a book demonstrated the slow but seemingly unstoppable reach of tyranny, even into the private realm, it is this one. He shows how tempting compromise becomes, even while it remains loathsome, and bears witness to the cost and limits of individual courage.

His memories of his father are particularly affecting in this regard. Johannes Fest was a school teacher, whose repeated refusal to join the Nazi party led to him being banned from employment. From 1933 until the end of the war, this intelligent and energetic man was reduced to an observer, watching the gradual erosion of civil society around him, first with incredulity and then with horror. He concentrated his efforts on his immediate circle, urging Jewish friends to leave, and seeing off the Hitler Youth who came calling to forcibly recruit his sons.

Fest absorbed his father's scathing view of the regime, scratching caricatures of Hitler on to his school desk. At the meeting that confirmed his subsequent expulsion, Fest's father put his arms about him – a rare and bravely public show of approbation. His blessing was not easily won. Of Fest's chosen field, his father said the Third Reich was "no more than a gutter subject. Hitler's supporters came from the gutter and that's where they belonged. Historians like myself were giving them a historical dignity to which they were not entitled".

Fest senior learnt of the developing Holocaust through friends, and his sense of impotence must have been intolerable; it certainly left its scars. When his sons entreated him to write about his experiences after the war, he responded: "I did not want to talk about it then, and I do not want to now. It reminds me that there was absolutely nothing I could do with my knowledge." While others accepted requisitioned villas in leafy suburbs from the Allies, Fest senior refused. "For compensation, my father had only the knowledge of meeting his own rigorous principles."

Not Me is a quiet, proud, often painful, always clear-eyed memoir. That it was a bestseller in Germany is perhaps not surprising, but it surely deserves wide attention in the English-speaking world. It is illuminating of the man, of the times he lived through, and also of a rare kind of moral resolve, both sobering and inspiring.

(8) The Daily Telegraph (13th September, 2006)

Joachim Fest, who died on Monday aged 79, was the most celebrated historian and the most distinguished journalist of the post-war generation in Germany.

For some 20 years, he was one of the publishers (i.e. editors) of Germany's leading newspaper, the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, responsible for its prestigious Feuilleton or culture section.

Because he was a journalist rather than a scholar, Fest's popularity aroused the envy of professorial rivals, none of whom could match the incisive elegance of his writing. Equally important was his flair for controversy. He was determined to prevent the wrong lessons being drawn from the past by the Left-wing establishment that had dominated German intellectual life since the 1960s.

Conservative in politics and Catholic by upbringing, Fest stood out among his contemporaries for his rejection of the influence of the Marxist sociologists of the Frankfurt school on the historiography of the Third Reich. Fest saw the Nazi phenomenon not as a product of capitalism, but as a moral catastrophe, made possible by the abdication of responsibility on the part of educated Germans.

Just as he despised economic reductionism, however, Fest made it his life's work to bring the Nazis down to earth, to expose their personalities and deeds to dispassionate scrutiny.

It was his mission to break the taboo that surrounded any comparison of the Holocaust with the crimes of other totalitarian regimes. This denial of the uniquely wicked character of Nazi Germany earned Fest vitriolic hostility from some quarters, particularly during the so-called Historikerstreit ("historians' dispute") of the late 1980s, which revolved around the allegation that he and other "revisionists" were seeking to play down the gravity of the Nazi genocide.

This was a grotesquely misplaced charge, but his own attitude to the Nazis was one of cool distaste rather than hatred. He believed that the German obsession with the Nazi past had become an obstacle to the country's normal evolution, and the failure of reunification to heal the wounds.

Joachim Clemens Fest was born on December 8 1926 in Berlin. His father, Hans, was a schoolmaster. A devout Catholic, he refused to join the Nazi party or to allow his children to join the Hitler Youth. His defiance of the regime got him the sack; he was not even allowed to give private tuition.

In his memoirs, which were in the process of newspaper serialisation at the time of his death, Fest recalled a dramatic argument between his parents about the ethics of joining the Nazi party for the sake of survival. His father stubbornly refused to join, declaring: "It would change everything!" This bitter experience, which left the family almost destitute, showed young Joachim the true face of the Third Reich. In 1944 he faced such a choice himself, when he decided to volunteer for the Wehrmacht in order to avoid being conscripted into the Waffen-SS. His father, who had already lost one son, did not approve of his son volunteering for "Hitler's criminal war". Later Hans Fest told him: "You weren't in the wrong, but I was in the right!"

After spending some months in a PoW camp in France, Fest returned to Germany, then went to study at the universities of Freiburg, Frankfurt and Berlin. In 1954 he was employed by the radio station RIAS-Berlin as head of contemporary history. In 1961 he joined North German Broadcasting (NDR) as editor-in-chief.

Fest had his first literary success in 1963 with The Face of the Third Reich, one of the first general accounts of the period to appear in German. The book immediately established his reputation as a profound yet readable historian.

In 1966 he was approached by the publisher Wolf Jobst Siedler to assist Albert Speer, then approaching the end of his 20-year sentence at Spandau, in the writing of his memoirs. The result was Inside the Third Reich, Speer's memoirs, which caused a sensation when it appeared in 1969. It was rumoured that Fest had virtually ghosted the book, which was followed by Speer's Spandau Diaries, but he denied that his role had been more than that of an amanuensis.Decades later, after controversy about Speer was reignited by Gitta Sereny's 1996 book, claiming that Speer had lied about his knowledge of the Final Solution, Fest produced his own biography in 1999. Speer: The Final Verdict, largely based on the notes Fest took of his conversations with his subject, is likely to remain the definitive work.

In 1973 Hitler appeared to universal acclaim. It immediately replaced Alan Bullock's biography as the standard work and has retained its value even today, despite Sir Ian Kershaw.

Other major works included a controversial account of the July plot of 1944, which criticised the British for not taking the conspirators seriously, and Inside Hitler's Bunker: The Last Days of the Third Reich (2004). This brief but brilliant portrait of Hitler's demise served as the basis of the successful film Downfall.

Joachim Fest received many honours in Germany and elsewhere. He is survived by his wife and three children. He also had a close friendship with the journalist Gina Thomas.

(9) Jane Burgermeister, The Guardian (14th September, 2006)

The work of the German historian and editor Joachim Fest, who has died at the age of 79, was shaped till its end by Adolf Hitler's rise to power during his childhood. Most notable among the several books Fest wrote on the Nazi era, from a conservative, Catholic perspective but with considerable journalistic flair, was an authoritative biography of the dictator. Though Fest often maintained that he would have been happier studying the Italian Renaissance, he felt compelled to confront the great issues of German life that he had been launched into from the start - above all, that of individual choice under a totalitarian regime.

His combination of strong narrative and psychological insight produced bestsellers, and Inside Hitler's Bunker: The Last Days of the Third Reich, published in 2004, provided the basis, along with the writings of Hitler's secretary Traudl Junge, for the film Der Untergang (Downfall) the same year.

Only last month, Fest hit the headlines when he accused Noble prizewinner Günter Grass of double standards for criticising German society for failing to deal adequately with its Nazi past while keeping secret his own membership of the Waffen-SS. Inspired by his father Johannes's resistance to the Nazis, Fest became convinced that responsibility for the emergence of the Third Reich lay with the millions of Germans who actively supported or turned a blind eye to Hitler's regime. Examination of the question will continue with the publication of Fest's own memoirs, Ich Nicht (Not Me) - his father's statement of defiance - later this month.

The plight of the "little people" caught up in brutal events engineered by others was a central feature of Fest's upbringing. He was born in Berlin, and in 1933 his father lost his job as a schoolteacher because he refused to join the Nazi party. At the age of 9, Joachim recalled hearing a row in which his mother pleaded with his father to become a party member, arguing that a little hypocrisy was justified to ease the hardship the family was undergoing. "Everyone else might join, but not me... We are not little people in such matters," Johannes, a devout Catholic, had replied; Joachim later recalled seeing him come home covered in blood after fighting street battles with Nazi Brown Shirts.

At his father's insistence, Fest did not join the Hitler Youth, but in 1944 volunteered for the army to avoid conscription into the Waffen-SS. Johannes maintained that "one does not volunteer for Hitler's criminal war" and that conscription was preferable; after spending time as a PoW in France, Joachim revisited the subject with his father: "You weren't wrong," the older man allowed him, "But I was the one who was right."

His father's integrity became the standard Fest used to measure the psychological weakness and moral prevarications of his countrymen in a lifelong quest to explain how they could have descended into the madness of the Holocaust. His profiles of prominent Nazis in The Face of the Third Reich (1963), his first success and a groundbreaking work for that time, could have come straight from the pages of Dostoevsky as Fest probes in scintillating style the dysfunctional psyches, personal ambitions, contradictions and self-serving delusions of the men who helped create the Third Reich, while showing how they embodied the attitudes of their classes. Hitler (1973) broke new ground by focusing on a psychological exploration of the Nazi leader who, Fest said, operated like "a reptile", outside established moral norms.

Speer: the Final Verdict (1999), written after the emergence of new evidence of Albert Speer's entanglement with the Nazi murder machine, is a masterly study in the psychological mechanisms of guilt and concealment. Fest concluded that Speer, Hitler's chief architect and later armaments minister - who, like his master, saw himself as an artist above all norms - did not have the moral or religious standards needed to tell the difference between good and evil, but was absorbed with technical questions of how to accomplish his aims. Speer had given his own account, with Fest's assistance, in Inside the Third Reich (1970) and Spandau: the Secret Diaries (1976).

After the war, Fest studied history, sociology, German literature, art history and law at Freiburg, Frankfurt am Main and Berlin universities, and joined the youth arm of the conservative Christian Democratic Union. His first job was in radio, as head of contemporary history with RIAS Berlin (1954-61), after which he moved to television as editor-in-chief of the Norddeutscher Rundfunk. From 1973 to 1993, he was co-editor of the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung and the head of its culture section.

In 1986, he approved the publication of an article by the revisionist historian Ernst Nolte, who compared the Holocaust with Stalin's mass murder, triggering a bitter debate about the treatment of the Nazi period by German historians. Later, Fest distanced himself from Nolte, but continued to defend Nolte's right to put forward his views.

An outspoken individualist difficult to label, Fest accused film-maker Rainer Werner Fassbinder of being anti-Nazi only out of conformity to leftwing ideology, but he was good friends with Ulrike Meinhof, the Red Army Faction terrorist, later recalling the heated political debates he had enjoyed with her at parties. The brilliant, lively, gracious Fest was a tireless critic of contemporary German society, accusing it of failing to establish clearer values as a safeguard against the emergence of another Hitler.

(10) David Childs, The Independent (22nd September, 2006)

Joachim Clemens Fest, writer and historian: born Berlin 8 December 1926; married 1959 Ingrid Ascher (two sons); died Kronberg im Taunus, Germany 11 September 2006.

Although he wrote about many aspects of the Germany of his childhood, Nazi Germany, Joachim Fest will be best remembered for his biography of Adolf Hitler.

Controversially, he explained the rise of Hitler in the fear of the German middle classes of Bolshevism, in the shape of the large German Communist Party (KPD). But, in many respects, Fest was trying to answer the question which troubled the thinking, caring members of his generation, sometimes called the "Hitler Youth generation" - "How did we, and our parents, get into that awful, diabolical mess, the Hitler mess?"

Born in 1926 in the pleasant Berlin suburb of Karlshorst, he attended grammar school there and later, after being expelled for anti-Nazi remarks, in Freiburg im Breisgau. However, the Second World War caught up with him. The town was bombed by the Luftwaffe by mistake, and later, by the RAF. Fest was sent as a boy helper to an anti-aircraft battery. When the war ended in 1945 he was serving as a soldier in the Luftwaffe. He was lucky to be a prisoner of the US Army and got early release. His father spent years in a Soviet labour camp.

Studies in law, history, art history, German and sociology took him to Freiburg im Breisgau, Frankfurt am Main and Berlin. There, he worked for the much-admired American radio station RIAS, from 1954 to 1961, as editor in charge of contemporary history. He then served as editor-in-chief of television for North German Radio, NDR, from 1963 to 1968. He resigned from NDR after a disagreement....

Between 1973 and 1993, he edited the culture section of the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung. During his time at the newspaper, Fest became involved in the so-called "Historikerstreit" (controversy among historians) because he published an article by a fellow historian, Ernst Nolte, "Vergangenheit, die nicht vergehen will" ("The Past That Will Not Disappear") which brought criticism that it was "revisionist" in relation to Nazi Germany and the Holocaust.

Student Activities

Adolf Hitler's Early Life (Answer Commentary)

Heinrich Himmler and the SS (Answer Commentary)

Trade Unions in Nazi Germany (Answer Commentary)

Adolf Hitler v John Heartfield (Answer Commentary)

Hitler's Volkswagen (The People's Car) (Answer Commentary)

Women in Nazi Germany (Answer Commentary)

References

(1) David Childs, The Independent (22nd September, 2006)

(2) Joachim Fest, Not I: Memoirs of a German Childhood (2006) page 17

(3) Neal Ascherson, London Review of Books (25th October, 2012)

(4) Joachim Fest, Not I: Memoirs of a German Childhood (2006) page 46

(5) Rachel Seiffert, The Guardian (10th August, 2006)

(6) Joachim Fest, Not I: Memoirs of a German Childhood (2006) page 86

(7) Jane Burgermeister, The Guardian (14th September, 2006)

(8) Joachim Fest, Not I: Memoirs of a German Childhood (2006) page 52

(9) Joachim Fest, Not I: Memoirs of a German Childhood (2006) page 55

(10) Neal Ascherson, London Review of Books (25th October, 2012)

(11) Alan Bullock, Hitler: A Study in Tyranny (1962) pages 425-429

(12) Joachim Fest, Not I: Memoirs of a German Childhood (2006) page 118

(13) James Taylor and Warren Shaw, Dictionary of the Third Reich (1987) page 67

(14) Reinhard Heydrich, instructions for measures against Jews (10th November, 1938)

(15) Joseph Goebbels, article in the Völkischer Beobachter (12th November, 1938)

(16) Erich Dressler, Nine Lives Under the Nazis (2011) page 66

(17) Joachim Fest, Not I: Memoirs of a German Childhood (2006) page 123

(18) Joachim Fest, Not I: Memoirs of a German Childhood (2006) page 125

(19) Neal Ascherson, London Review of Books (25th October, 2012)

(20) Joachim Fest, Not I: Memoirs of a German Childhood (2006) page 140

(21) Joachim Fest, Not I: Memoirs of a German Childhood (2006) page 174

(22) Joachim Fest, Not I: Memoirs of a German Childhood (2006) page 177

(23) Joachim Fest, Not I: Memoirs of a German Childhood (2006) page 207

(24) School report of Joachim Fest (May, 1944)

(25) The Daily Telegraph (13th September, 2006)

(26) Joachim Fest, Not I: Memoirs of a German Childhood (2006) pages 268-271

(27) Joachim Fest, Not I: Memoirs of a German Childhood (2006) pages 285

(28) Jane Burgermeister, The Guardian (14th September, 2006)

(29) David Childs, The Independent (22nd September, 2006)

(30) Neal Ascherson, London Review of Books (25th October, 2012)

(31) Jane Burgermeister, The Guardian (14th September, 2006)

(32) The Daily Telegraph (13th September, 2006)

(33) Rachel Seiffert, The Guardian (10th August, 2006)

(34) Ernst Nolte, Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung (6th June, 1986)

(35) Joachim Fest, Not I: Memoirs of a German Childhood (2006) page 388

(36) The Daily Telegraph (13th September, 2006)

(37) Rachel Seiffert, The Guardian (10th August, 2006)